Abstract

Objective

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use has risen substantially, primarily driven by ongoing use over months to years. However, there is no consensus on how to define long-term PPI use. Our objectives were to review and compare definitions of long-term PPI use in existing literature and describe the rationale for each definition. Moreover, we aimed to suggest generally applicable definitions for research and clinical use.

Design

The databases PubMed and Cochrane Library were searched for publications concerning long-term use of PPIs and ClinicalTrials.gov was searched for registered studies. Two reviewers independently screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts in two series and subsequently extracted data.

Results

A total of 742 studies were identified, and 59 met the eligibility criteria. In addition, two ongoing studies were identified. The definition of long-term PPI use varied from >2 weeks to >7 years. The most common definition was ≥1 year or ≥6 months. A total of 12/61 (20%) of the studies rationalised their definition.

Conclusion

The definitions of long-term PPI treatment varied substantially between studies and were seldom rationalised.

In a clinical context, use of PPI for more than 8 weeks could be a reasonable definition of long-term use in patients with reflux symptoms and more than 4 weeks in patients with dyspepsia or peptic ulcer. For research purposes, 6 months could be a possible definition in pharmacoepidemiological studies, whereas studies of adverse effects may require a tailored definition depending on the necessary exposure time. We recommend to always rationalise the choice of definition.

Keywords: acid secretion, proton pump inhibition, pharmacology

Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are commonly used drugs worldwide. In Denmark, PPI prescriptions are redeemed by more than 10% of the population each year.1 Incident and prevalent PPI use are rising, the latter driven primarily by ongoing use over months to years.2 3 This has raised questions about whether continuous PPI therapy is actually needed in many patients. Around 40% of PPI users may be treated without an ongoing registered indication4 and concerns have been raised about possible adverse effects, specifically related to use of PPIs over months to years.5 Only 4–8 weeks of treatment with PPIs can cause rebound acid hypersecretion and acid-related symptoms in previously asymptomatic individuals,6 7 potentially contributing to continued use of PPIs.

Trends in PPI use have been intensely investigated in recent years, with studies consistently referring to long-term PPI use. However, there is no consensus on how to define long-term PPI use8 and the definitions of long-term use vary between studies. Substantial discrepancies in definitions of long-term use make it difficult to draw firm overall conclusions about the prevalence and impact of extended continuous PPI therapy and about discontinuation of long-term PPI therapy.

An appropriate uniform definition of long-term use of PPIs is relevant in a clinical context. Position statements or guidelines have provided comprehensive and rational clinical advice concerning long-term use but have not provided a clear definition of what long-term use is.9 10 This makes it challenging in clinical practice to determine whether and when a patient is considered a long-term user and to decide when deprescribing can be discussed.

Therefore, the objectives of this study are to review and compare definitions of long-term PPI use which have been used in the literature and explore the rationale for each definition. Furthermore, we aim to suggest a generally applicable definition of long-term use of PPIs for research and clinical use.

Materials and methods

To fulfil our aim of mapping the literature with a clear definition of long-term PPI use and clarifying the definition of long term, we chose a scoping review methodology.11 Guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Checklist for scoping reviews,12 we searched the databases PubMed and Cochrane Library for publications concerning long-term use of PPIs. The final PubMed and Cochrane searches were conducted in January 2019. The literature searches were assisted by a research librarian with expertise in medical literature databases. The search was conducted using the search terms “long-term AND proton pump inhibitor” using the title/abstract option in the search builder.

We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov in February 2019 for registered ongoing studies using the above-mentioned search terms.

Study selection

Two reviewers (PFH and SR) manually screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts independently in two series. In the screening of titles and abstracts, studies were excluded by the following criteria: (1) articles published before 2003, (2) articles not written in English or a Scandinavian language, (3) case reports, (4) animal studies, (5) use of PPI for less than 2 weeks.

During the assessment of full texts, we further excluded studies without a timeframe for long-term use. Only studies with a concrete definition of long-term use were included, hence studies using definitions perceived as indirect or vague, leaving the interpretation to the authors, were excluded. Any uncertainties and disagreements throughout the study selection process were discussed and resolved by consensus among PFH and SR.

