Abstract

In the past decades, donors and development actors have been increasingly mindful of the evidence to support long-term, dynamic social norms change. This paper draws lessons and implications on scaling social norms change initiatives for gender equality to prevent violence against women and girls (VAWG) and improve sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), from the Community for Understanding Scale Up (CUSP). CUSP is a group of nine organisations working across four regions with robust experience in developing evidence-based social norms change methodologies and supporting their scale-up across various regions and contexts. More specifically, the paper elicits learning from methodologies and experiences from five CUSP members – GREAT, IMAGE, SASA!, Stepping Stones, and Tostan. The discussion raises political questions around the current donor landscape including those positioned to assume leadership to take such methodologies to scale, and the current evaluation paradigm to measure social norms change at scale. CUSP makes the following recommendations for donors and implementers to scale social norms initiatives effectively and ethically: invest in longer-term programming, ensure fidelity to values of the original programmes, fund women’s rights organisations, prioritise accountability to their communities and demands, critically examine the government and marketplace’s role in scale, and rethink evaluation approaches to produce evidence that guides scale-up processes and fully represents the voices of activists and communities from the Global South.

Keywords: scale-up, social norms, social change, gender equality, violence against women, sexual and reproductive health and rights

Résumé

Ces dernières décennies, les donateurs et les acteurs du développement ont été de plus en plus attentifs aux données susceptibles de soutenir un changement dynamique et à long terme des normes sociales. Cet article tire les leçons et les conséquences sur l’élargissement des initiatives de changement des normes sociales pour l’égalité de genre en vue de prévenir la violence contre les femmes et les filles et d’améliorer la santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs, de la Community for Understanding Scale Up (CUSP). CUSP est un groupe de neuf organisations qui travaillent dans quatre régions et possèdent une solide expérience dans l’élaboration de méthodologies de changement des normes sociales à base factuelle et dans le soutien à leur élargissement dans différentes régions et contextes. Plus précisément, l’article utilise des enseignements issus de méthodologies et d’expériences de cinq membres de CUSP – GREAT, IMAGE, SASA!, Stepping Stones et Tostan. La discussion soulève des questions politiques autour de la scène actuelle des donateurs, notamment ceux qui sont placés de façon à assumer la direction du déploiement de ces méthodologies, et le paradigme actuel de l’évaluation pour mesurer le changement des normes sociales à l’échelle. CUSP fait les recommandations suivantes aux bailleurs de fonds et aux responsables de la mise en œuvre pour élargir efficacement et éthiquement les initiatives sur les normes sociales: investir dans une programmation à long terme, garantir la fidélité aux valeurs des programmes originaux, financer les organisations de défense des droits des femmes, donner la priorité à la redevabilité envers leurs communautés et leurs exigences, examiner de manière critique le rôle des autorités gouvernementales et du marché à l’échelle, et repenser les approches d’évaluation pour produire des données qui guident les processus de déploiement et représentent pleinement les voix des activistes et des communautés du Sud global.

Resumen

En las últimas décadas, los donantes y actores en el campo de desarrollo han sido cada vez más conscientes de la evidencia que apoya el cambio dinámico de normas sociales a largo plazo. Este artículo se basa en las lecciones e implicaciones de ampliar las iniciativas de cambio de normas sociales a favor de la igualdad de género para prevenir la violencia contra mujeres y niñas y mejorar la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos (SDSR), de la Comunidad para Entender Ampliación (CUSP, por sus siglas en inglés). CUSP es un grupo de nueve organizaciones que trabajan en cuatro regiones, con extensa experiencia creando metodologías basadas en evidencia para el cambio de normas sociales y apoyando su ampliación en diversas regiones y contextos. En específico, este artículo suscita aprendizaje de las metodologías y experiencias de cinco integrantes de CUSP – GREAT, IMAGE, SASA!, Stepping Stones y Tostan. La discusión plantea interrogantes políticas en torno al panorama actual de donantes, incluidos los que están preparados para asumir el liderazgo para ampliar esas metodologías, y el paradigma de evaluación actual para medir el cambio de normas sociales a escala. CUSP hace las siguientes recomendaciones a donantes y ejecutores para ampliar las iniciativas de cambio de normas sociales de manera eficaz y ética: invertir en programas a largo plazo, asegurar fidelidad a los valores del programa inicial, financiar organizaciones por los derechos de las mujeres, priorizar la rendición de cuentas a sus comunidades y exigencias, examinar críticamente el rol del gobierno y del mercado en escala, y reformular las estrategias de evaluación para producir evidencia que guíe los procesos de ampliación y represente plenamente las voces de activistas y comunidades del Sur Global.

Introduction

The Community for Understanding Scale Up (CUSP) is a working group of nine organisations* with robust experience in developing and scaling social norms change methodologies across regions and contexts. CUSP originated in 2016, when Raising Voices and Salamander Trust began informal conversations about challenges and opportunities as their methodologies (SASA! and Stepping Stones, respectively) were being scaled. In response, they created CUSP, to draw on these collective experiences to promote gender equality through prevention of violence against women and girls (VAWG) and expansion of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR).

