Abstract

Following decades of decline, maternal mortality began to rise in the United States around 1990—a significant departure from the world’s other affluent countries. By 2018, the same could be seen with the maternal mortality rate in the United States at 17.4 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births. When factoring in race/ethnicity, this number was more than double among non-Hispanic Black women who experienced 37.1 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births. More than half of these deaths and near deaths were from preventable causes, with cardiovascular disease being the leading one. In an effort to amplify the magnitude of this epidemic in the United States that disproportionately plagues Black women, on June 13, 2020, the Association of Black Cardiologists hosted the Black Maternal Heart Health Roundtable—a collaborative task force to tackle the maternal health crisis in the Black community. The roundtable brought together diverse stakeholders and champions of maternal health equity to discuss how innovative ideas, solutions and opportunities could be implemented, while exploring additional ways attendees could address maternal health concerns within the health care system. The discussions were intended to lead the charge in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality through advocacy, education, research, and collaborative efforts. The goal of this roundtable was to identify current barriers at the community, patient, and clinician level and expand on the efforts required to coordinate an effective approach to reducing these statistics in the highest risk populations. Collectively, preventable maternal mortality can result from or reflect violations of a variety of human rights—the right to life, the right to freedom from discrimination, and the right to the highest attainable standard of health. This is the first comprehensive statement on this important topic. This position paper will generate further research in disparities of care and promote the interest of others to pursue strategies to mitigate maternal mortality.

Keywords: cardio-obstetrics, mortality, postpartum period, pregnancy, race, social determinants of health

Despite being one of the more advanced health care systems in the world that spends ≈$111 billion per year on maternal, prenatal, and newborn care, the United States has some of the worst rates of maternal and infant health outcomes.1 Globally, maternal mortality rates are decreasing; however, in the United States, the maternal morbidity and mortality rates are rising.2 One of the key factors driving the rise is due to maternal deaths endured by non-Hispanic Black women, who have more than double the rates at 37.1 per 100 000 live births compared with non-Hispanic White (14.7) and Hispanic (11.8) women. This is consistent with earlier data.3 The leading cause of mortality includes cardiomyopathy and cardiovascular conditions such as coronary artery disease, pulmonary hypertension, acquired and congenital valvular heart disease, vascular aneurysm, hypertensive cardiovascular disease (CVD), Marfan syndrome, conduction defects, vascular malformations, and other forms of CVD, with preeclampsia, eclampsia, chronic hypertension, and superimposed preeclampsia categorized separately. Collectively, this makes up 39.2% of mortalities, out of which 63% to 68% are preventable depending on one’s race/ethnic makeup.

There is no singular reason for the increase in maternal mortality disproportionally seen in Black communities. Lack of access to quality and affordable health care along with long-standing health disparities plays a role. However, for Black people and communities of color, these factors are compounded by systemic discrimination and implicit racial bias in medical treatment that can lead to suboptimal care. Recent societal events have emphasized these health disparities that have plagued Black people for centuries. This includes the disproportionately higher rates of severe illness from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the Black community and the overpolicing and brutality against Black people that the nation has witnessed in the media. These events, among others, bring reason to the historical legacy of mistrust that still remains today and negatively affects care delivery.

The Association of Black Cardiologists, Inc (ABC), founded on the premise to address the disproportionate burden of CVD and inequities in cardiovascular care for Black people, has made a commitment to lead initiatives centered around underrepresented minorities. With the maternal health crisis disproportionately affecting this group, ABC is proud to be the cardiovascular society at the forefront in addressing the disparate maternal morbidity and mortality crisis.

In an effort to do so, the ABC hosted the Black Maternal Heart Health Roundtable—a collaborative task force to tackle the maternal health crisis in the Black community. The discussions from the roundtable, which convened on June 13, 2020, were intended to lead the charge in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality through advocacy, education, research, and collaborative efforts. Below is a summary of topics discussed. Central to the discussion was the impact the social determinants of health (SDOHs) have on health care delivery, along with the current barriers seen at the community, patient, and clinician level. With that, the goal of this position paper is to summarize these discussions and coordinate effective solutions to reduce these statistics in our highest risk populations.

At the Heart of the Black Maternal Health Crisis: Critical Risk Factors

The US maternal mortality rate, defined as the number of maternal deaths per 100 000 live births, has increased from 7.2 to 17.4 per 100 000 live births (≈150% increase) between the years 1987 and 2016.4 As described, leading these rates are peripartum cardiomyopathy.5 Thereafter, we see embolic events, hemorrhage, and hypertension. Additional studies have demonstrated that chronic comorbidities and chronic heart disease are the greatest culprits.6,7 The vast majority of these conditions and comorbidities include advanced maternal age along with preventable causes that disproportionately affect women of color, such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes, poor physical activity, unhealthy eating habits, and constant societal stress. With these, Black women are 3 to 4× more likely to die a pregnancy-related death as compared with White women.8

Furthermore, race, ethnicity, and SDOH can increase the risk for such conditions as gestational diabetes, peripartum cardiomyopathy, cesarean deliveries, preterm deliveries, and a low-birth-weight infant, while independently increasing the risk of future CVD.9 SDOH or conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age are the biggest drivers of health beyond the scope of health care alone. These factors such as socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, social support networks, and access to health care make up 60% of health outcome–contributing factors, ultimately impacting health care organizations and the delivery of care.10 Studies demonstrate that although SDOH can have a significant impact on such CVD risk factors, some of them, such as socioeconomic status, cannot explain the Black maternal health crisis.3 For example, although low-income women are at the highest risk of poor outcomes, Black women across the income spectrum have the highest mortality overall. In a study done in New York City, Black women were actually at a higher rate of harm than their White counterparts even when they were college educated and were from the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods.11

Evidence strongly supports the impact structural racism continues to have on our health care sector.8,12 This has been demonstrated best by the strong Black woman or Superwoman role. This is a phenomenon and multidimensional culture-specific framework characterizing psychosocial responses to stress among Black women.13 It works to counteract negative societal characterizations of Black woman and highlight attributes that exist through ongoing oppression and adversity. Recently, Allen et al examined whether this Superwoman schema modified an association between racial discrimination and allostatic load (ie, cumulative biologic stress). The results demonstrated several aspects that could have a negative impact and contribute to Black women’s susceptibility to health problems. As an example, having an intense motivation to succeed and feeling an obligation to help others seemed to worsen the physical harm already endured from racism-induced stress.14 As such, the legacy of strength in the face of stress might have something to do with the current health disparities that disproportionately plague Black women. A formal descriptive framework identifying the mechanisms between stress and health in this population would enhance the understanding of the Superwoman role and the potential causation to the maternal health crisis.

