Abstract

Nanozyme is a type of nanomaterial with intrinsic enzyme-like activity. Following the discovery of nanozymes in 2007, nanozyme technology has become an emerging field bridging nanotechnology and biology, attracting research from multi-disciplinary areas focused on the design and synthesis of catalytically active nanozymes. However, various types of enzymes can be mimicked by nanomaterials, and our current understanding of nanozymes as enzyme inhibitors is limited. Here, we provide a brief overview of the utility of nanozymes as inhibitors of enzymes, such as R-chymotrypsin (ChT), β-galactosidase (β-Gal), β-lactamase, and mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase, and the mechanisms underlying inhibitory activity. The advantages, challenges and future research directions of nanozymes as enzyme inhibitors for biomedical research are further discussed.

Keywords: nanozyme, R-chymotrypsin inhibitor, β-galactosidase inhibitor, β-lactamase inhibitor, mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase inhibitor

Introduction

In the early 1960s, the Japanese scientist Umezawa put forward the concept of “enzyme inhibitor”, a compound that specifically acts on certain groups of the enzyme, thereby affecting the active center and leading to a decline in the rate of enzymatic reaction.1 Enzyme inhibitors have been shown to play important roles in various biomedical and clinical areas, from biometrics to treatment of numerous diseases including diabetes,2 emphysema,3 Alzheimer’s disease,4 and even cancer.5 Although the existence of enzyme inhibitors in organisms is as widespread as enzymes, less than 10% plant species have been tested for any type of biological activity. At present, enzyme inhibitors are mainly derived from plants, microorganisms and chemical synthesis.6 However, screening for plant- or microorganism-derived enzyme inhibitors often produces a large number of “false-positive” results, which interferes with the identification of true active components7 and enzyme inhibitors obtained through chemical synthesis inevitably display highly selective inhibitory activity on one or a few types of enzymes.8,9 Moreover, high concentrations of small-molecule inhibitors are usually required to maintain their bioactivities, inevitably resulting in non-targeted effects and toxicity.10 Therefore, development of inhibitors with a broad spectrum of activity remains a hot topic for future research.

Nanozymes are a class of nanomaterials with intrinsic enzyme-mimicking characteristics, mainly including peroxidase-, oxidase-, catalase-, and superoxide dismutase-like activities.11 Compared with natural enzymes, nanozymes are more stable at a wider range of pH and temperatures in addition to several advantages, such as low cost, high stability and easy large-scale preparation.12 The multi-enzyme activities of nanozymes have been successfully applied in numerous fields, such as biosensor development, cancer treatment, environmental protection, and antimicrobial therapy.13–16 Unexpectedly, in addition to their biocatalytic functions, nanozymes have been shown to selectively bind different enzymes and inhibit their activities, further extending their potential biomedical applications.

In this review, we have focused on the nanomaterials that worked as both nanozymes and enzyme inhibitors, and discussed their properties, inhibitory mechanisms, and novel applications. The current status and future perspectives are summarized, with the aim of providing novel insights that could aid in improving the design of new enzyme inhibitors and better understanding the biological activities of nanozymes.

Nanozymes as R-Chymotrypsin Inhibitors

R-chymotrypsin (ChT) was first identified as a structured serine protease by Blow.1 Among the multiple known serine proteases, ChT is considered an excellent system for exploring protein surface recognition to achieve direct inhibition of active sites due to its geometry and extensive enzymatic properties.17 In this regard, small-molecule inhibitors, such as porphyrin derivatives and cyclodextrin dimers, have been recently designed as receptors for the interaction domain of the protein periphery surface to regulate enzyme behavior.18,19 More recently, nanomaterials have attracted significant attention as suitable and promising candidates to achieve protein surface recognition owing to two unique properties not displayed by small-molecule inhibitors: 1) large receptor surface areas that promote efficient protein surface contact and binding and 2) easy fabrication to provide useful and functionalized structures.20

