Abstract

Fifty-two maternal deaths occurred between September 2017 and August 2018 in the Rohingya refugee camps in Ukhia and Teknaf Upazilas, Cox’s Bazar District, Bangladesh. Behind every one of these lives lost is a complex narrative of historical, social, and political forces, which provide an important context for reproductive health programming in Rohingya camps. Rohingya women and girls have experienced human rights violations in Myanmar for decades, including government-sponsored sexual violence and population control efforts. An extension of nationalist, anti-Rohingya policies, the attacks of 2017 resulted in the rape and murder of an unknown number of women. The socio-cultural context among Rohingya and Bangladeshi host communities limits provision of reproductive health services in the refugee camps, as does a lack of legal status and continued restrictions on movement. In this review, the historical, political, and social contexts have been overlaid below on the Three Delays Model, a conceptual framework used to understand the determinants of maternal mortality. Attempts to improve maternal mortality among Rohingya women and girls in the refugee camps in Bangladesh should take into account these complex historical, social and political factors in order to reduce maternal mortality.

Keywords: Rohingya, Myanmar, maternal mortality, abortion, Bangladesh

Résumé

Cinquante-deux décès maternels se sont produits entre septembre 2017 et août 2018 dans les camps de réfugiés rohingyas dans les upazilas d’Ukhia et de Teknaf, district de Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Derrière chacune de ces vies perdues se cache un ensemble complexe de forces politiques, sociales et historiques qui constitue un contexte important pour la définition des programmes de santé reproductive dans les camps de Rohingyas. Pendant des décennies, les femmes et les filles rohingyas ont subi des violations de leurs droits humains, notamment des violences sexuelles encouragées par les autorités et des activités de contrôle des naissances. Dans le prolongement des politiques nationalistes anti-Rohingyas, les attaques de 2017 ont abouti au viol et au meurtre d’un nombre inconnu de femmes. Le contexte socioculturel parmi les Rohingyas et les communautés hôtes bangladeshies limite la prestation de services de santé reproductive dans les camps de réfugiés, tout comme le manque de statut juridique et le maintien des restrictions sur les déplacements. Dans cette analyse, les contextes historiques, politiques et sociaux ont été superposés sur le modèle dit des “ trois retards ”, un cadre conceptuel utilisé pour comprendre les déterminants de la mortalité maternelle. Les mesures prises pour améliorer la santé maternelle des femmes et des filles rohingyas dans les camps de réfugiés au Bangladesh devraient tenir compte de ces facteurs historiques, sociaux et politiques complexes afin de réduire la mortalité maternelle.

Resumen

Entre septiembre de 2017 y agosto de 2018 ocurrieron 52 muertes maternas en los campos de refugiados rohingyas, en Ukhia y Teknaf Upazilas, en el Distrito de Cox's Bazar, en Bangladesh. Detrás de cada una de estas vidas perdidas hay una compleja narrativa de fuerzas históricas, sociales y políticas, que proporcionan un importante contexto para los programas de salud reproductiva en los campos rohingyas. En Myanmar, las mujeres y niñas rohingyas llevan décadas sufriendo violaciones de sus derechos humanos, tales como violencia sexual y esfuerzos de control de la población auspiciados por el gobierno. Los ataques de 2017, una extensión de políticas nacionalistas anti-rohingyas, comprendieron la violación y el asesinato de un número desconocido de mujeres. El contexto sociocultural entre rohingyas y comunidades de acogida en Bangladesh así como la falta de estatus legal y continuas restricciones de movimiento limitan la prestación de servicios de salud reproductiva en los campos de refugiados. En esta revisión, los contextos históricos, políticos y sociales se han superpuesto a continuación en el Modelo de Tres Demoras, marco conceptual utilizado para entender los determinantes de la mortalidad materna. Los intentos por mejorar la mortalidad materna entre las mujeres y niñas rohingyas en los campos de refugiados en Bangladesh deben tomar en cuenta estos complejos factores históricos, sociales y políticos, con el fin de reducir la mortalidad materna.

Introduction

In 2015, 61% of 303,000 global maternal deaths occurred in fragile and conflict-affected states.1 Many women affected by conflict face not only the sequelae of violence and displacement, but also sexual violence, unwanted pregnancy, and poor access to reproductive health care. While evidence-based interventions such as the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) can reduce maternal mortality among refugees, its implementation can be hampered by complex refugee and host country factors.2

Following widespread, coordinated attacks in Rakhine State, Myanmar, 700,000 Rohingya were forced to migrate to Bangladesh in 2017.3 The current crisis has deep historical roots. The Rohingya differ in language, appearance, and religion from Myanmar's dominant Buddhist group, the Bamar.4 The Myanmar government has systematically deprived the Rohingya of basic rights for decades, imposing limitations on the right to marry, bear children, vote or participate in civic life, obtain education, freely travel, and access justice mechanisms.4–8 The UN Fact Finding Mission on Myanmar conducted an investigation into these attacks, and called for prosecution of senior Myanmar military leaders for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.9

Women and girls represented 52% of the over 900,000 Rohingya refugees living in refugee camps in Bangladesh.10 Between September 2017 and August 2018, 52 maternal deaths out of 82 pregnancy-related deaths occurred within these camps.11 This review article aims to explore the historical, social, and political contexts of maternal mortality among Rohingya refugees via the lens of the Three Delays Model, which is discussed in greater detail below.

