Abstract

Objective:

To determine the length of time following concussion that impaired tandem gait performance is observed.

Design:

Clinical measurement, prospective longitudinal

Setting:

NCAA collegiate athletic facility

Participants:

Eighty-eight concussed NCAA Division I student-athletes and thirty healthy controls.

Independent Variables:

Group (concussion/control) and time (Baseline, Acute, Asymptomatic, RTP)

Main Outcome Measures:

Participants completed four single-task and dual-task tandem gait trials. The concussion group completed tests at the following time points: preseason (Baseline), within 48 hours following concussion (Acute), on the day symptoms were no longer reported (Asymptomatic), and when cleared to return to sports (RTP). Controls completed the same protocol at similar intervals. The dual-task trials involved mini-mental style cognitive questions answered simultaneously during tandem gait. We analyzed the best time of the four trials, comparing groups with a linear mixed model.

Results:

Acutely post-concussion, the concussion group performed single-task tandem gait slower (worse) than controls (Concussion: 11.36±2.43 seconds, Controls: 9.07±1.78 seconds, p<0.001). The concussion group remained significantly slower than controls (9.95±2.21 vs. 8.89±1.65 seconds, p=0.03) at Asymptomatic day but not RTP. There were significant group (p<0.001) and time (p<0.001) effects for dual-task tandem gait. The groups were not significantly different at baseline for single-task (p=0.95) or dual-task (p=0.22) tandem gait.

Conclusion:

Our results indicate that tandem gait performance is significantly impaired acutely following concussion, compared to both preseason measures and controls. Postural control impairments were not present when the student-athletes were cleared for RTP. This information can assist clinicians when assessing postural control and determining recovery following a concussive injury.

Keywords: Gait, Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, Postural Control, Cognitive

Introduction

Impaired postural control is common following concussion, and a combined gait and balance evaluation is recommended as part of a multifaceted approach to concussion assessment.1,2 The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool-3 (SCAT-3) recommends clinicians use tandem gait and/or the modified Balance Error Scoring System (mBESS) to assess post-concussion balance.3 The more recent SCAT-5 still recommends the mBESS as the primary balance assessment. However, the previous SCAT-3 tandem gait protocol of four timed trials has been replaced with the examiner’s subjective evaluation of whether an individual can perform tandem gait normally as part of the neurological screen.4 Subjective assessments, such as the BESS, are designed to identify overt balance deficits after a concussion, and outcomes can vary based on who is conducting the testing.2 Therefore, the timing component of tandem gait allows for the inclusion of an objective outcome, and should continue to be implemented in clinical settings.5-7

Evidence suggests tandem gait is more sensitive and specific than BESS when identifying acute post-concussion postural control deficits.6 Tandem gait, however, remains under-reported in the concussion literature.5,6,8 The BESS evaluates balance in a quiet stance environment, but dynamic tasks may be more suitable for identifying post-concussion postural control impairments.2,6 Tandem gait is a clinically feasible tool to evaluate dynamic balance, speed, and coordination.9-11 The cerebellum receives and processes afferent information from multiple sensory systems via the spinocerebellar pathway and signals to the motor cortex and other control centers to carry out specific motions.12 These signals are sent to the brainstem and relayed to the spinal cord via the vestibulo, rubro, and reticulospinal pathways, which act directly on motor neurons to fine-tune movements to specific tasks, thus playing a key role in the regulation of balance and posture during coordinated movements.12 The nature of the heel-to-toe pattern of tandem gait requires a highly coordinated movement that is adversely affected following concussion.6,8,12

Tandem gait has identified dynamic postural control deficits acutely post-concussion;6,8 however, it is unclear whether these impairments persist throughout clinical recovery and clearance to return to sport participation (RTP). Using instrumented gait tasks, previous studies have observed impairments up to 2 months after concussion, which is beyond typical BESS recovery (3-5 days). 13-16 These lingering deficits are particularly evident during dual-tasks, which combine simultaneous motor and cognitive task execution (i.e. walking and talking). This suggests that including a simultaneous cognitive task and motor task increases the sensitivity to detect post-concussion postural control impairments. Howell et al., examined tandem gait across a 2-month time point following concussion and observed longer-lasting dual-task performance deficits among concussed adolescents compared to controls, demonstrating dual-task tandem gait impairments may also persist beyond clinical recovery.8 However, the study lacked pre-injury data, which was included herein as a more robust examination of post-concussion tandem gait performance. Further, dual-task tandem gait performance may be an appropriate proxy for dual-task gait speed, which is one of several gait metrics useful in identifying post-concussion impairment, but without the demand for expensive technology to administer.17 Therefore, tandem gait may serve as an additional approach for clinicians to assess post-concussion postural control.

