Abstract

Root parasitic weeds infect numerous economically important crops, affecting total yield quantity and quality. A lack of an efficient control method limits our ability to manage newly developing and more virulent races of root parasitic weeds. To control the parasite induced damage in most host crops, an innovative biotechnological approach is urgently required. Strigolactones (SLs) are plant hormones derived from carotenoids via a pathway involving the Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase (CCD) 7, CCD8 and More Axillary Growth 1 (MAX1) genes. SLs act as branching inhibitory hormones and strictly required for the germination of root parasitic weeds. Here, we demonstrate that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targted editing of SL biosynthetic gene MAX1, in tomato confers resistance against root parasitic weed Phelipanche aegyptiaca. We designed sgRNA to target the third exon of MAX1 in tomato plants using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. The T0 plants were edited very efficiently at the MAX1 target site without any non-specific off-target effects. Genotype analysis of T1 plants revealed that the introduced mutations were stably passed on to the next generation. Notably, MAX1-Cas9 heterozygous and homozygous T1 plants had similar morphological changes that include excessive growth of axillary bud, reduced plant height and adventitious root formation relative to wild type. Our results demonstrated that, MAX1-Cas9 mutant lines exhibit resistance against root parasitic weed P. aegyptiaca due to reduced SL (orobanchol) level. Moreover, the expression of carotenoid biosynthetic pathway gene PDS1 and total carotenoid level was altered, as compared to wild type plants. Taking into consideration, the impact of root parasitic weeds on the agricultural economy and the obstacle to prevent and eradicate them, the current study provides new aspects into the development of an efficient control method that could be used to avoid germination of root parasitic weeds.

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Molecular biology, Plant sciences

Introduction

Parasitic plants are characterized as obligate or facultative parasites; they attach to either the shoot or the root, and they may be hemi or holoparasitic in nature1. Parasitic plants adopt different forms to invade host plants. Some, such as dodder (Cuscuta spp.) and mistletoe (Arceuthobium spp.) are aerial parts parasite, whereas Orobanchaceae such as Orobanche and Phelipanche aegyptiaca penetrate the underground root and represent one of the most destructive and great challenge for the agricultural economy1,2. P.aegyptiaca an obligate root parasitic plant causes great damage to economically important crops such as Solanaceae, Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Apiaceae and Brassicaceae plant families and affect total yields3. The life cycle of P. aegyptiaca have two stages, preparasitic and parasitic. The preparasitic stage involves seed preconditioning followed by germination of P. aegyptiaca seeds which is induced by presence of chemical inducer strigolactones (SLs) exuded by host plant roots4. However, the parasitic stage initiates with the parasite developing special projection or root like structure known as haustorium that directly penetrates the tissues of a host and absorbs nutrients and water5. After successful invasion and connection to the host root, the parasitic seedling grows into a bulbous structure known as tubercle from which a floral meristem emerges above the ground to produce flower and set seeds6.

SLs, a class of carotenoid-derived terpenoid lactones, is a plant hormone essentially required for inhibition of shoot branching and used as a signaling molecule for the rhizosphere microflora7,8. SL biosynthesis begins with DWARF 27 (D27) which catalyzes the isomerization in all-trans-β-carotene, followed by the combined activity of Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenases (CCDs) 7 and 8, leading to the production of carlactone (CL). First identified in Arabidopsis, MORE AXILLARY GROWTH 1 (MAX1), encodes a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase CYP711A subfamily member that acts as a CL oxidase to convert CL into carlactonoic acid which is further converted into various SLs9,10. Previous studies reported that in rice a MAX1 homolog catalyzes the conversion of CL to 4-deoxyorobanchol (4DO)11,12. A recent study, in tomato reported the direct conversion of carlactonoic acid into orobanchol by cytochrome P450, SlCYP722C which act as orobanchol synthase13. In the rhizosphere, SL acts as a host detection molecule for symbiotic arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and induces the germination of root parasitic weeds14,15. The existence of various types of SLs is reported such as strigol, 5-deoxystrigol, sorgolactone, solanacol, dideoxyorobanchol, orobanchol and others, which can act as germination inducer for root parasitic weeds16. Host resistance to root parasitic plant Striga has been reported in crops with decreased SL production17,18.

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated protein 9 and its derivative systems have become a powerful tool to induce various type of targeted mutagenesis at the genome level with high success in diverse organisms including tomato plants19–21. Cas9-mediated genome editing generates desired or random modifications at a specific target sequence depending on choice of Cas9 editor22. Cas9 nuclease induces site-specific double-strand DNA breaks at a targeted locus in the genome generating random modifications through non-homologous end-joining repair mechanisms, while Cas9 base editor has the capacity to replace the nucleotide at a specific target site23,24. The most frequently used CRISPR/Cas9 system, type II, has mainly three components: Cas9 nuclease, tracer RNA and crRNA. The 3′-end of the target sequence contains an NGG protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) that is recognized by the Cas9 protein25. CRISPR/Cas9 has been successfully demonstrated to edit the various plant genomes26,27. Here, in this study, we report the genome editing of MAX1 in tomato plants using CRISPR/Cas9 provides resistance against root parasitic weed P. aegyptiaca.

