Abstract

Collagen fibers are a primary load-bearing component of connective tissues and are therefore central to tissue biomechanics and pathophysiology. Understanding collagen architecture and behavior under dynamic loading requires a quantitative imaging technique with simultaneously high spatial and temporal resolutions. Suitable techniques are thus rare and often inaccessible. In this study, we present instant polarized light microscopy (IPOL), in which a single snapshot image encodes information on fiber orientation and retardance, thus fulfilling the requirement. We utilized both simulation and experimental data from collagenous tissues of chicken tendon, sheep eye, and porcine heart to evaluate the effectiveness of IPOL as a quantitative imaging technique. We demonstrate that IPOL allows quantitative characterization of micron-scale collagen fiber architecture at full camera frame rates (156 frames/second herein).

Keywords: polarized light microscopy, collagen, biomechanics, deformation

1. Introduction

Collagen fiber organization varies through our bodies, from highly anisotropic in tendon [1], to isotropic in skin [2, 3] and parts of sclera [4, 5]. This organization strongly influences the mechanical properties and behavior of tissues and organs [2]. To fully understand organ physiology and pathology, it is essential to understand collagen fiber organization [6, 7]. One of the techniques most often deployed to visualize and characterize collagen organization and architecture is polarized light microscopy (PLM) [8-10]. PLM takes advantage of the intrinsic birefringence of collagen, and does not require tissue labels or stains. Conventional quantitative analysis of collagen organization using PLM, however, requires multiple images, typically four, under various polarization states [8, 11-13]. This slows down image acquisition and requires image registration that may decrease image quality. Hence, PLM works well when imaging tissues under static [14, 15] or quasi-static conditions [1, 16], but not when the tissues are under dynamic loading.

Several methods have been proposed to improve the speed of PLM imaging [12, 17-19]. One approach is to switch polarization states quickly [17, 18]. Another approach is to capture all four images simultaneously using pixel multiplexing on a single image sensor [12, 20]. Although excellent biomechanics information has been obtained using these techniques [21, 22], the improved imaging speed comes at the cost of spatial resolution. In addition, these techniques need post-processing to derive the information of interest, such as fiber orientation and local retardance. This makes real-time visualization more challenging, and requires previewing analysis output on a computer screen, rather than seeing objects directly through the microscope. Shribak recently introduced a variation of PLM based on a single image, which does not require post-processing to reveal variations in collagen orientation or retardance [23]. Shribak, however, only presented the technique qualitatively. Our goal in this work was to demonstrate a technique inspired by Shribak’s original work, which we termed instant polarized light microscopy (IPOL). The analysis techniques we introduce show that IPOL is suitable for the quantitative analysis of the architecture and dynamics of collagenous tissues with high spatial and temporal resolutions. The robustness of IPOL was demonstrated for sheep eyes, pig chordae tendineae, and chicken tendon.

2. Methods

This section is organized into four parts. In Section 2.1, we describe the IPOL imaging system we developed based on a commercial inverted microscope. As we will show, images acquired using IPOL encode information on fiber orientation and retardance through pixel color and intensity. In Section 2.2, we introduce a framework based on Mueller-matrix formalism to determine the relationship between color and fiber orientation over a wide range of tissue retardance values suitable for many imaging systems. This framework is evaluated and verified using simulation. With the general color-angle mapping method, in Section 2.3 we demonstrate experimentally the quantitative color-angle mapping. Specifically, we use chicken leg tendon tissues at known orientations to determine the system-specific color-angle mapping. Finally, in Section 2.4, we demonstrate IPOL applied to image and quantify collagen architecture and dynamics of ocular, vascular, and musculoskeletal collagenous tissues.