Acute tandem gait deficits and lingering steady-state dual-task gait deficits have been identified following concussion, but the effect of concussion on tandem gait from preseason baseline through RTP is unexplored. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine both single-task and dual-task tandem gait performance at clinical milestones (Baseline, Acute, Asymptomatic, RTP) across the post-concussion timeline. We expected no differences between the concussion and control groups at Baseline, but differences across the remaining time points for both single and dual-task tandem gait. Further, we expect the results of this study will demonstrate the utility of tandem gait as a clinical tool across the concussion recovery timeline.

Methods

Participants

We enrolled 88 participants in the concussion group, and 28 healthy controls. (Table 1) Concussed participants were NCAA Division I student-athletes who were healthy at preseason (Baseline) testing and were included in the study if they were diagnosed with a concussion within the study timeframe and had valid baseline data. All concussions were identified by an athletic trainer and diagnosed by a physician in accordance with the criteria established from the 5th International Consensus on Concussion in Sport (CIS).1 Control participants were active, healthy college students with no history of concussion within the past 6 months. Concussion history included both diagnosed, unreported, and undiagnosed concussions, which was determined from a reliable health history questionnaire.18 The exclusion criteria for both groups included any self-reported neurological disorder, current lower extremity orthopedic injury, and metabolic, vestibular, vision, or other disorders that would impair typical gait performance. Participants provided informed consent in accordance with the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Concussion (n=88) |

Controls (n=28) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

20.4 ± 1.5 | 21.2 ± 2.1 | 0.04* |

| Height (cm) |

174.9 ± 11.0 | 171.3 ± 9.2 | 0.12 |

| Mass (kg) |

73.6 ± 17.1 | 74.2 ± 16.0 | 0.89 |

| Concussion History Range (% concussed) |

0-4 (36/88) 40.9% |

0-4 (6/28) 21.4% |

0.07 |

| Sex (M/F) |

34/54 | 15/13 | 0.19 |

| Days Between Injury and Acute Time points | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.65 |

| Days Between Acute and Asymptomatic Time points | 8.3 ± 9.2 | 19.9 ± 11.3 | <0.001* |

| Days Between Asymptomatic and RTP Time points | 7.6 ± 6.5 | 7.8 ± 8.1 | 0.74 |

There were significant differences between the concussion and control groups for age and days between the Acute and Asymptomatic time points.

Procedures

All concussed participants completed tandem gait testing across multiple concussion recovery clinical milestones: prior to the start of their athletic season (Baseline), within 48 hours following concussion (Acute), on the day they no longer reported symptoms (Asymptomatic), and on the day they were cleared to return to full sports participation (RTP). The healthy controls completed testing across four selected time points similar to the concussion group. This timeline is consistent with the post-concussion timeline recommended in the 5th CIS.1

Participants stood behind a starting line and, on a verbal cue, walked forward as quickly and accurately as possible along a 38mm wide, 3-meter long line with an alternate heel-to-toe gait. Instructions were consistent with SCAT-3 guidelines3, which were the current guidelines in effect. Once the participant crossed the opposite end of the line, he or she was instructed to complete a 180-degree turn and return to the starting line with the same heel-to-toe gait pattern. The time was stopped once the participant’s full foot was across the start/end line. To be considered a successful trial, participants could not step off the line or have separation between the heel and the toe. Any unsuccessful trials were repeated; however, this was a rare occurrence, and no participants required more than one repeated trial. A total of 4 trials were completed, for both single-task and dual-task, and the best time out of the 4 trials was recorded. The cognitive tests performed during dual-task trials consisted of 1) reciting the months of the year in reverse order, 2) spelling a five-letter word backwards, and 3) serial subtraction by 6s or 7s from a randomly selected number.8,19 Prior to each dual-task trial, participants were given specific instructions as to which task they were to complete. However, there were no familiarization trials or prioritization instructions given for the cognitive or motor task.