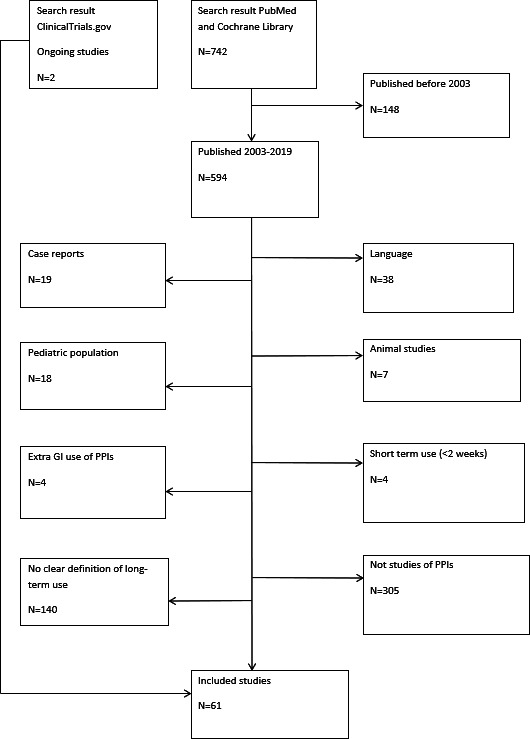

Figure 1 illustrates the study selection.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process. GI, gastrointestinal; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors.

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (PFH and SR) with respect to year, country, setting, study design, aim, definition of long-term use and rationale for choice of definition. Any discrepancies, disagreements or uncertainties were discussed between SR and PFH and agreement was established.

Results

The literature search identified a total of 742 studies in PubMed and Cochrane Library, of which 59 met the final eligibility criteria. By searching ClinicalTrials.gov we identified two ongoing studies, resulting in a total of 61 studies.

The selected studies concerned various aspects of long-term PPI use: adverse effects (n=35), treatment effects (n=13), pharmacoepidemiological studies (n=5) and discontinuation or dosage reduction (n=8). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the included studies, which contained 28 different definitions of long-term use.

Table 1.

Overview of the included studies

| Definition based on time (n=51) | ||||||

| Studies of side effects related to long-term PPI use (n=29) | ||||||

| Author, year | Country | Setting | Study design | Aim | Definition of long-term use | Rationale |

| Haastrup et al, 20185 | Denmark | N/A | Review | Overview of side effects of long-term PPI use | >2 weeks | Earlier studies showing no important side effects if used ≤2 weeks |

| Revaiah et al, 201820 | India | Secondary sector | Single-centre, cross-sectional | Risk of small bacterial overgrowth in PPI users | >3 months | No |

| Torvinen-Kiiskinen et al, 201821 | Finland | Primary sector | Case–control | Risk of hip fractures among community-dwelling residents with Alzheimer’s | ≥1 year | No |

| Biyik et al, 201722 | Turkey | Outpatient gastroenterology clinic | Cohort study | Risk of hypomagnesaemia in PPI users | ≥6 months | No |

| Takahari et al, 201723 | Japan | Secondary sector | Cross-sectional | Frequency of gastric cobblestone-like lesions in PPI users undergoing endoscopy | ≥6 months | No |

| Lochhead et al, 201724 | USA | Nurses’ health study | Cross-sectional | Association between PPI use and cognitive function | ≥2 years | No |

| Kearns et al, 201725 | UK | Primary sector | Case–control | Association between PPI use and pancreatic cancer | >2 years | Avoiding reverse causation |

| Targownik et al, 201726 | Canada | General population | Cross-sectional | Association between PPI use and bone structure | ≥5 years | No |

| Bahtiri et al, 201727 | Turkey | General population | Cohort | Risk of hypomagnesaemia | 12 months | No |

| Huang et al, 201628 | Taiwan | General population | Cohort | Association between PPI use and risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis | >180 days | No |

| Takeda et al, 201529 | Japan | Outpatients | Cross-sectional | Prevalence of hypomagnesaemia | >1 year | No |

| Lundell et al, 201514 | N/A | Systematic review | Systematic review | Effects of PPI on serum gastrin levels and gastric histology | >48 months | FDA requesting 3-year safety data from manufacturers |

| Song et al, 201430 | Cochrane review | N/A | Systematic review | Risk of gastric pre-malignant lesions in PPI users | ≥6 months | No |

| Lewis et al, 201431 | Australia | General population | Cohort | PPIs and risk of falls and fractures in elderly women | ≥1 year | No |

| Helgadóttir, 201432 | Iceland | Secondary sector | Cross-sectional | Serum gastrin levels in PPI users | ≥2 years | No |

| Bektas et al, 201233 | Turkey | Secondary sector | Cross-sectional | ECL hyperplasia in PPI users | ≥6 months | No |