2.1. IPOL imaging system

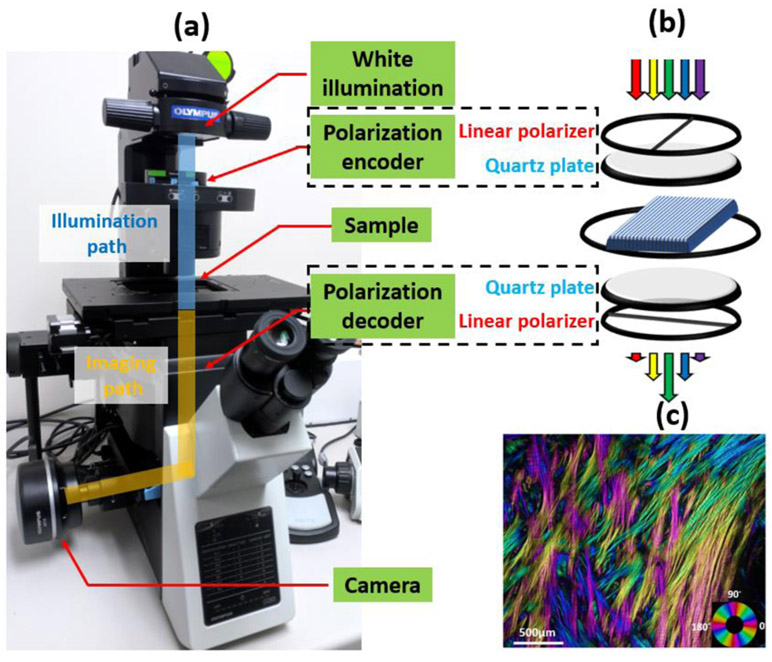

We developed an IPOL imaging system on an inverted microscope (Olympus IX 83, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) by retrofitting a polarization encoder in the illumination path and a polarization decoder in the imaging path, shown in Fig. 1a. The schematic diagram of IPOL imaging system is shown in Fig. 1b. Each polarizer group consisted of a linear polarizer and a z-cut quartz plate. Linear polarizers in the polarization encoder and decoder were orientated orthogonally. A broadband white LED light source (IX3-LJLEDC, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for illumination and strain-free objectives were used for imaging. True-color fiber orientation-encoded images were acquired by a high-speed CMOS camera (acA1920-155uc, Basler AG, Ahrensburg, Germany). In Fig. 1c, we show an example of an IPOL image of interweaving collagen fibers [5, 24] in the posterior sclera of a sheep eye. Colors in the image represent local fiber orientations, and intensity variations correlate to local retardance.

Figure 1.

(a) IPOL imaging configuration on an inverted microscope. Polarization encoder and decoder are fitted into the illumination path and imaging path, respectively. Each polarizer group consists of a linear polarizer and a z-cut quartz plate. (b) Schematic diagram of IPOL imaging system. Spectral distribution changes dependent on local fiber orientation. (c) An example IPOL image showing interweaving collagen fibers in the posterior sclera of a sheep eye. Colors represent local fiber orientation.

2.2. IPOL Simulation

A simulation framework was developed based on Mueller matrix formalism [25] to model the optical interactions between polarized light and the birefringent sample. Such interaction, based on the imaging configuration shown in Fig. 1b, can be described using Eq. 1,

| (1) |

where M is the Mueller matrix and S is the Stokes vector. To match the experimental setup, the spectrum S(λ) of an LED white light source (IX3-LJLEDC, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used in the simulation. The illumination passes through a linear polarizer M0 orientated at 0 degree and becomes linearly polarized. The polarization of the linearly polarized broadband illumination then undergoes a wavelength-dependent rotation θ(λ) introduced by a z-cut quartz before reaching the tissue. The wavelength-dependent rotation θ(λ) was previously reported at multiple wavelengths in the visible range [26]. We fitted the data and calculated θ(λ) every 1nm from 400nm to 700nm. The birefringent collagenous tissue was modeled as a phase retarder, Mtissue, with the slow axis orientation (collagen fiber orientation) ϕ varying from 0 to 90 degrees, and the retardance δ varying from 0.1 to 1.2 radians. After passing through the tissue, the light undergoes an opposite polarization-dependent rotation at the second z-cut quartz, and is then analyzed by a linear polarizer, M90, oriented at 90 degrees. For a given fiber orientation and retardance, Sout was calculated for all wavelengths between 400nm and 700 nm. This process generates an output spectrum over the same wavelength range. To generate the corresponding RGB (Red, Green, Blue) color of the spectrum, color matching functions were used first to convert the spectrum to a set of tristimulus values [27], X, Y and Z, which was further converted to R, G, and B values. The process of converting a spectrum to an RGB color is an established technique in colorimetry [27, 28] It is worth noting that rotating the illumination polarization is equivalent to rotating the sample.

To facilitate quantitative analysis, the simulated color was converted from RGB space to HSV (Hue, Saturation, Value) space [27]. The terms ‘value’ and ‘intensity’ are interchangeable. We opted to use ‘intensity’ for consistency. We established the relationships between the hue and fiber orientation, and between the intensity and retardance.

2.3. Experimental calibration: RGB color to orientation angle mapping

The simulations in section 2.2 provide valuable insight into the general imaging capabilities of IPOL. However, characteristics of the imaging system that were not incorporated in the simulations may affect the accuracy of the fiber orientations determined from the color image. Hence, we performed an experimental calibration and developed a system-specific color-angle conversion map. A thin section of chicken leg tendon was chosen due to its overall consistent fiber orientation along the longitudinal direction [8, 29]. Details of the tissue section preparation are provided below in Section 2.4.3. IPOL images were acquired with the chicken tendon section at several controlled angles relative to the longitudinal fiber direction, from 0 to 90 degrees, every 2 degrees. The individual images were then registered using FIJI software [30]. A region-of-interest (ROI) on the tissue was manually selected on the stack, and the hue of the ROI was extracted following the method described in Section 2.2. A color-angle conversion map was then computed by a circular interpolation of the measured hue and its corresponding orientation angle. The fiber orientation map for all images was then obtained by searching hue value over the color-angle conversion map for corresponding angles for all pixels.