Reproductive health services in Rohingya refugee camps of Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh

As of January 2019, there were an estimated 646,000 women and girls living in the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, including 22,000 pregnant women.12 To meet their reproductive health needs, the MISP has been implemented, with United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) serving as the lead agency.13 The five objectives of the MISP are: to ensure full implementation of the MISP itself, to prevent and manage the consequences of sexual violence, to reduce transmission of HIV, to prevent maternal and neonatal mortality and to plan for integration of comprehensive reproductive health care into primary care settings. Maternal mortality is prevented by making emergency obstetric care available, establishing a 24 h per day, seven days per week (24/7) referral system, by providing clean delivery kits to skilled birth attendants and visibly pregnant women, and ensuring the community is aware of services.13

Multiple constraints limit women's access to reproductive health services, including facility-based births. In general, cost serves as a barrier for all Rohingya refugees seeking health care. According to a 2017 Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) survey, 42% of those unable to access care in the camps cited cost as the primary barrier.14 While the 11 Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (BEmONC) (Table 1) facilities for a population of roughly 900,000 meet the Sphere standard of five such facilities per 500,000 people, crowded camps, a lack of roads, and challenging terrain make these facilities difficult to access for many refugees.15–17

Table 1. Basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care services*.

| Basic services |

|---|

| 1) Administer parenteral antibiotics |

| 2) Administer uterotonic drugs (i.e. parenteral oxytocin) |

| 3) Administer parenteral anticonvulsants for eclampsia and pre-eclampsia (i.e. magnesium sulfate) |

| 4) Manually remove the placenta |

| 5) Remove retained products (e.g. manual vacuum extraction, dilation and curettage) |

| 6) Perform assisted vaginal delivery (e.g. vacuum extraction, forceps delivery) |

| 7) Perform basic neonatal resuscitation (e.g., using bag-valve mask) |

| Comprehensive services |

| 8) Perform surgery (e.g. cesarean section) |

| 9) Perform blood transfusion |

*A basic emergency care facility performs 1–7. A comprehensive emergency care facility performs 1–9. Adapted from: Monitoring Emergency Obstetric Care, a handbook.22

The Sphere standards, which provide minimum standards and indicators for use in humanitarian crises, suggest that one facility offering Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (CEmONC) (Table 1) should be present for every 500,000 persons.17 Hospitals offering cesarean deliveries and blood transfusions near the camps include the Friendship Hospital, Turkish Field Hospital and Malaysian Field Hospital. These are located on the main road just outside the Kutapalong megacamp. Also providing cesarean deliveries is Ukhia Health Complex, (a Government of Bangladesh Facility located 10 min from the Kutapalong megacamp), the Cox's Bazar District Hospital (a government facility), and the Hope Ramu Hospital in Cox's Bazar. Hospitals in Cox's Bazar are roughly 2.5 hours away by motor vehicle.18

While there is one facility offering CEmONC inside the camp, it is not open 24/7.18 Women often have to go through multiple steps to access adequate care, first arriving at a clinic, then finding an ambulance, then arriving at a hospital. Multiple referrals are the norm, sometimes resulting in hours of delay before a woman arrives at a facility capable of managing an obstetric complication.19 Currently, no standardised emergency transport protocols exist in the refugee camps. Challenges with availability of supplies and appropriate medical staff have been noted in some facilities, limiting provision of care when women arrive at health facilities.20 Anecdotes of challenges with supplies and availability of medical staff exist, likely exacerbated in part by a nearly US$ 4 million shortfall in humanitarian funding for reproductive health services.21

