Introduction

Nivolumab is a human monoclonal antibody used to treat malignancies, including melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC).1 Nivolumab acts via inhibition of T-lymphocytes by targeting the programmed cell death-1 receptor.2 Despite the checkpoint inhibitor's success in treatment response, immunomodulatory therapies are not without risks, as programmed cell death-1 inhibition has led to immune-related cutaneous adverse events, including rash (14.3%), pruritus (13.2%), and, in severe cases (1.4%), Steven Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis.2

The onset of cutaneous lymphoma is one adverse event not previously described to date in the literature. This case study characterizes a patient with nivolumab-associated cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) in the setting of RCC.

Case report

A 53-year-old Caucasian man with a history of tobacco use presented to primary care following a back injury in September 2015. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine incidentally showed a left renal mass, prompting a computed tomography-guided needle biopsy demonstrating RCC. He underwent a left partial nephrectomy. The final pathology report showed a pT3N0M0, Furhman grade 4 clear cell RCC with sarcomatoid features, and a positive margin.

Post-operative staging computed tomography scans revealed bilateral pulmonary nodules prompting a suspicion of metastatic disease, and he commenced sunitinib monotherapy for advanced RCC.3 He was treated for 8 months until progression and began nivolumab second-line therapy in May 2017.

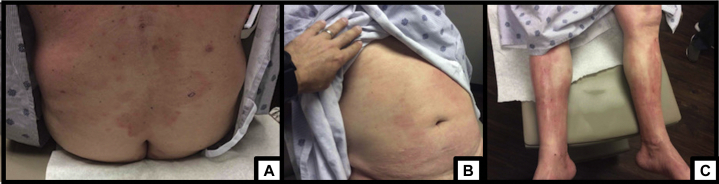

After 6 cycles of nivolumab, imaging demonstrated a complete response, and he continued treatment with disease control until May 2018, before cycle twenty-one. He reported fatigue and pruritus with the onset of a rash, unrelieved by hydration, emollients, and topical steroids. He had excoriations on the back, with erythematous patches on the left chest, and scattered, indurated areas on the chest, arms, and legs, covering over 50% body surface area (Fig 1). Nivolumab was held. He received systemic steroids and was referred to Dermatology.

Fig 1.

Patches of scattered, indurated, erythematous patches of CTCL on initial presentation. A, Lower back. B, Abdomen. C, Bilateral lower extremities. CTCL, Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

(Photos courtesy of Dr. Carmen Julian.)

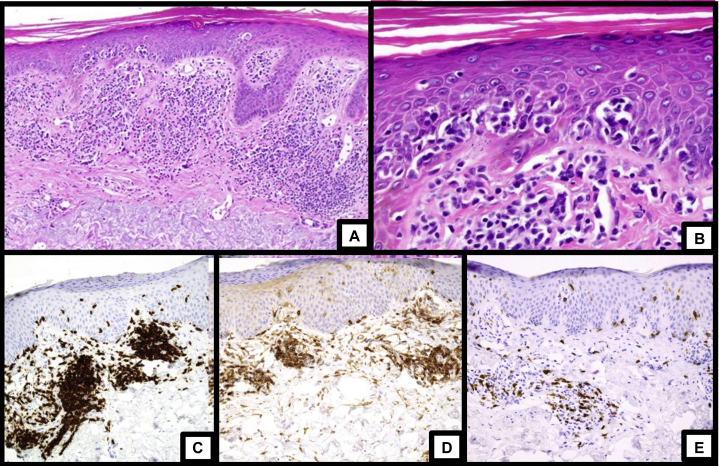

In July 2018, he underwent multiple skin biopsies, all of which revealed perivascular and band-like infiltrates of atypical lymphocytes with foci of epidermotropism (Fig 2). The atypical lymphocytes were strongly positive for CD3 and CD4 with an elevated CD4:CD8 ratio, reduction of CD7, and T-cell clonality via gene rearrangement studies, consistent with CTCL.

Fig 2.

Histopathologic images and immunohistochemistry of skin biopsies from the right leg and left arm. A, Low magnification showing a superficial lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism. B, High magnification showing atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis. C, Staining for CD3 showed diffuse positivity in the dermal and intraepidermal lymphocytes. D, Staining for CD4 showed that the majority of lymphocytes were CD4-positive. E, Staining for CD8 showed a minority population of CD8-positive lymphocytes.