Ways to Incite Change: a Collaborative Community Approach to Maternal Care

Preconception Counseling

Preconception counseling is defined as health education and promotion. The goal of preconception care is risk assessment and intervention before pregnancy to reduce the chances of poor perinatal outcomes. Preconception counseling targeted at the mother, father, and family has been shown to reduce maternal and infant morbidity and mortality.15

A study examining preconception risk factors most associated with adverse birth outcomes found that the majority of women (52%) had at least 1 risk factor, and ≈20% had ≥2 of these risk factors.16 These risk factors including obesity, at-risk drinking, smoking, diabetes, and frequent mental distress remain to be modifiable and preventable, emphasizing its importance.

Structural racism has left Black women vulnerable, marginalized, and most susceptible to the SDOHs that place them at the highest risk of these conditions. Optimizing these risks is an important step in improving health disparities and long-term outcomes through health education and promotion. Despite the fact this education usually starts with the clinician, it should not end there; the local and national community must play a pivotal role.

Community Outreach Programs

Outreach programs that involve the community in a team-based care delivery model are proven strategies to impact outcomes. For instance, the barbershop-based National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–funded study demonstrated an effective intervention among Black male barbershop patrons with uncontrolled hypertension. By incorporating health promotion from their barbers in the community, there was a larger blood pressure (BP) reduction when coupled with medication management by specialty-trained clinical pharmacists.17 This approach, although proven effective, involves meeting the community on their own turf and instilling a sense of comfort and trust by the patrons in their care provider and local pharmacist.

Faith-Based Community Partnership

Trust is an important factor needed for a successful patient-provider relationship. On the contrary, medical distrust may play a role in decision-making. Fortunately, the faith-based community can help Black women bridge this trust with their providers. Churches and other facilities of worship can serve as a point of contact to house and disseminate the promotion of pertinent information. It can serve as a reference to the communities and fill the gaps in care, as to best address access, and change the status quo.

Media’s Role

From the conventional media’s standpoint, it is critical to recognize that resources provided to readers, especially geared toward Black women, can help expose and address disparate issues. An example of this was emphasized by the successful “Black Maternal Mortality Series” published by the SELF magazine in 2020. The objective of this 11-part editorial was to provide information to Black mothers-to-be regarding the preconception, antepartum, and postpartum periods.18 The personal experiences of the editors, many of whom were women of color, led to the recognition of the importance of writing about this topic and gave a deeper understanding of the crisis. This is just one example and a proof of concept as to why the media needs to become more diversified.

Although there has been progress to this effect, women, especially women of color, unfortunately are less likely to be on staff at major media publications. Steps to encourage diversity should include ensuring that more women of color have a seat at the table. In addition, measures need to be taken to ensure their colleagues are open to publishing such inclusive stories. These various steps are methods that can be instilled in the workforce, to ensure representation of the diverse audience within the United States is met.

Additionally, it is imperative that the media and health care sector collaborates. This can be executed by highlighting stories of public figures. These figures can bring a common face to the condition and raise awareness for the number of women of color who idolize them. Such highly influential Black women who have been open and honest about their maternal struggles include Serena Williams, Beyoncé Knowles-Carter, and the former first lady of the United States, Mrs Michelle Obama. In her autobiography “Becoming,”19 Mrs Obama addresses her fertility problems and eventual use of in vitro fertilization. Although a topic associated with stigma, especially in the Black community where it may be perceived as taboo, it’s becoming an increasingly used procedure to help with fertility and assist with conception.

The reality is that infertility is more likely to affect minorities, the poor, and those with less formal education. In fact, Black women, who have higher rates of uterine fibroids, are almost twice as likely as White women to experience infertility.20 Despite this, Black women wait twice as long as White women to seek medical insight on their condition and are less likely to consider treatment options.21 One reason for these disparities is that outreach is less likely to target the Black community, perhaps as many clinicians have internalized the stereotype assuming that White women are most at risk for infertility. As a result, Black women are less likely to be referred to a reproductive endocrine specialist. This makes the news of Mrs Obama’s miscarriage and eventual in vitro fertilization treatment especially significant. Even more so, as infertility and failed fertility therapy are suggested to be risk factors for future CVD.

ABC’s Path to Tackling the Maternal Health Crisis: Past, Present, and Future Overview

ABC and Black Maternal Heart Health

In the year 2000, Bristol Myers Squibb donated $2 million to the ABC to establish the Center for Excellence in Women’s Health and the Center for Epidemiology. The mission of these centers was to address women’s health and expose and address disparities. Since that time, registries were developed to build data and statistics from real-world experience of the providers at the front line. As a culmination of their efforts, “The Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC) Cardiovascular Implementation Study (CVIS): a Research Registry Integrating Social Determinants to Support Care for Underserved Patients” was published in 2019.22 The study demonstrated the importance of integrating real-world electronic health data, with an emphasis upon incorporating patient engagement during practice and day-to-day care. The key to impacting the maternal crisis is incorporating the same approach with quality, education, and outreach and gathering data in a repository to answer relevant questions for these women.

Given its long-term focus on policy and CVD in women, more recently in 2020, the ABC became one of the stakeholder organizations within the Black Maternal Health Caucus. The caucus was launched by congresswoman Alma Adams (of North Carolina) and Lauren Underwood (of Illinois) to increase awareness of Black maternal health and to develop strategies to provide more culturally competent care. As a result of their work, members of the Black Maternal Health Caucus introduced the Black Maternal Health Momnibus, 11 new bills, each addressing unique dimensions of the Black maternal health crisis.23 The ABC continues to support this legislative effort and uses its various platforms to advocate for ongoing congressional provision.

Roundtable Discussion: Key Steps to Improving Black Maternal Health

Multiple issues must be addressed when undertaking the societal racism, institutional racism, and need for more available prenatal care services. A patient-centered approach is one way to tackle these issues.

