Summary

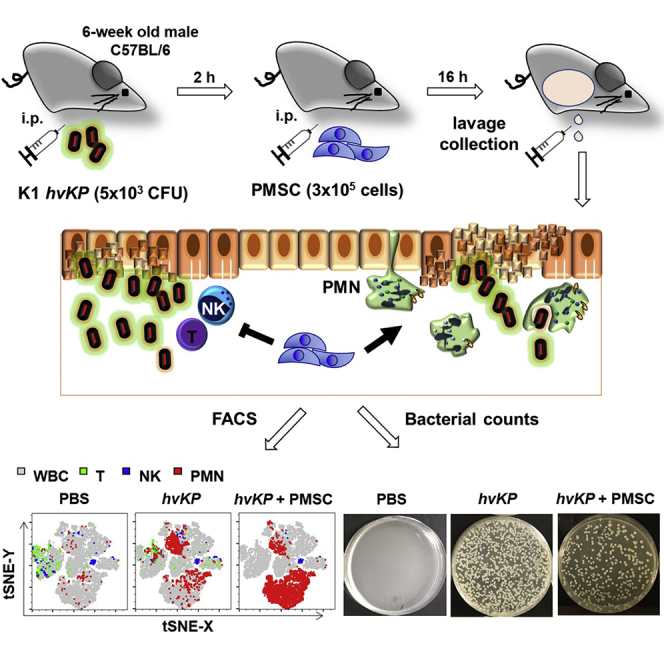

Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKP) strains cause extra-pulmonary infections such as intra-abdominal infection (IAI) even in healthy individuals due to its resistance to polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) killing and a high incidence of multidrug resistance. To assess whether human placental mesenchymal stem cell (PMSC) therapy can be an effective treatment option, we established a murine model of hvKP-IAI to evaluate immune cell modulation and bacterial clearance for this highly lethal infection. This protocol can rapidly assess potential therapies for severe bacterial IAIs.

For complete details on the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Wang et al. (2020).

Subject areas: Flow cytometry/mass cytometry, Immunology, Model organisms, Stem cells

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

PMSC treatment in a mouse model of hvKP-induced intra-abdominal infection

-

•

Isolation of mouse peritoneal immune cells without affixing mice to a dissecting board

-

•

Analysis of PMN, T, and NK cells in peritoneal washings

-

•

Determination of bacterial CFUs in hvKP-infected peritoneal fluid

Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKP) strains cause extra-pulmonary infections such as intra-abdominal infection (IAI) even in healthy individuals due to its resistance to polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) killing and a high incidence of multidrug resistance. To assess whether human placental mesenchymal stem cell (PMSC) therapy can be an effective treatment option, we established a murine model of hvKP-IAI to evaluate immune cell modulation and bacterial clearance for this highly lethal infection. This protocol can rapidly assess potential therapies for severe bacterial IAIs.

Before you begin

Antibody mix preparation

Timing: 30 min

-

1.

Prepare staining buffer: PBS solution with 2% heat-inactivated FBS

-

2.

Make an antibody mix in staining buffer per sample as below, and the volume for each sample is 50 μL.

| Fluorophore | Marker | Company | Cat# | Clone | Final dilution | Volume (μL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC-Cy7 | CD45 | BioLegend | 103116 | 30-F11 | 1:200 | 0.25 |

| BV421 | Ly6G | BioLegend | 127628 | 1A8 | 1:200 | 0.25 |

| PerCP | CD3 | BioLegend | 100326 | 145-2C11 | 1:100 | 0.5 |

| PE | NK1.1 | BioLegend | 108708 | PK136 | 1:100 | 0.5 |

| Staining buffer | 48.5 | |||||

| Total | 50 | |||||

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse CD3-PerCP | BioLegend | Cat # 100326; RRID: AB_893319 |

| Mouse CD45-APC-Cy7 | BioLegend | Cat # 103116; RRID: AB_312981 |

| Mouse NK1.1-PE | BioLegend | Cat # 108708; RRID: AB_313395 |

| Mouse Ly6G-BV421 | BioLegend | Cat # 127628; RRID: AB_256256 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Tsai et al., 2014 | Klebsiella pneumoniae NVT1001, capsular serotype 1 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| LB broth | Alpha Biosciences | Cat # L12-112; |

