Abstract

Background:

GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction (GSZD), a traditional Chinese herbal medication, has been frequently used as an add-on medication to methotrexate (MTX) for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment in China. This meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy and safety of adding GSZD to MTX for RA treatment.

Methods:

We performed a systematic search of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library (all databases) for English-language studies and WanFang, VIP, and CNKI for Chinese-language studies up to 28 July 2020. Data from selected studies, mainly the response rates and rate of adverse events (AEs), were extracted independently by two authors, and a random-effects model (Mantel–Haenszel method) was used for the meta-analysis.

Results:

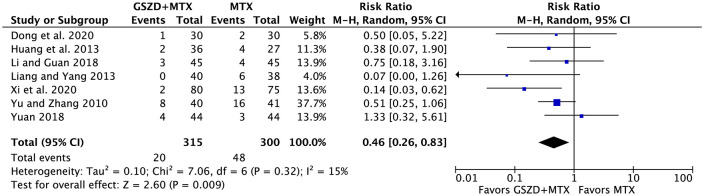

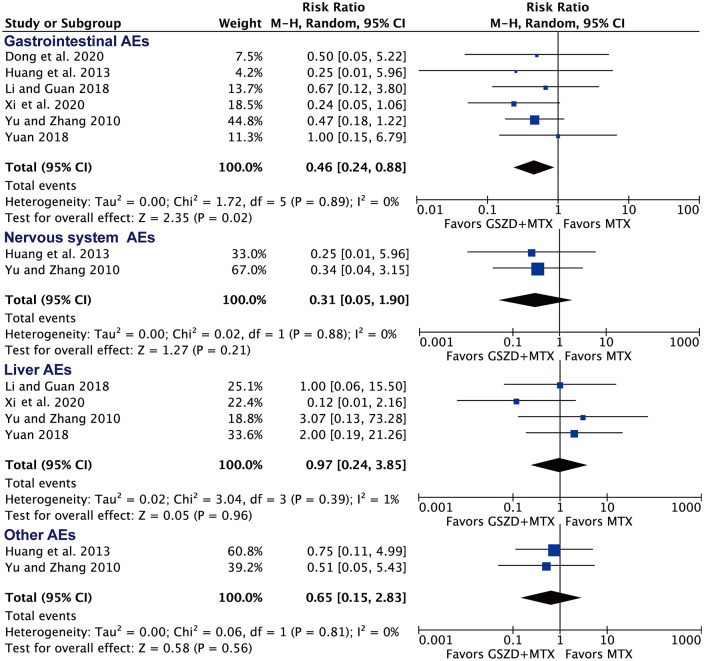

A total of 14 randomized controlled trials and 1224 patients were included (623 patients in the GSZD + MTX group and 601 patients in the MTX group). For efficacy, the meta-analysis found that combining GSZD with MTX increased the effective rate [relative risk (RR) = 1.24, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.18–1.30, based on 1069 patients], defined as >30% efficacy, American College of Rheumatology 20, or a decrease of disease activity score 28 >0.6. Adding GSZD reduced the swollen and tender joint counts, the duration of morning stiffness, the levels of C-reactive protein and rheumatoid factor, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The adjuvant therapeutic effect of GSZD was independent of the dose of MTX or the combined utilization of other drugs in both groups. For safety, adding GSZD was associated with a lower rate of total AEs (RR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.26–0.83, based on 615 patients) and gastrointestinal tract AEs (RR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.24–0.88, based on 537 patients).

Conclusion:

Combining GSZD with MTX may be a more efficacious and safer strategy for treating RA compared with MTX alone. Further large studies are warranted to investigate the long-term efficacy and safety of adding GSZD to MTX for RA treatment.

Keywords: meta-analysis, methotrexate, rheumatoid arthritis, traditional Chinese medication

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common chronic autoimmune disease characterized by systemic and synovial inflammation.1 RA affects 0.5–1.0% of the general population, especially women and the elderly.2 If not well controlled, RA may result in permanent joint damage and disability. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), glucocorticoids, and biologic agents may attenuate symptoms and prevent joint deformation.3 However, current pharmacologic therapies do not produce an adequate response in many patients and may also have long-term side effects.1 For example, only 30% of patients have low disease activity with the DMARD methotrexate (MTX) alone, which is an anchor drug for initial RA treatment but may also lead to many adverse effects.4,5 Combining MTX with other drugs, such as NSAIDs, steroids, or other DMARDs, could be used when RA cannot be well-controlled by MTX. However, the use of NSAIDs may be restricted because of the risk of gastrointestinal and cardiovascular toxicity during treatment;6,7 steroids and other DMARDs may also lead to side effects;8 and biologics may be too expensive.9 More importantly, using these combination therapies still does not produce an adequate response in many patients.10 Thus, new pharmacological strategies for RA treatment are still warranted.

GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction (GSZD), a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) herbal formula, has been used for RA treatment in China since the Han Dynasty. GSZD is composed of Cinnamomum cassia (L.) J.Presl (Gui Zhi, 12 g), Paeonia albiflora Pall. (Shao Yao, 9 g), Ephedra sinica Stapf. (Ma Huang, 12 g), Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge (Zhi Mu, 12 g), Radix Glycyrrhizae Preparata (Zhi Gan Cao, 6 g), Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk. (Fang Feng, 12 g), Aconitum carmichaeli var. carmichaeli (Fu Zi, 10 g), Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Sheng Jiang, 15 g), and Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. (Bai Zhu, 15 g).11 A previous general meta-analysis showed that GSZD may have equal or superior effectiveness and safety for treating RA compared with DMARDs.12 Recently, several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) indicated that combining GSZD with MTX may achieve better effectiveness than MTX in patients with RA. However, the evidence for GSZD as an add-on medication to MTX in RA remains inadequate. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to assess the efficacy and safety of combining GSZD with MTX for use in patients with RA.

Methods

Our study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.13

Protocol and registration

Our protocol has been submitted to PROSPERO, registered on 28 April 2020, and updated on 27 October 2020 (Protocol registration number: CRD42020151593). Ethical approval was not required as the current study was based on published data.

Data sources and literature search

We performed a systematic search of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library (all the databases in the Cochrane library) for English-language studies up to 28 July 2020 without limiting the beginning date. We also performed a systematic search of WanFang DATA (http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/), VIP (http://www.cqvip.com/), and the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) (http://www.cnki.net/) for Chinese-language studies. Details of our search strategy are shown in Supplemental material Tables 1–4 online for English-language studies and Supplemental Table 5 for Chinese-language studies. Additional studies were identified from published reviews and the reference lists of selected papers.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) the study must be a RCT; (2) patients must be diagnosed as having RA according to American College of Rheumatology (ACR) diagnostic criteria; (3) patients must have received intervention treatment with GSZD and MTX; (4) the study must include an ACR 20 or ACR 50 response rate, modified response rate based on ACR response criteria (such as 30% efficacy),14–16 or a decrease of disease activity score 28 (ΔDAS28)17 as the main outcome indicator.

Exclusion criteria: (1) the dose of MTX does not meet the ACR guidelines (such as 5 mg/day or 10 mg/day); (2) except for concurrent use of drugs, no other therapeutic factors, such as acupuncture, were used.

Study selection

Study selection was conducted based on the PRISMA flow diagram. The results of the literature search were imported into the software Endnote X9. Two reviewers (C.F. and R.C.) independently assessed the potentially eligible studies for inclusion. First, the titles and abstracts were screened to exclude the duplicated and other irrelevant studies according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Then, we re-screened the full-text of each potentially relevant article that was not excluded. Any discordances were resolved by a third investigator (Z. X.).

Data collection

Two reviewers (C.F. and R.C.) independently reviewed studies to extract potentially eligible studies and data. We mainly collected the response rates, RA related clinical symptoms and laboratory indexes, and adverse events (AEs) or side effects. When the results were inconsistent, the third investigator was responsible for reconciling (Z.X.).

Risk-of-bias assessments

To assess the risk of bias of included trials, we used the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Six domains of bias were assessed: (1) selection bias (randomization and allocation concealment); (2) performance bias (blinding of participants and investigators); (3) detection bias (blinding of outcome adjudicators); (4) attrition bias (differential loss to follow-up); (5) reporting bias (selective outcome reporting); and (6) other sources of bias. The risk of bias assessment was conducted by two independent reviewers, and discrepancies were resolved by the third investigator (Z.X.).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using Review Manager, version 5.3 (Nordic Cochrane Centre). Standardized mean differences were estimated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous outcomes, including tender joint counts (TJCs), swollen joint counts (SJCs), duration of morning stiffness (DMS), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and rheumatoid factor (RF). Relative risks (RRs) were estimated for dichotomous outcomes, including the response rates and rate of AEs. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by Cochran’s Q statistic and the I2 statistic. As the studies included in the analysis are not functionally identical and we wanted to compute the common effect size to generalize to other populations, a random-effects model (Mantel–Haenszel method) was employed for the meta-analysis. Subgroup meta-analyses were based on the dose of MTX and the additional drugs concurrently used in both groups. Begg’s funnel plots were generated for assessing publication bias when possible. In addition, to evaluate the strength and stability of the meta-analysis, sensitivity analysis was conducted by omitting the individual studies one by one. The sensitivity analysis was carried out for response rates, clinical symptoms and laboratory indexes, and the rate of AEs. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