| Pregun et al, 201134 | Hungary | Secondary sector | Cohort | Effect of PPI on serum chromogranin-A and gastrin levels | >6 months | No |

| Sarzynski et al, 201135 | USA | Primary sector | Retrospective cohort | Association between PPI use and iron-deficiency anaemia | >1 year | No |

| Fujimoto and Hongo, 201136 | Japan | Multicentre | Cohort | Efficacy and safety of 104 weeks treatment with rabeprazole | 104 weeks | No |

| Lombardo et al, 201037 | Italy | Secondary sector | Cohort | Incidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth among PPI users | >2 months | No |

| Yoshikawa et al, 200938 | Japan | Secondary sector | Case–control | Body mass index changes during PPI therapy in patients with GORD | >10 months | No |

| Ally et al, 200939 | USA | Outpatient clinic | Retrospective | Risk of fundic gastric polyps in PPI users | >48 months | No |

| Van Soest et al, 200840 | The Netherlands | General practice | Case–control | Risk of colorectal cancer among PPI users | >365 days within 5 years | No |

| Hashimoto et al, 200741 | Japan | Secondary sector | Clinical trial | PPI-induced tolerance to histamine-2-receptor antagonists | >4 weeks | No |

| Yang et al, 200742 | UK | General practice | Case–control | Risk of colorectal cancer among PPI users | ≥5 years cumulative use | The definition is argued to be able to demonstrate an accelerative effect on the transformation from adenomas to carcinomas |

| Robertson et al, 200743 | Denmark | Population based | Case–control | Risk of colorectal cancer among PPI users | >7 years | The definition is argued to be able to demonstrate an accelerative effect on the transformation from adenomas to carcinomas |

| Jalving et al, 200644 | The Netherlands | Secondary sector | Cross-sectional | Risk of fundic gastric polyps in PPI users | ≥1 years | No |

| Hritz et al, 200545 | Hungary | Secondary sector | Clinical trial | Effect of PPI on gastric cell proliferation | 6 months | No |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | Austria | Secondary sector | Clinical trial | Intestinal microbiota in PPI users | ≥6 months | No |

| Studies of treatment effects of long-term PPI use (n=13) | ||||||

| Kiso et al, 201746 | Japan | Outpatient clinic | Cross-sectional | Endoscopic findings in patients undergoing gastric screening | >8 weeks | No |

| Funaki et al, 201747 | Japan | Outpatient clinic | Cross-sectional | Efficacy of PPI in patients with NERD with and without irritable bowel syndrome | >6 months | ROME III criteria for functional disorders (duration >6 months) |

| Hatlebakk et al, 201648 | Europe (several countries) | Secondary sector | RCT | Comparing anti-reflux surgery with PPI treatment in patients with chronic GERD | 5 years | No |

| Yoon et al, 201449 | South Korea | HP-positive patients | RCT | Eradication rates with different durations of pretreatment with PPI | ≥56 days | No |

| Poh et al, 201117 | USA | Outpatient clinic | RCT | Comparing stimulus response functions to acid in users and non-users of PPI undergoing acute stress | 8 weeks | No |

| Labenz et al, 200950 | Sweden | Secondary sector | RCT | Predictors of symptom resolution in patients with GERD during maintenance PPI therapy | >6 months | Maintenance phase after healed oesophagitis |

| Sugano et al, 201351 | Japan | Outpatient clinic | Clinical trial | Gastroprotective effect of omeprazole | 1 year | No |

| Fujimoto and Hongo, 201052 | Japan | Secondary sector | Cohort | Relapse of GERD during long-term PPI therapy | 104 weeks | No |

| Kandil et al, 201015 | Egypt | Outpatient clinic | Cohort | Effect of exogenous melatonin in patients with GERD | 4 and 8 weeks | No |

| Mason et al, 200853 | UK | General practice | RCT | Effect of HP eradication in long-term users of PPI | A repeat prescription for PPI begun at least 12 months ago | Previous article by Hungin et al54 |

| Raghunath et al, 200955 | UK | Primary care | Cross-sectional | Symptoms in patients on long-term PPI therapy | A repeat prescription for PPI begun at least 12 months ago | Previous article by Hungin et al54 |

| Usai et al, 200816 | Italy | Secondary sector | Cohort | Recurrence of reflux symptoms in patients with coeliac disease with NERD | >8 weeks | No |

