Abstract

Fetal “heartbeat” bills have become the anti-abortion legislative measure of choice in the US war on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). In 2019, Georgia House Bill 481 (HB 481) passed by a narrow margin banning abortions upon detection of embryonic cardiac activity, as early as six weeks gestation. The purpose of this study was to distinguish and characterise the arguments and tactics used by legislators and community members in support of Georgia’s early abortion ban. Our data included testimony and debate from House Health and Human Services and the Senate Science and Technology Committees; data were transcribed verbatim and coded in MAXQDA 18 using a constant comparison method. Major themes included: the use of the “heartbeat” as an indicator of life and therefore personhood; an attempt to create a new class of persons – fetuses in utero – entitled to legal protection; and arguments to expand state protections for fetuses as a matter of state sovereignty and rights. Arguments were furthered through appropriation by misrepresenting medical science and co-opting the legal successes of progressive movements. Our analysis provides an initial understanding of evolving early abortion ban strategy and its tactics for challenging established legal standards and precedent. As the battle over SRHR wages on, opponents of abortion bans should attempt to understand, deconstruct, and analyse anti-abortion messaging to effectively combat it. These data may inform their tactical strategies to advance sexual and reproductive health, rights, and justice both in the US context and beyond.

Keywords: abortion, anti-choice, pro-life, anti-abortion, legislation, policy, law

Résumé

Les lois dites du « battement de cœur » fœtal sont devenues la mesure législative anti-avortement de choix dans la guerre que les États-Unis d’Amérique livrent à la santé et aux droits sexuels et reproductifs. En 2019, l’État de Géorgie a adopté à une faible majorité la loi 481 (HB 481) qui interdit les avortements après la détection d’une activité cardiaque de l’embryon, dès six semaines de gestation. L’objet de cette étude était de distinguer et de caractériser les arguments et les tactiques que les législateurs et les membres de la communauté utilisent à l’appui de l’interdiction de l’avortement à un stade précoce en Géorgie. Nos données incluaient des témoignages et les débats de la Commission de la Chambre sur les services humains et de santé et de la Commission du Sénat sur les sciences et les technologies; les données ont été transcrites textuellement et codées en MAXQDA 18 à l’aide d’une méthode de comparaison constante. Les principaux thèmes comprenaient: l’utilisation du «battement de cœur» comme indicateur de la vie et donc du statut de personne; la tentative de création d’une nouvelle classe de personne – les fœtus in utero – ayant droit à une protection juridique; et les arguments pour élargir la protection de l’État aux fœtus en tant que question de souveraineté et de droits de l’État. Les arguments ont été étayés par l’appropriation en déformant la science médicale et en récupérant les succès juridiques des mouvements progressistes. Notre analyse permet une compréhension initiale de l’évolution de la stratégie d’interdiction de l’avortement à un stade précoce et ses tactiques pour remettre en question les normes et les précédents juridiques établis. Alors que la bataille fait rage sur la santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs, les opposants aux interdictions de l’avortement devraient tenter de comprendre, de déconstruire et d’analyser les messages anti-avortement pour les combattre efficacement. Ces données peuvent guider leurs stratégies tactiques afin de faire avancer la santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs, ainsi que la justice dans le contexte des États-Unis et au-delà.

Resumen

Los proyectos de ley relativos a los latidos cardíacos fetales han pasado a ser la medida legislativa antiaborto preferida en la guerra de EE. UU. contra la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos. En 2019, el Proyecto de Ley 481 de la Cámara de Representantes de Georgia (HB 481), aprobado por un estrecho margen, prohibió el aborto en casos en que se detecta actividad cardiaca embrionaria, tan temprano como a las seis semanas de gestación. El propósito de este estudio era distinguir y caracterizar las tácticas y los argumentos utilizados por legisladores y miembros comunitarios para apoyar la prohibición del aborto temprano en Georgia. Nuestros datos incluían testimonios y debates de los Comités de Salud y Servicios Humanos de la Cámara y de los Comités de Ciencias y Tecnología del Senado; los datos fueron transcritos palabra por palabra y codificados en MAXQDA 18 utilizando el método de comparación constante. Las principales temáticas eran: el uso de los “latidos cardíacos” como indicio de vida y, por ende, de condición de persona; el intento de crear una nueva clase de personas – fetos en útero – con derecho a protección jurídica; y argumentos para ampliar las protecciones estatales para fetos como cuestión de soberanía y derechos estatales. Los argumentos fueron promovidos por medio de apropiación distorsionando la ciencia médica y cooptando los logros legislativos de movimientos progresistas. Nuestro análisis ofrece una comprensión inicial de la estrategia en evolución relativa a la prohibición del aborto temprano y sus tácticas para cuestionar el precedente y las normas legislativas establecidas. A medida que continúa la batalla respecto a la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos, los oponentes a la prohibición del aborto deberían intentar entender, deconstruir y analizar los mensajes antiaborto para combatirlos de manera eficaz. Estos datos podrían informar sus estrategias tácticas para promover la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos, y la justicia, tanto en Estados Unidos como en el extranjero.

Introduction

Battles over sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) have been waged for decades across the globe. Where reproductive health researchers note the harms of unsafe abortion – and the safety of the medical procedure when performed by health professionals – anti-abortion advocates view it as murder.1,2 Where reproductive rights makes claim to the full range of sexual and reproductive health goods, facilities and services – including abortion – as part of the right to health, opponents view the “right to life” as paramount.2,3 Where Reproductive Justice combines reproductive health, rights and social justice in recognition of intersectional oppressions, anti-abortion advocates believe that some women use abortion out of convenience and that they should accept the responsibility of parenthood if they become pregnant.2,4 Abortion policy often flows from public discourse, with success oscillating from one side to the other.2 A successful civil society campaign led to the 2018 repeal of Ireland’s constitutional ban on abortion;5 yet the procedure is still banned in 26 countries, demonstrating global inconsistency.6 As people’s rights to access abortions and other sexual and reproductive health services advance, those opposed to the procedure respond by testing new tactics for restriction.

In the US, fetal “heartbeat” bills – crafted from “model legislation” – have increasingly become the anti-abortion legislative measure of choice since they were first introduced in 2011.7 Such legislation is designed to restrict women’s access to abortion after a “heartbeat” – or, more aptly, possible embryonic cardiac activity – is detectable.8 This notion is in contrast to the legal standards established by Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey.9,10 Abortion bans at earlier stages of gestation are part of a packaged legislative strategy by anti-abortion groups to erode existing abortion protections.11,12 These restrictions are likely to be challenged in US courts – and are ultimately intended to overturn Roe v. Wade in the US Supreme Court.

Because this paper is focused on anti-abortion rhetoric, and a direct report of the language used by anti-abortion proponents, we use “heartbeat” throughout. However, we emphasise that this is not our language. The presence of cardiac activity is not equivalent to the presence of a functioning heart or heartbeat, defined as the pulsation of the heart.13 The medical detection of cardiac activity may vary based on the methods used and the skill levels of providers.13 Nevertheless most “heartbeat” bills identify six weeks gestation, or four weeks post-fertilisation, as the time when cardiac activity is detected, restricting access to abortion after that gestational age.14 As a result, “heartbeat” bills function as near-total abortion bans; others refer to this type of legislation as early abortion or six-week abortion bans.15

Since 2011, almost 100 fetal “heartbeat” bills have been introduced in 25 states.8 In 2019, at least 16 states have proposed banning abortion at fetal “heartbeat.”8 To date, only three states have successfully enacted such proposed legislation; North Dakota and Arkansas enacted legislation in 2013, followed by Iowa in 2018. Each of these bills was struck down in either federal or state court, with the US Supreme Court refusing to hear them.16

Georgia House Bill 481 (HB 481): The Living Infants Fairness and Equality (LIFE) Act was initially sponsored by six members of the Georgia House of Representatives and introduced during the 2019 legislative session.17 HB 481 bans abortion upon the detection of a “heartbeat”; it also gives full legal rights and protections to “natural persons” in utero.17 HB 481 passed by a slim margin and was slated to come into force on 1 January 2020, effectively banning abortion across the state, and threatening the health of Georgian women of reproductive age (Figure 1). A legal challenge, Sistersong v. Kemp has been filed and a temporary injunction was granted in October 2019.18–20 As the battle over SRHR wages on, it is beneficial for reproductive health, rights, and justice advocates to understand, analyse, and deconstruct anti-abortion messaging in order to combat it. Public and legislative testimonies are under-utilised to understand anti-abortion policies with little empirical research systematically investigating the arguments, evidence and framing they employ.21 To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the legislative discourse surrounding fetal “heartbeat” bans. The purpose of this study was to distinguish and characterise the arguments and tactics used by legislators and community members in support of HB 481, Georgia’s early abortion ban.

Figure 1.

Georgia State Representative Ed Setzler, a sponsor of HB 481 receives a fist bump after passage of the bill. Photo credit: Bob Andres/AJC.com

Methods

Design and participants

HB 481 worked its way through the legislative process between its introduction on 25 February 2019 and 4 April 2019 when it was sent to the Governor for signature. Substantive discussions of the bill took place in March 2019 across House and Senate committee meetings – including community members and expert testimony – and legislative debates. We examined the publicly available video archives of these sessions using a qualitative narrative analysis approach. Qualitative methods are well suited for deep analysis into cultural norms, beliefs and experiences.22

The participants in the study consisted of the primary sponsor of HB 481 and 41 members of the Georgia legislature serving on either the House Health and Human Services Committee or the Senate Science and Technology Committee, as well as community members who testified in support of HB 481 during the public committee hearings.

Procedure

We utilised the publicly available legislative record to identify the committee meetings where public testimony and debate of the bill took place. The first author reviewed her calendar for dates in March 2019 during which she either attended or watched the live stream of HB 481 committee hearings. The same procedure was followed to identify the dates of both House and Senate floor debates and votes on the bill. These dates were compared to the publicly available calendar related to the bill. We identified 13 eligible sessions for examination. For the purposes of this paper, our data sources were limited to meetings of the House Health and Human Services Committee and the Senate Science and Technology Committee; during these sessions, community members gave testimony and members of the aforementioned committees engaged in a legislative debate of HB 481. We excluded the readings of the bill, and other non-substantive procedural discussions. All discussions of HB 481 from the relevant sessions we identified were converted from video format into audio files and transcribed verbatim using Happy Scribe, an automated audio-to-text transcription software; transcripts were checked for fidelity by a research assistant.

The second author developed an initial codebook based on her experience observing HB 481 related testimony and debate. The authors further fleshed out these codes based on their own experiences and knowledge of the subject. The second author and a research assistant added to the codebook based on their observations during the transcription fidelity checking process. Both authors and the research assistant met to discuss discrepancies and refine deductive code definitions. Abortion related deductive codes included terms frequently invoked by anti-abortion advocates such as abortion, life, and unborn child; other codes specific to early abortion ban legislation included “heartbeat” and personhood. The data were coded by the second author using MAXQDA 18 software (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany).23

We used a constant comparison approach, which combines a priori deductive coding and inductive thematic analysis.22 Descriptive memos were used to iteratively identify inductive codes and themes. Our analysis focused on arguments made by supporters of HB 481, namely community members, expert witnesses and legislators who were: the primary sponsor of the bill, and members of either the House Health and Human Services Committee, or the Senate Science and Technology Committee.

We created a word cloud of our codes to visualise the most frequently used codes; a word cloud is a visual display of text where the size in the display increases as a function of frequency. We then examined our MAXQDA codebook to determine the most frequently applied codes. We developed thick descriptions for parent codes with 25 or more coded segments excluding sub codes; we also developed thick descriptions for sub codes with 20 or more coded segments. Code saturation was reached for all codes with greater than 20 coded segments. Thick descriptions are a technique borrowed from ethnography where the researcher focuses on one code/theme and explicitly outlines findings or patterns.22 Codes with thick descriptions were: state (45 segments), heartbeat (42 segments), abortion (38 segments), life (35 segments), constitutional/federal (31 segments), protect (30 segments), health/medical (29 segments), unborn child (28 segments), census (26 segments), and personhood (21 segments). Codes with less than five segments were also noted as possible negative findings. These included, for example, disability (five segments), religion (four segments), and human rights/ethics (four segments).

Demographic information (race, gender and political affiliation) on legislators was gathered from the publicly available Georgia legislature webpage.24 It was not possible to glean similar demographic information from each community member.

Study ethics

Emory University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that the project was exempt from full review, as it did not meet the definition of “research” with human subjects as set forth in Emory policies and procedures, and federal rules. We do not believe we have introduced the potential for harm above and beyond what already exists by the nature of these data being publicly available.

Results

We found four major elements in the legislative discourse among supporters of HB 481. We describe each element and how they build upon one another. The major elements found in anti-abortion discourse included: the use of the “heartbeat” as an indicator of life and therefore personhood; an attempt to create a new class of persons – fetuses in utero – entitled to equal protection under the law; and the need to expand state protections for this class. All arguments were furthered by appropriating medical science and/or prior legal statutes or precedent.

Element 1. The “heartbeat” is an indicator of life and therefore personhood

HB 481’s sponsor and supporters asserted that detection of a “heartbeat” was a “legally significant and medically sound” indicator of (1) life, (2) “pregnancy viability,” and (3) distinct personhood.

“Heartbeat” was primarily coupled with the term “life,” seen as both the outcome of conception present with cardiac activity, and a “right of children in the womb.” In addition to using traditional anti-abortion “right to life” language, life within the legislative discourse was often established by its opposite – death as defined by the Determination of Death Act (DDA).25 Under this standard, death is the irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function, or the irreversible cessation of brain function. The lack of a heartbeat as a codified indicator of death was utilised by supporters of the bill who asserted that if death is the absence of a heartbeat, then its presence is a clear indicator of life. This thinking was described as “common sense.” Similarly, the term “flatline” was used to describe a common way of understanding the absence of life, and that therefore the presence of a “heartbeat” should be viewed as a sign of life. This view was challenged by a legislator who noted that the absence of both cardiac and respiratory function are required under the DDA – and under current DDA definitions cardiac activity alone would not constitute life. There was a marked absence of the use of religious language to connect “heartbeat” to life. Terms such as “God” and “religion” were used sparingly by both legislators and community members.

“Heartbeat” was also presented as an indicator of “pregnancy viability.” Participants noted that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) uses the detection of cardiac activity as a “key threshold” for fetal viability, but others noted that this is not the only threshold, nor was it “dispositive.” The information used to bolster this viability argument was inaccurate, and not present in the ACOG source referenced.26 One legislator (not a clinician) claimed a 95% chance of “pregnancy viability” upon the detection of cardiac activity, misconstruing medical facts and conflating fetal viability with non-viable pregnancy.26

Based upon this concept of “heartbeat” as an indicator of “pregnancy viability,” numerous dubious medical details about biological, anatomical and cardiovascular development were introduced. One legislator asserted:

“The cardiovascular system is the first organ system to reach a functional state. The heart begins to beat at three weeks and one day, two days post fertilization.”

Supporters of HB 481 consistently used the term “unborn child,” which served as a lexical bridge to link the concepts of “heartbeat” and personhood. Other similar terms were, “early infant in the womb,” “early infant,” “child in utero,” and “child” to attribute personhood to embryos and fetuses at “any or all stages of development.” By definition, the term embryo describes the period of development from conception to the six weeks gestation/eight weeks post-fertilisation and the term fetus from six weeks gestation/eight weeks post-fertilisation until birth.27 Therefore, the sponsor’s terms are inaccurate. Yet, the language deliberately mimics biological, human, and child development terminology in an attempt to add an air of medical credibility to the claim, which cannot be backed by scientific sources. One legislator stated:

“What I’m telling you when you think about a child … early infants is an infant that is in their early stages of development.”

The bill’s sponsor also attempted to biologically distinguish the embryo or fetus from the pregnant person, indicating the presence of other biological characteristics. For example, fetuses were described numerous times as having their own DNA and organ systems; some legislators pushed back noting that fetuses do not have fully developed organs or even unique fingerprints at six weeks gestation. The bill’s sponsor replied, “they’re developing [laughing/ loudness from the audience].”

In discussion of the bill several sceptical legislators called for accuracy and differentiated between fetal heart tones and a “heartbeat.” An amendment to change the language of the bill from “heartbeat” to a “functioning human heart” – a more accurate description of organ function – failed.

Element 2. As “living” beings, fetuses in utero are a class of persons entitled to protection under the law

Supporters of HB 481 argued that the presence of a “heartbeat” is a sign of life, and that life connotes personhood. Following this line of thinking supporters emphasised the value – and vulnerability – of fetuses, viewing them as a class of persons in need of legal protection. One legislator described his views:

“We recognize that no matter the manner of conception: whether a child’s conceived in a loving family, conceived in an unplanned way, conceived in rape, those children are all equally innocent before the law and of the same value.”

Fetal “vulnerability” or “innocence” was highlighted and reiterated numerous times by legislators throughout testimony and echoed by community supporters; fetuses were equated with vulnerable populations who experience oppression or those at risk of maltreatment. One supporter, a Christian pastor, argued:

“ … we must do more to protect the innocent, and the vulnerable, and the oppressed whether it is preventing the mistreatment of children who are disabled in medical situations, or of pregnant women who are in crisis, or innocent children in the womb. And I join my voice with theirs to call on you, our lawmakers, to stand together to do what’s right and to stand aside from partisan rhetoric to defend those who were innocent and those who were oppressed, to defend the sanctity of human life.”

After arguing the value of fetuses, supporters of HB 481 attempted to assert that fetuses in utero constitute a special class of persons in need of legal protection. In a telling interaction between legislators, the purpose of the bill was made abundantly clear:

Legislator 1: “My understanding is that really what you’re trying to do is to now recognize unborn children as natural persons in the state, which is something that has not been done previously under any statute and/or constitutional case law.”

Legislator 2: “I would agree with that. They said listen, if a state establishes personhood the entire Roe logic collapses … that is precisely the point, Senator, we’re putting a novel question before our courts and again in the line of the 14th Amendment we’re recognizing a right of an entire class of persons that’s not been recognized before HB 481 consistent with the paramount right.”

The 14th Amendment of the US Constitution28 – notable for the equal protection clause – was mentioned often and offered as the explicit constitutional basis of HB 481:

“The 14th Amendment, passed in 1868 to give full legal recognition to entire classes of persons that had never been given full legal recognition. That’s exactly what we’re doing here.”

When one legislator noted the language of “born or naturalized persons” in the 14th Amendment, the sponsor of HB 481 rebutted the argument citing the due process clause exclusively. The Bill’s sponsor linked the birth clause of the 14th Amendment exclusively to citizenship and the concept of personhood directly to equal protection, cherry-picking the clause for his ends.

Supporters of HB 481 asserted that just as the 14th Amendment was created to recognise the full humanity of Black Americans, it should be used now to acknowledge the “full humanity” of fetuses, going so far as to describe the need for protection of fetuses, as equivalent to that of other historic classes such as former slaves. Reference was made to the Three Fifths Compromise, whereby slaves’ lives had been valued as partial persons for tax and census purposes;29 an analogy between the Three Fifths Compromise and the language sometimes used to describe developing embryos as “groups of cells” was used in an attempt to demonstrate the perceived error in this thinking. Just as the 14th Amendment remedied the Three Fifths Compromise, proponents suggested that HB 481 would do the same for “unborn children.”

A community member in favour of the bill furthered this argument by noting three instances where classes of people were “stripped of their rights”: Dred Scott v. Sandford, Plessy v. Ferguson, and Roe v. Wade.9,30,31 The first two of these US Supreme Court cases were notably reversed by legislation and widely viewed in hindsight as erroneous rulings of the court. In concluding her remarks on this topic the community member noted:

“Georgia has a compelling interest to protect the most vulnerable among us, the same way this nation came back and protected Black people during slavery by passing the 13th and 14th Amendment, and by protecting Dred Scott and others with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This is no different in my mind.”

Element 3. States are entitled to legislate on the expansion of fetal rights as a matter of state’s rights

Having attempted to establish the “unborn” as a class of persons in need of special protections, proponents of HB 481 argued for more expansive legal statutes at the state level in an attempt to create a “national standard” above and beyond federal protections. This argument was grounded in the notion of state’s rights and sovereignty, citing the Georgia Constitution and federal case law. Concerns about the fiscal and social implications of the legislation plagued this part of the argument.

Specific reference was made to the 4th Amendment of the Georgia Constitution. This section of law relates to privacy; supporters of HB 481 argued that Georgia provides greater protection than at the federal level by, for example, limiting DNA testing upon arrest to felony charges. Proponents argued that HB 481 serves to expand fetal rights beyond federal protections. Several US Supreme Court cases were noted in making the case for states expansion of rights including, Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins and Robbins v. California.32,33 One legislator noted that unlike HB 481, the Pruneyard case was linked to direct expansion of the state constitution while HB 481 is not.

An attorney and supporter of the bill alluded to federalism and the need for states to reassert their rights and sovereignty in this arena. She stated:

“By passing this bill Georgia can join multiple other states that are reclaiming their constitutional autonomy in this area … so I urge you to let Georgia join the other states that have made a bold move to say that under the Constitution this is our role … It is not yours [the federal government] … Justice Roberts said once that the states need to start acting like the sovereign entities that they are. And I think this is a great opportunity to do that.”

The legal argument was laid out quite plainly by this community supporter. She summarised the major arguments in favour of the Constitutionality of the legislation as:

the State’s substantial – and according to the 8th circuit “profound”34 – interest in protecting life;

that legislative, not court action should decide how to protect unborn “life” based on the emergence of new medical knowledge and technologies since past legal precedent; and

a Federalist argument that states must rebalance sovereignty and state’s rights.

In addition to US Supreme Court Chief Justice Roberts, specific references to past and current national Republican leaders – President Abraham Lincoln, President Ronald Reagan and President Donald J. Trump – were also made in this context.

Both supporters and detractors of HB 481 raised numerous concerns about the sweeping effect of the bill on the Georgia code and economic functioning. These concerns included implications for state census counts, child support provision, enrolment of fetuses in Medicaid, and the operationalisation of the Sponsor’s claim that fetuses could be claimed as dependents for state tax deductions. In discussion of the cost of such changes to the code, the Bill’s sponsor estimated tax deductions resulting from the legislation to be between $7 and $9 million. Another legislator from the same political party countered stating:

“There is not a fiscal note. And, in addition to notification provisions, this is for a tax deduction. We have no idea how much this tax deduction is going to cost. There will also be criminal enforcement costs that are going to go with that. We have no idea how much that’s going to cost. And there’ll be two tiers of constitutional challenges with this. First, the challenge under the current U.S. Supreme Court law. But secondly, this bill provides standing for individuals to continually sue the state of Georgia over the provisions in this bill. So we’re going to have massive cost.”

Concerns about the criminal prosecution of medical professionals, pregnant women and health care organisations were raised in bill discussion. Exceptions in cases of rape, incest and medical emergency were also added to the bill in response to similar concerns. The introduction of a refined definition of medical futility was framed by the bill’s sponsor as consensus building:

“there is a provision for if a physician determines that a pregnancy is medically futile … that abortion as it’s allowable under the current law would be allowable. It defines medical futility in this. Again, I’ve got some misgivings about this but again Madam Chair in the interest of providing a bill that we can move towards consensus.”

Several legislators remained troubled by the requirement for a police report in cases of rape or incest in order to actualise these exceptions, especially given known delays in reporting among survivors of such violence. Few suggestions for operationalising the bill in light of these concerns were presented by supporters of HB 481.

Element 4. Credibility is established through the appropriation of medical science and law

Throughout the legislative process supporters of HB 481 appropriated medical science and law to bolster their arguments; fields as diverse as obstetrics and gynaecology, child development, international human rights norms, and federal civil rights statutes were all used (see Table 1). Supporters of HB 481 used tactics such as misinformation, the misrepresentation of facts, co-optation and lip service to lend credibility to their position. An anti-abortion playbook available online underscores that this strategy and these tactics are deliberate.35

Table 1. Appropriation and tactics used in HB 481 legislative debate.

| Appropriation of | Tactic used | Anti-abortion example | Fact checking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical science – obstetrics and gynaecology | Misinformation | “The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recognizes in their 2015 guidelines, that the standard for a viable intrauterine gestation as it’s called is heartbeat that you know a pregnancy is viable at that point. And at that point you have a 95 percent likelihood of the pregnancy going forward to birth.” |

|

| Medical science – obstetrics and gynaecology | Misrepresentation of facts | “I do want to highlight that the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recognizes there’s one threshold for the standard of a viable pregnancy. There are some others but the key threshold is the presence of a heartbeat. You have a viable pregnancy when a heartbeat is present.” |

|

| Medical science – paediatrics and stages of child development | Misrepresentation of facts | “I think it’s important to understand, you know we’re talking about infants … We simply use the word early infant as a is a sort of a general term to talk about what we recognize the child in the womb … But they’re early in their development.” |

|

| Law – state civil rights | Co-optation | “If you think back to the same sex marriage debate, the state of Massachusetts recognized the franchise of marriage more expansively in Massachusetts than the minimum requirement of federal law and the federal laws … This is walking that same tradition.” |

|

| Law – federal civil rights | Co-optation | “Georgia has a compelling interest to protect the most vulnerable among us, the same way this nation came back and protected Black people during slavery by passing the 13th and 14th Amendment, and by protecting Dred Scott and others with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This is no different in my mind.” |

|

| Law – international human rights | Lip service | “Ellen Willis is putting women back into the abortion debate from 2005 is an argument that supports women’s rights and feminism in terms of allowing all abortions to occur. She discusses abortion with the perspective that women’s rights are the issue not human life … Banning abortion is not a way of forgetting about the significance of a woman’s life.” |

|

Credible scientific sources such as the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) were often misrepresented; reference to ACOG was sometimes coupled with falsehoods or otherwise inaccurate information. Supporters of HB 481 confounded existing medical science with their own new terminology such as “pregnancy viability” and “early infant” – vocabulary not defined or used within the field of medicine. For example, the term “pregnancy viability” does not appear in ACOG guidelines nor is it defined, while the term non-viable pregnancy does exist in the medical literature26; the terms “unborn child” and “early infant” are not in keeping with obstetric standards describing fetal development.36

The use of legal norms and precedent primarily took the form of co-optation, and occasionally lip service. Supporters of HB 481 claimed the struggles of Black and LGBTQIA Americans as akin to their own. Both sets of claims were grounded in norms of non-discrimination under either State or Federal constitutional law. These instances of co-optation drew upon victories led by progressive movements – namely the US civil rights and gay rights movements. The case of Goodrich v. Department of Public Health37 was used for this purpose, as well as being offered as an example of states’ rights expansion. Human rights law was used in a superficial manner without a clear substantive connection to existing norms and standards.

Discussion

The public testimony and legislative debate surrounding HB 481 revealed important elements of anti-abortion approaches in the US battle around abortion, including the what and how of early abortion ban strategy. There are three prongs to the latest approach: using the “heartbeat” as an indication of life, creating a new protected class of persons with subsequent legal protections, and the expansion of states’ rights to guarantee legal protections to fetuses above and beyond those afforded by federal law. Drawing principally on sources from medical science and law, the primary tactic for advancing this strategy was one of appropriation using misinformation, misrepresentation, co-optation and lip service. These legislative strategies are deliberate and largely copied from “model legislation” and anti-abortion talking points.8,11,12

What the new anti-abortion strategy aims to do

Legislators supporting HB 481 sought to use the presence of possible cardiac activity, typically detectable around six weeks of gestation, as a marker of life. This benchmark is considerably earlier than well-established medical standards for fetal viability,34 an important concept within existing legal precedent.9,10 The establishment of the “heartbeat” as an indicator of life and therefore personhood was a critical piece of the HB 481 argumentation. Supporters of HB 481 used simplified non-scientific understandings of the meaning of a “heartbeat” and “pregnancy viability” to personify the human nature of fetuses. The “heartbeat” was also used to distinguish the fetus as an individual distinct from the pregnant person, negating the dependence of the fetus on the mother during gestation. While some legislators pushed back against the oversimplification of the DDA and erroneous assertions about the development of fetal organ systems, those in favour of the legislation were not sufficiently troubled by inconsistencies to deter them from supporting the new “heartbeat” threshold.

HB 481, along with other early abortion bans, attempts to create a new protected class of persons under US Constitutional law. Principally drawing upon the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution, supporters of HB 481 argued that fetuses are persons entitled to legal protection; this personhood argument has broad implications for reproductive health and rights beyond abortion.44 Parallels were drawn between the former slave Dred Scott who was notably denied his claim to constitutional protections before the existence of the 14th Amendment. Subsequently, groups including Black Americans and same-sex couples have successfully made claims towards the furtherance of their civil rights under the 14th Amendment. For example, in the case of Brown v. Board of Education,45 racial segregation was ruled unconstitutional on the basis of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment; similarly, the US Supreme Court case of Obergefell v. Hodges39 found protections for same-sex marriage under both the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment. Supporters of HB 481 drew parallels between these groups’ claims and their claims on behalf of “unborn children,” foreshadowing their legal strategy for a future claim before the US Supreme Court. Some have pointed to the convenience of advocating for “voiceless” fetuses while abandoning the vulnerabilities of other poor and marginalised groups.46 Comparing the “heartbeats” of fetuses to historical and current efforts against white supremacy and homophobia demeans the lived experience of those facing such systemic oppressions.

The final element of the new anti-abortion strategy was the attempt to expand state sovereignty in an effort to protect fetal rights. This approach provides two possible pathways for success: one via state legislative restrictions on abortion and the other a judicial pathway towards an increasingly conservative US Supreme Court. This piece of the strategy attempts to reset the balance of power between the federal courts and state legislatures. On one hand, supporters claim that state legislatures are entitled – and perhaps obligated – to expand rights to protected classes of persons above and beyond the protections of federal law. This portion of logic is designed to place power in the hands of state legislative authorities and is supported by a roadmap for doing so.47

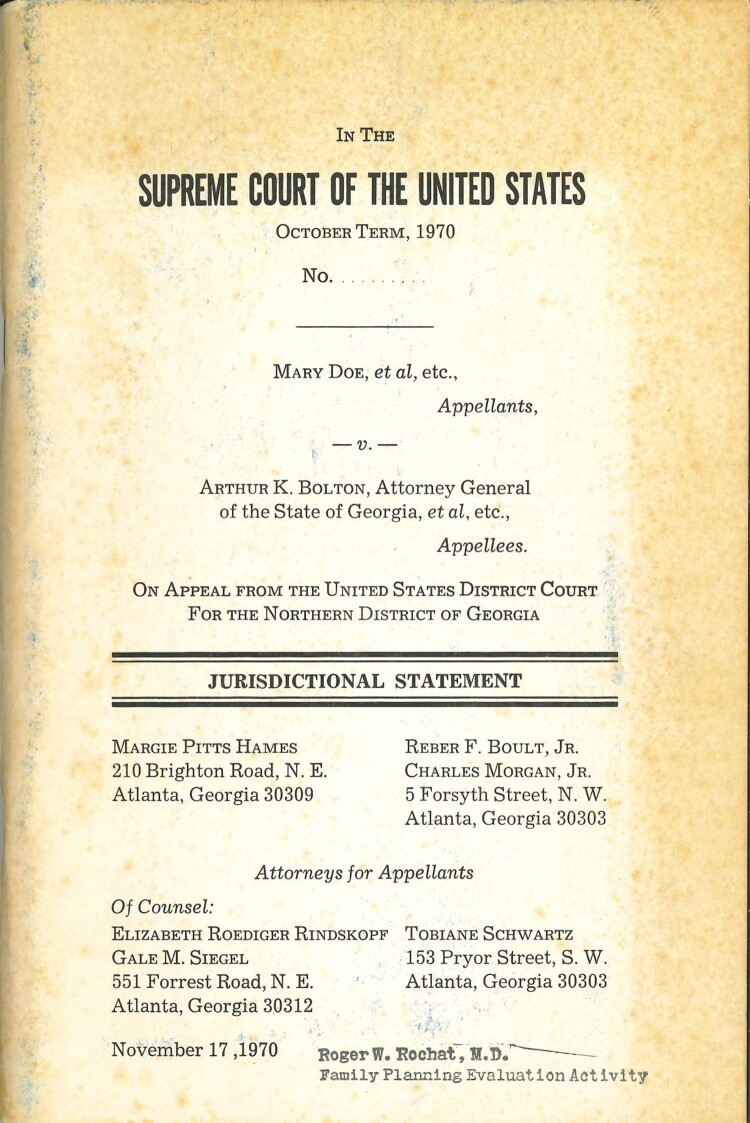

Strict abortion restrictions have become extremely popular in Republican-controlled state legislatures, especially since the appointment of US Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh in 2018.8 Proponents of HB 481 were likely aware that the law would be challenged in court and so are prepared to advance a states’ rights argument in the event that the US Supreme Court agrees to hear a case related to the legislation. It is worth noting that the US Supreme Court case of Doe v. Bolton originated in Georgia.48 Though lesser known than Roe v. Wade it was equally important in ensuring abortion as a constitutional right and overturning existing abortion law in Georgia.9,48 Time will tell if HB 481 will face the same fate as previous Georgia statutes restricting abortion (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Jurisdictional statement in the US Supreme Court case of Doe V. Bolton. Photo credit: Dabney P. Evans; materials courtesy of Roger W. Rochat, MD whose scientific work on deaths in Georgia as a result of illegal abortion was cited in the case

In 2019, Kentucky, Mississippi, Ohio, and Georgia all passed and signed fetal “heartbeat” bills into law.8 This dramatic increase in the passage of fetal “heartbeat” legislation indicates that anti-abortion proponents may believe that the time is right to mount a direct challenge to Roe v. Wade, and that this argument is the one to make. The composition of the Supreme Court and the current political climate has left Roe v. Wade more vulnerable than it has ever been, and anti-abortion proponents do not intend to waste their opportunity.

How legislators and anti-abortion advocates are advancing their strategy

Appropriation was the primary tactic by which supporters of HB 481 advanced their cause. They did so mostly by misrepresenting medical science and co-opting the legal successes of progressive movements. With regards to medical science, anti-abortion legislators and community members oversimplified complex concepts and directly appropriated language relating to viability, defining death, and child development. They reduced complicated scientific processes, medical experiences and decisions into extremely simple terms. Use of “heartbeat” was deliberate evoking popular knowledge, for example, hearing fetal heart tones using a Doppler ultrasound; advances in sonography were also used to advocate for increased ability to see and hear the presence of “life” during a pregnancy. The repeated use of the phrase “common sense” served to connect these ideas to lay audiences without medical or biological training. Furthermore, discussing only the “heartbeat” served to obscure the complex development of the cardiovascular system and ultimately the heart organ, purporting an almost homunculus view of fetal cardiac development. This false equivalency served the purpose of connecting the detection of blood flowing through cardiac cells to the concept of life and personhood. These arguments were a direct response to increased calls for evidence-based legislation. However, the evidence brought up during legislative testimony was replete with logical fallacies and factual inaccuracies. The use – or in this case, misuse – of science is a deliberate tactic;35 the absence of religious argumentation that we observed in our data is a complementary method.

Reproductive health advocates have long framed abortion as a women’s rights issue, and scientific data about the safety of abortion and harms of unsafe abortion are often touted as part of women’s health concerns. In the recent past, anti-abortion advocates have responded by co-opting the language of women’s health and science, focusing most recently on women’s health protection.49 Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP) laws serve as an example. While not abandoning this explanatory position, current anti-abortion efforts like HB 481 appear to be layering on a protectionist argument for unborn persons.50 This approach is grounded in gender paternalism; it also creates a false equivalency between the rights of women and the “rights” of the unborn.51 Despite the prior ruling of Roe v. Wade that the unborn do not have rights, legislators are now making the argument that they do by cherry-picking the 14th Amendment. They ignore portions of the Constitution that do not fit their argument, focusing on aspects of the law that suit their aims. Recognising that it is not uncommon for rights to be in tension, anti-abortion supporters further their equivalency by proposing a balancing test pitting women’s rights against fetal rights. However, it is clear that patriarchal control of women’s bodies and the furtherance of fetal rights is the true goal, since women’s health was mentioned sparingly and only in reference to prompting by legislators opposed to HB 481.

Widespread knowledge of human rights language makes it accessible to lay audiences. However, without a substantive connection to human rights legal norms and standards its use in the context of HB 481 served little value other than laying claim to rights. This lip service or use of buzzwords adds little beyond the perceived value (positive or negative) of the terms themselves. In fact, while human rights frameworks do not comment on when life begins they are clear that access to abortion and post-abortion care is part and parcel of the right to health.3 Human rights bodies frequently make recommendations to countries where abortion is banned noting the harms of such policies to women’s health and rights.52

Proponents of HB 481 further set out to capitalise on the gains of progressive groups from within civil society who have successfully advocated for the rights of vulnerable groups such as racial and ethnic, and sexual and gender minorities. The discrimination and challenges facing Black Americans and LGBTQIA people were co-opted in making discrimination claims on behalf of the “unborn.” In yet another false equivalency such claims compared past views of slaves, Black Americans and LGBTQIA persons as comparable to current views of fetuses, devaluing the lived experiences of these groups who suffered – and continue to suffer – from structural racism and homophobia, and minimising the real and measurable harm from past and ongoing discrimination against them. The hypocrisy in these forms of appropriation seems ludicrous given that few if any anti-abortion activists are also known to be advocating in anti-racist, gay pride, right to health, or other intersectional social justice spaces.

However, these outrageous claims served a purpose – building a clear case to challenge Roe v. Wade. Surprisingly, the current strategy appears to take a positivist law approach where lawmakers are asked to consider tenets of Roe v. Wade in the contemporary context and time that has passed since prior precedent. They propose striking down tenets of Roe v. Wade based on advances in our moral understanding of abortion, and in ultrasound technology. They argue that because newer, more sensitive technology can detect the “heartbeat” at earlier stages of pregnancy, the standards for our understandings of viability should change. This same strategy was successfully employed in the case of Gonzales v. Carhart, which upheld the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act.34 It may also be employed in the forthcoming case of June Medical Services LLC v. Gee where the US Supreme Court has agreed to revisit TRAP laws.

Adding to the strategy of Gonzales v. Carhart, legislators urged that the creation of a new class of persons is needed because our moral frameworks have evolved over time. They used the example of the legalisation of same-sex marriage as an advancement in social understanding around the need for increased rights of vulnerable groups. This positivist stance is in direct opposition to the originalist perspective usually espoused by conservative justices who believe that because the framers of the Constitution did not permit abortion, the issue is settled.53 The positivist approach may be a point of tension within conservative legal circles and of interest to those interested in exposing inconsistencies in the legal argumentation.

Fiscal concerns, including potential health and legal costs, seemed to be the bill’s biggest stumbling block – even among supporters of the legislation. Georgia’s decision not to expand Medicaid – and the state’s ability to provide care to low-income pregnant people in the face of an increased number of births was one concern; given that Georgia is facing cuts to the state budget, impacting child welfare, questions remain about other true costs of what some have called a forced birth bill. Independent economic analyses of fetal “heartbeat” legislation could be a useful tool for those opposed to it. Legislators were also uneasy about the implementation of HB 481 and resulting legal challenges taken against the state and numerous constituent groups including pregnant people and medical professionals who serve them. These concerns were never adequately addressed by the bill’s sponsors.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the study. Because the data came from the public record, we did not have the ability to probe; however, both authors were familiar with the local media coverage and public discourse related to the legislation and as residents of Georgia we believe we have an accurate understanding of the context.

Because we did not directly collect the data from participants, we were unable to ask legislators and community members specific demographic information including their age, race, gender, political affiliation and position on HB 481. We were able to gather political affiliation for legislators and ascribed race and gender by examining their profile photos on the Georgia legislature webpage. Based on our observations, among the 41 committee members, legislators were predominantly White (n = 29), male (n = 26) and Republican (n = 25).

While we had video of community members, we did not have time to systematically collect data on race and gender and align those data with the audio transcripts. As a result, we were unable to report quantitative information on the demographics of community members, though we share our anecdotal observations of their perceived race and gender in aggregate as largely White and female. Community members were sometimes asked about their residence and we noted this information where possible including that a number of those who testified publicly were from outside of Georgia. Future research should carefully ascribe race, gender, and party affiliation to individuals providing testimony as part of a holistic analysis of rhetorical strategy.

In coding the data, we had to discern the participants’ position on HB 481 based on their statements. In doing so, it is possible that we may have miscategorised some respondents’ views. In addition, some nuance and detail may be missing from our analysis because of our focus on overarching arguments and strategies used during the discourse. Finally, viewpoints and voices of those who did not support the bill are under-represented in this analysis because of the focus on supporters of HB 481.

Our analysis is the first of its kind examining early abortion ban legislative discourse in a systematic way; it provides an initial understanding of evolving early abortion strategy and its tactics. Our future work will examine the rhetoric of those opposing early abortion legislation, and the ways in which the rhetoric of those supporting and opposing early abortion bans intersect or disconnect. For example, both sides use similar terms like health but often have different meanings for the same language. How do these semantic differences enter into legislative debate and influence law making? Similarly, future research might explore which messages most influence lawmakers when engaged in abortion policy-making. Finally, given that early abortion bans are sweeping across many states, a multi-state comparison examining the discourse across states would provide further insight into the grand strategy of anti-abortion advocates.

Conclusions

The war on SRHR is happening on both global and domestic battlefields. Anti-abortion activists have taken lessons from the Global Gag Rule and applied them in the domestic context through new Title X Family Planning restrictions.54 Similarly, early abortion ban legislation in the US is testing the legislative and judicial branches of governments; it is also evolving quickly, as evidenced by recent legislation introduced in South Carolina where an entire section of the bill makes declaratory statements about medical research.55 Such legislation is likely to be replicated in global contexts, especially if viewed as a successful strategy for challenging existing abortion precedent.

HB 481 passed by a close margin and is currently under challenge in federal court18 (Figure 3). The law was slated to enter effect on 1 January 2020; however, a temporary injunction to forestall the law is now in place as the case makes its way through the courts.20 The Georgia law is part of a wave of early abortion bans sweeping across the US and there are a number of important lessons to be learned from analysis of the lawmaking process.

Figure 3.

Supporters watch Georgia Governor Brian Kemp sign HB 481 into law on 7 May 2019. Photo credit: Bob Andres/AJC.com

Our analysis describes that in the wave of early abortion ban legislation new argumentation and tactics are being used to challenge well-established legal standards, ideally culminating in a challenge to existing abortion precedent. We shed light on decades of legal and social movement tactics which are now being deployed in specific ways.56 These bans are part of a greater constellation of restrictions on reproductive health access. As the battles over SRHR wage on, advocates for reproductive health, rights and justice must understand, analyse, and deconstruct anti-abortion messaging in order to effectively combat it. Advocates may use these data to inform their own tactical strategies to advance sexual and reproductive health, rights, and justice both in the US context and beyond.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Shanaika Grandoit for her assistance with transcription and coding and to Roger Rochat, Lisa Haddad and Stu Marvel for their review of the manuscript in advance of submission. We also express our gratitude to Kelli Stidham Hall and our colleagues at RISE for their support of this work. Finally, we wish to acknowledge the community members and legislators who publicly debated this bill as part of a participatory democratic process. DPE was responsible for the study design, analysis and manuscript development. SN was responsible for codebook development, data coding and analysis and contributed to manuscript development.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by an anonymous donor through the Emory University Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast (RISE) and a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund (SFPRF). The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of RISE or SFPRF.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the authors. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: Living Infants Fairness and Equality (LIFE) Act; 6 March 2019: House HHS committee hearing; 14 March 2019: Senate Science and Technology Committee; 7 March 2019: House floor; 22 March 2019: Senate Chamber; 18 March 2019: Senate Science and Technology Committee.

ORCID

Dabney P. Evans http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2201-5655

Subasri Narasimhan http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6494-1497

References

- 1.Luffy SM, Evans DP, Rochat RW.. “Regardless, you are not the first woman”: an illustrative case study of contextual risk factors impacting sexual and reproductive health and rights in Nicaragua. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0771-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ProCon.org . Should abortion be legal?; 2019. Available from: https://abortion.procon.org/

- 3.CESCR . General comment no. 22: the right to sexual and reproductive health. New York: United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; 2016. (UN Doc E/C.12/GC/22). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross L, Solinger R.. Reproductive justice: an introduction (reproductive justice: a new VISION for the 21st century). Oakland: University of California Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Together for Yes . The national campaign to remove the eighth amendment; n.d. Available from https://www.togetherforyes.ie/

- 6.Center for Reproductive Rights . The world’s abortion laws map; n.d. Available from https://reproductiverights.org/worldabortionlaws

- 7.Faith2Action . Model heartbeat [example]; n.d. Bill example: http://f2a.org/images/Model_Heartbeat_Bill_Apr_2019_version.pdf. Available from http://www.f2a.org/

- 8.Heartbeat Bans . Legislative tracker: heartbeat bans. Rewire.News. 2019. Available from https://rewire.news/legislative-tracker/law-topic/heartbeat-bans/

- 9. Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). [PubMed]

- 10. Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

- 11.Americans United for Life . Legislation; n.d. Available from https://aul.org/what-we-do/legislation/

- 12.Ryman A, Wynn M. For anti-abortion activists, success of “heartbeat bills” was 10 years in the making. USA Today. 2019. Available from https://publicintegrity.org/state-politics/copy-paste-legislate/for-anti-abortion-activists-success-of-heartbeat-bills-was-10-years-in-the-making/

- 13.American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . ACOG opposes fetal heartbeat legislation restricting women’s legal right to abortion [position statement]; 2017. Available from https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2017/ACOG-Opposes-Fetal-Heartbeat-Legislation-Restricting-Womens-Legal-Right-to-Abortion?IsMobileSet=false

- 14.North A, Kim C. The “heartbeat” bills that could ban almost all abortions, explained. Vox. 2019. Available from https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/4/19/18412384/abortion-heartbeat-bill-georgia-louisiana-ohio-2019.

- 15.Harmon A. “Fetal heartbeat” vs. “forced pregnancy”: the language wars of the abortion debate. The New York Times. 2019. Available from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/us/fetal-heartbeat-forced-pregnancy.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_190523.

- 16.Ravitz J. Courts say anti-abortion “heartbeat bills” are unconstitutional. So why do they keep coming? CNN. 2019. Available from https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/26/health/heartbeat-bills-abortion-bans-history/index.html.

- 17.HB 481 Living Infants Fairness and Equality (LIFE) Act, H.B. 481, O.C.G.A. 5.6.34 ; 2019. Available from http://www.legis.ga.gov/Legislation/en-US/display/20192020/HB/481

- 18.American Civil Liberties Union. Sistersong v. Kemp ; 2019. Available from https://www.aclu.org/legal-document/sistersong-v-kemp-filed-complaint

- 19.American Civil Liberties Union. Motion Sistersong v. Kemp . Available from https://www.aclu.org/legal-document/brief-support-motion-preliminary-injunction

- 20.Prabhu MT. Federal judge blocks Georgia anti-abortion law. Atlanta Journal Constitution. 2019. Available from: https://www.ajc.com/news/state-regional-govt-politics/federal-judge-blocks-georgia-anti-abortion-law/yh1ttzbYdTcqiUT7OkyqkO/

- 21.Druckman J. On the limits of framing effects: who can frame? J Politics. 2003;63(4):1041–1066. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hennink M, Hutter I, Bailey A.. Qualitative research methods. London: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.MaxQDA . Software for qualitative data analysis. Version 18.2. Berlin: VERBI Software – Consult – Sozialforschung GmbH; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Georgia General Assembly ; n.d.. Available from http://www.legis.ga.gov/en-US/default.aspx

- 25.Georgia Code, O.C.G.A. 31-10-16 ; 2010. Available from https://law.justia.com/codes/georgia/2010/title-31/chapter-10/31-10-16/

- 26.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Early pregnancy loss. ACOG practice bulletin no. 200. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;132(5):e197–e207. Available from https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Bulletins/Committee-on-Practice-Bulletins-Gynecology/Early-Pregnancy-Loss?IsMobileSet=false [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Barfield WD. Standard terminology for fetal, infant, and perinatal deaths [clinical report]. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e2016055. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. U.S. Const. Amend. XIV.

- 29.Madison J. The writings of James Madison, comprising his public papers and his private correspondence, including his numerous letters and documents now for the first time printed. Hunt G, editor. New York (NY: ): Putnam’s; 1900. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857).

- 31. Plessy v. Ferguson, 63 U.S. 537 (1896).

- 32. Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins, 447 U.S. 74 (1980).

- 33. Robbins v. California, 453 U.S. 420 (1981).

- 34. Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007).

- 35.Ruze C, Schwarzwalder R.. Best pro-life arguments for secular audiences. Family Research Council; n.d.. Available from https://www.frc.org/brochure/the-best-pro-life-arguments-for-secular-audiences [Google Scholar]

- 36.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Periviable birth. Obstetric care consensus no. 6. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e187–e199. Available from https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Obstetric-Care-Consensus-Series/Periviable-Birth?IsMobileSet=false [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37. Goodrich v. Department of Public Health, 440 Mass. 309 (2003).

- 38.Achiron R, Tadmor O, Mashiach S.. Heart rate as a predictor of first-trimester spontaneous abortion after ultrasound-proven viability. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(3 Pt 1):330–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. (2015).

- 40. U.S. Const. Amend. XIII.

- 41. Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88–352, 78 Stat. 241 (1964).

- 42. Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. 89–110, 79 Stat. 437 (1965).

- 43. CCPR. General comment no. 36: the right to life. New York: United Nations Committee on Civil and Political Rights; 2018. (CCPR/C/GC/36).

- 44.Will JF. Beyond abortion: why the personhood movement implicates reproductive choice. Am J Law Med. 2013;39:573–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

- 46.Martinchek L. The convenience of advocating for “the unborn”. Medium. 2019. Available from https://medium.com/@xLauren_Mx/the-convenience-of-advocating-for-the-unborn-4a7e0ec68385.

- 47.Dunaway RM. Personhood strategy: a state’s Prerogative to take back abortion law. Willamette L Rev. 2010;47:327. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973). [PubMed]

- 49. Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. (2016).

- 50.Siegel RB. The new politics of abortion: an quality analysis of woman-protective abortion restrictions. U. Ill. L. Rev. 2007: 991. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siegel RB. Dignity and the politics of protection: abortion restrictions under Casey/Carhart. Yale L J. 2007;117:1694. doi: 10.2307/20454694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bueno de Mesquita J, Fuchs C, Evans DP.. The future of human rights accountability for global health through the universal periodic review. In: Gostin L, Meier BM, editors. Human rights in global health: rights-based governance for a globalizing world. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cassidy R. Scalia on abortion: originalism … but why? Touro L. Rev. 2016;32:741. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carter D. Trump’s “devastating and awful” title X restrictions go into effect. Rewire.News. 2019. Available from https://rewire.news/article/2019/07/16/trumps-devastating-and-unlawful-title-x-restrictions-go-into-effect/

- 55.SC Fetal Heartbeat Protection from Abortion Act, H. 3020, O.C.S.C .; 2019. Available from: https://www.scstatehouse.gov/sess123_2019-2020/bills/3020.htm

- 56.Rolingher D. Abortion politics, mass media, and social movements in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the authors. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: Living Infants Fairness and Equality (LIFE) Act; 6 March 2019: House HHS committee hearing; 14 March 2019: Senate Science and Technology Committee; 7 March 2019: House floor; 22 March 2019: Senate Chamber; 18 March 2019: Senate Science and Technology Committee.