RCT selection

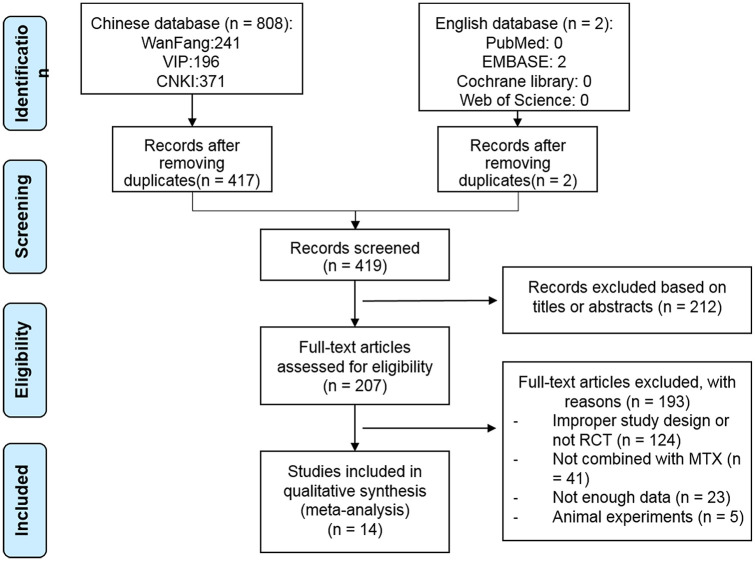

The study selection process is depicted in Figure 1. A total of 419 articles were extracted from the literature search for the initial assessment. In total, 212 articles were removed after reading the abstracts and 193 articles were removed after full-text assessment. Of note, three RCTs were excluded because they used GSZD monotherapy.18–20 Two RCTs were removed because of the excessive dose of MTX (5 mg/day for 12 weeks in Liu and Shi21 and 10 mg/day for 8 weeks in Liu et al.22). Finally, a total of 14 articles were included in the current meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

MTX, methotrexate; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CI, confidence interval; DAS28, Disease activity score 28; GSZD, GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction; MTX, methotrexate; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Characteristics and quality of the studies

All 14 RCTs used GSZD in the form of water decoction.23–36 The details of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Of note, four RCTs (Zhou et al.,23 Yuan,24 Zhang et al.,25 and Xi and Zhang26) did not additionally use any other drugs in both groups, For RCTs (Xiao,27 Ji,28 Cui,29 Li et al.30) used NSAIDs in both groups, two RCTs (Yu and Zhang,31 Li et al.32) used other DMARD (sulfasalazine) in both groups, three RCTs (Huang et al.,33 Liang and Yang,34 Dong35) used other DMARDs (sulfasalazine or leflunomide) plus NSAIDs (celecoxib or diclofenac sodium) in both groups and the other one RCT (Wu36) used other DMARD (sulfasalazine) and glucocorticoid (methylprednisolone) in both groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the randomized clinical trials of GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction for rheumatoid arthritis: GSZD+MTX versus MTX.

| Study | Number of patientsa | Female % | Age (years, mean ± SD or range) | RA duration (years) | MTX (mg/week) | GSZD (dose/day) | Other drugs | Study duration (weeks) | Effective rateb | Efficacy | Clinical manifestations, laboratory test indicators | AEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou et al.23 | A: 36 B: 33 |