2.4. Soft tissue imaging

To demonstrate the high spatial and temporal resolution imaging capabilities of IPOL, we used samples from three soft tissues: sheep optic nerve head, pig heart chordae tendineae, and chicken leg tendon. We chose them because all three have been used to study the general and disease-specific biomechanics of collagenous tissues [31-33]. Tendons, because of the fairly uniform collagen organization, are often used to demonstrate the accuracy of fiber orientation quantification of PLM [8]. Due to the similarity to human eyes, sheep eyes are used in ophthalmology to understand the biomechanical role of collagen fiber architecture, especially the optic nerve head region [34]. Chordae tendineae are primarily composed of collagen fibers, and play essential roles in regulating the opening and closing of heart valve leaflets [35].

2.4.1. Sheep optic nerve head

Sheep eyes from a local abattoir were prepared as described in detail previously [8]. Briefly, sheep eyes were enucleated within 4 hours after death and formalin-fixed for 24 hours at 22 mmHg of intraocular pressure. The optic nerve head region was isolated using an 11-mm-diameter trephine and cryosectioned into 16-μm-thick coronal sections. Sections were imaged with a 10x strain-free objective. To visualize regions larger than the field of view we used mosaicking [8].

2.4.2. Pig chordae tendineae

A pig heart was obtained from a local abattoir, and chordae tendineae were isolated with a razor blade. One piece of fresh chordae tendineae was mounted onto a custom uniaxial stretching device and stretched longitudinally with a strain rate of 0.4/second and simultaneously imaged with a 2x strain-free objective at 156 frames/second. During the testing, sample was kept hydrated by applying PBS solution on the sample surface. Note that the experimental testing was intended to demonstrate the potential of the technique, and does not necessarily represent the in-vivo conditions. Further, no pre-conditioning was applied.

2.4.3. Chicken leg tendon

Chicken leg tendons were used in two parts of this project: for the color-angle mapping calibration described in Section 2.3, and for demonstrating IPOL use during uniaxial mechanical testing. All samples were obtained from food-grade chicken legs purchased from a local grocery store and processed within 4 hours of acquisition. The preparation of the sample for each experiment was different.

Color-angle mapping

A chicken leg tendon was dissected and fixed with 10% formalin for 24 hours while under load to remove the natural undulations of collagen fibers, or crimp [36] . Following fixation, tendons were embedded and cryo-sectioned longitudinally into 30-μm-thick sections.

Uniaxial mechanical testing

A chicken leg tendon was dissected, and without fixing, cryo-sectioned longitudinally into 30-μm-thick sections. Sections were washed multiple times with PBS. In the uniaxial testing, a section was mounted to a custom device for mechanical testing while imaged using IPOL [37]. The stretch was applied until failure (rupture) of the section was observed. The stretching process lasted about 3 seconds and was imaged at 156 frames/second with a 4x strain-free objective.

3. Results

3.1. IPOL Simulation

Fig. 2 shows the spectrum of the illumination and the simulated spectra at three fiber orientations: 30, 60, and 90 degrees. When converting from spectrum to color, different spectral profiles generate different colors. In other words, fiber orientations are directly encoded in colors. The simulated colors of IPOL imaging are shown in Fig. 3. The RGB color map (Fig. 3a) demonstrates that the color and intensity in IPOL imaging are related to the local fiber orientation and retardance. This trend can be better appreciated by decomposing RGB color to HSV color. In the hue map (Fig. 3b), we noticed that the color was independent of the retardance, and solely determined by the fiber orientation. Hue varies monotonically with fiber orientation (Fig. 3d). The monotonic relationship ensures unique mapping between the hue and fiber orientation, which enables us to quantify the collagen fiber orientation from the color, accomplishing a primary goal of this study. Compared to the hue map, the intensity map exhibits a more complex dependency on the fiber orientation and retardance (Fig. 3c). However, we noticed that at a given fiber orientation, the normalized intensity was approximately linearly related to the retardance (Fig. 3e). In our simulation study, we did not notice a role for saturation in the quantification.

Figure 2.

Spectrum of the illumination and simulated spectra at three fiber orientations. The relative intensity of spectra depends on the fiber orientation, which thus allows for color-angle mapping.

Figure 3.

(a) Simulated IPOL RGB color maps covering fiber orientation angles from 0 to 90 degrees and retardance from 0.1 to 1.2 radians. Corresponding (b) hue and (c) intensity maps obtained by converting the simulated RGB image to HSV space. (d) Monotonic and retardance-independent color-angle relationship obtained from the simulated hue map. (e) At a set fiber orientation in the simulated intensity map, the intensity and retardance exhibit an approximately linear relationship.

