Abstract

Adolescent girls comprise a considerable proportion of annual abortion deaths, worldwide, with 15% of all unsafe abortions taking place among girls under 20 years of age. Despite recent global attention to the health and welfare of adolescent girls, little is known about their abortion experience, particularly of those under the age of 15 years. This review examines existing peer-reviewed and grey literature on abortion-related experiences of adolescent girls, paying particular attention to girls ages 10–14. In December 2019, the authors conducted a comprehensive search of five major online resource databases, using a two-part keyword search strategy for articles from 2003 to 2019. Of the original 3,100+ articles, 1,228 were individually screened and 35 retained for inclusion in the analysis. Findings show that while adolescent girls may have knowledge of abortion in general, they lack specific knowledge of sources of care and delay care-seeking due to the fear of stigma, lack of resources and provider bias. Adolescent girls do not experience higher rates of physical complications compared to older cohorts, but they are at risk of psychosocial harm. For girls ages 10–14, abortion experience may be compounded by pregnancy due to sexual abuse or transactional sex, and they face even more barriers to care than older adolescents in terms of provider bias and lack of agency. Adolescents have unique needs and experiences around abortion, which should be accounted for in programming and advocacy. Adolescent girls need information about safe abortion at an early age and a responsive and stigma-free health system.

Keywords: abortion, adolescents, unsafe abortion, sexual health, reproductive health

Résumé

Dans le monde, les adolescentes représentent une proportion considérable des décès annuels dus à l’avortement, avec 15% de tous les avortements à risque étant pratiqués sur des filles âgées de moins de 20 ans. En dépit de l’attention mondiale récemment accordée à la santé et au bien-être des adolescentes, on sait peu de choses de leur expérience de l’avortement, en particulier pour celles qui ont moins de 15 ans. Cette analyse examine les publications à comité de lecture et la littérature grise sur l’expérience des adolescentes en rapport avec l’avortement, en s’intéressant particulièrement aux filles âgées de 10 à 14 ans. En décembre 2019, les auteurs ont réalisé une recherche exhaustive de cinq bases de données majeures de ressources en ligne, à l’aide d’une stratégie de recherche par mot clé en deux parties pour les articles de 2003 à 2019. Sur les plus de 3100 articles, 1228 ont été sélectionnés individuellement et 35 retenus pour être inclus dans l’analyse. Les conclusions montrent que si les adolescentes peuvent avoir des connaissances générales sur l’avortement, elles manquent de renseignements précis sur les sources de soins et retardent la demande de soins par crainte de la stigmatisation, manque de ressources et préjugés des prestataires. Les adolescentes ne connaissent pas de taux plus élevés de complications physiques que des cohortes plus âgées, mais elles risquent des dommages psychosociaux. Chez les filles âgées de 10 à 14 ans, l’expérience de l’avortement peut être aggravée par le fait que la grossesse était due à un abus sexuel ou à des relations sexuelles transactionnelles, et elles rencontrent des obstacles encore plus nombreux pour obtenir des soins que les adolescentes plus âgées, du point de vue des préjugés des prestataires et du manque de pouvoir. Les adolescents ont des besoins et des expériences uniques autour de l’avortement, dont il faudrait tenir compte dans la programmation et le plaidoyer. Les adolescentes ont besoin d’informations sur l’avortement sûr à un âge précoce ainsi que d’un système de santé réactif et qui ne les stigmatise pas.

Resumen

Un considerable porcentaje de muertes anuales atribuibles al aborto ocurre entre adolescentes a nivel mundial, ya que el 15% de todos los abortos inseguros ocurren entre niñas menores de 20 años. A pesar de la atención mundial reciente a la salud y el bienestar de las adolescentes, no se sabe mucho sobre su experiencia de aborto, en particular entre aquéllas menores de 15 años. Esta revisión examina la literatura existente revisada por pares y la literatura gris sobre las experiencias de las adolescentes con relación al aborto, y presta particular atención a niñas entre 10 y 14 años. En diciembre de 2019, los autores realizaron una búsqueda integral en cinco principales bases de datos de recursos en línea, utilizando una estrategia de búsqueda con palabras clave de dos partes de artículos publicados entre los años 2003 y 2019. De los 3,100+ artículos originales, 1,228 fueron examinados individualmente y 35 fueron retenidos para su inclusión en el análisis. Los hallazgos muestran que, aunque las adolescentes tengan conocimientos generales del aborto, carecen de conocimientos específicos sobre las fuentes de servicios y retrasan la búsqueda de atención por temor al estigma, falta de recursos y prejuicios del personal de salud. Las adolescentes no presentan mayores tasas de complicaciones físicas comparadas con grupos de mujeres de edad más avanzada, pero corren riesgo de sufrir daños psicosociales. La experiencia de aborto de niñas entre 10 y 14 años podría verse agravada en casos de embarazo producido por abuso sexual o sexo transaccional; además, estas niñas enfrentan aun más barreras para obtener servicios que las adolescentes mayores, por los prejuicios del personal de salud y la falta de agencia. Las adolescentes tienen necesidades y experiencias únicas con relación al aborto, las cuales deben tomarse en consideración en los programas y en las actividades de promoción y defensa. Las adolescentes necesitan información sobre el aborto seguro a temprana edad y un sistema de salud receptivo y libre de estigma.

Background

Each year, an estimated 3.2 million unsafe abortions (defined as a pregnancy termination performed either by a person lacking the necessary skills or in an environment lacking adequate medical standards) take place among adolescent girls ages 15–19. This number accounts for almost 15% of the total global incidence of unsafe abortion (22 million), and abortion-related mortality among young girls and women accounts for nearly one-third of abortion-related deaths worldwide.1 Despite recently increased commitments to adolescent reproductive health, our understanding of their abortion experiences is limited. Furthermore, the focus of policy and programmatic attention remains primarily on adolescents ages 15–19, leaving a substantial gap in our understanding of the sexual and reproductive experiences of adolescents ages 10–14.2–4 Girls in this category comprise a large and growing segment of the population, particularly in highly impoverished regions of the world (estimated at 545 million in 2015).5 A parallel increase in the age of marriage in many contexts has extended the period of premarital fertility, which further exposes young adolescents to the risk of unintended pregnancy resulting in unsafe abortion.6–8 Moreover, the majority of unsafe abortion incidence is concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) where the 10–14-year-old population is proportionally largest, and where many countries have restrictive abortion laws.9,10

The potential for sexual and reproductive harm among adolescents is a present and growing threat, yet our understanding of abortion in this group is insufficient to properly address their needs through programmatic and policy interventions. The purpose of this literature review is to explore abortion-related knowledge, attitudes and experiences of adolescent girls, paying particular attention to those ages 10–14.

Methods

This literature review focused on the abortion knowledge, experiences and attitudes of younger (10–14 years) and older (15–19 years) adolescents from LMIC (as defined by the World Bank).11

Data sources

We conducted a systematic search of five online resource databases: PubMed, Global Health, Embase, POPLINE and Google Scholar, between June 2018 and December 2019. In addition, we searched websites of organisations that do sexual and reproductive health work with adolescents to locate any additional grey literature. These organisations included Ipas, International Planned Parenthood Federation, Guttmacher Institute, Marie Stopes International and EngenderHealth. We also conducted a general search of the Google search engine to locate any additional grey literature sources.