| Agar | Gene Teks | GT-PA001 |

| DMEM-low glucose | GIBCO-Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#11885076 |

| FBS | Hyclone-Thermo Fisher Scientific | SH30406.02 |

| Penicillin streptomycin | GIBCO-Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#15140122 |

| L-Glutamine | GIBCO-Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A2916801 |

| 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA | GIBCO-Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#25200072 |

| PBS pH 7.4 (1×) | GIBCO-Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#10010023 |

| Fixation Buffer | eBioscience-Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 00822249 |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Primary human placental mesenchymal stem cells (PMSCs) | Yen et al., 2005 | n/a |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6JNarI | National Laboratory Animal Center | RMRC11005 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FlowJo 10.6.0 | FlowJo, LLC-BD Biosciences | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

∗Alternative antibodies can be obtained from other manufacturers if generated from the same clones (i.e., from eBioscience).

CRITICAL: Cell culture reagents should not be substituted with products from other manufacturers, since PMSCs are primary cells and require very specific conditions for optimal growth and function.

Materials and equipment

LB broth

| Reagent | Final concentration (mM or μM) | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| LB broth | n/a | 25 g |

| ddH2O | n/a | 1 L |

| Total | n/a | 1 L |

LB broth was autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min and cooled down for culturing hvKP.

LB agar plate

| Reagent | Final concentration (mM or μM) | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| LB broth | n/a | 25 g |

| LB agar | 1.6% | 16 g |

| ddH2O | n/a | 1 L |

| Total | n/a | 1 L |

LB agar solution was autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min, and then prepared for each bacterial culture plate with 20 mL LB agar solution.

MSC culture medium

| Reagent | Final concentration (mM or μM) | Amount (mL) |

|---|---|---|

| DMEM-low glucose | n/a | 440 |

| FBS (vol/vol) | 10% | 50 |

| Penicillin streptomycin (10,000 U/mL) | 100 U/mL | 5 |

| L-Glutamine (200 mM) | 2 mM | 5 |

| Total | n/a | 500 |

Step-by-step method details

HvKP inocula preparation and inoculation at hour 0

Timing: 21 h

This step details amplification of HvKP for injection and induction of IAI in mice (Wang et al., 2020).

-

1.

Recover the clinical hvKP NVT1001 strain of serotype K1, which was previously isolated from a patient with liver abscess and stored at −80°C, in 20 mL LB broth for 16 h at 37°C.

-

2.

Dilute the cultured bacteria at 1: 10 with LB broth and keep the bacteria diluent cultured for additional 4 h at 37°C to maintain it in the logarithmic phase of growth.

-

3.

Adjust the bacteria solution to an optical density of 0.9 at 600 nm (around 4 × 108 colony-forming unit (CFU)/mL based on a previous report of this strain of hvKP (Tsai et al., 2014)) with a spectrophotometer.

-

4.

Bacteria were then diluted to a number of 5 × 104 CFU/mL in sterile PBS and maintained on ice until intraperitoneal inoculation. A lethal dose of 5 × 103 CFUs/100 μL which would cause near-absolute lethality within one week was intraperitoneally injected into 6-week old C57BL/6 male mice.

CRITICAL: Since bacteria harbor a very short life cycle of approximately 2 h, it is critical to have an accurate CFU number by adjusting bacteria solution to the suggested optical density and diluting it to the working concentration as soon as possible.

Human placental MSC (PMSC) preparation and injection at hour 2

Timing: 6 days

This step details expansion of human PMSCs for treatment of mice with hvKP-IAI.

-

5.Subculture of human PMSCs (Yen et al., 2005)

-

a.Thaw frozen PMSCs: 1 × 106 cells/mL per vial stored in vapor phase liquid nitrogen of approximately −196°C.

-

i.Prepare 9 mL pre-warmed MSC culture medium.

-

ii.Thaw frozen cells rapidly within 1 min in a 37°C water bath.

-

iii.Add 1 mL of thawed cells into pre-warmed MSC culture medium and collect PMSCs with centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature.

-

iv.Wash PMSCs with 10 mL pre-warmed PBS, centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature. Repeat this step twice.