Results

Targeted mutagenesis of MAX1 gene in tomato using CRISPR/Cas9

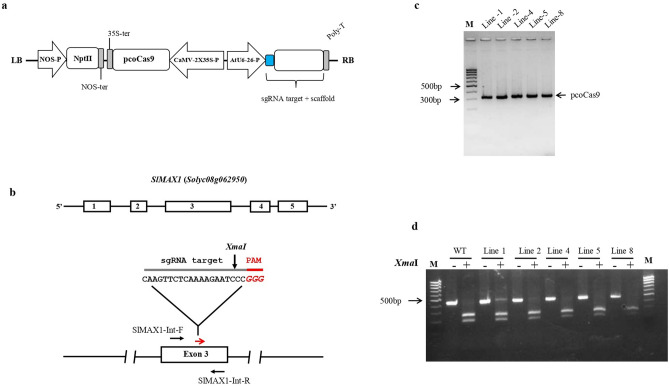

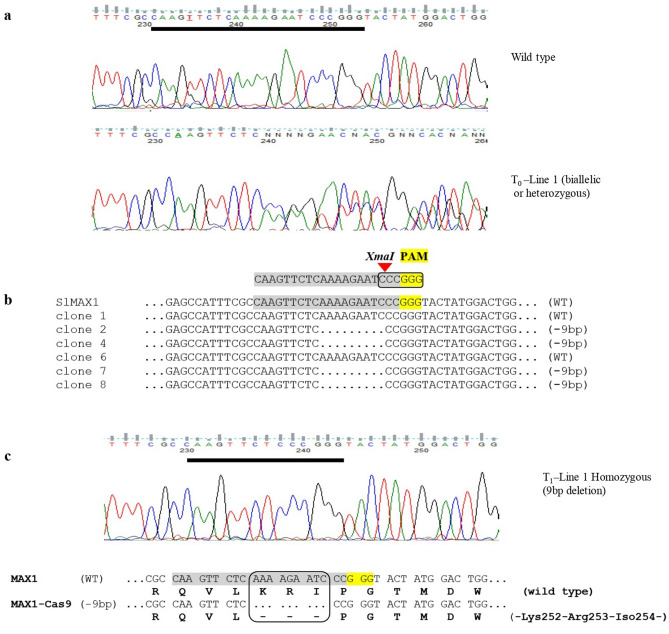

To analyze the effectiveness of the genome editing approach and to generate host resistance against root parasitic weed P. aegyptiaca, we targeted the SL-biosynthesis gene MAX1 (Solyc08g062950) in the host plant tomato using CRISPR/Cas9 system. The Cas9/sgRNA vector construct was designed to target the third exon of MAX1 (position 778–797 bp in the coding region) having an XmaI restriction site located next to the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) (Fig. 1a,b). Five transgenic lines 1, 2, 4, 5 and 8 were independently generated and presence of transgene was confirmed by kanamycin resistance and PCR amplification of pcoCas9 (Fig. 1c). To evaluate the types of mutation generated by Cas9/MAX1-sgRNA in T0 lines 1, 2, 4, 5 and 8, the flanking region was PCR amplified and the presence of indel mutations was tested by XmaI restriction digestion. Restriction analysis suggests that line 1 contained about equal amounts of undigested and digested DNA, in contrast other lines 2, 4, 5 and 8 seem non-mutants with most of the DNA digested similarly to wild type plants (Fig. 1d). DNA sequencing analysis of the target region from T0 line 1 shows multiple peaks possibly due to the presence of biallelic or heterozygous mutations (Fig. 2a), however in lines 2, 4, 5 and 8 no mutation was detected hence discarded. To explore the kind of mutation, existing in line 1, the MAX1 target region was PCR amplified and directly cloned into a TA cloning vector and sequenced. Analysis of the DNA sequences revealed that T0 line 1 plant is heterozygous and contains in-frame deletion of 9 nt which causes removal of the amino acid (Lys-252, Arg-253 and Iso-254) in mutant as compared to wild-type protein after Cas9-mediated editing of the target (Fig. 2b,c).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of Cas9/sgRNA binary vector, target sites and targeted mutagenesis. (a) The strong constitutive CaMV-2 × 35S promoter was used to express plant codon-optimized Cas9 and the Arabidopsis U6-26 promoter was used to express MAX1-sgRNA. (b) Representation of the tomato MAX1 genomic map and location of the sgRNA target site. The target sequence of sgRNA is shown in black color, the PAM is shown in red, black arrows indicate the primer (MAX1-Int-F and MAX1-Int-R) used for PCR amplification and red arrows indicate location of sgRNA target site, XmaI site marked with arrow. (c) Five independent T0 transgenic lines were generated by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. The presence of the transgene was confirmed by using pcoCas9-specific primers (323 bp). (d) Detection of mutations at MAX1 locus using PCR product restriction digestion. PCR fragments of MAX1-Cas9 targeted region in T0 lines from genomic DNA of transgenic plants were subjected to XmaI restriction digestion. Lines 1, 2, 4, 5 and 8 represent independent T0 transgenic plants; +, XmaI added; −, without XmaI. XmaI digested or non-digested PCR product were resolved using a 2% agarose gel for 60 min. Results shown that MAX1-Cas9 mutant line 1 contain equal amount of undigested and digested DNA, while other lines 2, 4, 5 and 8 show complete digestion, similar to control wild-type (WT). The full-length agarose gel blot represents the complete set of digested or non-digested PCR products run in independent wells of a single gel. Image was acquired using DNR Mini Lumi with UV light and Microsoft office was used to crop the image in appropriate size. M: DNA size ladder (100 bp).

Figure 2.

Identification of targeted editing events induced by CRISPR/Cas9 (a) DNA sequence chromatogram of MAX1-Cas9 targeted region, PCR product in the T0 lines shown multiple peaks. (b) PCR product sequence alignment of the MAX1-Cas9 T0 lines after TA cloning with the wild-type sequences (WT), deletion sizes (nt) are marked on the right side. (c) PCR product sequence alignment of the MAX1-Cas9 T1 homozygous lines which causes deletion of amino acid sequences (Lys252-Arg253-Iso254) from protein in mutated plant as compared to wild type.