(Photos and descriptions courtesy of Dr. Douglas Parker.)

On oncologic evaluation in October, he complained of persistent fatigue, excessive xeroderma, and pruritus associated with continued rash, skin discoloration of the fingers and toes, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. He was without B-symptoms or systemic symptoms. His exam was notable for diffuse lymphadenopathy and generalized erythroderma involving over 80% of his body with desquamation and hyperkeratosis.

T-cell gene rearrangement studies of the skin and blood had matching T-cell clones. Flow cytometry on peripheral blood revealed a T-cell clonal population of 7% with CD4+CD7- cells; CD26 expression was not detected. His white blood cell count was 8.7 × 109/L with a Sezary count of 609 cells/μL and lactate dehydrogenase within normal limits. He was diagnosed with cutaneous T cell lymphoma at clinical stage IIIB disease (T4NxB1) and was scheduled to start extracorporeal photopheresis and interferon with bexarotene treatment.

Unfortunately, his response to treatment was limited in the setting of nonadherence secondary to financial inequities. He was eventually able to obtain financial coverage of his treatment regimen in April 2019. His disease progressed to stage IVA1 disease (T4NxB2) with a white blood cell count of 21.1 × 109/L and a Sezary count of 11.8 cells/μL and extracorporeal photophoresis was added.4 He otherwise did not receive other systemic treatment except for suppressive doxycycline prophylaxis, gabapentin, clobetasol cream, Aquaphor/Cetaphil, and wet wraps.

Upon re-evaluation, he had minimal improvement despite therapy, and his erythroderma persisted, involving > 90% of body surface area with multiple bilateral excoriations of the upper extremities. Upon evaluation in September 2019, he had clinical improvement; however, he was lost to follow up and shortly expired from a disease-unrelated complication.

Discussion

Pharmacologic immunomodulators are becoming staples in managing solid and liquid malignancies.1 To our knowledge, this article is the first to describe the development of CTCL associated with nivolumab treatment for advanced RCC. Other immunomodulators, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, may similarly be implicated in the development of cutaneous lymphomas.5

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the mechanism of disease. Immunosuppressive therapies in the setting of chronic lymphocytic-inflammatory processes may facilitate the selection of malignant T-cell clones, leading to the development of CTCL.5 Previous research has shown that immunomodulators may accelerate previous low-grade primary cutaneous lymphomas or unmask lymphomas via downregulation of both innate and adaptive immunity, which regulate malignant cell proliferation.5 On the contrary, overactivation of the immune response may play a role, although autoantibodies are another potential mechanism of immunomodulation.1

Though the causality of nivolumab-associated CTCL remains elusive, paradoxically, checkpoint inhibitors, including nivolumab, may be an emerging treatment for relapsed or relapsed refractory T-cell lymphomas.6,7 Studies particularly on nivolumab are underway via phase Ib clinical trials; however, more recently, pembrolizumab has shown more promising results in similar patients in multicentered phase II trials.6,7 However, progression of T-cell lymphoma remains a concern with use of pembrolizumab in some cases via an unknown mechanism.6,7

Nonetheless, immune-related adverse events, including CTCL, remain a risk of immunotherapy.1,2 Expansion of the knowledge base of potential outcomes in the setting of immunomodulatory therapy, including CTCL, may help identify future patients and accelerate diagnosis at symptom onset.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

References

- 1.Bajwa R., Cheema A., Khan T. Adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors (programmed death-1 inhibitors and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 inhibitors): results of a retrospective study. J Clin Med Res. 2019;11:225–236. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Słowińska M., Maciąg A., Rozmus N., Paluchowska E., Owczarek W. Management of dermatological adverse events during nivolumab treatment. Oncol Clin Pract. 2017;13:301–307. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonasch E. NCCN guidelines updates: Management of metastatic kidney cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:587–589. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.5008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen E.A., Rook A.H., Zic J. Sézary syndrome: immunopathogenesis, literature review of therapeutic options, and recommendations for therapy by the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium (USCLC) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:352–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Escala M.E., Posligua A.L., Wickless H. Progression of undiagnosed cutaneous lymphoma after anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1068–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lesokhin A.M., Ansell S.M., Armand P. Nivolumab in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancy: preliminary results of a phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(23):2698–2704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.9789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khodadoust M.S., Rook A.H., Porcu P. Pembrolizumab in relapsed and refractory mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:20–28. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]