Abstract

Maternal health (MH) is a national priority of Morocco. Factors influencing the agenda set by the reproductive and maternal health policy process at the national level were evaluated using the Shiffman and Smith framework. This framework included the influence of the actors, the power of the ideas used, the nature of the political context, and the characteristics of the issue itself. Factors were evaluated by a review of documents and interviews with policy-makers, partners and individuals in the private sector, civil society and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) involved in MH, and decision-makers responsible for implementing health-financing strategies in Morocco. Evaluations showed that maternal mortality in Morocco was considered human rights and social development as well as a public health problem. The actors responsible for MH, including members of the government, researchers, national technical experts, members of the private sector, United Nations partners and NGOs, agreed on progress made in MH and universal health care (UHC). Stakeholders also agreed on the prioritisation process for MH and its inclusion in the health benefits package. Prioritisation of MH was found to depend on national health priorities set by the government and its close partners, as well as on the availability of human and financial resources. Interventions at the operational level were based on evidence, best practices, allocation of adequate financial and human resources, and rigorous monitoring and accountability. However, MH and health financing are experiencing difficulties in many areas, related to social and economic and health disparities, and gender inequality, and quality of care.

Keywords: maternal health, sexual and reproductive health, human rights, universal health coverage, prioritisation, health benefits package

Résumé

La santé maternelle est une priorité du plan national de santé du Maroc. Les facteurs influençant le programme défini par le processus politique de santé maternelle et reproductive au niveau national ont été évalués à l’aide du cadre de Shiffman et Smith. Ce cadre tenait compte de l’influence des acteurs, du pouvoir des idées utilisées pour décrire la question, de la nature du contexte politique, des caractéristiques de la question elle-même et de la priorisation de la santé maternelle dans le panier de soins de santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR). Les facteurs ont été évalués par un examen de documents et des entretiens avec des décideurs, des partenaires et des personnes appartenant au secteur privé, à la société civile et à des organisations non gouvernementales (ONG) actives dans la santé maternelle, ainsi qu’avec des responsables de la mise en œuvre de stratégies de financement de la santé au Maroc. Les évaluations ont montré que la mortalité maternelle au Maroc était considérée comme un problème ayant trait aux droits de l’homme, au développement social et à la santé publique. Les acteurs responsables de la santé maternelle, notamment des membres du Gouvernement, des chercheurs, des experts techniques nationaux, des membres du secteur privé, des partenaires des Nations Unies et des ONG, étaient d’accord sur les progrès accomplis dans la santé maternelle et la couverture santé universelle (CSU). Ils ont aussi adhéré au processus de hiérarchisation des priorités pour la santé maternelle et son inclusion dans le panier de soins. Il a été constaté que la priorisation de la santé maternelle dépendait des priorités nationales de santé fixées par le Gouvernement et ses proches partenaires, ainsi que de la disponibilité de ressources humaines et financières. Un environnement politique favorable a encouragé le Ministère de la santé à donner la priorité à la santé maternelle en alignant les approches politiques et techniques. Les interventions au niveau opérationnel étaient fondées sur les données, les meilleures pratiques, l’allocation de ressources financières et humaines adéquates, ainsi qu’un suivi attentif et une redevabilité rigoureuses. Néanmoins, la santé maternelle et le financement de la santé connaissent des difficultés dans de nombreux domaines, en particulier ceux qui se rapportent aux disparités sociales, économiques et sanitaires, à l’inégalité entre hommes et femmes, à la qualité des soins et à la nécessité de formuler une stratégie de financement consolidé de la santé.

Resumen

La salud materna (SM) es una prioridad del Plan de Salud nacional de Marruecos. Los factores que influyen en la agenda establecida por el proceso de políticas relativas a la SM Reproductiva a nivel nacional fueron evaluados utilizando el marco de Shiffman y Smith. Este marco incluyó la influencia de los actores, el poder de las ideas utilizadas para plantear el tema, la naturaleza del contexto político, las características del asunto en sí y la priorización de SM en el paquete de beneficios de salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR). Los factores fueron evaluados por una revisión de documentos y entrevistas con formuladores de políticas, socios y personas en el sector privado, organizaciones de la sociedad civil y no gubernamentales (ONG) involucradas en SM, e instancias decisorias responsables de aplicar estrategias de financiamiento de los servicios de salud en Marruecos. Las evaluaciones mostraron que la mortalidad materna en Marruecos era considerada un asunto de derechos humanos y social, así como un problema de salud pública. Los actores responsables de SM, tales como integrantes del gobierno, investigadores, expertos técnicos nacionales, integrantes del sector privado, socios de las Naciones Unidas y ONG, estuvieron de acuerdo en cuanto al progreso logrado en SM y en la cobertura universal de salud (CUS). Las partes interesadas también estuvieron de acuerdo con el proceso de priorización de SM y su inclusión en el paquete de beneficios de salud. Se encontró que la priorización de SM depende de las prioridades de salud nacionales establecidas por el gobierno y sus principales socios, así como en la disponibilidad de recursos humanos y financieros. El entorno político favorable motivó al Ministerio de Salud a priorizar SM alineando los enfoques políticos y técnicos. Las intervenciones a nivel operativo se basaron en evidencias, buenas prácticas, asignación de recursos financieros y humanos adecuados, monitoreo riguroso y rendición de cuentas. Sin embargo, SM y financiamiento de salud están pasando por dificultades en muchas áreas, especialmente aquellas relacionadas con disparidades sociales, económicas y sanitarias, desigualdad de género, calidad de la atención y la necesidad de formular una estrategia consolidada de financiamiento de salud.