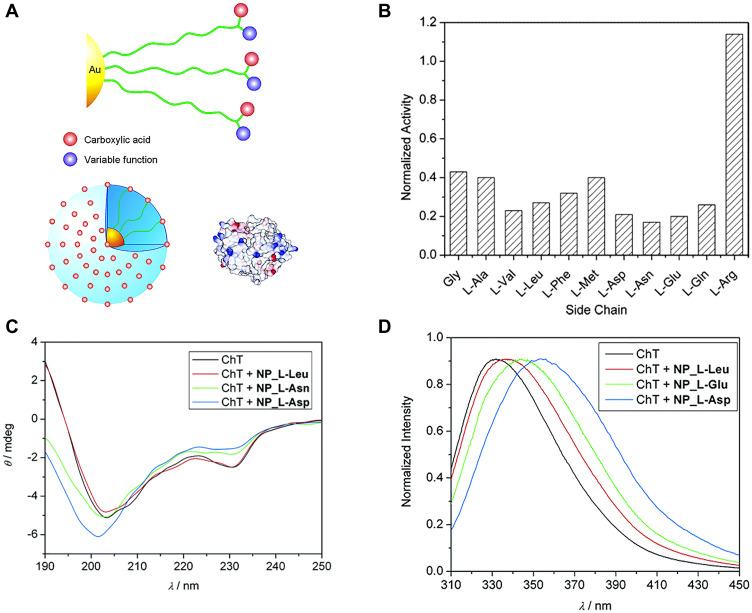

To obtain functional nanomaterials similar to protein surfaces, You et al21 constructed carboxylic acid-functionalized gold nanoparticles with different L-amino acids (Figure 1A) and investigated their effects on the rate of ChT-catalyzed N-succinyl-L-alanine-p-nitroanilide (SPNA) hydrolysis. Gold nanoparticles are known to possess peroxidase-, oxidase-, and glucose oxidase-like activities.22 In the presence of negatively charged amino acid-modified gold nanoparticles, such as NP_Gly, NP_L-Gln, NP_L-Asn, NP_L-Glu, NP_L-Asp, NP_L-Phe, NP_L-Leu, NP_L-Met, NP_L-Val, and NP_L-Ala, the rate of ChT-catalyzed SPNA hydrolysis was reduced, supporting a significant inhibitory effect on ChT activity. In contrast, gold nanoparticles modified with positively charged amino acids (NP_L-Arg) exerted no obvious effects on ChT activity (Figure 1B). These results indicate that complementary electrostatic interactions between nanoparticles and ChT provide the main driving force for the formation of high-affinity complexes. The ChT active site is surrounded by cationic residues, which favorably bind negatively charged gold nanoparticles. More importantly, in a study on structural stability of proteins, the circular dichroism (CD) spectrum of ChT was completely dependent on the amino acid side-chains of nanoparticles. In the presence of gold particles with a hydrophobic amino acid side-chain, NP-L-Leu, almost no changes in the CD spectrum of ChT were observed, while nanoparticles with hydrophilic L-Asn and L-Asp side-chains induced varying degrees of CD spectral changes (Figure 1C). To understand the denaturation kinetics of ChT in the presence of nanoparticles, a more sensitive steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy method was used to analyze the characteristic fluorescence of tryptophan residues in ChT. The degree of denaturation of ChT is reflected by differences in fluorescence shift values. Notably, after incubation with nanoparticles for 24 h, hydrophilic NP_L-Asp induced about 90% ChT denaturation while hydrophobic NP_L-Leu only induced 20% denaturation (Figure 1D). A reasonable explanation for this finding is that the side-chains of hydrophobic amino acids only interacted with hydrophobic plaques on the ChT surface, preserving the protein structure in the same way as natural protein-protein interactions, while hydrophilic L-Asn and L-Asp induced ChT degeneration by competing for hydrogen bonds or destroying salt bridges. It suggested that the carboxylate function facilitated the denaturation process, and the formation of competitive hydrogen bonding might destabilize the α-helices in ChT and disrupt their secondary structure. Thus, the surface properties of nanomaterials play a key role in controlling the regulation of ChT association/dissociation/stability/denaturation. To further improve the versatility of surface receptors, it is possible to introduce extra ligand functionality, such as carboxylic acid recognition elements, to nanoparticle interfaces.

Figure 1.

(A) Amino acid-decorated cluster surface that consists of carboxylic acid recognition elements as well as extra functions for perturbation. The relative sizes of amino acid-functionalized gold nanoparticles and ChT. The surface of ChT is patterned with the electrostatic surface potential, showing basic and acidic domains on protein surface. (B) Normalized activity of ChT with nanoparticles bearing various amino acid side chains. (C) Circular dichroism spectra of ChT and ChT with nanoparticles after 24 h incubation. The weak CD signal of the nanoparticles has been subtracted from that of the complex. (D) Fluorescence spectra of ChT and ChT with nanoparticles after 24 h incubation. Reprinted with permission from You CC, De M, Han G et al Tunable inhibition and denaturation of α-Chymotrypsin with amino acid-functionalized gold nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(37):12873–12881. Copyright (2005) American Chemical Society.21

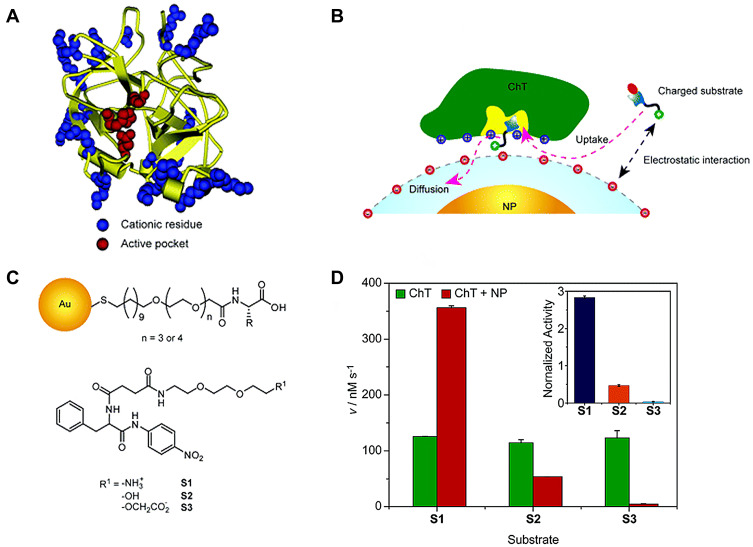

ChT, a representative serine protease, displays a characteristic structure. As shown in Figure 2A, the active site is surrounded by a positively charged residue loop while some hydrophobic “hot spots” are distributed on the surface. Owing to this structural feature, electrostatic interactions play an important role in enzyme-substrate binding (Figure 2B). Studies by You et al23 demonstrated that amino acid (carboxylic acid group)-functionalized gold nanoparticles form supramolecular complexes with ChT (ChT-nanoparticle complexes) that display different enzymatic kinetics for three SPNA-derived substrates with diverse charge characteristics (cationic SPNA (S1), neutral SPNA (S2) and anionic SPNA (S3); Figure 2C). After the formation of ChT-nanoparticle complexes, the substrate-binding ability of ChT depends on electrostatic interactions between the amino acid monolayer and various substrates. In this case, the SPNA hydrolysis rate was in the order S1>S2>S3. Compared with S1, the specificity constant of ChT for S3 was significantly decreased due to the strongest electrostatic repulsion between the monolayer and substrate (Figure 2D). These results indicate that the amino acid-functionalized gold nanoparticles as nanoreceptors regulate rather than simply inhibit ChT activity. The inhibitory activity of nanoparticles on enzymes is distinct from traditional competitive and non-competitive mechanisms,24 which is not only for the preparation of enzyme regulators based on surface recognition provides an effective scaffold, but also has broad application prospects in protein stability, modification and delivery.

Figure 2.