-

v.Re-suspend the cells in 10 mL pre-warmed MSC culture medium and evenly seed the cells in a 75T flask.

-

vi.Maintain the cells in a 37°C incubator with humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 1 day.

-

vii.Replace with 10 mL fresh pre-warmed MSC culture medium.

-

viii.Culture the cells for another 2 days.

-

i.

-

b.Assess PMSC cultures: density reaching to more than 80% confluence which has at least 2 × 106 PMSCs in 75T flask.

-

c.Harvest PMSCs.

-

i.Remove spent medium.

-

ii.Wash cells twice with 10 mL pre-warmed PBS.

-

iii.Pipette 1 mL 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA onto PMSC monolayer.

-

iv.Rinse throughout the cells.

-

v.Pat the side of 75T flask for 1 min at room temperature.

-

vi.Examine cells: detaching cells to single cell suspensions.

-

vii.Pipette 9 mL pre-warmed MSC culture medium to neutralize Trypsin activity.

-

viii.Collect PMSC suspensions in a 50 mL centrifuge tube with centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature.

-

i.

-

d.Re-suspend PMSCs in 30 mL fresh MSC culture medium for each 75T flask with 10 mL of PMSC suspensions at a dilution of 1:3.

-

e.Culture PMSCs for 3 days

-

a.

-

6.Preparation of PMSCs for intraperitoneal injection

-

a.Harvest PMSCs.

-

i.Remove spent medium.

-

ii.Wash cells twice with 10 mL pre-warmed PBS.

-

iii.Pipette 1 mL 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA onto PMSC monolayer.

-

iv.Rinse throughout the cells.

-

v.Pat the side of 75T flask for 1 min at room temperature.

-

vi.Examine cells: detaching cells to single cell suspensions.

-

vii.Pipette 9 mL pre-warmed MSC culture medium to neutralize Trypsin activity.

-

viii.Collect PMSC suspensions in a 50 mL centrifuge tube with centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature.

-

i.

-

b.Wash PMSCs with 10 mL pre-warmed PBS, centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature. Repeat this step twice.

-

c.Re-suspend the cells in cold PBS and calculate the numbers of live PMSCs by trypan blue dye exclusion method with Neubauer chamber. Finally re-suspend PMSCs in cold PBS at a final concentration of 3 × 106/mL.

-

d.Keep the PMSC suspensions on ice until intraperitoneal injection. Then inject 3 × 105/100 μL of PMSCs intraperitoneally into control or infected mice.

-

a.

CRITICAL: To ensure viability and functional activity of PMSCs, it is critical to collect the cells within 1 min after trypsinization at room temperature. To have consistent results, we suggest that PMSCs are cultured for 3 days after subculture with 1: 3 split to obtain at least 2 × 106 cells for harvest in each experiment.

Isolation of peritoneal cavity cells at hour 18

Timing: 30 min

This step details isolation of mouse peritoneal immune cells without needing to affix the mice to a dissecting board or aspirating with a syringe within the peritoneal cavity 18 h after initial hvKP inoculation (or 16 h after PMSC treatment) (Figure 1)

-

7.

Euthanize a mouse with CO2 inhalation, a commonly used method to sacrifice laboratory animals, with 30% cage volume/min for one min and spray the mouse with 70% ethanol (Figure 1A). Other methods for animal euthanasia in this experiment can be used but should be tested to ascertain to have minimal effects on immune cell activity.

-

8.

Use scissors and one tissue forceps to transversely cut the skin on the lower abdomen (Figure 1B).

-

9.

Cut the skin longitudinally along the anterior median line (Figure 1C).

-

10.

Remove the ventral skin (Figure 1D).

-

11.

Spray the peritoneum with 70% ethanol (Figure 1E).

-

12.

Wipe the peritoneum with a paper towel (Figure 1F).

-

13.

Use tissue forceps to lift up the peritoneum (Figure 1G).

-

14.

Inject 10 mL of cold PBS into the peritoneal cavity using a 27G needle (Figure 1H). Avoid perforating any organs.

-

15.

Hold both sides of removed skin to gently shake the mouse for 1 min to allow injected PBS to circulate within the peritoneal cavity (Figure 1I).