Data Analysis and Statistical Approach

This study utilized a within and between-subjects prospective longitudinal approach, where we compared tandem gait performance across the testing timeline between groups. The independent variables were group (concussion, control) and time (Baseline, Acute, Asymptomatic, RTP). The dependent variables included the best overall time of the four tandem gait trials for single-task, the best overall time for dual-task, and cognitive accuracy (the percentage of correct answers out of the total possible answers) during dual-task tandem gait.

Group demographics were compared using independent sample t-tests and Fisher’s exact test. The dependent variables of interest were compared using linear mixed-effects models to account for missing data at any of the time points. Out of the total combined data set, 43% of the concussion group had complete data (data collected at all four time points), and 64% of the healthy controls had complete data. Significant group x time interactions were followed up with post-hoc testing for fixed effects, which allowed for examination of between group differences at each time point. Our alpha level was set at 0.05, and all statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS.

Results

Single-Task Tandem Gait

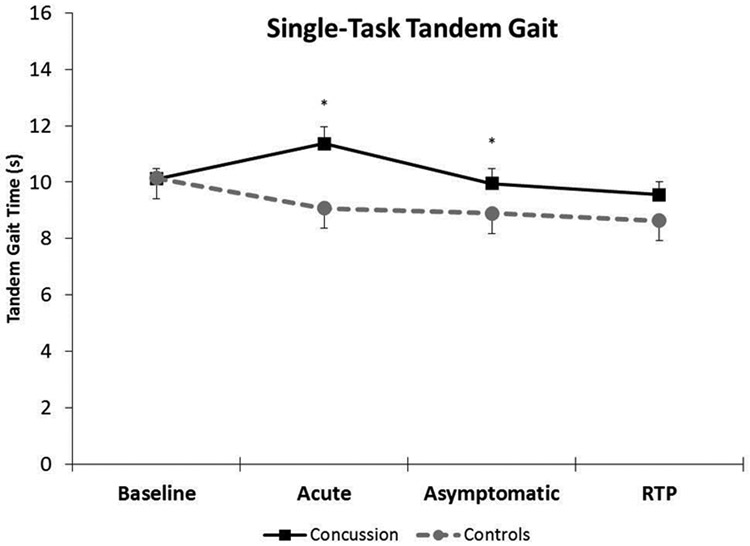

There was a significant group x time interaction (F=4.504, p=0.004) for single-task tandem gait. The concussion and control groups were not significantly different at Baseline (Concussion: 10.12 ± 1.68 seconds, Controls: 10.15 ± 1.97 seconds, p=0.95, Cohen’s d=0.02); however, the concussion group was significantly worse at the Acute (Concussion: 11.36 ± 2.43 seconds, Controls: 9.07 ± 1.78 seconds, p<0.001, Cohen’s d=1.08) and Asymptomatic (Concussion: 9.95 ± 2.21 seconds, Controls: 8.89 ± 1.65 seconds, p=0.03, Cohen’s d=0.54) time points. At RTP, the concussion group (9.56 ± 1.81 seconds) and the controls (8.64 ± 1.73 seconds) were not significantly different (p=0.06). (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Single-task tandem gait performance (mean and 95% confidence interval bars) across the clinical concussion timeline between concussion and control groups. *indicates a statistically significant difference

Within the concussion group, single-task tandem gait performance was significantly worse (1.24 seconds slower) between Baseline and Acute days (p<0.001) but not significantly different between Baseline and Asymptomatic (p=0.61) or Baseline and RTP (p=0.09). Within the control group, single-task tandem gait performance significantly improved between Baseline and the remaining three time points (Acute: 1.08 seconds, p=0.05; Asymptomatic: 1.25 seconds, p=0.03; RTP: 1.51 seconds, p=0.01)