Introduction

In Morocco, national policies regarding reproductive and maternal health (RMH) have undergone several stages of evolution. The 1980s were characterised by the establishment of safe motherhood and family planning (FP) units at primary health care (PHC) facilities. Since the 1990s, issues related to the rights of individuals to receive adequate RMH services have been emphasised. Between 2000 and 2007, programmes were developed to prioritise FP and safe motherhood services. A national health action plan, involving all related departments at the Ministry of Health (MOH), was developed between 2008 and 2012 to emphasise RMH packages and delivery of RMH services. This included the development, in 2011, of a national reproductive health strategy, stressing individual rights and the integration of reproductive health (RH) components.1 A national strategy stressing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and universal health coverage (UHC) was first developed between 2008 and 2012 and accelerated between 2012 and 2016, with an emphasis in 2018 on a continuum of SRH care and UHC through 2025.2 Morocco has made significant progress in RMH during this period, with better socio-economic conditions and access to health care contributing to many improved demographic and epidemiological indicators.1 This progress resulted from an organised health care system involving three sectors: public, private non-profit, and private for-profit.2 The public sector consists of networks of healthcare facilities, including PHC facilities, a hospital network (HN), an integrated network of medical emergency care, and a network of medical-social establishments.2,3 Health coverage was improved by investing in the extension of PHC services in urban and rural settings, including medical offices, pharmacies, dental offices, hospitals and private clinics, as well as in the development of tertiary university teaching hospitals.2

The MOH has been successful in strengthening primary and secondary health care services by providing SRH care coverage along the continuum of care, and by targeting preventable maternal and child deaths.2 All these health interventions have led to a reduction in the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) from 332 per 100,000 live births in 1992 to 72.6 per 100 000 live births in 2018.4 In 2018, the neonatal mortality rate was 13.58 per thousand live births; the rate of contraceptive use was 70.8%; the rate of antenatal health care coverage was 88.5%; and 86.6% of births were attended by skilled health personnel.4

Despite these substantial advances in healthcare, limitations and challenges remain in ensuring universal RMH services, particularly health disparities between urban and rural populations, between individuals with high and low levels of education, and between individuals of high and low socio-economic status.5,6 For example, MMR rates are 2.5 times greater in rural than in urban areas, with unmet needs for FP in 11.3%.4 Moreover, national policies, regulations and strategies to date have covered only post-abortion care, not safe abortion care services, as abortion is illegal in Morocco.7 About 2.1 million women (22.6% of women in Morocco) have experienced sexual violence, with rates twice as high in urban as in rural areas.8 In addition, girls and women have difficulties accessing quality and respectful SRH care services.2,9

To attain UHC, Morocco implemented the Basic Medical Coverage Code (Couverture Médicale de Base CMB) in 2002. These steps included (i) the requirement for mandatory health insurance (Assurance Maladie Obligatoire), first implemented in 2005, based on the principles and programmes of social insurance for employed individuals, pensioners, former resistance fighters and members of the liberation army and students; (ii) a Medical Assistance Scheme for the Economically Underprivileged (Régime d’Assistance Médicale – RAMED), based on the principles of social support and national solidarity for the benefit of vulnerable and poor individuals, first implemented in 2012; and (iii) Medical Insurance for the Self-Employed (Assurance Maladie des Indépendants). This programme has improved the nationwide health insurance coverage rate to 62%, but it remains short of the goal of 90%.6,10 Collective health financing is still limited (48.8%) and households are responsible for more than half of total health expenditures.11 Total health expenditure in Morocco was ∼52 billion dirhams in 2013 (US$ 6.1 bn), or 5.9% of gross domestic product (GDP), with per capita health expenditure nearly US$188. The health system is financed by tax revenue (24.4%), households (50.7%), health insurance (22.4%), employers (1.2%) and international and other sources (1.3%).11

The RMH benefits package is part of the services covered by health insurance, with free services offered by PHC facilities, including FP services, prenatal care, intra-partum care, post-partum care, screening for and management of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV/AIDS, and screening for breast and cervical cancers. At the referral level (hospitals), RMH services are covered by health insurance schemes or paid by beneficiaries if not insured. The one exception is maternal health care, including prenatal care for delivery and caesarean section in public hospitals.12,13,14

In Morocco, maternal mortality is considered not only a public health issue, but also a human rights and social development issue.15 In 1987, Morocco ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which affirms the reproductive rights of women. Morocco also took part in the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, at which the concepts of women’s empowerment, gender equity, and reproductive health and rights were recommended. However, despite these initiatives, 89% of maternal deaths are still avoidable.17 Access to health care services is still limited for the most vulnerable groups, including those living in rural and/or remote areas, single mothers, adolescents and young people, and women with HIV.6,16,18 These individuals lack access to qualified personnel, especially medical specialists in the public sector, as there is a wide gap in MH resources between the public and private sectors.6,16 Cultural barriers, including limits to women’s empowerment and gender equity, are also barriers to MH.6,18

The prioritisation of MH started with its inclusion as a key component of the first national health action plan in 2008–2012, developed by the MOH, with the involvement of all relevant departments and key stakeholders involved in the health and well-being of the Moroccan population through strengthening of health care coverage.5 Morocco developed an action plan in 2012–2016 to accelerate the reduction of maternal and newborn mortality rates, based on the key achievements of the 2008–2012 plan and in accordance with the 2011 Moroccan constitution, which emphasised human rights and equity.19 The acceleration plan focused on adopting evidence-based, cost-effective and high impact interventions in MH,12 and stressed gender equity and woman’s rights by promoting good quality MH services with respect and dignity. MH services were maintained within the RMH benefit package and further practices were considered, such as free caesarean sections and healthcare management of pregnancy complications. The plan expanded the maternal audit to maternity services at both primary and secondary health care levels, as well as reinforcing greater equity of MH services by targeting rural and remote areas.

In 2019, Morocco developed the National Health Plan 2025, with a goal of addressing fragmentation and non-convergence of SRH programmes within the health benefits package (HBP). This plan included MH as a national priority and its integration within the SRH package, focusing on convergence between the political and technical plans, the reinforcement of joint partnership activities, and the strong involvement of civil society and community to improve women’s health and well-being.2

To understand the “why” and “how” of MH prioritisation in Morocco, this paper will examine the nature of the political context (human rights-based approach and degree of inclusion in UHC), the role of actors, the characteristics of MH, the key government decision-makers and the resources deployed to ensure the priority of MH.