The Three Delays Model

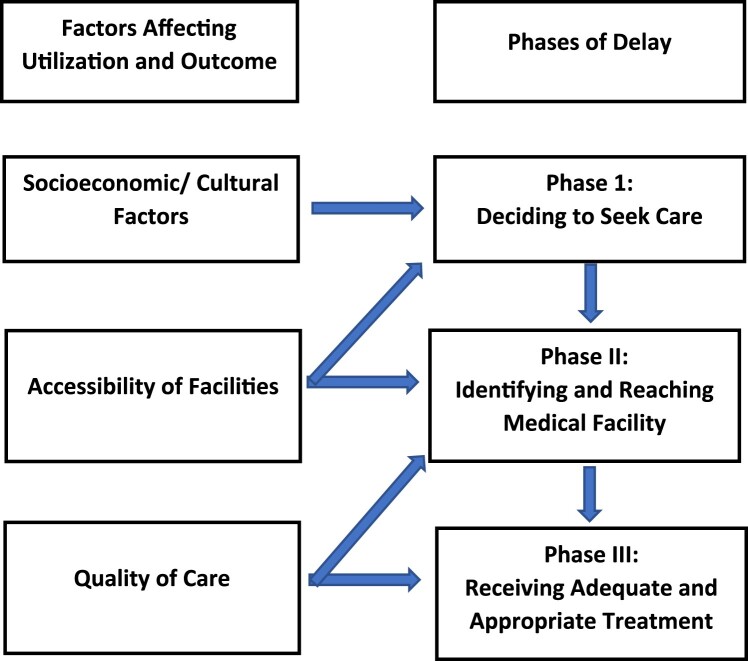

The Three Delays Model is a conceptual framework used to understand the determinants of maternal mortality.23 According to this model, the first delay is in the decision to seek care; the second delay is in reaching a health facility; the third delay is in receiving appropriate care once at the facility. Each delay is followed by discussion of the broader contextual factors that contribute, and what interventions might be needed.

According to Thaddeus et al (see Figure 1), examples of factors that affect a delay in seeking care, or the first delay, include women's decision-making powers, women's societal status, opportunity and financial costs, perceived severity of illness, distance to facilities, previous experience with the health care system and perceived quality of health care. The second delay results from difficulty reaching a health facility. This may result from challenges travelling from home to a facility or resulting from the distribution of facilities themselves, physical barriers, poor availability or high cost of transportation, or poor road conditions. The third delay results from a delay in receiving adequate care at a facility. This may result from issues with regard to staff or supplies at the facility, or competencies of available personnel. Of note, these delays interact; for example, widespread knowledge of instances of the third delay, or delayed care received by women in a community may prevent women from making the decision to seek care.23

Figure 1.

Three Delays Model23

The first delay

The first delay contributes to the vast majority of maternal mortality in Rohingya refugee camps, and thus will receive the greatest attention below.

Fear contributing to the first delay

Rohingya refugees’ willingness to seek reproductive health care in Bangladesh is affected by previous negative experiences with repressive policies and reproductive health care in Myanmar.24 Rohingya women and girls have been uniquely impacted by human rights violations in Myanmar, including sexual violence and government-sponsored population control efforts. Rohingya couples are legally required to obtain permission from government authorities prior to marrying in Myanmar, a restriction that is not applied to any other ethnic minority.4 Myanmar has also imposed a two-child only policy on Rohingya women, with leaked government documents encouraging authorities to force women to use birth control.4,25 This policy was implemented to combat the perceived threat of a growing Muslim population, despite evidence that the Rohingya population is stable or has declined when compared to other minorities.12 The leaked government policy referenced above also suggested that women be forced to breastfeed children in front of military personnel during two-child policy “spot checks,” to prove their relationship.4 Furthermore, Myanmar implemented a law requiring women to space births by 36 months and prohibiting religious conversion and interreligious marriage.26 The international community largely perceived these laws as targeting the Rohingya minority.27

Repressive nationalist policies in Myanmar have had direct consequences for the reproductive health of Rohingya women. Some researchers believe women have induced abortion in order to comply with the two-child policy, with an estimated one out of every seven Rohingya women reporting history of abortion.28 Access to abortion is highly restricted in Myanmar for all women, available only in cases when the mother's life is endangered; thus, many women resort to unsafe methods, such as inserting a stick into the uterus.4,29,30 Maternal mortality among Rohingya was estimated to be 400 per 100,000 live births in 2013, double that of other citizens in Myanmar (200 per 100,000 live births).29 Aid groups report this difference in mortality is driven significantly by the two-child policy, illegal abortion, and restricted access to health care.29

Pervasive discrimination by health providers against Rohingya living inside Rakhine State has been documented, including provision of limited numbers of segregated hospital beds, denial of medical care, extortion via higher fees and bribes, and physical abuse.31 According to Amnesty International, women have reported delaying seeking medical care while pregnant, due to fear.31 Once a woman chooses to seek care, a large proportion of health facilities are inaccessible as a result of travel restrictions and the expense of paying bribes to access services.4 There are also multiple reports of women dying as a result of obstructed labor due to delays imposed by travel restrictions inside Rakhine state.28 As Rohingya individuals have been largely excluded from national statistics, many Rohingya women have likely died in their homes, uncounted.32,33