A: 63.89 B: 66.67 |

A: 21–66 B: 23–64 |

A: 2.46 B: 2.52 |

7.5 | +1 | None | 6 | A: 88.89% B: 63.64% |

30% efficacy, 60% efficacy, 90% efficacy | No | No |

| Yuan24 | A: 44 B: 44 |

A: 40.91 B: 36.36 |

A: 20–68 B: 20–70 |

NR | 7.5 | +1 | None | 8 | A: 95.45% B: 75.00% |

ΔDAS28 > 0.6, ΔDAS28 > 1.2 | No | Yes |

| Zhang et al.25 | A: 45 B: 45 |

A: 51.11 B: 53.33 |

A: 37–79 B: 38–78 |

A: 6.11 B: 5.96 |

10 | +1 | None | 11 | A: 91.11% B: 73.33% |

35% efficacy, 75% efficacy | CRP, ESR, RF, DMS | No |

| Xi and Zhang26 | A: 80 B: 75 |

A: 37.5 B: 44.00 |

A: 44–85 B: 45–85 |

A: 12.4 B: 12.2 |

15 | +1 | None | 24 | A: 96.25% B: 84.00% |

60% efficacy, 90% efficacy | DMS, SJC, TJC | Yes |

| Xiao27 | A: 18 B: 18 |

A: 55.56 B: 61.11 |

A: 41 ± 5.1 B: 42 ± 4.6 |

A: 4.5 B: 4.6 |

7.5 | +1 | Dic | 12 | A: 94.44% B: 66.67% |

ACR20, ACR30 | ESR | No |

| Ji28 | A: 83 B: 83 |

A: 44.58 B: 38.55 |

A: 37–66 B: 36–68 |

A: 3.8 B: 3.6 |

7.5 | +1 | IBU | 8 | A: 96.38% B: 80.72% |

ACR20, ACR50 | CRP, ESR, RF | No |

| Cui29 | A: 53 B: 53 |

A: 60.38 B: 64.15 |

A: 36–78 B: 35–78 |

A: 3.61 B: 3.61 |

10 | +1 | IBU | 8 | A: 94.34% B: 81.13% |

35% efficacy, 85% efficacy | CRP, ESR, RF | No |

| Li et al.30 | A: 40 B: 39 |

A: 78.05 B: 73.17 |

A: 45–70 B: 43–69 |

A: 6.64 B: 6.18 |

7.5 | +1 | CLX | 12 | A: 95.00% B: 61.54% |

30% efficacy, 70% efficacy | CRP, ESR, RF | No |

| Yu and Zhang31 | A: 40 B: 41 |

A: 67.50 B: 60.98 |

A: 18–65 B: 20–69 |

A: 6.8 B: 5.4 |

10 | +1 | SSZ | 12 | A: 90.00% B: 70.73% |

ACR20, ACR50, ACR90, | CRP, ESR, DMS, SJC, TJC | Yes |

| Li et al.32 | A: 45 B: 45 |

A: 48.89 B: 46.67 |

A: 21–75 B: 21–76 |

NR | 7.5 | +1 | SSZ | 24 | A: 95.56% B: 77.78% |

ΔDAS28 > 0.6, ΔDAS28 > 1.2 | CRP, ESR, DMS | Yes |

| Huang et al.33 | A: 36 B: 27 |

A: 77.78 B: 85.19 |

A: 21–65 B: 22–64 |

A: 2.75 B: 2.65 |

10 | +1 | SSZ, CLX | 12 | A: 91.67% B: 66.67% |

ACR20, ACR50, ACR80 | CRP, ESR, RF, DMS, SJC, | Yes |

| Liang and Yang34 | A: 40 B: 38 |

A: 55.00 B: 57.89 |

A: 39–79 B: 40–80 |

A: 2.3 B: 2.1 |

10 | +1 | LEF, Dic | 8 | A: 95.00% B: 78.95% |

30% efficacy, 70% efficacy, 95% efficacy | CRP, ESR, RF, DMS, SJC | Yes |

| Dong35 | A: 30 B: 30 |

A: 43.33 B: 46.67 |

A: 52–79 B: 35–78 |

A: 6.10 B: 5.93 |

10 | +1 | SSZ, CLX | 12 | A: 96.67% B: 80.00% |

35% efficacy, 95% efficacy | CRP, ESR, RF, DMS, SJC, | Yes |

| Wu36 | A: 33 B: 30 |

A: 63.64 B: 66.67 |

A: 28–64 B: 31–67 |

A: 5.7 B: 5.5 |

10 | +1 | LEF, MePr | 24 | A: 100% B: 83.33% |

ACR20, ACR50, ACR70, | CRP, ESR, RF, DMS, SJC, TJC, | No |

A = GSZD group; B = control group.

Effective rate is defined as ACR20, 30% or 35% efficacy, ΔDAS28 >0.6.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; AE, adverse event; CLX, celecoxib; CRP, C-reactive protein; ΔDAS28, a decrease of DAS28; DAS28, disease activity score 28; Dic, diclofenac sodium; DMS, duration of morning stiffness; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GSZD, GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction; IBU, ibuprofen; LEF, leflunomide; MePr, methylprednisolone; MTX, methotrexate; NR, not reported; RF, rheumatoid factor; SJC, swollen joint count; SSZ, sulfasalazine; TJC, tender joint count.

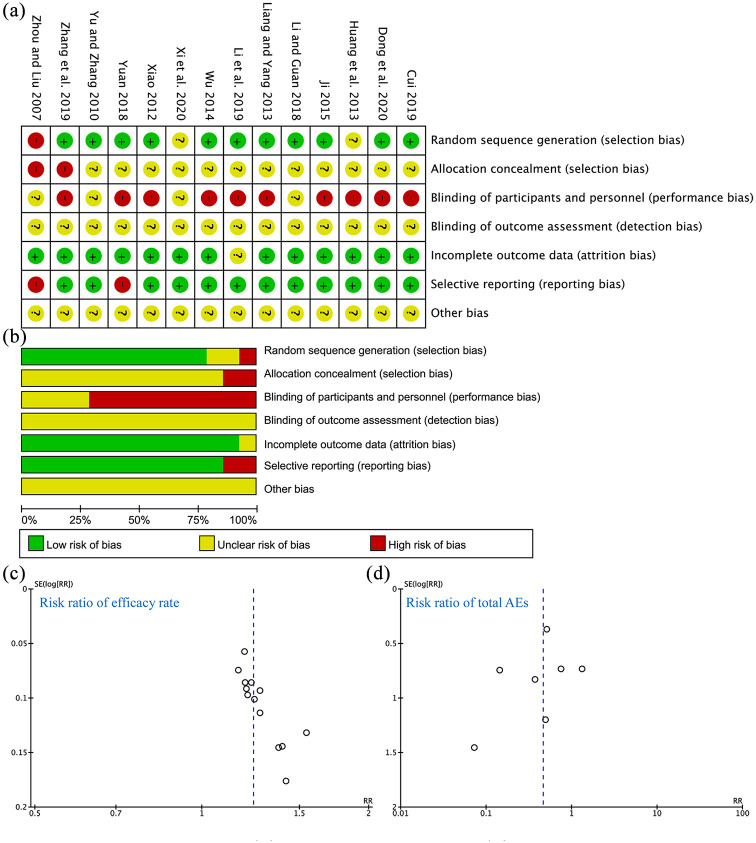

The risk of bias assessment for the included studies is shown in Figure 2. A random sequence was adequately generated in 11 RCTs (78.6%), and the risk of selection bias was judged to be low. The risk of bias for allocation concealment was unclear because most of the studies did not report clear information about the methods used to conceal the allocation. Performance biases were judged to be high or unclear because blinding of participants and personnel was not performed in any RCTs due to the obvious difference between the GSZD and MTX. Moreover, blinding of outcome assessor was unclear in each RCT. The incomplete outcome data element had a low risk of bias for 13 RCTs (92.9%). There was also a low risk of selective outcome reporting for 12 RCTs (85.7%). Other sources of bias were unclear.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias of included RCTs. (a) Summary of risk of bias. (b) Risk of bias graph for each item presented as a percentage across all included studies. (c) Funnel plot for the risk ratio of efficacy rate. (d) Funnel plot for the risk ratio of total AEs.