Usually, T0 transgenic lines are somatic in nature, hence T0 line 1 was grown to maturity and self-pollinated to generate T1 plants. Genomic DNA was isolated from the T1 plants of line 1 and the target region of MAX1 was again amplified using PCR primers flanking the target. When this analysis was performed on T1 plants of line 1, results were like those with the T0 line 1. At least 64 plants of the T1 lines were analyzed for genotype at the target site using sanger DNA sequencing. T1 plants from the T0 heterozygous line 1 were segregated according to mendelian law and the kind of mutation that existed was separated as 1:2:1 as reported previously (Table S1)28. The existence of T0 mutation by T1 plants suggested that the mutation resulting from CRISPR/Cas9 activity are highly stable in nature and inherited to the next generation without any alteration. Additionally, the presence of the transgene region (pcoCas9) was examined in the T1 generation plants. Our results demonstrated that 35.7% (5/14) T1 plants were detected to be transgene-free (Table S1). We have also analyzed potential off-target effects that occurred due to non-specific activity of Cas9, associated with MAX1-sgRNA in the tomato genome. At least two plants were selected from the T1 generations of MAX1-Cas9 edited homozygous lines. Sequencing analysis of PCR products from these regions revealed no change in the potential off-target sites (Fig. S1, Table S2).

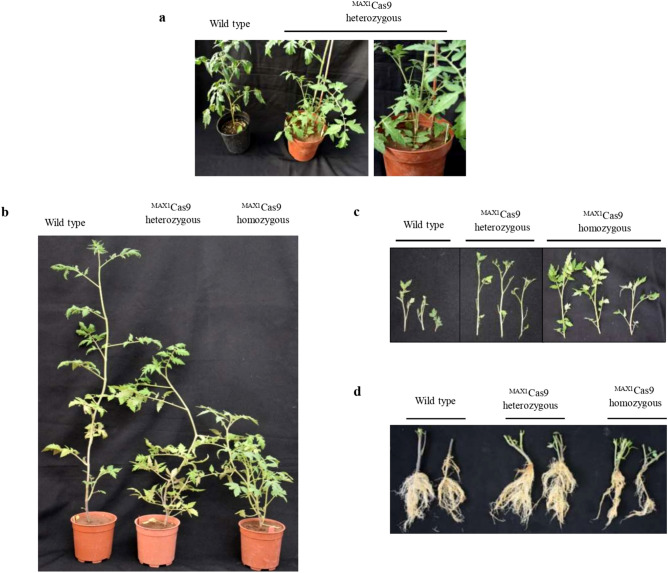

Alteration of morphological phenotype in MAX1-Cas9 mutated plants

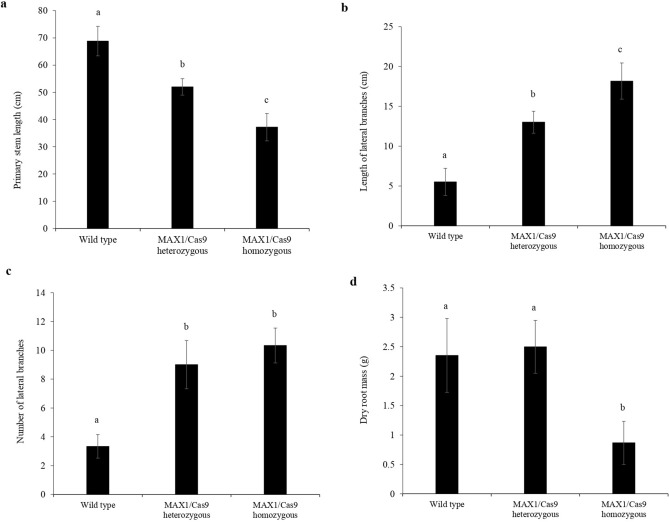

Previous studies with RNA silencing of MAX1 in tomato suggest that max1 mutants exhibit an increase in shoot branching, lateral roots and overall dwarfing29. Surprisingly, in our study, the heterozygous lines had shown more growth of axillary buds as compare to control even in T0 generation (Fig. 3a). Consistently, we also observed similar phenotypic changes in the MAX1-Cas9 mutated homozygous T1 plants such as decreased plant height (Figs. 3b, 4a), branched shoots and more growth of axillary buds (Figs. 3c, 4b), which are significantly increased in number as compared to the wild type plants (Figs. 4c, S2), additionally the mutated plants have a significant difference in their dry root mass as compared to control plants (Figs. 3d, 4d). In conclusion, we observed characteristic feature of SL biosynthesis defective mutant in the MAX1-Cas9 heterozygous T1 plants as compared to wild type plants but these phenotypic changes were mild in nature with respect to homozygous plants.

Figure 3.

Morphological phenotype associated with MAX1 edited tomato lines. (a) MAX1-Cas9 edited T0 heterozygous plant showing more growth of axillary buds as compare to wild type. (b) T1 heterozygous plant showing mild change in phenotype. Wild type plants with normal vegetative growth; MAX1-Cas9 edited T1 heterozygous and homozygous T1 line (c, d) Comparison of length of axillary branches & root morphology in the wild type and Cas9 mutants.

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of morphological phenotypes in MAX1 edited lines. (a) Quantitative estimate of primary stem length in 1-month-old MAX1-Cas9 mutated tomato plant average ± SE. (b) Length of lateral branches after 1 month of growth, average ± SE. (c): Number of lateral branches after 1 month of growth, average ± SE. (d) Quantitative estimate of dry root mass of wild type and MAX1-Cas9 mutant plants after 2 months of growth. Values are the average ± SE (n = 6). (Level not connected by same letters are significant, p < 0.05; Student’s t test).