(A) Molecular structure of R-chymotrypsin. (B) Schematic representation of monolayer-controlled diffusion of the substrate into and the product away from the active pocket of nanoparticle bound ChT. (C) Chemical structure of amino-acid-functionalized gold nanoparticles and SPNA-derived substrates. (D) Generation rate (V) of 4-nitroaniline from different substrates under catalysis by ChT or ChT-nanoparticle complex. Inset shows the normalized activity of ChT-NP complex to ChT toward different substrates. Reprinted with permission from You CC, Agasti SS, De M et al Modulation of the catalytic behavior of α-Chymotrypsin at monolayer-protected nanoparticle surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(45):14612–14618. Copyright (2006) American Chemical Society.23

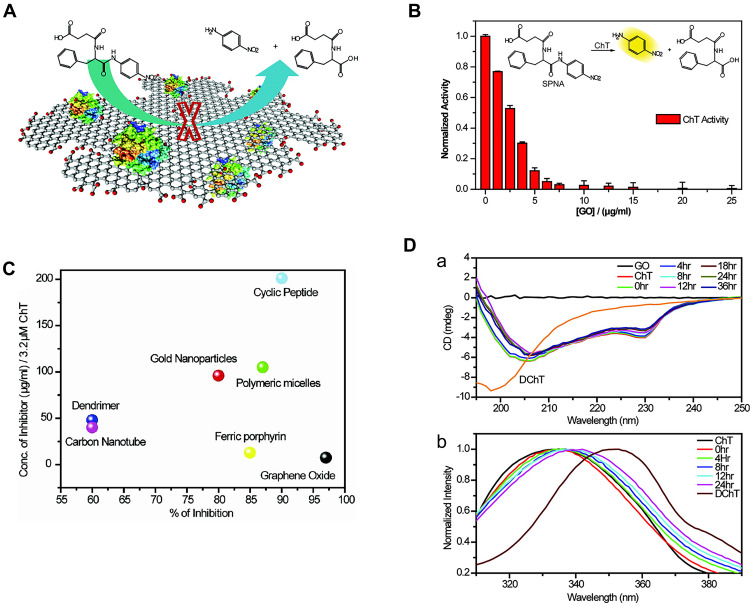

Graphene oxide (GO) has been reported as a nanozyme possessing peroxidase-like activity.25 Furthermore, GO can act as an artificial ChT inhibitor due to unique properties, such as surface functionality, large surface area to mass ratio, and flexibility. De et al26 introduced carboxylate groups into native GO, which bound the cationic surface residues of ChT and simultaneously inhibited catalytic behavior towards anionic substrates (Figure 3A). Further evaluation of the effect of GO on ChT revealed that complete inhibition was achieved at a GO concentration of 20 μg/mL (Figure 3B). Compared with other reported artificial ChT inhibitors, GO exerted the highest inhibitory effect (Figure 3C). More importantly, receptor interaction was highly biocompatible and the secondary structure of the protein maintained for a longer time period, as evident from fluorescence and CD spectra (Figure 3D). This high efficiency was attributed to the flexibility of the monolayer of GO, which facilitated adaptation to the surface curvature of the protein. The GO monolayer membrane could bind in a firm and compatible manner to the ChT surface, and the presence of hydrophobic aromatic groups in GO enhanced its affinity to hydrophobic “hot spots” around the active sites of ChT. Therefore, modification of GO with various active biomolecules could expand its biological applicability as an effective inhibitor with higher specificity and selectivity.27

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic diagram of GO inhibition ChT principle. (B) Activity of ChT plotted as a function of GO concentration in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) using SPNA as a substrate. The activities were normalized to that of ChT. (C) Degrees of inhibition and relative concentrations of various inhibitors used for altering the ChT activity. The right-bottom corner represents the most efficient inhibitor. (D(a)) CD spectra and (b) Tryptophan fluorescence of ChT with GO at different times. Reprinted with permission from De M, Chou SS, Dravid VP. Graphene oxide as an enzyme inhibitor: Modulation of activity of α-Chymotrypsin. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(44):17524–17527. Copyright (2011) American Chemical Society.26

Nanozymes as β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) Inhibitors

Similar to ChT, β-galactosidase (β-Gal) is a typical proteolytic enzyme that plays a crucial role in catalyzing hydrolysis of lactose to galactose.28 Upregulation of β-Gal is usually related to the occurrence of primary ovarian cancer and cell aging, and β-Gal inhibitors have been developed for application in clinical diagnosis of a number of diseases.29

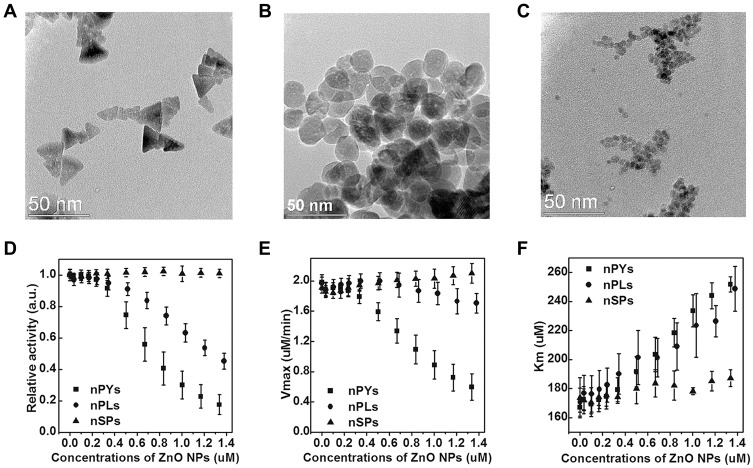

Given the diversity of enzyme inhibitors, the development of novel nanoparticle inhibitors with unconventional structures has become a focus of research direction in recent years.30 The biocatalytic inhibitory activities of these new inhibitor types strongly depend on shape effects due to their diverse geometries. Earlier reports have shown that ZnO NPs with peroxidase activity have potential shape regulation capacity.31 Cha and co-workers fabricated three types of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NP) with different geometries by altering the shape and surface chemistry, including hexagonal nanopyramids, nanoplates and nanospheres (Figure 4A–C), and systematically compared the inhibitory effects of the different ZnO NPs on catalytic capacity of β-Gal. Their results showed that enzyme activity gradually decreased with increasing concentrations of nanopyramids and nanoplates but remained unchanged for all concentrations of nanospheres (Figure 4D–F). Moreover, relative to nanoplates, sharper apexes and edges of ZnO nanopyramids resulted in a higher degree of geometrical matching with the enzyme surface around the active center, thus inducing the strongest inhibitory effects. Therefore, in addition to hydrogen bonding and Vender Waals forces, molecular shape-dependent inhibitory behavior is responsible for weakening of the binding affinity of the substrate to the active site.