AE, adverse event; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CI, confidence interval; DAS28, Disease activity score 28; GSZD, GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction; MTX, methotrexate; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Also, the funnel plots for risk ratio of efficacy rate is asymmetric, which indicates that some publication bias for the RCTs, reporting biases or other interference factors may exist, such as poor methodological quality.37

Efficacy

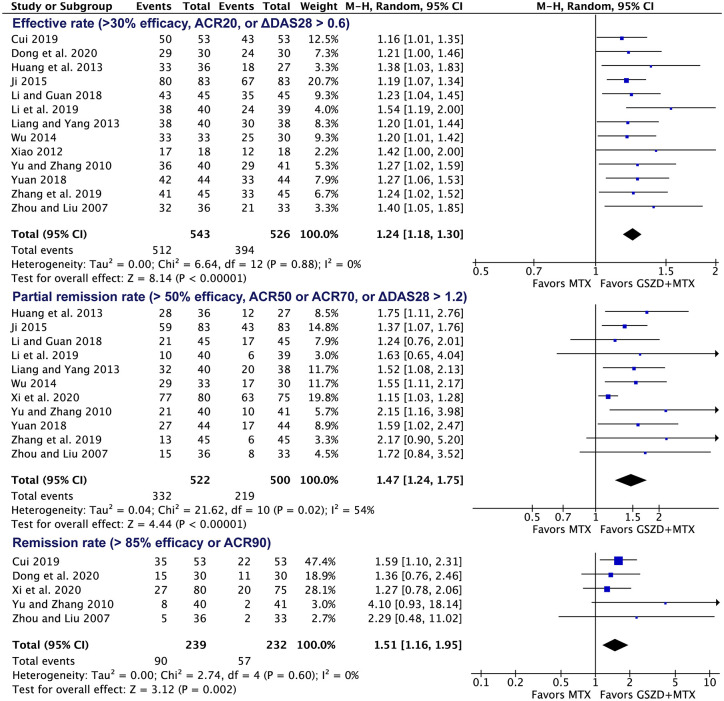

Among the included trials,23–36 (1) 13 RCTs (total of 1069 patients) reported the effective rate,23–25,27–36 defined as >30% efficacy, ACR20, or ΔDAS28 >0.6; (2) 11 RCTs (total of 1022 patients) reported partial remission rate,23–26,28,30–34,36 defined as >50% efficacy, ACR50 or ACR70, or ΔDAS28 >1.2; (3) five RCTs (total of 471 patients) reported the remission rate,23,26,29,31,35 defined as >85% efficacy or ACR90. The meta-analysis indicated that adding GSZD was associated with a higher effective rate (RR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.18–1.30; Figure 3), partial remission rate (RR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.24–1.75; Figure 3) and remission rate (RR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.16–1.95; Figure 3). Of note, the results are similar when excluding each one of these included studies (Supplemental Table 6). The heterogeneity for the effective rate and remission rate is low (I2 <50%), while it is high for partial remission rate (I2 = 54%).

Figure 3.

Forest plot indicating the increased response rates following MTX plus GSZD treatment of RA.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CI, confidence interval; DAS28, Disease activity score 28; GSZD, GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction; MTX, methotrexate; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

In addition, subgroup meta-analysis based on the dose of MTX showed that MTX 7.5 mg/week plus GSZD had a similar effect as MTX 10 mg/week plus GSZD (Supplemental Figure 1). Subgroup meta-analysis according to the additional drugs concurrently used in both groups, including no other drugs, NSAIDs, other DMARDs, and glucocorticoid, showed that the effective rate of the MTX plus GSZD group was still higher than that of the MTX group in all of these conditions (Supplemental Figure 2).

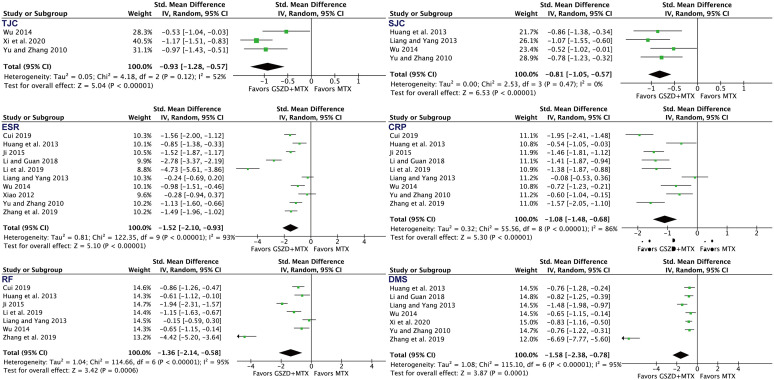

After analyzing symptoms of RA, as shown in Figure 4, we also found that adding GSZD was associated with a higher rate of TJC (standardized mean difference = –0.93, 95% CI: –1.28 to ‒0.57), SJC (standardized mean difference = –0.81, 95% CI: –1.05 to ‒0.57), DMS (standardized mean difference = –1.58, 95% CI: –2.38 to ‒0.78), ESR (standardized mean difference = –1.52, 95% CI: –2.10 to ‒0.93), CRP (standardized mean difference = –1.08, 95% CI: –1.48 to ‒0.68), and RF (standardized mean difference = –1.36, 95% CI: –2.14 to ‒0.58).