| Frazzoni et al, 200756 | Italy | Secondary sector | Cohort | Efficacy of long-term PPI on intraoesophageal acid suppression | 2 years of continuous use | No |

| Studies of deprescribing long-term PPI (n=6) | ||||||

| Pezeshkian and Conway, 201857 | USA | N/A | Review | Guidance on deprescribing PPI in older adults | >12 weeks | Approved duration of treatment |

| Boghossian et al, 201758 | Cochrane review | N/A | Systematic review | Effects of deprescribing PPI in adults | ≥28 days | No |

| Walsh et al, 201659 | Canada | General practice | Cross-sectional | Deprescribing | ≥8 weeks | Guideline recommending reassessment of PPIs after 8 weeks |

| Van der Velden et al, 201360 | The Netherlands | Primary care | RCT | Deprescribing | ≥1 year | No |

| Bjornsson et al, 200661 | Sweden | Secondary sector | Clinical trial | Discontinuation | >8 weeks | No |

| Krol et al, 200462 | The Netherlands | General practice | RCT | Discontinuation | ≥12 weeks | No |

| Pharmacoepidemiological studies of long-term PPI use (n=3) | ||||||

| Othman et al, 201663 | UK | General population | Cohort | Prevalence and pattern of PPI prescribing | ≥1 year continuous use | No |

| Lødrup et al, 201464 | Denmark | General population | Survey | Use of PPIs | ≥120 days the past year | No |

| Haroon et al, 201365 | Ireland | Secondary sector | Survey | Reasons for treatment | 2 years | No |

| Definition based on quantity of PPI (n=10) | ||||||

| Studies of side effects related to long-term PPI use (n=6) | ||||||

| Imfeld et al, 201866 | UK | General population | Case–control | Risk of dementia | ≥100 prescriptions | No |

| Shao et al, 201867 | Taiwan | General population | Case–control | Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma | >28 DDDs | No |

| Sieczkowska et al, 201868 | Poland | Outpatient clinic and general practice | Cohort | Risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth | PPI for at least 75% of the time during the previous 3 months at a minimum dose of 20 mg per day | No |

| Chien et al, 201669 | Taiwan | General population | Case–control | Risk of periampullar cancer | >180 DDDs | No |

| Clooney et al, 201670 | Canada | General population | Cross-sectional | Gut microbiome in long-term PPI users | >180 tablets each year in a 5-year period | No |

| Den Elzen et al, 200871 | The Netherlands | General population | Cross-sectional | Risk of vitamin B12 deficiency | >810 DDDs in 3 years | No |

| Studies of deprescribing long-term PPI (n=2) | ||||||

| Reimer and Bytzer, 201072 | Denmark | Primary care | Cross-sectional | Discontinuation in symptomatically treated patients | 120 tablets of any PPI in the previous 12 months | No |

| Clinicaltrials.gov | USA | Primary care | Clinical trial | Evaluation of a deprescribing programme | 90-day prescription within 120 days | No |

| Pharmacoepidemiological studies of long-term PPI use (n=2) | ||||||

| Wallerstedt et al, 20174 | Sweden | General population | Cross-sectional | Prevalence of PPI use among residents ≥65 years | Filled prescriptions for PPI covering ≥75% of the year | No |

| Haastrup et al, 20162 | Denmark | General population | Cohort | Predictors of incident long-term use among first-time users | >60 DDDs within 6 months | Definition used in other studies |

DDDs, defined daily doses; ECL, enterochromaffin-like; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; GERD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; HP, Helicobacter pylori; N/A, not available; NERD, non-erosive reflux disease; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

The threshold for defining long-term PPI use varied from >2 weeks to >7 years of PPI use. The most common definition was ≥1 year (10 studies) or ≥6 months (10 studies). Nine studies defined long-term use as ≥8 weeks. A total of 10 studies used number of prescriptions, number of tablets or defined daily dose (DDD) in their definition. However, there was substantial variability in DDD/unit of time to define long-term use. Four studies used repeat prescriptions to define long-term use.

A total of 12 out of 61 studies (20 %) stated a specific explanation for their choice of long-term definition. Most studies rationalised their choice by referring to previous studies, guidelines or policy papers.

