This is a 40-year perspective of the National Polyp Study (NPS), a randomized clinical trial (RCT), sponsored by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), American Gastroenterology Association (AGA), and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) with conceptualization and planning starting in 1977 and accrual beginning in 1980. We review how we approached challenges presented by the introduction of colonoscopy and polypectomy, how these findings influenced clinical practice and public health, and how the NPS model was used to address new challenges. Details of the NPS concepts, design, results, and discussion may be obtained from our previously published papers as cited in the references.1-9 The NPS was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the timing of surveillance intervals after colonoscopic polypectomy. It also addressed colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality reduction, familial risk for CRC, use of advanced adenomas as a CRC surrogate, and implications of flat and serrated lesions.

Challenge then: Can postpolypectomy surveillance intervals be lengthened?

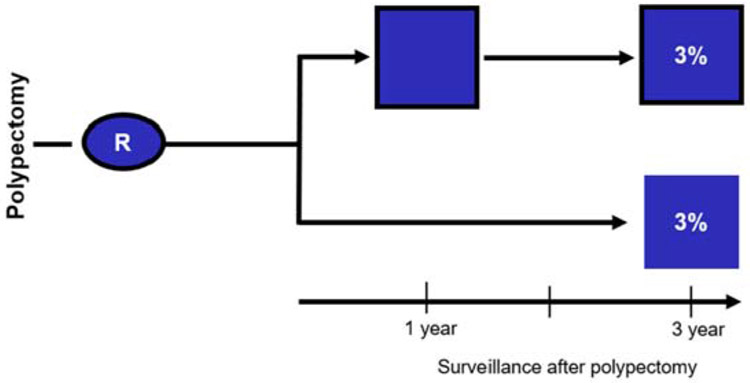

Colonoscopy had been introduced in the early 1970s, and colonoscopic polypectomy was shown to be feasible in the mid-1970s. Common practice was yearly colonoscopy after the removal of adenomas. However, observations from Lockhart-Mummery10 and Muto11 of the progressive pathology of adenomas and follow-up of a small number of patients suggested that there was a long period of time for small benign adenomas to progress into more-advanced pathology and cancer. An RCT was designed in which patients with newly diagnosed, resected, and pathology proven adenomas were assigned to have their first surveillance colonoscopy deferred to 3 years versus having a colonoscopy at 1 and 3 years.1, 7 It was difficult to enlist endoscopists in a trial in which the first postpolypectomy colonoscopy was deferred to 3 years, to convince the NCI to fund it, and to enroll patients. The 3-year interval was chosen because a 2-year interval was not substantially longer than 1 year, and more than 3 years was not acceptable to the participating endoscopy investigators. Their concern regarding missed significant pathology, especially cancer, was so high that they insisted on a fecal occult blood test each year. There had been no prior reports of a 3-year postpolypectomy surveillance interval. Before this, the NPS model of a postpolypectomy randomized trial had never before been conceptualized. Our analysis showed there was no difference in the accumulated percentage of patients with advanced adenomas in the 2 arms of the study. (RR, 1.0; 95% CI, - 0.5 to 2.2) (Figure 1). Based on the evidence in this well-designed clinical trial, it was possible to convince clinicians to accept new guidelines recommending the deferral of the first surveillance colonoscopy to 3 years.1, 2, 12

Figure 1.

Percent of patients with advanced adenomas detected with 2 surveillance colonoscopies at 1 and 3 years (3%) versus with 1 surveillance after 3 years (3%) after baseline polypectomy. (Relative risk = 1.0 with 95% confidence interval, 0.5-2.2). Advanced adenomas are defined as adenomas of size >1.0 cm or had high-grade dysplasia or invasive cancer. Current guidelines define advanced adenoma size as ≥10 mm, with tubular villous or villous component, or high-grade dysplasia.20 Data are derived from Table 6 of Winawer et al.1 From Copyright © (1993) Massachusetts Medical Society.

R represents patients randomized to 2 surveillance colonoscopies over 3 years or 1 surveillance at 3 years.

Challenges now: Can surveillance intervals be further lengthened?