MAX1 mutated host plant reduces germination of root parasitic weed P. aegyptiaca

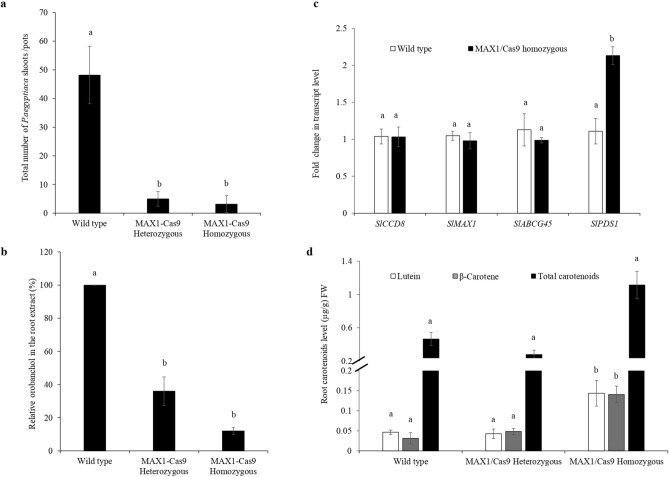

To evaluate, whether the MAX1-Cas9 mutated line show reduced germination of P. aegyptiaca, we selected MAX1-Cas9 heterozygous and homozygous tomato lines from T1 generation, and mixed with P. aegyptiaca seeds (15 mg/kg soil) and grown for three months in a greenhouse with optimum control conditions. To analyze the resistance, we counted only fresh and viable parasite tubercles and shoots that are larger than 2 mm in diameter. Results obtained suggested that the total number of germinated parasite tubercles and shoots were significantly reduced in the MAX1-Cas9 mutated heterozygous and homozygous plants as compared to the wild-type plants (Fig. 5a). To further correlate resistance to P. aegyptiaca infection and SL content of the MAX1-Cas9 mutated plants, we analyzed the total orobanchol content in the root extract of wild-type and MAX1-Cas9 edited host plants. We observed a significant reduction of total orobanchol content in both heterozygous and homozygous plants as compared to the wild type. However, the decrease in orobanchol was more pronounced in homozygous as compared to heterozygous mutant plants (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Resistance to parasitic infestation, real time PCR and carotenoid content analysis. To evaluate resistance to the root parasitic weeds, host roots of the tomato wild-type and MAX1-Cas9 mutated T1 lines were rinsed after 3 months of infestation with P. aegyptiaca seeds. Tubercles larger than 2 mm in diameter were counted for analysis. (a) Average number of P. aegyptiaca tubercles and shoots attached to the MAX1-Cas9 mutants and wild type tomato plants in the pot assay. Bars represent average of two experiments with six independent plants of each T1 mutants ± SD values. (b) Orobanchol contents in the roots of tomato MAX1-Cas9 edited plants as compared to wild type. LC–MS/MS analysis was done three times with three biological samples from each mutant. Data represented as average ± SD n (3). (c) Real time PCR analysis of CCD8, MAX1, ABCG45 and PDS1 transcript levels in the root of MAX1-Cas9 edited homozygous lines and wild type plants. Fold change in transcript level was shown after normalization with internal control tomato elongation factor-1α (EF1-α). Bars with different letters are significantly different from each other (student t-test at p < 0.05 when compared with the wild type). Result shown represent the mean of three experimental repeat ± SE. (d) Quantitative estimate of carotenoids content in the tomato root of wild type and MAX1-Cas9 mutant plants. Values are based on the analysis of 2 months old plants grown in green house with optimum conditions. Carotenoid analysis was done three times with three biological samples from each mutant. Data represented as average ± SD n (3). Statistical differences were calculated with Student’s one-tailed t-test (p < 0.05). Different small letter on the bar indicate a significant difference between the MAX1-Cas9 edited lines as compared to the wild type plants.

MAX1-Cas9 mutation affects upstream carotenoid-biosynthesis pathway

SLs are carotenoid derivatives and carotenoids are isoprenoid pigments that differ in structure and stereometric configuration with a system of conjugated double bonds that is responsible for their colors9,30. In plants, SL and carotenoid biosynthesis take place mainly in the plastids31. It is initiated by the condensation of two molecules of geranylgeranyl diphosphate and with a series of reactions in presence of different enzymes, they produce diverse active molecules such as lycopene, lutein, β -carotene and violaxanthin9,32. To assess whether targeted mutagenesis of MAX1 gene induces feedback regulation and affect transcript level of SL biosynthetic gene CCD8 and MAX1, expression analysis was performed in homozygous lines using quantitative real-time PCR, however, we did not observe any significant difference in the expression of CCD8 and MAX1 transcript (Fig. 5c). This data suggests that mutagenesis of MAX1 does not affect expression of CCD8 or the feedback pathway. Previous studies with Petunia hybrida ATP Binding Cassette transporter explored that PDR1 act as SL transporter which has a key role in regulating the growth of axillary branches and symbiotic interactions with arbuscular mycorrhizae. Additionally, P. hybrida pdr1 mutants are defective in SL exudation from their roots, resulting in reduced germination of P. ramosa33. To investigate whether the resistance against root parasitic weed depends on SL exporter the expression of ABCG45, a homolog of PDR1 in tomato, was analyzed in MAX1 mutants and we did not observe any significant change in the transcript, which suggest that ABCG45 is not involved in parasitic weed resistance mechanism (Fig. 5c). Further, to explore whether defective SL biosynthesis in MAX1-Cas9 mutant affects the behavior of the upstream carotenoid-biosynthesis pathway, we analyzed the expression of phytoene desaturase-1 (PDS1), a gene involved in the biosynthesis of β-carotene30,34. Our results demonstrated that the expression of PDS1 is significantly upregulated in MAX1-Cas9-edited homozygous T1 lines as compared to the wild type (Fig. 5c). To further validate the PDS1 expression data, we analyzed the total carotenoids content in the root of MAX1 mutated plants. Our results suggest that homozygous mutants have substantially increased content of total carotenoids along with β-carotene and lutein as compare to heterozygous and wild type plants (Fig. 5d).