The attacks which began in August of 2017 directly targeted Rohingya women and girls. Military troops have raped Rohingya women and girls in Rakhine State with impunity for decades, with surges in violence occurring in 2016 and most recently in August of 2017.34–36 These assaults often involved multiple perpetrators and involved beatings, burning, or other torture that left women maimed and/or dead.34,37 Women in Tula Tuli hamlet reported rape by multiple uniformed military who then locked raped women in homes and set these homes on fire; those who escaped had burns on their hands and feet from crawling out of the homes.37 It is unclear exactly how many women and children were affected, as women are reluctant to report experiences with sexual violence, particularly in this conservative context.38,39 These widespread and systematic rapes also resulted in an unknown number of pregnancies, possibly thousands, according to aid actors in Bangladesh.40 Emergency contraception, though available in the camps, could not typically be accessed in a timely fashion given the days to weeks women spent in flight.41,42

This decades-long history of discrimination, rape, and reproductive control constitutes important context when considering Rohingya women's profound reluctance to seek antenatal care and facility-based birth. As of February 2018, only 22% of all births within Rohingya refugee camps in Cox's Bazar were facility-based.43 Women most often deliver in their homes with traditional birth attendants or female family members, sometimes with facilities located minutes from their homes.19 According to an October 2018 study, some women fear facility-based birth as they are concerned their male children will be killed by the authorities or they will be prevented from implementing their ritual of reciting the “Azan” or call to prayer when a boy is born. One participant from the same study said, “We want to go to the health centers. But many do not go in fear of losing a kidney from mother and child, particularly during cesarean operation.”44 Further, reports of a Bangladeshi voluntary sterilisation programme in Rohingya refugee camps echoed the reproduction restrictions imposed in Myanmar, leading to widespread discomfort amongst Rohingya.45

Gender, social and cultural norms

The conservative culture among Rohingya and Bangladeshi host communities serves as an additional barrier for women and girls seeking to access reproductive health care. Rohingya women and girls are generally expected to stay at home and not interact with male strangers.46 “Purdah,” which translates as “curtain,” is the practice of keeping women out of the view of men other than their husbands. In Rakhine State, there is a socio-economic dimension to this practice, in that richer families can afford to keep women at home and out of the workplace, while poorer families are forced to send women to work. Thus, observing purdah is a source of pride in Rohingya culture.24 One study found that 53% of Rohingya refugee women surveyed believed that women should not leave the home, with 42% of women reporting they stayed in their homes 21–24 hours per day.35

Rohingya women prefer female health providers and are reluctant to seek health care in mixed gender facilities.24 Unfortunately, increased presence of Rohingya women in non-traditional roles in the camps, as community health workers, breadwinners, and in leadership roles, has led to increased social friction in the camps.24 Female Rohingya aid workers have been threatened and attacked in recent months by militants from the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, leading some women to abandon work supporting the refugee community, a situation that may result in reduced numbers of female Rohingya interpreters at health facilities, community health workers and health staff.47

Rohingya women report limited decision-making power and generally will not seek health care without being accompanied by a male relative or husband. Husbands and mothers-in-law primarily decide when women may use contraceptives or access reproductive services, including facility-based delivery.24,48,49 According to the Intersectoral Gender in Humanitarian Action Working Group, some older Rohingya women consider it “cowardly” to deliver under the care of allopathic health care providers in a hospital.50 Contraception, however, can be justified under Islam, as families are charged with only having children they are able to provide for.24 Socio-cultural norms also impact care-seeking behaviours with regard to pregnancies resulting from rape. In these cases, women may attempt termination at home due to a high degree of stigma in their families and communities. MSF has anecdotally reported a large number of women with resulting septic abortions and maternal haemorrhaging presenting to their facilities.41

Currently, almost all health messaging occurs in collaboration with the Majis (or Majhis), who are male, government-appointed community leaders in Rohingya refugee camps.49 Previous studies have found Majis to be complicit in rape, trafficking, protecting perpetrators of intimate partner violence and other abuses of power, making these leaders inappropriate partners in reproductive health initiatives.7,49,51 Overall, 73% of Rohingya refugees self-identify as non-literate, a number suspected to be substantially higher among women due to conservative social norms that limit women's access to education.43 Unfortunately, non-literacy and a lack of female leadership in the camps limit avenues for gender-sensitive communication with women regarding reproductive health.

Further complicating the situation, gender inequity is pervasive in the host country, Bangladesh. Gender norms in Bangladesh limit girls’ mobility after the onset of puberty, limiting access to education and livelihoods.46 Forty-eight per cent of Bangladeshi women state that their husbands make decisions about their health, and intimate partner violence is common.46 Although dramatically improved over the past decade, the maternal mortality ratio in Bangladesh remains high at 176 per 100,000 live births (2015).52 The majority (62%) of women in Bangladesh also deliver at home, placing Bangladesh in the bottom 10% of countries with regards to facility-based birth.53 A 2016 evaluation found that less than half of the sexual and reproductive health programming evaluated in Bangladesh addressed adolescent reproductive health needs, citing conservative social norms as a primary factor.32 In government clinics, family planning, pregnancy-related services and post-abortion care are not given to unmarried women.32 Humanitarian programming requires host country approval, which may create barriers in challenging conservative socio-cultural norms.