Search strategy

The search covered the time frame between 2003 and 2019 and was run simultaneously by GS and CE. Databases were searched using a two-part keyword search strategy. The first set of search terms focused on limiting the age group of target populations to only adolescents and included “Adolesc”* OR “young” OR “youth”* OR “girl”* OR “very young girl”* OR “very young adolesc”* OR “adolescent health services”* OR “child” OR “pregnancy in adolescence”. The second set of search terms related to abortion experience and included “Abortion” OR “termination of pregnancy” OR “pregnancy termination” OR “menstrual regulation” OR “postabortion” OR “abortion, induced”OR “abortion applicants”. These terms were used in combination with “tiab” and “MeSH” settings to maximise the identification of keywords in indexed articles in the databases.

Selection criteria

The search included all English, Spanish and French language† peer-reviewed publications of either quantitative or qualitative nature related to the abortion knowledge, attitudes or experience of adolescents ages 10–19. The search was restricted to articles that included findings from adolescents 19 years or younger years of age, meaning articles that included women from older age groups were included so long as data were segregated by age groups and findings for adolescents under 20 years of age could be differentiated from that of older women. The primary focus of this review is on adolescents from low- to middle-income countries.

Articles were excluded if they did not include findings from primary data collection or original secondary analysis of a primary data source, if they did not include data on the abortion experience, knowledge or attitudes of adolescents under the age of 20 years or did not come from an LMIC, with one exception: given that data on younger adolescents are sparse, if a study included segregated data on 10–14-year-olds, it was included in the review regardless of the LMIC status of the sample.

Screening and selection

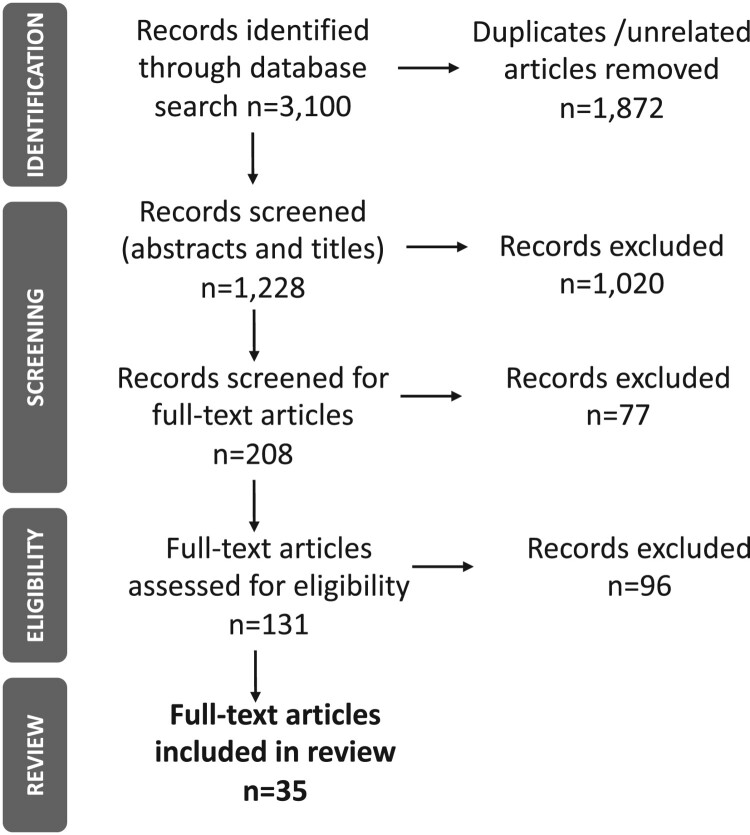

We conducted screening and selection using the PRISMA guidelines (Figure 1).12 The search yielded over 3,100 articles, many of which included either duplicate articles of studies pertaining to clinical findings not suitable for the topic of this review (such as unrelated obstetric outcomes). The screening process was multi-stage, whereby first we removed all duplicates and clearly irrelevant articles (for example articles that pertained to highly technical obstetric procedures). We then performed an initial screening based on the abstracts retrieved in the first stage of the search. In this first pass, the reviewer erred on the side of inclusion, so as not to accidentally omit articles that may have provided relevant data in full-text form. After the initial abstract review, we conducted a third screening of full-text articles; only studies for which the full text was available either in English, French or Spanish were retained (as these were the working languages of the authors). Each article was then reviewed for quality by GS and CE using the critical appraisal skills programme checklist for both quantitative and qualitative studies.13

Figure 1.

PRISMA screening process

Data abstraction and analysis

The articles were abstracted in terms of their publication details (authors, date, title, etc.), geographic scope, purpose, study design, population, methods and main findings. The articles were coded by hand into thematic areas that emerged from initial reading and organisation of the articles. The themes evolved over the course of coding, and the final list of themes included abortion knowledge and attitudes, comparative abortion rates for adolescents versus older women, reasons for abortion, the timing of abortion and postabortion care, sources and methods of abortion, experiences with formal health providers, the experience of complications of abortion, and psychosocial outcomes of abortion. Articles could be assigned more than one code and thus may appear under more than one thematic area.

Results

A total of 35 articles were included in this review (Table 1); five were qualitative, one used mixed methods, and the rest (n = 29) were quantitative. Twenty-three of the articles were from Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g. Cote d’Ivoire = 1, the Democratic Republic of Congo = 1, Ethiopia = 4, Ghana = 1, Kenya = 2, Malawi = 3, Nigeria = 5, South Africa = 1, Uganda = 1 and Zambia = 1), 6 from Asia (e.g. Bangladesh = 1, India = 1 Japan = 1, Nepal = 1 Thailand = 2) and 6 from the Americas (Brazil = 3, Guadeloupe = 1, Mexico = 2). Sample sizes for the study ranged considerably depending on the method (quantitative versus qualitative) and the focus and design of the study; the largest study involved a national health records review (115,490 live birth records reviewed quantitatively in Thailand) while the smallest was an exploratory qualitative study of 16 girls in Malawi. The results of the study are presented in terms of two broad categories: knowledge/attitudes towards abortion and abortion experience. The category of abortion experience is further divided into abortion rates (comparing <19 girls with other age groups), reasons for abortion, timing and methods used for abortion, complications of abortion, experiences with providers, and psycho-social outcomes. Within these categories, there may be a combination of results pertaining to 15–19 and 10–14-year-old adolescents.