The definition of long-term use also varied within publications by the same author. In a study by Lundell et al from 2009,13 long-term treatment was defined as >8 weeks when examining treatment failure in the follow-up of treatment effect. Six years later, Lundell et al defined long-term use as >3 years when studying the effects of long-term PPI use on serum gastrin levels and gastric histology.14

Discussion

Main findings

In our review we were able to identify 61 studies on different aspects related to long-term use of PPIs. The definitions of long-term use varied substantially between studies and consensus in the literature on how to define long-term use of PPIs is lacking. One in five studies stated an explanation for their choice of definition.

Comparison with previous literature

To our knowledge this is the first study systematically assessing the different definitions used in studies of long-term use of PPIs. In a review from 2005, Raghunath et al8 mention that there is no consensus on how to define long-term use and state the definitions used in some previous studies without attempting to establish a consensus-based definition. Additionally, a substantial amount of studies have emerged since 2005 and a new evaluation was required.

Implications

The substantial variability in definitions of long-term use makes it challenging to compare studies in this area. For example, it is difficult to compare the range, burden and magnitude of extended continuous PPI therapy when definitions of ‘long-term’ use vary widely. More uniform definitions could improve these aspects and allow for more reliable conclusions to be drawn across available studies.

In a clinical context, several guidelines on PPI prescribing exist, but definitions of long-term use are often lacking. An appropriate time to discuss ongoing use may be after an initial course of PPI is finished (eg, at 2–4 weeks for uninvestigated dyspepsia) to avoid ongoing use without indication. For several studies of patients with non-erosive reflux disease/gastro-oesophageal reflux disease identified in this review, long-term use was defined as using >4 or >8 weeks.15–17 This may reflect the fact that efficacy trials demonstrate healing of oesophagitis with 4–8 weeks of PPI, which is also reflected in guideline recommendations.18

Once the recommended initial evidence-based course is completed and patients continue PPI treatment after 2–4/8 weeks (depending on whether the indication was dyspepsia, peptic ulcer or reflux), they could be considered long-term users. At this point, some patients may no longer require continuous PPI (from an efficacy/indication standpoint) and the indication for ongoing therapy could be discussed. However, it is unclear whether this currently happens widely in practice. Therefore, we suggest discussing appropriate PPI therapy with the patient after 2–4 weeks if the indication is uninvestigated dyspepsia and after 4–8 weeks if the indication is reflux symptoms where long-term treatment often is necessary.

From a research perspective, the optimal definition of long-term use may depend on the aim of the study. Long-term use most likely needs to be defined differently if the aim is to study side effects occurring after years of continuous use versus studying pharmacoepidemiological aspects of PPI use such as drug utilisation or characteristics of patients using PPIs or of doctors prescribing PPIs. As an example, the inconsistency in the definitions used by Lundell et al is probably due to a deliberate selection of definitions expedient to the given research aim.

The most appropriate definition may also depend on whether the aim is to study aspects of only continuous daily use of PPI or the aim is to include intermittent use of PPIs as well. It has been demonstrated that many patients use PPI sporadically and only a minority are taking PPIs continuously.19 When choosing a definition of long-term use, it is important to keep in mind that restricting the definition to continuous daily use might exclude the many PPI users from the study population.

Therefore, it is not possible to have just one definition of long-term use that is appropriate for all research purposes and the definition used should fit the aim and context of the study. If the aim is to study drug utilisation or magnitude of long-term use, we suggest a long-term definition of 6 months as a possible definition. Most PPIs are supplied in packages of no more than 100 pills. Thus, taking PPIs daily for 6 months would require at least one renewal of the prescription. Patients initially redeeming 100 pills, but not using all of them, would not be classified as long-term users.

If the aim is to study side effects related to long-term use, the definition of long term might need to be shorter or longer than 6 months depending on the length of exposure time needed for the side effect to occur.

In conclusion, we observed substantial variability in definitions of long-term PPI treatment. The majority of definitions did not include a rationale for the choice of definition. The variety of definitions complicates the comparison of research results and raises challenges in clinical practice, such as identifying an appropriate timeframe for discussing deprescribing. We suggest that long-term use could be defined as more than 4–8 weeks of PPI use in a clinical context depending on the indication for PPI therapy. One definition does not fit all research purposes. Thus, we suggest more than 6 months of PPI use as a possible definition for long-term use in pharmacoepidemiological studies and for studies of adverse effects the definition should be tailored the exposure time needed for the side effect in question to occur. When studying long-term use of PPIs, we suggest always giving well-argued choices of definitions.

Acknowledgments

We thank research medical librarian emeritus, Johan Wallin, for assistance with the literature search.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of the study. The literature selection process and data extraction were done by PFH and SR. PFH drafted the first version of the manuscript and all authors contributed with comments and suggestions for improvement. All authors accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Data may be obtained from the included studies available through public databases.