The second delay

As described above, the second delay results from barriers in reaching care once an emergency has been identified. Here, the political context for refugees in Bangladesh plays a significant role. Bangladesh has one of the world's highest population densities and limited land availability, thus limited land has been made available for the Rohingya refugee camps, resulting in crowded settlements that are difficult to navigate.54 Ambulances, which are generally sport utility vehicles or vans, cannot penetrate the majority of the camps as much of the area is inaccessible by road.19,55 Women with obstetric emergencies often have to walk or be carried out on makeshift stretchers (bamboo poles balancing a chair or cloth) from their homes on hilly, sometimes muddy and slippery terrain. As a result, women with obstetric emergencies often stay home for days, resulting in death from haemorrhage, sepsis, and complications of obstructed labor.56 As mentioned above, while the number of BEmONC facilities available in the camps meets standards, crowded camps, a lack of roads, and challenging terrain make these facilities difficult to access for refugees on the periphery of the camps.15–17

Rohingya women have limited mobility outside of the camps due to a lack of legal status as refugees in Bangladesh. While Bangladesh has gone to great lengths to support the Rohingya after the most recent crisis, it is not a signatory to the 1951 Convention on Refugees.57 Rohingya are classified as Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals, or FDMNs.58 As such, FDMNs do not have the rights of refugees and are not allowed to move freely outside the camps. Checkpoints have been cited as the most common restriction on movement among refugees, though with a medical pass this can be overcome, allowing women restricted access to CEmONC facilities outside the camps.59 Prior to the current crisis, a checkpoint was responsible for at least one neonatal death.60 It is unclear how checkpoints, still in effect, delay transport to facilities outside the camps.

The third delay

The third delay is in receiving appropriate care once at the facility. A broad overview of the type of clinical care provided against the UNFPA standards (Figure 1) is provided above, indicating that essential services are available for life-saving obstetric care, although our review does not aim to elicit clinical quality in depth.22 Here, we highlight how other factors such as government policies and discrimination against Rohingya people may impact the quality of services received by pregnant women, illustrating the interconnectivity between the first and third delays.

Employment of Rohingya refugees is restricted, which serves as a barrier to implementation of services that are linguistically and culturally appropriate for Rohingya women when they arrive at a health facility.61 While Rohingya is similar to the Bangladeshi Chittagonian dialect, it is only about 70% similar.62 The differences between these languages serve as significant barriers (and may affect the quality of care) for women receiving care in health facilities.24,63 The extent to which language barriers lead to delays both inside and outside of the camps has not been studied, however language barriers have been shown to cause delays in other contexts.64–66

There are multiple reports of discrimination against Rohingya patients in Bangladeshi health facilities prior to the current crisis which may affect care provision as well as have implications on the first delay. For example, in a report by MSF from 2007, a Ministry of Health doctor said, “The Rohingyas are exhausting hospital resources. Treatment should be for Bangladeshis. Staff was told not to treat them (Rohingyas) even if patients are dying in front of them.”67 The extent to which this impacts maternal mortality today by causing significant delays in delivery of care is unknown.68 Additionally, it is reported that government facilities may expect payment from referring NGO agencies when a refugee has an obstetric emergency, a practice that might result in delays for critically ill patients; this practice was reported by MSF in 2007.67 Rohingya are often treated in separate hospital wards called “Rohingya wards,” though it is unclear if service provision or quality differs in these areas.45

The way forward

While logistical and resource limitations impact maternal mortality in the Rohingya refugee camps, a complex set of social, political, and cultural factors create additional challenges for pregnant women.

With regard to the first delay, social and cultural norms prevent women from seeking care. Continued attention by UNFPA and health care providers to incorporating female voices in programming, including those of traditional birth attendants, is essential in improving women's comfort levels in seeking services. Recruiting women in positions of traditional authority, including female Hafes, or women that have memorised the Quran, to help promote facility-based birth in refugee communities may be helpful.24 Male leadership, husbands, and mothers-in-law need to be involved as well, as they are central to all health-related decision-making, as outlined above. Best practices might be uncovered in conversations with early adopters of facility-based births. Continued emphasis on provision of clean delivery kits to women and traditional birth attendants for home-based birth is essential. Priority should continue to be placed on programmes that engage traditional birth attendants and communities in identifying emergencies early, to allow such emergencies to be taken to facility-based care rapidly when needed.69

Encouraging facility-based births by providing scarce resources, such as cooking fuel, as incentives should be considered carefully with regard to unintended consequences, as provision of highly sought after assistance might result in women being put at risk for looting or murder.3,70 Initiatives to support facility-based births should also be implemented in the surrounding host communities, where these social and cultural norms also limit women's access to reproductive health care. Donors should fund and require robust programme evaluations that move beyond process outcomes at facilities to community-based, mixed-methods evaluations that incorporate ongoing community feedback from a broad representation of men and women. Research on the ways in which women's experiences with repressive reproductive health policies, sexual violence, and discrimination in health facilities in Myanmar affect health-seeking behaviour is necessary, with a focus on developing evidence-based solutions.