Table 1. Summary of studies (n = 35).

| Authors | Year | Title | Geographic scope | Study design | Study period | Population | N | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abiola, A. H. O., et al | 2016 | Knowledge, attitude, and practice of abortion among female students of two public senior secondary schools in Lagos Mainland Local Government Area, Lagos State | Lagos, Nigeria | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | NA | Girls ages 10–14, 15–19 | 206 | 83.3% of respondents had the knowledge of abortion; 99.2% demonstrated poor attitude towards abortion; 2%had ever had an abortion. 10–14-year-olds were MORE likely to have knowledge of abortion legality/processes, but a LESS positive attitude towards abortion compared to 15–19-year-olds. |

| Adaji, S. E., et al | 2010 | The attitudes of Kenyan in-school adolescents toward sexual autonomy | Kenya | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2002 | Boys and girls ages 13–19 | 1159 | 91.6% of females and 86.9% of males disagree with abortion for girls with an unwanted pregnancy (p=0.007). |

| Ahmed, M et al | 2005 | Factors associated with adolescent abortion in a rural area of Bangladesh | Bangladesh | A quantitative, Matlab Health and Demographic Surveillance System | 1982–98 | Women of all ages, separated by <18 vs older women or vs 18–19 | 16137 (<18 = 4669) | 20 vs 733 abortions per 1,000 births (p<0.001) for married versus unmarried adolescents. 73% of all out-of-wedlock pregnancies of adolescents and 66% of adults were aborted. |

| Ake-Tano, S. O. P., et al | 2017 | Abortion practices in high school students in Yamoussoukro, Cote d’Ivoire | Cote d’Ivoire | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2011 | Girls 11–19 | 312 | 61.7% of girls had already had an abortion. Abortion pathway was as follows: the main method was self-prescribed medication (70%) as the first attempt, followed, in the case of failure, by traditional healers (56.4%). Healthcare practitioners at the third attempt (85.7%). Methods of abortion were drugs (91.9%), ingestion of plants/beverages (68.5%) and foreign objects inserted (62.3%). 44% resulted in complications, significantly associated with self-induced abortions or abortions performed by traditional healers (p < 0.001). |

| Akinlusi, F. M., et al | 2018 | Complicated unsafe abortion in a Nigerian teaching hospital: pattern of morbidity and mortality | Nigeria | A quantitative, retrospective review | 2003–2007 | Women ages 16–40+ | 3122 | Adolescents (16–20 years) comprised the largest age group for unsafe abortion (29%). |

| Areemit, R., et al | 2012 | Adolescent pregnancy: Thailand’s national agenda | Thailand | A quantitative, retrospective review | 2010 | Girls ages 10–14, 15–19 | 11662 (abortions) | 15–19-year-olds comprised 18.0% of all abortions. The abortion rate in adolescents was less than for the 20–34-year-olds group; 23.0% in the younger adolescents but 14.2 in the older adolescent groups. Among 10–14-year-olds, there was a significantly higher probability of abortion (OR = 1.18) than among women in 20–24 age group, while 15–19-year-olds had a significantly lower probability of abortion (OR = 0.65). |

| Atuyambe, L., et al | 2005 | Experiences of pregnant adolescents – voices from Wakiso district, Uganda | Uganda | A qualitative, exploratory study | 2002 | pregnant adolescents | 50 | Unmarried adolescent pregnant girls abort due to rejection by partners, forced abortion by parents. Having an older partner may increase the risk of abortion. |

| Aung, E.E., et al | 2018 | Years of healthy life lost due to adverse pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers in Thailand | Thailand | A qualitative, secondary data analysis of vital registration data | 2014 | Adolescent girls ages 10–19 | 115,490 live births to adolescents | Total of 725 DALYs lost and 262 years of life (YLL) lost due to complications from unsafe abortion, accounting for 34% of all DALYs lost for girls ages 10–19 and resulting in the highest burden of nonfatal morbidity. Among 10–14-year-olds, # of abortion cases = 35, YLL = 0, DALYs = 26, abortion rate = 1,086 per 100,00 live births; Among 15–19-year-olds, # of abortion cases=675, YLL = 262, DALYs=699, abortion rate=602 per 100,000 live births. |

| Baba, S., et al | 2014 | Recent pregnancy trends among early adolescent girls in Japan | Japan | A quantitative, retrospective time trend analysis | 2003–2010 | Adolescent girls <15, 15–19 | 3096 | Abortion ratios of <15 higher than those of 15–19-year-olds. A significant correlation between abortion and juvenile victimisation of welfare crimes (obscenity, alcohol drinking, smoking and drug use). Timing of abortion for <15 is at a much later stage than that for older women. |

| Bailey, P. E., et al | 2003 | Adolescents’ decision-making and attitudes towards abortion in north-east Brazil | Brazil | A quantitative, cohort study | 1998 | Girls ages 12–18 at baseline | 367 | 13% of the induced abortion patients were in union compared with 60% of the adolescents with intended pregnancies. 68% of induced abortion patients enrolled in school; 33% induced abortion patients were working. |

| Bain, L. E., et al | 2019 | To keep or not to keep? Decision making in adolescent pregnancies in Jamestown, Ghana | Ghana | Qualitative, cross-sectional semi-structured interviews | N/A | Adolescent girls ages 14–19 | 30 | 87.0% of adolescents who had an abortion did so under unsafe circumstances. Barriers to safe abortion: lack of abortion law knowledge, stigma, high cost of safe abortion service fees, and distrust in the health care providers. Religion did not play a large role. |

| Bilal, S. M., et al | 2015 | Utilisation of sexual and reproductive health services in Ethiopia – does it affect sexual activity among high school students? | Ethiopia | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2009 | Girls and boys ages 14–19 | 1031 | 82% of pregnancies terminated at home; 57% abortion in a health facility, 42% at home. |

| Bonnen, K. I., et al | 2014 | Determinants of first and second trimester-induced abortion – results from a cross-sectional study taken place 7 years after abortion law revisions in Ethiopia | Ethiopia | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2011–212 | All women, data presented by <19 vs others | 829 | Among 19 or younger, OR of having an abortion in the second trimester is 2.6 relative to having an abortion in the first trimester, compared to women aged 25+ years (CI: 1.23-5.68). |

| Chamanga, R. P., et al | 2012 | Psychological distress among adolescents before, during and after unsafe induced abortion in Malawi. | Malawi | A qualitative, exploratory study | NA | Girls ages 14–16, 17–19 | 16 | Before abortion: worry about parents’ discovery, dropping out of school, the stigma around premarital pregnancy, worry about abuse from providers; worry contributed to delay in seeking care for abortion complications. After abortion: guilt/regret for religious reasons, loss/grief because of circumstantial reasons for the abortion (might have wanted to keep baby under better circumstances). |

| Clyde et al | 2013 | Evolving capacity and decision-making in practice: adolescents’ access to legal abortion services in Mexico City | Mexico | Mixed methods cross-sectional | 2009 | Girls ages 12–17 | 61 | Providers are generally positive about adolescents’ ability to decide on abortion, no clear understanding of adult accompaniment. Mystery clients are seeking information more likely to receive complete information if accompanied by an adult. |

| Correia, D. S., et al | 2009 | Induced abortion: risk factors for adolescent female students, a Brazilian study | Brazil | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2005 | Girls ages 12–14, 15–19 | 559 | 20.3% of sexually active 12–14-year-olds had an abortion, 27.3% of sexually active 15–19-year-olds had an abortion; abortion less likely in 12–14-year-old group. For abortion, 63.8% of them had support, 83.9% did not have physical complications, and 89.3% did not need hospitalisation. |