Discussion

Plant-parasitic weeds exert biotic stresses and create significant constraints for farming and food production worldwide. Root parasite Phelipanche and Orobanche spp. attacks many economically important crops throughout the Mediterranean and semi-arid regions and are regarded as the most serious pests35. Hence, to control parasitic weeds effectively, an innovative solution is urgently needed. A major goal of plant genome editing is to improve crop yield and quality. Studies on host plant–parasitic weed interactions have explored many key host genes associated with parasitic weed resistance36–39.

In this study, using CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing system, we have developed a non-transgenic MAX1 mutant of tomato that exhibits reduced orobanchol content and increased resistance to P. aegyptiaca. We designed a sgRNA to target the third exon of the tomato MAX1 gene to disrupt SL biosynthesis. In Agrobacterium transformed T0 transgenic line, we found editing events in the MAX1 targeted locus in one (Line 1) out of five lines (Fig. 1). The heritability of the mutation and the generation of transgene-free plants are major concern, when using the CRISPR/Cas9 system40,41. To avoid the somatic nature of editing events, T0 line 1 was self-pollinated to generate T1 transgenic plants. In the T1 generation, we observed that the mutations induced in T0 line 1 are stably inherited by the T1 generation, without any new mutations (Fig. 2).

Using sanger DNA sequencing of potential off-target sites with mismatches of fewer than 4nt with MAX1-sgRNA, we did not identify any off-target mutation (Fig. S1 and Table S2). The specificity of Cas9 is greatly influenced by various factors and non-specific off-target site cleavage is a major challenge in the use of the CRISPR system42. In higher plants, undesirable mutations resulting from the CRISPR/Cas9 system are generally rare, however, non-specific undesired mutations can be avoided using more specific sgRNAs43–47.

SLs play a major role in controlling plant architecture, regulating shoot branching and to influence lateral and adventitious root formation48. Recent studies on the morphology of tomato max1-mutant plants by gene silencing have shown an increase in shoot branching, reduced plant height and increased adventitious roots formation49. Interestingly, in our study MAX1-Cas9 heterozygous tomato plants shown intermediate phenotype with respect to homozygous and wild type plants. These heterozygous plants displayed reduced plant height, increased number of axillary branches, nodes and adventitious roots compared to the wild-type plants (Figs. 3, 4). However, morphological phenotypic changes associated with heterozygous lines were mild in nature than homozygous plants.

In the view of above, an argument can be raised that transgenic plants bearing Cas9 expression cassette in their genome constitutively express Cas9-sgRNA throughout their life and mutation could be accumulated during growth that will affect phenotype in heterozygous plants. To support our results, we showed that homozygous plants generated from the same line showed no off-target effects. Moreover, our MAX1 heterozygous plant shows a characteristic phenotype of SL defective mutant though it is mild in nature. These results strongly support our data and provides an explanation of phenotypic defect in MAX1 heterozygous. Another explanation for this could be the heterozygous mutants (in-frame 9nt deletion) due to the absence of amino acid Lys252-Arg253-Iso254 in the mutated protein behaving as semi-dominant negative or it could be a dosage gene effect, where one normal copy of gene exists and one copy mutated, that could affect the normal growth of plants if the protein has a role in important cellular function however these explanations need to be thoroughly investigated.

To evaluate host resistance to P. aegyptiaca, we used a pot system containing soil infested with P. aegyptiaca seeds as described previously50. In the current study, coincidently with the suppression of SL content, a significant decrease in the number of total germinated parasite tubercles and shoots was observed in MAX1 mutated plants as relative to the wild type plants. In contrast, the wild-type plants were highly susceptible to the parasite infestation (Fig. 5a). Since orobanchol is a major SL in tomato root exudates51, and acts as a specific germination inducer for P. aegyptiaca, hence we determine the orobanchol content in the root extract of the MAX1-Cas9 mutated lines. Orobanchol content was found to be significantly reduced in the MAX1-mutated lines relative to the wild type (Fig. 5b).

Previously it has been reported that SLs are able to modulate local auxin levels, and the action of SL is dependent on the auxin status of the plant, suggesting that specific SL content influences the expression of genes involved in auxin biosynthesis52. Another study reported that an increase in transcript level of SL biosynthetic gene D27 and CCD8 in tomato roots occurs after parasitic weed infection, suggesting SL-biosynthesis pathway gets activated after parasitic infection53. Several studies reported that SL-biosynthetic pathways are strictly regulated by negative-feedback inhibition such as D10 transcript levels are elevated in the dwarf mutants (d10-1) of rice, similarly transcript level of RMS1 are enhanced in ramosus mutants of pea and application of synthetic SL GR24 restored the transcripts level54–56. To evaluate the role of MAX1 in feedback regulation and mechanism of resistance, we analyzed the transcript level of CCD8, MAX1 and ABCG45 (Fig. 5c). However, no alteration in transcript level was observed suggesting that possibly MAX1 did not involve in the control of feedback inhibition of SL pathway or carlactone accumulation has no role in modulation of SL biosynthetic pathway. Moreover, the expression of SL exporter ABCG45 was also unaffected. Interestingly in our study MAX1-mutated homozygous lines have increased levels of a carotenoid biosynthetic gene PDS1 and total carotenoids (Fig. 5d). These results indicate that block in the SL biosynthesis pathway positively affects carotenoid biosynthesis possibly due to interconnection between SL production and carotenoid biosynthesis.