-

16.

Tent and distend the abdomen by holding the mice from the back and tightening skin folds bilaterally, then use a 27G needle to puncture into the peritoneum (Figure 1J). Avoid perforating any organs.

-

17.

Squeeze out as much PBS-containing peritoneal fluid as possible through punctured site into a 10-cm dish (Figure 1K).

-

18.

Collect the peritoneal washings (Figure 1L) and keep on ice until processing.

CRITICAL: It is critical to use only sterile equipment and sterile materials, and harvest peritoneal washings without touching the removed skin to prevent contamination with normal skin flora interfering in the following hvKP CFU counting assay.

Figure 1.

Isolation of mouse peritoneal immune cells without needing to affix the mice to a dissecting board or aspirating with a syringe within the peritoneal cavity

(A) Euthanize a mouse with CO2 inhalation and spray the mouse with 70% ethanol.

(B) Use scissors and one tissue forceps to transversely cut the skin on the lower abdomen.

(C) Cut the skin longitudinally along the anterior median line.

(D) Remove the ventral skin.

(E) Spray the peritoneum with 70% ethanol.

(F) Wipe the peritoneum with a paper towel.

(G) Use tissue forceps to lift up the peritoneum.

(H) Inject 10 mL of cold PBS into the peritoneal cavity using a 27G needle.

(I) Gently shake the mouse for 1 min to wash the peritoneal cavity.

(J) Tent and distend the abdomen by holding the mouse from the back and tightening skin folds bilaterally, then use a 27G needle to puncture into the peritoneum.

(K) Squeeze out as much PBS-containing peritoneal fluid as possible through punctured site.

(L) Collect the peritoneal washings (approximately 8 mL).

Staining of peritoneal cavity cells for flow cytometric analyses

Timing: 2 h

This step details staining of cells collected from peritoneal washings for flow cytometric analysis of PMN, T and NK cells using V-bottom 9-well microplate (Bingham et al., 2015; Lehmann et al., 2017).

-

19.Cell preparation

-

a.Calculate live cells by trypan blue dye exclusion method with Neubauer chamber: approximately 8 × 106 peritoneal cavity cells can be harvested from each control animal while more than 5 × 107 cells can be collected from each hvKP-infected animal.

-

b.Transfer 2 × 105 peritoneal cavity cells per well into V-bottom 96-well microplate.

-

c.Pellet cells by centrifuging at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

-

d.Remove supernatant by flicking liquid within the well plate into the sink (Cells will be kept in the bottom of each well in the V-plate).

-

e.Re-suspend cells with 200 μL cold PBS.

-

f.Pellet cells by centrifuging at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

-

g.Remove supernatant by flicking liquid within the well plate into the sink.

-

a.

-

20.Surface staining

-

a.Re-suspend cells with 200 μL staining buffer at room temperature for 10 min to prevent non-specific binding.

-

b.Pellet cells by centrifuging at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

-

c.Remove supernatant by flicking liquid within the well plate into the sink.

-

d.Re-suspend cells with 50 μL staining buffer with antibody mix. Single fluorescent marker of each fluorophore is also prepared for compensation controls using pooled samples from control and infected mice.

-

e.Incubate at 4°C for 30 min in the dark.

-

f.Pellet cells by centrifuging at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

-

g.Remove supernatant by flicking liquid within the well plate into the sink.

-

h.Wash cells twice with 200 μL cold PBS.

-

i.Remove supernatant by flicking liquid within the well plate into the sink.

-

a.

-

21.Fixation of antibody

-

a.Re-suspend cells with 100 μL fixation buffer for 10 min.

-

b.Pellet cells by centrifuging at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

-

c.Remove supernatant by flicking liquid within the well plate into the sink.

-

d.Re-suspend cells with 200 μL PBS.

-

e.Keep samples in the dark at 4°C until data collection.

-

a.

CRITICAL: It is critical to perform red blood cell lysis before step 19a if inadvertent contamination occurs during the process of collecting peritoneal lavage. (see Troubleshooting 2)

Collection of flow cytometric data

Timing: 1.5 h

The step details flow cytometric data acquisition using BD FACSVerse flow cytometer according to published protocols (Maecker and Trotter, 2006).