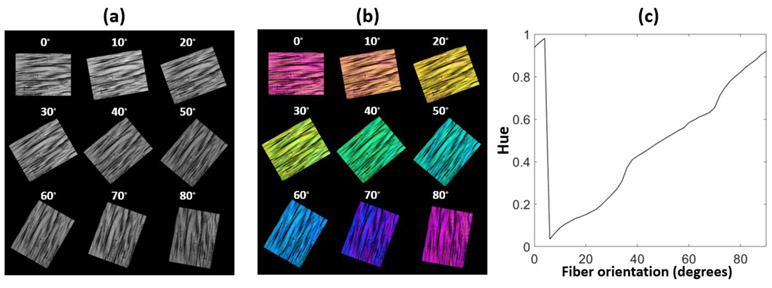

3.2. Experimental calibration: RGB color to orientation angle mapping

Images of a chicken tendon section were acquired at every 2 degrees from 0 to 90 degrees. We show a representative subset of images every 10 degrees (Fig. 4a). Images show that the color in IPOL (Fig. 4b) is dependent on the fiber orientation. Although tendon is often considered to have fairly uniform collagen organization, IPOL clearly shows regional variations in fiber content and orientation. The averaged hue of a small region of the tendon section was calculated throughout the 45 images. The hue values were then interpolated and plotted against the fiber orientation as shown in Fig. 4b. Notice the close similarity of the experimental calibration (Fig. 4c) and the one based on simulations (Fig. 3d).

Figure 4.

(a) Intensity and (b) IPOL images of chicken tendon sections. Colors correspond to fiber orientations. (c) System-specific color-angle mapping. There is a monotonic relationship between the hue and fiber orientation, as predicted by the simulations shown in Fig. 3d.

3.3. Soft tissue imaging

3.3.1. Sheep optic nerve head

Example images of a sheep optic nerve head section (Fig. 5) demonstrate the high-resolution potential of IPOL. Collagen fiber colors vary by their orientation, which significantly improves the visibility of different fiber families or bundles, and facilitates the visualization of various types of collagen architecture and interactions. The organization of the sclera into regions of circumferential, radial or isotropic fibers [38] is easily discernible by IPOL (Fig. 5a and 5b). At the center of the section is the scleral canal, with bright collagenous lamina cribrosa beams and vessel walls interspersed by neural tissues that are dark because of their low retardance. A close-up image (Fig. 5c) reveals collagen crimp (red arrow) and collagen fiber interweaving (white arrow). The sub-bundle composition of a large fiber bundle can also be observed (cyan arrow) in Fig. 5d. Note that due to the small field of view of the 10x objective, the image of the whole section was acquired using mosaicking.

Figure 5.

(a) Intensity and (b) IPOL image of a sheep optic nerve head section. Three major organizational components of the sclera are discernible. (c) Close-up of peripapillary sclera revealed highly detailed collagen fiber features: two families of crossing fiber (white arrow), collagen fiber undulations or crimp (red arrow), and sub-bundle fiber composition (cyan arrow). (d) Close-up of a bundle shows its fiber composition.

3.3.2. Pig chordae tendineae

With IPOL imaging, the pig chordae tendineae exhibited a layered architecture with a collagen core (purple color) surrounded by a cladding layer (green color) (Fig. 6a), consistent with previous reports [39]. An intensity image of the pig chordae tendineae prior to stretching is show in Fig. 6e. A total of 8.7% uniaxial stretch was applied to the chordae tendineae, and the deformation was recorded at 156 frames/second (Video S1). Figures 6a-d show four stills of the stretching with an interval of 64 ms. During the first 192ms, a strain of 7.68% was measured. The collagen core changed color from purple before stretch (Fig. 6a) to blue after stretch (Fig. 6d). Close inspection suggests collagen fiber uncrimping in the collagen core (Fig. 6f), which was confirmed by plotting the fiber orientation along the chordae. A similar uncrimping process was also observed when manually pulling a piece of sheep sclera (Video S2). As shown in Fig. 6g, collagen fiber orientation exhibits periodicity with fiber orientation alternating between 10 and 75 degrees, indicating that collagen fibers were crimped before stretch. After the stretch, however, the fiber orientation was overall flat with small variations around a mean orientation of 50 degrees, aligned with the principal axis of the chordae. Interestingly, the cladding layer maintained the same green color throughout the stretching process, which may suggest that collagen fibers in the cladding layer underwent an extension process different from the core. It is worth noting that the thickness of the pig chordae tendineae is around 300 μm. Tissue scattering and shallow-depth-field of the objective prevent us from observing and tracking individual collagen fibers. Strong banding/crimp are discernible in Fig. 6e indicative of complex 3D structure in chordae, which is fully characterized by both in-plane and out-of-plane fiber orientation. The quantified fiber orientation should be considered as the representative orientation throughout the tissue thickness, and projected onto the imaging plane (in-plane fiber orientation). In fact, based on the intensity variation, it is may also be possible to quantify the out-of-plane fiber orientation.

Figure 6.

(a-d) IPOL images of a pig chordae tendineae under longitudinal stretch captured at four time points with an interval of 64 ms; white arrows indicate the stretching direction; (e) Intensity image of the pig chordae tendineae at t=0ms. (f) close-up of the core region (red square) showing color changes indicating uncrimping; (g) fiber orientation profile along the white dashed line at t =0 ms and t = 192 ms.

