Abstract

Background:

Histopathological growth patterns (HGPs) of colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) may be an expression of biological tumour behaviour impacting the risk of positive resection margins. The current study aimed to investigate whether non-desmoplastic growth pattern (non-dHGP) is associated with a higher risk of positive resection margins after resection of CRLM.

Methods:

All patients treated surgically for CRLM between January 2000 and March 2015 at the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute and between January 2000 and December 2012 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center were considered for inclusion. Positive resection margin (R1) was defined as tumour cells at the resection margin.

Results:

Of all patients (n=1302) included for analysis, 13% (n=170) had positive resection margins. Factors independently associated with positive resection margins were the non-dHGP (odds ratio (OR): 1.79, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.11-2.87, p=0.016) and a greater number of CRLM (OR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.08-1.23 p<0.001). Both positive resection margins (HR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.13-1.76, p=0.002) and non-dHGP (HR: 1.57, 95% CI: 1.26-1.95, p<0.001) were independently associated with worse overall survival.

Conclusion:

Patients with non-dHGP are at higher risk of positive resection margins. Despite this association, both positive resection margins and non-dHGP are independent prognostic indicators of worse overall survival.

Introduction

Development of colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) is common in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). Over one third of patients are confronted with CRLM at some point in the course of their disease.(1-3) Long term survival and even cure can be achieved by surgical resection in a proportion of selected patients.(4) The ability to accurately predict survival of patients currently remains elusive.(5, 6) One prognostic factor that has been the subject of discussion for many years is the hepatic resection margin. It has been postulated that positive resection margins may be more a reflection of underlying tumour biology rather than surgical technique.(7-9)

CRLM grow in three distinct histopathological growth patterns (HGPs); a desmoplastic (dHGP), a pushing and a replacement type.(10) Recently published international consensus guidelines validated HGPs as a prognostic marker in patients undergoing resection of CRLM and provide a uniform and replicable scoring method.(11) Patients with any observed replacement and/or pushing HGP (taken together as non-dHGP) have worse survival compared to patients with dHGP.(12) We hypothesised that patients with non-dHGP are at higher risk of positive resection margins. The aim of this multicentre cohort study was to investigate a possible association between HGPs and margin status after resection of CRLM, while adequately correcting for potential confounders with sufficient statistical power.

Methods

The current study was approved by the institutional review board of the Erasmus University Medical Center (MEC-2018-1743).

Patients

All consecutive patients who underwent resection of CRLM between January 2000 and March 2015 at the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute (Rotterdam, the Netherlands) and between January 2000 and December 2012 at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, USA) were considered for inclusion. Both institutions are tertiary referral centres for liver surgery. Patients without complete resection of CRLM were excluded. Since resection is a prerequisite for HGP and margin assessment, patients treated solely with ablative therapies were not included in the analyses. When HGP assessment was not possible (e.g. missing or unsuitable tissue slides), the resection margin could not be determined (e.g. extensive thermal damage) or when margin status was not recorded, patients were excluded as well.

Study design, variables and outcomes

Prospectively maintained databases were used to extract patient demographics, clinicopathological data, treatment details and survival data. One of the variables that was extracted was the Clinical Risk Score (CRS) and its determinants.(13) Hepatic arterial infusion pump (HAIP) chemotherapy combined with systemic chemotherapy was administered to a proportion of the MSKCC patients pre- and or postoperatively as described previously.(14) Positive resection margin (R1) was defined as tumour cells at the resection margin. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time in months from the date of CRLM resection until the date of death. When alive, patients were censored at date of last follow-up. As preoperative chemotherapy might influence the risk of positive resection margins, a distinction was made between preoperative systemic chemotherapy without HAIP and preoperative HAIP chemotherapy when investigating possible predictors of R1 resection margins. For survival analyses, a distinction was made between any perioperative systemic chemotherapy without HAIP (i.e. pre- and/or postoperative systemic chemotherapy without HAIP) and any perioperative HAIP chemotherapy (i.e. pre- and/or postoperative HAIP chemotherapy) to correct for the possible prognostic effect of perioperative chemotherapy.

