Abstract

Objective:

Glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) promoter methylation influences cellular expression of the glucocorticoid receptor and is a proposed mechanism by which early life stress impacts neuroendocrine function. Mitochondria are sensitive and responsive to neuroendocrine stress signaling through the glucocorticoid receptor, and recent evidence with this sample and others shows that mitochondrial DNA copy number (mtDNAcn) is increased in adults with a history of early stress. No prior work has examined the role of NR3C1 methylation in the association between early life stress and mtDNAcn alterations.

Methods:

Adult participants (n=290) completed diagnostic interviews and questionnaires characterizing early stress and lifetime psychiatric symptoms. Medical conditions, active substance abuse, and prescription medications other than oral contraceptives were exclusionary. Subjects with a history of lifetime bipolar, obsessive-compulsive, or psychotic disorders were excluded; individuals with other forms of major psychopathology were included. Whole blood mtDNAcn was measured using qPCR; NR3C1 methylation was measured via pyrosequencing. Multiple regression and bootstrapping procedures tested NR3C1 methylation as a mediator of effects of early stress on mtDNAcn.

Results:

The positive association between early adversity and mtDNAcn (p=.02) was mediated by negative associations of early adversity with NR3C1 methylation (p=.02) and NR3C1 methylation with mtDNAcn (p<.001). The indirect effect involving early adversity, NR3C1 methylation, and mtDNAcn was significant (95% CI [.002, .030]).

Conclusions:

NR3C1 methylation significantly mediates the association between early stress and mtDNAcn, suggesting that glucocorticoid receptor signaling may be a mechanistic pathway underlying mtDNAcn alterations of interest for future longitudinal work.

Keywords: early life stress, mitochondrial DNA copy number: glucocorticoid receptor methylation, adversity: adverse childhood experiences, trauma

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 61% of adults in the United States experienced some form of early life stress defined as abuse, neglect, parental separation, or poverty (Merrick et al., 2018). Traumatic early life exposures are associated with an increased risk for many poor health outcomes, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and psychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Vachon et al., 2015). These conditions exact costs in excess of $124 billion through suffering, disability, treatment, and loss of productivity over the lifespan (Fang et al., 2012), making early stress exposures an important public health problem. Therefore, toward the goal of disorder prevention or treatment, there is great interest in understanding the molecular pathways impacted after exposure to early life stress.

Early life stress is linked to alterations in the neuroendocrine stress response system and changes to mitochondrial DNA and function (Picard et al., 2014; Ridout et al., 2016) Early life stress in the form of prolonged, repetitive, or severe adversity in the absence of a nurturing environment can result in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation (Danese and McEwen, 2012; Tyrka et al., 2016c). HPA hyper- or hyporeactivity after toxic stress can result in increased risk of stress-related psychiatric disorders (Syed and Nemeroff, 2017; Tyrka et al., 2016c).

Mounting evidence shows that a key mechanism linking early life experiences to changes in neuroendocrine function is epigenetic modification of genes central to the neuroendocrine stress response (Syed and Nemeroff, 2017; Tyrka et al., 2016c). Methylation at CpG nucleotides in gene promoter regions has been of particular interest given their important role in the dynamic regulation of gene expression (Suzuki and Bird, 2008). Epigenetic alterations of neuroendocrine genes have been detected after early life stress exposure (Tyrka et al., 2016c) and are associated with risk for psychiatric disorders (Klengel and Binder, 2015; Syed and Nemeroff, 2017; Tyrka et al., 2016c). Much of this work has focused on promoter methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) gene, NR3C1 (Tyrka et al., 2016c). The GR is responsible for intracellular responses to neuroendocrine signaling, and intracellular GR expression is reduced with promoter methylation of NR3C1 (Daskalakis and Yehuda, 2014; Turner et al., 2010; Tyrka et al., 2016c). This in turn results in reduced GR-mediated glucocorticoid negative feedback and increases in corticosterone responses (Francis et al., 1999; Liu et al., 1997). Most work also shows this positive association between NR3C1 methylation and measures of glucocorticoid activity (Palma-Gudiel et al., 2015; Stonawski et al., 2018; Tyrka, 2016).