-

22.Condition setting at low (12 μL/min) flow rate

-

a.Unstained sample was applied to set appropriate PMT voltages to identify immune cells in forward versus side scatter (FSC versus SSC) gating first, and then by adjusting the logarithmic scale of each fluorescence channel to baseline levels.

-

b.Single stained samples of each fluorophore were applied to set appropriate compensation condition to correct the signals of inherent fluorescence spillover.

-

a.

-

23.Data collection and analysis

-

a.Deliver the plate or tube racks with 2 × 105 peritoneal cavity cells/200 μL PBS/sample to the BD FACSVerse system for acquisition at high (120 μL/min) flow rate.

-

b.Perform the analyses with gating for CD45 first and then CD3, NK1.1, or Ly6G.

-

a.

CRITICAL: It is critical to adjust PMT voltage gains first using an unstained sample, and then correct for fluorescence spillover using compensation controls since the PMT voltage is correlated with the degree of compensation. For flow cytometric analyses, it is possible to use older equipment such as FACSCalibur.

Measurement of bacterial load

Timing: 18 h

This step details bacterial plating of peritoneal lavage fluid on LB agar plates for quantification of bacterial CFUs (Sutherland et al., 2008).

-

24.

Make 1:10 serial dilutions of each sample (50 μL into 450 μL cold PBS).

-

25.

Spread 100 μL of each dilution onto LB agar plates.

-

26.

Incubate plates at 37°C for 16 h.

-

27.

Count the number of CFU for all dilutions of each sample.

CRITICAL: It is critical to keep all samples on ice to minimize hvKP growth until plating on LB agar plates.

Expected outcomes

Following the protocol, we established a murine model of hvKP-IAI and also assessed the therapeutic efficacy of PMSC treatment which was via modulation of immune cells and enhancing bacterial clearance. To identify different immune cell populations, we first gated for lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes on the FSC versus SSC dot plot based on classical criteria for each cell type using a control sample and then with hvKP-challenged as well as PMSC treatment samples. To assess the changes in immune cell populations after hvKP infection and PMSC treatment, we analyzed the profile of granule contents in leukocytes and gated CD45+ cells on the CD45 versus Ly6G dot plot in both control and hvKP-challenged samples. To specifically determine the effect of PMSCs on lymphoid cells and granulocytes in hvKP-challenged animals, we analyzed and compared the frequencies of T and PMN cells using dot plots of CD3 versus Ly6G, or NK and PMN cells using dot plots of NK1.1 versus Ly6G dot plots, in CD45+ gated populations of both control and hvKP-challenged samples, which demonstrated PMSC immunomodulation of T and NK cells but enhancement of PMN activation against hvKP infection (Figure 2). Peritoneal washings were plated on LB agar plate overnight for measurement of CFUs of hvKP, which demonstrated the therapeutic role of PMSCs in bacterial clearance (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Gating strategy for T, NK, and PMN analyses by flow cytometry

(A) Lymphocyte, monocyte, and PMN cells were first gated in FSC versus SSC plot.

(B) CD45+ cells were gated in CD45 versus Ly6G plot, showing a different profile of Ly6G+ population among PBS control group and hvKP groups with or without PMSC treatment.

(C) T cell versus PMN was showed in CD3 versus Ly6G plot.

(D) NK cell versus PMN was shown in NK1.1 versus Ly6G plot.

Figure 3.

Quantification of bacterial CFUs

This protocol also provides a convenient methodology to harvest peritoneal cavity cells without having to affix the mouse. Additionally, peritoneal lavage washings are collected through a punctured site rather than inserting a syringe into the cavity, which may inadvertently injure surrounding tissues/organs as well as contaminate collected fluid.

Our protocol provides a robust and rapidly progressive disease model of IAI, which has been reported to be caused by multidrug-resistant (Paczosa and Mecsas, 2016; Paterson et al., 2004) and/or phagocytosis-resistant KP strains such as the K1 serotype used in this study (Lin et al., 2004). This protocol therefore can be very useful to uncover the mechanism underlying hvKP pathogenesis and identify therapeutic options for clinical use. Moreover, the protocol can likely be adapted to study MSC or other therapies for other microorganisms which cause severe, lethal abdominal infections—such as Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, and other Enterobacteriaceae (Thadepalli et al., 2004; Wiest et al., 2012)—to induce absolute lethality rapidly within days to weeks based on CFU doses specifically determined for each microorganism.