Dual-Task Tandem Gait Motor Performance

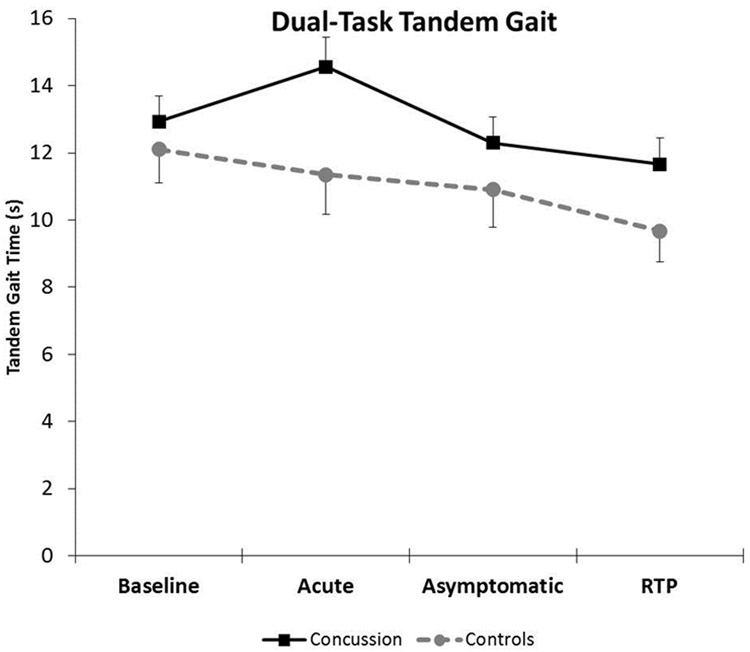

The overall group x time interaction was not significant for dual-task tandem gait (F=2.29, p=0.08). (Figure 2) There was a significant main effect for group (F=27.81, p<0.001) whereby the concussion group performed worse (slower) on tandem gait overall compared to controls. There was also a main effect for time (F=8.17, p<0.001) between the concussion and control groups with tandem gait time improving across Asymptomatic and RTP.

Figure 2.

Dual-task tandem gait performance (mean and 95% confidence interval bars) across the clinical concussion timeline between the concussion and control groups. The dual-task tandem gait times for both groups at each time point were as follows: Baseline (Concussion: 12.93 ± 3.02 seconds, Controls: 12.11 ± 2.74 seconds, p= 0.22, Cohen’s d= 0.28), Acute (Concussion: 14.56 ± 3.14 seconds, Controls: 11.35 ± 3.03 seconds, p<0.001, Cohen’s d= 1.04), Asymptomatic (Concussion: 12.30 ± 2.70 seconds, Controls: 10.90 ± 2.60 seconds, p= 0.05, Cohen’s d= 0.53), and RTP (Concussion: 11.66 ± 2.49 seconds, Controls: 9.67 ± 2.24 seconds, p= 0.003, Cohen’s d= 0.84).

Within the concussion group, dual-task tandem gait performance was significantly worse (1.63 seconds slower) between Baseline and Acute days (p=0.003) and significantly better (1.27 seconds, p=0.03) between Baseline and RTP. The concussion group was not significantly better at Asymptomatic (0.63 seconds, p=0.25). Within the control group, dual-task tandem gait performance was significantly better between Baseline and RTP (2.45 seconds, p=0.002) but not significantly different between Baseline and Acute (0.76 seconds, p=0.33) or Baseline and Asymptomatic (1.22 seconds, p=0.14).

