Abstract

Since the first discovery of its ibuprofen-like anti-inflammatory activity in 2005, the olive phenolic (−)-oleocanthal gained great scientific interest and popularity due to its reported health benefits. (−)-Oleocanthal is a monophenolic secoiridoid exclusively occurring in extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO). While several groups have investigated oleocanthal pharmacokinetics (PK) and disposition, none was able to detect oleocanthal in biological fluids or identify its PK profile that is essential for translational research studies. Besides, oleocanthal could not be detected following its addition to any fluid containing amino acids or proteins such as plasma or culture media, which could be attributed to its unique structure with two highly reactive aldehyde groups. Here, we demonstrate that oleocanthal spontaneously reacts with amino acids, with high preferential reactivity to glycine compared to other amino acids or proteins, affording two products: an unusual glycine derivative with a tetrahydropyridinium skeleton that is named oleoglycine, and our collective data supported the plausible formation of tyrosol acetate as the second product. Extensive studies were performed to validate and confirm oleocanthal reactivity, which were followed by PK disposition studies in mice, as well as cell culture transport studies to determine the ability of the formed derivatives to cross physiological barriers such as the blood-brain barrier. To the best of our knowledge, we are showing for the first time that (-)-oleocanthal is biochemically transformed to novel products in amino acids/glycine-containing fluids, which were successfully monitored in vitro and in vivo, creating a completely new perspective to understand the well-documented bioactivities of oleocanthal in humans.

Keywords: oleocanthal, pharmacokinetics, biological fluids, glycine derivative, oleoglycine, tyrosol acetate

Extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO) is a principal component of the Mediterranean diet and has long been associated with health benefits.1−10 EVOO contains sterols, carotenoids, triterpenic alcohols, and phenolic compounds.11−13 Many phenolic compounds extracted from EVOO have attracted attention since their discovery.7,13,14 Among these phenolic constituents, oleocanthal (2-(p-hydroxyphenyl) ethyl ester of (3S)-4-formyl-3-(2-oxoethyl) hex-4-enoic acid, (1); Figure 1), a naturally occurring secoiridoid,14 has emerged as a potential treatment for chronic inflammatory diseases, various cancers, and progressive neurodegenerative diseases.3−5,15−25 There is a widespread belief that many of the positive health benefits of olive oil are attributable, at least to some extent, to oleocanthal.22−25

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of oleocanthal (1), oleocanthadiol (2), oleoglycine (3a,b) and tyrosol acetate (4).

Despite the extensively reported beneficial effects of oleocanthal, until now, its pharmacokinetic (PK) characteristics have never been described. A recent study has reported the intestinal absorption of oleocanthal in rats using an in situ perfusion technique, which demonstrated oleocanthal can be extensively metabolized by phase I and II metabolizing enzymes.26 In this study, the authors did not report a thorough characterization of the formed metabolites, nor was the interpretation validated.27 Although analysis of oleocanthal either in olive oil or as a purified compound has been done using liquid chromatography (LC) separation coupled with ultraviolet or mass spectrometry (MS) detection,28−34 and by quantitative 1H NMR,35 there are no studies addressing the detection and quantification of oleocanthal in biological fluids such as culture media, human or animal plasma, or tissues.

Oleocanthal contains highly electrophilic functional groups represented by the two-aldehyde groups at C-1 and C-3. These reactive groups made the detection of oleocanthal in biological fluids nearly impossible. When spiked in cell culture medium, plasma, or tissue homogenates, in a solution containing free amino acids, such as glycine, or proteins, such as bovine serum albumin, oleocanthal rapidly becomes undetectable in these samples. Thus, in this work, we aimed to investigate oleocanthal in biological fluids, detect, and then evaluate its transport across an in vitro cell-based model of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and characterize its pharmacokinetics and disposition in mice plasma and brain.

Results and Discussion

Detection of Oleocanthal in Biological Fluids

The detection of oleocanthal in biological fluids is challenging mainly due to its reactive aldehyde groups especially C-3 (Figure 1). Oleocanthal dialdehydic functionality correlates with its reactivity in biological fluids. Both aldehyde groups are associated with extensive unpredictable reactivity with endogenous amino acids, peptides, and proteins, and therefore, the pharmacokinetics of oleocanthal have always been very challenging for olive phenolics researchers. When dissolved in acetonitrile and analyzed by HPLC on a C-18 reversed-phase column, oleocanthal eluted at ∼7.1 min retention time (Figure S1A); however, when prepared in a mixture of water and acetonitrile, an additional peak at 2.3 min was formed, representing the oleocanthal monohydrate (oleocanthadiol, 2; Figure 1 and Figure S1B), which is consistent with previous reports.29,33 Oleocanthal undergoes a spontaneous interaction with water, forming the more polar monohydrate gem-diol by water addition to the C-3 aldehyde, which was further confirmed and characterized by MS (Figure S1C) and by NMR as described below. However, when spiked in cell culture media, mouse, or human plasma samples, oleocanthal peaks were not detectable. As shown in Figure 2, oleocanthal (25 μg/mL) spiked in complete culture medium could not be detected (retention time at 7.1 min and its monohydrate derivative at 2.3 min; Figure 2B); however, new peaks at 4.3 and 1.9 min were observed (Figure 2B), which greatly increased in peak heights when exposed to warming at 60 °C for 2 h (Figure 2C). These results suggested that oleocanthal rapidly reacts with endogenous molecules existing in these biological fluids, leading to the formation of oleocanthal derivatives, and that the formation of these peaks is accelerated by time and temperature.

Figure 2.

Typical chromatograms obtained from spiked oleocanthal in culture medium and glycine solution. (A) Oleocanthal (OC) free culture medium. (B) Culture medium spiked with oleocanthal 25 μg/mL and kept at RT for 2 h, then analyzed. (C) Culture medium spiked with oleocanthal 25 μg/mL and heated for 2 h at 60 °C. (D) 1 mM glycine solution spiked with 100 μg/mL oleocanthal at RT. (E) 1 mM glycine solution spiked with 100 μg/mL oleocanthal and heated for 2 h at 60 °C. (F) Effect of temperature and time on oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate formation. Peaks of OC, oleocanthadiol (OCdiol), oleoglycine (OG), and tyrosol acetate (TA) are shown.

To further confirm this reaction and the effect of temperature on the formation of oleocanthal derived peaks, we spiked oleocanthal into a buffered glycine solution (1 mM glycine in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2), and compared the effect of temperature on the detectability of oleocanthal at room temperature (RT) and 60 °C. Glycine was initially selected for testing because it represents the simplest amino acid and exists in high concentrations (>300 μM) in biological fluids such as plasma and culture media.36 Additional studies were also performed to evaluate the oleocanthal interaction with other amino acids that were further analyzed by NMR as described in the next section. At RT, right after the addition of oleocanthal (100 μg/mL) to the glycine solution, besides oleocanthal and its monohydrate peaks, two additional peaks similar to those observed in Figure 2C were detected (Figure 2D); and when exposed to heat at 60 °C for 2 h, oleocanthal completely disappeared, while the two new peaks significantly increased in peak heights/areas (Figure 2E). These results suggest that the formation of oleocanthal-derived compounds is accelerated by temperature. The ratio of the newly formed peaks differed among culture medium, plasma, and glycine. For example, in culture medium (Figure 2C), both new peak areas were close, while with glycine the less polar peak at 4.3 min was higher than that at 1.9 min (Figure 2D), which could be due to the difference in glycine concentration between the glycine reaction solution and the culture medium, which may also contain other amino acids and proteins that may react with oleocanthal. Next, and based on these results, time (1–24 h) and temperature (37, 45, 60, and 90 °C)-dependent studies were performed to test the reaction of oleocanthal (100 μg/mL) in mouse plasma and complete culture medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS). These temperatures were selected to evaluate the rate of formation of oleocanthal-derived compounds at body temperature and cell culture incubation temperature (37 °C), and to examine the effect of increased temperature on formation rate and stability of formed compounds. Demonstrated in Figure 2F, the formation of the two newly detected peaks in culture medium was time- and temperature- dependent. For reactions tested at temperatures 37, 45, and 60 °C, the first more polar compound (retention time 1.9 min, named oleoglycine, 3) peaked at 2 h, and continued to plateau up to 24 h at 37 and 45 °C, while at 60 °C, the peak reduced after its maximum at 2 h. The second compound (identified as tyrosol acetate, 4) demonstrated a similar behavior except that at 45 °C, the compound concentration decreased with time. The structures of oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate are shown in Figure 1, and their corresponding UV spectra are shown in Figure S1D. At 90 °C, both formed compounds were observed at much lower levels, suggesting instability at this temperature (Figure 2F). Similar behavior was noted in cell culture medium spiked with 100 μg/mL oleocanthal where the same two peaks were produced in a time- and temperature- dependent manner.