Limitations

The high lethality of this hvKP strain—which has a LD50 of only 200 CFUs (Tsai et al., 2014)—has meant that titrations of bacterial counts for in vivo experiments (which require dilution, transfer, and injection) can be accompanied with some variability. Although differences within ±1,000 counts of bacteria or a 5-fold range are acceptable parameters set by the field (Anderegg et al., 2004), care must be taken to not infect mice with greater than 5 × 103 CFUs of hvKP to avoid rapid and near immediate death (within 1–2 days) in the entire inoculated cohort.

PMN cells have very short half lives in vivo and therefore are difficult to remain viable in in vitro culture (Manz and Boettcher, 2014; Tak et al., 2013). This may produce a wider range of experimental results compared to experiments performed using other immune cells with longer in vivo half lives.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

Stability of human PMSC functional effects.

Potential solution

Human MSCs are primary cells with finite proliferative capacity, moreover, functional—including differentiation and immunomodulation ability—and proliferative capacity of primary human samples/cells vary from donor to donor. Moreover, all primary cells will undergo replicative senescence in in vitro culture, which in stem cells has been reported to detrimentally affect functional capacity (Ho et al., 2013; Rossi et al., 2005). Therefore, it is important to utilize PMSCs prior to succumbing to replicative senescence, which can be observed by a slowing in doubling time and decreased cell yield as we have found previously (Ho et al., 2013).

Problem 2

Contamination of red blood cells during peritoneal lavage.

Potential solution

Red blood cell contamination in extracted cells can be lysed prior to step 19a using hypotonic buffer (H2O with 0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM Na2-EDTA) for 5 min and then washed with cold PBS.

Problem 3

Wide variability in the dose of inoculated hvKP between experiments.

Potential solution

The rapid proliferation of bacteria relative to experimental procedures may result in wide variability, so to ascertain the exact dose of bacteria inoculated into each mouse, therefore at the time of inoculating each mouse we also simultaneously inoculate a LB agar plate to check the precise CFU of bacteria actually injected and whether the variability was within field standards for each experiment. Since the dose variability is mainly due to rapid growth of the bacteria, one way to minimize this variability is to be strict and consistent in the timing of every step which involve working with bacteria. Also, the rapid lethality of LD100 disease models may require some titration of PMSC dose (i.e., additional injections) as has been done in clinical trials to achieve optimal therapeutic outcome.

Problem 4

Inability to accurately capture hvKP CFU counts after in vivo experiments.

Potential solution

The range of hvKP CFUs in infected mice with or without PMSC treatment can be quite different (106–1011 in infected mice without PMSC treatment, and 100–108 after PMSC treatment). To accurately capture bacterial CFUs in in vivo experiments, it may be necessary to serially dilute the peritoneal washings from each mouse and plate all dilutions on LB agar plates in order to capture as broad range of CFUs as possible (i.e., from 100 to 1010).

Problem 5

Cell viability of extracted murine peritoneal cell during ex vivo antibody staining for flow cytometric analysis.

Potential solution

While standard trypan blue dye exclusion method can be used to determine live cells for further staining procedures, if more time is needed during ex vivo antibody staining for flow cytometric analysis, a cell viability dye (i.e., 7-AAD) is recommended to gate for live cells and exclude inadvertent dead cells which may have occurred due to the time lag between extraction of peritoneal cells and flow cytometric analysis.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, B. Linju Yen (blyen@nhri.org.tw).

Materials availability

The clinical hvKP NVT1001 strain of serotype K1 used in this study can be made available upon request with a Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funding from NHRI (10A1-CSPP06-014 to B.L.Y.), the Ministry of National Defense ROC (MND-MAB-110-114 to S.K.C.), and the Taiwan Ministry of Science & Technology (MOST: MOST109-2326-B-002 -016 -MY3 to L.T.W., MOST107-2314-B-002-104-MY3 to M.L.Y., and MOST105-2628-B-400-007-MY3 to B.L.Y.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.Y. and B.L.Y.; Methodology, L.T.W., S.K.C., and W.L.; Investigation, L.T.W., S.K.C., and W.L.; Writing – Original Draft, L.T.W., M.L.Y., and B.L.Y.; Writing – Review and Editing, L.T.W., M.L.Y., and B.L.Y.; Funding Acquisition, M.L.Y. and B.L.Y.; Resources, L.K.S.; Supervision, M.L.Y. and B.L.Y.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Men-Luh Yen, Email: mlyen@ntu.edu.tw.