Figure 4.

Forest plot indicating the enhanced efficacy on clinical symptoms and laboratory indexes following MTX plus GSZD treatment of RA.

CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; DMS, duration of morning stiffness; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GSZD, GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction; IV, inverse variance; MTX, methotrexate; RF, rheumatoid factor; SJC, swollen joint count; Std., standardized; TJC, tender joint count.

Safety

Seven trials reported AEs.21,24,26,31–34 Out of the 615 patients, 68 experienced at least one AE, 20 out of 315 patients in the experimental group and 48 out of 300 in the control group. As shown in Figure 5, adding GSZD was associated with a lower rate of total AEs (RR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.26–0.83). No withdrawal events due to AEs were found in either group. All AEs occurring in the seven trials are listed in Supplemental Table 7.

Figure 5.

Forest plot indicating decreased rate of total adverse events (AEs) following MTX plus GSZD treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. GSZD add-on group had fewer AEs than the MTX group. Events means AEs.

CI, confidence interval; GSZD, GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel; MTX, methotrexate.

As shown in Figure 6, adding GSZD was associated with a lower rate of gastrointestinal tract AEs (RR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.24–0.88), but it had no significant effect on the rate of liver AEs (RR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.05–1.90), AEs of the nervous system (RR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.24–3.85), or other AEs (RR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.15–2.83). The most common AEs in the MTX plus GSZD group were vertigo (2.3%) and nausea (1.3%), which is comparable to the MTX group (nausea: RR = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.18–0.95) and (vertigo: RR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.22–3.97). Of note, the results for the rate of gastrointestinal tract AEs may also become comparable between two groups when excluding the study of Xi and Zhang26 or Yu and Zhang31 (Supplemental Table 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot for the rate of specific adverse events (AEs) following MTX plus GSZD treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. GSZD add-on group was comparable to or had fewer AEs than MTX group. Events means AEs.

CI, confidence interval; GSZD, GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction; M–H: Mantel–Haenszel; MTX, methotrexate.

Discussion

Methotrexate (MTX) is a first-line synthetic DMARD used in the pharmacological management of RA.38 Due to limited efficacy and intolerance of MTX in many patients, MTX plus GSZD has become a first-line integrated Chinese and western medical therapy strategy for RA in China in recent decades, which may enhance the response rates and reduce the rate of AEs. Using a meta-analysis strategy, we found the following: (1) for efficacy, the combination of GSZD and MTX had a higher effective rate compared with MTX alone (or in a condition of combined utilization of other drugs in both groups); (2) adding GSZD was also associated with lower levels of SJC, TJC, DMS, and ERS, as well as the levels of CRP and RF; and (3) for safety, adding GSZD was associated with a lower rate of the total AEs and the rate of gastrointestinal AEs. Therefore, taken together, our analysis indicated that MTX plus GSZD may be more efficacious and safer than MTX alone for the treatment of RA. Thus, our analysis suggests that MTX combined with GSZD may be a promising therapeutic strategy for the treatment of RA.

A previous meta-analysis showed that GSZD may have equal or superior effectiveness and safety for treating RA compared with western RA drugs, where studies using different western RA drugs were generally pooled together and only two included studies focused on the combination of GSZD and MTX.12 Here we did a more specific meta-analysis on the efficacy and safety of adding GSZD to MTX. Moreover, we collected and included more RCTs, including seven new RCTs that were reported after 2018.24–26,29,30,32,35 Thus, our study provided an update and potentially more reliable evidence supporting the use of MTX plus GSZD for the treatment of RA. Based on 14 RCTs and a total of 1224 patients, our meta-analysis found that adding GSZD was associated with higher response rates, lower rates of SJC, TJC, DMS, and ERS, and lower levels of CRP and RF. The adjuvant therapeutic effect of GSZD was independent of the dose of MTX or the combined utilization of other drugs (such as NSAIDs in both groups). Thus, our results suggested that the combination of GSZD and MTX may be more efficacious than MTX alone for RA patients. Further studies are still warranted to confirm the effect of the combination of GSZD and MTX for RA treatment.

Common AEs were observed in patients treated with MTX involving toxicities in several organs.39 According to a recent systematic review on the side effects of MTX therapy for RA, gastrointestinal AEs were the most frequent AEs associated with MTX.40 In particular, about 11% of RA patients discontinued MTX therapy mainly because of gastrointestinal AEs.41 Our analysis found that adding GSZD was associated with a lower rate of total AEs and the rate of gastrointestinal AEs but did not significantly affect the rate of other AEs. The most common AEs in both MTX plus GSZD and MTX groups were nausea (2.3% for MTX plus GSZD versus 5.6% for MTX) and vertigo (1.3% for MTX plus GSZD versus 2.0% for MTX). Recently, a retrospective cohort study also indicated that adding GSZD was associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke among patients with RA.42 Thus, these results suggest that the combination of GSZD and MTX may be safer than MTX alone for RA patients, especially for patients with MTX related gastrointestinal AEs. Further studies are needed to confirm whether adding GSZD was associated with a lower rate of total AEs.