| Dahlback, E., et al. | 2010 | Pregnancy loss: spontaneous and induced abortions among young women in Lusaka, Zambia | Zambia | Quantitative, prospective exploratory design | 2005 | Girls ages 12–19; 13–16 vs 17–19 | 87 | No significant difference between rates of induced abortion between 13–16-year-olds v 17–19-year-olds; Common reasons to perform clandestine abortions: wish to continue schooling, not to spoil their future aspiration, fear of their parents’ reaction, to alleviate the social shame and the financial burden on their family. The majority (76%) of induced abortions took place at home; traditional healers were one of the major providers (67%). |

| de Wet, N. | 2016 | Pregnancy and death: an examination of pregnancy-related deaths among adolescents in the South. | South Africa | A quantitative, retrospective review | 2006–2012 | Girls <19 | 13930 | Abortion accounted for 17.6% of deaths in pregnant adolescent females over the period; More adult deaths owing to abortion than adolescent deaths, with maternal mortality ratios of 7.56 and 4.20, respectively. |

| Flory, F., et al. | 2014 | Sociodemographic and medical features of abortion among underage people in Guadeloupe (French West Indies) | Guadeloupe | A quantitative, retrospective study | 2010 | Girls <18 | 129 | Main motivations for abortion were continuing studies and young age. Abortion occurs after 9 weeks of amenorrhoea in 55.1% and 43.3% of underage people reported psychological problems linked to the abortion (mainly distress over worse relationship with parents). |

| Gebreselassie, H., et al. | 2005 | The magnitude of abortion complications in Kenya | Kenya | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2002 | all women, data presented by <20 | 809 | Adolescents (14–19 years old) accounted for approximately 16% of the study sample. Also, the odds of having evidence of mechanical injury among adolescents were twice that of adult women (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.0–4.1). |

| Kebede, M. M., et al | 2016 | Knowledge of Abortion Legislation Towards Induced Abortion Among Female Preparatory School Students in Dabat District, Ethiopia | Ethiopia | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2014 | Girls <18, 18–20, >20 | 234 | 62.8% know the law allows safe and legal abortion under certain circumstances. 41.5% have poor knowledge of legality. Higher family income (OR=2.63, 95% CI=1.22–5.63), knowing the place where safely induced abortion can be performed (2.51, 95%CI=1.31–4.81) and current use of contraceptive (OR=2.3, 95% CI, 1.1–4.81) are significantly associated with knowledge of the abortion legislation. No difference between younger and older adolescents. |

| Kyilleh, J. M., et al | 2018 | Adolescents’ reproductive health knowledge, choices and factors affecting reproductive health choices: a qualitative study in the West Gonja District in Northern Region, Ghana | Ghana | A qualitative narrative study | 2016 | Girls 10–19; and health care providers | 80 (male and female) | Unsafe methods of abortion include: boiled pawpaw leaves, Nescafe, ground-up bottles, alcoholic beverages and inserting herbs into the vagina. Adolescents felt providers did not provide enough privacy and confidentiality and sometimes told parents of adolescents who seek such services. Providers believe increasing access to comprehensive abortion services will encourage sexual activity among adolescents. |

| Lema, V. M. | 2003 | Reproductive awareness behaviour and profiles of adolescent post abortion patients in Blantyre, Malawi. | Malawi | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 1997 | Girls <19 | 465 | 10–19 comprised 27.6% of all abortions, second largest after 20–24 group; Of those who said pregnancy was due to unwanted sex, 86.6% reported that they were either assaulted or forced to have sexual intercourse by someone well known to them, 10.4% did it to please the man, 3% did it in exchange for favours, money or goods. |

| Levandowski, B. A., et al | 2012 | Reproductive health characteristics of young Malawian women seeking post-abortion care | Malawi | A quantitative, prospective morbidity study | 2009 | Girls 10–19, older age groups | 2076 | 20.9% of PAC clients were adolescents (age 10–19); 10–19-year-olds had 3.5 times more mechanical injury than others. Among the 10–19-year-olds, those who were unmarried were 11.0 times more likely to report abortion compared to married women of the same group (95%CI 3.07–39.4). |

| Mehata, S., et al | 2019 | Factors associated with induced abortion in Nepal: data from a nationally representative population-based cross-sectional survey | Nepal | A quantitative, secondary data analysis of national survey | 2016 | Women ages 15–49, <20 age group data presented | 12,862 | Compared to women aged < 20 years, women aged 20–34 years had higher odds (AOR: 5.54; 95% CI: 2.87–10.72) of having had an abortion in the past 5 years. |

| Mitchell, E. M., et al. | 2014 | Brazilian adolescents’ knowledge and beliefs about abortion methods: A school-based internet inquiry. | Brazil | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2003–2006 | Girls and boys 12–21, | 559 | 32% of 12–14-year-olds and 52% of 15–16-year-old knew a person who had had an abortion; 45% overall knew of someone; 29% knew of a method of abortion (12–14yo), 40% of 15–16-year-olds knew a method; legal termination supported by 56% of total students; Most abortion methods (79.3%) reported were ineffective, obsolete, and/or unsafe. Herbs (e.g. marijuana tea), over-the-counter medications, surgical procedures, foreign objects and blunt trauma were reported. |

| Murray, N., et al | 2014 | Factors related to induced abortion among young women in Edo State, Nigeria | Nigeria | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2002 | Women ages 15–24 | 599 | 68% of 15–19-year-olds report having had at least one abortion, compared with 57% of 20–24-year-olds in the ever-pregnant sample. Young women unmarried at the time of the interview are found to be significantly more likely than married women to have had an abortion. Young women who have experienced transactional or forced sex are also significantly more likely to report ever having had an abortion, as are young women who have experienced more than one pregnancy. |

| Paluku, L. J., et al | 2010 | Knowledge and attitude of schoolgirls about illegal abortions in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo | DRC | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2003 | Girls ages 16–20 | 328 | 9.8% had committed an abortion before and 46% knew where to obtain it; 76.2% were against illegal abortion and 77.1% of participants knew someone who had committed an illegal abortion. |

| Prabhu, T. R. | 2014 | Legal abortions in the unmarried women: social issues revisited | India | A quantitative, observational study | 2006–2010 | Girls ages <16, 17–19, older age groups | 115 | Majority of unmarried women seeking abortions are less than 20 years of age. 15.6% of the subjects were <16 years of age, and 40.8% were between 17 and 19 years of age. 72% reported for termination in the second trimester. |

| Ramakuela, N. J., et al | 2016 | Views of teenagers on termination of pregnancy at Muyexe high school in Mopani District, Limpopo Province, South Africa | South Africa | A qualitative, exploratory study with qual | NA | Girls ages 15–19 | 25 | Reasons for abortion included: poverty, relationship problems and single parenthood, desire to continue school, fear of stigma from friends/parents, pregnancy result of rape/incest, fear of giving birth. |

| Schiavon R., | 2012 | Increasing abortion-related hospitalisation rates among adolescents in Mexico in the last decade, by age group and by state of residence | Mexico | A quantitative, secondary data analysis | 2000–2010 | Girls 10–14, 15–19 | 11,183 | Hospitalisations among adolescents (10–19-years-old) accounted for 22.8% of all cases. The increase in abortion rates was also notable among the 10–14-year-olds. Older groups, where abortion went from 13.6% of Live Births in 2000 up to 16.3% in 2010. |