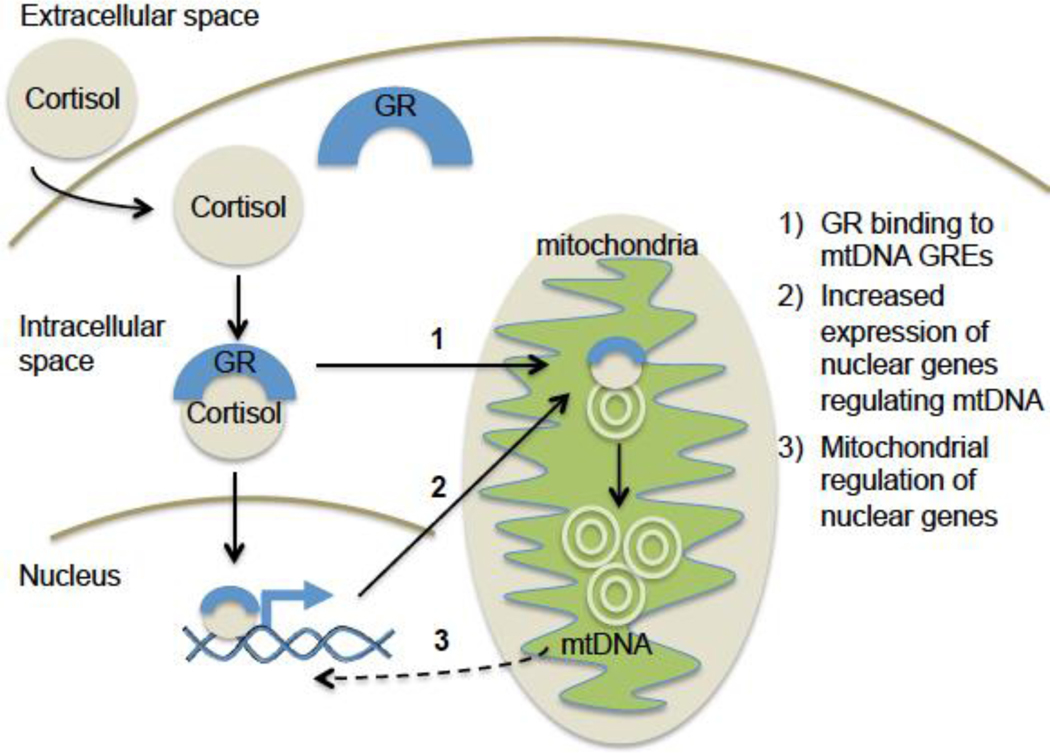

A central target of intracellular glucocorticoid signaling critical to responding and adapting to stress is the mitochondrion (Picard et al., 2014; Ridout et al., 2016). Mitochondria are intracellular organelles that generate ATP, the main energy source in the cell, through the process of oxidative phosphorylation. Mitochondria, which supply the large energy requirements needed to mount the stress response, are particularly vital for highly metabolically active organs such as the brain (Manoli et al., 2007). Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is controlled by a complex cascade of enzymes that is tightly regulated through nuclear and mitochondrial gene expression pathways (Lee et al., 2013; Manoli et al., 2007). In addition to providing the main source of cellular energy, mitochondria are integral to cellular signaling, differentiation, replication, inflammation, and apoptosis (Streck et al., 2014). Glucocorticoid signaling through the GR can modify mitochondrial activity by binding to and regulating mitochondrial and nuclear gene expression (Lee et al., 2013; Psarra and Sekeris, 2009, 2011), in addition to altering cellular processes that regulate mitochondrial genome replication leading to changes in mitochondrial DNA copy number (mtDNAcn) (Lee et al., 2013; Psarra and Sekeris, 2008, 2009) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms by which the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) contributes to mitochondrial DNA copy number (mtDNAcn) regulation.

After intracellular cortisol binds the GR, the activated GR can impact mitochondrial DNA copy number via a variety of mechanisms: 1) GR can enter the mitochondrion, bind to glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) in the mtDNA and directly activate its replication; 2) GR can directly bind to GREs in the nuclear genome and increase transcription of genes that regulate mtDNAcn; and 3) GR-mediated increases in mtDNAcn or modification of intracellular oxidative stress and inflammation pathways can lead to further activation of nuclear genes that enhance mtDNA replication.

Recent evidence suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction may be involved in the development of depressive and anxiety disorders. In rodent models, pharmacological inhibition of mitochondrial function induces anxiety phenotypes (Hollis et al., 2015) and mitochondrial dysfunction is observed in rodent models of MDD (Rezin et al., 2008; Seibenhener et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2016) and PTSD (Garabadu et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). In humans, preliminary evidence shows mitochondrial involvement in PTSD (Bersani et al., 2016; Su et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2015), and MDD (Karabatsiakis et al., 2014; Moreno et al., 2013; Nicod et al., 2015) as well as transdiagnostic behaviors and symptoms, including anergia, psychomotor retardation, memory impairment, and fatigue (Karabatsiakis et al., 2014), as well as somatization (Gardner and Boles, 2008). Alterations in neuroendocrine signaling have been implicated in the link between psychiatric disorders and mitochondrial function (Cai et al., 2015; Liu and Zhou, 2012; Yang et al., 2016). In rodents, chronic stress or corticosterone exposure increases mitochondrial DNA replication (Cai et al., 2015), and repeated injection of corticosterone reduces brain mitochondrial activity while inducing depressive (Liu and Zhou, 2012; Yang et al., 2016) and anxiety phenotypes (Yang et al., 2016). Further, in adult mice with mitochondrial gene deletions, neuroendocrine function after restraint stress is altered and induces depressive phenotypes (Picard et al., 2015). Thus, changes in mitochondrial biogenesis may be an important downstream molecular target of NR3C1 gene expression changes after methylation and may impact risk for the development of psychiatric disorders.