Methods

Study setting

This study was performed using the Shiffman and Smith framework, which has been shown to be useful for organising and analysing data to assess health policy priorities for RMH/SRH care services.20 The framework was utilised to explore four categories: the influence of the actors involved in the initiative, the power of the ideas they used to portray the issue, the nature of the political contexts in which they operated and the characteristics of the issue itself (Table 1).20 This framework did not allow assessment of the implementation of any policy, including its reception, impact and outcomes. A fifth element, outcome, was added to the Shiffman and Smith framework to explore the key government decisions and resources allocated for the prioritisation of MH within the SRH benefit package (Table 1).21

Table 1.

Framework for assessing factors affecting the setting of a national agenda

| Elements | Description | Factors shaping policy priorities |

|---|---|---|

| Actors influence | The influence of the individuals and networks concerned with the issue |

|

| Ideas | The ways in which those involved with the issue understand and portray it |

|

| Context | The environment in which actors operate |

|

| Issue characteristics | Features of the problem |

|

| Outcome | Determination of the strength of the issue on the agenda |

|

Source: adapted from Shiffman and Smith (2007).

Study design, population and sampling

This exploratory qualitative case study was based on a desk review to map and analyse related documents regarding sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) within UHC. The study was conducted between 2019 and 2020 in Rabat, the capital of Morocco, where most health policy-makers and programme managers of SRH are located, as well as relevant policy-makers, partners, members of the private sector, and representatives of civil society and non-governmental organisations. The population surveyed included health policy-makers and actors involved in setting healthcare priorities. The purpose of the study was to identify the fundamental values related to provision of SRH services for better universal maternal health coverage in Morocco.

National stakeholders were divided into three groups:

national government stakeholders, who are responsible for defining national reproductive and maternal health programmes and the national health financing policy;

relevant partners and stakeholders, including those in the private sector, who provide both financial and technical support on health system strategies; and

civil society and non-governmental organisations involved in SRH/maternal health services.

Data were also collected from healthcare providers at different levels (operational, provincial and regional), as well as private sector providers, and decision-makers and programme managers from MOH departments (e.g. the maternal health protection service, the cooperation division, RAMED insurance service and the national health insurance agency) involved in the management of financial and support mechanisms for MH programmes and UHC.

Data collection

Primary data were obtained by interviews with key individuals and focus group discussions (FGDs), and secondary data were obtained by reviewing available MOH reports and national health documents, reports and documents published by relevant partners, and relevant independent research reports and papers published between 2000 and 2019.

All participants in interviews and FGDs provided informed consent to participate, as well as to record these sessions. These interviews and FGDs, in both Arabic and French, lasted one hour and included an expert in health sociology.

Semi-structured interview guides were developed to discuss the following key items:

profiles of the key actors at various levels of the MOH involved in setting the priority of MH within SRH and UHC plans during the reform process;

the degree of involvement of actors in MH services in setting SRH priorities;

the degree of incorporation of MH service priorities in the SRH benefit package;

the nature of policy decisions made to successfully enhance access to comprehensive and integrated RMH services.

An FGD guide was formulated based on the preliminary results of individual interviews. This guide, designed to explore several issues in depth, was tested for the comprehensiveness and completeness of the survey questions by two key resource individuals not included in the sample.

Analysis

Selected documents were analysed using the data extraction sheet (Appendix). Data collected from analysis of these documents was used to identify the stakeholders involved in the scope of the research, to clarify the data collected from interviews and FGDs, and to analyse the findings.

Records of interviews and FGDs were fully transcribed and analysed using the “content analysis” approach, which reduces the volume of text collected, identifies group categories and analyses these categories.22

The analysis consisted of three steps: transcription of interviews and FGDs, highlighting a global understanding of the interviewees’ points of view; classification of the interview and focus group data according to the items and the sub-items identified based on the research framework; and application of the sociologist’s expertise to the data obtained by analysing interviews and FGDs.

The codes from the different transcripts were reviewed while maintaining the principle of constant comparison. Codes containing similar ideas were grouped together for the development of broad themes. Data analysis was guided by framework components, including actors’ influence, ideas, context, issue characteristics and outcomes.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) Research Ethics Review Committee and from the Ethical Research Committee of the University Mohammed V in Rabat (reference No. 27/20) on 17 January 2020.

Written consent was obtained from each participant, who had been informed of the purpose of the study and of their ability to withdraw from the study at any stage. Participation in this study did not involve any risk to participants.

Results

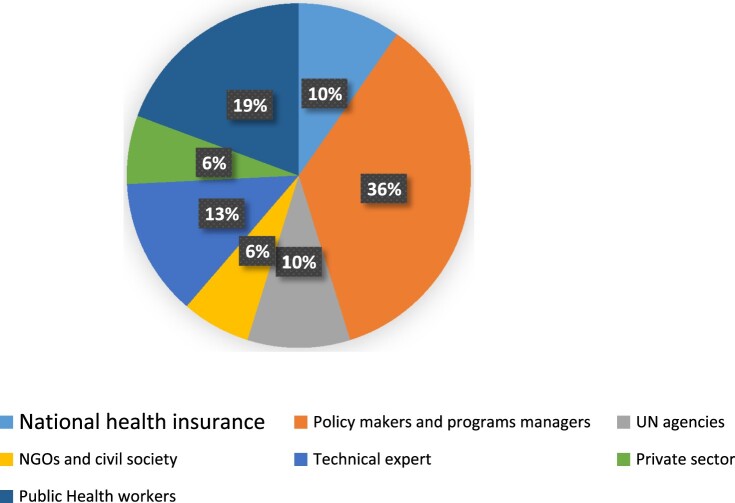

The study consisted of 31 individuals and 2 focus groups (Figure 1). The different outputs of our results followed the study framework. Specific quotations were obtained from study subjects in exploring the roles of political actors, the nature of the political contexts, the characteristics of the health issues and government decisions, and the resources allocated to ensure the priority of MH in Morocco.

Figure 1.