The second delay occurs once an obstetric emergency has been identified. Access to emergency transport can be challenging in these camps. While all-terrain vehicles with variable levels of staffing have been designated as ambulances in various parts of the camps, they are often not available at night and generally lack trained staff. Uniform, evidence-based protocols for emergency transport of critically ill patients has reduced mortality in other contexts.71 Additionally, a centralised emergency dispatch, a sort of camp “911”, might identify which ambulances are available and are nearest to the identified obstetric emergency, day or night. Based on the authors’ field experience with community health volunteers (CHVs), CHVs throughout the camps could provide a network of lay and trained emergency providers to ensure women receive timely transport to definitive care when needed. As recommended by Sphere standards, CEmONC facilities must be made available 24/7, with clear referral pathways and formal study of points of delay at each step, including study of the ways in which checkpoints and formal/informal payments may serve as barriers in the transfer process.17

The Bangladeshi government has mobilised significant resources to host Rohingya refugees. However, some government policies contribute to delays in care. Lack of Rohingya language interpreters and refugee movement out of camps result directly from government policies. The limited, difficult to navigate land provided by the government of Bangladesh for the refugee camps contributes to Phase II and III delays, as outlined above. The extent to which women experience discrimination in health facilities and the impact of these experiences on delivery of appropriate care requires further study. Such studies should be conducted in all facilities, including NGO and Ministry of Health clinics and hospital.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Centre for Injury Prevention and Research, Bangladesh (CIPRB), and UNFPA have completed a maternal mortality study, including one-year retrospective maternal mortality and verbal autopsies of probable maternal deaths, with the majority of data collected in late 2018. Preliminary findings have been presented to local aid personnel, and the full report is expected to follow soon. This group is also providing technical assistance to launch a community and facility-based maternal mortality surveillance system. Release of the report, findings of the verbal autopsies, and this surveillance system are likely to provide valuable insights into the delays outlined above.11

Finally, while Rohingya refugees have been given UNHCR identification cards, they continue to lack formal registration as refugees.72 Lack of refugee status limits their access to services in Bangladesh, access to durable solutions, as well as legal protections.40 Formal recognition as refugees, with all accompanying legal protections, access to livelihoods, and freedom of movement, is a necessary element of improving maternal mortality in these camps. Nearly 60 Rohingya women give birth every day in the refugee camps in Bangladesh.46

In the case of the Rohingya, it is necessary to address all sources of delay that contribute to maternal mortality – including those that result from political constraints, in order to ensure women's lives are protected.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Rowen O Jin http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6073-8838

References

- 1.Maternal mortality in humanitarian crises and in fragile settings [cited 2019 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/MMR_in_humanitarian_settings-final4_0.pdf.

- 2.Minimum Initial Service Package - Welcome to the Inter-agency Working Group (IAWG) [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: http://iawg.net/minimum-initial-service-package/

- 3.IOM Bangladesh Needs and population monitoring (NPM) site assessment round 13; 2018. Available from: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/iom-bangladesh-needs-and-population-monitoring-npm-round-13-site-assessment.

- 4.Smith M. Policies of persecution ending abusive state policies against. 2014; (February):79.

- 5.Human Rights Watch Burmese refugees in Bangladesh: still no durable solution; 2000. [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/burm005.PDF.

- 6.Mahmood SS, Wroe E, Fuller A, et al. The Rohingya people of Myanmar: health, human rights, and identity. Lancet. 2017;389(10081):1841–1850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00646-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akhter S, Kusakabe K.. Gender-based violence among documented Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Indian J Gend Stud. 2014;21(2):225–246. doi: 10.1177/0971521514525088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewa C. Northern Arakan: an open prison for the Rohingya in Burma. Forced Migr Rev. 2009;32:11–13. [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: http://www.myanmar.gov.mm/ministry/hotel/fact/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Human Rights Council Human rights situations that require the council’s attention. Report of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar. Thirty-Ninth Session, Agenda Item 4, 2018 Sept 10–28. [cited 2019 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/FFM-Myanmar/A_HRC_39_64.pdf.

- 10.Situation Refugee Response in Bangladesh [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/myanmar_refugees.

- 11.Preliminary Findings from CDC RAMOS study SRH Working Group, Cox’s Bazar, March; 2019.

- 12.UNFPA, UNHCR I Joint Response Plan for Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis: January to December 2019; 2019. [cited 2019 Mar 26]. Available from: www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/bangladesh.