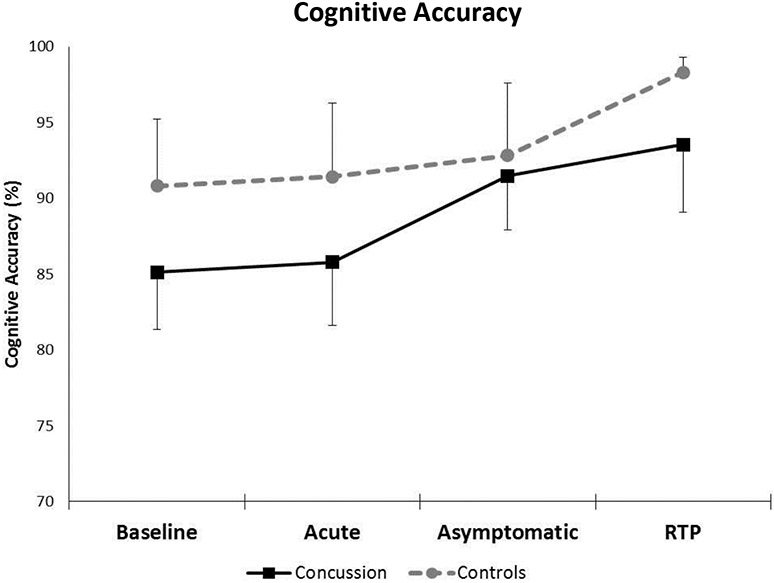

Cognitive Accuracy

There was not a significant group x time interaction (F=0.37, p=0.77) for cognitive accuracy during dual-task tandem gait. (Figure 3) There was a significant main effect for group (F=7.01, p=0.009) for cognitive accuracy during dual-task tandem gait. The concussion group (88.98%) had a worse (lower) cognitive accuracy than the controls (93.34%). There was also a significant main effect for time (F=4.90, p=0.002) whereby cognitive accuracy increased across time from Baseline to RTP in both the concussion and control groups.

Figure 3.

Cognitive accuracy (mean and 95% confidence interval bars) during dual-task tandem gait for the concussion and control groups across the clinical concussion milestones. The dual-task cognitive accuracy for both groups at each time point were as follows: Baseline (Concussion: 85.12% ± 14.95%, Controls: 90.82% ± 11.82%, p=0.08, Cohen’s d= 0.42), Acute (Concussion: 85.79% ± 15.09%, Controls: 91.41% ± 12.46%, p=0.11, Cohen’s d= 0.41), Asymptomatic (Concussion: 91.47% ± 12.61%, Controls: 92.81% ± 11.23%, p= 0.67, Cohen’s d= 0.11), and RTP (Concussion: 93.53% ± 14.24%, Controls: 98.30% ± 2.49%, p= 0.12, Cohen’s d= 0.47).

Within the concussion group, cognitive accuracy significantly improved from Baseline to Asymptomatic (6.35%, p=0.013) and Baseline to RTP (8.41%, p=0.002) but not from Baseline to Acute (0.67%, p=0.79). The control group only significantly improved their cognitive accuracy from Baseline to RTP (7.48%, p=0.04). Controls did not significantly improve their cognitive accuracy between Baseline and Acute (0.60%, p=0.87) or Baseline and Asymptomatic (2.00%, p=0.60).

Discussion

We evaluated single and dual-task tandem gait performance from preseason baseline testing through RTP following a concussion, relative to a group of uninjured controls. The SCAT-3 has included tandem gait as an alternative to the BESS for post-concussion postural control assessment; however, it has received limited attention, particularly in how performance changes throughout post-concussion recovery.3,6,8,20 The primary finding of this study was poorer (slower) single-task tandem gait performance in the concussion group at both the Acute and Asymptomatic time points. Furthermore, during dual-task tandem gait the concussion group had significantly poorer cognitive accuracy across all time points. These results support the use of tandem gait as a clinically feasible task that can be used as a post-concussion dynamic postural control measure.

During single-task tandem gait, the concussion group performed significantly worse (2.29 seconds, 22.4% slower) than controls within the acute post-concussion window, despite both groups being comparable at Baseline. Further, the concussion group’s performance exceeded the established minimum detectable change of 0.38 seconds6 for single-task tandem gait, demonstrating that the post-injury change was likely not due to scorer variability. The controls improved from Baseline to Acute while the concussion group’s performance worsened. Beyond the Acute time point, the concussion group means remained significantly greater than controls at Asymptomatic (1.06 seconds, 11.3% slower) but not at RTP (0.92 seconds, 10.1% slower). However, the concussion group mean at both the Asymptomatic and RTP time points was an improvement from Baseline; therefore, postural control impairments did not appear to linger throughout recovery. The concussion group failed to improve their tandem gait performance to the extent of the controls, however, since the concussion group remained slower despite returning to Baseline values. Our findings are consistent with others demonstrating that concussed individuals took longer to complete single-task tandem gait than healthy controls acutely following concussion.6,8 The inclusion of baseline data and post-concussion clinical milestones strengthens our knowledge of post-concussion tandem gait performance beyond acute post-injury performance. Of clinical importance is that the previous studies, as well as this investigation, observed an improvement in tandem gait performance across time in control populations, suggesting that tandem gait appears to be susceptible to a practice effect with repeat administration.6,8 However, this learning effect is clinically less critical than the same learning effect seen in the BESS, as tandem gait is objective compared to the subjective BESS scoring.