Areas of expertise of study interviewees

Actors’ ability to shape SRH policy priorities within the UHC

Priority-setting is a central part of building efficient, responsive and resilient healthcare systems.23 Actor influence in the Shiffman and Smith (2007) framework is defined as the relative influence of the individuals and organisations concerned with the issue. Actors influence the policy-making process through their knowledge, experiences, beliefs and influence.24

In Morocco, many actors are involved in setting MH priorities, including government workers, researchers and technical experts, members of the private sector, partners, civil society organisations and NGOs. Actors were in general agreement about progress achieved in MH and UHC, with several individuals stating that national efforts by healthcare authorities have focused on reducing maternal mortality and morbidity rates through widespread access to antenatal and obstetric care and FP services. This has led to large improvements in MH outcomes:

“ … Honestly, we are proud of the progress made regarding maternal health … as demonstrated by the related indicators. The latest 2018 family and population health survey showed that the maternal mortality rate was 72.6 per 100.000 live births, indicating an improvement trend that must be maintained … .” (MOH official)

Most interviewees mentioned the primary role of the MOH as a leader in the progress made on MH care services in Morocco. This finding highlights the vital role of politicians and decision-makers in prioritising MH to reduce maternal mortality rates:

“ … Certainly, Morocco has made major progress in the field of MH. The MOH has been engaged in a process of reforms relating to the financing and organisation of the health sector. Thus, following implementation of the 2008–2012 and 2012–2016 strategies, public policies in MH experienced a dynamic evolution and courageous and effective political decisions … .” (National reproductive and maternal health expert)

These respondents acknowledged that national health strategies have focused on reducing maternal mortality rates and that maternal mortality was considered not only a national health priority but also a non-health sector priority. Beginning in 2000, Moroccan authorities launched many activities to reduce health inequities by addressing underlying social determinants, such as poverty, illiteracy, unemployment and marginalisation. King Mohamed VI, the highest authority in Morocco, launched five main initiatives between 2000 and 2005. The first was devoted to education (the Education Charter, 2000), the second evaluated 50 years of human development in Morocco (2003), the third addressed human rights (Equity and Reconciliation Commission, 2004), the fourth concerned the Moroccan Family Code (Moudawana, 2004), and the fifth was dedicated to human development (National Initiative for Human Development, 2005).25 In particular, the Ministry of the Interior designed the National Initiative for Human Development (NIDH) to improve socio-economic conditions in targeted poor areas through new participatory local governance mechanisms and local authorities’ involvement in financing projects with a high impact on human development in all non-targeted rural and urban areas:26

“ … thanks to a multi-sector-based partnership of all the stakeholders involved in MH as part of a national effort to reduce maternal mortality rates, considered an indicator of social development … several collaborative health interventions to reduce barriers and enable economically disadvantaged persons to access MH services at public health facilities were established by the NIDH … .” (National reproductive and maternal health expert)

A priority-setting process theoretically allows various healthcare stakeholders to articulate their preferred values and agendas to achieve consensus on the direction of a country’s health agenda.27 From this perspective, the interviewed stakeholders mentioned the main role of international agencies, including UN agencies, in the policy-making process to prioritise MH as part of SRH within the health benefits package (HBP), based on international norms and guidelines. Thus, most stakeholders expressed diverse comments about the process of MH prioritisation and its inclusion within the HBP. A respondent from a UN agency mentioned the importance of MH as a key component of SRH towards UHC:

“ … we have supported the MOH for years in various components of RMH and UHC … Morocco has experienced great progress in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality rates. We have supported the national strategy of the MOH for eliminating preventable maternal mortality and in the preparation of regional action plans to adapt the national strategy to regional specificities. We continue to provide technical and financial support for improving the quality of maternal and newborn health care at health facilities … .” (Member of a UN agency)

UN partners have recognised MH as a key component of an SRH package, based on a human rights approach and gender equality, as expressed by this respondent:

“ … To achieve universal access to SRH, promote reproductive rights, monitor population dynamics, and adopt a human rights approach and gender equality, we have supported the MOH in the field of maternal health, because we believe that no woman should lose her life or be threatened by preventable morbidities related to pregnancy or childbirth … .” (Member of a UN agency)

Further, prioritisation of MH in an SRH package is dependent on government-expressed national health priorities, as well as convergence with available resources. Following joint advocacy with its partners and policy-makers, Morocco established a joint action plan (H4+), which includes the WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and UNAIDS, targeting priority regions to accelerate the achievement of the MDGs.

Sexual and reproductive health, including MH and reducing maternal mortality, is an area in which NGOs have historically been pioneers. NGOs have been involved in the implementation of activities dealing with MH issues, especially FP and screening for breast and cervical cancer and HIV/AIDS. Among these activities has been the implementation by the Morocco Coordinating Committee on AIDS and Tuberculosis of participatory planning as part of the AIDS program.28,29 This committee is composed of various NGOs, as well as the MOH, which has no power over other members. As explained by the representative of the MOH:

“In this committee, planning takes place in a consensual manner in coordination with the financial partner, which is the Global Fund. There are even key populations that are represented in the CCM. We wish to extend this experience to vertical programmes for pregnant women, young people, … .” (Programme manager, MOH)

The private sector has not yet been integrated at the strategic level in SRH policy or programmes. Non-integration is a structural problem of the Moroccan healthcare system. The private sector is generally unregulated, its activities are rarely documented and it is relatively uninvolved in sectoral health strategies dealing with MH:2,12,13

“ … We need more involvement of the private sector as an important partner of the national health system … in order to contribute to establishment of national health priorities … .” (Clinic director, Private sector)

Successes in MH generally resulted from political will and commitment, as well as joint efforts by policy-makers, programme managers and UN partners. However, these interviews found that more work is needed to ensure coherence of the policy community and to strengthen the leadership of the MOH in fulfilling the requirements towards the SDGs and to maintain the high political commitment to MH.