Acknowledge Black Mother’s Concerns

According to the organization 4Kira4Mom—founded with the mission to advocate for improved maternal health policies, regulations, and education—the core reason Black mothers receive suboptimal care is that their symptoms are being disregarded. A prime example is reflected with the passing of Mrs Kira Johnson, who was admitted to the hospital for a routine cesarean section and thereafter had complications of intractable intra-abdominal pain due to severe postpartum hemorrhage. Unfortunately, her complaints and symptoms were dismissed for 12 hours while awaiting a computed tomography scan; she ended up dying as a result. The story, theme, and unfortunate outcomes are consistent. However, the patient changes from one Black woman to another. The thread that connects these cases is the fact that Black women are not treated to the same degree as non-Black women are treated. One can conclude that had Kira been White, she would still be alive. Standardized, high-quality health care must be implemented, while implicit bias and racism abolished. For Black and other women of color, from Beyoncé Knowles-Carter to Serena Williams, their experiences with being systemically minimized or dismissed due to racism and bias clearly go beyond the socioeconomic boundaries.

Hospital Data Collection and Value-Based Models

Insurance companies must hold institutions accountable by collecting and reviewing data on patients’ morbidity and mortality outcomes, including the race/ethnicity of the provider. Research has shown that patient-physician racial concordance has led to improved quality of care with greater interpersonal trust, satisfaction with care, loyalty and satisfaction with the physician, self-reported health improvement, and willingness to give the physician control in the relationship.24 To this point, the hospitals should provide lists that include the race/ethnicity of the provider, as this allows the patient the flexibility to choose a provider they best identify with. Ultimately, information on the quality of care should also be collected and must be evaluated to establish whether patients are being treated equally. In the end, a value-based arrangement may be a potential method to hold providers accountable with quality metrics that can be evaluated across the patient care continuum. This model has been proposed by the Black Maternal Health Momnibus, which advocated for efforts to improve data collection processes and quality measures along with the promotion of innovative payment models to incentivize high-quality maternity care.23 To promote support from insurance companies, there should be encouragement to increase the pipeline of diversity by having every insurer involve Black, Hispanic, and other diverse leaders that represent the diverse patient demographic that makes up the United States

Strategies to Improve Awareness at a Digital, Industry, and Clinician Level

Prenatal/Antepartum Care

The reproductive period is a very important transitional time, whereby multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO) may emerge. The placenta is a representation of endothelium and reflects the vasculature of the maternal patient. To this point, it is hypothesized to cause some of these APOs, such as preeclampsia, preeclampsia with severe features, eclampsia, or preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension.25 The American Heart Association has already recognized these conditions as independent risk factors for CVD and introduced these complications of pregnancy in the algorithms for the evaluation of future cardiovascular risk scores.26 These are classified as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, in addition to gestational hypertension, defined as new-onset hypertension after 20 weeks of gestation, or chronic hypertension. Other APOs include small for gestational age or fetal growth restriction, as well as preterm birth, placental abruption, and stillbirth. Any one of these APOs that mothers may be systemically exposed to during their reproductive time could lead to underlining pathophysiology that impacts maternal prenatal and antepartum care and makes them more vulnerable to future cardiovascular events.

New Models of Antepartum Care (Cardio-Obstetrics and Potential Extenders)

The development of toolkits that improve the quality of care and impact maternal outcomes has a proven track record. The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative is a multistakeholder organization committed to ending preventable morbidity, mortality, and racial disparities in California maternity care.27 California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative uses research, quality improvement toolkits, state-wide outreach collaboratives, and its innovative Maternal Data Center to improve health outcomes for mothers and infants. Founded in 2006 at the Stanford University School of Medicine together with the State of California in response to rising maternal mortality and morbidity rates, California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative demonstrated maternal mortality decline by 55% between 2006 and 2013, while the national maternal mortality rate continued to rise.

On a national level, a collaborative with the American Heart Association and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists to mitigate the rising maternal morbidity and mortality crisis in the United States lead to the joint publication of a presidential advisory on recommendations to reduce disparities28 via early identification of traditional and sex-specific risk factors for future CVD. With CVD the leading cause of death in women, the advisory was considered an urgent call to action, especially among providers who primarily deliver care to this population. The advisory suggested to screen for conditions that pose a greater future risk to patients, along with the promotion of collaborative management with a maternal heart team.

This team should include obstetricians, perinatologists, cardiologists, anesthesiologists, and, depending on the case, geneticists and intensivists. This should be extended to also include primary care and family medicine clinicians, who can prevent any gaps and promote ongoing care in the postpartum period. Similarly, the early engagement of pediatricians who can help focus on primordial prevention in early adolescents may lead to further optimal health. Just as important is the collaboration with emergency medical professionals who see this patient population in the acute period. By ensuring the emergency medical professionals feel comfortable with the alarming signs, symptoms, and diagnosis of CVD during pregnancy and the postpartum period, this allows for rapid diagnosis and improved management of this vulnerable cohort. To help with this, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative created algorithms that best identify when higher level of care and consultative services with cardiology or perinatology may be required.27

Postpartum Care

Postpartum care is important for monitoring the health of women with chronic illness and as a means to link vulnerable women with the health system. Having limited to no prenatal care and late entry into antepartum care are correlated with patients being less likely to attend the postpartum visit.29 As such, caring for the patient throughout the care continuum (from preconception to postpartum) is important.

Black women are more prone to barriers that limit effective postpartum care. These include cost, transportation, childcare, lack of meaningful communication with providers, and thus limited health literacy. These barriers, in addition to the constant structural and systemic stressors experienced, can translate into premature biological aging and poor health outcomes. To mitigate this, institutions have targeted more modernized approaches to the delivery of care. With hypertension affecting 1 in 10 pregnancies and often persisting in the postpartum period, the use of self-monitored ambulatory BP machines may be a consideration. This was looked at in a randomized clinical trial30 and was proven effective with better control even through 6 months postpartum. A study took ambulatory self-monitoring one step further and focused on the possibility of racial differences.31 What it showed was that the use of a text message–based remote BP monitoring program in the early postpartum period was effective in the Black population (33% of participation from patients undergoing BP readings in the office setting [relative risk, 1.95 (95% CI, 1.3–2.93)] versus 93% of participation of patients undergoing BP readings using text message [relative risk, 0.99 (95% CI, 0.87–1.11)]).