Similar to most TCM formulas, the mechanism of GSZD is complex and unclear. According to previous network pharmacology studies,10,17 GSZD may target hundreds of RA related proteins and may partially reverse the inflammation–immune system imbalance, which therefore is likely to satisfy the therapeutic outcomes for RA. In a recent animal study, GSZD inhibited many serum proinflammatory cytokine levels, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17a, in collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) rats.43 Though the therapeutic effect of MTX on RA remains unclear, it is well-known that MTX mainly works by inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase,44 which does not seem to be the potential target of GSZD. Thus, these results suggest that the combination of GSZD and MTX may have a complementary effect for RA therapy.

Several limitations in our meta-analysis should be noted as follows: (1) the quality of some trials was poor, such as having an unclear bias for allocation concealment, unclear blinding of outcome assessor, and high risk of performance biases; (2) all included trials were conducted in the Chinese population, which implies a high risk of selection bias; (3) according to the funnel plot, publication bias may exist; (4) although all studies used the basic GSZD formulation, the use of other herbs or drugs may have influenced our analysis. Thus, the clinical interpretation of these findings is limited by these high or unclear risks of bias. Further large and multi-center clinical studies are still warranted.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis preliminarily indicated that the combination of GSZD and MTX is a more effective and safer strategy compared with MTX alone for RA treatment. Of note, as the specific risk of bias and heterogeneity exist, further large and multi-center clinical studies are still needed to investigate the long-term efficacy and safety of the combination of GSZD and MTX for RA treatment.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-taj-10.1177_2040622321993438 for Chinese traditional medicine (GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction) as an add-on medication to methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials by Chenxi Feng, Rongrong Chen, Keer Wang, Chengping Wen and Zhenghao Xu in Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-taj-10.1177_2040622321993438 for Chinese traditional medicine (GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction) as an add-on medication to methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials by Chenxi Feng, Rongrong Chen, Keer Wang, Chengping Wen and Zhenghao Xu in Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Lu Li for her kindness and support during our manuscript revision.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Z.X. designed the study. C.F and R.C. performed the systematic search. C.F and R.C. reviewed studies to extract potentially eligible studies and the data. K.W. helped to check the extracted data for analysis. C.F., K.W., and Z.X. analyzed the data. C.F. and Z.X. wrote the manuscript in consultation with C.W.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Consent statement and ethical approval: Consent statement and ethical approval are not required as the current study was based on published data.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2018YFC1705501) and the Project of the national education steering committee for postgraduate students majoring in traditional Chinese medicine (20190723-FJ-B23), and partly supported by the Program of Zhejiang TCM Science and Technology Plan (2018ZZ007) and Foundation of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (grant numbers ZYX2018002 and Q2019Y02).

ORCID iD: Zhenghao Xu  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0033-525X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0033-525X

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Chenxi Feng, The Second Clinical Medical College, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China.

Rongrong Chen, School of Basic Medical Science, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China.

Keer Wang, School of Basic Medical Science, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China.

Chengping Wen, School of Basic Medical Science, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China.

Zhenghao Xu, School of Basic Medical Science, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Binwen Road 548, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, 310053, China.