Investigation of Oleocanthal Reaction with Amino Acids Other than Glycine, without and with Competitive Amounts of Glycine

Oleocanthal is able to spontaneously react only with primary amines such as those found in glycine or lysine (or even ammonia, methylamine, or hydroxylamine). Oleocanthal reaction with a sterically hindered α-carbon, as found in most amino acids, is less reactive. Oleocanthal was able to react with lysine or alanine that were used as examples of amino acids, affording products that were not further investigated. Interestingly, when oleocanthal came in contact with excess of a mixture of amino acids (glycine, lysine, alanine, arginine, and proline) at equimolar concentrations, only the derivatives of glycine could be observed, validating the high selectivity of the oleocanthal–glycine reaction (Figure S2).

Collectively, these results suggest that in biological fluids, oleocanthal rapidly reacts with amino acids, mostly glycine, which releases two derived products in a time- and temperature-dependent manner.

Identification of Oleocanthal-Derived Compounds in Biological Fluids

Structure Elucidation of Oleoglycine

The structure of the compounds produced from the reaction between E-S-(−)-oleocanthal and glycine was studied in real-time by 1D and 2D NMR experiments inside the NMR tube without chromatographic isolation. All efforts to isolate pure oleoglycine of the reaction with chromatographic methods were unsuccessful leading to its decomposition. Real-time NMR study was performed in solution using the maximum achieved soluble concentration of oleocanthal in D2O, 2 mg/mL, and a 5-fold molar excess concentration of glycine. This highest possible concentration of oleocanthal was selected for the NMR experiments in order to achieve adequate sensitivity to acquire the 2D experiments in less than an hour due to the instability of the reaction product under these conditions. The reaction was spontaneous and completed in 10 min at 25 °C. Higher molar ratio between oleocanthal and glycine led to rapid decomposition (within 5 min) and the formation of a yellow–orange insoluble precipitate. The decomposition problem did not happen at lower concentration of oleocanthal (e.g., 100 μg/mL), but in that case, the amount of the product formed was not enough to record appropriate 2D data in a short time.

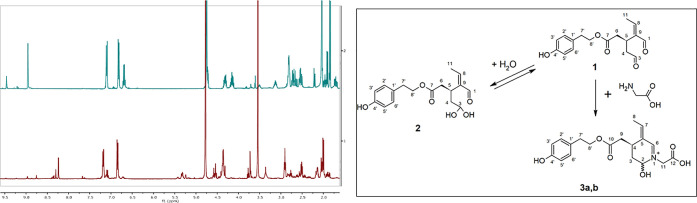

Before the addition of glycine, the 1H NMR spectrum of the solution of oleocanthal showed the presence of a mixture of the dialdehydic form (∼30%) with its hydrated form (oleocanthadiol) (∼70%) in equilibrium. The hydrated form presented a characteristic proton at 4.73 ppm corresponding to the hydrated C-3 aldehyde, the gem-diol (Η-3), while the aldehydic proton of the dialdehydic form (H-3) was observed at 9.48 ppm (Figure 3, green spectrum). The overlapping H-1 aldehyde protons of both compounds, evidenced by integration, were observed at 8.96 ppm. The mixture of the two compounds was studied using COSY, HMQC, and HMBC 2D NMR experiments, and the complete assignment of the 1H and 13C data of both compounds is presented in Table 1. The NMR data of the Ζ-oleocanthadiol in a mixture of D2O and CD3OD was published previously;37 however, our NMR data in pure D2O showed significant chemical shift differences for H-3 (4.72 ppm instead of 4.28 ppm) and for C-3 (89.4 ppm instead of 96.9 ppm). This variation may be attributed to solvent-induced shift (D2O versus D2O–CD3OD mixture) and/or Δ8,9 system geometry inversion. In addition, the 1H NMR data of the dialdehydic form of oleocanthal in D2O are provided herein for the first time showing its optimal solubility in water (Table 1).

Figure 3.

1H NMR spectra of oleocanthal (1) and oleocanthadiol (2) equilibrium in D2O (green spectrum) and the reaction mixture between oleocanthal and glycine (5× excess) after 10 min in D2O (red spectrum). The reaction between oleocanthal with glycine to afford α/β-oleoglycine (3a,b) is also shown.

Table 1. NMR Spectroscopic Data (400 MHz, D2O) of Oleocanthadiol (2) and Oleocanthal (1)a.

| Oleocanthadiol (2) | Oleocanthal (1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| position | δC, type | δΗ (J in Hz) | δΗ (J in Hz) |

| 1 | 199.2, C | 8.96, d, 1.6) | 8.96, d (1.6) |

| 3 | 89.4, CH | 4.73, dd (7.7, 4.2) | 9.48, t (1.2) |

| 4 | 38.5, CH2 | 1.72, ddd (13.5, 7.7, 5.2) | 2.88, ddd (14.5, 8.6, 1.3) |

| 1.99, ddd (13.5, 9.9, 4.2) | 2.80, overlapped | ||

| 5 | 29.7, CH | 3.13, ddt (10.9, 9.9, 5.3 | 3.52, m |

| 6 | 37.4, CH2 | 2.54, dd (14.7, 5.9) | 2.58, dd (14.8, 5.8) |

| 2.72, dd (14.6, 10.9) | 2.68, dd (14.8, 9.8) | ||

| 7 | 175.7, C | ||

| 8 | 159.1, CH | 6.71, q (7.1) | 6.71, q (7.1) |

| 9 | 142.4, C | ||

| 11 | 14.7, CH3 | 1.86, d (7.2) | 1.93, d (7.2) |

| 1′ | 130.6, C | ||

| 2′ | 130.7, CH | 7.13, d (8.4) | 7.13, d (8.4) |

| 3′ | 115.7, CH | 6.84, d (8.4) | 6.85, d (8.4) |

| 4′ | 154.1, C | ||

| 5′ | 115.7, CH | 6.84, d (8.4) | 6.85, d (8.4) |

| 6′ | 130.7, CH | 7.13, d (8.4) | 7.14, d (8.4) |

| 7′ | 33.3, CH2 | 2.84, t (5.4) | 2.83, t (5.4) |

| 8′ | 65.8, CH2 | 4.34, m, overlapped | 4.36, m, overlapped |

| 4.16, dt (11.1, 5.4) | 4.19, dt (11.1, 5.4) |

13C data were obtained indirectly from the 2D spectra.