Similar to performance during single-task, both groups were similar at Baseline during dual-task tandem gait and diverged acutely post-concussion (Figure 2); however, the dual-task tandem gait interaction was not significant. The concussion group overall was 1.86 seconds greater (slower) than the healthy controls during timed dual-task tandem gait. Independent of group membership (concussion or control), dual-task tandem gait times were greatest at the Acute time point and continually improved across the Asymptomatic and RTP time points. Following the initial 48 hour window, the concussion group’s dual-task tandem gait times appeared to improve, as times at both Asymptomatic day and RTP were faster than Baseline. While change in motor performance is important, other factors may also be affected following concussion. Cognitive-motor interference occurs under dual-task conditions when the cognitive and/or motor tasks deteriorate compared to single-task performance.21 Therefore, it is important to evaluate both domains.

Cognitive accuracy in the concussion group appeared to improve from Baseline to Acute, so it is possible that the slower tandem gait times were a result of task prioritization, whereby the concussed individuals appeared to prioritize cognitive accuracy at the expense of motor performance. Conversely, the healthy controls appeared to improve on both cognitive accuracy and tandem gait time from Baseline to Acute. While the concussion group’s cognitive accuracy did slightly improve between the Baseline and Acute time points, the change was minimal and non-significant (0.67%, mean difference: −0.64, 95%CI: −4.99-3.72%). Impaired postural control secondary to a disruption of cortical pathways could alter the ability to control and coordinate movement, which could explain the slowed tandem gait acutely post-concussion.22,23 Further, working memory tasks require appropriate activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is impaired by a concussive injury based on neuroimaging.24-29 This theory has also been hypothesized as a potential underlying mechanism to the elevated musculoskeletal injury risk following concussion,22,30-32 and future research should explore tandem gait differences between those who do and do not sustain a subsequent injury.

While the underlying mechanism behind slower post-concussion tandem gait performance is unknown, it is possible that it could be due to the “goal oriented” nature of the task (i.e. completing the task as quickly as possible without stepping off the line.) Goal-directed locomotion is controlled by an indirect motor pathway that regulates movement via the prefrontal cortex, supplementary motor area, and basal ganglia, all of which are areas suggested to be adversely affected following concussion.24,25,33-36 Further, tandem gait has traditionally been considered a vestibular assessment; thus, it is possible that slower post-concussion times result from impaired vestibular function being exacerbated due to the spreading depression and energy crisis reported to occur after concussion.37 It is also possible that altered tandem gait performance may be related to an individual’s ability to control frontal plane movement.8 Moderate to high correlations (r=0.70-0.93) between frontal plane movement and mean tandem gait time have been identified, suggesting those who took longer to perform tandem gait displayed greater mediolateral center of mass displacement.8 Mediolateral balance impairments may reflect the inability to maintain gait stability during forward locomotion following a central nervous system injury, such as concussion. Furthermore, mediolateral balance alterations have been associated abnormal tandem gait among patients with Parkinson’s Disease, and while the fundamental neuropathologies of concussions and Parkinson’s are inherently different, it appears they might initially manifest in similar postural control impairments during tandem gait.38

Tandem gait impairments in neurologically impaired individuals have traditionally been determined as an inability to successfully perform the task (i.e. taking multiple steps off the designated line); however, as a concussion assessment, time has been used the primary outcome.6,8,20 As expected, we found slower tandem gait times during both single and dual-task acutely following concussion, which reinforces prior studies and suggests impaired postural control.6,8 Despite the slower performance, there were no instances where concussed collegiate student-athletes could not successfully complete the tandem gait task at any of the post-injury time points. This is clinically relevant, as the tandem gait guidelines have recently changed from the best of four timed trials in the SCAT-3 to a subjective “yes” or “no” response to whether or not an individual can perform tandem gait normally, which is not defined, in the SCAT-5.3,4 The tandem gait protocol for concussion has developed over the last decade, starting with Schneiders and colleagues evaluating the mean of three timed trials, and progressing to the SCAT-3 evaluating the best of four timed trials.3,9 Despite the lack of evidence-based guidelines for tandem gait procedure, there is a clinical need for a standardized protocol, which has been removed in the SCAT-5.4 Our results suggest that subjectively observing normal vs. abnormal tandem gait is not sensitive to post-concussion postural control impairments, even acutely post-concussion, as all participants successfully completed the task. Therefore, these results reinforce that time to complete tandem gait, an objective measure, should be included in clinical assessment.