3.3.3. Chicken leg tendon

Collagen fibers in the chicken tendon are predominantly aligned with the tendon main axis. In the case of the section shown in Figure 7 this direction is horizontal. The orientation coloring of IPOL shows strong and relatively uniform crimp over the entire section (Fig. 7a). Crimp is best visualized by re-coloring pixels in yellow/purple (Fig. 7e) based on the local orientation relative to its neighborhood average. The algorithm is described in detail elsewhere [40]. Upon applying a 16.7% uniaxial stretch, collagen fibers underwent uncrimping (Fig. 7b,7d and 7f) (Video S3). Figure 7i shows the deformation paths of collagen fibers in a small region (white box in Fig. 7a) obtained using digital image correlation. Collagen fibers exhibit region-dependent deformation paths. As an illustration, we show collagen fiber uncrimping over a small region-of-interest (yellow box) at 6 time points from the acquired video (Fig. 7g). High spatial and temporal resolutions of IPOL enabled the visualization of collagen fiber uncrimping with excellent details. For instance, we notice that collagen fibers in the lower part of the ROI uncrimping faster than those in the upper part. The biomechanical relevance of the uncrimping process can be understood by a force-stretch sketch (Fig. 7h) (adapted from [40]). Only minimal force is necessary to stretch a crimped fiber. As stretch increases, the fibers fully uncrimp and become “recruited”. A recruited fiber requires a linearly increasing force to stretch further. A group of fibers thus exhibits a nonlinear increase in the force needed for stretch. The rate of collagen fiber uncrimping is directly related to the fiber recruitment, which determines tissue mechanical properties and responses under load. In addition to recruitment, there is inter-fiber sliding. Deformation tracking using image processing indicates that recruitment in tendon proceeds mostly through longitudinal stretch without substantial fiber rotations (Fig. 7i).

Figure 7.

(a and b) IPOL image of a chicken tendon section before stretch and after stretch. Collagen fiber crimp can be identified by color changes along the fibers; white arrows indicate stretching direction. (c and d) Intensity images of a chicken tendon section before stretch and after stretch. (e and f) Crimp visualization before and after stretch. (g) Time-sequence images of uncrimping process from a small region of the section (yellow box). (h) Illustration of fiber recruitment under stretch (adapted from [40]). (i) Region-dependent deformation paths obtained from digital image correlation analysis shown overlaid on a greyscale image of the region (white box).

4. Discussion

We have demonstrated that IPOL is well-suited for the imaging and quantitative study of the architecture and dynamics of complex collagenous tissues. Using a combination of experiments and simulations, we have shown how to establish a quantitative color-angle mapping technique through which fiber orientation can be accurately determined with excellent spatial and temporal resolution. The quantitative characterization of local orientation is useful by itself, as shown elsewhere in this paper. It is also important because it enables further visualization and analyses of essential micro-biomechanical processes, such as load-induced collagen fiber uncrimping. The detailed real-time images of collagen tissue dynamics demonstrate that IPOL imaging overcomes limitations on speed and/or resolution encountered with other techniques traditionally used to study soft tissue architecture and mechanics, such as second harmonic generated imaging [41], small angle light scattering [42] and conventional PLM imaging [8]. Together, the high spatial and temporal resolutions of IPOL enable a deeper insight into the relationship between tissue architecture and forces, and of their roles on tissue physiology and pathology, than is usually available with conventional techniques.

We highlight three important strengths of IPOL: 1) allows direct visualization of collagen architecture in color; 2) leverages the full spatial resolution of the microscope-camera system; 3) allows imaging of tissue dynamics and biomechanics with an acquisition speed limited only by the camera. Below we expand on each of them, and on how their usefulness builds on each other to help improve understanding of tissue mechanics and dynamics.

Direct visualization in color

Collagen fibers in IPOL images are color-coded based on their local, pixel-scale, fiber orientation and retardance. In comparison to typical grayscale PLM images, this provides superior contrast, facilitating discernment of collagen fibers. Collagen fiber architecture, such as crimp and interweaving, become readily visible in color IPOL images which enables direct observation and discovery of novel tissue architecture and interactions while the tissue is being tested. Direct visualization of color at high frame rate is very convenient during general observation or when searching for “interesting tissue regions” as the orientation and retardance information are visible through the microscope ocular, even when the sample is moving and at different magnification levels. Techniques which require post-processing and calculations need time, and require users to see the results on a screen, rather than directly through the objective. This conceptually “distances” the sample from the measures.