Actors’ ideas regarding MH prioritisation within the HBP

The ideas advanced by actors were extremely useful in identifying the way an issue is understood and portrayed.20,21 Of the 31 participants, 26 mentioned that over the past 12 years (2008–2020) in Morocco, politicians and decision-makers have had a great impact in prioritising MH to reduce maternal mortality:

“ … the decade from 1998 to 2008 has experienced a stagnation of efforts for MH. It seems that the cause of maternal mortality has not been seriously considered by decision-makers … .” (National reproductive and maternal health expert)

Key informants representing different groups of stakeholders reported that policy-makers have recognised MH as a national priority. The commitment to MH by political leaders has resulted in its prioritisation on policy agendas:

“ … the period between 2008 and 2012 saw a historical step on health system reforms, which made possible a reduction in maternal mortality. These reforms included the development of a coherent and relevant strategy, substantial funding of MH programmes and rigorous monitoring and accountability measures … .” (MOH official)

Respondents across community and technical expert networks acknowledged that maternal mortality was negatively affected by weak political commitment, which, in turn, was dependent on how decision-makers understand the problem and its social impact. As stated by the head of a NGO,

“ … stakeholders must understand that maternal mortality is a public health problem and that the consequences of maternal death are much more dramatic than policy-makers can imagine, particularly for children … Maternal death not only results in the loss of a wife and mother, but the loss of a woman and a person with a socio-economic development potential.” (Civil society representative)

In one stakeholder’s view, increased political commitment, especially by political leaders, can influence a government’s MH strategy:

“ … Overall, MH was prioritised in Morocco at an early stage, specifically at the Nairobi Conference. However, the actions taken by political decision-makers for enhancing MH evolved in a different manner. Some policy-makers have placed MH at the centre of their strategy, others have approached it timidly or stagnantly … .” (National reproductive and maternal health expert)

The process of setting MH as a priority was very sensitive to political and financial commitments. As a percentage of GDP, total expenditures on health decreased from 6.2% in 2010 to 5.8% in 2013,11 with households contributing 50.7% of these expenditures in 2013.11 Decision-making on MH should be based on approaches that reduce household expenditures, while expanding patient rights and gender equality. This can ensure the sustainability of political commitment and progress in providing adequate and quality health services on the national level that meet the needs of the population and reduce direct out-of-pocket health expenditures by households.

Political contexts provide opportunities to formulate policy

There was consensus among the respondents about the political environment in Morocco. Health policy reforms were consolidated by the adoption of the 2011 Constitution which emphasises the notion of fundamental rights and stresses the mobilisation of all available means to facilitate rights and equitable access of all populations, particularly women, to healthcare services. In addition, His Majesty King Mohammed VI has advocated the improvement and extension of UHC as a pillar of human and social development:

“ … it is also important to extend social protection and health insurance, to fight against poverty and all forms of exclusion, to strengthen social solidarity between generations by taking urgent measures to save the pension systems before it’s too late … .” (Speech from the Throne by King Mohammed VI on 30 July, 2004)

Following the High Royal Directions relating to the health sector contained in the last Speeches from the Throne and the opening of Parliament, two schemes of basic health coverage, along with an advanced regionalisation policy, were formulated in 2002:

“ … There is the king’s messages, there is a will from the highest political authority in the country. This was followed by a commitment in the government declaration, which included Universal Health Coverage, as an axis of government policy … .” (MOH official)

Respondents acknowledged an approach adopted by the MOH to develop a free maternal health policy before the generalisation of medical health insurance:

“In Morocco, several measures have been taken to reduce the financial barriers to accessing SRH. Care and health services offered at the Primary Health Care level are free. In addition, births, caesarean sections and systematic biological check-ups during pregnancy are free, and women’s general access to health care has been improved.” (MOH official)

A majority of respondents stated that the priority of UHC in the context of MH service coverage was to provide adequate and quality healthcare services to the public. There were differences, however, about how this would be achieved in Morocco:

“ … You know there are two medical cover schemes regulated through the law 65.00. The UHC plan currently covers about 68% of the population. The remaining 31% of individuals are covered by health insurance for the self-employed, either formally or informally, which represents 31% of the total population. Nevertheless, healthcare systems should be able to provide health services with sufficient resources and quality of care to the entire population … .” (Health insurance official)

In discussing the regionalisation of the health sector, policy decision-makers mentioned that MH strategies were aligned with decentralisation and regionalisation strategies. In fact, the MOH has emphasised the importance of “strengthening the management and governance of the maternal and neonatal national health strategy 2017–2021 at the regional level”.30 Each of the 12 regions of Morocco developed its own annual action plan, enabling response to regional specificities and priorities. To strengthen this dimension, the Minister of Health in 2017 established regional task forces and steering committees that aim to ensure the implementation of regional action plans to eliminate preventable deaths of mothers, newborns and children. The maternal and child health regional (district) task force is a mechanism to understand the importance of the regionalisation process. One goal is to initiate sub-national meetings focused on eliminating preventable maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity. For this purpose, a representative of the MOH noted that:

“ … following the implementation of a national strategy to eliminate maternal and neonatal mortality, the regions were asked to reflect on the formulation of regional action plans that meet the specificities of each region. Each region has a consultative committee (taskforce) made up of various stakeholders in maternal and child health programmes. These meetings provide opportunities to participate in planning and proposing corrective measures … .” (MOH official)

Thus, certain respondents mentioned the integration of the gender equality approach into public sector policy. The MOH, within the framework of the 2020 finance law, has proposed a health system performance project, which includes a reproductive health programme designed to integrate SRH within UHC. As described by a representative of the MOH:

“ … this adopted sectoral program was intended to ensure the promotion of MH and RH services … . Analysis of action plans and achievements from a gender perspective resulted in the launch in 2019 of a gender audit for the entire health department, which was designed to update the conclusions and recommendations of the audit performed in 2013 … .” (MOH official)

All respondents recognised that the political context was very favourable, with policy “windows” that offered an environment conducive to women’s needs and rights, and gender equality. However, women may lack equal access to health services, with gaps still existing between institutional statements and policies and their implementation.5,6,31

Maternal health characteristics

Most interviewees and stakeholders agreed on the basic definitions of MH and recognised MH as being crucial to achieve national health outcomes:

“ … for years maternal mortality rates were a source of national concern as they were too high. This put Morocco in an international situation that did not correspond to the socio-economic development of the country … .” (National technical expert)

Stakeholders generally believed that the MOH has made progress in monitoring results and tracking resources. Periodic national population and family demographic and health surveys since the 1980s have enabled the Ministry to monitor the development of MH indicators.