| Sully, E., et al | 2018 | Playing it Safe: Legal and Clandestine Abortions Among Adolescents in Ethiopia | Ethiopia | A quantitative, secondary data analysis | 2014 | Girls 15–19, older ages | NA | Adolescents (15–19-years-old) have the lowest abortion rate among all women less than 35 years of age (19.6 abortions per 1,000 women). Adolescents have the highest abortion rate among all age-groups and highest proportion (64%) of legal abortions compared with other age-groups. No differences in the severity of abortion-related complications between 15–19-year-olds and older women. |

| Tunde, A. I. | 2013 | Socio-economical and sociological factors as predictors of illegal abortion among adolescent in Akoko West local government area of Ondo state, Nigeria | Nigeria | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | NA | Girls ages 14–21 | 500 | Poverty, dropping out of school, level of education and inadequate medical personnel, facilities and equipment were predictors to illegal abortion among adolescents. Poverty and socio-economic factors sometimes lead adolescents into prostitution which results in unwanted pregnancy and illegal abortion. |

| Ujah, I. A., et al | 2005 | Maternal mortality among adolescent women in Jos, north-central, Nigeria | Nigeria | A quantitative, retrospective review | 1991–2001 | Girls ages 10–19 | 25 | Abortion was the leading cause of death for 10–19-year-olds (37%) due to unsafe abortion, eclampsia and sepsis. Risk factors for adolescent maternal mortality found in our study were illiteracy, non-utilisation of antenatal services and Hausa/Fulani ethnic group. |

| Ushie, B. A., et al | 2018 | Timing of abortion among adolescent and young women presenting for post-abortion care in Kenya: a cross-sectional analysis of nationally-representative data | Kenya | A quantitative, cross-sectional descriptive study | 2012 | Girls and women ages 12–24 | 1145 | 12–19-year-olds more likely to present for PAC following a second trimester abortion; no other major difference by age. |

Abortion knowledge and attitudes

Five studies in this review examined the knowledge and attitudes of adolescents around the termination of pregnancy. Although adolescents are cognisant of abortion as a service, their knowledge of legality, methods of termination and access points for abortion are low. Among a sample of 10–19-year-old secondary school girls in Lagos, Nigeria, 83% had knowledge of abortion as a topic and 10–14-year-olds were more likely to know legal indications and methods of abortion than those ages 15–19.14 In Ethiopia, 63% of adolescents were aware that abortion is safe in some cases, but few could name the indications for legal abortion.15 An internet survey of students from two technical schools in Brazil showed that the knowledge of abortion methods among 12–14-year-olds was lower than that among 15–16-year-olds (29% vs 40%, respectively).16 Among 16–20-year-old girls in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), 46% knew of a place to obtain an abortion, 71% knew of someone who had had an illegal abortion, and most were able to name at least one health consequence of illegal abortion (death, infertility, infection and bleeding were the most commonly cited).17

Attitudes towards abortion among young adolescents are fairly conservative. In Brazil, legal termination of pregnancy was supported by only 56% of male and female adolescent (12–21-years-old) respondents in a school-based study.16 In Nigeria, younger adolescents (10–14-years-old) were less accepting of abortion than older adolescents (15–19-years-old).14 In a study of 13–19-year-old males and females in Kenya, most participants disagreed with the use of abortion in the case of unwanted pregnancy and girls were significantly more likely to disagree with abortion than boys (91% vs 87%, respectively; p = 0.007)18 In the Democratic Republic of Congo, where at the time of the study abortion was only legal to save a woman’s life, 76% of student respondents (16–20 years) were opposed to illegal abortion.17

Comparative abortion rates/ratios among adolescents vs older groups

Nine studies in this review examined the rates or ratios of abortion among young/very young adolescents compared to older groups of women. In Bangladesh, one study showed a higher abortion ratio among adolescents <18 than 18–19-year-olds (44 vs 23 per 1,000 births, respectively; p < 0.001) and unmarried adolescents were 35 times as likely as married adolescents to abort (20 vs 733 abortions per 1,000 births; p < 0.001).19 In Thailand, the probability of abortion was significantly higher among 10–14-year-olds than among 20–24-year-olds (OR = 1.18, p < 0.001), while in 15–19-year-olds the probability of abortion is reduced (OR = 0.65, p < 0.001).20 In another study in the same setting, Thai girls ages 10–14 had nearly double the ratio of unsafe abortion compared to 15–19-year-olds (1,089 vs 602 unsafe abortions per 100,000 live births, respectively).21 In Brazil, 20% of sexually active 12–14-year-old girls and 27% of 15–19-year-olds reported having had a prior abortion.22 When adjusting for levels of sexual activity in Ethiopia, 15–19-year-old girls had higher rates of legal abortion than any other age group (64%).23 In Nepal, however, women ages 20–34 were significantly more likely to report an induced abortion compared to those under 20 years (OR: 5.54; 95% CI: 2.87–10.72).24

In Malawi, girls ages 10–19 comprised 20–28% of all abortions, second only to the 20–24 age group.25,26 Among all 10–19-year-olds, unmarried adolescents were 11 times as likely to terminate a pregnancy as married girls (p < 0.05) and among all unmarried women, adolescents (10–19 years) had higher rates of abortion (34%) than women aged 20–24 (12%) or women 25+ (20%; p < 0.05).26 In a study in India, the majority of those seeking abortions were under 20 years of age (56%), 38% of whom were girls under the age of 16.27 In Mexico, among 10–14-year-old girls the percentage of all live births ending in abortion rose from 13.6% in 2000 to 16.3% in 2010 while percentages for 15–19-year-old girls remained between 10% and 11% (descriptive abortion rates rose across all other age groups in that same period; however, no significance tests were presented).28

Reasons for abortion

Nine studies solicited reasons why adolescents sought to terminate a pregnancy which included: the desire to continue education or to protect future aspirations; to avoid the stigma of teenage pregnancy; poverty; health; rape; incest or transactional sex.

In Zambia, girls <19 who had induced abortion did so to continue schooling and protect future aspirations.29 These findings were echoed in Bangladesh, Brazil, South Africa and Guadeloupe.19,22,30,31 A study of post-abortion care patients aged less than 19 in Malawi found that 87% were sexually assaulted by someone familiar to them, while another 3% had exchanged sex for money or clothes.18 In South Africa and Zambia adolescents seeking abortion did so due to experiences of sexual violence (i.e. rape or incest); the South African cohort also reported fears of physical trauma due to childbirth as a reason for abortion.30,31 Baba et al., in Japan, also showed that girls 10–14 were more likely to experience pregnancy due to rape or incest than older adolescents.32 In Nigeria, adolescents who had undergone abortion were significantly more likely to have experienced transactional or forced sex.33

Another salient reason for abortion among adolescents was fear of reprisal for getting pregnant outside of marriage or being too young to become a mother, often perpetuated by parents or members of the community. A study of unmarried pregnant adolescents in Uganda found that many girls who sought abortion felt they had to do it to “save face” for their parents; and in some contexts, such as in Mexico, girls reported that parents forced them to seek abortions.28,34 Dahlback et al., in Zambia, and Ramakeula et al., in South Africa, confirmed that girls consider pregnancy shameful and stigmatising for themselves and their families, often leading them to undergo an unsafe abortion.29,30 Poverty and fear for the girls’ maternal health were also important factors in abortion-seeking in a number of contexts including Nigeria and Bangladesh.19,33

Timing of abortion and post-abortion care

Once the decision has been made to terminate a pregnancy, adolescents are more likely to delay the timing of abortion and post-abortion care. The studies with data on the timing of abortion showed that the majority of girls seek abortion in the second trimester and that they are more likely to delay abortion when compared to women in older cohorts.