We recently reported that adults with a history of early life stress or psychiatric disorders had increases in mtDNAcn (Tyrka et al., 2015; Tyrka et al., 2016a) and reduced methylation of NR3C1 (Tyrka, 2016). Given the evidence of neuroendocrine dysfunction after early life stress, these findings may be due to an impact on mtDNAcn through a neuroendocrine pathway. Since GR is an important regulator of mitochondria and mtDNAcn, in the present study we hypothesized that NR3C1 methylation may be a mechanism by which early life stress alters mtDNAcn.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Subjects

Adults aged 18–65 (n = 290) were recruited using newspaper and internet advertisements directed toward healthy adults and individuals with psychiatric disorders and/or a history of early life stress. These participants were studied in our prior publication on associations of early stress and psychopathology with mtDNAcn (Tyrka et al., 2016a). Participants self-identified as white (n = 241), black (n = 26), Asian (n = 9), Hispanic (n = 4), and other (n = 10). Subjects free of current substance-use disorders (defined as meeting DSM-IV criteria in the past month) and without current or lifetime bipolar, obsessive-compulsive, or psychotic disorders were included. Medical conditions and prescription medications other than oral contraceptives were exclusionary. Prior to study enrollment, participants were informed about the study and voluntary written informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Butler Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographics.

Age, sex, race, and highest educational level were obtained by subject self-report. Height and weight were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula (weight [kg]/height [m2]).

Early Life Stress Assessment.

Subjects were asked whether they experienced parental loss prior to age 18, defined as parental death and/or parental separation for at least 6 months with no attempts by the parent to contact or respond to the child. Maltreatment was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) 28-item version, which evaluates physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and physical and emotional neglect (Bernstein et al., 2003). Participants were considered to have experienced early life adversity if they endorsed parental loss or had at least moderate levels of one or more of the five maltreatment types on the CTQ.

Psychiatric Disorders.

Psychiatric diagnoses were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First MB, 1997).

DNA Isolation and Measurement of mtDNAcn and NR3C1 Methylation

DNA Isolation.

Whole blood was drawn from participants and then stored at −80° C until processing. DNA was isolated from whole blood using standard techniques.

mtDNAcn Quantification.

Three parallel qPCRs reactions were performed to quantitate copy numbers for the mitochondrial genome and the beta-hemoglobin gene as a single-copy standard as previously described (O’Callaghan, 2011). Data acquisition was performed using the ABI Prism HT79000 DNA Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, New York). qPCR was performed in 384-well plates with a reaction volume of 10 mL containing 25 ng of genomic DNA, 300 nmol/L of each primer, and Sybr Select Master Mix (Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island, New York). Each reaction plate contained wells with serial dilutions of a cloned amplicon (containing a mtDNA and beta-hemoglobin amplicon) to generate standard curves and permit absolute quantitation of mitochondrial DNA and beta-hemoglobin copy number. Mitochondrial forward and reverse primer sequences were directed toward the D-loop region: CAT CTG GTT CCT ACT TCA GGG and TGA GTG GTT AAT AGG GTG ATA GA. Forward and reverse primers for the beta-hemoglobin gene were: GCT TCT GAC ACA ACT GTG TTC ACT AGC and CAC CAA CTTCAT CCA CGT (Bai and Wong, 2005). As previously described (Tyrka et al., 2015; Tyrka et al., 2016a), the initial heating step of 95 °C for 10 minutes was followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 1 minute. PCR efficiency criteria were 99–104% for both measures. Coefficients of variation (CVs) were calculated within each triplicate and samples with CVs > 5% were repeated. MtDNA copy number was divided by the beta-hemoglobin gene copy number to obtain the final value of mtDNAcn per cell.

NR3C1 Promoter Methylation.

In this study, the NR3C1 exon 1F promoter region containing 13 CpGs, the human homologue of the rat exon 17, was examined. Using 500 ng of DNA and the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA), sodium bisulfite modification was performed. NR3C1 promoter methylation was determined using the EpiTect methylation-specific PCR (Qiagen, Valencia CA) and quantitative pyrosequencing methods previously described (Oberlander et al., 2008); samples were run in triplicate. Sodium bisulfate-modified, fully methylated referent positive control and fully unmethylated whole genome amplified negative control DNA (Qiagen, Valencia CA) was examined with each batch. Peripheral blood derived DNA that was not sodium bisulfite-modified was included in each pyrosequencing run to control for non-specific amplification. PCR products were visualized and sized on an agarose gel after the run for quality control (FlashGel – Lonza). Pyromark Software (Qiagen) was used to quantify methylation. Our prior work showed high levels of intercorrelation across CpG sites in this region (Tyrka, 2016; Tyrka et al., 2012); for the current paper, we examined mean methylation across the entire region in statistical analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted with SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Mplus Version 7.4 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2012). To normalize the distribution of skewed or kurtotic variables, mtDNAcn and mean NR3C1 methylation were log10-transformed. Individuals were categorized according to presence or absence of early adversity (ncase=138; ncontrol=152). In order to maximize the size of the sample, full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML; (Enders, 2001)) was used to accommodate missing NR3C1 methylation data for two participants. Little’s Missing Completely at Random test (Little, 1988) demonstrated that these data were missing completely at random, χ2(6) = 11.06, p = .09.