- 13.Minimum Initial Service Package [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/MISP_Objectives.pdf.

- 14.Guzek J, Siddiqui R, White K. Health Survey in Kutupalong and Balukhali Refugee Settlements. Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh survey report; 2017. [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.msf.org/sites/msf.org/files/coxsbazar_healthsurveyreport_dec2017_final1.pdf.

- 15.Mahmood I, Biswas N, Akter F, et al. Burden of Obstetric Fistula on the Rohingya Community in Cox’s; 1982.

- 16.IAWG Women and girls critically underserved in the rohingya humanitarian response; 2018. Available from: www.iawg.net.

- 17.The Sphere Handbook Standards for quality humanitarian response. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://handbook.spherestandards.org/.

- 18.Health sector Cox’s Bazar Secondary Referral Map.

- 19.Rogers K. Nothing could have prepared me for Cox’s Bazar, reproductive health expert says. Devex. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.devex.com/news/q-a-nothing-could-have-prepared-me-for-cox-s-bazar-reproductive-health-expert-says-91949.

- 20.Raha RP, Basri R. Comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care in humanitarian setting: a qualitative approach among midwives in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh; 2018. Available from: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1265886&dswid=2989.

- 21.UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund Bangladesh Humanitarian Emergency. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/data/emergencies/bangladesh-humanitarian-emergency.

- 22.Monitoring emergency obstetric care a handbook [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/obstetric_monitoring.pdf.

- 23.Thaddeus S, Maine D.. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–1110. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8042057 doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ripoll S, Annex CS.. Social and cultural factors shaping heath and nutrition, wellbeing and protection of the Rohingya within the humanitarian context. Soc Sci Humanit Action. 2017:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Human Rights Watch Burma: revoke ‘two-child policy’ for Rohingya. [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/05/28/burma-revoke-two-child-policy-rohingya.

- 26.A gender analysis of the right to a nationality in Myanmar; 2018.

- 27.Perria S. Burma’s birth control law exposes Buddhist fear of Muslim minority. The Guardian. 2015 May 24.

- 28.Mahmood SS, Wroe E, Fuller A, et al. The Rohingya people of Myanmar: health, human rights, and identity. Lancet. 2017;389(10081):1841–1850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00646-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of State BURMA 2014 Human Rights Report; 2014. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/236640.pdf.

- 30.Ba-Thike K. Abortion: a public health problem in Myanmar. Reprod Health Matters. 1997;9:94–100. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(97)90010-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amnesty International Caged without a roof; 2017. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: www.amnesty.org.

- 32.McLaughlin T. Myanmar publishes census, but Rohingya minority not recognized. Reuters; 2017.

- 33.Human Rights Watch Joint Submission to CEDAW on Myanmar. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/05/24/joint-submission-cedaw-myanmar.

- 34.Skye Wheeler All My Body Was Pain; 2017. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/burma1117_web_1.pdf.

- 35.UN Women Gender brief on Rohingya refugee crisis response in Bangladesh; 2018. [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/bangladesh/family-counting-interactive-dashboard.

- 36.Human Rights Watch All you can do is pray; crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in Burma’s Arakan State; 2013. [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: http://www.hrw.org.

- 37.Human Rights Watch Burma: Methodical Massacre at Rohingya Village. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/12/19/burma-methodical-massacre-rohingya-village.

- 38.UNFPA Asiapacific Horrific stories, urgent action: addressing gender-based violence amid the Rohingya refugee crisis. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/news/addressing-gender-based-violence-amid-rohingya-refugee-crisis-horrific-stories-urgent-action-0.

- 39.Islam MM, Nuzhath T.. Health risks of Rohingya refugee population in Bangladesh: a call for global attention. J Glob Health. 2018;8: 020309. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.020309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UN News For Rohingya refugees, imminent surge in births is traumatic legacy of sexual violence - special report. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/05/1009372.

- 41.Doctors Without Borders – USA Rohingya refugees: Still searching for safety. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/rohingya-refugees-still-searching-safety.

- 42.Therien A, Leroux E-A.. Sexual and Reproductive Health Working Group. Quarterly Bulletin Issue 1; 2018 Dec–Feb.

- 43.BRAC’s Humanitarian Response in Cox’s Bazar Strategy for 2018; 2018.

- 44.Current level of knowledge, attitudes, practices, and behaviours (KAPB) of the Rohingya Refugees and Host Community in Cox’s Bazar: a report on findings from the baseline survey; 2018.

- 45.Bangladesh to offer sterilisation to Rohingya in refugee camps . The Guardian. 2017 Oct 27.

- 46.Women and Girls in Bangladesh: Health Survey; 2005.

- 47. ARSA: end abductions, torture, threats against Rohingya refugees and women aid workers. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.fortifyrights.org/publication-20190314.html.