In a study of girls less than 19 years old in India, 72% sought an abortion in the second trimester.27 Similarly, in Guadeloupe, 55% of adolescents less than 18 years old reported seeking an abortion after nine weeks of amenorrhoea.31 Three studies, in Japan, Ethiopia and Nigeria, showed that when compared to older groups of women, girls younger than 19 were more likely to delay abortion until the second trimester. In Nigeria, 45% of girls ages 10–18 sought a second-trimester abortion compared with 30% of women in older groups.35 In Ethiopia, girls younger than 19 had more than double the odds of aborting in the second trimester, when compared to women aged 25 or older (OR = 2.64% CI: 1.23–5.68).36 In a study of post-abortion care for patients ages 12–19 in Kenya, adolescents were more likely than older women to have undergone a second-trimester abortion.37

Sources and methods of abortion

In the 10 studies that examined sources and methods of care among adolescents, the use of herbal or chemical concoctions or foreign objects inserted in the vagina was common, as was the use of traditional healers.

Ahmed et al., in Bangladesh, showed that 57% of abortion attempts among adolescents were performed by traditional healers (defined as persons in the community who provide treatment for abortion but have no formal training).19 In Zambia, Dahlbeck et al. found that the majority of unsafe abortions (not defined by authors) among adolescents (76%) took place at home, with 47% performed by traditional healers.29 In Cote d’Ivoire adolescents primarily self-prescribe medication (not medical abortion, but rather other over-the-counter medications) (70%) as the first attempt at termination, followed, in case of failure, by traditional healers (56.4%), then healthcare practitioners only at the third attempt (85.7%).38 In Ethiopia, half of the adolescents reported attempting abortion at home while the other half terminated at a health centre.39

Four studies in Brazil, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Zambia reported the unsafe methods used by adolescents for abortion: ingestion of herbs and roots or over-the-counter drugs like Chloroquine, Panadol and Cafernol; foreign objects such as Nescafe, ground glass, or herbs, sticks or leaves inserted into the vagina; and blunt force trauma to the stomach. These methods may have been in the context of a self-induced abortion or one presided over by a traditional healer.16,29,38,40

In Nigeria, lack of access to adequate medical personnel, facilities and equipment were predictors of illegal abortion among girls ages 14–21.41 High cost of safe abortion service fees and distrust in the health care providers were also cited as barriers to accessing safe abortion in Ghana.42

Experiences with formal health care providers

Three studies showed that adolescents experience bias from health care providers and fear their reprisal, which may make them less likely to seek abortion at a formal health care facility. In Ghana, adolescents under the age of 20 (44%) were the least likely to obtain care from trained abortion providers when compared to women ages 20–29 (57%) or women 30 and older (65%).40 When controlling for demographic and economic factors and the knowledge of abortion legality, adolescent girls still had a 77% lower odds of a safe abortion compared to women 30 and older.5 In another study in Ghana, girls perceived providers as being hostile and did not trust providers or facilities to maintain their privacy or confidentiality.40 In Malawi, girls undergoing abortion identified fear of abuse by health providers as one of the main sources of psychological distress during the abortion process.43 In Mexico, adolescent girls who sought abortion care on their own (as opposed to with an accompanying adult) were refused abortion counselling and care.44

Complications of unsafe abortion

Eleven studies in this review addressed the rate and types of complications among adolescent girls undergoing induced abortion, showing that while young adolescents comprise a disproportionate number of unsafe abortions, their risk of complications during abortion as compared to older women is inconclusive.

In Nigeria, adolescents ages 16–20 accounted for 29% of all unsafe abortions (the highest for any age group).45 Two studies in Kenya and Malawi showed that adolescents were between 2 and 3.5 times more likely to experience mechanical injuries due to abortion than women in older groups (significant findings in each case).26,46 In Cote d’Ivoire, complications among adolescents (11–19 years) were significantly associated with either self-induced abortions or abortions performed by traditional healers.38 In Nigeria and South Africa, abortion was a leading cause of death among adolescents under the age of 19.35,41 In Mexico, younger adolescents had a considerably lower rate of hospitalisation due to abortion when compared to older adolescents (0.3 vs 7.6 per 1,000 girls, respectively).28

A South African study of comparative rates of death, or complications due to abortion, found that despite the high rates of abortion among adolescents, adolescents are not at an increased risk of death as compared to women in older groups.47 An analysis of secondary data in Ethiopia also showed no increased risk of complications for 15–19-year-olds compared to older women.23 However, Aung et. Al, in Thailand, found that when compared to older age groups, adolescents ages 10–19 had the highest burden of non-fatal morbidity due to complications from unsafe abortion.21

Psycho-social outcomes of abortion

Five studies in this review touched on the psychosocial outcomes (i.e., depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, etc.) of the abortion process on adolescent girls. In Uganda, Zambia and South Africa, young girls who experienced abortion (specifically unmarried girls) describe facing rejection or denial of paternity by partners during pregnancy, being afraid of bringing shame to their families and fearing stigma from being pregnant out of wedlock. In some cases, particularly among younger adolescents, the pregnancy itself may be a result of rape or incest, which further complicates psychosocial outcomes for girls.29,30,34 In Malawi, girls ages 14–19 reported a great deal of psychological distress prior to abortion due to fear of parents discovering the pregnancy, being forced to leave school, judgement for an out-of-wedlock pregnancy, and abuse from providers, all of which contributed to delay in care-seeking. After the abortion, girls reported feelings of guilt stemming from their religious beliefs and grief around the loss of the child (which they may have kept under better circumstances).43 In Guadeloupe, 43.3% of girls reported psychological problems linked to abortion, mainly due to distress over the deterioration of their relationship with their parents.31

Discussion

This review highlights a number of important areas of abortion care that are specific to adolescents, and some differences between adolescents ages 10–14 and other age cohorts. Results show that girls aged 10–14 differ from older cohorts in that they are less accepting of abortion, they have a higher ratio of abortion (both safe and unsafe), and they are more likely to experience pregnancy leading to abortion as a result of rape or incest than older adolescents. Distinctions in younger versus older adolescent knowledge of abortion legality are not clear, as the two studies in Nigeria and Brazil gave conflicting results in the level of knowledge between the two cohorts.