Primary hypotheses were tested using regression and path analysis. In our prior work with this sample, early adversity was independently related to higher mtDNAcn (Tyrka et al., 2016a) and lower NR3C1 methylation (Tyrka, 2016). In the present study we therefore tested a mediation model in which the presence or absence of early adversity, predicted mean NR3C1 methylation, which in turn predicted mtDNAcn. Age, sex, and BMI were included as covariates based on prior literature showing effects with adversity, DNA methylation and/or mtDNAcn (Horvath and Raj, 2018; Inoshita et al., 2015; Mendelson et al., 2017). Because study aims were tested using fully saturated models (i.e., 0 degrees of freedom), models provided perfect fit to the data, so fit indices were not examined. To test for hypothesized mediation, we assessed all models using 10,000 bootstrap replicates to obtain bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals for the indirect effects (Mackinnon et al., 2004; Preacher and Hayes, 2008; Shrout and Bolger, 2002).

RESULTS

Subject characteristics are described in Table 1. Demographic characteristics were found to be largely unrelated to mtDNAcn and mean NR3C1 methylation, with the exception that BMI was related to mean NR3C1 methylation (r = −.13, p = .02).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

Total N=290. Depressive disorders include MDD, dysthymia, and depression not otherwise specified. Anxiety disorders include PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, and anxiety disorder not otherwise specified.

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 31.01 (10.75) |

| Sex, N (%) female | 177 (61.0) |

| Race, N (%) white | 241 (83.1) |

| BMI, M (SD) | 26.17 (5.01) |

| College degree, N (%) | 161 (55.5) |

| Oral contraceptive use, N (%) | 39 (13.4) |

| Smokers, N (%) | 29 (10.0) |

| Adversity | |

| Emotional abuse, N (%) | 51 (17.6) |

| Physical abuse, N (%) | 37 (12.8) |

| Sexual abuse, N (%) | 45 (15.5) |

| Emotional neglect, N (%) | 52 (17.9) |

| Physical neglect, N (%) | 32 (11.0) |

| Parental death, N (%) | 36 (12.4) |

| Parental desertion, N (%) | 43 (14.8) |

| Sum adversities, M (SD) | 1.03 (1.43) |

| Psychiatric Disorders | |

| Current Disorders | |

| MDD, N (%) | 13 (4.5) |

| Depressive, N (%) | 25 (8.6) |

| PTSD, N (%) | 3 (1.0) |

| Anxiety, N (%) | 13 (4.5) |

| Past Disorders | |

| MDD, N (%) | 45 (15.5) |

| Depressive, N (%) | 50 (17.2) |

| PTSD, N (%) | 10 (3.4) |

| Anxiety, N (%) | 21 (7.2) |

| Alcohol/Substance, N (%) | 55 (19.0) |

Associations of Early Life Stress, NR3C1 Methylation, and mtDNAcn

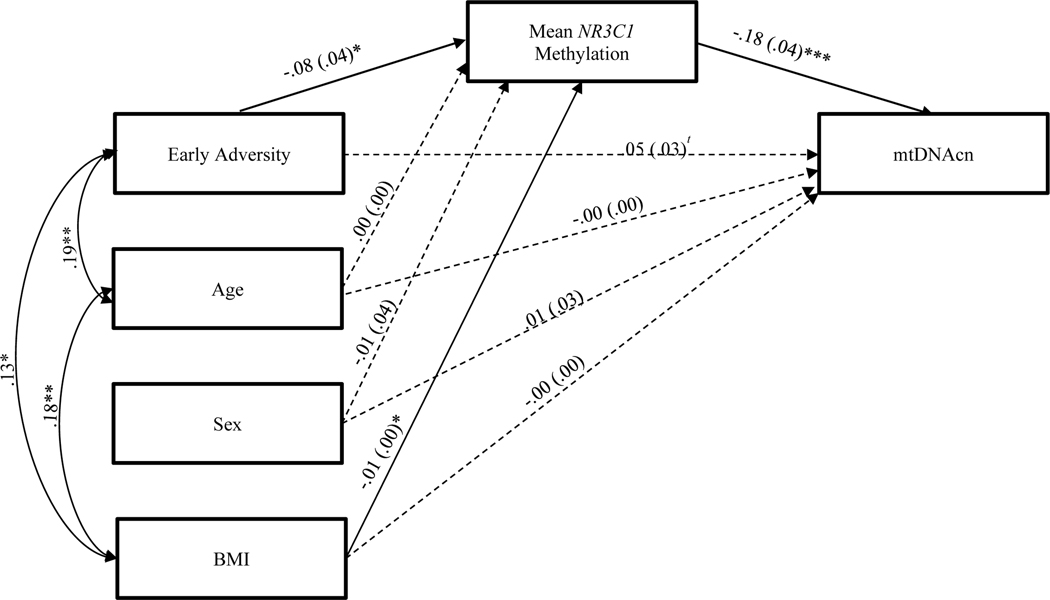

As expected based on our prior report (Tyrka et al., 2016a), regression analyses revealed that early life stress was positively associated with mtDNAcn (B = .06, SE = .03, p = .02). Figure 2 provides the results of the mediation model testing associations of early life stress, NR3C1 methylation, and mtDNAcn, controlling for age, sex, and BMI. Early stress was negatively associated with mean NR3C1 methylation (B = −.08, SE = .04, p = .02), and mean NR3C1 methylation was negatively associated with mtDNAcn (B = −.18, SE = .04, p < .001). Supporting mediation, the indirect path involving early stress, mean NR3C1 methylation, and mtDNAcn was significantly different from zero (95% CI [.002, .030]). In addition to the primary analyses with a priori control for age, sex, and BMI, we also conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether the inclusion of any of the other demographic characteristics (Table 1) altered the pattern of results, and findings were virtually identical with and without inclusion of additional covariates.