Full spatial resolution

Conventional PLM typically requires multiple images to derive information such as fiber orientation [8, 43]. Acquiring multiple images requires time. As mentioned in the introduction, some have overcome this problem by switching polarization states quickly [17, 18]. Alternatively, it is possible to acquire the multiple images simultaneously using multiplexing on a single image sensor [12, 20]. Particularly powerful, and elegant, is the use of an analyzer grid directly built into the imaging sensor [21, 22]. However, multiple images have to be registered, which takes time and may introduce errors. Most importantly, registration usually involves interpolation, which reduces the spatial detail of the image. Multiplexing techniques, thus, involve some loss of resolution. IPOL, in contrast, preserves the highest spatial resolution offered by an imaging system by requiring only one image in order to visualize all fiber orientations, without the need for post-processing. When applied to complex biological tissues, this may reveal important architectural detail, such as sub-bundle fiber composition and crimp. For large samples, mosaicking can be used to achieve both large field-of-view and high resolution. Although mosaicking is not suitable for imaging tissue dynamics, it is still much faster than conventional PLM for imaging static samples, and preserves the camera’s native resolution. It is worth noting that tissue complexity and homogeneity/inhomogeneity may affect the resolution of IPOL. If tissues are unstretched but highly organized, like crimp, IPOL can still produce images with high spatial and angular resolution. However, if tissues are disorganized or inhomogeneous through the thickness, IPOL will only show colors of representative local fiber orientations. Consequently, both spatial and angular resolution will be limited.

Camera-limited temporal resolution

Due to the imaging speed limitations, conventional PLM can only be employed in quasi-static tissue mechanical testing. In quasi-static testing, the dynamic process is split into multiple static steps. Images are taken at each step, registered and stacked to approximate the dynamic process. This method is acceptable when the loading speed is low, or when the tissue response is slow. However, when the loading speed is high (e.g., blast and impact loading), this method would be problematic. Given adequate illumination, the imaging speed of IPOL is essentially only limited by the speed of the camera, which makes IPOL particularly well suited for imaging tissues under high-speed loading. High-speed imaging is particularly useful to study continuous yet complex tissue deformations under load, such as tissue viscoelasticity. Viscoelastic deformations at high speed are not the same as those at low speed [2]. IPOL captures complete and smooth tissue deformation trajectory in high spatiotemporal resolution, which allows us to study collagen fiber interactions at both tissue and fiber levels with unprecedented details.

We have shown a quantitative mapping of the colors in an IPOL image to collagen orientations. This mapping, however, is specific to our system. When developing future color-angle mappings for other systems, it is essential to consider the following factors: First, broad-band so-called white light sources may have substantially different spectral compositions. Second, microscope systems may introduce certain spectral attenuations through the optics, which would affect the detected colors. Finally, the tissues may vary in their absorption profile, for example due to pigments. All of the above could affect the colors observed in IPOL, and in turn the mappings. Thus, it is essential to establish a new color-angle mapping through a calibration process if the quantification condition is changed. It is worth noting that once the calibration is done, changing the acquisition settings of a microscope, such as exposure time, does not affect the quantification accuracy.

When analyzing IPOL data, it is important to consider that the orientation-encoded colors in IPOL are cyclic, i.e., repeating every 90 degrees. This helps discern even small differences in fiber orientation, allowing accurate measurement of collagen crimp, even when under high load. However, it also has some disadvantages: two fibers oriented perpendicular to each other have the same quantified orientation angles, exhibiting the same color. To adjudicate whether a 90-degree should be added to the quantified angle, the IPOL-angle could be supplemented using fiber orientations from gradient or Fourier analysis of the retardance map [44]. Such techniques are substantially less sensitive than IPOL, but are likely sufficient to discern orientation quadrant. Gradient and Fourier methods also do not provide information on tissue retardance.

A limitation of IPOL, as presented in this work, is that it is based on transmitted light microscopy. This, in turn, requires that the tissue samples are cut into fairly thin sections to be compatible with the configuration of a microscope, such as the magnification and numeric aperture, to achieve optimal imaging results. A thicker section may still be imaged with IPOL. However, the image quality may be affected by the tissue scattering and shallow depth-of-field. The chordae selected was thin enough to produce good results without sectioning. Other tissues worked better sectioned. Thicker chordae or other tissues may require sectioning if their scattering is strong or if their microarchitecture is complex. A thin section may have a substantial effect on the biomechanics of the structure under study. It is essential to carefully consider this when deciding to use IPOL or interpreting results obtained from it. IPOL shares this limitation with other techniques based on transmitted light. However, because of the use of cumulative retardance, IPOL is particularly sensitive to sample thickness. In some conditions, such as thick samples, it may be more appropriate to use techniques based on reflected light, such as structured polarized light microscopy [45], second harmonic generated imaging [41]and confocal microscopy [46], or full-thickness techniques, such as small angle light scattering [42]. Similar to other light microscopy techniques, if a sample is larger than the field-of-view of a specific microscope configuration, image mosaicking is needed to acquire the entire view of the sample. Image mosaicking in IPOL would be most appropriate for imaging samples that are still, or moving slowly, rather than imaging tissue dynamics. For briefness, in this work we demonstrated IPOL using only one sample of each tissue. In our laboratory we have obtained reliable and repeatable results for tissues from several species, including sheep, pig, rat, guinea pig, monkey and human. Nevertheless, further work is necessary to establish if the measurements are affected by differences between species or samples, for example in collagen type.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we present IPOL as a technique for imaging connective tissues with high spatial and temporal resolutions. IPOL optically encodes collagen orientation and architecture information in a single snapshot image with color and intensity, respectively, without post-processing. The real-time imaging capability of IPOL allows to quantify changes in collagen morphology and architecture under dynamic loading, which can provide valuable information for the understanding of tissue dynamics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research work was supported, in part, by grants from National Institutes of Health under Grant Nos. NIH R01-EY023966, R01-EY028662, T32-EY017271, and P30-EY008098, Eye and Ear Foundation (Pittsburgh, PA) and Research to prevent blindness (support to the UPMC Department of Ophthalmology). We thank Dr. Rouzbeh Amini for providing the cardiac tissues.