The addition of glycine to the aforementioned solution led to the spontaneous disappearance of the dialdehydic form evidenced by the obvious disappearance of the downfield aldehyde singlet peak at 9.48 ppm corresponding to the H-3 aldehyde (Figure 3, red spectrum). The second aldehyde peak (H-1) at 8.96 ppm corresponding to oleocanthadiol disappeared after 5 min. Simultaneously, a new set of proton peaks appeared with the most characteristic: a singlet peak at 8.22 ppm (H-6), a dd at 5.32 ppm (H-2), and two doublets at 4.33 and 4.55 ppm (H-11a,b) (Figure 3, red spectrum). Besides those peaks, a similar second set of smaller peaks included a singlet at 8.29 ppm, a dd at 5.23 ppm, and two doublets at 4.40 and 4.53 ppm were recorded. Based on the examination of the 2D NMR COSY, HMQC, and HMBC spectra (Supporting Information (SI) Figures S3–S5), the two sets of the new peaks were assigned to two isomeric compounds bearing a tetrahydropyridinium skeleton for which we propose the names β- and α-oleoglycine (3a,b), respectively. Figure 4 shows that the key correlations permitting the structure elucidation were mainly the 3J-coupling of H-6 with C-2 (82.9 ppm) and C-11 (59.0 ppm) in the HMBC spectrum, confirming the definite assignment of the tetrahydropyridinium skeleton rather than the formation of a simple glycine–imine condensation at the C-1 aldehyde of oleocanthadiol as initially was expected. The 1H–1H-COSY correlation of the methine H-2 with both methylene H2-3 protons H-3a and H-3b (1.87 and 2.14 ppm), which in turn showed a COSY coupling with the broad proton multiplet H-4 (3.35 ppm), further confirmed the tetrahydropyridinium ring formation. The remaining proton and carbon peaks were more or less similar to those observed in the oleocanthadiol spectra and are presented in Table 2. Among the two epimers produced after the reaction of oleocanthal with glycine (Figure 3), the major one corresponded to β-oleoglycine, in which the proton H-2 appeared as a dd peak with J = 10.3 and 3.7 Hz in a pseudoaxial orientation, as suggested by its large axial–axial vicinal coupling with the pseudoaxial proton H-3a. The minor isomer α-oleoglycine H-2 appeared as a dd with J = 3.4 and 1.8 Hz in a pseudoequatorial orientation. The rest of the peaks showed very close similarity in both epimers.

Figure 4.

Selected 1H 1H-COSY (bold), 1H 13C-HMBC (black arrows), and 1H15N-HMBC (green arrows) correlations for compounds 3a and 3b.

Table 2. NMR Spectroscopic Data (400 MHz, D2O) of α- and β-Oleoglycinea.

| β-Oleoglycine

(3a) |

α-Oleoglycine

(3b) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| position | δC, type | δΗ (J in Hz) | δC, type | δΗ (J in Hz) |

| 2 | 82.9, CH | 5.32, dd (10.3, 3.7) | 84.0, CH | 5.23, dd (3.4, 1.8) |

| 3 | 35.0, CH2 | 1.87, ddd (14.8, 10.3, 4.0) | 35.0, CH2 | 2.02 overlapped |

| 2.14, dt (14.8, 3.4) | ||||

| 4 | 30.1, CH | 3.35, br m | 27.9, CH | 3.35, br m |

| 5 | 135.3, C | 135.8, C | ||

| 6 | 173.9, CH | 8.22, s | 173.8, CH | 8.29, s |

| 7 | 165.5, CH | 7.08, q (7.1) | 167.1, CH | 7.19, q (7.1) |

| 8 | 18.8, CH3 | 1.99, d (7.1) | 19.1, CH3 | 2.02, d (7.1) |

| 9 | 39.8, CH2 | 2.80, dd (overlapped) | 39.8, CH2 | 2.80, dd (overlapped) |

| 2.52, dd (overlapped) | 2.52, dd (overlapped) | |||

| 10 | 176.3, C | 176.3, C | ||

| 11 | 59.0, CH2 | 4.33, d (16.1, overlapped) | 61.4, CH2 | 4.40, d (16.1, overlapped) |

| 4.55, d (16.1) | 4.53, d (16.1) | |||

| 12 | 174.1, C | 174.1, C | ||

| 1′ | 133.4, C | 133.4, C | ||

| 2′ | 133.3, CH | 7.17, d (8.3) | 133.3, CH | 7.17, d (8.3) |

| 3′ | 118.3, CH | 6.83, d (8.3) | 118.3, CH | 6.83, d (8.3) |

| 4′ | 157.0, C | 157.0, C | ||

| 5′ | 118.3, CH | 6.83, d (8.3) | 118.3, CH | 6.83, d (8.3) |

| 6′ | 133.3, CH | 7.17, d (8.3) | 133.3, CH | 7.17, d (8.3) |

| 7′ | 36.1, CH2 | 2.89, t (6.0) | 36.1, CH2 | 2.89, t (6.0) |

| 8′ | 69.1, CH2 | 4.35, m, overlapped | 69.1, CH2 | 4.35, m, overlapped |

13C data were obtained indirectly from the 2D spectra.

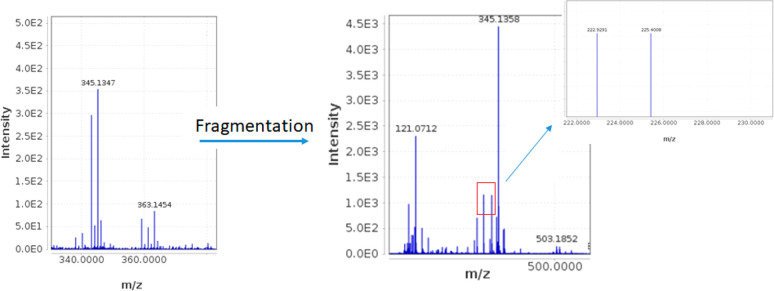

The proposed tetrahydropyridinium structure was further confirmed by HRMS and MS/MS spectra showing a molecular ion at m/z 362 amu. The MS/MS fragmentation pattern and interpretation are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

MS/MS fragmentation spectra provided by LC/Q-TOF analysis of oleoglycine.

Reaction of Oleocanthal with 15N-Enriched Glycine and Oleoglycine Structure Confirmation by Gradient 1H–15N-HMBC

When the oleocanthal–glycine reaction was performed using 15N-enriched glycine, the obtained product showed a molecular weight of 363 amu (Figure 6), with 1 mass unit increase (Figure 6) corresponding to the reaction of one 15N-glycine molecule with one molecule of oleocanthal. The 1H–15N-HBMC spectrum of this compound showed critical correlation 2J-couplings of the methine proton H-2, the olefinic methine proton of the tetrahydropyridinum ring H-6, and the methylene protons H2-11 of the glycine moiety with the 15N-labeled quaternary nitrogen N-1 resonating at 203 ppm. The 1H–15N-HBMC spectrum also showed a 3J-coupling of the two methylene protons H-3a,b with the 15N-labeled quaternary nitrogen N-1, confirming the addition of only one glycine and the formation of the ring (SI Figure S6).

Figure 6.

15N-MS/MS fragmentation spectra provided by LC/Q-TOF analysis of 15N-tagged oleoglycine.

In Situ Investigation of Oleocanthal Reaction with Glycine in D2O by 1H NMR

Ratio and Concentration Effect

At concentrations close to the maximum solubility of oleocanthal in water (2 mg/mL), without buffer, a molar ratio of glycine ×5 is sufficient to achieve a rapid (<10 min) and quantitative (>95%) transformation to oleoglycine; however, in these conditions the formed product is gradually decomposed between 30 and 60 min to derivatives such as 344 and 224 amu (Figure 5), and possibly other compounds. At a higher molar ratio of glycine (e.g., ×10), the decomposition is very fast, <5 min.

At lower oleocanthal concentrations, e.g., 100 μg/mL, a molar ratio ×30 needs 90 min to achieve 50% transformation, but a molar ratio ×300 can achieve the same result in 10 min at 25 °C. This is a very interesting observation since the usual plasma or medium concentration of glycine is ≥300 μM;36 thus, a 1 μΜ concentration of oleocanthal can be easily achieved through either dietary EVOO intake or external pure oleocanthal nutraceutical administration. Additionally, under these conditions, the formed oleoglycine is relatively stable for 30 min to a few hours, depending on the temperature.

Temperature Effect

The reaction was significantly accelerated at 37 °C, compared to reaction at 25 °C. The 1H NMR experiments at both temperatures were performed at oleocanthal concentration of 100 μg/mL and ×300 glycine in D2O (Figure S7). At 37 °C temperature, the reaction was completed in less than 10 min, 3-fold faster than at 25 °C. These results are consistent with those described above in culture medium and mouse plasma (Figure 2F).