Another important aspect is ensuring patients have close and extended postpartum follow-up. As of May 2018, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists recommended an ongoing process of postpartum care.32 This process known as the fourth trimester would work by replacing the traditional recommendation of a single follow-up appointment at 6 weeks postpartum to that of a follow-up within 3 weeks postpartum and another more comprehensive visit 12 weeks thereafter. This comprehensive visit would be a time to readdress any APO and include screening for mental health concerns.

Moreover, this comprehensive visit allows us to capture the patients at the greatest risk. It also provides an opportunity for referral to a cardiologist so the patient can be seen within 3 months if they experienced an APO.33

The fourth trimester has been recommended to extend up to 1 year postpartum, as 33% of maternal mortality can occur up to 1 year after delivery.4 As a result, several key organizations, including the ABC, the Black Maternal Health Caucus, and Momnibus, have supported the legislation of extending insurance coverage, such as Medicaid services, which normally covers only through 60 days postpartum.32

Role of Industries

Governments, multilateral organizations, and nongovernmental organizations have been expanding efforts in standardizing and improving maternal care. However, the private sector’s role should drive change as well. To address the maternal health issues, Merck launched the Merck for Mothers initiative. Both nationally and globally, Merck for Mothers is a $500 million initiative that leads and collaborates with partners to improve the health and well-being of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period.

From a policy perspective, currently, there is a window of opportunity. Many organizations, including Black Mamas Matter, the Black Women’s Health Imperative, and the Preeclampsia Foundation, have demonstrated extraordinary efforts in educating lawmakers about Black maternal health and making it possible for caucuses such as Representatives Underwood and Adams’ Black Maternal Health Caucus. Before this movement, the Congressional Caucus on Black Women and Girls discussed these issues for several years largely due to the advocacy work and diverse coalition of many such organizations bringing attention to the disparities in maternal mortality rates in the United States. The outcome has impacted dozens of maternal health bills in recent years and resulted in opportunities for some bipartisan and bicameral work. Multiple 2020 candidates who currently serve in congress have introduced bills that have tried to target maternal mortality at the federal level, and they are building upon legislation that passed in 2019, which authorized >$10 million for states to track maternal deaths.

WomenHeart: the National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease—a not-for-profit organization focused on advocacy, national networking of patient support groups, and elevation of patients’ voices and women’s experiences—has a similar dedication to the crisis. With the progression of the policy debate, there is a better understanding of the problems, with racism being at the core. The term racism has come forth and should be classified as a risk factor for health care disparities, specifically when it comes to maternal and heart health.8,34 WomenHeart supports advocating for implicit bias training beginning in medical school curriculums and extending well beyond to the health care workforce.

Medical Training: Diversifying the Field and Changing the Structured Curriculum

Diversifying the medical workforce is imperative to help with this crisis. Currently, although Black people make up 13% of the population, they comprise just about 5% of the active physician workforce. Black female physicians comprise even less, representing only 2% of physicians overall.35 Furthermore, when evaluating female participation in specialties such as CVD, the statistics are just as staggering. The ABC has provided an advisory geared toward program directors within cardiovascular fellowship training programs calling for the promotion of diversity and inclusion. They have also created an “ABC Pipeline Program” aimed to begin targeting middle/high school students and create transparent and plausible paths in the cardiology profession.36 To this same point, it is imperative that as cardiovascular programs begin to change their standardized curriculum to include the expanding cardio-obstetrics field, that emphasis remains on the need to be sensitive when caring for certain patient populations such as racial and ethnic minorities.

Furthermore, modifying medical education is one way to help with these disparities. Societal racism has impacted our education, even as far back as grade school, and needs to be revamped. To address implicit bias, the medical curriculum needs to incorporate additional education as a grassroots approach to incite change. By exposing medical trainees to the history of mistrust their Black patients endured, this will allow the feeling of empathy as a way to become better allies to the diverse patient populations they care for. Providers who are not of color should also receive ongoing cultural competency.

Nurses

Nurses are key players in the multidisciplinary team in the pursuit of lowering poor outcomes and promoting early diagnosis and management. Nurses are encouraged to stay abreast of these issues by identifying the state of maternal health in their respective communities. Nurses wishing to improve maternal outcomes can do so by helping to identify high-risk populations and working with their respective institutions to develop educational programs, outreach initiatives, and quality standards for maternal care. As health care providers, nurses are well-suited to work with multidisciplinary teams to disseminate best practices and advocate for sound public policies focused on alleviating poor maternal outcomes. Additionally, nurses can work with professional/specialty organizations to identify what organizations are doing to address maternal mortality.

Doulas

The use of a doula is invaluable and provides nonclinical, physical, emotional, and informational support. Doulas have been shown to lead to positive outcomes, particularly for women of color.37 They help birthing individuals navigate the complex health care system, as well as help lessen the experience of discrimination many Black people face by advocating for their clients.38 Given the doulas’ ability to understand the needs, values, and cultural congruent care, they ensure birth justice in their training. They help with navigating the tortured and deconstructed health care system and reach patients at their level and community. Unfortunately, doulas are not routinely covered by insurance and are thus underutilized due to inaccessibility. Thus, another approach to improving Black maternal outcomes includes expanding the coverage of doulas.

Midwives

Black midwives were historically known as the granny midwife and identified as individuals who were highly valued, first by their slave owners and then by their community. In the 1920s, the American Medical Association targeted these midwives, eventually leading to the reduction of midwifery births and the increase of hospital-based deliveries.39

Currently, according to the American College of Nurse-Midwives, there are 3 types of certified midwives in the United States These include certified nurse-midwives, certified midwives, and certified professional midwives.

Research shows that midwife care improves maternal and newborn health, reduces rates of unnecessary interventions, and saves money.40,41 It can also fill gaps in care by connecting patients to social services, providing nutritional assistance and using clues and evidence collected to assess a client’s living conditions.

For one, the practice of nurse-midwives has not been based on midwifery. One of the challenges has been the hybridization of nursing and medical knowledge in nurse practitioner education, with the marginalization of nursing knowledge due to the dominant focus of medicine.42 Second, while advance practice nurses (including nurse practitioners and nurse-midwives) developed historically as a community-based, public health need, most only find training and employment in an out-of-hospital or medical office setting. This has led many to feel as though they are only a physician extender, who although trained in practice from the medical model cannot fulfill the full extent of their education and training goals.43 Policies need to be created to formally tackle these obstacles that prevent them from playing an integral role in the health care delivery.