Figure 2.

Path model in which mean NR3C1 methylation is specified as a mediator of the association between early adversity and mtDNAcn.

Note t p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Path coefficients are presented in B (SE) format. Dashed line indicates a non-significant association. The indirect effect involving early adversity, mean NR3C1 methylation, and mtDNAcn was statistically significant.

Exploratory Follow-up Analyses: Potential Implications for Psychiatric Disorders

Although the cross-sectional design precludes reliable testing of a four-step indirect effects model including prediction of psychiatric disorder outcomes (Cole and Maxwell, 2003), bivariate associations confirm significant relationships between these variables. History of early life stress was significantly associated with the lifetime presence of a psychiatric disorder (r = .27, p <.001), and in line with our prior work with this sample (Tyrka et al., 2015; Tyrka et al., 2016a; Tyrka et al., 2016b; Tyrka et al., 2012), both NR3C1 methylation and mtDNAcn were significantly associated with lifetime psychiatric disorders (r = −.22, p < .001; r = .17, p = .003, respectively).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this study is the first to examine the pathways between early stress, NR3C1 methylation, and mtDNAcn. The results indicate that NR3C1 promoter methylation mediates the effect of early adversity on mtDNAcn. These results are consistent with data from basic and cellular models showing dynamic regulation of mitochondrial function by the glucocorticoid receptor. In addition, these findings extend previous results by suggesting these mechanisms are relevant to allostatic changes in mtDNAcn observed after early adversity. Exposure to prolonged, severe, or multiple stressors early in life can result in alterations of HPA axis functioning (Bunea et al., 2017; Burke et al., 2005), and epigenetic modification of genes important to HPA axis regulation may be a critical mechanism by which these early exposures can impart physiologic changes (Argentieri et al., 2017; Tyrka et al., 2016c). NR3C1 methylation has been positively correlated with cortisol concentrations (Tyrka et al., 2016b; Yehuda et al., 2015), suggesting an important role of NR3C1 gene methylation in HPA axis regulation.

In this study, we found that lower levels of NR3C1 methylation were associated with higher mtDNAcn. Lower NR3C1 methylation of the 1F promoter region has been associated with increased GR gene expression. The GR can bind to mitochondrial DNA and promote mtDNA replication, increasing mtDNAcn (Clay Montier et al., 2009). The results presented here suggest that increased GR expression after early adversity might be a mechanism by which mtDNAcn increases (Clay Montier et al., 2009; Psarra and Sekeris, 2009); however, further research would be needed to confirm this model. Additionally, activated GR may also increase mtDNAcn by enhancing expression of nuclear genes that regulate mtDNAcn directly or indirectly by modifying oxidative stress pathways (Clay Montier et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013; Psarra and Sekeris, 2009).

These data build on early evidence supporting relationships between early life stress, psychiatric disorders, the neuroendocrine stress response, and mtDNAcn. Previously, we reported greater mtDNAcn in adults with a history of either early stress or psychiatric disorders (Tyrka et al., 2015; Tyrka et al., 2016a). Individuals with a history of both early stress and psychiatric disorders were observed to have the highest mtDNAcn (Tyrka et al., 2016a). Changes in NR3C1 methylation have been reported after early life stress and with psychiatric disorders as well (Tyrka, 2016; Tyrka et al., 2012; Tyrka et al., 2016c), and the results of the present study implicate NR3C1 methylation as a potential mechanism of mtDNAcn increases which may be involved in the development of psychiatric conditions. Our cross-sectional design limits the reliable testing of multiple-effects mediation models; future longitudinal research is needed to test causal models regarding these mechanisms of risk for psychiatric outcomes.

These data are consistent with emerging evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction as a potential biomarker of early stress exposure (Picard et al., 2018; Ridout et al., 2018). Increases in mtDNAcn have been reported after early stress exposure (Cai et al., 2015; Ridout et al., 2018; Tyrka et al., 2016a). Intracellular mtDNAcn is a proxy indicator of mitochondrial biogenesis and a measure of mitochondrial content (Picard et al., 2014) that is dynamically regulated based on the energy demands on the cell (Sun et al., 2016). Consistent with evidence that mtDNAcn is regulated by the inflammatory and oxidative state of the cell to meet energy requirements (Clay Montier et al., 2009), it may be that mtDNAcn dynamically changes depending on stress chronicity and severity. The results of our study add to the evidence that changes in mtDNAcn may reflect allostatic adaptations to stress and be a good marker of allostatic load (Picard et al., 2014; Ridout et al., 2016; Ridout et al., 2018). Such adaptations could impart greater energetic flexibility after stress exposure, but it is unclear if such adaptations are markers of resilience or psychiatric disorder risk; further research in this area is required to clarify this distinction.