“ … Many departments have focused on a core set of health indicators as part of the national plan. Progress has been reported and reviewed on an annual basis. MH performance is determined by monitoring routine data, as well as data from the Demographic Health Surveys … .” (MOH official)

In addition, the causes and circumstances of maternal deaths are well documented through the Maternal Death Surveillance System (MDSS).17,32 The MDSS was implemented in 2009 and has included clinical audits at the hospital level and verbal autopsies at community levels. In line with this, our interviews revealed that, based on three MDSS reports:

“ … Maternal deaths are identified and reviewed through confidential audits in health facilities and verbal autopsies in communities throughout the entire country. This system has enabled better understanding of the causes and circumstances of maternal deaths, as well as providing a basis for action. This system is currently being revised to integrate the audit of neonatal deaths and stillbirths, and to strengthen responses.” (MOH official)

The Three Delays Model has identified three groups of factors that can improve access of women and girls to the MH care they require. Respondents across policy networks acknowledged the national efforts to improve the process of population targeting, especially to reduce any initial delay by utilising community health workers (CHWs) to perform many community interventions, including obstetric emergency services in rural areas and “Dar Omouma”, a “waiting house” in which isolated rural women who do not have access to obstetrics services stay to be observed before and after birth:33,34

“ … Maternal mortality and morbidity is a consequence of gender inequality, discrimination, and a failure to guarantee women’s human rights, especially women in rural areas … . Thus, we believe that a community intervention like Dar Omouma, which provides women the opportunity to be near skilled attendants, should be applied throughout the country. In addition, we are concerned about the sustainability of the engagement of community health workers … .” (Civil society representative)

Maternal health prioritisation outcomes

Stakeholders considered that the health reforms instituted in recent decades represent political achievements. Several measures have been taken to reduce maternal mortality rates and improve access to quality maternal care.

“ … From my point of view, many factors have contributed to success. These factors can be grouped into three categories: strategies based on scientific evidence, action plans developed in a participatory way, and regular and proximity monitoring … .” (MOH official)

In Morocco, healthcare services offered at the PHC level are free of charge. In addition, the free births policy has improved women’s general access to MH care. The MOH devotes 28% of this expenditure to PHC facilities, excluding staff and buildings, which increased 110% from 2001 to 2018.2 As mentioned by an interviewee from the financial resources department of the MOH:

“ … the free delivery policy was evaluated and it had a positive impact on improving the rate of skilled birth attendants … Currently, the basic medical coverage (BMC) system in Morocco is the model chosen to achieve the goal of UHC … Morocco reaffirmed its commitment to the global compact of the UHC until 2030, as well as signing the declaration on Universal Health Coverage in Salaalah, Oman, in September 2018 … .” (MOH official)

Most of the information and communication technologies (ICT) used currently in Morocco are pilot activities and have not yet been expanded. eHealth strategies have been instituted in Morocco, and web-based health facility reporting systems are now being expanded nationally. As stated by an official at the MOH:

“Health information is not computerised, so the challenge today is to computerise the hospital networks and the network of PHC facilities and to link these two networks. This task is currently in progress.” (MOH official)

Respondents across policy networks acknowledged the efforts established to improve governance arrangements to improve performance, accountability, responsiveness and participation, including efforts to raise awareness and create positive behavioural changes. In addition to these actions, Morocco has developed a Commission on Information and Accountability for Women’s and Children’s Health (CoIA) roadmaps with WHO support and agreed on the accountability mechanisms.

“ … The accountability roadmap came as a response to the accelerated maternal and child health care plan developed in accordance with the Dubai Declaration in 2013 … .” (UN Agency)

The MOH is still working on strengthening accountability tools and mechanisms to reach MH/SDG targets by 2030. Likewise, a national survey of the quality of health services offered to mothers and newborns at hospitals identified several shortcomings, finding that the equipment and conditions for childbirth were inadequate in most facilities.35

To respond to the recommendations of the WHO and to consolidate the achievements in maternal and newborn care (MNC), it is necessary to identify measures of improvement of quality of care affecting organisational, managerial and management aspects. These can ensure the provision of accessible, available, comprehensive MNC:35

“ … In December 2018, we presented the main results of the national assessment of maternal and newborn quality of care using colour coding in green (good), orange (mediocre) and red (poor). Responses were not always green. I remember that there was less green, more orange and a little red. I remember the minister said that there was more orange … Therefore, there was a need to address this situation by instituting improvement plans in each hospital … .” (MOH official)

Discussion

Setting healthcare priorities in a setting of limited resources is not always easy, and reporting and documentation are often lacking.23 This case study of MH prioritisation in Morocco, including documented findings and a review of unpublished reports, found that prioritising MH was crucial for building a resilient healthcare system and adopting a cost-effective and equity based MH coverage.23

Both the reviewed documents and the interviews reported that there was a strong political commitment to MH in Morocco, especially in relationship to achieving Millennium Development Goal 5.12,13 This study found that a range of criteria, not all health-specific, were utilised to set priorities for MH, indicating that this involves multiple criteria beyond cost-effectiveness and its impact on MH. Rather, prioritisation of MH and the achievement of UHC requires addressing underlying social determinants, such as poverty, illiteracy, unemployment and marginalisation.23,27

With regard to the component of the framework relating to the influence of individuals participating in setting priorities, actors and stakeholders involved in the implementation of MH prioritisation contributed to various debates on the issue. In general, these actors, who come from diverse and heterogeneous networks involved in improving SRH, are useful in harmonising the collective understanding of this problem, its solutions and its prioritisation.36 However, this diversity can have a negative influence on cohesion and agreement on key priorities.37 The present study found that, in addition to the collective recognition of deficiencies in maternal healthcare services, these actors were in agreement on funding needs, supported by resources available within UHC. In addition to being supported by partners in MH programmes and projects that fit their agendas and vision, this convergence in decision-making ability often leads to high political commitment in Morocco.