- 48.ISCG Gender profile no.1 for Rohingya refugee crisis response Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh; 2017;(1):1-13. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/iscg_gender_profile_rohingya_ref%0Agee_crisis_response_final_3_december_2017_.pdf.

- 49.Toma I, Chowdhury M, Laiju M, et al. Rohingya Refugee response gender analysis: recognizing and responding to gender inequalities; 2017. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/rr-rohingya-refugee-response-gender-analysis-010818-en.pdf.

- 50.Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh Gender Profile No.2 For Rohingya Refugee Crisis Response; 2019;11(2):1-12. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/iscg_gender_profile_rohingya_refugee_crisis_response_final_3_december_2017_.pdf.

- 51. Rohingya crisis Governance and Community Participation; 2018. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/products/files/20180606_acaps_npm_report_camp_governance_final_0.pdf.

- 52. [52] The World Bank. Maternal mortality ratio. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT?locations=BD.

- 53.ReliefWeb Making sexual and reproductive health services a priority for Rohingya refugees and host communities – Bangladesh. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/making-sexual-and-reproductive-health-services-priority-rohingya-refugees-and-host.

- 54. The Rohingya Amongst Us: Bangladeshi Perspectives on the Rohingya Crisis Survey; 2018. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: http://xchange.org/bangladeshi-perspectives-on-the-rohingya-crisis-survey/

- 55.International Organization for Migration IOM deploys new ambulance fleet to serve Rohingya refugees, local community in Bangladesh camps. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.iom.int/news/iom-deploys-new-ambulance-fleet-serve-rohingya-refugees-local-community-bangladesh-camps.

- 56.Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International Bangladesh: this feels more like an emergency room than a normal delivery room. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.msf.org/bangladesh-feels-more-emergency-room-normal-delivery-room.

- 57.UNHCR The 1951 Refugee Convention. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/1951-refugee-convention.html.

- 58.Dhaka Tribune From now on Rohingya will be called “forcefully displaced Myanmar citizens.” [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2017/10/05/now-rohingya-will-called-forcefully-displaced-myanmar-citizens/

- 59.Cox’s Bazar Sadar U IOM NPM R10 report population, distribution and demographics; 2018 [cited 2019 Mar 22]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/npm_round_10_report_may_2018.pdf.

- 60.Hasnat Milton A, Rahman M, Hussain S, et al. 10.3390/ijerph14080942. [DOI]

- 61.Inter Sector Coordination Group Refugee volunteer incentive rates – Rohingya refugee response; 2018. Available from: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/bangladesh/document/harmonization-semi-skilled-and-skilled-refugee-volunteer-incentive.

- 62.WBUR News Finding the right words to help Rohingya refugees. [cited 2019 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.wbur.org/npr/630858182/finding-the-right-words-to-help-rohingya-refugees.

- 63.Vigaud-Walsh F. 10.29171/azu_acku_pamphlet_hv4132_6_a5_s756_2014. [DOI]

- 64.Gurnah K, Khoshnood K, Bradley E, et al. Lost in translation: reproductive health care experiences of Somali Bantu women in Hartford, Connecticut. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56(4):340–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00028.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Esscher A, Binder-Finnema P, Bødker B, et al. Suboptimal care and maternal mortality among foreign-born women in Sweden: maternal death audit with application of the “migration three delays” model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:141 [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/14/141 doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bowen S. The impact of language barriers on patient safety and quality of care final report prepared for the Société Santé En Français; 2015. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: http://www.reseausantene.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Impact-language-barrier-qualitysafety.pdf.

- 67. The Rohingya people from Myanmar seeking refuge in Bangladesh. An MSF Briefing Paper; 2007. [cited Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.msf.org/sites/msf.org/files/old-cms/fms/article-images/2007-00/msf_stateless_rohingyas_biefing_paper.pdf.

- 68.Lewa C. We are like a soccer ball, kicked by Burma, kicked by Bangladesh!: Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are facing a new drive of involuntary repatriation. Report. Bangkok: FORUM-ASIA; 2003. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.worldcat.org/title/we-are-like-a-soccer-ball-kicked-by-burma-kicked-by-bangladesh-rohingya-refugees-in-bangladesh-are-facing-a-new-drive-of-involuntary-repatriation-report/oclc/56766984.

- 69.UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund Reaching “forgotten” Rohingya in Myanmar cut off from basic maternal care. [cited 2019 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/news/reaching-forgotten-rohingya-myanmar-cut-basic-maternal-care.

- 70.Perrin P. The impact of humanitarian aid on conflict development. ICRC – International Committee of the Red Cross; 1998 [cited 2019 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/article/other/57jpcj.htm.

- 71.Schoon MG. Impact of inter-facility transport on maternal mortality in the free state province. South African Med J. 2013;103(8):534–537. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.6828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.UN News New identity cards deliver recognition and protection for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/07/1014082.