The NPS observation of benefit and risk in deferring the first surveillance colonoscopy encouraged the concept of further lengthening of this interval.1, 13 The European Polyp Surveillance Study (EPoS) is investigating this concept in a current RCT. EPoS randomized patients with low-risk (ie, nonadvanced) adenomas and high-risk (ie, advanced) adenomas to shorter and longer intervals, respectively, for colonoscopy surveillance.14 The scientific environment is now more favorable to supporting larger trials with a colorectal cancer outcome measure. It has taken many years for clinicians to become comfortable with the safety of initially deferring the first surveillance colonoscopy to 3 years, and subsequently deferring low-risk patients to 5 years15 and then more recently to 5 to 10 years.16-19 Further lengthening of intervals for surveillance colonoscopies will be accepted based on well-designed clinical studies. Recent guidelines20 have reviewed additional cohort and case-control studies, which have provided evidence for lengthening such surveillance.

Challenge then: Can patients with low risk for subsequent cancer be identified for less-intense surveillance?

Lockhart-Mummery et al10 and Muto et al11 observed that risk of colorectal cancer in adenomas correlated with their pathology. Atkin21 reported that subsequent colon cancer risk was a function of the initial rectosigmoid adenoma pathology. Based on her findings in this retrospective cohort study from a pathology registry, Atkin suggested that colonoscopy surveillance may not be warranted among patients with only a single small rectosigmoid tubular adenoma. Atkin further concluded that follow-up colonoscopic examinations may be more appropriate for patients with tubulovillous, villous, or large adenomas in the rectosigmoid, especially if multiple adenomas are presented.21

The NPS prospectively demonstrated that patients with more advanced adenoma pathology at baseline had a greater CRC incidence reduction after polypectomy than those with nonadvanced pathology.2 The NPS also demonstrated that patients could be stratified to low and high risk for future advanced adenomas according to their baseline adenoma characteristics.1, 2 These findings led to subsequent 2003 guidelines15 recommendations of risk stratification with low-risk patients having their first surveillance colonoscopy examination at 5 years, whereas those with high-risk adenomas should have surveillance colonoscopy at 3 years. The 5-year surveillance for low-risk patients was based on low rates of advanced adenoma for over subsequent surveillance colonoscopies at 1, 3, and 6 years in the NPS.

Although our NPS results were based on 6 years surveillance, the guidelines elected 5-year surveillance for low-risk patients and 3 years for high risk. Five years were used as a more conservative wait time between surveillance colonoscopies, and an interval more readily adoptable by clinicians. This surveillance time was also built on an analysis showing the cumulative risk of advanced adenomas over multiple surveillances. The proportion with advanced adenomas was low in those with baseline lower risk adenomas.13

Challenge now: Can risk stratification be further delineated?

Repeated studies have validated the risk stratification and have further expanded the low-risk surveillance intervals to 5 to 10 years.16, 19 In addition, there is now an emphasis on relating continued surveillance to the findings at the first surveillance interval.20 Implementation of these concepts would reduce the burden of surveillance colonoscopy and provide more efficient use of resources for screening and diagnosis.16, 20

Challenge then: Can the adenoma-carcinoma hypothesis be tested in the NPS model?