Vulnerable Populations

Historically, the most vulnerable populations see the greatest burden of disease. These populations include women of color ranging from veterans or active military, those who live in rural communities, low-income neighborhoods, or correction institutions.

Women Veterans

Veterans and active military members have one of the greatest health disparities with previously limited access to maternal care. Han et al published a “Call to Action” in Circulation in 2019 focusing on cardiovascular care in women veterans. Per Han et al,44 this growing population is estimated to consist of 2 million women by the year 2025. Data demonstrate that women veterans have a high prevalence of traditional and nontraditional cardiovascular risk factors. Similar to solutions laid out by Han, the Black Maternal Momnibus requested a comprehensive study of the unique maternal health risks facing women veterans and investing in veteran’s maternity care coordination. To the same effect, the Momnibus supported the improvement of maternal health care and support for incarcerated women.23

Rural Communities

Hospitals and obstetrics units are shutting down across rural America, creating a shortage of care that may be contributing to the country’s rising maternal mortality. The use of certified professional midwives, nurses, and doulas, who can provide maternal and newborn care in homes or other out-of-hospital settings, may be one solution to this problem. Evidence shows that when these health care members are integrated into the system, there are improved outcomes. One further solution to this could be the use of innovative technologies, such as telehealth, that may close these gaps and allow women to interact with specialists miles away.

Digital Technology

Telehealth

Tools that support virtual care and diagnosis can benefit some patients with heart disease, while helping clinicians work more efficiently. Despite this, telehealth may not be as valuable to the maternal cohort of women as there is a fear it may contribute to a level of distrust in an already vulnerable population. Telehealth is important, but implicit bias may make it difficult for those without an established and strong patient-provider bond to use.

On the contrary, if done appropriately, telemedicine may help close the gap. For example, as shown by Hirschberg et al,31 remote ambulatory BP monitoring can remove disparities. By eliminating barriers to care and allowing for equitable gathering of data, more knowledge to the health care provider and patient can occur. Remote patient monitoring using self-monitored BP and blood glucose has improved outcomes in patients with chronic health conditions and should remain something that can help pregnant women with CVD even within their antepartum period.45,46

Digital Platforms and Networks

From a technology standpoint, forward-thinking and progressive companies like Mahmee—a HIPAA-secure care management platform—make it easy for payers, providers, and patients to coordinate comprehensive prenatal and postpartum health care from anywhere. The silos between pediatric and obstetric communities are overcome as this platform extends beyond the postpartum period. As such, a community of providers who use this software can empower and deliver a stronger connection between themselves and their patients. Most importantly, this digital network provides the capability to flag and escalate concerns to the primary care provider’s attention and resolve the gaps in care and communication. This may be a good model to expand the communication to another specialist, including those in the cardiovascular field. The ABC CVIS (Cardiovascular Implementation Study) registry integrates patient engagement with remote monitoring.22 This model has demonstrated improved outcomes in underserved patients, including federally qualified centers,22,47,48 and could support interventions in maternal mortality.

Pandemic, Advancing Research Efforts, and Collegial Support

COVID-19

Disasters and pandemics pose unique challenges to health care delivery. Though telehealth will not solve them all, it has become a well-suited scenario in which infrastructure remains intact and clinicians are available to see patients, thus making it one silver lining among the pandemic. But as mentioned above, switching to a telehealth visit may impact the trust among the patient of their provider, particularly in a population that already has a degree of mistrust. In a 50-state survey administered by the American Medical Association, it was believed that a valid patient-physician relationship must be established before the provision of telemedicine services, through most notably a face-to-face examination.49 As pregnancy is a unique time in a female’s life, it is hard to say whether this will affect care in a positive or negative way. As such, more data need to be evaluated.

To date, data demonstrate that the severe forms of COVID-19 are disproportionately affecting Black and other communities of color and may extend to several aspects of maternal care. With COVID-19 layered on top of the health disparities, there is no longer a crack in the earth; it is now a chasm. Discrimination and bias are unearthed, and issues are now laid bare. Although disparity gaps made progress, the racial inequity gap widened. COVID-19 increased a broader understanding of the SDOH and provided a path to drive action.

Collaborative Research and Registry Data in Cardio-Obstetrics

Heart Outcomes in Pregnancy: Expectations Registry

Today, risk estimation through history, physical exam, and previously established risk models remains clinicians’ cornerstone of identifying which patients may require closer antenatal and postpartum surveillance given higher risk for major adverse cardiovascular or obstetric complications. There remain significant gaps in knowledge regarding how pregnancy affects cardiovascular conditions and how cardiovascular conditions influence pregnancy, further highlighting the need for more data.

With the leading cause of morbidity and mortality during pregnancy and the postpartum period being CVD, there is a need to address critical gaps in knowledge and variability in the care of patients with heart disease in pregnancy. As part of a research collaborative and the need to standardize the management of patients with heart disease in pregnancy, an interdisciplinary care registry between cardiologists and obstetricians was developed, the Heart Outcomes in Pregnancy: Expectations.

The Heart Outcomes in Pregnancy: Expectations registry aimed to address key clinical questions surrounding the preconception period, antenatal care, delivery planning and outcomes, and long-term postpartum care and outcomes of these patients.50 The Heart Outcomes in Pregnancy: Expectations registry was geared to help understand ways to improve quality of care in this specialized population. Lastly, Heart Outcomes in Pregnancy: Expectations’s scientific organizations, including the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists, the Heart Failure Society of America, the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and others, have worked collegially and collaboratively to support research dissemination arising from this cardio-obstetric subspecialty by inviting leaders from each field to present at national and international conferences. This support has contributed to further understanding and adoption of best practices in cardio-obstetrics.

NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health

The National Institutes of Health—a part of the US Department of Health and Human Services—is the nation’s medical research agency making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. Through its Office of Research on Women’s Health, there have been several initiatives centered around the improvement of maternal morbidity and mortality; for instance, the development of the Maternal Morbidity and Mortality web portal, which provides trustworthy, science-based information on ways to ensure a healthy pregnancy, delivery, and postpregnancy outcome for scientists, researchers, consumers, and advocates. Additionally, education centered on possible pregnancy-related complications and the impact of chronic conditions (eg, hypertension and diabetes) and what actions women can take to promote a healthy pregnancy have been highlighted. As the primary government agency responsible for biomedical and public health research, the National Institutes of Health has invested about $250 million in maternal health in fiscal year 2017. The National Institutes of Health supports significant research on different aspects of maternal health and has collaborated with many medical societies, including the ABC, to do so.

He for She Allies

To further close the gap and improve maternal care, more male allies in the health care workforce are needed to build awareness and optimal health for women broadly. There should be an intentional partnership between academic, private-sector, and community programs that engage, resonate, and act with a diversity and inclusion advocate. The knowledge base within the health care system, media, industry partnerships, and insurance companies can lead to effective action and encompass solutions for maternal health advocacy, regardless of sex.

Concluding Thoughts

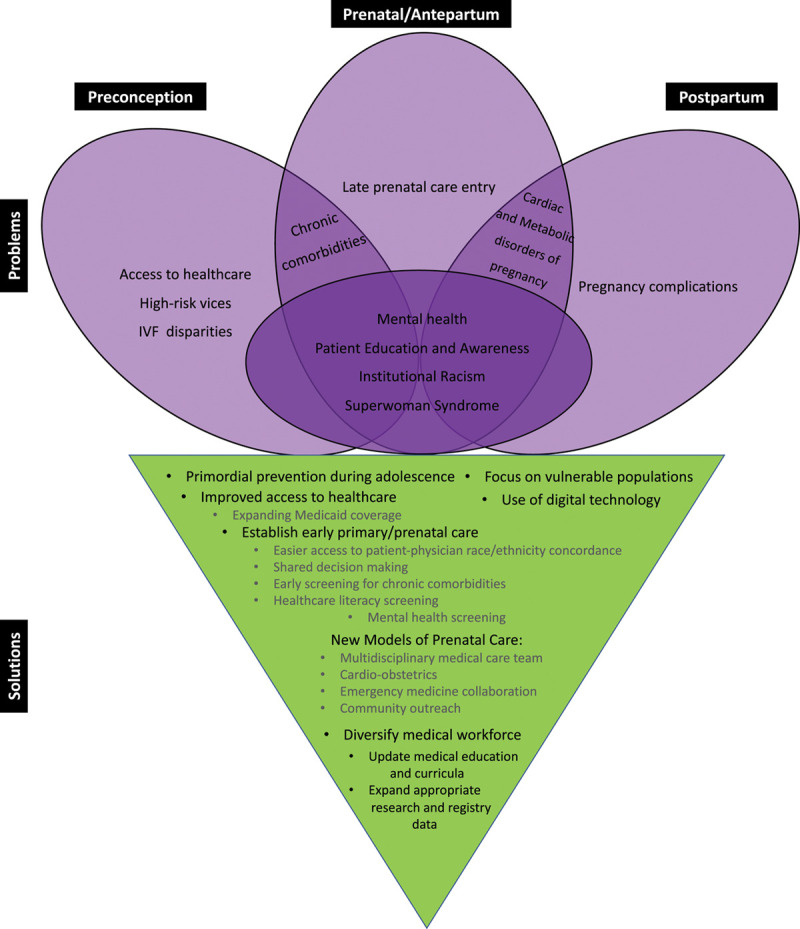

Collaborative care has been shown effective in lowering the staggering numbers of morbidity and mortality seen during pregnancy and the postpartum period, which disproportionately affects Black mothers. A multidisciplinary team and efforts to support the patient during the preconception, prenatal, antepartum, and the postpartum period with the primary care provider, obstetrician, cardiologist, nurse, emergency medical clinician, mental health therapist, ministry, family, doula, midwife, and pediatrician needs to be a standard of practice (Figure).

Figure.

A summary of problems and solutions across the preconception to postpartum care continuum. IVF indicates in vitro fertilization.

Expanding insurance coverage beyond the immediate postpartum period is important. Given that 1 in 8 maternal deaths occur between 42 and 365 days postpartum, extending insurance coverage could be an important first step toward reducing these late maternal deaths, particularly among Medicaid recipients.

To better standardize and deliver high-quality health care, protocols should be utilized, which combine laboratory tests, early consultations, delivery care models, and relieve the burden on a single clinician. Notably now with COVID-19, patients coming into the emergency department have a higher likelihood to lose their advocate. The burden now is upon the providers more than ever to open up the conversation and help fill that lost advocacy to support the patient. As such, extending and standardizing the use of midwives or doulas is essential. Doulas offer evidence-based birth support with current information on breastfeeding and education. The incorporation of community doula programs to health care systems may provide doula support for free or at a reduced cost while we await policy changes for insurance coverage.51

Community education on prevention of cardiovascular risks, signs, and symptoms through newsletters and electronic-blasts along with advocacy for public policy with community outreach to patients, providers, and nurses is essential.

Finally, more research needs to be done, particularly in the rural, military, incarcerated, and underserved communities. Given the current national situation, the curtain has been pulled back and positions the community well for legislative and regulatory actions. The policy window is now open to advance given policy objectives. We know that solving the Black maternal mortality crisis will take unwavering purpose, passion, and commitment, and by having a blueprint in place, it may make navigating this difficult crisis slightly easier.