Previous studies from our laboratories demonstrated the movement of mobile exogenous siRNA from the host to the root parasites50, this provides an insight that, CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique could be used against the parasite itself by indirectly transforming parasite-specific sgRNA in the hosts, if the host gene does not share sufficient homology with the targeted sequences of the parasite. The unwanted cleavage due to the non-specificity of the sgRNA within the genome exerts significant limitations to the CRISPR/Cas9 system which can alter the function of a gene or induce genomic instability. Currently, several naturally occurring and genetically modified Cas9 enzymes and specific sgRNA designing tools have been developed to enhance site specific target cleavage57–59, however, the off-target effect is still considered as a major limiting factor60. In the current study, we demonstrate that genetic resistance to root parasitic weeds can be obtained using CRISPR/Cas9 mediated targeted mutagenesis of the MAX1, a SL biosynthetic gene in tomato. A similar strategy could be effectively used against other parasitic weeds to generate host resistance.

Experimental procedures

Materials and growth conditions

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) cultivar MP-1 was chosen for generation of transgenic plants. Tomato seeds were surface-sterilized using 1% bleach with tween-20 and 70% ethanol and grown on half strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal medium (CAISSON Laboratories, USA) containing 1.5% sucrose (Sigma), pH 5.8 and 7 g/L phytagel (Sigma). The P. aegyptiaca seeds were collected from infected field in Northern Israel and used to infest tomato host plants.

sgRNA design and Cas9 vector construction

The tomato MAX1 (Solyc08g062950) gene was chosen as the target and sgRNA sequence of 20 nucleotides was designed using the CRISPR-P webtool and cloned into the plant binary vector. The binary vector contains nptII gene as kanamycin selection marker, under the control of the NOS promoter. sgRNA sequence together with the guide scaffold, was amplified using forward primer containing SalI site as part of the U6 Arabidopsis promoter and a reverse primer of the Pol III-terminator sequence that contained a HindIII site and pRCS35S:Cas9-AtU6:sgRNA-PDS was used as a template. The amplified DNAs (130 bp) were cloned into SalI and HindIII digested pRCS-35S:Cas9-AtU6:sgRNA-PDS vector61–63. The verification of positive clones was done using diagnostic PCR and sequencing. The construct was transformed into tomato cultivar MP-1 using Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105.

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of tomato plants

The transformation of tomato was conducted as previously described, with slight modifications64. The cotyledons were pre-cultured for 2 day in dark with Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium containing 100 μM Acetosyringone, 0.1 mg/L IAA, 1 mg/L Zeatin and 0.7% phytagel subsequently infected with the Agrobacterium strain EHA105 (optical density at 600 nm less than 0.5) by immersion for 20 min. The explants were co-cultivated with Agrobacterium strain EHA105 for two days in dark and then transferred to the MS medium supplemented with 0.1 mg/L IAA, 1 mg/L Zeatin, 100 µg/ml Kanamycin, 300 µg/ml timentin and 0.7% phytagel for a week. Kanamycin-resistant shoots regenerated were transferred to tissue culture bottles containing the subculture medium with 0.1 mg/L Zeatin. Developed vegetarians were transferred to the half strength MS rooting substrate with the addition of 2 mg/L IBA. After three months, Kanamycin-resistant plantlets were obtained and used for subsequent analysis.

Genotyping of transgenic plant

For genotyping, tomato plant leaves or roots genomic DNA was extracted using plant genomic DNA extraction kit and the genomic DNA flanks containing the sgRNA target sites were amplified using the specific primers SlMAX1-Int-F & SlMAX1-Int-R and then run on a 2% agarose gel using electrophoresis. Image was acquired using DNR Mini Lumi with UV light system. Direct sequencing of PCR products was done using appropriate primer. For PCR product cloning, pGEM-T kit from Promega were used.

Analysis of off-target mutations

The potential off-target sites associated with sgRNA target sequence were analyzed with the CRISPR-P program65. Three off target sites with the highest probability score were selected. The genomic region flanks upstream and downstream to the off-target sites (300–400 bp) was amplified and sequenced with specific primers using sanger DNA sequencing (Table S3).

Evaluation of P. aegyptiaca resistance assay

Resistance analysis of MAX1-Cas9 mutant tomato lines to the parasite was done as reported earlier 66. For infection one-month-old tomato seedlings were transferred into pots containing soil with a peat moss to perlite mixture ratio of 3:1, infested with seeds of P. aegyptiaca (15 mg/kg soil) and grown in a greenhouse under natural light with an average 14 h of daylight and a temperature of 20 ± 6 °C. Tomato plant roots from wild type and Cas9 mutant plants were collected, 3 months after exposure to the P. aegyptiaca seeds. The total number of viable P. aegyptiaca tubercles larger than 2 mm diameter attached to host roots were counted.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from tomato roots was extracted using spectrum plant total RNA kit (Sigma- STRN50-1KT) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 500 ng of total RNA was used to obtained cDNA according to the protocol of Quanta Bioscience cDNA Synthesis Kit. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in a volume of 10 μl using PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix ROX (Quanta biosciences) with 5 times diluted cDNA as template. Tomato elongation factor 1-α was used as an internal control gene. Specificity of the primers was confirmed by melting curve analysis. The generated Ct values of target genes were normalized to the Ct value of internal reference EF1-α gene. Relative expression was calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method and expressed as fold increase with respect to control67.