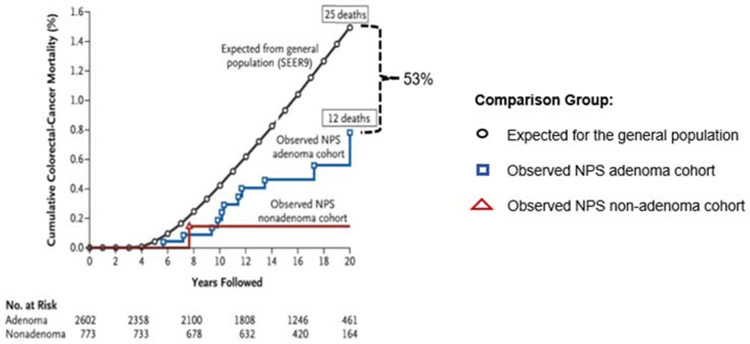

The relationship of CRC to pre-existing adenomas was first reported in 1928 from St Mark’s Hospital in London.10 Proof of the long-standing belief that CRC developed mainly from pre-existing adenomas would provide a strong basis for the clinical practice of identifying and removing adenomatous polyps. There was no feasible and ethical approach to test the adenoma-carcinoma hypothesis in an RCT in which patients with adenomas would be randomized into a group for observation only. The NPS combined patients from both arms of the surveillance study into a single postpolypectomy cohort and compared the incidence of CRC in this cohort from whom all polyps had been removed with an age and sex-matched cohort from the general population (SEER) and to 2 reference groups21, 22 from the precolonoscopy era that had polyps that had not been removed. Compared with the reference groups, there was a reduction in CRC incidence of 76% to 90% after an average follow-up of 5.9 years (Figure 2). This supported the long-standing belief in the concept of the adenoma as the precursor to CRC as well as the practice of finding and removing adenomas to prevent CRC.2

Figure 2.

Cumulative colorectal cancer incidence in the National Polyp Study cohort. The observed colorectal incidence is compared with the expected incidence on data from 3 reference groups: the Mayo Clinic cohort (United States) with rectosigmoid polyps 1 cm or larger (not removed), the St Mark’s Hospital in London with rectosigmoid polyps (removed), but no visualization or removal of polyps in the colon, and the United States general population (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) rates for 1983-1987 (from Figure 1 of Winawer2 From Copyright © (1993) Massachusetts Medical Society). 1418 patients were followed 8401 person years in the years 1980 to 1990.

Our original article2 included a sensitivity analysis on the incidence reduction by starting time at risk beginning 2 years after being enrolled in the study. This reduced the number of person-years at risk, and subsequently a smaller reduction for the effect of the polypectomy. No CRCs were detected before 3 years. These sensitivity CRC reductions were 66% (p=<0.01) to 86% (p=<0.001) rather than 76% to 90%. The 95% confidence intervals pertaining to these sensitivity analyses were still statistically significant. However, the importance of the NPS observation is not the precise number, but that removing adenomas prevents cancer, proof of a long-standing concept, which was first suggested in the 1928 St Mark’s report.10 This proof provided the rationale for colonoscopic polypectomy, with colonoscopy possibly as a screening examination, and the change of screening goals to include prevention as well as early stage CRC detection.

We excluded patients from the randomized clinical trial who had large (>3 cm) sessile polyps because the endoscopists were reluctant to possibly have those patients’ surveillance deferred for 3 years. Endoscopists were concerned about randomizing patients with these lesions to possibly a 3-year deferred follow-up. Even today, such patients with large sessile polyps are excluded from the 3- versus 5-year surveillance intervals and have shorter follow-up.

Challenges now: Will the NPS CRC incidence reduction after polypectomy be observed after screening colonoscopy?

After the NPS observations that removing adenomas reduced the expected rate of CRC, several cohort studies suggested that screening colonoscopy was effective.19, 23 There are now 2 randomized trials of screening colonoscopy compared with controls in progress to test this effect.24, 25

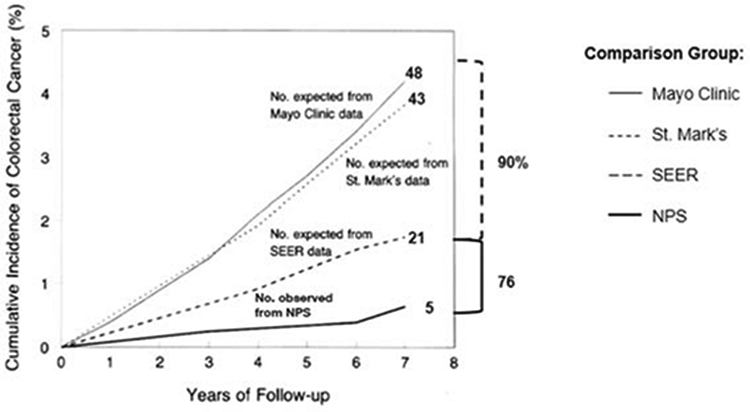

Challenge then: Does colonoscopy and removal of adenomas prevent CRC death?