CUSP represents a unique perspective of successful evidence-based methodologies from organisations that have worked autonomously and/or with partners to implement, adapt, and/or scale their programmes. Based on growing demand for social norms change programming at scale, CUSP has been wrestling with critical issues regarding what it takes to scale social norms change methodologies effectively and ethically, challenges and opportunities bringing innovations to scale, and political implications of the donor and development landscape’s growing emphasis on scale. CUSP’s 2017 brief “On the Cusp of Change: Effective scaling of social norms programming for gender equality” provided advice on how to take social norms programming to scale.1 We are optimistic about the potential and positive impact of scaling social norms initiatives, and our intention is to inform future scale-up to strengthen the integrity and effectiveness of such efforts.

Based on these insights into what supports or undermines effective scaling, CUSP offers here a political analysis of the current funding and development aid landscape impacting scale, including the current aid paradigm; fidelity to original programme structures; limited accountability to communities, with a focus on results over process; implementation under government and for-profit agencies; and an evaluation framework which does not fully meet the needs of social norms change programmes at scale. Our shared experiences have helped us uncover critical pitfalls, ones that we hope will guide policy and funding to end harmful practices and foster healthier, safer communities.

Background on scale and social norms

Defining scale-up

While many definitions of scale-up exist, the World Health Organisation (WHO)/ExpandNet Consortium describes scale-up as “deliberate efforts to increase the impact of … innovations successfully tested in pilot or experimental projects so as to benefit more people and to foster policy and programme development on a lasting basis”.2 This definition, although originally designed for health care, has largely been expanded to other sectors, including education, agriculture, and gender equality. ExpandNet defines an innovation as a practice, or set of practices, including processes that support implementation, that are new or perceived as new in a particular context. See Box 1 for details.

Box 1. Expandnet’s four types of scale3 .

horizontal scaling up (expansion or replication) – innovations extended geographically or to expanded/new populations;

vertical scaling up (policy/political/legal/institutional scaling) – formal government decision to adopt innovation via policies;

functional scaling up (diversification) – “grafting”, or adding interventions/components to an existing innovations package;

spontaneous diffusion of innovations – when the innovation addresses a need within the programme or when a key event draws attention to a need.

Context

Funders have long been interested in testing innovative programmes, selecting those of high impact (and low cost) to adapt and scale for more impactful reach through increased coverage and/or resources.4 Successful scale-up can face many challenges, including securing sustainable funding and maintaining programming quality.

The initiatives discussed in this paper, designed by five CUSP members, are a powerful set of approaches backed by rigorous evidence and, collectively, over 120 years of practice-based learning. Table 1 provides a brief overview of the programmes and their respective evaluations. For further insight into experiences with scale – both successful and challenging – see CUSP’s 2018 Case Study Collection.5

Table 1. Overview of five CUSP programmes.

| Initiative | Description | Period of evaluated programme implementation | Evaluation design | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GREAT | GREAT is set of participatory activities designed to support girls’ and boys’ growth into healthy adults and promote non-violence and SRHR in Northern Uganda. | 14 months from September 2015 to November 2016 | Quasi-experimental (pre/post-test with control) | Improved attitudes and behaviours around gender equity, partner communication, family planning use, and gender-based violence (GBV).6 |

| IMAGE | The Intervention with Micro-finance for AIDS and Gender Equity (IMAGE), is a combined micro-finance, HIV and GBV training, and community outreach intervention in South Africa. | 4 years from June 2001 to March 2005 | Randomised controlled trial | Relative to matched controls, IMAGE participants showed reduced risk of physical and sexual violence, increased self-confidence, ability to challenge gender norms, autonomy in decision-making, and to take collective action.7 |

| SASA! | SASA! is a holistic, community mobilisation approach for preventing violence against women and HIV. | 2 years, 8 months over four years, from May 2008 to December 2012 | Cluster randomised controlled trial | Community-level impacts on reduced risk of intimate partner violence against women, decreased social acceptability of IPV against women among women and men, and reduction of sexual concurrency among men.8 |

| Stepping Stones | Stepping Stones is a holistic, rights-based programme, designed to address the many and complex issues facing communities in relation to social norms change around violence against women, SRHR and attitudes and practices towards people with HIV. | About 50 h over 6–8 weeks from March 2003 to March 2004. | Cluster randomised controlled trial | Improved reported risk behaviours in men, including a lowered proportion of men reporting perpetration of intimate partner violence, a reduction in transactional sex and in problem drinking.9 |

| Tostan | Tostan’s Community Empowerment Programme is a human-rights-based nonformal education programme that empowers communities to lead their own development. | 30 months, over 3 years from October 2000 to October 2003 | Quasi-experimental design | Improved knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour among men and women around respect for human rights, improvement of hygiene and health, and specifically, a reduction in support for and practice of female genital cutting (FGC) and gender-based violence.10 |

Scaling social norm programmes: evidence-based learning

CUSP believes that meaningful social norms change occurs through community-driven efforts guided by a philosophy that focuses on likely benefits of change for all. Given challenges in undoing and recreating centuries-old norms, scaling norms change is rarely a simple or linear process, as the evolving literature shows. Successful scale-up involves a well-defined, proven practice expanded through a purposeful systems approach which fully engages stakeholders to apply active implementation supports, including monitoring and evaluation (M&E), to ensure that fidelity to the essential elements of the innovation and its core values are maintained.2,3,11,12

In relation to proven effectiveness, an exploration of women and girl-focused HIV interventions in almost 100 countries from 2005 to 2012, “What works for women”, considers overarching principles and strategies for reducing HIV among women, highlighting links between HIV, VAW, and social norms change.13 The review identifies gender norm transformation and strengthening an enabling environment as key components of promising strategies, noting robust evidence to support strategic scale-up of many of the evidence-based programmes they cite.13

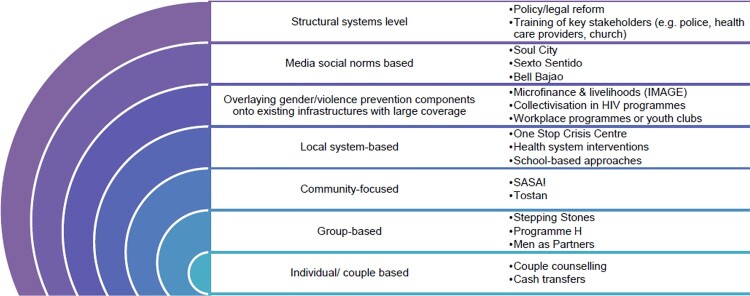

An evidence review of approaches to scale up VAWG programming14 provides a meta-analysis of effective VAWG scale-up approaches, including techniques to assess cost-effectiveness. The synthesis identified effective and replicable models across the ecological framework, including many CUSP members’ programmes (Figure 1). The left column indicates the ecological framework level; the right describes corresponding interventions with proven effectiveness. The review revealed that those with a multi-sectoral approach, multiple platforms and service delivery sites were more effective in scaling up VAWG prevention.

Figure 1.

Intervention models according to the ecological framework13

The programmes in Figure 1 achieving impact at scale have multiple similarities. Primary among them were core principles for ensuring that social norms programmes for gender equality were safe, ethical, and effective, based on lessons from implementation of community initiatives around VAW prevention, power, and HIV. Box 2 summarises guiding principles for social norms programmes, based on evidence from diverse sources that have been useful in our experience.1,14–22

Box 2. Guiding principles gathered from a selection of social norms programmes.

Support theory- and evidence-informed innovations1,17,19,20,22,23

Promote personal and collective critical reflection through aspirational programming1,19

Support and invest in staff and community activists/facilitators14,18,21

Work across the ecological model and change matrixsup1,17,19

Original organisation* to provide technical support19

Use a whole-society approach (as opposed to e.g. single-sex interventions)1,15,16

* “Original organisation” refers to the organisation that developed the methodology

Despite evidence that such guiding principles show results, CUSP members have faced political challenges that led us to discuss where breakdowns occurred between principle and practice; and to assess broader policy implications for scaling social norms programmes.

Some current investments in social norms initiatives at scale

Steady investment in social norms change programming to foster gender equality over several years at national, regional, and global levels motivated CUSP’s collaboration. Examples of investments include:

The Global Fund to Fight HIV, TB, and Malaria has prioritised Promoting and Protecting Human Rights and Gender Equality. In this funding cycle, the Global Fund is providing over $54 million in matching funds for 13 countries specifically focusing on adolescent girls and young women, including through prevention of gender-based violence (GBV) and addressing harmful gender norms.24

The DREAMS project, a public-private initiative under the US government-led PEPFAR, is a $385 million partnership dedicated to reducing HIV among adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa. Among its interventions, DREAMS addresses structural barriers of HIV acquisition, including GBV and gender inequality.

The Spotlight Initiative to eliminate violence against women and girls, a UN/EU Partnership, is a 500 million EUR global initiative. Spotlight emphasises promotion of gender equitable social norms, attitudes, and behaviours to prevent VAWG and harmful practices.

Many of these donors have funded or are currently funding scale-up of methodologies created by CUSP members in their regional and global strategies, with or without our input. For example, DREAMS has adapted and implemented both Stepping Stones and SASA! in Lesotho, South Africa, Uganda, and elsewhere. DFID’s SURGE Project supports SASA! implementation in Uganda, while USAID funded GREAT in Northern Uganda. Various international organisations and UN agencies have also funded CUSP programmes, including ActionAid, International Rescue Committee, MRC, PACT, Plan International, PSI, JHU CCP, URC LLC, UNDP, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNFPA, and UN Women.

While gender equality is intrinsic for human rights, there is also clear evidence that it contributes to economic growth25 and greater peace and stability,26 catalysing further interest from state and non-state actors to pursue social norms change. With expanding investments come responsibilities to develop policy and funding strategies that ensure safe, ethical, and responsible scale-up, through maintaining fidelity to the principles, mechanisms, and core values of original programmes. Through the group’s continuous collaboration since 2016, CUSP has discussed and explored our own experiences, providing deeper scrutiny into policy and programming implications for scaling our respective methodologies globally.†

Lessons for implementation at scale

Short-term projects are not well-placed to sustain change and maintain fidelity

Evidence-based social norms change programmes, including CUSP programme methodologies, are process-oriented, requiring sustained, coordinated programming that engages the whole of society in a principled and reflective approach. However, current development and humanitarian investment strategies are predominantly project-based, with short timeframes, single-focus outcomes and apolitical frameworks. Rather than transforming systems of unequal power relations, this approach can be ineffective27 and unethical for communities when scaling social norms change programmes.

Social change takes time; the journey itself is what produces results. Yet, donors continue to fund consecutive, results-focused projects within the same community: a model which produces less impact, becomes increasingly expensive over time, can demoralise a community and undermine the emergence of a politicised population of agents, rather than “beneficiaries”, of change. While sustained community mobilisation can, in the short term, seem costly, the results are far-reaching and substantive.28

In a West African country, an organisation chose to implement an abridged version of Tostan’s programme, omitting key exercises by compressing the time the classes were offered and using facilitators from outside of the community. The adaptation violated three core principles that ensure fidelity1: respecting the sequence embedded in the curriculum; time to assimilate, discuss new information and share with adopted learners and the extended community; and availability of facilitators for more deeply exploring topics. Although the partner judged implementation to be successful, Tostan decided not to scale its programme unless its core principles were followed and chose not to make its curricula publicly available.

Trying to squeeze meaningful programming into the current funding paradigm can have devastating consequences for the communities. Because funding is sometimes curtailed before realising the full scope of the initiative, programmes are halted, processes of change upended, and quality, safety, and accountability compromised. For example, IMAGE was scaling up with a partner in South Africa, undertaking a year’s worth of foundational work that included stakeholder engagement, a feasibility assessment, programme planning, design, curriculum adaptation, staff training, and establishing an M&E system. When preparation was complete, a change in donor personnel affected funding continuity. The donor withdrew funding, ceasing implementation because they failed to recognise the importance of the foundational work, wanting immediate results instead.5

We suggest that donors sufficiently invest in the process at the onset of social norms change scale-up, recognising its long-term goals and potential for diffusion, and thereby enabling longer-term benefits through profound changes in social norms. CUSP also recommends that donors ensure fidelity to the original programme’s core values, structure, and principles, to improve its likely effectiveness, as designed by its creators.

Prioritise funding of feminist organisations

In addition to the challenge of securing sustained funding for authentic community engagement, the accountability process remains top-down – whereby local organisations are accountable to funders (if they are funded), and not vice versa. This is at odds with social norms change initiatives that call for analysing and deconstructing patriarchal systems. Consequently, privileging women’s rights/feminist organisations in leading programming at scale is a political act, because upending current hierarchies changes power dynamics and models mutual accountability. In general, community members are rarely given the chance to develop a public voice that is not only elicited but also valued. This is particularly apparent in the insufficient funding of feminist organisations and, therefore, limited accountability to their priorities.

A global poll in 2011 revealed that 48% of women’s organisations had never been recipients of core funding,‡ and 52% never received multi-year funding.29 While donors are increasingly vocal about “feminism” and “investment in gender equality,” many are simply not directly funding non-governmental women’s organisations,§ instead supporting large, and often bureaucratic INGOs, governments, and international development contractors (IDCs),** through an instrumentalist framing of “women’s rights and empowerment”.30 †† This technocratic approach further marginalises women, minimising their participation and leadership.

Furthermore, requirements by some funders, especially those from the Global North, undermine the focus of feminist organisations on local or national action, or even disqualify them from receiving funds, in favour of large organisations with systems and experience focused on managing large-scale funding.31,32. Feminist Global South-based organisations may not have these structures, and are thereby unintentionally marginalised, thus widening the Global North/South divide and tasking organisations and their technocrats with solving problems for women, rather than with women.

Yet feminist organisations are critical in recognising rights, supporting overlooked marginalised groups, and understanding the nuances of women’s priorities in their contexts.33 Most of the CUSP methodologies, for example, were designed by feminist organisations through core funding, where they had the time and freedom to experiment, learn, and organically develop the methodologies.

Feminist organisations work for progressive policy change, specifically around VAW; in fact, feminist movements are the largest driving factor in institutionalising women’s rights in their countries.34 These organisations not only hold legitimacy and expertise; their programming is more likely sustained with meaningful leadership and ownership within communities themselves.

By contrast, initiatives predicated on short-term, project-based funding, with social norms change programming designed from the outside, are a common scale-up pitfall and can create unintended harm. This is especially apparent when a new norm is quickly adopted among some community members, when the majority have not been engaged: early adopters can face severe backlash.22 Furthermore, others in the community may then be more hesitant to adopt the new norm. Instead, community members, supported by an organisation, must “lead the movement for change”22 themselves.

Ever-shrinking space for civil society globally and nationally, evidence, and our collective experiences indicate that donors would best achieve their overall VAW-reduction aims by sustained core and programme funding to feminist organisations in the Global South. Donors would best ensure that these same organisations shape scaling up strategy and implementation and are meaningfully included in decision-making processes, at strategic and practical levels.

Question who leads scale

While government engagement may be one indicator of scale-up success, the optimal level and nature of state engagement remains unclear, given sensitive issues like power, violence, and equality. The enduring and deeply political question to consider is whether governments can truly own and lead programmes that aim to transform social norms, when most are gatekeepers of such norms.

In addition to government entities, IDCs are often considered appropriate actors to scale social norms change and increasingly bid for such work.28,35 Their for-profit mandates inherently promote top-down, results-focused projects: a misfit of values and approaches for social norms change, process-based programming.

Funders have deliberately chosen to task governments and IDCs with scaling social norms change initiatives (and other international development programmes) over feminist movements, in hopes of a politically neutral approach. However, challenging power inequities individually and structurally is an inherently political act that aims to upend traditional power structures (including those based on sex, race, geopolitics, religion, wealth, etc.). “Adopting [feminism] in substance would require a relinquishing of power by aid professionals, elite women holding high-level political positions, and local intermediaries that deliver aid”.36 While “empowerment” programmes and feminist slogans are appropriated in reports and methodologies, the hierarchy of power within a patriarchal structure persists in such top-down processes.

As an international collective of organisations dedicated to social norms change, CUSP has varied experiences of engaging with government and IDCs in scale-up. For example, GREAT’s horizontal scale-up was coordinated by local government in Northern Uganda through regular check-ins and reflection meetings with implementing organisations to ensure coverage of all activity components in each community. Vertical scale-up was supported by a resource team of implementers, GREAT programme originators and representatives of the Ministries of Health, Education and Gender, Labour, and Social Development. However, local government coordination effectiveness varied across districts, through mixed motivation and capacity of local officials, staff turnover, and available resources. Furthermore, GREAT expansion was not supported at national level due to conflicts with broader national and donor priorities.

In addition, local government adaptation and scaling of SASA! in Busoga, Uganda encountered considerable challenges. SASA! is designed to foster activism and inspire change in individual and community-level power dynamics, yet government officials frequently represent and maintain the status quo, creating an inherent conflict between the programme’s goals and those leading it. The role of government officials does not typically include discussing personal issues around power, violence, and gender, particularly when duty bearers could use their power to take punitive action and as individuals often perpetuate the norms that SASA! seeks to change. This can drive issues underground rather than promote deep and transformative change. SASA!’s original and intentional design places community members at the heart of questioning power and creating change and holding community leaders and institutions to account.

Programmes designed by CUSP members have repeatedly stressed what is essentially the political importance of clarifying and aligning values regarding gender equality and equity in adaptation, implementation, and scale. To transform the status quo and redistribute power more equitably, organisations must start from within. By contrast, governments and IDCs often guarantee the status quo and are frequently distrusted by communities as they are viewed as “officialdom and bureaucracy.” Their very structures are politically defined as patriarchal and often male-dominated, yet simultaneously, they couch their development interventions as apolitical. It is unclear whether governments and IDCs are willing to genuinely address the political nature of the power dynamics in their own organisations, with their resultant biases. It is crucial that they ensure that feminist organisations are leading change at scale.

Diversify evaluation methods to respond to the complexities of social norms change at scale

Planned efforts to scale social norms change require robust evidence of norms change initiatives and understanding of implementation challenges, change pathways, and mechanisms of change. This knowledge informs what will work, for whom, in what settings, and whether scale-up is feasible with the available resources and political will. However, there is little evidence to shed light on these questions, due in part to the lack of validated social norms measures and the tendency to conflate attitudes with norms. Indeed, current research and evaluation practice falls short of providing the insights needed to guide the scale-up of social norms programmes, largely due to the nascent state of social norms measurement and an over-reliance on randomised control trials (RCTs).22,23

Social change demands “complex, multi-faceted, and often multi-sectoral interventions”,37 which frequently require non-linear research approaches to understand change processes. Translating complex social norms theory into practical approaches is a rapidly evolving field, with increasing recognition that better measures are needed to assess social norms changes.38,39 Few evaluations of social norms programmes have included rigorous social norms measures, often relying on impact studies, including some CUSP methodologies, that use individual attitudes and beliefs as proxies.40 This has resulted in a lack of clarity around the ways that programmes function and what is required to shift norms and behaviours and thus, a weak evidence base for their expansion.

As leadership of scale-up remains in the hands of those already in power, the evaluation agenda also serves to maintain current hierarchies. Yet, RCTs are designed to evaluate interventions isolated from the “noise of social context”41 and rarely take place under conditions which would be typical of scale-up. They are generally conducted on a programme’s ideal version, under carefully controlled conditions with enough human and financial resources. Many CUSP initiatives have been assessed through an RCT, partnering with academics in the Global North. While RCTs can be a useful assessment, if this is the “gold standard” requirement for programmes to go to scale, we are limiting innovation due to the inflexibility of evaluation methods that may be better placed to assess the nuances of social norm change. Therefore, we encourage researchers and practitioners to expand the criteria by which social norms change interventions are deemed worthy of investment and scale.

A study on barriers to scaling health interventions in low- and middle-income countries suggested an intermediate phase between RCT and scale-up, arguing that many scale-up strategies are overly dependent on evaluation methods which do not encourage reflexive learning through expansion or for replicability in other contexts.12 RCTs alone do not provide adequate information on context or complexity to guide scale-up, primarily because the programmes are not being assessed for scale but for efficacy of the methodology. Further information is needed to guide adaptation and scale-up, especially identifying the critical mechanisms/processes and political context that make a programme effective. While several other evaluation approaches – such as whole systems action research, realist evaluation, qualitative comparative analysis, and outcome mapping – are better suited to address the complexity of social change, donors and academics still look to RCTs as the primary evaluation tool.20,41

Consequently, to meet demand for RCT-based evidence as a prerequisite to scale-up, interventions are developed in response to researchers’ and donors’ priorities, rather than those of women and their communities. Lack of access to RCTs thus disempowers activists, their organisations, and researchers from the Global South, who often become sidelined in research processes and evaluation decisions. This may create interventions with a narrow focus, removed from communities’ complex realities, which do not alter the systems of inequality embedded within economic, social, and political structures. This dynamic prioritises researchers over community activists– much to the detriment of civil society and social movements. When researchers from the Global North approach their work from a seemingly politically neutral standpoint, disregarding their own identities and power dynamics between themselves/their institutions and their “subjects,” they reproduce the same inequalities they seek to understand.42,43

CUSP initiatives have also had RCT-related challenges. For example, the 2008 Stepping Stones RCT revealed reductions in: IPV by male participants, casual sex, problem drinking, and herpes simplex. However, there was no statistically significant reduction in HIV incidence. Because of the high cost of the biomedical dimensions of RCTs, the programme was only conducted with the two youth peer groups, thereby excluding the group (of older men) from whom younger women more often contract HIV, as well as omitting the opportunity to improve cross-generational relationships.44 ‡‡ Thus, this limited RCT version was unable to truly assess the programme’s overall effectiveness in reducing HIV incidence.

In the case of SASA!¸ the programming evaluated by an RCT is often not what is replicated through the adaptation and implementation process. With demand for scale, donors and partners are cutting fundamental principles, minimising training and mentoring, reducing frequency of activities and reducing project timeframes recommended in SASA! while expecting the same results.

Favouring programmes that worked well under pilot conditions in an RCT without considering the implications of scale-up and the political realities grounding social norms can be a misuse of resources and may limit the development and spread of programmes cultivated organically within communities. “Evidence-based” does not always mean “evidence-based-at-scale”.

Going forward

In light of CUSP experiences, we encourage funders, researchers, and governments to recognise the political dimensions to social norms change programming. We offer the following recommendations to develop policy and investment strategies for scaling social norms change.

-

Invest in longer term, sustainable social change processes

Fund transformative, sustainable programming that addresses core drivers of gender inequality. Longer-term, more substantial investment in communities can reap rewards, ensuring meaningful change, in line with the SDGs. Furthermore, when programming is designed and implemented within a feminist frame, community members are equipped with the critical reflection and activism skills necessary to inspire engagement across a range of issues, creating diffusion and inspiring a domino effect of socio-political transformation.

-

Maintain fidelity to change mechanisms

CUSP programmes have deliberate, successive “staircase” components that are integral to creating and sustaining social change. Neglecting, rearranging, or curtailing these elements can compromise the programme’s success, while also potentially harming the community. Adaptation is critical: yet fidelity to core principles, values, structures, and change processes maintains the integrity and potential impact of programming.45

-

Support feminist organisations

Htun & Wheldon35 established that a strong feminist movement is singularly important for progressive VAW policy and programming. Yet the Association of Women in Development (AWID)'s research suggests that feminist organisations have been chronically underfunded for 20 years and continue to lose funding, to INGOs, government, and the marketplace.28 When implementing and scaling social norms methodologies, donors should prioritise investment in feminist organisations, skilled in holistic whole-community approaches to facilitating pathways for positive social change, as lead grantees.

-

Prioritise community accountability and demand

Listen to women in their communities—social norms change is sensitive and potentially dangerous work, especially for women. Determining in which communities to scale, ensuring their meaningful input from the outset and accountability to communities throughout, can avoid harm and avert risky or futile programming.

-

Critically examine the government and marketplace’s roles in scale

Be mindful of which individuals and institutions benefit from the status quo, and whose principles may inherently be at odds with social norms transformation. CUSP’s experiences with unsuccessful scale often included a lack of explicit internalised gendered principles by the donor, government, and/or the implementing organisation. Donors should reconsider funding technical organisations to engage in feminist, political work on social justice which may not fit well with their own organisational culture. Global inequality was created through political means and must be similarly challenged in a political manner.46

-

Diversify evaluation methods

Think beyond linear evaluation designs such as RCTs and improve social norms measures to produce the evidence needed to determine what is worthy to scale and how to do so. While RCTs provide important data, they are not generally well-suited to provide critical information to inform scale-up of complex social change processes in dynamic macro-political and social contexts. What works, how it works, for whom, under what circumstances are all critical questions.20,47

Conclusion

We are on the cusp of change. We have some evidence on what works to change social norms at scale. Cusps are precarious places; they can be on the edge of success – or on the edge of an abyss. Through this paper, we seek to guide policies, funding and programming toward success.

Social norms change programming for gender equality that addresses VAW, and women’s SRHR more generally, is a process toward realising social – and political – justice. Social norms change initiatives that promote human rights and a gender transformative civil society also foster an enabling environment for communities, leading to a more equitable, non-violent, peaceful, and profitable society.22,23 We have seen the potential of these programmes to generate transformational change1; yet, to achieve this, scaling up must be done in an overtly political, ethical, and intentional manner,48 drawing on lessons learned from practice, and, ideally, under the leadership of feminist organisations already pioneering sustainable change in their communities. While there are technical demands to scaling social norms change programmes, we must recognise and address the political nature of dismantling systems of oppression and reflect on how current initiatives are led by those intent on maintaining the status quo. Social norms change rests in the hands of the communities who have had meaningful opportunities to critically analyse, dialogue, assert their own values and create their own future. Ultimately, all our efforts should be committed to scale-up processes which prioritise the visions, priorities, and safety of women and communities.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Amy Bank, Mona Mehta, Tina Musuya, and Angelica Pino for reviewing the article and for the rich discussions that developed these ideas.

Footnotes

The Center for Domestic Violence Prevention (CEDOVIP), IMAGE Programme, the Institute for Reproductive Health at Georgetown University, the Oxfam initiated “We Can” campaign, Puntos de Encuentro, Raising Voices, Salamander Trust, Sonke Gender Justice, and Tostan.

CUSP has presented at the Sexual Violence Resource Initiative Forum 2017, UN Women’s 2018 Asia Pacific Regional Meeting on Violence against Women and Girls: Prevention and Social Norms Change and World Health Organization’s Global Launch of the RESPECT Framework.

Core funding covers financial support to an organisation's strategic vision rather than donor-defined project implementation, and can include salaries, office costs, equipment, IT, accounting, planning, fund-raising etc.

These can be community-based, national, regional or global groups.

IDCs are private consulting agencies with profit-making mandates.

An instrumentalist approach to women’s rights (i.e. investing in women to yield economic growth) rather than an intrinsic rights-based approach (protecting women’s safety and promoting their well-being as a human right).

‘Cross-generational’ here means, for instance, either boyfriend/girlfriend relations between younger women aged about 17 and older boyfriends of about 23 - and/or older sugar daddies aged around 35 or more. Both relations can be/are likely to be less or more transactional in structure.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Leah Goldmann http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2278-7353

Rebecka Lundgren http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9607-5722

Alice Welbourn http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0829-3122

Diane Gillespie http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8005-9664

Ellen Bajenja http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1434-2859

Lufuno Muvhango http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0894-1633

Lori Michau http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7869-0812

References

- 1.CUSP (2017). On the cusp of change: Effective scaling of social norms programming for gender equality, Community for Understanding Scale Up.

- 2.ExpandNet, WHO Practical guidance for scaling up health service innovations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simmons R., Fajans P., Ghiron L, editors. Scaling Up health service delivery: from pilot innovations to policies and programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43794/1/9789241563512_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangham LJ, Hanson K.. Scaling up in international health: what are the key issues? Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(2):85–96. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CUSP CUSP 2018 Case Study Collection, Community for Understanding Scale Up; 2018. Available from http://raisingvoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/6.CombinedCUSPcasestudies.FINAL_.pdf.

- 6.Institute for Reproductive Health, Pathfinder International and Save the Children The GREAT Project, GREAT Results Brief; 2015. Available from http://irh.org/resource- library/brief-great-project-results/.

- 7.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1973–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, et al. Findings from the SASA! study: a cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of a community mobilization intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV risk in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0122-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2008;337:a506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diop NJ. The TOSTAN program: evaluation of community based education Program in Senegal. New York: Population Council; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, et al. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. Tampa (FL: ): University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamey GM. What are the barriers to scaling up health interventions in low and middle income countries? A qualitative study of academic leaders in implementation science. Global Health. 2012;8(11):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-8-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gay J, Croce-Galis M, Hardee K.. What works for women and girls: evidence for HIV/AIDS interventions. Washington DC: The Evidence Project, Population Council and What Works Association, Inc.; 2016; Available from: www.whatworksforwomen.org. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Remme M, Michaels-Igbokwe C, Watts C.. What works to prevent violence against women and girls? Evidence Review of Approaches to Scale up VAWG Programming and Assess Intervention Cost-effectiveness and Value for Money; 2014.