SL extraction and analysis using HPLC–MS/MS

The SL extraction and quantification were performed as described previously68. Lyophilized tomato roots were grounded into fine powders using liquid nitrogen and extracted with the ethyl acetate extraction method. The tissues were transferred to a 4–10 times volume of ethyl acetate. The flask was treated with an ultra-sonic bath for a few minutes and then placed in a cool place (4 °C) for 2–3 days. The tissues are filtered off and washed well with ethyl acetate. The combined ethyl acetate was washed with 0.2 M K2HPO4 or saturated NaHCO3 to remove acidic compounds. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4 or Na2SO4, filtered and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. Samples were dissolved in 2 ml acetonitrile or methanol: water (25:75 v/v) and the quantification of orobanchol in extracts was performed using LC–MS/MS using orobanchol as standard.

Carotenoid extract analysis

Carotenoid extract analysis was performed as reported earlier69. In brief, 1.5 g of fine grinded roots was used for extraction in presence of 8 ml hexane: acetone: ethanol (50:25:25 v/v), followed by 5 min of saponification in 1 ml of 8% (w/v) KOH. After addition of 1 ml of NaCl (25%), the saponified material was extracted twice with hexane, which was then evaporated in speed vacuum. The solid pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of ACN: MeOH: DCM (45:5:50 v/v) and passed through a 0.2 μm Nylon filter before HPLC analyses. Two independent biological samples from each line were pooled for carotenoid analysis.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, experiments were performed independently at least three times using three biological repeats and the results are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance difference was analyzed by Student’s t-test using JMP Pro 14 software. A p-value of < 0.05 was used as a cutoff for statistical significance that is indicated with different letters above the bar.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

V.K.B. and R.A. conceived the idea and planned the study, V.K.B. performed the molecular work such as vector construction, plant transformation and transgenic analysis. J.A.N. helped with P.aegyptiaca infestation, real time PCR and SL analysis. R.A. provided funding and intellectual contributions. V.K.B. finalized the data and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Vinay Kumar Bari, Email: vinay.bari@cup.edu.in.

Radi Aly, Email: radi@volcani.agri.gov.il.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-82897-8.