Adolescents give a number of reasons for seeking an abortion, primary among them being their desire to continue their studies or to protect their future prospects from the burdens of early motherhood. This is particularly true among younger adolescents, many of whom are not married and are still attending school full time. Other common reasons include the shame and stigma of teen pregnancy/motherhood, poverty and pressure from their families. In the case of younger adolescents, the pregnancy is likely due to rape, incest or transactional sex, which further motivates a pregnancy termination. These reflect many of the same reasons that women around the world give for seeking an abortion; the main difference being that older women emphasise limiting childbearing as the main motivation for abortion.48

When compared to older cohorts of women, adolescents consistently tend to delay an abortion into the second trimester, due to fear and shame around the pregnancy, limited knowledge of and access to safe abortion services, delayed recognition of pregnancy status, and fear of health providers. When adolescents do eventually attempt an abortion, the majority try to self-induce with ingested herbal/chemical concoctions or insertion of objects into the vagina, or by seeing traditional healers. Adolescents’ knowledge, resources and mobility to access health care are more limited compared to cohorts of older women; these reasons have been shown to limit general healthcare-seeking behaviour among adolescents, in particular around sexual and reproductive health needs (i.e. contraceptives, antenatal care, etc.), and exacerbate delays in seeking abortion care.49–51

Adolescents cite strong provider bias and lack of privacy and confidentiality by formal health care workers as the main reasons why they do not seek care from formal health providers.52 Studies of providers have shown that they can be judgmental, openly hostile or even deny care to adolescent girls seeking abortions.53,54 Furthermore, providers, even those trained in youth-friendly services, may not be protecting girls’ privacy and confidentiality to the extent necessary. These barriers echo those commonly cited in the context of general adolescent sexual and reproductive health care and point to a pattern of bias against girls seeking any type of sexual health care.55

Although adolescent girls comprise a disproportionate number of women seeking unsafe abortions, they do not necessarily suffer higher rates of complications or maternal mortality than older women. In some of the studies reviewed here, there was evidence of significantly higher rates of mechanical injury (i.e. cut or perforation) among adolescents than among older cohorts, but there were no significant differences in maternal mortality between these groups. However, complications stemming from unsafe abortion are one of the leading causes of death among adolescent girls in LMIC, which may be due to the fact that adolescents tend to delay abortion care until the second trimester.1

There are several limitations to this review, which should be noted when using the results. First, out of the 208 prospective articles, we were only able to locate 131 full-text versions for review due to resource constraints. This may present bias in the findings due to the omission of 77 potential articles. Furthermore, this review examines findings from a variety of LMIC; however, adolescents in each context have unique personal, social or environmental characteristics that determine their abortion experience. While this review provides a global overview of abortion among adolescents, it is not generalisable to all settings.

There are several ways to improve the delivery of care and knowledge to adolescents, particularly 10–14-year-olds. This group is typically still enrolled in school, which provides a promising entry point for education on and access to safe abortion knowledge and services. Although the subject of abortion may be taboo in some contexts, comprehensive sexual education has been shown to have positive outcomes on youth sexual behaviour, including delaying sex and using contraceptives in some countries, both of which could reduce the risk of unsafe abortion.56 As adolescents are subject to parental control, interventions aimed at very young adolescents must recognise the role of the parents in abortion decision-making and work to reduce barriers to communication within the child–parent dyad.57

Pregnancy among 10–14-year-olds is likely due to rape, incest or coerced transactional sex. Implementers and providers must recognise the added trauma of sexual violence that a girl may face and ensure that they are not only receiving adequate and appropriate abortion care but that the underlying sexual violence is also addressed. Trauma-informed care and counselling must also adjust for the fact that for girls, the perpetrator may be her accompanying adult or immediate caregiver.58 Furthermore, even though adolescents are not at greater risk of psychosocial maladjustment following abortion, the event may still be emotionally significant and require sensitive care.59 Providers of abortion care may require more intensive training and patient-centred feedback is needed as part of the follow-up performance improvement loop to overcome biases against adolescent patients.

Conclusions

This review highlights several aspects of abortion programming and policy planning for adolescent girls. Many adolescents lack basic knowledge of puberty or sexual and reproductive health, which increases their chances of missing signs of pregnancy and delaying abortion until the second trimester.5 Sexuality education that is comprehensive and that provides information on puberty and pregnancy, is essential.

Only a handful of the almost 800 studies screened for this paper either focused on or segmented data by adolescents ages 10–14. Researchers should include 10–14-year-olds as a focus of sexual health and abortion studies, examining the types of information and support needed by this group and the most effective ways in which to deliver services, given their unique constellation of issues.

Adolescent girls experience abortion differently than older women and have specific needs for and obstacles to seeking abortion care. By emphasising the unique experiences of these sub-groups of abortion patients, this review may enable programmers and practitioners to build more inclusive, thoughtful and responsive abortion care for the most vulnerable populations around the world.

Footnotes

The authors are fluent in these three languages and included them in the search to maximise inclusion of articles from low- and middle-income countries.

References

- 1.Shah IH, Åhman E.. Unsafe abortion differentials in 2008 by age and developing country region: high burden among young women. Reprod Health Matters. 2012 Jan 1;20(39):169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization.. Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health 2016–2030. Geneva: WHO; 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hindin MJ, Christiansen CS, Ferguson BJ.. Setting research priorities for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . The sexual and reproductive health of young adolescents in developing countries: reviewing the evidence, identifying research gaps, and moving the agenda: report of a WHO technical consultation, Geneva, 4–5 November 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNICEF . Adolescent demographics. October 2019 [cited 2020 Jan]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/demographics/.

- 6.Woog V, Kågesten A.. The sexual and reproductive health needs of very young adolescents aged 10–14 in developing countries: what does the evidence show. New York (NY: ): Guttmacher Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downing J, Bellis MA.. Early pubertal onset and its relationship with sexual risk taking, substance use and anti-social behaviour: a preliminary cross-sectional study. BMC Pub Health. 2009 Dec;9(1):446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierce M, Hardy R.. Commentary: The decreasing age of puberty—as much a psychosocial as biological problem? Int J Epidemiol. 2012 Jan 13;41(1):300–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Population Division, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World marriage patterns, Population Facts, 2016, No. 2016/1. Available from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/ population/publications/pdf/popfacts/PopFacts_2016-1.pdf.

- 10.Abortion Global U. Regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003. World Health Organization. 2008;21.