References

- 1.The Danish health data authority. Available: https://medstat.dk/ [Accessed Mar 2019].

- 2.Haastrup PF, Paulsen MS, Christensen RD, et al. . Medical and non-medical predictors of initiating long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: a nationwide cohort study of first-time users during a 10-year period. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:78–87. 10.1111/apt.13649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lassen A, Hallas J, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Use of anti-secretory medication: a population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:577–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02120.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallerstedt SM, Fastbom J, Linke J, et al. . Long-Term use of proton pump inhibitors and prevalence of disease- and drug-related reasons for gastroprotection-a cross-sectional population-based study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017;26:9–16. 10.1002/pds.4135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haastrup PF, Thompson W, Søndergaard J, et al. . Side effects of long-term proton pump inhibitor use: a review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2018;123:114–21. 10.1111/bcpt.13023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reimer C, Søndergaard B, Hilsted L, et al. . Proton-Pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology 2009;137:80–7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niklasson A, Lindström L, Simrén M, et al. . Dyspeptic symptom development after discontinuation of a proton pump inhibitor: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1531–7. 10.1038/ajg.2010.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raghunath AS, O'Morain C, McLoughlin RC. Review article: the long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;22:55–63. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang Y-X. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: expert review and best practice advice from the American gastroenterological association. Gastroenterology 2017;152:706–15. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarpignato C, Gatta L, Zullo A, et al. . Effective and safe proton pump inhibitor therapy in acid-related diseases – a position paper addressing benefits and potential harms of acid suppression. BMC Med 2016;14:179 10.1186/s12916-016-0718-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. . Systematic review or scoping review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. . PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, et al. . Comparison of outcomes twelve years after antireflux surgery or omeprazole maintenance therapy for reflux esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:1292–8. 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundell L, Vieth M, Gibson F, et al. . Systematic review: the effects of long-term proton pump inhibitor use on serum gastrin levels and gastric histology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:649–63. 10.1111/apt.13324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandil TS, Mousa AA, El-Gendy AA, et al. . The potential therapeutic effect of melatonin in gastro-esophageal reflux disease. BMC Gastroenterol 2010;10:7 10.1186/1471-230X-10-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Usai P, Manca R, Cuomo R, et al. . Effect of gluten-free diet on preventing recurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease-related symptoms in adult celiac patients with nonerosive reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:1368–72. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05507.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poh CH, Hershcovici T, Gasiorowska A, et al. . The effect of antireflux treatment on patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease undergoing a mental arithmetic stressor. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;23:e489–96. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01691.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:308–28. 10.1038/ajg.2012.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pottegård A, Broe A, Hallas J, et al. . Use of proton-pump inhibitors among adults: a Danish nationwide drug utilization study. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2016;9:671–8. 10.1177/1756283X16650156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Revaiah PC, Kochhar R, Rana SV, et al. . Risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients receiving proton pump inhibitors versus proton pump inhibitors plus prokinetics. JGH Open 2018;2:47–53. 10.1002/jgh3.12045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torvinen-Kiiskinen S, Tolppanen A-M, Koponen M, et al. . Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of hip fractures among community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer's disease-a nested case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:1135–42. 10.1111/apt.14589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biyik M, Solak Y, Ucar R, et al. . Hypomagnesemia among outpatient long-term proton pump inhibitor users. Am J Ther 2017;24:e52–5. 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahari K, Haruma K, Ohtani H, et al. . Proton pump inhibitor induction of gastric Cobblestone-like lesions in the stomach. Intern Med 2017;56:2699–703. 10.2169/internalmedicine.7964-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lochhead P, Hagan K, Joshi AD, et al. . Association between proton pump inhibitor use and cognitive function in women. Gastroenterology 2017;153:971–9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kearns MD, Boursi B, Yang Y-X. Proton pump inhibitors on pancreatic cancer risk and survival. Cancer Epidemiol 2017;46:80–4. 10.1016/j.canep.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Targownik LE, Goertzen AL, Luo Y, et al. . Long-Term proton pump inhibitor use is not associated with changes in bone strength and structure. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:95–101. 