This investigation focused solely on collegiate student-athletes, and generalizations to other populations (i.e. youth, high school) should not be made. Preliminary research in a high school population demonstrated that most athletes were unable to complete tandem gait in the 14 second cutoff suggested by the SCAT-3;5 however, future research is needed to examine post-concussion tandem gait performance changes and determine clinically meaningful completion times for that population. There was a significant difference between groups for the days between the Acute and Asymptomatic time points, as we were unable to predict the duration of injury-asymptomatic time among concussion group participants, and the testing interval between the Acute and Asymptomatic time points for controls was interrupted by a holiday break. However, we do not believe this influenced our results, as tandem gait has demonstrated high test-retest reliability in healthy individuals, and the controls were the group with the greater amount of time between test points.39 We did not exclude controls based on lower extremity injury history. Further, the controls recruited for this study were non-athlete controls, as it was challenging to recruit healthy student-athletes for multiple testing sessions. It should be a future priority to match concussed athletes to non-injured athletes as closely as possible. Although controlled for by the mixed model statistical approach, the amount of missing data across concussion time points was a limitation of this investigation; however, the missing data provides clinicians with a realistic approach to post-concussion recovery assessment, as there are any number of confounding factors (e.g. academic obligations, team commitments) that cause a student-athlete to miss follow-up time points.

Tandem gait is a clinically feasible, but underutilized, dynamic postural control assessment following concussion which may provide clinicians with more sensitive outcomes than the BESS test.6,8,40 Performance on single-task tandem gait was worse acutely post-concussion, compared to both baseline values and healthy controls. Beyond their preseason baseline, the concussion group remained slower than the healthy controls at the remaining testing time points; however, beyond the acute time frame, the concussed times continued to improve beyond those obtained at Baseline, which could be determined “recovered” by clinical standards. Therefore, tandem gait appears to be most valuable for identifying postural control impairments acutely post-concussion and less so across the remaining clinical milestones.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Financial Disclosures

Dr. Howell receives research support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (R03HD094560) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders And Stroke (R01NS100952 and R41NS103698) of the National Institutes of Health. He has previously received research support from a research contract between Boston Children’s Hospital, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and ElMindA Ltd, and the Eastern Athletic Trainers Association Inc. Dr. Buckley has received funding from the NIH/NINDS (R03NS104371) and the NCAA/DoD CARE Consortium (W81XWH-14-2-0151). For the remaining authors none were declared.