Funding: National Institutes of Health R01-EY023966, R01-EY028662, P30-EY008098 and T32-EY017271 (Bethesda, MD), the Eye and Ear Foundation (Pittsburgh, PA) and Research to Prevent Blindness (support to the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pittsburgh)

References

- 1.Yang B, Lesicko J, Sharma M, Hill M, Sacks MS, and Tunnell JW, "Polarized light spatial frequency domain imaging for non-destructive quantification of soft tissue fibrous structures," Biomedical optics express 6, 1520–1533 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fratzl P, "Collagen: structure and mechanics, an introduction," in Collagen (Springer, 2008), pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff JE, Arruda EM, and Grosh K, "Finite element modeling of human skin using an isotropic, nonlinear elastic constitutive model," Journal of biomechanics 33, 645–652 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girard MJ, Dahlmann-Noor A, Rayapureddi S, Bechara JA, Bertin BM, Jones H, Albon J, Khaw PT, and Ethier CR, "Quantitative mapping of scleral fiber orientation in normal rat eyes," Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 52, 9684–9693 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jan N-J, Lathrop K, and Sigal IA, "Collagen architecture of the posterior pole: high-resolution wide field of view visualization and analysis using polarized light microscopy," Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 58, 735–744 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boote C, Sigal IA, Grytz R, Hua Y, Nguyen TD, and Girard MJ, "Scleral structure and biomechanics," Progress in retinal and eye research, 100773 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacks MS and Yoganathan AP, "Heart valve function: a biomechanical perspective," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 362, 1369–1391 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jan N-J, Grimm JL, Tran H, Lathrop KL, Wollstein G, Bilonick RA, Ishikawa H, Kagemann L, Schuman JS, and Sigal IA, "Polarization microscopy for characterizing fiber orientation of ocular tissues," Biomedical optics express 6, 4705–4718 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goth W, Potter S, Allen AC, Zoldan J, Sacks MS, and Tunnell JW, "Non-destructive reflectance mapping of collagen fiber alignment in heart valve leaflets," Annals of biomedical engineering 47, 1250–1264 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Götzinger E, Pircher M, Sticker M, Fercher AF, and Hitzenberger CK, "Measurement and imaging of birefringent properties of the human cornea with phase-resolved, polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography," Journal of biomedical optics 9, 94–103 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shribak M and Oldenbourg R, "Techniques for fast and sensitive measurements of two-dimensional birefringence distributions," Applied Optics 42, 3009–3017 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruev V, Perkins R, and York T, "CCD polarization imaging sensor with aluminum nanowire optical filters," Optics express 18, 19087–19094 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.York T, Powell SB, Gao S, Kahan L, Charanya T, Saha D, Roberts NW, Cronin TW, Marshall J, and Achilefu S, "Bioinspired polarization imaging sensors: from circuits and optics to signal processing algorithms and biomedical applications," Proceedings of the IEEE 102, 1450–1469 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bancelin S, Nazac A, Ibrahim BH, Dokládal P, Decencière E, Teig B, Haddad H, Fernandez H, Schanne-Klein M-C, and De Martino A, "Determination of collagen fiber orientation in histological slides using Mueller microscopy and validation by second harmonic generation imaging," Optics express 22, 22561–22574 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang B, Jan NJ, Brazile B, Voorhees A, Lathrop KL, and Sigal IA, "Polarized light microscopy for 3-dimensional mapping of collagen fiber architecture in ocular tissues," Journal of biophotonics 11, e201700356 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jett SV, Hudson LT, Baumwart R, Bohnstedt BN, Mir A, Burkhart HM, Holzapfel GA, Wu Y, and Lee C-H, "Integration of polarized spatial frequency domain imaging (pSFDI) with a biaxial mechanical testing system for quantification of load-dependent collagen architecture in soft collagenous tissues," Acta biomaterialia 102, 149–168 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keikhosravi A, Liu Y, Drifka C, Woo KM, Verma A, Oldenbourg R, and Eliceiri KW, "Quantification of collagen organization in histopathology samples using liquid crystal based polarization microscopy," Biomedical optics express 8, 4243–4256 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu X, Pankow M, Huang H-YS, and Peters K, "High-speed polarization imaging of dynamic collagen fiber realignment in tendon-to-bone insertion region," Journal of biomedical optics 23, 116002 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X, Pankow M, Huang H-YS, and Peters K, "High-speed polarized light microscopy for in situ, dynamic measurement of birefringence properties," Measurement Science and Technology 29, 015203 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminsky W, Gunn E, Sours R, and Kahr B, "Simultaneous false-colour imaging of birefringence, extinction and transmittance at camera speed," Journal of microscopy 228, 153–164 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith MV, Castile RM, Brophy RH, Dewan A, Bernholt D, and Lake SP, "Mechanical properties and microstructural collagen alignment of the ulnar collateral ligament during dynamic loading," The American journal of