Assessing the role of context in designing MH priorities in Morocco, the study found that the context was not simple and was highly influenced by political and economic challenges as well as the engagement of a broad range of partners and stakeholders belonging to different backgrounds. This result allies with an extensive 2012 review of national-level priority-setting for health service packages and health technologies in low- and middle-income countries.28 The social development context in Morocco was led by a high level of political commitment, especially the 2011 constitution that stressed rights to equity and equal access to healthcare services for all citizens, followed by the advanced regionalisation process in Morocco and gender equality policy, all of which greatly influenced the priority-setting process of MH/SRH within the HBP. Thus, the respect, protection and fulfilment of the human rights of girls and women are accompanied by significant advances in the health system to meet their health needs.38 Although Morocco has shown progress in economic growth, political stability and social solidarity, the problem of inequalities between men and women, rich and poor, rural and urban regions, and developed and less developed locations, remains a challenge for Moroccan policy-makers.25,39

The interviews also demonstrated that the financial and economic contexts during prioritisation processes were complex, as it was challenging to advocate for the benefits of universal MH coverage along with financial protection of all women. Several approaches can influence policy-makers in making budgetary changes based on costs and benefits.29 These approaches require clear, reproducible methods along with a structured involvement of stakeholders. In Morocco, the funding changes made to prioritise MH within the HBP were due primarily to high political involvement convictions on health policy, more than to adopting institutionalised approaches based on costs and benefits. However, there are several challenges to this dynamic. For example, the funding generated by mandatory health insurance is de facto, as it is dependent on the choices made by covered individuals and is captured mainly by the private care sector. In addition, public institutions pay most healthcare costs for the poorest individuals, and difficulties arise in attempting to control the overall performance of the system.40

Our interviews confirmed that MH data and information systems have a considerable effect on the prioritisation of MH within the HBP. These data help attract political attention and involve politicians in an evidence-based process of prioritisation. Measurements are essential in analysing the causative factors and determinants of MH issues and in designing a healthcare system that can provide better universal MH coverage.

This study found that the formulation of maternal care services is influenced by several factors. These include the influence of actors and leaders, including the MOH leadership, as well as other government ministries, including the Ministry of the Interior, and the Ministry of Solidarity, Social Development, Equality and the Family. Also involved are the cohesion of the various stakeholders, who should be involved in developing a joint action plan, the availability of resources and the setting of requirements for prioritisation of MH within UHC. In addition, the political will of development partners and powerful national bodies is critical for securing committed action on an issue.38,41

The results of this study have contributed to our understanding of the complexities associated with political setting of healthcare agendas in Morocco. Despite MH being a national healthcare priority, with a supportive socio-economic and political environment, the maternal mortality rate remains high. Further strengthening of the health care delivery system, especially quality of care, and ensuring equitable access to MH services through adequate availability of human resources, equipment and infrastructure are needed.

Limitations

This case study had several limitations, including in its theoretical framework and data collection process. The Shiffman and Smith framework does not evaluate the implementation of a policy following its enactment. Rather, it can highlight the components of problem analysis that can be used to raise the profile of a condition to an actionable problem.

There were also difficulties controlling as yet unidentified confounding variables that may have influenced our results and of estimating the weight of factors identified as crucial in the prioritisation of MH policy. To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore such a complex issue of whether or not to prioritise a healthcare problem.

Further research comparing prioritised initiatives that vary in levels of political support is required to identify factors that influence the setting of political priorities.

Health policy implications and programmes

Although efforts have been made to establish MH regulations, more direct actions are needed to ensure the implementation of maternal healthcare services that improve quality of care. By exploring different factors influencing MH services in Morocco, this study revealed that adopting a women-centred approach as well as expanding the healthcare services and resources are key to delivering MH. Policy-makers did not systematically adopt human rights and gender-based principles or consult concerned stakeholders while developing programmes. Gaps were observed between setting policy and programme development and implementation. Therefore, it is important to ensure agreement among actors, including the adoption of bottom-up approaches, so that policies match the actual needs of the target populations. Translating MH regulations into actual programmes requires defined human and financial resources, equitable MH coverage and a quality of care that responds to the needs, rights and dignity of women.

Conclusion

Prioritisation of MH within a sexual and reproductive health benefits package (SRHBP) is crucial to achieve UHC by the year 2030. Addressing inequalities that affect SRH and gender equality, and preventing avoidable maternal deaths are fundamental to ensure better coverage of high-quality maternity care services. Prioritising MH services within an SRH package is dependent on leadership, the engagement and commitment of policy-makers, and the willingness of relevant actors to advocate a policy of MH. This case study in Morocco has shown that the coordinated involvement of governmental, civil society and non-governmental organisations were key to prioritising maternal health within the SRHBP.

Acknowledgements

This study was initiated and fully funded by the WHO Geneva. The authors would like to acknowledge deeply the technical support and guidance of the WHO-EMRO team, including Dr Karima Gholbzouri, Medical officer of reproductive and maternal health, WHO Geneva; and Veloshnee Govender, Georges Danhoundo, and Asmae Alami Fellouss; and the sociologist Ababou Mohammed. The authors would also like to thank all key interviewees and other participants for their support during this study. BA, SE and RB made substantial contributions to the conception and the design of the study. BA coordinated the data collection, and SE and RB were involved in the interviews and focus groups. BA and SE analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RB assisted in interpreting the results. All authors participated in the revision of the manuscript, and have read and approved the final version for submission.

Appendix. Moroccan case study: analysis of the prioritisation of maternal health (MH) under conditions of universal health coverage (UHC).

Extraction sheet of disk review

The preliminary findings will include the following descriptive analyses using tables and figures, where appropriate, to describe:

Progress of the UHC in Morocco with a focus on MH;

Individuals and organisations involved in the design, prioritisation and implementation of the UHC with a focus on MH;

The historical, political, socio-economic and cultural factors that influenced Morocco’s progress towards UHC with a focus on MH;

Description of current systems, structures (gender norms and legal barriers) and processes in place that support the inclusion of MH services in UHC;

Existing MH services in Morocco, their organisation, the type of coverage proposed, their funding, and the roles of the State and the private sector in funding and provision;

Factors, including historical, political, socio-economic and cultural factors, that have affected population coverage, coverage of services and protection against financial risks for a full range of SRH services;

Health status and access to MH benefits by gender, residency and income level;

Measures taken by Morocco to progress towards universal coverage of MH and its current state of their implementation;

Description of decision-making processes and accountability mechanisms in the design and implementation of MH services in UHC;

Description of civil society and community organisations involved in the design, prioritisation and implementation of MH services in UHC;

Conclusion and recommendations: context-specific lessons learned; successes and recommendations for strengthening health systems and participatory processes in the context of MH services in UHC.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the World Health Organization in Geneva.