This study was approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion ins sport-the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sport Med. 2017;51:838–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckley T, Oldham J, Caccese J. Postural control deficits identify lingering post-concussion neurological deficits. J Sport Heal Sci. 2016;5:61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SCAT3. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, et al. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition (SCAT5). Br J Sport Med. 2017;51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santo A, Lynall R, Guskiewicz K, et al. Clinical utility of the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 3 (SCAT3) tandem-gait test in high school athletes. J Athl Train. 2017;52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oldham JR, Difabio MS, Kaminski TW, et al. Efficacy of Tandem Gait to Identify Impaired Postural Control after Concussion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50. Doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howell D, Wilson J, Brilliant A, et al. Objective clinical tests of dual-task dynamic postural control in youth athletes with concussion. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;Epub ahead. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell D, Osternig L, Chou L. Single-task and dual-task tandem gait test performance after concussion. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20:622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneiders AG, Sullivan SJ, Gray AR, et al. Normative values for three clinical measures of motor performance used in the neurological assessment of sports concussion. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13:196–201. Doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stolze H, Klebe S, Petersen G, et al. Typical features of cerebellar ataxic gait. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:310–312. Doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.3.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kammerlind A, Larsson P, Ledin T, et al. Reliability of clinical balance tests and subjective ratings in dizziness and disequilibrium. Adv Physiother. 2005;7:96–107. Doi: 10.1080/14038190510010403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott MH. Normal Postural Control. 4th Editio: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2012: 161–162. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCrea M, Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, et al. Acute effects and recovery time following concussion in collegiate football players: the NCAA concussion study. JAMA. 2003;290:2556–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell D, Osternig L, Chou L. Dual-task effect on gait balance control in adolescents with concussion. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:1513–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howell DR, Osternig LR, Chou L-S. Adolescents Demonstrate Greater Gait Balance Control Deficits After Concussion Than Young Adults. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howell D, Osternig L, Chou L. Return to Activity after Concussion Affects Dual-Task Gait Balance Control Recovery. vol. 47. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell D, Oldham J, Meehan W, et al. Dual-Task Tandem Gait and Average Walking Speed in Healthy Collegiate Athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert F, Burdette G, Joyner A. Association between concussion and lower extremity injuries in collegiate athletes. Sports Health. 2016;8:561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell DR, Osternig LR, Koester MC, et al. The effect of cognitive task complexity on gait stability in adolescents following concussion. Exp Brain Res. 2014;232:1773–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oldham JR, DiFabio MS, Kaminski TW, et al. Normative Tandem Gait in Collegiate Student-Athletes: Implications for Clinical Concussion Assessment. Sports Health. 2017;9. Doi: 10.1177/1941738116680999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abenethy B Dual-task methodology and motor skills research: some applications and methodological constraints. J Hum Mov Stud. 1988;14:101–132. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynall RC, Mauntel TC, Padua D a., et al. Acute Lower Extremity Injury Rates Increase following Concussion in College Athletes. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2015:1. Doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pietrosimone B, Golightly Y, Mihalik J, et al. Concussion frequency associates with musculoskeletal injury in retired NFL players. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2015;11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slobounov S, Sebastianelli W, Moss R. Alteration of posture-related cortical potentials in mild traumatic brain injury. Neurosci Lett. 2005;383:251–255. Doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamacher D, Herold F, Wiegel P, et al. Brain activity during walking: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;57:310–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanctis P, Butler J, Malcolm B, et al. Recalibration of inhibitory control systems during walking-related dual-task interference: A Mobile Brain-Body Imaging (MOBI) study. Neuroimage. 2014;94C:55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holtzer R, Mahoney J, Izzetoglu M, et al. fNIRS study of walking and walking while talking in young and old individuals. J Gerontol. 2011;66A:879–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atsumori H, Kiguchi M, Katura T, et al. Noninvasive imaging of prefrontal activation during attention-demanding tasks performed while walking using a wearable optical topography system. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Johnston K, Frey S, et al. Functional abnormalities in symptomatic concussed athletes: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2004;22:68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howell D, Lynall R, Buckley T, et al. Neuromuscular control deficits and the risk of subsequent injury after a concussion: a scoping review. Sport Med. 2018;EPub ahead. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fino P, Becker L, Fino N, et al. Effects of recent concussion and injury history on instantaneous relative risk of lower extremity injury in Division I collegiate athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2017;EPub ahead. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pietrosimone B, Golightly YM, Mihalik JP, et al. Concussion Frequency Associates with Musculoskeletal Injury in Retired NFL Players. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2015. Doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jantzen K, Anderson B, Steinberg F, et al. A prospective functional MR imaging study of mild traumatic brain injury in college football players. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:738–745. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J, Johnston K, Petrides M, et al. Neural substrates of symptoms of depression following concussion in male athletes with persisting postconcussion symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zwergal A, Linn J, Xiong G, et al. Aging of human supraspinal locomotor and postural control in fMRI. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1073–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.La Fougere C, Zwergal A, Rominger A, et al. Real versus imagined locomotion: a F-FDG PET-fMRI comparison. 2010. n.d.;50:1589–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giza CC, Hovda DA. The Neurometabolic Cascade of Concussion. J Athl Train. 2001;36:228–235. Doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Margolesky J, Singer C. How tandem gait stumbled into the neurological exam: a review. Neurol Sci. 2018;39:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howell D, Brilliant A, Meehan III W. Tandem Gait Test-Retest Reliability Among Healthy Child and Adolescent Athletes. J Athl Train. 2019;54:Online Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buckley T, Burdette G, Kelly K. Concussion-Management Practice Patterns of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division II and III Athletic Trainers: How the Other Half Lives. J Athl Train. 2015;50:879–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]