Effect of pH

To evaluate the pH effect on the formation of oleocanthal-derived compounds, the oleocanthal–glycine reaction was tested in acidic (pH 2.3) and basic (pH 8.5) conditions. Findings demonstrated that the reaction between oleocanthal and glycine (in concentration 2 mg/mL) was slow in acidic conditions requiring 90 to 180 min to complete (Figure S8), suggesting a slower reaction when compared to neutral pH presented above; on the other hand, increasing the pH to 8.5 using NaHCO3 was detrimental for the reaction products, leading immediately to a complicated mixture of decomposition products including tyrosol (Figure S9). These findings are significant, as they suggest the potential formation of oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate in the stomach acidic pH and upper intestine (close to neutral pH) when orally ingested oleocanthal encounters glycine present in the gastrointestinal tract.

Structure Elucidation of Tyrosol Acetate

Tyrosol acetate (4) was first identified through its mass spectrometry data from oleocanthal spiking in culture medium, showing a molecular ion peak [M + Na]+ at m/z 203 amu, confirming the molecular formula C10H12O3 (Figure 7A and B). The mass and thin layer chromatography patterns were identical to a synthetic standard tyrosol acetate prepared by Mitsunobu esterification reaction of tyrosol with dry glacial acetic acid.19

Figure 7.

Tyrosol acetate (4) spectroscopic confirmation. (A) High-resolution ESI MS/MS fragmentation showing synthetic tyrosol acetate. (B) High-resolution ESI MS/MS from mouse plasma spiked with oleocanthal. (C) 1H NMR spectrum of tyrosol acetate in CDCl3. (D) 1H 13C HMBC spectrum of tyrosol acetate showing the key (red-circled) HMBC correlations.

The 1H NMR spectrum of tyrosol acetate in CDCl3 showed the downfield shift of the oxygenated methylene triplet H2-1 at 4.21 ppm, suggesting its location in the deshielding cone of a nearby ester carbonyl (Figure 7C). The methylene triplet H2-1 in free, nonesterified, tyrosol resonated at 3.81 ppm in CDCl3. The acetate H3-methyl singlet at 2.02 ppm showed a 2J-HMBC coupling with the acetate carbonyl carbon resonating at 172 ppm, confirming the acetate ester. The methylene triplet H2-1 showed 3J-HMBC couplings with the acetate carbonyl at 172 ppm and the aromatic quaternary carbon C-1′ at 130 ppm (Figure 7D). The methylene triplet H2-1 also showed a 2J-HMBC coupling with the methylene carbon C-2 at 34.5 ppm (Figure 7D).

Interestingly, by NMR we were not able to detect tyrosol acetate in the reaction tube; however, it was detected after separation through chromatography (HPLC and MS), suggesting that tyrosol acetate could be a decomposition product of oleoglycine, which is formed during the choromatographic separation process. Indeed, further studies are necessary to confirm this finding. Additional experiments were performed to characterize the formation of tyrosol acetate by reacting oleocanthal with 13C–15N glycine; the obtained product showed the same molecular weight of 203 amu, which indicate that the acetate source in tyrosol acetate is not derived from the glycine.

HPLC Method Validation for Quantitative Analysis of Oleoglycine and Tyrosol Acetate

Next, to validate the HPLC method and quantitatively detect oleocanthal-biological fluid-derived products, calibration curves of oleocanthal in cell culture media (5–200 μg/mL), mouse plasma (1.5–200 μg/mL), and mouse brain homogenates (1.5–50 μg/mL) were constructed and evaluated at 37 °C (cell culture and body temperature) for 2 h. Results from the calibration curves demonstrated a linear relationship between oleocanthal-spiked concentrations and peak areas of formed oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate as determined by the determination coefficient (R2) values that were higher than 0.99 (Table 3A). In addition to R2, the mean (±SD) linear regression equations of the two compounds formed in cell culture media, mouse plasma, and brain homogenates spiked with increasing concentrations of oleocanthal are presented in Table 3A. These findings suggest that the formation of oleocanthal-derived products is dependent on oleocanthal concentration, and these products are valid biomarkers to determine oleocanthal in biological fluids. In addition, the two detected peaks are consistent with those obtained from oleocanthal reaction with glycine, which is logical since glycine exists in high concentration in biological fluids and has the highest reactivity rate with oleocanthal as detailed above.

Table 3. Validation of Oleocanthal-Derived Compounds at 37 °C for 2 h.

| A. Mean (±SD) Linear Regression Equations of the Two Formed Compounds | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| biological matrix | calibration range (μg/mL) | compound | equation | R2 |

| Culture medium | 5–200 | Oleoglycine | y = 672 (±3)x + 278 (±67) | 0.9992 |

| 5–200 | Tyrosol acetate | y = 739.21 (±8)x – 1771 (±200) | 0.9955 | |

| Mouse plasma | 1.25–100 | Oleoglycine | y = 1333 (±62)x – 894 (±13) | 0.9951 |

| 1.25–100 | Tyrosol acetate | y = 1004 (±109)x – 863 (±332) | 0.9942 | |

| Mouse brain | 1.25–50 | Oleoglycine | y = 716 (±15)x – 868 (±119) | 0.9984 |

| Homogenate | 1.25–50 | Tyrosol acetate | y = 3781 (±32)x + 72 (±87) | 0.9948 |

| B. Intra- and Interday Precision Presented as Coefficient of Variation (CV%, n = 5/concentration) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| intraday

precision (CV %) |

interday

precision (CV%) |

|||

| oleocanthal concentration (μg/mL) | oleoglycine | tyrosol acetate | oleoglycine | tyrosol acetate |

| Culture medium | ||||

| 2.5 | 7.0 | 4.4 | 10.4 | 12.7 |

| 5 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 5.2 | 1.4 |

| 100 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 0.3 |

| Mouse plasma | ||||

| 5 | 9.4 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 4.0 |

| 25 | 9.9 | 3.2 | 7.7 | 4.7 |

| 50 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 8.8 | 3.4 |

| C. Freeze and Thaw Stability of Oleocanthal (n = 4/Concentration) Presented as % Difference to Freshly Prepared Samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| culture

medium (%) |

mouse

plasma (%) |

|||

| oleocanthal concentration (μg/mL) | oleoglycine | tyrosol acetate | oleoglycine | tyrosol acetate |

| 2.5 | 84.5 | 87.9 | 113.0 | 103.0 |

| 25 | 107.9 | 94.4 | 97.1 | 90.5 |

| 50 | 98.5 | 104.7 | 111.4 | 97.7 |

To confirm the reproducibility of the produced compounds, the formation of oleocanthal derivatives was validated in cell culture medium and mouse plasma by monitoring intra- and interday precision reaction at 37 °C for 2 h. Intraday precision was assessed by analyzing five replicates of three selected concentrations, prepared by spiking blank samples, on the same day, whereas interday precision reflects the precision when samples were prepared and analyzed on three different days. As demonstrated in Table 3B, intra- and interday precision results of oleocanthal-derived peaks at three representative concentrations prepared in culture medium spiked with oleocanthal to prepare 2.5, 5, and 100 μg/mL were lower than 10.4% for the first compound (oleoglycine), and lower than 12.7% for the second compound (tyrosol acetate). Similarly, intra- and interassay precision results for first and second compounds in mouse plasma (5, 25, 50 μg/mL) were lower than 9.9% and 6.5%, respectively. Collectively, the intra- and interday coefficient of variations of the calibrators was less than 15%, further confirming the assay validity and reproducibility of product formation. We also confirmed the stability of compounds formed in cell culture medium and mouse plasma (Table 3C). Culture medium spiked with 2.5, 25, and 50 μg/mL oleocanthal proved to be stable following two freeze and thaw cycles with accuracy values between 84.5% and 107.9%. In mouse plasma samples, compound stability ranged between 90.5% and 113.0% following two freeze and thaw cycles. These results confirm that for at least two cycles of freeze and thaw of culture medium- and mouse plasma-containing oleocanthal, the formation of oleocanthal-derived products is consistent and reproducible and not affected by the freeze–thaw process.