While these results suggest a shared mechanistic relationship between early life stress, neuroendocrine function, and mtDNAcn, there are limitations to our study. We do not have measures of GR cellular expression and are using NR3C1 methylation as a proxy for GR protein expression. There are many steps regulating gene expression to protein content, and intracellular regulation of GR availability for cortisol binding is tightly controlled by a number of proteins, including HSP90 and FKBP5 (Binder, 2009); it is possible that the relationships detected here reflect other intracellular processes for which NR3C1 methylation is a proxy. We examined mtDNAcn in this study, which is positively associated with mitochondrial mass and respiratory capacity in healthy tissues (D’Erchia et al., 2015), but it is unclear how variation in mtDNAcn relates to mitochondrial function in our sample. These results were obtained from whole blood, which is a heterogeneous sample, limiting our ability to determine the exact cellular determinants of the changes detected. These limitations provide suggestions for future work to confirm these results.

These data provide preliminary evidence of a mechanistic relationship between NR3C1 methylation, the exposure of early adversity, and mtDNAcn. Future studies focusing on these complex and dynamic processes in regulating the relationship between mtDNAcn, mitochondrial function, and GR are needed to elucidate the role of this pathway in psychiatric disorder risk and development. Such studies may identify new treatment targets for stress-related psychiatric disorders or provide insight to facilitate the development of interventions to prevent the onset of psychiatric disorders after adverse exposures.

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported by NIMH grants MH091508 and MH101107 (ART) and MH068767 (LLC). Dr. Ridout received support from R25 MH101076 and The Physician Researcher Program, Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Dr. Coe received support from T32 MH019927. The study sponsor had no role in this study.

This research was supported by NIMH grants MH091508 and MH101107 (ART) and MH068767 (LLC). Dr. Ridout received support from R25 MH101076. Dr. Coe received support from T32 MH019927.

Disclosures: Dr. Carpenter received clinical trial support from Janssen, Neosync, and Feelmore Labs and consulting income from Janssen and Neuronix. Dr. Price discloses grant/research support from the NIH, is on the data safety and monitoring boards for Baylor University, Cleveland Clinic, Clexio Biosciences, Worldwide Clinical Trials, is a consultant to Wiley, Springer, U Texas (Austin), and Fordham University. All other authors have nothing to disclose. All authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Argentieri MA, Nagarajan S, Seddighzadeh B, Baccarelli AA, Shields AE, 2017. Epigenetic Pathways in Human Disease: The Impact of DNA Methylation on Stress-Related Pathogenesis and Current Challenges in Biomarker Development. EBioMedicine 18, 327–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai RK, Wong LJ, 2005. Simultaneous detection and quantification of mitochondrial DNA deletion(s), depletion, and over-replication in patients with mitochondrial disease. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD 7, 613–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W, 2003. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl 27, 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersani FS, Morley C, Lindqvist D, Epel ES, Picard M, Yehuda R, Flory J, Bierer LM, Makotkine I, Abu-Amara D, Coy M, Reus VI, Lin J, Blackburn EH, Marmar C, Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, 2016. Mitochondrial DNA copy number is reduced in male combat veterans with PTSD. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 64, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder EB, 2009. The role of FKBP5, a co-chaperone of the glucocorticoid receptor in the pathogenesis and therapy of affective and anxiety disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34 Suppl 1, S186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunea IM, Szentagotai-Tatar A, Miu AC, 2017. Early-life adversity and cortisol response to social stress: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry 7, 1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke HM, Davis MC, Otte C, Mohr DC, 2005. Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30, 846–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai N, Chang S, Li Y, Li Q, Hu J, Liang J, Song L, Kretzschmar W, Gan X, Nicod J, Rivera M, Deng H, Du B, Li K, Sang W, Gao J, Gao S, Ha B, Ho HY, Hu C, Hu J, Hu Z, Huang G, Jiang G, Jiang T, Jin W, Li G, Li K, Li Y, Li Y, Li Y, Lin YT, Liu L, Liu T, Liu Y, Liu Y, Lu Y, Lv L, Meng H, Qian P, Sang H, Shen J, Shi J, Sun J, Tao M, Wang G, Wang G, Wang J, Wang L, Wang X, Wang X, Yang H, Yang L, Yin Y, Zhang J, Zhang K, Sun N, Zhang W, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Zhong H, Breen G, Wang J, Marchini J, Chen Y, Xu Q, Xu X, Mott R, Huang GJ, Kendler K, Flint J, 2015. Molecular signatures of major depression. Curr Biol 25, 1146–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay Montier LL, Deng JJ, Bai Y, 2009. Number matters: control of mammalian mitochondrial DNA copy number. J Genet Genomics 36, 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE, 2003. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol 112, 558–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Erchia AM, Atlante A, Gadaleta G, Pavesi G, Chiara M, De Virgilio C, Manzari C, Mastropasqua F, Prazzoli GM, Picardi E, Gissi C, Horner D, Reyes A, Sbisa E, Tullo A, Pesole G, 2015. Tissue-specific mtDNA abundance from exome data and its correlation with mitochondrial transcription, mass and respiratory activity. Mitochondrion 20, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, McEwen BS, 2012. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav 106, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis NP, Yehuda R, 2014. Site-specific methylation changes in the glucocorticoid receptor exon 1F promoter in relation to life adversity: systematic review of contributing factors. Front Neurosci 8, 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, 2001. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychol Methods 6, 352–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA, 2012. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child abuse & neglect 36, 156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB GM, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Benjamin L 1997. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I (SCID-I), Clinical Version. [Google Scholar]