Figure 4.

TEM images of ZnO (A) nanopyramids (nPYs), (B) nanoplates (nPLs), and (C) nanospheres (nSPs). (D) Relative catalytic activity of GAL in the presence of three different shaped ZnO NPs after 60 min incubation time. Each relative catalytic activity of GAL with ZnO NPs was normalized with respect to free enzyme activity. The values for (E) Vmax and (F) Km of GAL were calculated from the Michaelis-Menten equation. Reprinted with permission from Cha SH, Hong J, McGuffie M et al Shape-dependent biomimetic inhibition of enzyme by nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity. ACS Nano. 2015;9(9):9097–9105. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acsnano.5b03247.30

Nanozymes as β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) and R-Chymotrypsin (ChT) Inhibitors

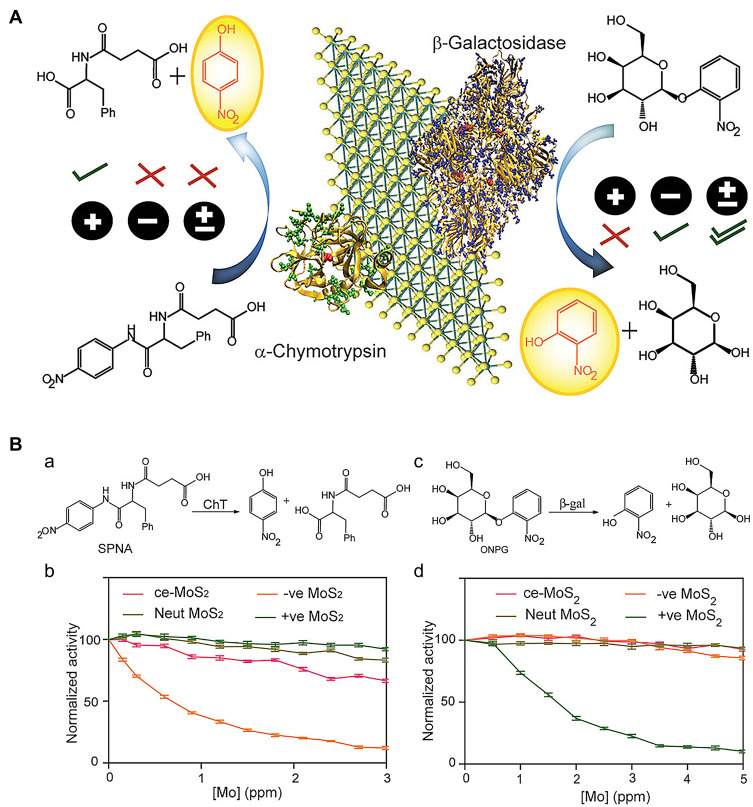

Unlike various traditional small-molecule inhibitors that target active sites, nanomaterials are more likely to act as broad-spectrum inhibitors due to their unique inhibitory mechanisms and biocompatibility. As a typical transition metal dichalcogenide, MoS2 has the ability to mimic peroxidase.32 Earlier, Karunakaran et al33 demonstrated that MoS2, after surface modification through facile thiol chemistry, could simultaneously inhibit β-Gal and ChT activity (Figure 5A). ChT contains positively charged residues around the active site that combine with negatively charged macromolecules, resulting in inhibition of enzymatic activity. Negative ligand-conjugated MoS2 exhibited high inhibitory activity for ChT (up to 90%) at a concentration of 3 μg/mL. Conversely, positive MoS2 exerted limited inhibitory effects on ChT activity (Figure 5B (a) and 5B (b)). In addition, positively charged MoS2 at a concentration of 4 μg/mL interacted with negatively charged β-Gal through electrostatic interactions to significantly inhibit activity (~90%) of the enzyme (Figure 5B). In contrast, neutral ligand-conjugated MoS2 exerted no significant inhibitory effects on both enzymes, even at high concentrations (Figure 5B (c) and 5B (d)).

Figure 5.

(A) Functionalized MoS2 interactions with different charges and different proteins. (B(a and b)) Enzymatic activity of ChT as a function of inhibitor concentrations in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) using SPNA as a substrate. The activities were normalized to that of only ChT. (c and d) Enzymatic activity of β-Gal as a function of the same inhibitor concentrations in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) using o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside as a substrate. The activities were normalized to that of only β-gal. Reprinted with permission from Karunakaran S, Pandit S, De M. Functionalized two-dimensional MoS2 with tunable charges for selective enzyme inhibition. ACS Omega. 2018;3(12):17532–17539. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.8b02598.33

Nanozyme as β-Lactamase Inhibitors

The discovery of penicillin in 1929 is considered a milestone in the history of medicine.34 Penicillin was successfully used as clinical treatment for bacterial infections in the 1940s. However, within a few years of using penicillin therapy, several bacterial strains began to exhibit antibiotic resistance through natural production of penicillinase. Penicillinase, also known as β-lactamase, can destroy the β-lactam ring structure of penicillin to inactivate drugs.35 Therefore, β-lactamase-controlled drug resistance poses a serious threat to the widespread clinical application of antibiotics. In this situation, development of appropriate β-lactamase inhibitors presents one of the most crucial strategies to combat multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. To date, various small-molecule inhibitors with similar structures to penicillin have been designed, such as clavulanic acid, sulbactam and tazobactam.36 However, almost all these inhibitors contain a lactam ring and cannot be used as general inhibitors due to distinct inactivation mechanisms for different types of β-lactamases. Nanomaterials have many advantages over small-molecule inhibitors as potential β-lactamases inhibitors, such as large surface area and surface functional modification, which significantly alter enzyme activity through multivalent interactions or steric hindrance, and display enhanced efficacy in combination with various β-lactamases.