In Vitro Transport Study across bEnd3 Cells Based BBB Model

To investigate the transport of oleocanthal across the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a transport study across a cellular monolayer grown on filters was performed. Several studies have shown the beneficial effect of oleocanthal against amyloid-related pathology in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models, which suggests that oleocanthal could cross the BBB and thus access the brain.3−5,15,38 To evaluate this assumption, we used the mouse endothelial cells bEnd3 as an in vitro model for the BBB. Cells were seeded on filters for 4 days to form an intact monolayer as we reported previously.39,40 On the fifth day, oleocanthal was added to the upper compartment of the filters at different concentrations (5–200 μg/mL), and its transport across bEnd3 cells monolayer was monitored at different time points by analyzing oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate in the lower compartment. During the transport experiment, cells were kept in the incubator at 37 °C for 1, 2, and 4 h. At the end of each time point, samples were collected from the lower compartment for immediate analysis and after 2 h exposure to 60 °C. Figure 8 shows HPLC chromatograms of oleocanthal-derived peaks in the upper (Figure 8A and B) and lower (Figure 8C–E) compartments obtained from 25 μg/mL oleocanthal addition to the upper side of the filter. Intact oleocanthal could not be detected in either compartment, while both oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate were detected in upper and lower compartments, suggesting their spontaneous formation upon the contact of oleocanthal with the culture medium and both products transported across the in vitro BBB model. In addition to the rapid formation of oleocanthal-derived products at 37 °C, the analysis of collected samples from the upper and lower compartments either immediately or after heating for 2 h at 60 °C following the transport study demonstrated similar levels of oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate, which confirm the formation of both products in the upper compartment and subsequently transported across the monolayer, rather than oleocanthal transport followed by products formation in the lower side of the filter. Figure 8F shows oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate permeability (calculated as apparent permeability in cm/s) across the bEnd3 cells monolayer as a function of concentration of oleocanthal (5–200 μg/mL). The results demonstrated that the permeability of both formed products is concentration-dependent and their transport is a saturable process. In addition, the results suggest the transport of oleocanthal products is carrier(s) mediated. While additional studies are required to identify the transporters, based on oleoglycine structure it could act as a substrate for glycine transporters or organic cation transporters (OCT).

Figure 8.

Typical chromatograms obtained from oleocanthal transport study across bEnd3 cells monolayer. (A) Sample obtained from donor compartment after 1 h of adding culture medium containing 25 μg/mL oleocanthal and directly analyzed. (B) Same sample described for (A) but exposed to heat for 2 h at 60 °C. (C) Sample obtained from receiver compartment after 1 h of adding culture medium containing 25 μg/mL oleocanthal to the donor compartment and directly analyzed. (D) Same sample described for (C) but exposed to heat for 2 h at 60 °C. (E) Sample obtained from receiver compartment after 1 h of adding oleocanthal-free culture medium to the donor compartment and exposed to heat for 2 h at 60 °C. (F) Apparent permeability (Papp, cm/s) of oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate as a function of oleocanthal concentration.

Oleocanthal Disposition in Mouse Plasma and Brain

To investigate the disposition of oleocanthal, mice were intravenously administered with 30 mg/kg oleocanthal through the tail vein. Blood and brain samples were collected up to 8 h following administration; three time points were collected from each mouse, with n = 3 mice for each time point. Plasma was immediately separated from blood samples, and brain tissues were homogenized in PBS (1:1 wt/v). Samples were then analyzed for oleocanthal, oleoglycine, and tyrosol acetate levels by HPLC directly without further exposure to temperature or following incubation for 2 h at 60 °C. To calculate product concentrations, calibration curves obtained from spiked plasma samples with oleocanthal heated for 2 h at 60 °C were used. This condition was used to ensure maximum conversion of oleocanthal to oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate as demonstrated from the temperature- and time-dependent study described earlier. Chromatograms showing products detected in plasma samples obtained from mice administered oleocanthal are shown in Figure 9. As expected, oleocanthal was not detected in any of the plasma samples collected between 5 min and 8 h following its administration. However, oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate were detected in plasma samples without and with heating at 60 °C (Figure 9A and B). In unheated plasma samples, the formation of both products is evident, which is expected due to the mouse body temperature (37 °C) that is appropriate to facilitate the formation of both products (Figure 9A). Compared to unheated plasma samples, however, the levels of oleocanthal-derived products following the exposure to 60 °C were higher (Figure 9A and B).

Figure 9.

Typical chromatograms obtained from mouse plasma and brain homogenate following IV administration of oleocanthal (30 mg/kg, n = 3 mice/time point). (A) Plasma sample after 15 min of oleocanthal dosing and directly analyzed. (B) Same sample described for (A) but exposed to heat for 2 h at 60 °C. (C) Brain homogenate sample obtained before oleocanthal administration exposed to heat for 2 h at 60 °C. (D) Brain homogenate sample after 15 min of oleocanthal dosing and direct analysis. (E) Same sample described for (D) but exposed to heat for 2 h at 60 °C. (F) Mean mouse plasma concentration vs time profiles of oleoglycine (red curves) and tyrosol acetate (black curves) obtained directly without heat and after exposure to heat for 2 h at 60 °C.

The mean plasma concentrations vs time profiles of oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate with and without exposure to heat are shown in Figure 9F, and the calculated pharmacokinetic parameters are listed in Table 4. Compared to directly analyzed samples, exposing plasma samples to heat significantly increased Cmax and AUC of oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate (Table 4). Based on the plasma profiles and parameters shown in Figure 9F and Table 4, respectively, several conclusions could be derived: (1) at mouse body temperature, oleocanthal was not completely converted to the derived compounds, which were enhanced by samples heating at 60 °C especially at early points supporting the formation of intermediate complexes; (2) the calculated half-life values of the products from plasma levels analyzed without further heating do not represent the actual half-life value of oleocanthal, unlike the calculated values at 60 °C, which could better reflect the time oleocanthal circulates in the body (t1/2 = 3.2 and 7.5 h for oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate, respectively); (3) based on calculated half-life values at 60 °C, tyrosol acetate stays in the body for longer time than oleoglycine; and (4) based on the method sensitivity, for plasma samples that were not exposed to heat at 60 °C, we were not able to detect oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate beyond 2 and 4 h, respectively, while heated samples were detected up to 8 h.

Table 4. Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Oleoglycine and Tyrosol Acetate Following a Single Intravenous Administration of 30 mg/kg Oleocanthal to Mice (n = 3 per Three Time Points).

| |

oleoglycine |

tyrosol

acetate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parameter | unit | 37 °C | 60 °C | 37 °C | 60 °C |

| Cmax(@5min) | μg/mL | 29.0 ± 4.4 | 231.6 ± 70.8 | 42.5 ± 4.5 | 191.4 ± 26.6 |

| t1/2 | h | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 7.5 ± 1.6 |

| AUC0-t | mg–h/L | 13.6 ± 1.3 | 93.6 ± 27.1 | 14.9 ± 5.7 | 48.8 ± 4.1 |

| kel | h–1 | 0.366 ± 0.07 | 0.242 ± 0.11 | 0.424 ± 0.15 | 0.095 ± 0.02 |

| CL | L/h | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.34 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 0.62 ± 0.05 |

In addition to plasma disposition, we investigated levels of oleocanthal and its derived products in mouse brains by HPLC following compound extraction. Brain homogenates were analyzed directly and following incubation for 2 h at 60 °C. As shown in Figure 9C–E, oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate were detected in mouse brains. Surprisingly, however, at 60 °C the concentration of oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate were higher than those analyzed directly, which is not consistent with the in vitro findings. While further studies are necessary to explain this finding, it could be related to the high administered dose of oleocanthal, which enabled intact oleocanthal to reach the brain and interact with brain–glycine. Indeed, dose-dependent studies are necessary to evaluate oleocanthal disposition and efficacy, however, in this work, the used high dose of 30 mg/kg in mice was selected only to facilitate the detection and quantitative measurements of the formed peaks using our developed HPLC method that has limited sensitivity.