The benefit of removing adenomas to prevent CRC can be challenged as overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Perhaps the cancers emerging from adenomas would never have surfaced clinically in the patients’ lifetimes, or if they had surfaced would not have been lethal. To address this issue, the long-term effect on CRC mortality in the NPS postpolypectomy cohort was initiated. All the polyps identified on initial and surveillance colonoscopy were removed regardless of size. In a follow-up of the NPS cohort with matching to the National Death Index, mortality from CRC in patients with adenomas removed was compared with the incidence-based mortality in the general population (SEER) and with patients who had nonadenomatous polyps removed. A 53% reduction in CRC mortality was seen over a median of 15.8 years in the patients who had adenomas removed compared with that expected in the general population (Figure 3).5

Figure 3.

Cumulative colorectal cancer mortality of colorectal cancer in the National Polyp Study cohort of adenoma patients compared with the incidence-based mortality of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER9) and to a cohort with no adenomas. (From Figure 1 of Zauber et al5)From Copyright © (2012) Massachusetts Medical Society).

However, how much surveillance is required for the effectiveness of colonoscopy overall, and in low- and high-risk patients is still to be determined. NPS surveillance was tracked for up to only 6 years after polypectomy. We have shown in a microsimulation modeling analysis that there is a greater impact on postpolypectomy incidence reduction from the initial polypectomy than from surveillance.26, 27

The NPS CRC mortality analysis supported the hypothesis that colonoscopic removal of adenomatous polyp prevents CRC that is potentially fatal and is therefore of clinical importance.5 This report helped increase public awareness of the benefit of screening and surveillance colonoscopy with removal of adenomas.28, 29

Challenges now: Will the NPS mortality effect be translated into a mortality effect after screening colonoscopy?

Demonstration by NPS of a mortality reduction after colonoscopic polypectomy invited the question whether screening colonoscopy with removal of adenomas would similarly reduce CRC mortality. RCTs of screening colonoscopy compared with controls or FIT will address this.24, 25, 30, 31

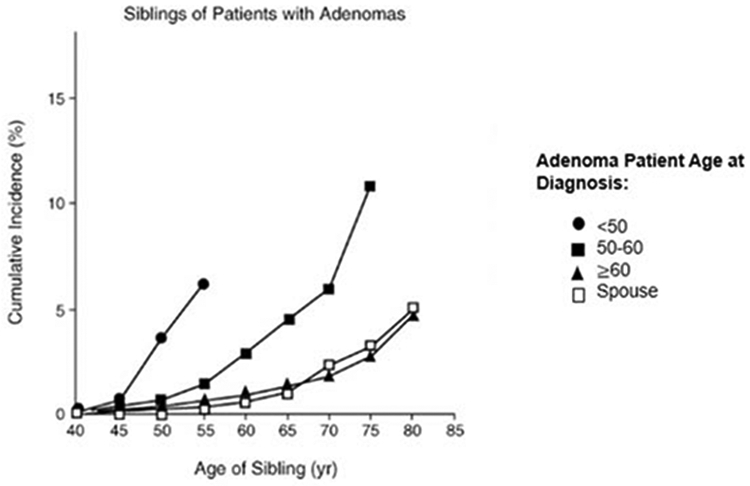

Challenge then: Is there a familial CRC risk of NPS adenoma probands?

A family history of colorectal cancer in first-degree relatives is associated with an increased risk of CRC, especially in younger people in prospective studies32 and case-control studies.33 Given that the adenoma is considered to be the precursor lesion for colorectal cancer, whether family members of adenoma patients would be associated with an increased risk of CRC warranted further exploration. We asked in NPS whether first-degree relatives of patients with adenomas would have an increased risk for CRC compared with spouse controls.

We therefore conducted a retrospective cohort study in the NPS and assessed the cumulative risk of CRC in cohorts of siblings and parents to that of a cohort of spouses. The CRC status for family members and spouses was obtained from the adenoma patients. This ensured that knowledge of the CRC status was equivalent among both family members and spouses alike. Adenoma patients who were referred for colonoscopy because of family history of CRC were excluded from these analyses. The cumulative CRC risk was increased for the siblings and the parents of the adenoma probands compared with the spouse controls, especially when the adenoma proband was diagnosed before the age of 60 (Figure 4). These results in the family members of the adenoma patients replicated that of Fuchs32 and St John33 in family members of CRC cases.