10.1038/ajg.2016.481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bahtiri E, Islami H, Hoxha R, et al. . Proton pump inhibitor use for 12 months is not associated with changes in serum magnesium levels: a prospective open label comparative study. Turk J Gastroenterol 2017;28:104–9. 10.5152/tjg.2016.0284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang K-W, Kuan Y-C, Luo J-C, et al. . Impact of long-term gastric acid suppression on spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with advanced decompensated liver cirrhosis. Eur J Intern Med 2016;32:91–5. 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeda Y, Doyama H, Tsuji K, et al. . Does long-term use of proton pump inhibitors cause hypomagnesaemia in Japanese outpatients? BMJ Open Gastroenterology 2014;1:e000003 10.1136/bmjgast-2014-000003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song H, Zhu J, Lu D. Long-Term proton pump inhibitor (PPi) use and the development of gastric pre-malignant lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;35:Cd010623. 10.1002/14651858.CD010623.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis JR, Barre D, Zhu K, et al. . Long-Term proton pump inhibitor therapy and falls and fractures in elderly women: a prospective cohort study. J Bone Miner Res 2014;29:2489–97. 10.1002/jbmr.2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Helgadóttir H, Metz DC, Yang Y-X, et al. . The effects of long-term therapy with proton pump inhibitors on meal stimulated gastrin. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46:125–30. 10.1016/j.dld.2013.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bektaş M, Saraç N, Cetinkaya H, et al. . Effects of Helicobacter pylori infection and long-term proton pump inhibitor use on enterochromaffin-like cells. Ann Gastroenterol 2012;25:123–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pregun I, Herszényi L, Juhász M, et al. . Effect of proton-pump inhibitor therapy on serum chromogranin A level. Digestion 2011;84:22–8. 10.1159/000321535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarzynski E, Puttarajappa C, Xie Y, et al. . Association between proton pump inhibitor use and anemia: a retrospective cohort study. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2349–53. 10.1007/s10620-011-1589-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujimoto K, Hongo M, The Maintenance Study Group . Safety and efficacy of long-term maintenance therapy with oral dose of rabeprazole 10 Mg once daily in Japanese patients with reflux esophagitis. Intern Med 2011;50:179–88. 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lombardo L, Foti M, Ruggia O, et al. . Increased incidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth during proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:504–8. 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshikawa I, Nagato M, Yamasaki M, et al. . Long-Term treatment with proton pump inhibitor is associated with undesired weight gain. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4794–8. 10.3748/wjg.15.4794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ally MR, Veerappan GR, Maydonovitch CL, et al. . Chronic proton pump inhibitor therapy associated with increased development of fundic gland polyps. Dig Dis Sci 2009;54:2617–22. 10.1007/s10620-009-0993-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Soest EM, van Rossum LGM, Dieleman JP, et al. . Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:966–73. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01665.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashimoto H, Kushikata T, Kudo M, et al. . Does long-term medication with a proton pump inhibitor induce a tolerance to H2 receptor antagonist? J Gastroenterol 2007;42:275–8. 10.1007/s00535-006-1946-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Y–X, Hennessy S, Propert K, et al. . Chronic proton pump inhibitor therapy and the risk of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2007;133:748–54. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson DJ, Larsson H, Friis S, et al. . Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of colorectal cancer: a population-based, Case–Control study. Gastroenterology 2007;133:755–60. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Wesseling J, et al. . Increased risk of fundic gland polyps during long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:1341–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hritz I, Herszenyi L, Molnar B, et al. . Long-Term omeprazole and esomeprazole treatment does not significantly increase gastric epithelial cell proliferation and epithelial growth factor receptor expression and has no effect on apoptosis and p53 expression. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:4721–6. 10.3748/wjg.v11.i30.4721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiso M, Ito M, Boda T, et al. . Endoscopic findings of the gastric mucosa during long-term use of proton pump inhibitor - a multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2017;52:828–32. 10.1080/00365521.2017.1322137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Funaki Y, Kaneko H, Kawamura Y, et al. . Impact of comorbid irritable bowel syndrome on treatment outcome in non-erosive reflux disease on long-term proton pump inhibitor in Japan. Digestion 2017;96:39–45. 10.1159/000477801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatlebakk JG, Zerbib F, Bruley des Varannes S, et al. . Gastroesophageal acid reflux control 5 years after antireflux surgery, compared with long-term esomeprazole therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:678–85. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoon SB, Park JM, Lee J-Y, et al. . Long-term pretreatment with proton pump inhibitor and Helicobacter pylori eradication rates. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:1061–6. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i4.1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Labenz J, Armstrong D, Zetterstrand S, et al. . Clinical trial: factors associated with freedom from relapse of heartburn in patients with healed reflux oesophagitis - results from the maintenance phase of the EXPO study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:1165–71. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03990.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugano K, Kinoshita Y, Miwa H, et al. . Safety and efficacy of long-term esomeprazole 20 mg in Japanese patients with a history of peptic ulcer receiving daily non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. BMC Gastroenterol 2013;13:54 10.1186/1471-230X-13-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujimoto K, Hongo M. Risk factors for relapse of erosive GERD during long-term maintenance treatment with proton pump inhibitor: a prospective multicenter study in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2010;45:1193–200. 10.1007/s00535-010-0276-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mason JM, Raghunath AS, Hungin APS, et al. . Helicobacter pylori eradication in long-term proton pump inhibitor users is highly cost-effective: economic analysis of the HELPUP trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:1297–303. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03851.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hungin AP, Rubin GP, O'Flanagan H. Long-Term prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:451–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raghunath AS, Hungin APS, Mason J, et al. . Symptoms in patients on long-term proton pump inhibitors: prevalence and predictors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:431–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03897.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frazzoni M, Manno M, De Micheli E, et al. . Efficacy in intra-oesophageal acid suppression may decrease after 2-year continuous treatment with proton pump inhibitors. Dig Liver Dis 2007;39:415–21. 10.1016/j.dld.2007.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pezeshkian S, Conway SE. Proton pump inhibitor use in older adults: long-term risks and steps for deprescribing. Consult Pharm 2018;33:497–503. 10.4140/TCP.n.2018.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boghossian TA, Rashid FJ, Thompson W, et al. . Deprescribing versus continuation of chronic proton pump inhibitor use in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3:Cd011969. 10.1002/14651858.CD011969.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh K, Kwan D, Marr P, et al. . Deprescribing in a family health team: a study of chronic proton pump inhibitor use. J Prim Health Care 2016;8:164–71. 10.1071/HC15946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Velden AW, de Wit NJ, Quartero AO, et al. . Patient selection for therapy reduction after long-term daily proton pump inhibitor treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: trial and error. Digestion 2013;87:85–90. 10.1159/000345144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bjornsson E, Abrahamsson H, Simren M, et al. . Discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors in patients on long-term therapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:945–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03084.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krol N, Wensing M, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, et al. . Patient-directed strategy to reduce prescribing for patients with dyspepsia in general practice: a randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:917–22. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01928.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Othman F, Card TR, Crooks CJ. Proton pump inhibitor prescribing patterns in the UK: a primary care database study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016;25:1079–87. 10.1002/pds.4043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lødrup A, Reimer C, Bytzer P. Use of antacids, alginates and proton pump inhibitors: a survey of the general Danish population using an Internet panel. Scand J Gastroenterol 2014;49:1044–50. 10.3109/00365521.2014.923504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haroon M, Yasin F, Gardezi SKM, et al. . Inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors among medical inpatients: a questionnaire-based observational study. JRSM Short Rep 2013;4:2042533313497183. 10.1177/2042533313497183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Imfeld P, Bodmer M, Jick SS, et al. . Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Developing Alzheimer’s Disease or Vascular Dementia: A Case–Control Analysis. Drug Safety 2018;41:1387–96. 10.1007/s40264-018-0704-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shao Y-HJ, Chan T-S, Tsai K, et al. . Association between proton pump inhibitors and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:460–8. 10.1111/apt.14835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sieczkowska A, Landowski P, Gibas A, et al. . Long-Term proton pump inhibitor therapy leads to small bowel bacterial overgrowth as determined by breath hydrogen and methane excretion. J Breath Res 2018;12:036006 10.1088/1752-7163/aa9dcf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chien L-N, Huang Y-J, Shao Y-HJ, et al. . Proton pump inhibitors and risk of periampullary cancers--A nested case-control study. Int J Cancer 2016;138:1401–9. 10.1002/ijc.29896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clooney AG, Bernstein CN, Leslie WD, et al. . A comparison of the gut microbiome between long-term users and non-users of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;43:974–84. 10.1111/apt.13568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.den Elzen WPJ, Groeneveld Y, de Ruijter W, et al. . Long-Term use of proton pump inhibitors and vitamin B12 status in elderly individuals. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:491–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03601.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reimer C, Bytzer P. Discontinuation of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care patients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in patients with symptom relapse. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;22:1182–8. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32833d56d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]