Acknowledgments

A special acknowledgement to the added roundtable participants and organizations: moderator: Tanzina Vega, host, The Takeaway on WNYC/PRX, Ferris Professor of Journalism, Princeton University. Roundtable participants and contributors: Angela Aina, MPH, Interim Executive Director, Black Mamas Matter Alliance; Rose Aka-James, MPH, National Membership Manager, Black Mamas Matter Alliance; Denise Bolds, Dona Certified Birth Doula, Owner, Bold Doula; Seyi Bolorunduro, MD, MPH, FACC, FSCAI, Interventional Cardiology, Inova Fairfax Hospital; Camille Bonta, MHS, ABC Policy Consultant, Principal, Summit Health Care Consulting; Tammy Boyd, JD, MPH, Chief Policy Officer, Black Women’s Health Imperative; Stephanie Brown, MD, MPH, Emergency Medicine, Sutter’s Atla Bates and Summit Medical Centers; Janine Clayton, MD, Director, NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health; Yvonne Commodore-Mensah, PhD, MHS RN, FAHA, FPCNA, Board of Directors, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Assistant Professor, Community-Public Health Nursing; Mary-Ann Etiebet, MD, Lead and Executive Director, Merck for Mothers; Amy Friedrich-Karnik, Vice President Advocacy and Communications, WomenHeart; Linda Goler Blount, MPH, President and Chief Executive Officer, Black Women’s Health Imperative; Celina Gorre, MPH, MPA, Chief Executive Officer, WomenHeart; Charles Johnson, Founder, 4Kira4Moms; Janet K. Han, MD, FACC, FHRS, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, University of California Los Angeles/VA Greater Los Angeles Medical Center; Melissa Hanna, JD, MBA, Cofounder and Chief Executive Officer, Mahmee: Jennifer Haythe, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Center for Advanced Cardiac Care, Codirector, Cardio-Obstetrics, Program and Women’s Heart Center, Columbia University; Pamela D. Price, Deputy Director, The Balm In Gilead/Healthy Churches 2030; Dr Pernessa C. Seele, Founder and Chief Executive Officer, The Balm In Gilead/Healthy Churches 2030; Leta Shy, Digital Director, SELF magazine; Kim Smith, National Manager of Practice Operation Development and Transitions, Tenet Healthcare, Chair, Preeclampsia Foundation; Sharon Ann Taylor-Smalls, CNM, Nurse Midwife, Owner, Redeemed Creations Midwifery Services, PLLC; David Thompson, Vice President, Clinical Solutions, Cardiac Rhythm Management, Boston Scientific; Eleni Z. Tsiga, Chief Executive Officer, Preeclampsia Foundation; Congresswoman Lauren Underwood, Black Maternal Health Caucus. Participating Organizations: 4Kira4Moms, The Balm In Gilead/Healthy Churches 2030, Black Mamas Matter Alliance, Black Women’s Health Imperative, Boston Scientific, Bold Doula, Heart Outcomes in Pregnancy Expectations Registry Mahmee, Merck for Mothers, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, Preeclampsia Foundation, Redeemed Creations Midwifery Services, PLLC, SELF magazine, VA Greater Los Angeles Medical Center, WomenHeart. ABC Planning Committee: Tierra Dillenburg, Project Manager, Association of Black Cardiologists; Alan J. Merritt, IT/Operations Consultant Association of Black Cardiologists; Rachel Williams, Content, Communications and Community Engagement Association of Black Cardiologists.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

None.

Contributor Information

Kecia Gaither, Email: keciagaithermd@aol.com.

Samar A. Nasser, Email: snasser@gwu.edu.

Michelle A. Albert, Email: michelle.albert@ucsf.edu.

Keith C. Ferdinand, Email: kferdina@tulane.edu.

Joyce N. Njoroge, Email: joyce.njoroge@ucsf.edu.

Biljana Parapid, Email: biljana_parapid@yahoo.com.

Sharonne N. Hayes, Email: hayes.sharonne@mayo.edu.

Cheryl Pegus, Email: pegusc@caluent.com.

Bola Sogade, Email: bsogade@obgyneconsultants.com.

Anna Grodzinsky, Email: agrodzinsky@saint-lukes.org.

Karol E. Watson, Email: kwatson@mednet.ucla.edu.

Cassandra A. McCullough, Email: cmccullough@abcardio.org.

Elizabeth Ofili, Email: eofili@msm.edu.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Strong start for mothers and newborns evaluation: YEAR 5 project synthesis volume 1: cross-cutting findings. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://innovation.cms.gov/files/cmmi/strongstart-prenatal-finalevalrpt-v1.pdf.

- 2.Cox KS. Global maternal mortality rate declines—Except in America. Nurs Outlook. 2018;66:428–429. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html.

- 4.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy-Related Deaths. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-relatedmortality.htm.

- 5.ACOG.. ACOG practice bulletin no. 212: pregnancy and heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;1333:e320–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Moniz MH, Davis MM, Heisler M, Dalton VK. Disparities in chronic conditions among women hospitalized for delivery in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1319–1326. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lima FV, Yang J, Xu J, Stergiopoulos K. National trends and in-hospital outcomes in pregnant women with heart disease in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:1694–1700. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell EA. Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61:387–399. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gadson A, Akpovi E, Mehta PK. Exploring the social determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in prenatal care utilization and maternal outcome. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:308–317. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair IV, Cohen MS, Cruz-Flores S, Davey-Smith G, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Lauer MS, Lockwood DW, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, and Stroke Council. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:873–898. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldman A. New York city launches initiative to eliminate racial disparities in maternal death. 2018. Propublica [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain J, Moroz L. Strategies to reduce disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality: patient and provider education. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:323–328. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods-Giscombé CL. Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qual Health Res. 2010;20:668–683. doi:10.1177/1049732310361892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen AM, Wang Y, Chae DH, Price MM, Powell W, Steed TC, Rose Black A, Dhabhar FS, Marquez-Magaña L, Woods-Giscombe CL. Racial discrimination, the superwoman schema, and allostatic load: exploring an integrative stress-coping model among African American women. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2019;1457:104–127. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler J, Mahdy H, Jack B. Preconception Counseling. In: StatPearls [Internet]. 2020. StatPearls Publishing; Accessed October 11, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441880/. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denny CH, Floyd RL, Green PP, Hayes DK. Racial and ethnic disparities in preconception risk factors and preconception care. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21:720–729. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, Blyler C, Muhammad E, Handler J, Brettler J, Rashid M, Hsu B, Foxx-Drew D, Moy N, Reid AE, Elashoff RM. A cluster-randomized trial of blood-pressure reduction in Black barbershops. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1291–1301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shy L, Braithwaite P, McClain D, Bahadur N, Standard V. Black Maternal Mortality: Examining What We Know About the Public Health Crisis and Where We Go From Here. 2020. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://www.self.com/package/black-maternal-mortality.