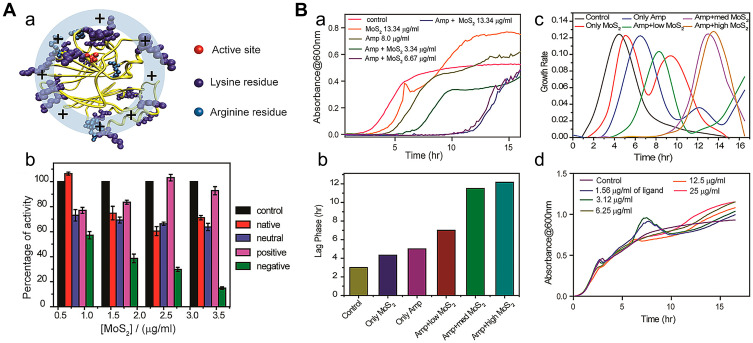

Pandit et al37 synthesized several functionalized two-dimensional molybdenum disulfide (2D-MoS2) nanomaterials as enzyme inhibitors. The group showed that carboxylate-functionalized negatively charged MoS2 is a potent inhibitor that effectively blocks the active site of β-lactamase and exhibits competitive inhibitory activity. The mechanism of inhibition was structurally attributed to the active center of β-lactamase being surrounded by cationic (lysine and arginine) residues (Figure 6Aa). Moreover, electrostatic interactions and steric blockage between enzymes and inhibitors additionally played an important role (Figure 6Ab). Combined antibacterial effects against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) using MoS2 as a β-lactamase inhibitor and ampicillin as an antibiotic were additionally evaluated. The results showed that under conditions of co-treatment of ampicillin and MoS2, growth of MRSA was inhibited with a delay in the bacterial growth rate in an MoS2 dose-dependent manner (Figure 6Ba and b), indicating that in the presence of the β-lactamase inhibitor, MoS2, destruction of the antibiotic agent, ampicillin, by the MRSA bacterial strain could be prevented, resulting in delayed bacterial growth. However, in the presence of negative functionalized MoS2 only, bacterial growth was not significantly disrupted (Figure 6Bc), even at a very high concentration (25 μg/mL; Figure 6Bd), suggesting that MoS2 with negative ligands does not inhibit bacterial growth and is not toxic to microorganisms. This strategy combines the unique mechanisms and controllable biological activity of nanomaterials as enzyme inhibitors, providing a novel solution for clinical antibiotic resistance. Functionalized nanomaterials were more effective as combination therapy in antibacterial tests of MRSA in vitro, suggesting that enhanced inhibitory effects could be achieved by adjusting the nanomaterial surface.

Figure 6.

(A(a)) Structure of β-lactamase. The active site (red) of β-lactamase is surrounded by lysine and arginine (blue) residues. (b) Activity of β-lactamase in the presence of increasing concentration of various 2D MoS2 in HEPES buffer (pH 7.3) using nitrocefin as a substrate. (B) Growth curve analysis for the bacterial strain MRSA, treated with ampicillin with various concentrations of negative functionalized MoS2 at 37°C. (a) The bacterial growth curves over a period of 16 h, in a real-time kinetic cycle. (b) The lag phase diagram and (c) first derivative growth rate for quantitative analysis of the growth curve. (d) Growth curve analysis for the bacterial strain MRSA, treated with various concentrations of negative ligand molecule at 37°C over a period of 16 h, in a real-time kinetic cycle. Reprinted with permission from Ali SR, Pandit S, De M. 2D-MoS2-Based β-Lactamase Inhibitor for combination therapy against drug-resistant bacteria. ACS Applied Bio Materials. 2018;1(4):967–974. Copyright (2018) American Chemical Society.37