References

- 1. McInnes IB, Schett G. Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2017; 389: 2328–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guo Q, Wang Y, Xu D, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis: pathological mechanisms and modern pharmacologic therapies. Bone Res 2018; 6: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roubille C, Richer V, Starnino T, et al. The effects of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors, methotrexate, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids on cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Durán J, Bockorny M, Dalal D, et al. Methotrexate dosage as a source of bias in biological trials in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 1595–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bedoui Y, Guillot X, Sélambarom J, et al. Methotrexate an old drug with new tricks. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. García-Rayado G, Navarro M, Lanas A. NSAID induced gastrointestinal damage and designing GI-sparing NSAIDs. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2018; 11: 1031–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schjerning AM, McGettigan P, Gislason G. Cardiovascular effects and safety of (non-aspirin) NSAIDs. Nat Rev Cardiol. Epub ahead of print 22 April 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s41569-020-0366-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stouten V, Westhovens R, Pazmino S, et al. Effectiveness of different combinations of DMARDs and glucocorticoid bridging in early rheumatoid arthritis: two-year results of CareRA. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019; 58: 2284–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drosos AA, Pelechas E, Kaltsonoudis E, et al. Therapeutic options and cost-effectiveness for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2020; 22: 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang L, Lv Q, Xie D, et al. Deciphering the potential pharmaceutical mechanism of Chinese traditional medicine (Gui-Zhi-Shao-Yao-Zhi-Mu) on rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 22602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guo Q, Mao X, Zhang Y, et al. Guizhi-Shaoyao-Zhimu decoction attenuates rheumatoid arthritis partially by reversing inflammation-immune system imbalance. J Transl Med 2016; 14: 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daily JW, Zhang T, Cao S, et al. Efficacy and safety of GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction for treating rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Altern Complement Med 2017; 23: 756–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zheng X. Guiding principles for clinical study of new Chinese medicines. Beijing, China: China Medical Science Press, 2002, p.392. [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Criteria of diagnosis and therapeutic effect of diseases and syndromes in traditional Chinese medicine. Nanjing, China: Nanjing University Press, 1994, p.219. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shen P. Clinical diagnosis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in traditional Chinese medicine. Beijing, China: People’s Military Medical Press, 2015, p.206. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Tanaka S, et al. Efficacy and safety of peficitinib (ASP015K) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to conventional DMARDs: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial (RAJ3). Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78: 1320–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang G. Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction in the treatment of 30 cases of menopausal rheumatoid arthritis. Guangming J Chin Med 2013; 28: 1853–1854. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang P, Wang F. Clinical observation of 28 cases of rheumatoid arthritis treated with Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction. Chin Modern Doctor 2011; 49: 43-47. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cui G, Pang W. Clinical study of Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Clin Med 2007: 695–696. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu Z, Shi L. Analysis of the regulatory effects of modified Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction on ESR, CRP and RF in active rheumatoid arthritis patients with cold-heat miscellaneous type. Shanxi J Tradit Chin Med 2019; 40: 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Z, Shi L, Zhang T. Clinical study of modified Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction in treating rheumatoid arthritis with cold-heat miscellaneous type. Shanxi J Tradit Chin Med 2019; 40: 906–908–912. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhou A, Liu Y, Li L. Clinical observation on 36 cases of rheumatoid arthritis treated by Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction. Henan Tradit Chin Med 2007; 8: 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yuan N. Effect of Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction on rheumatoid arthritis. Cardiovasc Dis J Integr Trad Chin West Med 2018; 6: 163–164. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang S, Wang L, Liu D, et al. Clinical study on 45 cases of rheumatoid arthritis treated with Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction and methotrexate. Jiangsu J Trad Chin Med 2019; 51: 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xi N, Zhang J. Effect of Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction combined with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Lab Med Clin 2020; 17: 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xiao S. Clinical observation of Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction in treatment of 36 cases with active rheumatoid arthritis. China Modern Med 2012; 19: 112–113+115. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ji X. Clinical observation of rheumatoid arthritis treated by integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine. J Sichuan Trad Chin Med 2015; 33: 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cui C. Clinical observation of modified Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction combined with western medicine in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Chin J Ethnomed Ethnopharm 2019; 28: 128–129. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li J, Lin Y, Yu G, et al. Clinical observation on treating 41 cases of rheumatoid arthritis of mixed heat and cold type with Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu tang combined with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2019; 8: 31–34+42. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu J, Zhang H. Traditional Chinese and Western medicine treatment of refractory rheumatoid arthritis clinical observation. Chin J Exp Trad Medical Formulae 2010; 16: 201–203. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Z, Guan S, Wu W, et al. Curative effect analysis of Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction combined with western medicine on rheumatoid arthritis. Asia-Pacific Trad Med 2018; 14: 191–192. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang J, Cai L, Hu B. Clinical Observation of Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J New Chin Med 2013; 45: 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liang Q, Yang T. Observation of curative effect of integrated traditional Chinese and Western Medicine on rheumatoid arthritis. J Sichuan Trad Chin Med 2013; 31: 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dong J. Clinical effect and safety of modified Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with cold-heat complicated syndrome. Clin Res Pract 2020; 5: 124–125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wu C. Clinical observation of rheumatoid arthritis treated by integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine. J Pract Trad Chin Med 2014; 30: 1115–1117. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Taylor PC, Balsa Criado A, Mongey A-B, et al. How to get the most from Methotrexate (MTX) treatment for your rheumatoid arthritis patient?-MTX in the treat-to-target strategy. J Clin Med 2019; 8: 515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Romao VC, Lima A, Bernardes M, et al. Three decades of low-dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: can we predict toxicity? Immunol Res 2014; 60: 289–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang W, Zhou H, Liu L. Side effects of methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Eur J Med Chem 2018; 158: 502–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Calasan MB, van den Bosch OF, Creemers MC, et al. Prevalence of methotrexate intolerance in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2013; 15: R217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shen HS, Chiang JH, Hsiung NH. Adjunctive Chinese herbal products therapy reduces the risk of ischemic stroke among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol 2020; 11: 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang Q, Peng W, Wei S, et al. Guizhi-Shaoyao-Zhimu decoction possesses anti-arthritic effects on type II collagen-induced arthritis in rats via suppression of inflammatory reactions, inhibition of invasion & migration and induction of apoptosis in synovial fibroblasts. Biomed Pharmacother 2019; 118: 109367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rana RM, Rampogu S, Abid NB, et al. In silico study identified methotrexate analog as potential inhibitor of drug resistant human dihydrofolate reductase for cancer therapeutics. Molecules 2020; 25: 3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-taj-10.1177_2040622321993438 for Chinese traditional medicine (GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction) as an add-on medication to methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials by Chenxi Feng, Rongrong Chen, Keer Wang, Chengping Wen and Zhenghao Xu in Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-taj-10.1177_2040622321993438 for Chinese traditional medicine (GuiZhi-ShaoYao-ZhiMu decoction) as an add-on medication to methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials by Chenxi Feng, Rongrong Chen, Keer Wang, Chengping Wen and Zhenghao Xu in Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease