Abstract

Unwanted pregnancy and unsafe abortion contribute significantly to the burden of maternal suffering, ill health and death in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This qualitative study examines the vulnerabilities of women and girls regarding unwanted pregnancy and abortion, to better understand their health-seeking behaviour and to identify barriers that hinder them from accessing care. Data were collected in three different areas in eastern DRC, using in-depth individual interviews, group interviews and focus group discussions. Respondents were purposively sampled. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions were screened for relevant information, manually coded and analysed using qualitative content analysis. Perceptions and attitudes towards unwanted pregnancy and abortion varied across the three study areas. In North Kivu, interviews predominantly reflected the view that abortions are morally reprehensible, which contrasts the widespread practice of abortion. In Ituri many perceive abortions as an appropriate solution for reducing maternal mortality. Legal constraints were cited as a barrier for health professionals to providing adequate medical care. In South Kivu, the general view was one of opposition to abortion, with some tolerance towards breastfeeding women. The main reasons women have abortions are related to stigma and shame, socio-demographics and finances, transactional sex and rape. Contrary to the prevailing critical narrative on abortion, this study highlights a significant need for safe abortion care services. The proverb “Better dead than being mocked” shows that women and girls prefer to risk dying through unsafe abortion, rather than staying pregnant and facing stigma for an unwanted pregnancy.

Keywords: termination of pregnancy, induced abortion, access to safe abortion, medical abortion, stigma, healthcare provider’s attitude, Democratic Republic of Congo, Médecins Sans Frontières

Résumé

Les grossesses non désirées et les avortements à risque contribuent sensiblement à la charge de souffrance, de morbidité et de mortalité maternelles dans la République démocratique du Congo (RDC). Cette étude qualitative examine les vulnérabilités des femmes et des jeunes filles concernant la grossesse non désirée et l’avortement, pour mieux comprendre leur comportement de recherche de soins et identifier les obstacles qui les empêchent d’avoir accès aux services de santé. Les données ont été recueillies dans trois régions de la RDC orientale, au moyen d’entretiens individuels approfondis, d’entretiens de groupe et de discussions par groupe cible. Les répondants ont été sélectionnés par échantillonnage dirigé. Tous les entretiens ont fait l’objet d’un enregistrement audio et ont été transcrits textuellement. Les transcriptions ont été triées pour en tirer des informations pertinentes, codées manuellement et examinées en utilisant une analyse qualitative du contenu. Les perceptions et les attitudes à l’égard de la grossesse non désirée et de l’avortement variaient entre les trois régions de l’étude. Au Nord-Kivu, les entretiens reflétaient de manière prédominante l’idée que l’avortement est moralement répréhensible, ce qui contraste avec la pratique fréquente des interruptions de grossesse. À Ituri, beaucoup jugeaient l’avortement comme une solution adaptée pour réduire la mortalité maternelle. Les contraintes juridiques étaient citées comme obstacle empêchant les professionnels de la santé de prodiguer des soins médicaux adaptés. Au Sud-Kivu, l’opinion générale était opposée à l’avortement, avec une certaine tolérance pour les femmes allaitantes. Les principales raisons pour lesquelles les femmes avortent se rapportent à la stigmatisation et la honte, les facteurs sociodémographiques et financiers, les relations sexuelles de nature transactionnelle et le viol. Contrairement au discours critique dominant sur l’avortement, cette étude met en lumière un besoin important de services de soins d’avortement sûr. Le proverbe « mieux vaut la mort que le ridicule » montre que les femmes et les jeunes filles préfèrent risquer de mourir à cause d’un avortement à risque plutôt que rester enceintes et faire face à la stigmatisation d’une grossesse non désirée.

Resumen

El embarazo no deseado y el aborto inseguro contribuyen de manera significativa a la carga del sufrimiento materno, mala salud y muertes en la República Democrática del Congo (RDC). Este estudio cualitativo examina las vulnerabilidades de las mujeres y niñas relacionadas con el embarazo no deseado y el aborto, para entender mejor su comportamiento relativo a la búsqueda de servicios de salud y para identificar las barreras que les impiden acceder a esos servicios. Se recolectaron datos en tres áreas diferentes de la RDC oriental, utilizando entrevistas individuales a profundidad, entrevistas en grupos y discusiones en grupos focales. Las personas entrevistadas fueron muestreadas intencionalmente. Todas las entrevistas fueron grabadas en audio y transcritas palabra por palabra. Las transcripciones fueron revisadas para identificar información pertinente, codificadas manualmente y analizadas utilizando análisis de contenido cualitativo. Las percepciones y actitudes relacionadas con el embarazo no deseado y el aborto variaron en las tres áreas de estudio. En Kivu septentrional, las entrevistas reflejaron principalmente el punto de vista de que el aborto es moralmente reprensible, lo cual contrasta con la práctica extendida de aborto. En Ituri, muchas personas perciben el aborto como solución adecuada para reducir la mortalidad materna. Las limitaciones jurídicas fueron citadas como una barrera para que profesionales de salud proporcionen atención médica adecuada. En Kivu meridional, el punto de vista general era de oposición al aborto, con cierta tolerancia hacia las mujeres lactantes. Las principales razones por las cuales las mujeres tienen abortos están relacionadas con estigma y humillación, características sociodemográficas y finanzas, sexo transaccional y violación. Contrario a la narrativa crítica predominante, este estudio destaca la necesidad significativa de acceder a servicios de aborto seguro. El proverbio “Mejor muerta que objeto de burla” muestra que las mujeres y niñas prefieren arriesgarse a morir teniendo un aborto inseguro en vez de continuar con su embarazo y enfrentar el estigma por tener un embarazo no deseado.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 55.7 million abortions took place every year between 2010 and 2014, of which 25.1 million were considered unsafe. Ninety-seven per cent of unsafe abortions occurred in low and middle-income countries.1,2 Unsafe abortion is a major public health problem and contributes to maternal mortality with at least 22,800 women and girls dying every year.3,4 Unsafe abortion is the only cause of maternal death that is almost entirely preventable with access to sexual education, contraception and safe abortion care.2,5

In sub-Saharan Africa, the maternal mortality associated with abortion was 90 deaths per 100,000 live births in countries where abortion is highly restricted compared to 40 deaths per 100,000 live births in countries that allow abortion with less restrictions.6,7 When South Africa liberalised its abortion law in 1996, studies found that related maternal deaths were reduced by 91% by 2000, and the number of women suffering from infections due to unsafe abortions halved over the same time period.8

As a medical humanitarian organisation, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is committed to supporting people based on their needs by providing sexual and reproductive health services. Sexual violence care includes PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis) services, known as the “72 hours service”, mental health services and the provision of safe abortion care.5 MSF has been working in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for the last 38 years. MSF’s reproductive health and sexual violence care statistics from 2017 show that close to 13% of all reported abortion-related complications in MSF projects occurred in DRC, with over 2800 cases treated by MSF in the country that same year. Evidence from contexts with restricted access to safe abortion3,5,7,9–12 suggests that at least 50% and up to 90% of all abortion-related complications result from unsafe abortion attempts. Unsafe abortion methods include: (1) intoxications, meaning the use of herbal infusions and enemas, drinking heavily salted or soapy water or corrosive products, or the ingestion of undue quantities of medications such as paracetamol or quinine, as well as (2) mechanical methods, meaning the introduction of a foreign body into the vagina and/or uterus or external trauma to the uterus by kicking or heavy massages. The main complications of unsafe abortion are related to the use of toxic herbal treatments, bleeding, infection and trauma, including perforation of the uterus and other organs in the pelvic cavity.

The incidence of unsafe abortion is further aggravated by restrictive abortion legislation, which stands in strong contrast to its intention. Evidence indicates that restrictive abortion laws do not decrease abortion rates1,2,7 but rather criminalise abortions;13 women and girls are instead forced to end their pregnancies in secret. The legal framework regarding abortion in DRC is complex and nuanced. A 1940 Congolese penal code provision prohibits abortion unless it is performed to save the life of the woman14 which arguably limits access to abortion services.15,16 However, in 2008, DRC ratified the Maputo Protocol, an international treaty which guarantees comprehensive rights to women, including improved autonomy in their reproductive health decisions. An official communication decrees immediate application of the law in the spirit of the Maputo protocol, and extends access to safe abortion care under a number of circumstances including rape, incest and harm to a woman’s mental and physical health; in the same year, additional steps were taken to support the implementation of the Maputo Protocol in DRC.17 Given that these are recent developments, access to safe abortion services remains limited.

Even sub-Saharan African countries with liberal abortion laws face difficulties in implementing these laws in practice18 due to broader societal norms and stigma against abortion.19–21 Such restrictive policies influence how abortion services are perceived and accessed by women and girls.22,23 Societal norms further influence how health workers perceive and provide care to pregnant women seeking abortion services. Various studies from sub-Saharan Africa reflect a lack of understanding around abortion legislation by healthcare providers, as well as women and girls.24–28 A recent study published by Casey et al discussed community perceptions in relation to induced abortion and post-abortion care in North and South Kivu, and suggested the inclusion of health providers in future research.29 Healthcare providers are particularly concerned about the ambiguity of abortion legislation, because they are unsure which circumstances allow abortion services and consequently fear legal ramifications.24,27,30,31 Despite this legal ambiguity, healthcare providers from many African countries agree that unsafe abortion is a public health problem that requires liberal legislation as one strategy to prevent women from pursuing dangerous abortion methods.28,32,33

Perceptions and attitudes towards unwanted pregnancy and abortion are greatly influenced by normative and social values. Women are expected to become mothers, with motherhood strongly tied to female identity.34 Abortion is perceived as a rejection of this identity.26,29 Performing an abortion is viewed as morally wrong, and abortion has profound social consequences for women.25,35 People who have had abortions – particularly younger women – are ostracised, often branded “killers” and “prostitutes”, and are perceived as a bad influence on other women in the community.35,36 Women are further stigmatised if the man responsible for the pregnancy does not consent to the abortion, and abortion also has a negative impact on future marriage prospects.26,35,36 The anticipation of social stigma creates a culture of secrecy around abortion; women do not inform family members of their pregnancy, and are forced to self-induce an abortion or rely on services provided by unqualified individuals.29,37

Despite legal restrictions, there is a huge need for safe abortion care, as restrictive laws often push women and girls to resort to unsafe methods. Women and girls regularly approach MSF for medical help to end their pregnancies safely. While the safety of abortion is important, it is not the only concern; decision-making is also influenced by structural, economic, financial and cultural matters.3,20

In this paper, we analyse perceptions and attitudes towards unwanted pregnancies and abortions in three different health areas (Ituri, North Kivu, and South Kivu) in eastern DRC from the perspective of healthcare providers, community members and local leaders. MSF has requested the study due to the high level of abortion complications treated by the organisation in DRC and the stringent legal environment regarding safe abortion care and the critical attitude from community members and health providers. The study used an applied medical anthropological approach38 to generate better insight and understanding of how unwanted pregnancies and abortions are perceived in order for MSF to take these perceptions into account for future programming and interventions. The interpretation of data draws on social and structural factors as the key determinants for unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions.

Methods

We used a qualitative research design, as the study aim required an exploratory approach in order to understand and document perceptions and attitudes towards unwanted pregnancy and abortion among healthcare providers, community members and local leaders in DRC.39 Individual in-depth interviews, group interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs) and field notes were used to gain an insider’s perspective.40 In addition, document reviews of MSF project documents, MSF internal reports and a literature review were conducted before, during and after data collection.

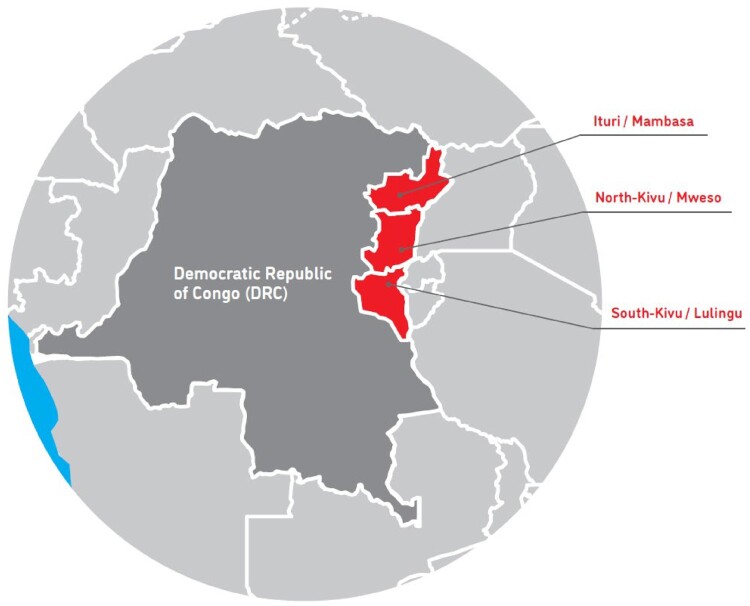

This research represents a compilation of a series of three studies conducted in three different provinces in the eastern part of DRC: North Kivu, Ituri and South Kivu (Figure 1). Data were collected between 9 May and 20 August 2017. The areas where the MSF projects are located are characterised by political instability, desperate economic conditions, and sexual exploitation in the mining areas, with a highly vulnerable population. Local people face difficult or reduced access to healthcare facilities – especially sexual and reproductive health services – and the religious, social and legal environment is not accepting of women who seek to end their unwanted pregnancies.

Figure 1.

The three study areas in the eastern part of DRC

The project in Mweso, in North Kivu, is located in a context with multiple armed groups and fluctuating frontlines. During periods of violence and instability, large numbers of people are forced to flee their homes and stay either with host families or in overcrowded displacement camps. The population is a mix of different ethnic groups including Hutu, Nande and Hunde. Because the conflict includes interethnic dynamics, it can be difficult to discuss ethnic affiliations. The project in Mambasa, in Ituri, is located in an area with specific security challenges around mining. A variety of different ethnic groups live in and around Mambasa town, including the relocated minority communities of the Bambuti (Pygmy). The project in Lulingu, in South Kivu, is located in a highly insecure environment in the middle of a dense forest, with a homogenous population comprised of one main ethnic group, the Balega.

The study population (Table 1) consisted of different groups of respondents in and around the MSF project sites: healthcare professionals (Ministry of Health [MoH] and MSF) in sexual and reproductive healthcare facilities and their various community intermediaries; key participants such as community and religious leaders; local authorities; the general population in the area; and women who experienced sexual violence and/or abortion. Study participants were purposively sampled with the help of MSF and MoH staff, and community health workers (CHW). All interviews were held in places that participants had chosen and where they personally felt safe to discuss sensitive topics, either at their workplace or in the communities in and around the study area.

Table 1.

Study population

| Respondent type | DRC | North Kivu | Ituri | South Kivu | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | |

| MSF staff | 17 | 17 | 34 | 8 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Medical | 24 | 10 | 8 | 6 | ||||||||

| Non-medical | 10 | 3 | 6 | 1 | ||||||||

| MoH staff | 22 | 17 | 39 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 9 | 16 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| Local leaders | 12 | 33 | 45 | 4 | 13 | 17 | 2 | 14 | 16 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Religious | 8 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||

| Authorities | 37 | 14 | 14 | 9 | ||||||||

| Community members | 78 | 55 | 133 | 16 | 17 | 33 | 38 | 24 | 62 | 24 | 14 | 38 |

| Youth | 35 | 16 | 51 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 20 | 6 | 26 | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| VSVa | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Teenage mothersb | 13 | 8 | 5 | |||||||||

| General population | 43 | 39 | 82 | 8 | 13 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 36 | 17 | 8 | 25 |

| Sum total | 129 | 122 | 251 | 37 | 38 | 75 | 54 | 54 | 108 | 38 | 30 | 68 |

Victims of sexual violence.

Teenager at the first pregnancy.

The study team conducted 122 in-depth individual interviews (43 in North Kivu, 41 in Ituri and 38 in South Kivu) and 34 group interviews (9 in North Kivu, 20 in Ituri and 5 in South Kivu) and four FGDs. Group interviews consisted of two to five participants with a total of 105 participants (Table 2) and FGDs were with six participants each. The study sample consisted of 251 individuals in total; the sample size was guided by a variation of diverse groups of respondents of different age, gender, ethnical affiliation and personal background, by diverse locations in the three study areas and by the notion of saturation among the various target groups and the three areas. A purposive sampling method was adopted to recruit participants for the study. People of different ages, ethnic groups and geographical regions were selected and interviewed about their perceptions, attitudes and personal experiences related to unwanted pregnancies and abortions.41 This approach enabled triangulation of the results from each participant group, comparing how they concurred and diverged in terms of findings. The selection of participants was guided by convenience, with the help of medical and psycho-social staff, for girls and women with sexual violence, unwanted pregnancy and abortion experience. Community members, local authorities and health staff were purposively selected with the help of MSF staff, the two interpreters and community intermediaries like local chiefs, community health worker etc. who linked the team with selected individuals or groups.

Table 2.

Type of interview and study participant’s profile

| Interview type | Total interviews = 160 | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual interview | 122 | 76% |

| Group interview | 34 | 21% |

| Focus group discussion | 4 | 3% |

| Interviewee profile | Total interviewees = 251 | |

| Age | N | % |

| <25 years | 52 | 20.7% |

| 26–<44 years | 150 | 59.8% |

| > 45years | 49 | 19.5% |

| Education | N | % |

| High | 103 | 41.0% |

| Low | 55 | 21.9% |

| Medium | 73 | 29.1% |

| None | 20 | 8.0% |

Data collection

The lead author, a female European medical anthropologist, conducted the in-depth individual and group interviews and focus group discussions with the help of local female and male interpreters. Individual interviews were conducted for rather sensitive subjects and group interviews and FGDs were chosen when it was intended to encourage individuals to discuss in a group to generate ideas on the research topics and to trigger participation through those ideas. All conversations except one were audio-recorded with permission from the participants. Additionally, handwritten notes were taken. A research assistant transcribed the interviews into French. The data were converted into electronic versions which were password-protected for safety and confidentiality purposes. Original quotes from the interviews were transcribed verbatim into French and translated into English by an anthropologist. Interviews began with a very general question on women’s health problems and, in most cases, respondents brought up unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortion problems without prompting. The topics were structured in a way to build trust and rapport with respondents, with more emotive questions coming later in the interview. This topic guide was flexible to avoid the conversation taking on a “vertical” nature. The researcher followed on the answers the interviewee gave to further explore the information. Topics comprised sexual and reproductive health; reasons for unwanted pregnancies, perceptions towards women and girls who experienced unwanted pregnancies; attitudes towards induced abortion, the individuals seeking it and those providing it (including healthcare providers’ attitudes).

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted by the lead author, then discussed with the study assistant and co-authors for accuracy and quality assurance. The manual analysis involved a thematic content analysis. Themes that guided this analysis included perceptions regarding sexual violence-related pregnancies, reasons and conditions that gave rise to unwanted/unintended pregnancies; perception of abortions and what factors influence these perceptions and attitudes from the perspective of communities, local authorities and healthcare providers, and what access women and girls have to safe abortion care. Transcriptions were screened for relevant information, and subsequently organised, coded, categorised and interpreted. A category (label) was attached to the statements in order to structure the data.42 The content was analysed in two ways: describing data without latent analysis; and interpretatively by focusing on the inherent meaning behind the responses.43

In order to work with the principles of good practice, validity of data was ensured by presenting a thick (dense) description of the research context and also by presenting atypical cases.44 Validity of data was further enhanced through triangulation: data from in-depth individual interviews were combined with group interviews, FGD and document reviews41 to corroborate information from these different sources; emergent themes were tested by examining exceptions and counter examples.

Ethics

The study protocol (ID 1964) was approved by the MSF Ethics Review Board and the Ethical Committee of the University in Kinshasa, École de Santé Publique.

Informed consent was obtained, either in verbal or written form, from all respondents in the study. Participants’ confidentiality was respected and the data obtained through in-depth interviews were anonymised without inclusion of any personal identifiers.45

Results

Four main themes emerged from the interviews: (1) sexual violence and transactional sex as the main factors contributing to unwanted pregnancies; (2) stigma and shame influencing the decision to undergo an abortion; (3) variations in perceptions and attitudes towards abortions in the three study areas and; (4) barriers to accessing healthcare.

Sexual violence, transactional sex and unwanted pregnancies

Many participants suggested that important contributing factors to unwanted pregnancies in all three study sites are sexual violence and transactional sex (sex that is exchanged for money and/or gifts). When women face an unwanted pregnancy, they do everything they can to clandestinely “remove it”, and young girls or students usually do not inform their family out of fear of rejection.

Sexual violence and the stigma resulting from it

Several respondents reported that sexual violence was the main cause of unwanted pregnancies, with domestic sexual violence increasingly contributing to unwanted pregnancies. Victims of sexual violence are highly stigmatised – regardless of their marital status – and stigma also affects the family as a whole. Most husbands would abandon their wives if they knew that they had been raped, hence married women hide it and if pregnant try to abort.

“It is always these [sexual] violence(s) that cause arguments among people [a couple]; you were fine with your husband, but when you are taken [raped] by these ‘forest people’ [armed groups], your home [relationship with your husband] is lost.” (Group interview, international NGO, South Kivu)

Participants stated that women are blamed for having experienced sexual violence and made to feel guilty for what happened, with rape perceived as a dishonour. A woman in a group discussion said: “When you were raped, you destroyed the house”. Men also hold women responsible for having unwanted pregnancies as a result of rape. For girls and young unmarried women who fall pregnant following sexual violence, the shame and stigma double. They feel embarrassed about the rape and for the resulting pregnancy. Furthermore, when the pregnancy has no “owner”, it is considered a disgrace for the woman and her marriage prospects are damaged.

“The pregnancy that has no ‘owner’, the woman is considered a prostitute who picked up the pregnancy in the streets; she is not respected. In street language we say that she is a goat. A goat starts the pregnancy in the streets, she doesn’t know who is responsible. The woman, in search of her honour tells herself: I have to have an abortion to keep my dignity.” (Man, 31 years, South Kivu)

Transactional sex and associated reasons

Transactional sex was mentioned by some respondents as another important factor adding to the prevalence of unwanted pregnancies. In the absence of marriage prospects and/or sustainable support from their spouse, many young girls, students, unmarried women with children, married women left on their own and widows end up engaging in transactional sex as a way to make ends meet.

“I started ‘loving’ [having sex] because the man would buy clothes for me; he would not do that for free; my parents had nothing. I only do this [sleeping with men] because life is difficult. I don’t know how to live, how my parents should live, because there [sleeping with men] I will find some ‘salt’ [food].” (Woman who had her first pregnancy as a teenager, now 28 years, South Kivu)

Long-lasting and ongoing political instability has left its mark on social relations and traditions. These relationships, determined by women’s lack of autonomy and men’s power and perceived superiority, contribute significantly to unwanted pregnancies in marriage:

“The woman is first of all an instrument of pleasure for the man. When you are in need of a woman, or you need to be satisfied on the spot, you have to look for a woman, no matter which one, that is a bit the thinking here. And again, the idea we have about a woman – that she is a weak person, inferior compared to men. So, one can abuse them as one likes because one knows that I, the man, am always superior; I have a right over her, she belongs to me.” (Male healthcare provider, 45 years, Ituri)

Some women said that marriage is limited to sexual intercourse and cohabitation. When married women are not adequately cared for (financially), it pushes them into transactional sex.

Paradoxically, some people said that healthcare workers who provide abortions occasionally ask women for sexual intercourse when the woman is unable to pay for high abortion costs:

“Others compensate the people [who provide abortions] with their bodies. [I want an abortion] I have no money, you ask me for 50 dollars [for the abortion], but I have only 20 dollars. You tell me: Ok, give me the 20 dollars and have sex with me. These things are done secretly, because the person who wants an abortion, her aim is to abort, because the people should not know that she is pregnant, so she is exposed to such abuse.” (Man, 31 years, South Kivu)

The root cause of transactional sex (in and outside marriage) is the difficult living conditions faced by women and girls who feel they have little other choice. Several women and girls reported a lack of knowledge of the menstruation cycle and difficulties in obtaining contraceptives. With this in mind, unwanted pregnancy as a result of transactional sex is preventable with good access to sexual education and contraception.

Stigma and shame influencing the decision to undergo an abortion

Several factors reportedly contributed to people’s decision to undergo an abortion ranging from having too many children, lack of access to contraceptives, pregnancy resulting from sexual violence and difficult intimate relationships with partners. Three major factors related to stigma and shame are presented in this section.

Stigma against unmarried pregnant women

Unmarried pregnant women are often confronted with stigma and shame. Ongoing stigma within families and communities is often related to socio-cultural reasons and unmarried women with children are rejected by society.

“The idea to have an abortion came to my mind because if I continue with this pregnancy, I will not go back home, I will only wander in nature because no one can take me in at their home with this pregnancy [being unmarried].” (Woman, 20 years, North Kivu)

People talk negatively about a pregnant young girl; she has a bad reputation, loses her value and dignity and is confronted to disregard and shunning.

“The stigma are the rumours that people spread in the public. Rumours are always there. She is even not respected in her home. It is all this, stigma will prevent her from having a good life.” (Religious leader, 36 years, Ituri)

“Stigma now is disregard, in fact it [the stigma] is giving you less value, yes that is it.” (Male authority, 35 years, North Kivu)

This general attitude, expressed in numerous interviews, was also brought up in a group discussion with men who said that women prefer dying than being mocked with an unwanted pregnancy:

“There is an aphorism that says: Better dead than being mocked. She might fear death, but she thinks: if I stay like this, without ‘owner', without husband, I can be mocked. It’s better to do like that [have an abortion]. She does it [because she feels she has no choice]. But she knows well that it is death, it is dangerous, but she does it to avoid being ridiculed, being seen badly.” (FGD, young men, South Kivu)

Falling pregnant while breastfeeding a child

Falling pregnant while breastfeeding a child was reported by some respondents to be a taboo for married women and very much observed among the Balega (ethnic group in South Kivu). When this happens, women will try to have an abortion by any means necessary, and abortion was stated to be socially and culturally “accepted” in such cases. Additionally, abortion is even recommended in order to protect the breastfeeding child and avoid shame.

“If the mother falls pregnant again and her baby [that she breastfeeds] is still too small, there is a risk the baby could die. If the mother realises that she is pregnant, and she has another child aged two or three months, she’ll opt for the abortion in order to protect the baby that is already there.” (Female legal advisor, 28 years, South Kivu)

Father of the child is unknown

The importance of children knowing their fathers was continuously emphasised by participants in the study. This was the most significant consequence associated with sexual violence-related pregnancy. It was commonly reported that a child from such a pregnancy would not be able to attribute her/his identity to her/his father – and children are named after their fathers. A child without a father is automatically stigmatised.

“The child will have a different character; when the child grows up and learns that his mother was raped and that he was conceived during this act, this hurts him. People make the situation worse by calling him names because this child has no known father. We often nickname the child after the armed group that was active at the time when his mother was raped.” (Women’s group leader, 43 years, North Kivu)

Variations in perceptions of abortions between study areas

Community perceptions and attitudes concerning termination of pregnancy

The perceptions and attitudes of interviewees towards abortions differed greatly in the three study areas. Regarding the legal situation, similar viewpoints were identified, alongside a more open attitude towards aborting a sexual violence-related pregnancy.

In the majority of interviews in North Kivu, questions regarding the perception of medical care for termination of pregnancy were met with outrage. Medical care for termination of pregnancy (to reduce risks related to unsafe abortions) was seen as an unacceptable option. The responses in almost all the conversations were negative. People used words like “crime”, “killing”, “murder” and “sin” when talking about termination of pregnancy.

“Inducing an abortion … that’s not good. This is not acceptable because that’s murder. For us Congolese, we even have Article 153 and 154 if we induce an abortion, it is punishable and we can get sentenced to 20 years. Based on the belief, even in front of God, it’s not good to have an abortion.” (FGD, men, North Kivu)

Despite the moral outrage and negative language used to describe how people perceive abortions, unsafe abortions were widely practiced in North Kivu.

In Ituri however, a different attitude was observed. Most people perceived and considered medical care for termination of pregnancy an appropriate solution for reducing maternal mortality and morbidity, if only the law would allow it. Fears of legal ramifications for performing or seeking abortion were expressed but did not hinder individuals from seeking care.

“There are girls who experience unwanted pregnancies. They’ll find out how to abort those pregnancies with pharmaceutical products or with traditional products; they drink leaves or do purges and sometimes this causes death … they look for someone who can advise them [about medical abortion]; they are ready for that; they ask if MSF can help in that sense.” (Male CHW, 48 years, Ituri)

In South Kivu, perceptions towards abortion were mixed and approached with caution. Community members mostly referred to the Lega culture (Balega people), to the law and to religion when discussing abortion. Although respondents viewed termination of pregnancy as challenging – mainly because Lega culture condemns abortion – it was not perceived as inhumane. Interviewees distanced themselves from forming a personal opinion, and instead used their Lega ethnic background to answer questions around perceptions of abortion.

“This is a taboo of the [Lega] tradition, because you are a killer, you are a murderer, you kill people. The one who aborts, kills; that’s how it is seen here according to the tradition. And if we see a woman that aborts, this is not a woman.” (Female psycho-social staff, 44 years, South Kivu)

Healthcare provider perspectives

In North Kivu, a number of healthcare providers expressed their wish to help but felt limited by legal restrictions. Staff from different health structures stated that they were blocked by the law from helping women and girls who seek abortion care. Others said they had convinced women or girls to keep their pregnancy without morally judging them for not wanting the pregnancy. Some respondents saw abortions as a criminal act and condemned any form of termination of pregnancy. Their reasons were based on moral and religious arguments.

“Here, as soon as you are pregnant and you have an abortion, that’s … a loss of a human life; it’s a crime, she killed [the baby]. For a two-month pregnancy, if we know that she had an abortion, she can go to prison.” (Male doctor, 44 years, North Kivu)

In Ituri, the perspective of healthcare providers regarding access to medical care for termination of pregnancy, tended to be more positive. While it was not directly declared during the conversations, it was indirectly understood that many of them had performed abortions themselves, including doctors and nurses, even though legal concerns persisted.

Health staff explained the difficult situation in the country due to ethical, moral, religious and legal reasons, which often impeded the provision of safe abortion care. They were forced to send women with abortion-related complications away (who previously asked for an abortion and had resorted to unsafe methods).

“ … instead people have things done secretly, and there are disastrous consequences […] we lost a lot of people. We already received many who were dead, who were dying, who passed away in our hands. There are others where we managed to do a hysterectomy after a major infection of the uterus or when you find that the uterus is practically rotten and necrotic – a young girl of 18-years-old with the uterus cut off, what a future! If we just could do a medical abortion.” (Male doctor, 45 years, Ituri)

In South Kivu, young men explained that hospital-level personnel refused to perform abortions, either because they were afraid of legal ramifications or due to personal reasons.

“Because they [medical staff] respect the law of the country. Because if it was known that he had [performed] an abortion at the hospital, he knows it would cause problems at work [loss of job] and he’d be arrested.” (FGD, young man, South Kivu)

Some medical staff were more sympathetic when pregnancies were related to rape. “Socially accepted” abortions (e.g. pregnant with breastfeeding child) could be accessed in some public health structures, but the husband usually had to sign a form in order to avoid legal repercussions for the medic who performed the abortion.

Barriers to accessing health care

Reported barriers to accessing healthcare services included stigma, abduction by armed groups, inability to pay, fear of repercussions as well as legal constraints and moral attitudes in general. Abortion costs were said to range from between $40 and $300 (USD) depending on where, how, and by whom the abortion is performed, and the negotiation between the person who asks for it and the one who provides the abortion.

People reported that although attacks by armed groups have decreased, they are still widespread. Access to the “72 hours service” for victims of sexual violence is hindered for women or girls who have been abducted, or those who cannot reach a health facility because of severe injury and geographical limitations. Victims of sexual violence were often afraid to access sexual and reproductive health services because they had not informed their husband, feared the attitudes of medical staff, or were threatened by the perpetrator. In many interviews, prevailing stigma hindered women and girls from accessing care after rape.

“When a woman is raped, she is automatically chased away; meaning she will lose her home, even if she has been raped. She’ll keep silent so that her husband won’t chase her away. That’s the first delay to healthcare within the ‘72 hours service’.” (Male non-medical staff, 31 years, South Kivu)

Discussion

As the findings in the section above illustrate, unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions are the results of a complex web of social and structural factors which inform people’s perceptions and attitudes. The different themes intersect with sexual violence and transactional sex as the main contributing factors for unwanted pregnancies leading to stigma and shame. This stigma and shame influence the decision to terminate a pregnancy and affect how women and girls can access safe abortion care, which is corroborated by community and health workers’ perceptions and attitudes.

The reasons behind abortion are complex and reflect the traditional relationship between men and women, social constraints, traditional values and difficult living conditions in general. References to “unmarried” or “young” women, (unfaithful) married women and “prostitutes” when the question of abortion was approached show that public views are mirrored by moral and judgmental attitudes. These women and girls do not “comply” with the social and gender norms expected of them: marriage and motherhood.19–21 Women and girls who plan or have an abortion, are morally condemned because they do not fit society’s ideal of a woman being a mother and bearing many children. A Congolese proverb says: “A woman without children does not die, she disappears.” In other words, she never existed.

The interviews highlighted a significant lack of decision-making power and agency for women with respect to their sexuality, both in and outside marriage. The predominant understanding of marriage is related to the duty to satisfy the husband's demands and expectations (sex, children, faithfulness). Outside marriage, sexual and social violence (stigma, poverty, isolation from the family) push women and girls into transactional sex to make ends meet and provide for their families.46 Formson and Hilhorst describe transactional sex as a coping mechanism in adverse socio-economic situations.47 Interviewees brought up several different factors regarding unwanted pregnancies and abortion and they recognised society’s rejection of pregnant unmarried women. Premarital childbearing is shameful because premarital sex is shameful, and young girls go to extreme lengths to avoid these situations and protect their future marriage prospects. An abortion is often viewed as “the lesser shame”, as suggested by Johnson-Hanks48 in her research in southern Cameroon. Johnson-Hanks found that educated women were resorting to unsafe abortions because it bore “lesser shame” than “a severely mistimed entry into socially recognised motherhood”.48 Unwanted pregnancy becomes an even greater burden if it is related to sexual violence, particularly for women and girls who fall pregnant as a result of rape. The stigma attached to a sexual violence-related pregnancy was highlighted as a key factor regarding the decision to have an abortion. These situations, especially sexual violence-related pregnancies, seem to evoke some empathy from society in terms of providing safe abortion care, as also reported by Casey.29

Access is difficult because women do not want to be seen asking for an abortion. When it is known that they have experienced an abortion they are stigmatised again for this; young girls do not want to be seen to be pregnant and do not inform anyone out of shame (mainly after sexual violence). Many are afraid asking for an abortion, or simply do not know where they can ask for a safe abortion or are afraid that the community may find out they have experienced an abortion.

References to the church, religion and church leaders were frequent and did not project a particularly empathetic view of the challenges that women face. The references seem to mirror the stigma women are subjected to at large, be it related to sexual violence, pregnancy out of wedlock, contraception, transactional sex or abortion.

In the context of ongoing conflict, as is the case in Eastern DRC, social relations, especially between men and women, change. The political instability also left its mark on social relationships and economic precarity has led to an increase in transactional sex to acquire financial means. In addition, in DRC the law prohibits abortions unless the life of the woman is in danger, causing fear of legal repercussions and forcing women to seek abortions under unsafe conditions.

These social and structural factors intersect in stark ways, leading to the perceptions and attitudes presented above. Stigma and shame inform both a women’s decision to have an abortion and access to safe abortion care. The high number of induced abortions – in almost all cases performed under unsafe conditions – reflects the situation for women and girls regarding their sexual and reproductive health. In all three study areas, financial means improve access to safer abortion methods. This is consistent with other studies, where decisions to have unsafe abortions were influenced by socio-economic factors.49–51 An understanding of the complex association between social and structural factors that lead to unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions recognises the need for a multi-layered response. Issues related to sexuality, contraception, unwanted pregnancy and abortion remain taboo but are relevant for discussions at all levels in the community and with health staff. These topics are considered acceptable to talk about when the subject is approached in a non-judgmental way. Interviews indicated an urgent need to foster dialogue on sensitive issues regarding contraception and abortion as MSF’s next steps. While most of the respondents viewed induced abortions as immoral or criminal, they also expressed the need to prevent unsafe abortions and the importance of safer, legal ways to end unwanted pregnancy.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study included the sensitivity of the topic because of the restrictive Congolese abortion law, and the level of discomfort in talking about personal experiences. This limitation was reduced to a minimum by not talking directly about termination of pregnancy at the start of the interviews, but rather asking questions about problems related to sexual and reproductive health (which in most cases led to the subject of abortion). Another limitation was that the translators were identified as MSF which potentially created response bias. This risk was minimised through careful explanation of the researcher’s role and her neutrality, and strict assurance of anonymity and confidentiality. Finally, all interviews took place in locations where MSF runs long-standing health projects and provides reproductive health care and care for victims of sexual violence.

Conclusion

Unsafe abortions happen regardless of legal, moral and social restrictions. The reasons why women and girls want or are forced to undergo abortions are complex: traditional values and the stigma and rejection women face when their pregnancies do not conform with social expectations; difficult living conditions; the traditional relationship between men and women; and socio-economic constraints. The proverb, “better dead than being mocked” reflects just how challenging the situation is; women and girls would rather risk dying by undergoing an unsafe abortion, than keeping the pregnancy and being mocked for it. Abortion is seen as one way to prevent the dishonour of keeping an unwanted pregnancy.

Several policy and practice recommendations can be drawn from this study. First, the results of this study are intended to help improve the attitude towards and treatment of women who have abortions, and identify measures to reduce the burden of unsafe abortion-related complications and maternal death. Second, these results are intended to inform MSF operations and raise awareness of one of the most important and entirely preventable causes of maternal mortality. Third, the study highlights the importance of reinforcing community knowledge and access to relevant services, particularly care for victims of rape: contraceptive services and safe abortion care. Finally, the study is an important reminder that despite the recent changes in legal provisions regarding abortion, access to safe abortion care in DRC is far from achieved. A more liberal legal frame is an important prerequisite to change. However, access to safe abortion care for women and girls in DRC will depend on healthcare provider attitudes and capacity, as well as access to information and stigma reduction.

In the last two years, MSF has made important advances in improving access to safe abortion care in DRC; addressing provider attitudes and improving clinical knowledge and skills have been key, alongside improved dialogue at all levels, better understanding of risks and threats and systematic data collection.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the people in North Kivu, Ituri and South Kivu who talked to us and made this study possible. Our gratitude goes out to all the women, men, girls and boys who were willing to share their experiences and thoughts and gave MSF better insight into perceptions of unwanted pregnancy and abortion and the actions necessary to improve care. We would like to thank the MSF and MoH teams in the three projects for their valuable support and their professional attitude. A special thanks goes out to the local authorities in DRC, the Ethical Committee of the University in Kinshasa, the École de Santé Publique, and to the MSF ethical review board for validating this study. Finally, we are grateful to our colleagues in the Vienna Evaluation Unit, to the colleagues at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto and to the International MSF Office in Geneva for their professional guidance throughout the entire study process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Sedgh G, Bearak J, Singh S, et al. Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: global, regional, and subregional levels and trends. Lancet. 2016;388:258–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2372–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S, et al. Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic. Lancet. 2006;368:1908–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh S, Remez L, Sedgh G, et al. Abortion worldwide 2017: uneven progress and unequal access. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulte-Hillen C, Staderini N, Saint-Sauveur JF.. Why Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) provides safe abortion care and what that involves. Confl Health. 2016;10:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebremedhin M, Semahegn A, Usmael T, et al. Unsafe abortion and associated factors among reproductive aged women in sub-Saharan Africa: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO . Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson J. Evaluating abortion-care programs: old challenges, new directions. Stud Fam Plann. 2005;36(3):189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berhan Y, Berhan A.. Causes of maternal mortality in Ethiopia: a significant decline in abortion related death. Ethiopian J Health Sci. 2014;24:15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kismödi E, de Mesquita JB, Ibañez XA, et al. Human rights accountability for maternal death and failure to provide safe, legal abortion: the significance of two ground-breaking CEDAW decisions. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGinn T, Casey SE.. Why don’t humanitarian organizations provide safe abortion services? Confl Health. 2016;10(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MDM . Unwanted pregnancies & abortions: comparative analysis of sociocultural and community determinants. Paris: Médecins du Monde; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sangala V. Safe abortion: a woman's right. Trop Doct. 2005;35(3):130–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalonda JC. Sexual violence in Congo-Kinshasa: necessity of decriminalizing abortion. Rev Med Brux. 2012;33(5):482–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burkhardt G, Scott J, Onyango MA, et al. Sexual violence-related pregnancies in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: a qualitative analysis of access to pregnancy termination services. Confl Health. 2016;10(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casey SE, Gallagher MC, Makanda BR, et al. Care-seeking behaviour by survivors of sexual assault in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1054–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lwamba Bindu B. Circulaire N° 04. Republique Democratique du Congo, Conseil Superieur de la Magistrature: DRC; 2018.

- 18.Rehnström Loi U, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Faxelid E, et al. Health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levandowski BA, Kalilani-Phiri L, Kachale F, et al. Investigating social consequences of unwanted pregnancy and unsafe abortion in Malawi: the role of stigma. Int J Gynecol Obstetrics. 2012;118:S167–S171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izugbara CO, Egesa C, Okelo R.. ‘High profile health facilities can add to your trouble’: women, stigma and un/safe abortion in Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2015;141:9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rouhani SA, Scott J, Greiner A, et al. Stigma and parenting children conceived from sexual violence. Pediatrcis. 2015;136:1195–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nara R, Banura A, Foster AM.. Exploring Congolese refugees’ experiences with abortion care in Uganda: a multi-methods qualitative study. Sexual Reprod Health Matter. 2019;27(1):262–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deitch J, Amisi JP, Martinez S, et al. “They love their patients”: client perceptions of quality of postabortion care in North and South Kivu, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(Suppl 2):S285–S298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aniteye P, O'Brien B, Mayhew SH.. Stigmatized by association: challenges for abortion service providers in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill ZE, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Kirkwood B.. The context of informal abortions in rural Ghana. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(12):2017–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marlow HM, Wamugi S, Yegon E, et al. Women's perceptions about abortion in their communities: perspectives from western Kenya. Reprod Health Matters. 2014;22(43):149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payne CM, Debbink MP, Steele EA, et al. Why women are dying from unsafe abortion: narratives of Ghanaian abortion providers. Afr J Reprod Health. 2013;17(2):118–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voetagbe G, Yellu N, Mills J, et al. Midwifery tutors' capacity and willingness to teach contraception, post-abortion care, and legal pregnancy termination in Ghana. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casey SE, Steven VJ, Deitch J, et al. “You must first save her life”: community perceptions towards induced abortion and post-abortion care in North and South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sexual Reprod Health Matter. 2019;27(1):1571309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harries KS, Orner P.. Health care providers' attitudes towards termination of pregnancy: a qualitative study in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morhe ES, Morhe RA, Danso KA.. Attitudes of doctors toward establishing safe abortion units in Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstetrics. 2007;98(1):70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aniteye P, Mayhew SH.. Shaping legal abortion provision in Ghana: using policy theory to understand provider-related obstacles to policy implementation. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdi J, Gebremariam MB.. Health providers' perception towards safe abortion service at selected health facilities in Addis Ababa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2011;15(1):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiweshe M, Mavuso J, Macleod C.. Reproductive justice in context: South African and Zimbabwean women’s narratives of their abortion decision. Fem Psychol. 2017;27(2):203–224. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plummer ML, Wamoyi J, Nyalali K, et al. Aborting and suspending pregnancy in rural Tanzania: an ethnography of young people's beliefs and practices. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39(4):281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yegon EK, Kabanya PM, Echoka E, et al. Understanding abortion-related stigma and incidence of unsafe abortion: experiences from community members in Machakos and Trans Nzoia counties Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webb D. Attitudes to “Kaponya Mafumo”: the terminators of pregnancy in urban Zambia. Health Policy Plann. 2000;15(2):186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pool R, Geissler W.. Medical anthropology. London: McGraw-Hill Education; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pope C, Mays N.. Qualitative research in health care. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris M. History and significance of the EMIC/ETIC distinction. Annu Rev Anthropol. 1976;5(1):329–350. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green J, Thorogood N.. Qualitative methods for health research. London: Sage; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. Weinheim: Beltz Verlag; 2010. p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hancock B. Trent focus research and development in primary health care. An introduction to qualitative research 2002. Sheffield, University of Nottingham: Trent Focus; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geertz C. Thick description: toward an interpretative theory of culture. In: Clifford Geertz, editor. The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books; 1973. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richards HM, Schwartz LJ.. Ethics of qualitative research: are there special issues for health services research? Fam Pract. 2002;19(2):135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silberschmidt M, Rasch V.. Adolescent girls, illegal abortions and “sugar-daddies” in Dar es Salaam: vulnerable victims and active social agents. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(12):1815–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Formson C, Hilhorst DJM.. The many faces of transactional sex: women's agency, livelihoods and risk factors in humanitarian contexts: a literature review. London: Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson-Hanks J. The lesser shame: abortion among educated women in southern Cameroon. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(8):1337–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arambepola C, Rajapaksa LC.. Decision making on unsafe abortions in Sri Lanka: a case-control study. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scott J, Onyango MA, Burkhardt G, et al. A qualitative analysis of decision-making among women with sexual violence-related pregnancies in conflict-affected eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chae S, Desai S, Crowell M, et al. Reasons why women have induced abortions: a synthesis of findings from 14 countries. Contraception. 2017;96(4):233–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]