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of colorectal cancer in siblings of adenoma patients by the age of diagnosis of adenomas of the National Polyp Study proband, the younger the age of the adenoma diagnosis, the higher the risk of colorectal cancer in the siblings. Spouses of the patients were controls (From Figure 1 of Winawer et al.3)

Challenge now: How can the identification of an advanced adenoma in a patient be used clinically?

The NPS data provided the initial rationale that a premalignant polyp identified in a proband at a young age increased the CRC risk of first-degree relatives (FDRs) who should begin screening at a younger age and by colonoscopy. Recent evidence20 indicated that it is the advanced adenoma that is the significant familial risk determinant rather than a nonadvanced adenoma.34, 35 The 2017 Multi-Society Task Force on CRC screening recommended that an individual with a first degree relative with an advanced adenoma or CRC should begin screening at age 40 years.19. This is important, but a family history of a pathology documented advanced adenoma is often difficult to ascertain. Guidelines should also emphasize that increased risk screening should be recommended in FDRs of patients having an advanced adenoma resected.

Challenge then: How can a comparison of 2 surveillance examinations double contrast barium enema and colonoscopy be assessed in the NPS model?

Due to its greater safety and lower costs, the double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) was considered appropriate for postpolypectomy surveillance and was being used clinically in the 1970s. No blinded comparison of the 2 modalities (DCBE and colonoscopy) had been reported. A prospective comparison of DCBE and colonoscopy was incorporated into the NPS in which the endoscopist withdrew the scope by colonic segments and reported observations to a coordinator who knew the DCBE findings whereas the endoscopist was “blinded” to the DCBE report. If the DCBE was positive and the colonoscopy was negative, an “unblinded “reexamination of the segment was done.4 DCBE detected only one third of the adenomas and missed half of the adenomas larger than 1 cm found on colonoscopy. The results reduced the value of DCBE in postpolypectomy surveillance and in screening, as well as in the diagnostic workup of patients with a positive stool occult blood test (FOBT) or flexible sigmoidoscopy.36 Colonoscopy as the preferred surveillance and diagnostic test was incorporated into guidelines after this study.15 The blinded, unblinded colonoscopy in the NPS also enhanced the quality of the examination because the endoscopist was aware that a DCBE had been done approximately 2 weeks before the colonoscopy and that the results would be unblinded by the coordinator. Additional colonoscopy quality measures included cecal landmarks identification and segmental and total colon clearance by the endoscopist based on optimal visualization and adequacy of preparation. Repeat colonoscopy to clear all polyps and reach the cecum was done in 13% of randomized patients. The high quality of colonoscopy was critical to the CRC prevention.2, 4

Challenge now: Can the NPS blinded/unblinded model can be used to evaluate new modalities of screening and surveillance

Newly introduced examinations could be evaluated using the NPS blinded/unblinded design. One such test, CT colonography, was compared with colonoscopy for the detection of polyps by using the NPS segmental blinded unblinded model.37, 38 The model can also be to evaluate the accuracy of newer methods for examination of a colon. The NPS postpolypectomy model was also used in several primary prevention studies that would otherwise require large cohorts followed for a long time to evaluate CRC incidence and mortality. The NPS design, randomizing a smaller cohort into the intervention and control, groups, with the advanced adenomas as the endpoint was adopted as a more feasible alternative by many studies. Assessed interventions included fiber, calcium, celecoxib, and aspirin.39

Challenge then: To develop a clinically meaningful pathology outcome measure as a substitute for CRC?

The cohort size permitted by the available funding for the NPS did not permit a large enough study in which CRC could be an outcome measure. Therefore, we needed to identify an intermediate CRC surrogate outcome measure. The studies by Muto et al11 suggesting that adenoma size and villous pathology correlated with concomitant CRC was the basis of our decision to incorporate an advanced adenoma as a CRC surrogate measure. In 1990 NPS reported a statistical analysis of the pathological characteristics of adenomas accrued to the study database, which demonstrated a stepwise progression of risk for prevalent high-grade dysplasia, the penultimate precursor to invasive adenocarcinoma, that correlated independently with increasing size and acquisition of a villous component. This provided a further underpinning for the concept of the advanced adenoma having villous features or large size, or high-grade dysplasia as a surrogate outcome measure.6 We incorporated the advanced adenoma as an outcome measure in the NPS design in 1977 based only on the cross-sectional relationship of adenoma pathology with CRC.11 Atkin’s report in 199221, which reported follow-up data on the relationship of rectosigmoid adenoma pathology to subsequent CRC, further validated the advanced adenoma as a surrogate cancer indicator.