sports medicine 47, 151–157 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.York T, Kahan L, Lake SP, and Gruev V, "Real-time high-resolution measurement of collagen alignment in dynamically loaded soft tissue," Journal of biomedical optics 19, 066011 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shribak M, "Polychromatic polarization microscope: bringing colors to a colorless world," Scientific reports 5, 17340 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang B, Hua Y, Brazile BL, Yang B, and Sigal IA, "Collagen fiber interweaving is central to sclera stiffness," Acta Biomaterialia (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collett E, "Field guide to polarization," in (Spie; Bellingham, WA, 2005), [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurlbut C Jr and Rosenfeld JL, "Monochromator utilizing the rotary power of quartz," American Mineralogist: Journal of Earth and Planetary Materials 37, 158–165 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schanda J, Colorimetry: understanding the CIE system (John Wiley & Sons, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohta N and Robertson A, Colorimetry: fundamentals and applications (John Wiley & Sons, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wren TA, Yerby SA, Beaupré GS, and Carter DR, "Mechanical properties of the human achilles tendon," Clinical biomechanics 16, 245–251 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, and Schmid B, "Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis," Nature methods 9, 676 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sigal IA, Flanagan JG, Tertinegg I, and Ethier CR, "Finite element modeling of optic nerve head biomechanics," Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 45, 4378–4387 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritchie J, Jimenez J, He Z, Sacks MS, and Yoganathan AP, "The material properties of the native porcine mitral valve chordae tendineae: an in vitro investigation," Journal of biomechanics 39, 1129–1135 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin TW, Cardenas L, and Soslowsky LJ, "Biomechanics of tendon injury and repair," Journal of biomechanics 37, 865–877 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voorhees AP, Jan N-J, Austin ME, Flanagan JG, Sivak JM, Bilonick RA, and Sigal IA, "Lamina cribrosa pore shape and size as predictors of neural tissue mechanical insult," Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 58, 5336–5346 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lam J, Ranganathan N, Wigle E, and Silver M, "Morphology of the human mitral valve: I. Chordae tendineae: a new classification," Circulation 41, 449–458 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jan N-J, Gomez C, Moed S, Voorhees AP, Schuman JS, Bilonick RA, and Sigal IA, "Microstructural crimp of the lamina cribrosa and peripapillary sclera collagen fibers," Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 58, 3378–3388 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace J, Jan N-J, Gogola A, Iasella M, Lathrop KL, Voorhees AP, Tran H, and Sigal IA, "Stretch-induced collagen bundle uncrimping and recruitment are independent of depth in equatorial sclera," Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 58, 3162–3162 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gogola A, Jan N-J, Lathrop KL, and Sigal IA, "Radial and circumferential collagen fibers are a feature of the peripapillary sclera of human, monkey, pig, cow, goat, and sheep," Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 59, 4763–4774 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millington-Sanders C, Meir A, Lawrence L, and Stolinski C, "Structure of chordae tendineae in the left ventricle of the human heart," The Journal of Anatomy 192, 573–581 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jan N-J and Sigal IA, "Collagen fiber recruitment: a microstructural basis for the nonlinear response of the posterior pole of the eye to increases in intraocular pressure," Acta biomaterialia 72, 295–305 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ram S, Danford F, Howerton S, Rodríguez JJ, and Geest JPV, "Three-dimensional segmentation of the ex-vivo anterior lamina cribrosa from second-harmonic imaging microscopy," IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 65, 1617–1629 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sacks MS, Smith DB, and Hiester ED, "A small angle light scattering device for planar connective tissue microstructural analysis," Annals of biomedical engineering 25, 678–689 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehta SB, Shribak M, and Oldenbourg R, "Polarized light imaging of birefringence and diattenuation at high resolution and high sensitivity," Journal of Optics 15, 094007 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sivaguru M, Durgam S, Ambekar R, Luedtke D, Fried G, Stewart A, and Toussaint KC, "Quantitative analysis of collagen fiber organization in injured tendons using Fourier transform-second harmonic generation imaging," Optics express 18, 24983–24993 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang B, Brazile B, Jan N-J, Hua Y, Wei J, and Sigal IA, "Structured polarized light microscopy for collagen fiber structure and orientation quantification in thick ocular tissues," Journal of biomedical optics 23, 106001 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saytashev I, Saha S, Chue-Sang J, Lopez P, Laughrey M, and Ramella-Roman JC, "Self validating Mueller matrix Micro–Mesoscope (SAMMM) for the characterization of biological media," Optics Letters 45, 2168–2171 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.