- 19.Obama M. Becoming. 2018. 1st ed Crown [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility and impaired fecundity in the United States, 1982-2010: data from the national survey of family growth. Natl Health Stat Report. 20131–18, 1 p following 19. Published online August 14http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24988820. [PubMed]

- 21.Chin HB, Howards PP, Kramer MR, Mertens AC, Spencer JB. Racial disparities in seeking care for help getting pregnant. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29:416–425. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ofili E, Schanberg L, Hutchinson B, Sogade F, Fergus I, Duncan P, Hargrove J, Artis A, Onyekwere O, Batchelor W, et al. The Association of Black Cardiologists (ABC) Cardiovascular Implementation Study (CVIS): a research registry integrating social determinants to support care for underserved patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1631 doi:10.3390/ijerph16091631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Underwood L. Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2020. 116th Congress. 2020. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6142.

- 24.Terlizzi EP, Connor EM, Zelaya CE, Ji AM, Bakos AD. Reported importance and access to health care providers who understand or share cultural characteristics with their patients among adults, by race and ethnicity. Natl Health Stat Report. 2019;130:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melchiorre K, Thilaganathan B, Giorgione V, Ridder A, Memmo A, Khalil A. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and future cardiovascular health. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:59 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, Newby LK, Piña IL, Roger VL, Shaw LJ, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women—2011 update. Circulation. 2011;123:1243–1262. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820faaf8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative: Cardiovascular Disease Care in Pregnancy and Postpartum. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://www.cmqcc.org/projects/cardiovascular-disease-pregnancy-postpartum.

- 28.Brown HL, Warner JJ, Gianos E, Gulati M, Hill AJ, Hollier LM, Rosen SE, Rosser ML, Wenger NK; American Heart Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Promoting risk identification and reduction of cardiovascular disease in women through collaboration with obstetricians and gynecologists: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association and the American College of obstetricians and gynecologists. Circulation. 2018;137:e843–e852. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siddiqui R, Bell T, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Minard C, Levison J. Predictive factors for loss to postpartum follow-up among low income HIV-infected women in Texas. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28:248–253. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cairns AE, Tucker KL, Leeson P, Mackillop LH, Santos M, Velardo C, Salvi D, Mort S, Mollison J, Tarassenko L, et al. ; SNAP-HT Investigators. Self-management of postnatal hypertension: the SNAP-HT trial. Hypertension. 2018;72:425–432. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.10911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirshberg A, Sammel MD, Srinivas SK. Text message remote monitoring reduced racial disparities in postpartum blood pressure ascertainment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:283–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ACOG. Committee opinion number 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140–e150. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho L, Davis M, Elgendy I, Epps K, Lindley KJ, Mehta PK, Michos ED, Minissian M, Pepine C, Vaccarino V, et al. ; ACC CVD Womens Committee Members. Summary of updated recommendations for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2602–2618. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Syverson C, Seed K, Shapiro-Mendoza C, Callaghan WM, Barfield W. Racial/Ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths- United States, 2007-2016. Morb Mortailty Wkly Rep. 2019;68:762–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.College A of AM. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Published 2019. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019.

- 36.Kuehn BM. Association of Black cardiologists calls for urgent effort to address health inequity and diversity in cardiology. Circulation. 2020;142:1106–1107. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lantz PM, Low LK, Varkey S, Watson RL. Doulas as childbirth paraprofessionals: results from a national survey. Womens Health Issues. 2005;15:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Black LL, Johnson R, VanHoose L. The relationship between perceived racism/discrimination and health among Black American Women: a review of the literature from 2003 to 2013. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities. 2015;2:11–20. doi:10.1007/s40615-014-0043-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor J, Novoa C, Hamm K, Phadke S. Eliminating Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Mortality. Center for American Progress. 2019. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2019/05/02/469186/eliminating-racial-disparities-maternal-infant-mortality/.

- 40.American College of Nurse Midwives. Core Competencies of Basic Midwifery Practice. 2020. Accessed on October 11, 2020. https://www.midwife.org/acnm/files/acnmlibrarydata/uploadfilename/000000000050/ACNMCoreCompetenciesMar2020_final.pdf.

- 41.Vedam S, Stoll K, MacDorman M, Declercq E, Cramer R, Cheyney M, Fisher T, Butt E, Yang YT, Powell Kennedy H. Mapping integration of midwives across the United States: impact on access, equity, and outcomes. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192523 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wood SK. Keeping the nurse in the nurse practitioner. Adv Nurs Sci. 2020;43:50–61. doi:10.1097/ANS.0000000000000301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moran KJ, Burson R, Conrad D. The Doctor of Nursing Practie Project: a Framework for Success. 2020. 3rd ed LLC J& BL, ed. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han JK, Yano EM, Watson KE, Ebrahimi R. Cardiovascular care in women veterans. Circulation. 2019;139:1102–1109. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pemu PE, Quarshie AQ, Josiah-Willock R, Ojutalayo FO, Alema-Mensah E, Ofili EO. Socio-demographic psychosocial and clinical characteristics of participants in e-HealthyStrides©: an interactive ehealth program to improve diabetes self-management skills. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(4 suppl):146–164. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ofili EO, Pemu PE, Quarshie A, Mensah EA, Rollins L, Ojutalayo F, McCaslin A, Clair BS. Democratizing discovery health with N=me. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2018;129:215–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown M, Ofili EO, Okirie D, Pemu P, Franklin C, Suk Y, Quarshie A, Mubasher M, Sow C, Montgomery Rice V, et al. Morehouse Choice Accountable Care Organization and Education System (MCACO-ES): integrated model delivering equitable quality care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3084 doi:10.3390/ijerph16173084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pemu P, Josiah Willock R, Alema-Mensa E, Rollins L, Brown M, Saint Clair B, Olorundare E, McCaslin A, Henry Akintobi T, Quarshie A, Ofili E. Achieving health equity with e-healthystrides©: patient perspectives of a consumer health information technology application. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(suppl 2):393–404. doi: 10.18865/ed.29.S2.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Medical Association. 50-state survey: establishment of a patient-physician relationship via telemedicine. 2018. Accessed on October 11, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2018-10/ama-chart-telemedicine-patient-physician-relationship.pdf.

- 50.Grodzinsky A, Florio K, Spertus JA, Daming T, Schmidt L, Lee J, Rader V, Nelson L, Gray R, White D, et al. Maternal mortality in the United States and the HOPE registry. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2019;21:42 doi:10.1007/s11936-019-0745-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wint K, Elias TI, Mendez G, Mendez DD, Gary-Webb TL. Experiences of community doulas working with low-income, African American mothers. Health Equity. 2019;3:109–116. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]