- 11.Finer L, Fine JB.. Abortion law around the world: progress and pushback. Am J Public Health. 2013 Apr;103(4):585–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Bank . World Bank country and lending groups. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Aug 18;151(4):264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abiola AH, Oke OA, Balogun MR, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of abortion among female students of two public senior secondary schools in Lagos Mainland local government area, Lagos state. Clin Sci. 2016 Apr 1;13(2):82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kebede MM, Bazie BB, Abate GB, et al. Knowledge of abortion legislation among female preparatory school students in Dabat District, Ethiopia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2016;20(4):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell EM, Heumann S, Araujo A, et al. Brazilian adolescents’ knowledge and beliefs about abortion methods: a school-based internet inquiry. BMC Womens Health. 2014 Dec;14(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paluku LJ, Mabuza LH, Maduna PM, et al. Knowledge and attitude of schoolgirls about illegal abortions in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2010;2(1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adaji S, Adaji SE, Warenius LU, et al. The attitudes of Kenyan in-school adolescents toward sexual autonomy. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(1):33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapil Ahmed M, Van Ginneken J, Razzaque A.. Factors associated with adolescent abortion in a rural area of Bangladesh. Trop Med Int Health. 2005 Feb;10(2):198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Areemit R, Thinkhamrop J, Kosuwon P, et al. Adolescent pregnancy: Thailand’s national agenda. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012 Jul 1;95(Suppl 7):S134–S142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aung EE, Liabsuetrakul T, Panichkriangkrai W, et al. Years of healthy life lost due to adverse pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers in Thailand. AIMS Public Health. 2018;5(4):463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Correia DS, Cavalcante JC, Maia E.. Induced abortion: risk factors for adolescent female students, a Brazilian study. Sci. World J. 2009;9:1374–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sully E, Dibaba Y, Fetters T, et al. Playing it safe: legal and clandestine abortions among adolescents in Ethiopia. J Adolesc Health. 2018 Jun 1;62(6):729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehata S, Menzel J, Bhattarai N, et al. Factors associated with induced abortion in Nepal: data from a nationally representative population-based cross-sectional survey. Reprod Health. 2019 Dec;16(1):68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Lema VM. Reproductive awareness behaviour and profiles of adolescent post abortion patients in Blantyre, Malawi. East Afr Med J. 2003;80(7):339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levandowski BA, Pearson E, Lunguzi J, et al. Reproductive health characteristics of young Malawian women seeking post-abortion care. Afr J Reprod Health. 2012;16(2):253–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prabhu TR. Legal abortions in the unmarried women: social issues revisited. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014 Jun 1;64(3):184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiavon R, Troncoso E, Polo G. Increasing abortion-related hospitalization rates among adolescents in Mexico in the last decade, by age group and by state of residence. In: Proceedings of the 15th World Congress on Human R; 2013 Mar 13–16; Venice. Rome: Giornale Italiano di Ostetricia e Ginecologia; 2013. p. 319–323. Available from: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33153592.pdf.

- 29.Dahlbäck E, Maimbolwa M, Yamba CB, et al. Pregnancy loss: spontaneous and induced abortions among young women in Lusaka, Zambia. Cult Health Sex. 2010 Apr 1;12(3):247–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramakuela NJ, Lebese TR, Maputle SM, et al. Views of teenagers on termination of pregnancy at Muyexe high school in Mopani District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2016;8(2):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flory F, Manouana M, Janky E, et al. Sociodemographic and medical features of abortion among underage people in Guadeloupe (French West Indies). Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2014 Apr;42(4):240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baba S, Goto A, Reich MR.. Recent pregnancy trends among early adolescent girls in Japan. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014 Jan 1;40(1):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray N, Winfrey W, Chatterji M, et al. Factors related to induced abortion among young women in Edo state, Nigeria. Stud Fam Plann. 2006 Dec;37(4):251–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atuyambe L, Mirembe F, Johansson A, et al. Experiences of pregnant adolescents-voices from Wakiso district, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2005;5(4):304–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ujah IA, Aisien OA, Mutihir JT, et al. Maternal mortality among adolescent women in Jos, North-Central, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2005 Jan 1;25(1):3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonnen KI, Tuijje DN, Rasch V.. Determinants of first and second trimester induced abortion-results from a cross-sectional study taken place 7 years after abortion law revisions in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014 Dec;14(1):416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ushie BA, Izugbara CO, Mutua MM, et al. Timing of abortion among adolescent and young women presenting for post-abortion care in Kenya: a cross-sectional analysis of nationally-representative data. BMC Women Health. 2018 Dec;18(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aké-Tano SO, Kpebo DO, Konan YE, et al. Abortion practices in high school students in Yamoussoukro. Côte d’Ivoire. Santé Publique. 2017;29(5):711–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bilal SM, Spigt M, Dinant GJ, et al. Utilization of sexual and reproductive health services in Ethiopia – does it affect sexual activity among high school students? Sex Reprod Health. 2015 Mar 1;6(1):14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kyilleh JM, Tabong PT, Konlaan BB.. Adolescents’ reproductive health knowledge, choices and factors affecting reproductive health choices: a qualitative study in the West Gonja District in Northern region, Ghana. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2018 Dec;18(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tunde AI. Socio-economical and sociological factors as predictors of illegal abortion among adolescent in akoko west local government area of ondo state. Nigeria. Pub Health Res. 2013;3(3):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bain LE, Zweekhorst MB, Amoakoh-Coleman M, et al. To keep or not to keep? Decision making in adolescent pregnancies in Jamestown, Ghana. PloS one. 2019;14(9):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chamanga RP, Kazembe A, Maluwa A, et al. Psychological distress among adolescents before during and after unsafe induced abortion in Malawi. J Res Nurs Midwif. 2012 Jul 1;1(2):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clyde J, Bain J, Castagnaro K, et al. Evolving capacity and decision-making in practice: adolescents’ access to legal abortion services in Mexico City. Reprod Health Matters. 2013;21(41):167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akinlusi FM, Rabiu KA, Adewunmi AA, et al. Complicated unsafe abortion in a Nigerian teaching hospital: pattern of morbidity and mortality. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Mar 26;1–6:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gebreselassie H, Gallo MF, Monyo A, et al. The magnitude of abortion complications in Kenya. BJOG. 2005 Sep;112(9):1229–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Wet N. Pregnancy and death: An examination of pregnancy related deaths among adolescents in South Africa. S Afr J Child Health. 2016;10(3):151–155. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bankole A, Singh S, Haas T.. Reasons why women have induced abortions: evidence from 27 countries. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1998 Sep 1;24:117–127. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hock-Long L, Herceg-Baron R, Cassidy AM, et al. Access to adolescent reproductive health services: financial and structural barriers to care. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003 May 1;35(3):144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bright T, Felix L, Kuper H, et al. Systematic review of strategies to increase access to health services among children over five in low-and middle-income countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2018 May;23(5):476–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.World Health Organization (WHO) . Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bankole A, Malarcher S.. Removing barriers to adolescents’ access to contraceptive information and services. Stud Fam Plann. 2010 Jun 1;41(2):117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Izugbara CO, Egesa CP, Kabiru CW, et al. Providers, unmarried young women, and post-abortion care in Kenya. Stud Fam Plann. 2017 Dec;48(4):343–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Håkansson M, Oguttu M, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Human rights versus societal norms: a mixed methods study among healthcare providers on social stigma related to adolescent abortion and contraceptive use in Kisumu, Kenya. BMJ Global Health. 2018;3(2):e000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hobcraft G, Baker T.. Special needs of adolescent and young women in accessing reproductive health: Promoting partnerships between young people and health care providers. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2006 Sep;94(3):350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kirby DB. The impact of abstinence and comprehensive sex and STD/HIV education programs on adolescent sexual behavior. Sex Res Social Policy. 2008 Sep 1;5(3):18. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lederman RP, Chan W, Roberts-Gray C.. Parent—adolescent relationship education (PARE): program delivery to reduce risks for adolescent pregnancy and STDs. Behav Med. 2008 Jan 1;33(4):137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ely GE, Rouland Polmanteer RS, Kotting J.. A trauma-informed social work framework for the abortion seeking experience. Soc Work Ment Health. 2018 Mar 4;16(2):172–200. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pereira J, Pires R, Canavarro MC.. Psychosocial adjustment after induced abortion and its explanatory factors among adolescent and adult women. J Reprod Infant Psych. 2017 Mar 15;35(2):119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]