- Francis D, Diorio J, Liu D, Meaney MJ, 1999. Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behavior and stress responses in the rat. Science 286, 1155–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garabadu D, Ahmad A, Krishnamurthy S, 2015. Risperidone Attenuates Modified Stress-Re-stress Paradigm-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Apoptosis in Rats Exhibiting Post-traumatic Stress Disorder-Like Symptoms. J Mol Neurosci 56, 299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner A, Boles RG, 2008. Symptoms of somatization as a rapid screening tool for mitochondrial dysfunction in depression. Biopsychosoc Med 2, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis F, van der Kooij MA, Zanoletti O, Lozano L, Canto C, Sandi C, 2015. Mitochondrial function in the brain links anxiety with social subordination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 15486–15491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, Raj K, 2018. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat Rev Genet 19, 371–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoshita M, Numata S, Tajima A, Kinoshita M, Umehara H, Yamamori H, Hashimoto R, Imoto I, Ohmori T, 2015. Sex differences of leukocytes DNA methylation adjusted for estimated cellular proportions. Biol Sex Differ 6, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabatsiakis A, Bock C, Salinas-Manrique J, Kolassa S, Calzia E, Dietrich DE, Kolassa IT, 2014. Mitochondrial respiration in peripheral blood mononuclear cells correlates with depressive subsymptoms and severity of major depression. Transl Psychiatry 4, e397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klengel T, Binder EB, 2015. Epigenetics of Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders and Gene x Environment Interactions. Neuron 86, 1343–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SR, Kim HK, Song IS, Youm J, Dizon LA, Jeong SH, Ko TH, Heo HJ, Ko KS, Rhee BD, Kim N, Han J, 2013. Glucocorticoids and their receptors: insights into specific roles in mitochondria. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 112, 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, 1988. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Diorio J, Tannenbaum B, Caldji C, Francis D, Freedman A, Sharma S, Pearson D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ, 1997. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. Science 277, 1659–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Zhou C, 2012. Corticosterone reduces brain mitochondrial function and expression of mitofusin, BDNF in depression-like rodents regardless of exercise preconditioning. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 1057–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J, 2004. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivariate Behav Res 39, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoli I, Alesci S, Blackman MR, Su YA, Rennert OM, Chrousos GP, 2007. Mitochondria as key components of the stress response. Trends Endocrinol Metab 18, 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson MM, Marioni RE, Joehanes R, Liu C, Hedman AK, Aslibekyan S, Demerath EW, Guan W, Zhi D, Yao C, Huan T, Willinger C, Chen B, Courchesne P, Multhaup M, Irvin MR, Cohain A, Schadt EE, Grove ML, Bressler J, North K, Sundstrom J, Gustafsson S, Shah S, McRae AF, Harris SE, Gibson J, Redmond P, Corley J, Murphy L, Starr JM, Kleinbrink E, Lipovich L, Visscher PM, Wray NR, Krauss RM, Fallin D, Feinberg A, Absher DM, Fornage M, Pankow JS, Lind L, Fox C, Ingelsson E, Arnett DK, Boerwinkle E, Liang L, Levy D, Deary IJ, 2017. Association of Body Mass Index with DNA Methylation and Gene Expression in Blood Cells and Relations to Cardiometabolic Disease: A Mendelian Randomization Approach. PLoS Med 14, e1002215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, Guinn AS, 2018. Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences From the 2011–2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 States. JAMA Pediatr 172, 1038–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J, Gaspar E, Lopez-Bello G, Juarez E, Alcazar-Leyva S, Gonzalez-Trujano E, Pavon L, Alvarado-Vasquez N, 2013. Increase in nitric oxide levels and mitochondrial membrane potential in platelets of untreated patients with major depression. Psychiatry Res 209, 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicod J, Wagner S, Vonberg F, Bhomra A, Schlicht KF, Tadic A, Mott R, Lieb K, Flint J, 2015. The Amount of Mitochondrial DNA in Blood Reflects the Course of a Depressive Episode. Biol Psychiatry 80, e41–e42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan N, Fenech M, 2011. A quantitative PCR method formeasuring absolute telomere length. . Biol Proced Online 13, 3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM, 2008. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics 3, 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma-Gudiel H, Cordova-Palomera A, Leza JC, Fananas L, 2015. Glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) methylation processes as mediators of early adversity in stress-related disorders causality: A critical review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 55, 520–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard M, Juster RP, McEwen BS, 2014. Mitochondrial allostatic load puts the ‘gluc’ back in glucocorticoids. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10, 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard M, McEwen BS, Epel ES, Sandi C, 2018. An energetic view of stress: Focus on mitochondria. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology 49, 72–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard M, McManus MJ, Gray JD, Nasca C, Moffat C, Kopinski PK, Seifert EL, McEwen BS, Wallace DC, 2015. Mitochondrial functions modulate neuroendocrine, metabolic, inflammatory, and transcriptional responses to acute psychological stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, E6614–6623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF, 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psarra AM, Sekeris CE, 2008. Steroid and thyroid hormone receptors in mitochondria. IUBMB Life 60, 210–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psarra AM, Sekeris CE, 2009. Glucocorticoid receptors and other nuclear transcription factors in mitochondria and possible functions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787, 431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psarra AM, Sekeris CE, 2011. Glucocorticoids induce mitochondrial gene transcription in HepG2 cells: role of the mitochondrial glucocorticoid receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1813, 1814–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezin GT, Cardoso MR, Goncalves CL, Scaini G, Fraga DB, Riegel RE, Comim CM, Quevedo J, Streck EL, 2008. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory chain in brain of rats subjected to an experimental model of depression. Neurochem Int 53, 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout KK, Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR, 2016. The Cellular Sequelae of Early Stress: Focus on Aging and Mitochondria. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 388–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridout KK, Khan M, Ridout SJ, 2018. Adverse Childhood Experiences Run Deep: Toxic Early Life Stress, Telomeres, and Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number, the Biological Markers of Cumulative Stress. Bioessays 40, e1800077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibenhener ML, Zhao T, Du Y, Calderilla-Barbosa L, Yan J, Jiang J, Wooten MW, Wooten MC, 2013. Behavioral effects of SQSTM1/p62 overexpression in mice: support for a mitochondrial role in depression and anxiety. Behav Brain Res 248, 94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N, 2002. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological methods 7, 422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonawski V, Frey S, Golub Y, Rohleder N, Kriebel J, Goecke TW, Fasching PA, Beckmann MW, Kornhuber J, Kratz O, Moll GH, Heinrich H, Eichler A, 2018. Associations of prenatal depressive symptoms with DNA methylation of HPA axis-related genes and diurnal cortisol profiles in primary school-aged children. Development and psychopathology, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streck EL, Goncalves CL, Furlanetto CB, Scaini G, Dal-Pizzol F, Quevedo J, 2014. Mitochondria and the central nervous system: searching for a pathophysiological basis of psychiatric disorders. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria 36, 156–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YA, Wu J, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Su DM, He P, Wang BD, Li H, Webster MJ, Traumatic Stress Brain Study G, Rennert OM, Ursano RJ, 2008. Dysregulated mitochondrial genes and networks with drug targets in postmortem brain of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) revealed by human mitochondria-focused cDNA microarrays. Int J Biol Sci 4, 223–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N, Youle RJ, Finkel T, 2016. The Mitochondrial Basis of Aging. Mol Cell 61, 654–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki MM, Bird A, 2008. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet 9, 465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed SA, Nemeroff CB, 2017. Early Life Stress, Mood, and Anxiety Disorders. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JD, Alt SR, Cao L, Vernocchi S, Trifonova S, Battello N, Muller CP, 2010. Transcriptional control of the glucocorticoid receptor: CpG islands, epigenetics and more. Biochemical pharmacology 80, 1860–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Carpenter LL, Kao HT, Porton B, Philip NS, Ridout SJ, Ridout KK, Price LH, 2015. Association of telomere length and mitochondrial DNA copy number in a community sample of healthy adults. Exp Gerontol 66, 17–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Parade SH, Price LH, Kao HT, Porton B, Philip NS, Welch ES, Carpenter LL, 2016a. Alterations of Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number and Telomere Length With Early Adversity and Psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry 79, 78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Parade SH, Welch ES, Ridout KK, Price LH, Marsit C, Philip NS, Carpenter LL, 2016b. Methylation of the leukocyte glucocorticoid receptor gene promoter in adults: associations with early adversity and depressive, anxiety and substance-use disorders. Transl Psychiatry 6, e848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Price LH, Marsit C, Walters OC, Carpenter LL, 2012. Childhood adversity and epigenetic modulation of the leukocyte glucocorticoid receptor: preliminary findings in healthy adults. PLoS One 7, e30148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Ridout KK, Parade SH, 2016c. Childhood adversity and epigenetic regulation of glucocorticoid signaling genes: Associations in children and adults. Dev Psychopathol 28, 1319–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachon DD, Krueger RF, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D, 2015. Assessment of the Harmful Psychiatric and Behavioral Effects of Different Forms of Child Maltreatment. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 1135–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Ren Z, Zheng J, Feng L, Li D, Gao K, Zhang L, Liu Y, Zuo P, 2016. 5-(4-hydroxy-3-dimethoxybenzylidene)-rhodanine (RD-1)-improved mitochondrial function prevents anxiety- and depressive-like states induced by chronic corticosterone injections in mice. Neuropharmacology 105, 587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Flory JD, Bierer LM, Henn-Haase C, Lehrner A, Desarnaud F, Makotkine I, Daskalakis NP, Marmar CR, Meaney MJ, 2015. Lower methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene promoter 1F in peripheral blood of veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 77, 356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Li H, Hu X, Benedek DM, Fullerton CS, Forsten RD, Naifeh JA, Li X, Wu H, Benevides KN, Le T, Smerin S, Russell DW, Ursano RJ, 2015. Mitochondria-focused gene expression profile reveals common pathways and CPT1B dysregulation in both rodent stress model and human subjects with PTSD. Transl Psychiatry 5, e580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]