To calculate oleocanthal permeability into the brain, the partition coefficient (Kp) of oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate from plasma to the brain were determined from the ratio of AUCbrain and AUCplasma of formed oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate after exposure to heat (60 °C for 2 h). Results showed that oleoglycine has a Kp value of 0.27 ± 0.08, and tyrosol acetate has a Kp value of 0.19 ± 0.07. Detecting both products in the brain is significant because it supports reported beneficial effects of oleocanthal to slow the progression of Aβ-related pathology in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models.3−5,15,38 Besides, oleocanthal demonstrated beneficial effects against several other diseases including multiple cancer types.16−20,41 However, and based on our findings, the spontaneous conversion of oleocanthal to oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate suggests that the observed and reported beneficial effects of oleocanthal are mediated by these formed products rather than oleocanthal itself; further studies are indeed necessary to confirm this suggestion, and evaluate which of the formed products, if not both, is responsible for oleocanthal pharmacological effects.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we are reporting for the first time that oleocanthal is biochemically transformed to novel marker products in biological fluids, namely, oleoglycine and tyrosol acetate, which were successfully monitored in vitro and in vivo, creating a completely new perspective to understand the well-documented bioactivities of oleocanthal in humans.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

Oleocanthal was isolated from olive oil as previously described and >99% purity was determined by q1H NMR.41

Time and Temperature-Dependent Studies of Oleocanthal in Biological Fluids

For sample preparation, drug-free cell culture media, mouse plasma, and mouse brain homogenate samples were spiked with oleocanthal to prepare different concentrations in the range of 5–200 μg/mL in cell culture medium, 1.25–50 μg/mL in mouse plasma and brain homogenates. Samples were incubated at different temperatures including RT, 37, 45, 60, and 90 °C for 1, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h. For analysis, 100 μL of each sample was mixed with acetonitrile (1:1 ratio, v/v), vortex mixed for 1 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm. The supernatants were then transferred to HPLC vials and 20 μL from each sample was injected into the HPLC system.

Chromatographic Conditions and Method Validation

All solvents used were HPLC grade and were obtained from VWR Scientific (Suwanee, GA, USA). For sample analysis, an isocratic Prominence Shimadzu HPLC system (Columbia, MD, USA) was used. The system consisted of SIL-20AC Autosampler, SPD-M20A photodiode array detector, and LC-20AB pump connected to a DGU-20A degassing unit. Chromatogram acquisition and processing were carried out using LC Solution software (Shimadzu). The mobile phase used for sample separation consisted of acetonitrile:water (35:65 v/v) delivered at 1.0 mL/min flow rate. The separation was performed at RT on an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm ID; Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The wavelength was set at 230 nm, and the injection volume was 20 μL. While oleocanthal and derived compounds demonstrated maximum absorptivity at 221–224 nm (Figure S1D), we used 230 nm wavelength to avoid any potential interference at lower wavelengths. The UV spectra of oleocanthal and derived compounds were obtained using the photodiode array detector of the HPLC.

For method validation, stock solutions of oleocanthal were prepared in water. A set of six nonzero calibration standards were prepared ranging 5–200 μg/mL in cell culture medium, and 1.25–100 and 1.25–50 μg/mL in mouse plasma and mouse brain homogenates, respectively. To evaluate the linearity of the calibration curves, the analysis of oleocanthal in all matrices was performed on four independent days using fresh preparations. Intraday precision was assessed by analyzing five replicates of three selected concentrations, prepared by spiking blank samples, on the same day, whereas interday precision reflects the precision when samples were prepared and analyzed on three different days. The intra- and interday means, standard deviations, and percentage coefficients of variation (CV) were calculated. The selectivity of the proposed method was assessed by analyzing four blank media, mouse plasma, and mouse brain homogenate samples for possible interferences at the retention time of oleocanthal and its generated products. We also assessed oleocanthal stability by performing freeze–thaw stability study in cell culture medium and mouse plasma. Samples were spiked with oleocanthal at three concentrations 2.5, 25, and 50 μg/mL that were exposed for two cycles of freeze (at −20 °C) and thaw at RT. Spiked samples (n = 4/concentration) were compared with freshly prepared samples at the same concentration levels.

In Vitro Transport Study of Oleocanthal Across a Cell-Based BBB Model

The immortalized mouse brain endothelial cell line, bEnd3 (ATCC; Manassas, VA), were used. bEnd3 cells, passage 25–35, were cultured in DMEM (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (ATCC), penicillin G (100 IU/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) from Cellgro (Thomas Scientific; Swedesboro, NJ). Cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2/95% air) at 37 °C, and media was changed every other day. bEnd3 cells were grown as a monolayer on a 24-well plate (Greiner Bio-One; Monroe, NC) transwell filters to model the BBB following similar protocols to those reported by us previously.39,40 The monolayer was used for transport study on day 5 after preparation. At the day of transport study, 200 μL of oleocanthal solutions at 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL concentrations prepared in media were added to the upper side of the filter. Plates were then incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2/95% air incubator for 1, 2, and 4 h. One hundred microliters were withdrawn from both upper and lower sides of inserts at each time point for analysis. Each sample was analyzed twice, without heating (i.e., under incubator conditions of 5% CO2 and temperature of 37 °C) and with heating at 60 °C for 2 h at the end of transport study. Samples were then extracted with acetonitrile (1:1 ratio, v/v), vortex mixed for 1 min, and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm. The supernatants were transferred to HPLC vials, and 20 μL was injected into the HPLC system. Apparent permeability (Papp) was calculated from the following equation

where dCr/dt is the change in the concentration of oleocanthal (μg/mL) in the receiver compartment as a function of time in seconds, Vr is the volume in the receiver compartment (lower chamber; 1.2 mL), Cd is the concentration of oleocanthal (μg/mL) in the donor compartment at t = 0, and A is the membrane surface area (0.336 cm2).

Pharmacokinetics Study

C57Bl/6J male mice (8–9 weeks old) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed in plastic containers under the conditions of 12 h light/dark cycle, 22 °C, 35% relative humidity, and ad libitum access to water and food. All animal experiments and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Auburn University and according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines, and all surgical and treatment procedures were consistent with the IACUC policies and procedures.

Mice received a single dose of oleocanthal, freshly prepared in sterile saline, administered intravenously through the tail vein at 30 mg/kg dose. Submandibular blood samples were collected at 0 (before administration), 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 2.0, 3.0, 6, and 8 h (n = 3 mice per time point, with maximum of three blood samples collected from each mouse). To collect brain tissues, mice were deeply anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (100/12.5 mg/kg) cocktail, and then were sacrificed at the following time points: 0, 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after injection.

Plasma samples from mice receiving oleocanthal were analyzed twice, without (directly) and with heating for 2 h at 60 °C followed by extraction with acetonitrile (1:1, v/v). For mouse brains, following homogenization in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a 1:1 w/v ratio, samples were analyzed twice, without (directly) and with heating at 60 °C for 2 h followed by extraction with acetonitrile (1:1, v/v) as described for plasma samples.

PK parameters were obtained by noncompartmental method. Peak concentrations (Cmax) were obtained directly from original data, area under the curve for concentrations vs time (AUC0→t) was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule, terminal elimination rate constant (kel) was calculated as the negative slope of the nonweighted least-squares curve fit to logarithmically transformed concentration vs time, elimination half-life (t1/2) and total clearance (CL) were determined by the equations ln 2/kel and dose/AUC, respectively. All data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM).

Confirmatory and Qualitative Analysis by NMR and LC/MS/MS

Reactions

General Procedure

Oleocanthal (2 mg) was slowly dissolved in D2O (1 mL) by staying in contact for 12 h. This solution (or appropriately diluted solutions with D2O) was mixed with a solution of glycine (or other amino acids including lysine, alanine, arginine, or proline) also in D2O. The mixture was transferred in a 5 mm NMR tube and monitored for different periods of time (from 5 min to 24 h) and at two different temperatures (25 and 37 °C). When necessary, pH was adjusted with the addition of PBS, NaHCO3, or H2SO4.

Reaction Monitoring

The monitoring of the reaction progress was performed using NMR spectroscopy with a Bruker Avance DRX 400 MHz. The 1H NMR spectra were processed using either the MNova (Mestrelab Research) or the TOPSPIN software (Bruker, Billerica, MA USA). Typically, 16 scans were collected into 32K data points over a spectral width of 0–12 ppm with a relaxation delay of 1 s. Prior to Fourier transformation (FT), an exponential weighting factor corresponding to a line broadening of 0.3 Hz was applied. 2D experiments, COSY, HMQC, HMBC, and 1H–15N-HMBC were performed using standard Bruker pulse sequences.

β-Oleoglycine (3a): (2R,4S,5E)-1-(carboxymethyl)-5-ethylidene-2-hydroxy-4-{2-[2-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)ethoxy]-2-oxoethyl}-2,3,4,5-tetrahydropyridin-1-ium

α-Oleoglycine (3b): (2S,4S,5E)-1-(carboxymethyl)-5-ethylidene-2-hydroxy-4-{2-[2-(4-hydroxy-phenyl)ethoxy]-2-oxoethyl}-2,3,4,5-tetrahydropyridin-1-ium

1H and 13C NMR data; see Table 2.

For LC/MS/MS, an ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters Corp., USA) was used coupled with a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Q-TOF Premier, Waters) with electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive mode using Masslynx software (v 4.1). 7 μL of each solution was injected onto a C18 column (Eclipse XDB) with a 500 μL/min flow rate of mobile phase solutions A (water) and B (acetonitrile). A gradient system was used beginning at 35% of B solution, held for 11 min, then linear ramp to 98% of B solution in 2 min, and return to 35% of B solution in 1 min with 5 min for re-equilibration. The capillary voltage was set at 3.1 kV, the sample cone voltage was 30 V, and the extraction cone was 4.3 V. The source and desolvation temperatures were maintained at 103 and 300 °C, respectively, with the desolvation gas flow at 700 L/h. The TOF/MS scan was 1.0 s long from 50 to 800 m/z with a 0.1 s interscan delay using the centroid data format. MS/MS scans were 1.0 s long with a 0.02 s interscan delay with a collision energy ramp from 10 to 40 V. The lock mass was used to correct instrument accuracy with a 2 ng/μL solution of Leucine Enkephalin (Bachem part number 4000332).

Preparation of Tyrosol Acetate via a Nucleophilic Substitution-Mitsunobu Esterification Reaction

The Mitsunobu reaction was utilized to synthesize standard tyrosol acetate starting with tyrosol.19 Tyrosol, (Tyr) 138 mg, 1 mmol, was dissolved in dry glacial acetic acid (60 mg, 1 mmol). The mixture was mixed with a precooled anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF, 3.5 mL). Triphenylphosphine (TPP, 280 mg, 1 mmol) was then gradually added in portions, and the resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min in an ice bath at 0 °C. During that time, diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD, 208 μL, 1 mmol) was added dropwise to the mixture. The reaction mixture was warmed and kept stirring at RT for 4 h. The reaction was monitored until complete depletion of tyrosol by thin layer chromatography (TLC, 1:1 n-hexane–EtOAc mixture). Once the reaction was completed, the mixture was worked up by removal of the solvent under reduced pressure. A saturated solution of NaHCO3 (10 mL) was then added to neutralize the excess acid, and the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc, 3 × 20 mL). The organic layers were passed through anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and the filtrate evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was subjected to Sephadex LH- 20 using isocratic CH2Cl2 to afford pure tyrosol acetate (>98% purity), which was established based on q1H NMR analysis (JEOL Eclipse ECS-400 NMR spectrometer, JEOL USA, INC., Peabody, MA, USA).

Acknowledgments

This research work was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS) under grant number R21NS101506 (A.K., M.R., P.P.), the Louisiana Board of Regents, Award Number LEQSF (2017-20-RD-B-07) (K.E.), and World Olive Center for Health (A.R., P.D.). The authors would like to acknowledge Ihab Abdallah for his support in the transport studies and Euitaek Yang for his support in PK studies.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsptsci.0c00166.

HPLC chromatograms for oleocanthal in acetonitrile and water; COSY, HMBC, HSQC-DEPT, and 15N-HMBC spectra of oleoglycine in D2O; 1H NMR spectra of the reaction between oleocanthal and glycine at different temperatures and pHs; 1H NMR spectra of the reaction between oleocanthal and an equimolar mixture of glycine, lysine, and alanine (PDF)

Author Contributions

# L.D, A.R., A.B., M.H., N.T., P.D., and M.B. performed research. M.B., M.R., P.P., E.M., K.E., P.M., and A.K. analyzed and interpreted data, drafted the manuscript with contribution from all authors. P.M. and A.K. supervised the research. L.D. and A.R. contributed equally.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Amal Kaddoumi and Khalid El Sayed are Chief Scientific Officers without compensation in the Shreveport, Louisiana-based Oleolive, LLC. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Franconi F.; Campesi I.; Romani A. (2020) Is extra virgin olive oil an ally for women’s and men’s cardiovascular health?. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2020, 6719301. 10.1155/2020/6719301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongwarawipat T.; Papageorgiou N.; Bertsias D.; Siasos G.; Tousoulis D. (2017) Olive oil-related anti-inflammatory effects on atherosclerosis: potential clinical implications. Endocr., Metab. Immune Disord.: Drug Targets 18, 51–62. 10.2174/1871530317666171116103618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Rihani S. B.; Darakjian L. I.; Kaddoumi A. (2019) Oleocanthal-rich extra-virgin olive oil restores the blood-brain barrier function through NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition simultaneously with autophagy induction in TgSwDI mice. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 10, 3543–3554. 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batarseh Y. S.; Kaddoumi A. (2018) Oleocanthal-rich extra-virgin olive oil enhances donepezil effect by reducing amyloid-β load and related toxicity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 55, 113–123. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qosa H.; Batarseh Y. S.; Mohyeldin M. M.; El Sayed K. A.; Keller J. N.; Kaddoumi A. (2015) Oleocanthal enhances amyloid-β clearance from the brains of TgSwDI mice and in vitro across a human blood-brain barrier model. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 6, 1849–1859. 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginter E.; Simko V. (2015) Recent data on Mediterranean diet, cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and life expectancy. Bratislava Medical Journal. 116, 346–348. 10.4149/BLL_2015_065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque-Sierra A.; Alvarez-Amor L.; Kleemann R.; Martin F.; Varela L. M. (2018) Extra-virgin olive oil with natural phenolic content exerts an anti-inflammatory effect in adipose tissue and attenuates the severity of atherosclerotic lesions in Ldlr–/– Leiden mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 62, 1800295. 10.1002/mnfr.201800295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardener H.; Caunca M. R. (2018) Mediterranean diet in preventing neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 7, 10–20. 10.1007/s13668-018-0222-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitozzi V.; Jacomelli M.; Zaid M.; Luceri C.; Bigagli E.; Lodovici M.; Ghelardini C.; Vivoli E.; Norcini M.; Gianfriddo M.; Esposto S.; Servili M.; Morozzi G.; Baldi E.; Bucherelli C.; Dolara P.; Giovannelli L. (2010) Effects of dietary extra-virgin olive oil on behavior and brain biochemical parameters in ageing rats. Br. J. Nutr. 103, 1674–1683. 10.1017/S0007114509993655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A. (1995) Mediterranean diet and public health: Personal reflections. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 61, 1321S–1323S. 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1321S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripoli E.; Giammanco M.; Tabacchi G.; Di Majo D.; Giammanco S.; La Guardia M. (2005) The phenolic compounds of olive oil: structure, biological activity and beneficial effects on human health. Nutr. Res. Rev. 18, 98–112. 10.1079/NRR200495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García A.; Rodríguez-Juan E.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez G.; Rios J. J.; Fernández-Bolaños J. (2016) Extraction of phenolic compounds from virgin olive oil by deep eutectic solvents (DESs). Food Chem. 197, 554–561. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presti G.; Guarrasi V.; Gulotta E.; Provenzano F.; Provenzano A.; Giuliano S.; Monfreda M.; Mangione M. R.; Passantino R.; San Biagio P. L.; Costa M. A.; Giacomazza D. (2017) Bioactive compounds from extra virgin olive oils: Correlation between phenolic content and oxidative stress cell protection. Biophys. Chem. 230, 109–116. 10.1016/j.bpc.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp G. K.; Keast R. S.; Morel D.; Lin J.; Pika J.; Han Q.; Lee C. H.; Smith A. B.; Breslin P. A. (2005) Phytochemistry: ibuprofen-like activity in extra-virgin olive oil. Nature 437, 45–46. 10.1038/437045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuznait A. H.; Qosa H.; Busnena B. A.; El Sayed K. A.; Kaddoumi A. (2013) Olive-oil-derived oleocanthal enhances β-amyloid clearance as a potential neuroprotective mechanism against Alzheimer’s disease: in vitro and in vivo studies. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 4, 973–982. 10.1021/cn400024q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique A. B.; Ayoub N. M.; Tajmim A.; Meyer S. A.; Hill R. A.; El Sayed K. A. (2019) (−)-Oleocanthal prevents breast Cancer locoregional recurrence after primary tumor surgical excision and neoadjuvant targeted therapy in orthotopic nude mouse models. Cancers 11 (pii), 637. 10.3390/cancers11050637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique A. B.; Kilgore P. C. S. R.; Tajmim A.; Singh S.; Meyer S.; Jois S. D.; Cvek U.; Trutsch M.; El Sayed K. A. (2020) (−)-Oleocanthal as a dual c-MET-COX2 inhibitor for the control of lung cancer. Nutrients 12, 1749. 10.3390/nu12061749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub N. M.; Siddique A. B.; Ebrahim H. Y.; Mohyeldin M. M.; El Sayed K. A. (2017) The olive oil phenolic (−)-oleocanthal modulates estrogen receptor expression in luminal breast cancer in vitro and in vivo and synergizes with tamoxifen treatment. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 810, 100–111. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohyeldin M. M.; Busnena B. A.; Akl M. R.; Dragoi A. M.; Cardelli J. A.; El Sayed K. A. (2016) Novel c-Met inhibitory olive secoiridoid semisynthetic analogs for the control of invasive breast cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 118, 299–315. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elnagar A. Y.; Sylvester P. W.; El Sayed K. A. (2011) (−)-Oleocanthal as a c-Met inhibitor for the control of metastatic breast and prostate cancers. Planta Med. 77, 1013–1019. 10.1055/s-0030-1270724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal K.; Melliou E.; Li X.; Pedersen T. L.; Wang S. C.; Magiatis P.; Newman J. W.; Holt R. R. (2017) Oleocanthal-rich extra virgin olive oil demonstrates acute anti-platelet effects in healthy men in a randomized trial. J. Funct. Foods 36, 84–93. 10.1016/j.jff.2017.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco V.; Ruiz-Fernández C.; Lahera V.; Lago F.; Pino J.; Skaltsounis L.; González-Gay M. A.; Mobasheri A.; Gómez R.; Scotece M.; Gualillo O. (2019) Natural molecules for healthy lifestyles: Oleocanthal from extra virgin olive oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 3845–3853. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigacci S. (2015) Olive oil phenols as promising multi-targeting agents against Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 863, 1–20. 10.1007/978-3-319-18365-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotece M.; Conde J.; Abella V.; Lopez V.; Pino J.; Lago F.; Smith A. B. 3rd; Gómez-Reino J. J.; Gualillo O. (2015) New drugs from ancient natural foods. Oleocanthal, the natural occurring spicy compound of olive oil: a brief history. Drug Discovery Today 20, 406–410. 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas L.; Russell A.; Keast R. (2011) Molecular mechanisms of inflammation. Anti-inflammatory benefits of virgin olive oil and the phenolic compound oleocanthal. Curr. Pharm. Des. 17, 754–768. 10.2174/138161211795428911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Yerena A.; Vallverdú-Queralt A.; Mols R.; Augustijns P.; Lamuela-Raventós R. M.; Escribano-Ferrer E. (2020) Absorption and intestinal metabolic profile of oleocanthal in rats. Pharmaceutics 12, 134. 10.3390/pharmaceutics12020134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaddoumi A.; El Sayed K. A. (2020) Comments on the published article entitled “Absorption and intestinal metabolic profile of oleocanthal in rats. Pharmaceutics 12, 720. 10.3390/pharmaceutics12080720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanakis P.; Termentzi A.; Michel T.; Gikas E.; Halabalaki M.; Skaltsounis A. L. (2013) From olive drupes to olive oil. An HPLC-orbitrap-based qualitative and quantitative exploration of olive key metabolites. Planta Med. 79, 1576–1587. 10.1055/s-0033-1350823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celano R.; Piccinelli A. L.; Pugliese A.; Carabetta S.; Sanzo R. D.; Rastrelli L.; Russo M. (2018) Insights into the analysis of phenolic secoiridoids in extra virgin olive oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 6053–6063. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsolakou A.; Diamantakos P.; Kalaboki I.; Mena-Bravo A.; Priego-Capote F.; Abdallah I. M.; Kaddoumi A.; Melliou E.; Magiatis P. (2018) Oleocanthalic acid, a chemical marker of olive oil aging and exposure to a high storage temperature with potential neuroprotective activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 7337–7346. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R.; Melliou E.; Zweigenbaum J.; Mitchell A. E. (2018) Quantitation of oleuropein and related phenolics in cured Spanish-style green, California-style black ripe, and Greek-style natural fermentation olives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 2121–2128. 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b06025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoni O. S.; Karampetsou K.; Kyriazis I. D.; Stathopoulos P. (2018) Phytomedicine evaluation of total phenolic fraction derived from extra virgin olive oil for its antileishmanial activity. Phytomedicine 47, 143–150. 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Medina V.; Miho H.; Melliou E.; Magiatis P.; Priego-Capote F.; Luque de Castro M. D. (2017) Quantitative method for determination of oleocanthal and oleacein in virgin olive oils by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta 162, 24–31. 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalogiouri N. P.; Aalizadeh R.; Thomaidis N. S. (2018) Application of an advanced and wide scope non-target screening work fl ow with LC-ESI-QTOF-MS and chemometrics for the classification of the Greek olive oil varieties. Food Chem. 256, 53–61. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.02.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkoula E.; Skantzari A.; Melliou E.; Magiatis P. (2012) Direct measurement of oleocanthal and oleacein levels in olive oil by quantitative (1)H NMR. Establishment of a new index for the characterization of extra virgin olive oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 11696–11703. 10.1021/jf3032765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein W. H.; Moore S. (1954) The Free Amino Acids of Human Blood Plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 211, 915–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scognamiglio M.; D’Abrosca B.; Fiumano V.; Golino M.; Esposito A.; Fiorentino A. (2014) Seasonal phytochemical changes in Phillyrea angustifolia L.: Metabolomic analysis and phytotoxicity assessment. Phytochem. Lett. 8, 163–170. 10.1016/j.phytol.2013.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batarseh Y. S.; Mohamed L. A.; Al Rihani S. B.; Mousa Y. M.; Siddique A. B.; El Sayed K. A.; Kaddoumi A. (2017) Oleocanthal ameliorates amyloid-β oligomers’ toxicity on astrocytes and neuronal cells: In vitro studies. Neuroscience 352, 204–215. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qosa H.; Batarseh Y. S.; Mohyeldin M. M.; El Sayed K. A.; Keller J. N.; Kaddoumi A. (2015) Oleocanthal enhances amyloid-β clearance from the brains of TgSwDI mice and in vitro across a human blood-brain barrier model. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 6, 1849–1859. 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qosa H.; Mohamed L. A.; Al Rihani S. B.; Batarseh Y. S.; Duong Q. V.; Keller J. N.; Kaddoumi A. (2016) High-throughput screening for identification of blood-brain barrier integrity enhancers: A drug repurposing opportunity to rectify vascular amyloid toxicity. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 53, 1499–1516. 10.3233/JAD-151179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique A. B.; Ebrahim H.; Mohyeldin M.; Qusa M.; Batarseh Y.; Fayyad A.; Tajmim A.; Nazzal S.; Kaddoumi A.; El Sayed K. (2019) Novel liquid-liquid extraction and self-emulsion methods for simplified isolation of extra-virgin olive oil phenolics with emphasis on (−)-oleocanthal and its oral anti-breast cancer activity. PLoS One 14, e0214798 10.1371/journal.pone.0214798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.