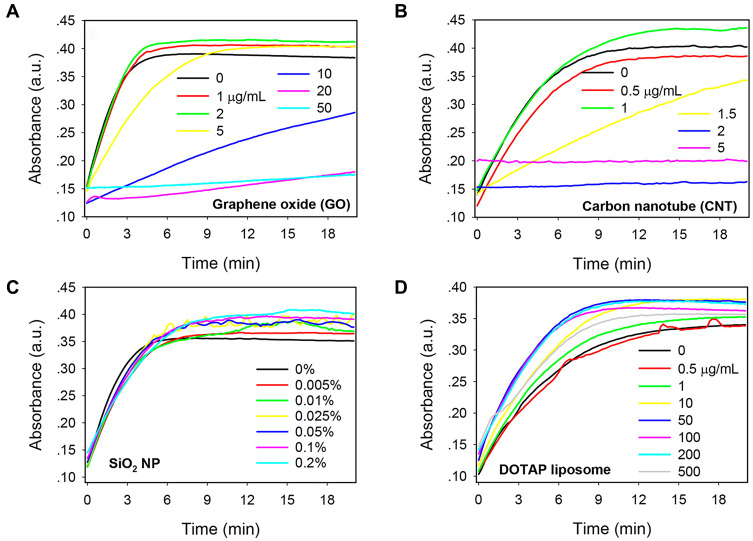

Metallo-β-lactamases (MBL) represent one of the β-lactamase types that hydrolyze a broad spectrum of β-lactam antibiotics. Currently, no inhibitors that can effectively suppress enzyme hydrolysis activity are available in the clinic.38 Verona integron-encoded-2 (VIM-2), a subclass of MBLs, is a negatively charged protein with Zn2+-dependent enzyme activity.39 In a systematic investigation by Huang and co-workers,40 the effects of various nanomaterials on VIM-2 catalytic activity were explored. Among the ten nanomaterials examined with different surface properties, graphene oxide (GO) and carbon nanotube (CNT) exerted significant inhibitory effects on VIM-2 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 7A and B). Interestingly, this strong suppression effect contributed to hydrophobic interactions between VIM-2 and nanomaterials, but not electrostatic interactions (Figure 7C and D). Similar to VIM-2, both GO and CNT possess hydrophobic regions that may play a key role in disrupting enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Additionally, CNT exerted a more significant inhibitory effect at lower concentrations than GO. Owing to its smaller diameter, CNT fits more efficiently into the enzyme hydrophobic core. Distinct from the competitive inhibitory mechanisms of nanomaterials against ChT, GO exhibited strong non-competitive inhibition activity without inducing changes to the enzyme structure.

Figure 7.

Kinetics of nitrocefin color change induced by VIM-2 in the presence of various concentrations of nanomaterials: (A) GO, (B) CNT, (C) 50 nm SiO2 NPs, and (D) cationic DOTAP liposomes. Reprinted with permission from Huang PJJ, Pautler R, Shanmugaraj J et al Inhibiting the VIM-2 metallo-β-lactamase by graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2015;7(18):9898–9903. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acsami.5b01954.40

Nanozyme as Mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase Inhibitors

F0F1-ATPase, also known as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase, participates in the synthesis of ATP to meet the high energy requirements of cells.41 ATP synthase is composed of F0-ATP synthase and F1-ATP synthase subunits.42 H+ proton flux through the F0-ATP synthase subunit drives the mechanical rotation of the γ and ε subunits within F1-ATP synthase, leading to synchronized conformational changes and production of ATP with high kinetic efficiency.43,44 Under pathological conditions (ie, hypoxia), the F0-ATP synthase subunit paradoxically hydrolyses ATP, which is responsible for causing mitochondrial dysfunction linked to cell death.45–47 Therefore, inhibition of F0-ATP hydrolase catalytic activity plays an essential role in maintaining normal cellular metabolism, especially in conditions where mitochondrial ATP hydrolysis is exacerbated.

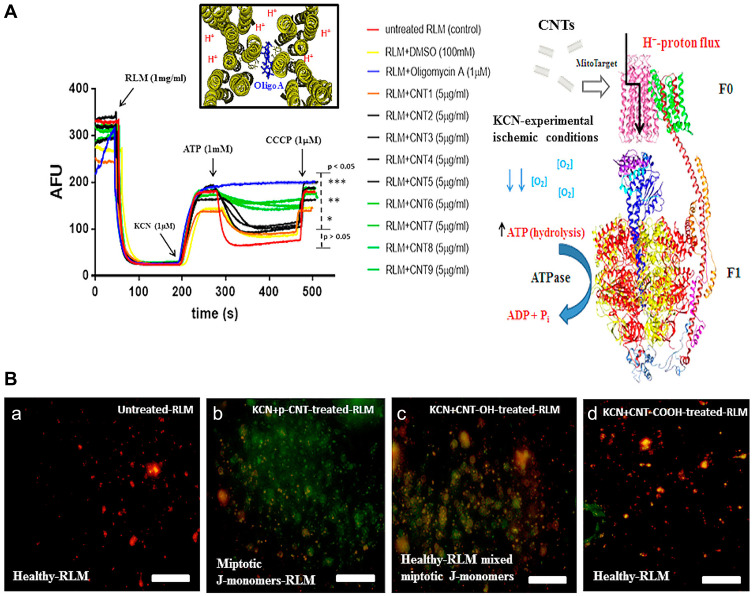

Carbon nanotubes (CNT) are one of most widely characterized nanomaterials with high biocompatibility and high selectivity for subcellular components, in particular, mitochondria.48,49 Michael and co-workers50 examined the potential of oxidized CNT family members to induce inhibition of mitochondrial F0-ATP hydrolase toxicity. Compared to pristine multi-walled carbon nanotubes (CNT-1) that displayed no inhibitory activity, oxidized CNT family members (CNT2-9) markedly suppressed F0-ATP hydrolase activity at a concentration of 5 µg/mL. Deprotonated oxidized moieties, such as CNT-O- and CNT-COO-, could interact electrostatically with H+ protons, preventing H+ proton flux through F0-ATP synthase and subsequent rotation of the γ and ε subunits of F1-ATP synthase (Figure 8A). Notably, toxicological inhibition of F0-ATP hydrolase induced no effects on mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) (Figure 8B). The collective findings should promote further rational design of carbon nanomaterial structures to fulfill novel applications based on toxicological regulation and provide new opportunities for emerging research fields, such as mitochondrial nanotoxicology.

Figure 8.

(A) H+-F0-ATPase save for the pristine multi-walled carbon nanotube (CNT-1) that show low ability to induce F0-ATPase nanotoxicity-based inhibition in isolated rat liver mitochondria. (B) ATP-hydrolysis inhibition by CNT-family members at maximum concentration of 5µg/mL in isolated-rat liver mitochondria (RLM). (a) Untreated-RLM (J-aggregates: red fluorescence); (b) KCN+p-CNT-treated-RLM (miptotic J-monomers: green fluorescence); (c) KCN+CNT-OH (CNT2-CNT5) treated-RLM (J-aggregates mixed miptotic J-monomers: red to pseudo-colored red fluorescence); (d) KCN+CNT-COOH (CNT6-CNT9) treated-RLM (J-aggregates: red fluorescence). Reprinted with permission from González-Durruthy M, Manske Nunes S, Ventura-Lima J et al Mitotarget modeling using ANN-classification models based on fractal SEM nano-descriptors: Carbon nanotubes as mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase inhibitors. J Chem Inf Model. 2019;59(1):86–97. Copyright (2018) American Chemical Society.50