- 15.Michau L, Horn J, Bank A, et al. Prevention of violence against women and girls: lessons from practice. The Lancet. 2014;385(9978):1672–1684. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61797-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jewkes R, Flood M, Lang J.. From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: a conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1580–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61683-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander-Scott M, Bell E, Holden J.. DFID guidance note: shifting social norms to Tackle violence against women and girls (VAWG). London: VAWG Helpdesk; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Moreno C, Zimmerman C, Morris-Gehring A, et al. Addressing violence against women: a call to action. Lancet. 2015;385(9978):1685–1695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61830-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heilman B, Stich S.. Revising the script: taking community mobilization to scale for gender equality; 2016.

- 20.Hale F, Bell E, Banda A, et al. Keeping our core values ALIV[H] E. Holistic, community-led, participatory and rights-based approaches to addressing the links between violence against women and girls, and HIV. J Virus Erad. (2018);4(3):189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cislaghi B, Heise L.. Theory and practice of social norms interventions: eight common pitfalls. Global Health. 2018. DOI: 10.1186/s12992-018-0398-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cislaghi B, Heise L.. Using social norms theory for health promotion in low-income countries. Health Promot Int. 2018. day017 DOI: 10.1093/heapro/day017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mollen S, Rimal RN, Lapinski MK.. What is normative in health communication research on norms? A review and recommendations for future scholarship. Health Commun. 2010;25(6-7):544–547. DOI: 10.1080/10410236.2010.496704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catalytic Investments (2018). Available from: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/funding-model/funding-process-steps/catalytic-investments/.

- 25.World Bank World development report 2012: gender equality and development. Washington (DC): World Bank Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caprioli M, Boyer MA.. Gender, violence, and international crisis. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2001;45(4):503–518. doi: 10.1177/0022002701045004005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter, F., Ralph-Bowman, M., & Wallace, T. (Eds.). (2013). Aid, NGOs and the realities of women's lives: a perfect storm. Bourton-on-Dunsmore, Rugby: Practical Action Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellsberg M, Arango DJ, Morton M, et al. Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1555–1566. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durán LA. (2015). 20 Years of Shamefully Scarce Funding for Feminists and Women’s Rights Movements. AWID.

- 30.Moeller K. The gender effect: capitalism, feminism, and the Corporate politics of development. Oakland (CA): Univ of California Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strengthening Women’s Rights Organizations through International Assistance (2017). Match International and the Nobel Women’s Initiative. Available from: https://nobelwomensinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/REPORT-Strengthening-Women’s-Rights-Organizations-Through-International-Assistance-WEB.pdf.

- 32.ICWEA (2015). Are Women Organisations Accessing Funding for HIV & AIDS? Available from: ICWEA Website: http://www.icwea.org/download/2210/.

- 33.Moosa Z, Kinyili HM.. Big plans, small steps: learnings from three decades of mobilising resources for women's rights. IDS Bull. 2015;46(4):101–107. doi: 10.1111/1759-5436.12164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Htun M, Weldon SL.. The civic origins of progressive policy change: combating violence against women in global perspective, 1975–2005. Am Politic Sci Rev. 2012;106(3):548–569. doi: 10.1017/S0003055412000226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagaraj VK. ‘Beltway Bandits’ and ‘poverty Barons’: for-profit international development contracting and the military-development assemblage. Dev Change. 2015;46(4):585–617. doi: 10.1111/dech.12164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zakaria R. Canada's ‘Feminist’ Foreign Aid Is a Fraud; 2019, February 11. Available from: https://www.thenation.com/article/feminist-aid-canada-womens-economic-empowerment/.

- 37.Siegfried N, Narasimhan M, Kennedy CE, et al. Using GRADE as a framework to guide research on the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of women living with HIV–methodological opportunities and challenges. AIDS Care. 2017;29(9):1088–1093. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1317711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cislaghi B, Heise L.. Measuring gender-related social norms: report of a meeting, Baltimore Maryland, June 14–15, 2016. London: LSHTM; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costenbader E, Cislaghi B, Clark CJ, et al. Social norms measurement group commentary. SPECIAL ISSUE (forthcoming in Journal of Adolescent Health Special Supplement. March 2019).

- 40.Costenbader E, Lenzi R, Hershow RB, et al. Measurement of social norms affecting modern contraceptive use: A literature review. Stud Fam Plann. 2017;48(4):377–389. doi: 10.1111/sifp.12040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Auerbach JD, Parkhurst JO, Cáceres CF.. Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: conceptual and methodological considerations. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(sup3):S293–S309. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.594451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ackerly B, True J.. Reflexivity in practice: power and ethics in feminist research on international relations. Int Stud Rev. 2008;10(4):693–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2486.2008.00826.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collaborative Research as Structural Violence (2018, July 11). Available from: http://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2018/07/12/collaborative-research-as-structural-violence/.

- 44.Transactional sex and HIV risk: from analysis to action. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and STRIVE; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon G, with Welbourn A.. Guidelines for adapting the stepping stones and stepping stones plus training programme on gender, Generation, HIV, communication and relationship skills. London: Salamander Trust; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hickel J. The divide: a brief guide to global inequality and its solutions. New York: Random House; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patton MQ. Developmental evaluation: applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York (NY: ): Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doing Development Differently Manifesto (2014). Available from: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/events-documents/5149.pdf.