References

- 1.Westwood JH, et al. The evolution of parasitism in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(4):227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poulin R, Morand S. The diversity of parasites. Q. Rev. Biol. 2000;75(3):277–293. doi: 10.1086/393500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musselman JL. The biology of Striga, Orobanche and other root parasitic weeds. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1980;18:463–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.18.090180.002335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez-Aparicio M, Reboud X, Gibot-Leclerc S. Broomrape weeds. Underground mechanisms of parasitism and associated strategies for their control: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:135. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida S, et al. The Haustorium, a Specialized Invasive Organ in Parasitic Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2016;67:643–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-111702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rispail N, et al. Plant resistance to parasitic plants: Molecular approaches to an old foe. New Phytol. 2007;173(4):703–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Saint Germain A, et al. Novel insights into strigolactone distribution and signalling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013;16(5):583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waters MT, et al. Strigolactone signaling and evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017;68(68):291–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042916-040925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia KP, Baz L, Al-Babili S. From carotenoids to strigolactones. J. Exp. Bot. 2018;69(9):2189–2204. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seto Y, et al. Carlactone is an endogenous biosynthetic precursor for strigolactones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111(4):1640–1645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314805111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, et al. Rice cytochrome P450 MAX1 homologs catalyze distinct steps in strigolactone biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10(12):1028–1033. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoneyama K, et al. Conversion of carlactone to carlactonoic acid is a conserved function of MAX1 homologs in strigolactone biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2018;218(4):1522–1533. doi: 10.1111/nph.15055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakabayashi T, et al. Direct conversion of carlactonoic acid to orobanchol by cytochrome P450 CYP722C in strigolactone biosynthesis. Sci. Adv. 2019;5(12):9067. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouwmeester HJ, et al. Rhizosphere communication of plants, parasitic plants and AM fungi. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12(5):224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoneyama K, et al. Strigolactones, host recognition signals for root parasitic plants and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, from Fabaceae plants. New Phytol. 2008;179(2):484–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang YT, Bouwmeester HJ. Structural diversity in the strigolactones. J. Exp. Bot. 2018;69(9):2219–2230. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gobena D, et al. Mutation in sorghum LOW GERMINATION STIMULANT 1 alters strigolactones and causes Striga resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114(17):4471–4476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618965114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardoso C, et al. Natural variation of rice strigolactone biosynthesis is associated with the deletion of two MAX1 orthologs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111(6):2379–2384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317360111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157(6):1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatta BP, Malla S. Improving horticultural crops via CRISPR/Cas9: Current successes and prospects. Plants. 2020;9(10):1360. doi: 10.3390/plants9101360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang W, et al. Demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA-mediated targeted gene modification in Arabidopsis, tobacco, sorghum and rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(20):e188. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bortesi L, Fischer R. The CRISPR/Cas9 system for plant genome editing and beyond. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015;33(1):41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: Making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman JR, Taylor MR, Boulton SJ. Playing the end game: DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Mol. Cell. 2012;47(4):497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brazelton VA, Jr, et al. A quick guide to CRISPR sgRNA design tools. GM Crops Food. 2015;6(4):266–276. doi: 10.1080/21645698.2015.1137690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song GY, et al. CRISPR/Cas9: A powerful tool for crop genome editing. Crop Journal. 2016;4(2):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2015.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li C, Zhang B. Genome editing in cotton using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1902:95–104. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8952-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, et al. The CRISPR/Cas9 system produces specific and homozygous targeted gene editing in rice in one generation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014;12(6):797–807. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomez-Roldan V, et al. Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature. 2008;455(7210):189–194. doi: 10.1038/nature07271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nisar N, et al. Carotenoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant. 2015;8(1):68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun T, et al. Carotenoid Metabolism in Plants: The Role of Plastids. Mol Plant. 2018;11(1):58–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clotault J, et al. Expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes during carrot root development. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59(13):3563–3573. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kretzschmar T, et al. A petunia ABC protein controls strigolactone-dependent symbiotic signalling and branching. Nature. 2012;483(7389):341–344. doi: 10.1038/nature10873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan H, et al. Carotenoid metabolism and regulation in horticultural crops. Hortic. Res. 2015;2:15036. doi: 10.1038/hortres.2015.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubiales D, Vurro M, Murdoch AJ, Joel DM. Parasitic plant management in sustainable agriculture. Weed Res. 2009;49:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3180.2009.00741.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aly R, et al. Gene silencing of mannose 6-phosphate reductase in the parasitic weed Orobanche aegyptiaca through the production of homologous dsRNA sequences in the host plant. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2009;7(6):487–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao B, et al. TaD27-B gene controls the tiller number in hexaploid wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020;18(2):513–525. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohlen W, et al. The tomato CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE8 (SlCCD8) regulates rhizosphere signaling, plant architecture and affects reproductive development through strigolactone biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2012;196(2):535–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogel JT, et al. SlCCD7 controls strigolactone biosynthesis, shoot branching and mycorrhiza-induced apocarotenoid formation in tomato. Plant. J. 2010;61(2):300–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks C, et al. Efficient gene editing in tomato in the first generation using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-Associated9 system. Plant Physiol. 2014;166(3):1292–1297. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.247577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan C, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient and heritable targeted mutagenesis in tomato plants in the first and later generations. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24765. doi: 10.1038/srep24765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tycko J, Myer VE, Hsu PD. Methods for optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing specificity. Mol. Cell. 2016;63(3):355–370. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolt JD, et al. Achieving plant CRISPR targeting that limits off-target effects. Plant Genome. 2016;9(3):12. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2016.05.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Upadhyay SK, et al. RNA-guided genome editing for target gene mutations in wheat. G3. 2013;3(12):2233–2238. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.008847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen SJ. Minimizing off-target effects in CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Cell. Biol. Toxicol. 2019;35(5):399–401. doi: 10.1007/s10565-019-09486-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bortesi L, et al. Patterns of CRISPR/Cas9 activity in plants, animals and microbes. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 2016;14(12):2203–2216. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hajiahmadi Z, et al. Strategies to increase on-target and reduce off-target effects of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(15):1. doi: 10.3390/ijms20153719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brewer PB, Koltai H, Beveridge CA. Diverse roles of strigolactones in plant development. Mol. Plant. 2013;6(1):18–28. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang YX, et al. The tomato MAX1 homolog, SlMAX1, is involved in the biosynthesis of tomato strigolactones from carlactone. New Phytol. 2018;219(1):297–309. doi: 10.1111/nph.15131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dubey NK, et al. Enhanced host-parasite resistance based on down-regulation of Phelipanche aegyptiaca target genes is likely by mobile small RNA. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1574. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lopez-Raez JA, et al. Tomato strigolactones are derived from carotenoids and their biosynthesis is promoted by phosphate starvation. New Phytol. 2008;178(4):863–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agusti J, et al. Strigolactone signaling is required for auxin-dependent stimulation of secondary growth in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(50):20242–20247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111902108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres-Vera R, et al. Expression of molecular markers associated to defense signaling pathways and strigolactone biosynthesis during the early interaction tomato-Phelipanche ramosa. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016;94:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2016.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arite T, et al. DWARF10, an RMS1/MAX4/DAD1 ortholog, controls lateral bud outgrowth in rice. Plant J. 2007;51(6):1019–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foo E, et al. The branching gene RAMOSUS1 mediates interactions among two novel signals and auxin in pea. Plant Cell. 2005;17(2):464–474. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snowden KC, et al. The Decreased apical dominance1/Petunia hybrida CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE8 gene affects branch production and plays a role in leaf senescence, root growth, and flower development. Plant Cell. 2005;17(3):746–759. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.027714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu G, Zhang Y, Zhang T. Computational approaches for effective CRISPR guide RNA design and evaluation. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020;18:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schindele P, Wolter F, Puchta H. CRISPR guide RNA design guidelines for efficient genome editing. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020;2166:331–342. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0712-1_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang D, et al. CRISPR/Cas: A powerful tool for gene function study and crop improvement. J. Adv. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang XH, et al. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e264. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dafny-Yelin M, Tzfira T. Delivery of multiple transgenes to plant cells. Plant. Physiol. 2007;145(4):1118–1128. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.106104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li JF, et al. Multiplex and homologous recombination-mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31(8):688–691. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nekrasov V, et al. Targeted mutagenesis in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana using Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31(8):691–693. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCormick S, et al. Leaf disc transformation of cultivated tomato (L. esculentum) using Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Plant Cell Rep. 1986;5(2):81–84. doi: 10.1007/BF00269239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lei Y, et al. CRISPR-P: A web tool for synthetic single-guide RNA design of CRISPR-system in plants. Mol. Plant. 2014;7(9):1494–1496. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bari VK, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE 8 in tomato provides resistance against the parasitic weed Phelipanche aegyptiaca. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47893-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoneyama K, et al. Nitrogen deficiency as well as phosphorus deficiency in sorghum promotes the production and exudation of 5-deoxystrigol, the host recognition signal for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and root parasites. Planta. 2007;227(1):125–132. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0600-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tadmor Y, et al. Comparative fruit colouration in watermelon and tomato. Food Res. Int. 2005;38(8–9):837–841. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.