Discussion

In this report, achievements in the application of various nanomaterial-based enzyme inhibitors in recent years have been comprehensively reviewed. It is worth emphasizing that these nanomaterials possess the ability serving as both nanozymes and enzyme inhibitors (Table 1). The versatility of nanozymes has significant prospects in the field of biomedicine. However, considerable challenges remain in terms of exploring the infinite potential of nanozymes as enzyme inhibitors due to a number of reasons. (1) Most nanozyme-based inhibitors lack the specific recognition capability of traditional small-molecule inhibitors and are therefore unlikely to act selectively through electrostatic or hydrophobic interactions. Once the surface of nanomaterials is blocked by other proteins, their activity as inhibitors of target enzymes is markedly reduced. (2) A considerable number of targets exist mainly in the form of intracellular enzymes (although they can also be released into the surrounding medium) and in order to effectively inhibit enzyme activity, nanomaterials need to cross the cell membrane, which is a key challenge in the development of effective enzyme inhibitors. (3) The long-term safety of nanomaterials remains to be ascertained. Further studies focused on optimizing and improving the structures of nanozymes are therefore warranted to improve their specificity and explore potential novel applications.

Table 1.

Summary of Nanozymes as Both Enzymes and Enzyme Inhibitors

| Nanozymes | As Enzyme Mimics | As Enzyme Inhibitors | Inhibition Mechanism | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au NPs21,23 | Peroxidase-, oxidase-, and glucose oxidase-like activities | ChT | Electrostatic interactions | Protein interaction |

| GO26 | Peroxidase-like activity | ChT | Hydrophobic interaction | Protein surface recognition |

| ZnO NPs30 | β-Gal | Hydrogen bonding, Vender Waals force, Molecular shape | Occurrence of primary ovarian cancer and cell aging | |

| MoS233 | β-Gal and ChT | Electrostatic interactions | Disease diagnosis and treatment | |

| 2D-MoS237 | β-lactamase | Electrostatic interactions and steric blockage | β-lactamase antibiotic resistance | |

| GO and CNT40 | MBLs | Hydrophobic interaction | Inhibit the hydrolysis of broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotics | |

| CNTs50 | F0F1-ATPase | Electrostatic interactions | Mitochondrial dysfunction |