References

- 1.Ministère de la santé du Maroc . Stratégie Nationale de la Santé de la Reproduction 2011–2020; 2011.

- 2.Ministère de la santé du Maroc . Plan Sante 2025; 2018.

- 3.Dahir . n° 1-11-83 du 2 juillet 2011 portant promulgation de la loi cadre n° 34-09 relative au système de santé et à l’offre de soins [Internet]. Bulletin Officiel N 5962 du 21-07-2011; 2011. [cited 2020 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.sante.gov.ma/Reglementation/Pages/SYSTEME-DE-SANTE-ET-OFFRE-DE-SOINS.aspx

- 4.du Maroc R. Ministère de la Santé. Enquete nationale sur la population et la sante familiale; 2018.

- 5.du Maroc R. Rapport National sur Population et Développement 25 ans après la conférence du Caire 1994; 2019.

- 6.du Maroc R. Rapport national 2020. Examen national volontaire de la mise en œuvre des Objectifs de Développement Durable; 2020.

- 7.Gruénais M-É. La publicisation du débat sur l’avortement au Maroc. L’État marocain en action. L’Année du Maghreb. 2017;17:219–234. [Google Scholar]

- 8.du Maroc R. Enquête nationale sur la prévalence de la violence à l ‘ égard des femmes au Maroc; 2009.

- 9.Zaouaq K. Les femmes et l’accès aux soins de santé reproductive au Maroc. L’Année du Maghreb. 2017;17:169–183. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhnif EH, Hachri H, Belmadani A, et al. Policy dialogue and participation: a new way of crafting a national health financing strategy in Morocco. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2020 Dec 29;18(1):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministère de la santé du Maroc . Comptes Nationaux de la Santé; 2015.

- 12.Ministère de la santé . Stratégie sectorielle de Santé 2012–2016. Ministère de santé; 2012. 103 p.

- 13.du Maroc R. Ministère de la Santé. Plan d’action santé, 2008–2012 « Réconcilier le citoyen avec son système de santé »; 2008.

- 14.Ministère de la santé . Plan d’action pour acceler la reduction de la mortalite maternelle et neonatale. Fin du Compte à rebours 2015. Action; 2012.

- 15.United Nations Development Programme . Human development report 2019. Inequalities in human development in the 21st century morocco introduction; 2019.

- 16.Ministère de la Santé . Carte sanitaire; 2019.

- 17.Ministère de la Santé du Maroc . Enquête confidentielle sur les décès maternels de 2015 dans les six régions prioritaires au Maroc; 2015.

- 18.Freedman LP. Using human rights in maternal mortality programmes: from analysis to strategy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2001;75(1):51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.du Maroc R. Secrétariat Général de Gouvernement. la constitution. Edition 2011.

- 20.Shiffman J, Smith S.. Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. The Lancet. 2007;370:1370–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walt G, Gilson L.. Can frameworks inform knowledge about health policy processes? Reviewing health policy papers on agenda setting and testing them against a specific priority-setting framework. Health Policy Plan. 2014 Dec 1;29(suppl_3):6–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016;2:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norheim OF, Baltussen R, Johri M, et al. Guidance on priority setting in health care (GPS-health): the inclusion of equity criteria not captured by cost-effectiveness analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2014 Aug 29;12(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.L G EE. How to start thinking about investigating power in the organizational settings of policy implementation. Health Policy Plan. 2008 Sep;23(5):361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boutayeb A. Social determinants and health equity in Morocco. WHO. World Conference on Social Determinants of Health; 2011. Oct 19–21; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Initiative Nationale pour le Développement Humain – Accueil [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 26]. Available from: http://www.indh.ma/en/

- 27.Baltussen R, Jansen MP, Mikkelsen E, et al. Priority setting for universal health coverage: we need evidence-informed deliberative processes, not just more evidence on cost-effectiveness. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5:615–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ministère de la Santé . Mise en œuvre de la déclaration politique sur le VIH/Sida. Rapport national 2014; 2014.

- 29.CCM – Comité de Coordination Maroc [Internet] . [cited 2020 Sep 26]. Available from: http://ccm.tanmia.ma/

- 30.du Maroc R, de la Santé M. Stratégie d’élimination des décès évitables des mères et des nouveau-nés 2017–2021. “toute mère tout nouveau-né compte.” 2017.

- 31.Zaouaq K. Les femmes et l’accès aux soins de santé reproductive au Maroc. L’Année du Maghreb. 2017 Nov 13;17:169–183. Available from: http://journals.openedition.org/anneemaghreb [Google Scholar]

- 32.du Maroc R. Ministère de la Santé. l’enquête confidentielle sur les décès maternels au Maroc. Deuxième rapport du Comité National d’Experts sur l’Audit Confidentiel des Décès Maternels; 2013.

- 33.UNICEF . Dar al Oumouma.La naissance du changement [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/morocco/recits/dar-al-oumouma

- 34.UNICEF . Les foyers maternels au Maroc: Donner la vie en toute sécurité; 2008.

- 35.Ministère de la Santé du Maroc . Rapport de l’enquête nationale d’évaluation de la qualité des soins et des services des maternités hospitalières et des unités de néonatologie au niveau des hôpitaux régionaux au maroc; 2018.

- 36.Quissell K, Walt G.. The challenge of sustaining effectiveness over time: the case of the global network to stop tuberculosis. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(Suppl 1):17–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith SL, Rodriguez MA.. Agenda setting for maternal survival: the power of global health networks and norms. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31:i48–i59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sen G, Govender V.. Sexual and reproductive health and rights in changing health systems. Glob Public Health. 2015 Feb 7;10(2):228–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Observatory of Human Development . Evaluation of progress towards inclusion. 2nd annual ONDH report, May; 2011.

- 40.Akhnif EH. La Couverture Sanitaire Universlle au Maroc : Le rôle du ministère de la santé en tant qu’Organisation Apprenante. Vol. 53. UCLouvain; 2019.

- 41.Jat TR, Deo PR, Goicolea I, et al. The emergence of maternal health as a political priority in Madhya Pradesh, India: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013 Sep 30;13(1):181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]