Challenge now: Will larger trials with longer follow-up and CRC as the outcome measure validate the advanced adenoma CRC surrogate indicator as an important target for screening and surveillance?

With the benefit and CRC risk provided by the NPS, the research environment changed. Larger studies were funded. However, what is needed are long term studies of varying surveillance intensity to better elucidate the surveillance required for low- and high-risk patients. The European Polyp Surveillance Study (EPoS) is one such study,14 which when completed, can inform the relationship of the advanced adenoma to CRC as an outcome measure, and as a continued valid screening goal. In this randomized clinical trial, EPoS included both nonadvanced and advanced adenomas and the cancer outcome observations for shorter and longer surveillance intervals.14

Can the NPS Model be Used to Address Additional New Challenges?

When the NPS was underway, flat adenomas and serrated polyps were not in the endoscopists or pathologist’s lexicon of polyps. However, a retrospective review of the archived pathology allowed us to document the prevalence and associated findings of these new entities among the cohort. Neither the sessile serrated polyp or the flat adenoma was associated with a higher rate of high-grade dysplasia in synchronous or metachronous adenomas.6, 9 This is being further evaluated.14, 20

Conclusions:

The NPS introduced the postpolypectomy surveillance model and proved that removing adenomas prevented lethal CRC. This provided the rationale for guidelines to recommend screening colonoscopy, for RCTs to be initiated to study its effectiveness, and for the goal of CRC screening to focus on both CRC prevention as well as detection of early stage CRC. The NPS model demonstrated that the lengthening of postpolypectomy surveillance intervals was safe and effective, which provided the rationale for guidelines to recommend less-frequent and risk-based surveillance, and for RCTs to be initiated for further study of safety and effectiveness. This has become increasingly critical considering the proliferation of screening worldwide with use of higher-definition endoscopes with quality benchmarks, and with the dual goal of screening (prevention and early detection), which has resulted in a large population of patients that require surveillance. The sequence of strong scientific studies of both screening and surveillance, followed by evidence-based clinical guidelines is critical for addressing continued challenges to CRC control.23

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge the institutional centers Principal Investigators who made this trial possible: John H. Bond, MD, Walter Hogan, MD, Joel F. Panish, MD, Melvin Shapiro, MD, Frederick Ackroyd, MD; Pathology Review: Leonard S. Gottlieb, MD, Stephen S. Sternberg, MD, Edward T. Stewart, MD (Radiology PI), and Martin Fleisher, PhD (FOBT Laboratory PI). We also thank the patients who participated in this study and the research and clinical staff who managed the study.

Funding: P30 CA008748, U01 CA 199335, R01 CA26852, and R01 CA 46940

Abbreviations:

- ACG

American College of Gastroenterology

- AGA

American Gastroenterology Association

- ASGE

American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- DCBE

Double Contrast Barium Enema

- EPoS

European Polyp Surveillance Study

- FOBT

Fecal (stool) occult blood test

- FIT

Fecal immunochemical test

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- NPS

National Polyp Study

- RCT

Randomized clinical trial

- SEER

Surveillance and End Results

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest for this article

References:

- 1.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, O'Brien MJ, Ho MN, Gottlieb L, Sternberg SS, et al. Randomized comparison of surveillance intervals after colonoscopic removal of newly diagnosed adenomatous polyps. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:901–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Gerdes H, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer in the families of patients with adenomatous polyps. National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winawer SJ, Stewart ET, Zauber AG, Bond JH, Ansel H, Waye JD, et al. A comparison of colonoscopy and double-contrast barium enema for surveillance after polypectomy. National Polyp Study Work Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1766–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O'Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien MJ, Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Diaz B, et al. The National Polyp Study. Patient and polyp characteristics associated with high-grade dysplasia in colorectal adenomas. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:371–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Stewart ET, et al. The National Polyp Study. Design, methods, and characteristics of patients with newly diagnosed polyps. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. Cancer. 1992;70(5 Suppl):1236–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG. The advanced adenoma as the primary target of screening. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:1–9, v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brien MJ, Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Bushey MT, Sternberg SS, Gottlieb LS, et al. Flat adenomas in the National Polyp Study: Is there increased risk for high-grade dysplasia initially or during surveillance? Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2004;2:905–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockhart-Mummery H, Dukes C. The pre-cancerous changes in the rectum and colon. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1928;46:591–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muto T, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. The evolution of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1975;36:2251–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, Godlee F, Stolar MH, Mulrow CD, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zauber A, Winawer S, Bond J, Waye J, Schapiro M. Can surveillance intervals be lengthened following colonoscopic polypectomy? . Gastroenterology. 1997;112:A50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jover R, Bretthauer M, Dekker E, Holme Ø, Kaminski MF, Løberg M, et al. Rationale and design of the European Polyp Surveillance (EPoS) trials. Endoscopy. 2016;48:571–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, Bond J, Burt R, Ferrucci J, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Fletcher RH, Stillman JS, O'Brien MJ, Levin B, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1872–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2008;58:130–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients From the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:307–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, et al. Recommendations for Follow-Up After Colonoscopy and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:415–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkin WS, Morson BC, Cuzick J. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after excision of rectosigmoid adenomas. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:658–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stryker SJ, Wolff BG, Culp CE, Libbe SD, Ilstrup DM, MacCarty RL. Natural history of untreated colonic polyps. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1009–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winawer SJ. The history of colorectal cancer screening: a personal perspective. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:596–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, Løberg M, Zauber AG, Regula J, Kuipers EJ, et al. Population-Based Colonoscopy Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176:894–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aronsson M, Carlsson P, Levin L, Hager J, Hultcrantz R. Cost-effectiveness of high-sensitivity faecal immunochemical test and colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2017;104:1078–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zauber A, Winawer S, Loeve F, Boer R, Habbema D. Effect of initial polypectomy versus surveillance polypectomy on colorectal cancer incidence reduction: microsimulation modeling of National Polyp Study Data. Gastroenterology. 2000;A187:1200. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meester RGS, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Knudsen AB, Ladabaum U. High-Intensity Versus Low-Intensity Surveillance for Patients With Colorectal Adenomas: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2019;171:612–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grady D Report Affirms Lifesaving Role of Colonoscopy. Access Date: September 11, 2020 Published: The New York Times; 2012. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/23/health/colonoscopy-prevents-cancer-deaths-study-finds.html. [Google Scholar]

- 29.A Test in Time. Access Date: September 11, 2020 Published 2012. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/25/opinion/a-test-in-time.html.

- 30.Quintero E, Castells A, Bujanda L, Cubiella J, Salas D, Lanas Á, et al. Colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical testing in colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dominitz JA, Robertson DJ, Ahnen DJ, Allison JE, Antonelli M, Boardman KD, et al. Colonoscopy vs. Fecal Immunochemical Test in Reducing Mortality From Colorectal Cancer (CONFIRM): Rationale for Study Design. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1736–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Speizer FE, Willett WC. A prospective study of family history and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1669–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.St John DJ, McDermott FT, Hopper JL, Debney EA, Johnson WR, Hughes ES. Cancer risk in relatives of patients with common colorectal cancer. Annals of internal medicine. 1993;118:785–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng SC, Lau JY, Chan FK, Suen BY, Tse YK, Hui AJ, et al. Risk of Advanced Adenomas in Siblings of Individuals With Advanced Adenomas: A Cross-Sectional Study. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:608–16; quiz e16-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng SC, Kyaw MH, Suen BY, Tse YK, Wong MCS, Hui AJ, et al. Prospective colonoscopic study to investigate risk of colorectal neoplasms in first-degree relatives of patients with non-advanced adenomas. Gut. 2020;69:304–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fletcher RH. The end of barium enemas? N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1823–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson CD, Chen MH, Toledano AY, Heiken JP, Dachman A, Kuo MD, et al. Accuracy of CT colonography for detection of large adenomas and cancers. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1207–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, Butler JA, Puckett ML, Hildebrandt HA, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, Redston M, Solomon SD, Kim K, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:873–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]