B. Linju Yen, Email: blyen@nhri.edu.tw.

References

- Anderegg T.R., Fritsche T.R., Jones R.N., Quality Control Working, G. Quality control guidelines for MIC susceptibility testing of omiganan pentahydrochloride (MBI 226), a novel antimicrobial peptide. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:1386–1387. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1386-1387.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham K.N., Lee M.D., Rawlings J.S. The use of flow cytometry to assess the state of chromatin in T cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2015:e53533. doi: 10.3791/53533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho P.J., Yen M.L., Tang B.C., Chen C.T., Yen B.L. H2O2 accumulation mediates differentiation capacity alteration, but not proliferative decline, in senescent human fetal mesenchymal stem cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;18:1895–1905. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J.S., Zhao A., Sun B., Jiang W., Ji S. Multiplex cytokine profiling of stimulated mouse splenocytes using a cytometric bead-based immunoassay platform. J. Vis. Exp. 2017:56440. doi: 10.3791/56440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.C., Chang F.Y., Fung C.P., Xu J.Z., Cheng H.P., Wang J.J., Huang L.Y., Siu L.K. High prevalence of phagocytic-resistant capsular serotypes of Klebsiella pneumoniae in liver abscess. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maecker H.T., Trotter J. Flow cytometry controls, instrument setup, and the determination of positivity. Cytometry A. 2006;69:1037–1042. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manz M.G., Boettcher S. Emergency granulopoiesis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:302–314. doi: 10.1038/nri3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paczosa M.K., Mecsas J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016;80:629–661. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00078-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson D.L., Ko W.C., Von Gottberg A., Mohapatra S., Casellas J.M., Goossens H., Mulazimoglu L., Trenholme G., Klugman K.P., Bonomo R.A. Antibiotic therapy for Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;39:31–37. doi: 10.1086/420816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D.J., Bryder D., Zahn J.M., Ahlenius H., Sonu R., Wagers A.J., Weissman I.L. Cell intrinsic alterations underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2005;102:9194–9199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503280102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland R.E., Olsen J.S., McKinstry A., Villalta S.A., Wolters P.J. Mast cell IL-6 improves survival from Klebsiella pneumonia and sepsis by enhancing neutrophil killing. J. Immunol. 2008;181:5598–5605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak T., Tesselaar K., Pillay J., Borghans J.A., Koenderman L. What's your age again? Determination of human neutrophil half-lives revisited. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013;94:595–601. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1112571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thadepalli H., Chuah S.K., Gollapudi S. Therapeutic efficacy of moxifloxacin, a new quinolone, in the treatment of experimental intra-abdominal abscesses induced by Bacteroides fragilis in mice. Chemotherapy. 2004;50:76–80. doi: 10.1159/000077806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y.K., Liou C.H., Lin J.C., Ma L., Fung C.P., Chang F.Y., Siu L.K. A suitable streptomycin-resistant mutant for constructing unmarked in-frame gene deletions using rpsL as a counter-selection marker. PLoS One. 2014;9:e109258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.T., Wang H.H., Chiang H.C., Huang L.Y., Chiu S.K., Siu L.K., Liu K.J., Yen M.L., Yen B.L. Human placental MSC-secreted IL-1beta enhances neutrophil bactericidal functions during hypervirulent Klebsiella infection. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108188. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiest R., Krag A., Gerbes A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: recent guidelines and beyond. Gut. 2012;61:297–310. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen B.L., Huang H.I., Chien C.C., Jui H.Y., Ko B.S., Yao M., Shun C.T., Yen M.L., Lee M.C., Chen Y.C. Isolation of multipotent cells from human term placenta. Stem Cells. 2005;23:3–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.