Abbreviations: AuNPs, gold nanoparticles; GO, graphene oxide; ZnO NPs, ZnO nanoparticles; CNTs, carbon nanotubes; ChT, R-chymotrypsin; β-Gal, β-galactosidase; MBLs, metallo-β-lactamases.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21703198). The authors also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and High-Level Talent Support Plan of Yangzhou University.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Blow DM. Structure and mechanism of chymotrypsin. Accounts Chem Res. 1976;9(4):145–152. doi: 10.1021/ar50100a004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun SJ, Chen YT, Liu Q, et al. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor for the treatment of diabetes. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:306. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guarnieri F, Spencer JL, Lucey EC, et al. A human surfactant peptide-elastase inhibitor construct as a treatment for emphysema. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(23):10661–10666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001349107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunet C, Jegaden M, Darque A, et al. Anticholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a cohort since 1994. Pharm World Sci. 2009;31(2):272–273. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorai T, Aggarwal BB. Role of chemopreventive agents in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2004;215(2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujimoto T, Matsushita Y, Gouda H, et al. In silico multi-filter screening approaches for developing novel beta-secretase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18(9):2771–2775. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Kwon SH, Hwang SH, et al. Competitive binding experiments can reduce the false positive results of affinity-based ultrafiltration-HPLC: a case study for identification of potent xanthine oxidase inhibitors from Perilla frutescens extract. J Chromatogr B. 2017;1048:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parish EJ, Honda H, Lo YC, et al. New approaches to the chemical synthesis of citronellol type compounds useful as enzyme inhibitors. Abstr Pap Ame. 2012;243:7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branchini BR. Chemical synthesis of firefly luciferin analogs and inhibitors. J Biolum Chemilum. 2000;305:188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adjei AA. What is the right dose? The elusive optimal biologic dose in Phase I clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(25):4054–4055. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan KL, Xi JQ, Fan L, et al. In vivo guiding nitrogen-doped carbon nanozyme for tumor catalytic therapy. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1440. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03903-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao LZ, Fan KL, Yan XY. Iron Oxide Nanozyme: a multifunctional enzyme mimetic for biomedical applications. Theranostics. 2017;7(13):3207–3227. doi: 10.7150/thno.19738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cormode DP, Gao LZ, Koo H. Emerging biomedical applications of enzyme-like catalytic nanomaterials. Trends Biotechnol. 2018;36(1):15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu J, Lv W, Yang Q, et al. Label-free homogeneous electrochemical detection of MicroRNA based on target-induced anti-shielding against the catalytic activity of two-dimension nanozyme. Biosens Bioelectron. 2021;171:112707. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang T, Tian F, Long L, et al. Diagnosis of rubella virus using antigen-conjugated Au@Pt nanorods as nanozyme probe. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:4795–4805. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S171429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Lv W, Wu J, et al. In situ generated nanozyme-initiated cascade reaction for amplified surface plasmon resonance sensing. Chem Commun. 2020;56(33):4571–4574. doi: 10.1039/d0cc01117g.w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassidy CS, Lin J, Frey PA. A new concept for the mechanism of action of chymotrypsin: the role of the low-barrier hydrogen bond. Biochemistry. 1997;36(15):4576–4584. doi: 10.1021/bi962013o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groves K, Wilson RJ, Hamilton AD. Catalytic unfolding and proteolysis of cytochrome c induced by synthetic binding agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(40):12833–12842. doi: 10.1021/ja0317731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baugh SDP, Yang Z, Leung DK, et al. Cyclodextrin dimers as cleavable carriers of photodynamic sensitizers. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123(50):12488–12494. doi: 10.1021/ja011709o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B, Liu J. Surface modification of nanozymes. Nano Res. 2017;10(4):1125–1148. doi: 10.1007/s12274-017-1426-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.You CC, De M, Han G, et al. Tunable inhibition and denaturation of α-Chymotrypsin with amino acid-functionalized gold nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(37):12873–12881. doi: 10.1021/ja0512881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xi JQ, Wang WJ, Da LY, et al. Au-PLGA hybrid nanoparticles with catalase-mimicking and near-infrared photothermal activities for photoacoustic imaging-guided cancer therapy. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;4(3):1083–1091. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.You CC, Agasti SS, De M, et al. Modulation of the catalytic behavior of α-Chymotrypsin at monolayer-protected nanoparticle surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(45):14612–14618. doi: 10.1021/ja064433z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raina K, Crews CM. Targeted protein knockdown using small molecule degraders. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2017;39:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song YJ, Chen Y, Feng LY, et al. Selective and quantitative cancer cell detection using target-directed functionalized graphene and its synergetic peroxidase-like activity. Chem Commun. 2011;47(15):4436–4438. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05533f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De M, Chou SS, Dravid VP. Graphene oxide as an enzyme inhibitor: modulation of activity of α-Chymotrypsin. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(44):17524–17527. doi: 10.1021/ja208427j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Li SS, Yang HY, et al. Progress in the functional modification of graphene/graphene oxide: a review. RSC Adv. 2020;10(26):15328–15345. doi: 10.1039/d0ra01068e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Cheng P, Pu K. Recent advances of molecular optical probes in imaging of β-Galactosidase. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019;30(8):2089–2101. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holleran WM, Ginns E, Menon G, et al. Consequences of beta-glucocerebrosidase deficiency in epidermis. Ultrastructure and permeability barrier alterations in Gaucher disease. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1756–1764. doi: 10.1172/JCI117160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cha SH, Hong J, McGuffie M, et al. Shape-dependent biomimetic inhibition of enzyme by nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity. ACS Nano. 2015;9(9):9097–9105. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tripathi RM, Ahn D, Kim YM, et al. Enzyme mimetic activity of ZnO-Pd nanosheets synthesized via a green route. Molecules. 2020;25(11):2585. doi: 10.3390/molecules25112585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao K, Gu W, Zheng SS, et al. SDS-MoS2 nanoparticles as highly-efficient peroxidase mimetics for colorimetric detection of H2O2 and glucose. Talanta. 2015;141:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karunakaran S, Pandit S, De M. Functionalized two-dimensional MoS2 with tunable charges for selective enzyme inhibition. ACS Omega. 2018;3(12):17532–17539. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b02598 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett JW, Chung KT. Alexander Fleming and the discovery of penicillin. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2001;49:163–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taubes G. The bacteria fight back. Science. 2008;321(5887):356–361. doi: 10.1126/science.321.5887.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bebrone C, Lassaux P, Vercheval L, et al. Current challenges in antimicrobial chemotherapy. Drugs. 2010;70(6):651–679. doi: 10.2165/11318430-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ali SR, Pandit S, De M. 2D-MoS2-based β-lactamase inhibitor for combination therapy against drug-resistant bacteria. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2018;1(4):967–974. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.8b00105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornaglia G, Giamarellou H, Rossolini GM. Metallo-β-lactamases: a last frontier for β-lactams? Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(5):381–393. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70056-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poirel L, Naas T, Nicolas D, et al. Characterization of VIM-2, a carbapenem-hydrolyzing metallo-beta-lactamase and its plasmid- and integron-borne gene from a pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate in France. Antimicrob Agents Ch. 2000;44:891–897. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.4.891-897.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang PJJ, Pautler R, Shanmugaraj J, et al. Inhibiting the VIM-2 metallo-β-lactamase by graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2015;7(18):9898–9903. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b01954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oster G, Wang HY. Rotary protein motors. Trends Cell Bio. 2003;13(3):114–121. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00004-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Champagne E, Martinez LO, Collet X, et al. Ecto-F1F0 ATP synthase/F-1 ATPase: metabolic and immunological functions. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2006;17(3):279–284. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000226120.27931.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Junge W, Sielaff H, Engelbrecht S. Torque generation and elastic power transmission in the rotary F0F1-ATPase. Nature. 2009;459(7245):364–370. doi: 10.1038/nature08145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fillingame R, Jiang W, Dmitriev OY. Coupling H+ transport to rotary catalysis in F-type ATP synthases: structure and organization of the transmembrane rotary motor. J Exp Bio. 2000;203:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atwal KS, Ahmad S, Ding CZ, et al. N-[1-Aryl-2-(1-imidazolo) ethyl]-guanidine derivatives as potent inhibitors of the bovine mitochondrial F1F0 ATP hydrolase. ChemInform. 2003;4(23):1027–1030. doi: 10.1002/chin.200423143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shchepina L, Pletjushkina O, Avetisyan A, et al. Oligomycin, inhibitor of the F-0 part of H+-ATP-synthase, suppresses the TNF-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:8149–8157. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Atwal KS, Wang P, Rogers WL, et al. Small molecule mitochondrial F1F0 ATPase hydrolase inhibitors as cardioprotective agents. Identification of 4-(N-Arylimidazole)-substituted benzopyran derivatives as selective hydrolase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2004;47(5):1081–1084. doi: 10.1021/jm030291x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Z, Zhang Y, Yang Y, et al. Pharmacological and toxicological target organelles and safe use of single-walled carbon nanotubes as drug carriers in treating Alzheimer disease. Nanomed- Nanotechnol. 2010;6:427–441. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu J, Yuan B, Wu X, et al. Modulated enhancement in ion transport through carbon nanotubes by lipid decoration. Carbon. 2017;111:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2016.10.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.González-Durruthy M, Manske Nunes S, Ventura-Lima J, et al. Mitotarget modeling using ANN-classification models based on fractal SEM nano-descriptors: carbon nanotubes as mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase inhibitors. J Chem Inf Model. 2019;59(1):86–97. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]