Pathological assessment of HGPs and resection margins

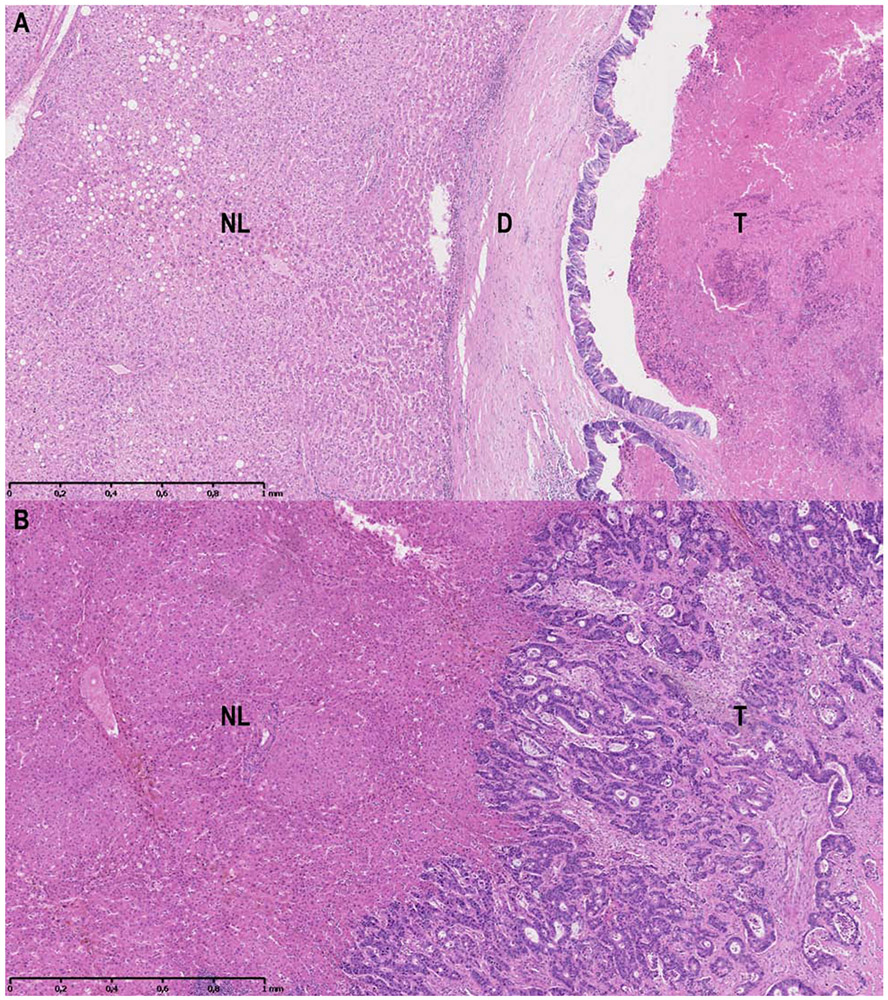

Since the first description of HGPs(10), multiple studies have shown their prognostic value.(15-19) Recently, international consensus guidelines for HGP assessment defined a uniform and replicable scoring system.(11) In order to retrospectively determine the HGPs of all patients at both centres, a per patient re-evaluation was performed of all available haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of all resected CRLM from all patients by means of light microscopy. At the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute the HGP assessment for the current study was performed by a dedicated HGP pathologist (PV) and researchers (PN, DH, ES, BG) trained by the dedicated HGP pathologist according to these guidelines. At the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center the HGPs were subsequently scored in a similar manner according to the same guidelines by one of the trained researchers (ES) and for difficult cases the dedicated HGP pathologist (PV) was consulted. The currently applied methodology has recently been validated in a previous study regarding the diagnostic accuracy of HGP determination.(20) Interobserver agreement (expressed in Cohen’s k) compared to the gold standard was determined for a researcher without experience in HGP assessment. After two training sessions the interobserver agreement for the researcher compared to the gold standard was excellent (k=0.951). The scoring of HGPs was performed with the observers blinded to all patient characteristics and outcome. The entire interface between the tumour border and normal liver parenchyma was evaluated. Every fraction of the tumour-liver interface, accounting for 5% or more of the total interface, was taken into account. In the consensus guidelines a cut-off value of 50% is used for determining the predominant HGP, but new insights with regard to this cut-off value have emerged. The presence of any non-dHGP, rather than the percentage, dictates prognosis.(12) Tumours displaying only dHGP were therefore classified as dHGP and tumours displaying any HGP other than dHGP were categorised as non-dHGP. Examples of dHGP (figure 1A) and non-dHGP (figure 1B) are displayed in figure 1. Tissue sections were considered unsuitable for HGP assessment when less than 20% of the tumour/liver interface was available, when the quality of the H&E tissue section was insufficient or when viable tumour tissue was absent.(11)

Figure 1A-B.

1A: Example of the dHGP. 1B: Example of the non-dHGP. Abbreviations: NL: normal liver; D: desmoplastic stroma; T: tumour core.

Histopathological assessment of the resection margin was executed by the pathologists of both respective institutions. In the case of multiple CRLM, the closest resection margin is reported as the final resection margin.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented using absolute numbers with percentages and continuous data using medians with corresponding interquartile range (IQR). Differences in proportions were evaluated using the Chi-squared test. Medians were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test. Estimated median follow-up time for survivors was obtained using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. Survival estimates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival estimates were computed until 60 months and were compared using the log-rank test. Uni- and multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate factors associated with R1 resection and factors associated with non-dHGP. Variables entered in the logistic regression model for positive margins were lymph node positivity of the primary tumour, the disease free interval between resection of the primary tumour and diagnosis of CRLM, number of CRLM, size of the largest CRLM, preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, preoperative systemic and/or HAIP chemotherapy, known extra hepatic disease and HGP. Variables entered in the logistic regression model for any presence of non-dHGP were identical. Preoperative systemic and/or HAIP chemotherapy was included in the model due to the different proportional distribution of HGPs observed in patients treated with preoperative chemotherapy compared to chemonaive patients.(12) Logistic regression results were displayed using odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). To assess the prognostic value for OS, uni- and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed. Potential multicollinearity in our Cox regression model was evaluated using the variance inflation factor (VIF).(21) The VIFs for all variables in the multivariable Cox regression were determined. A VIF below 4 indicates that no multicollinearity affecting the model exist, but should ideally be close to 1.(22) Proportional hazards regression results were displayed using hazard ratios (HR) and corresponding 95% CI. Statistical significance was defined as α < 0.05. No imputation of missing data was applied. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and R version 3.5.1 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Patient characteristics

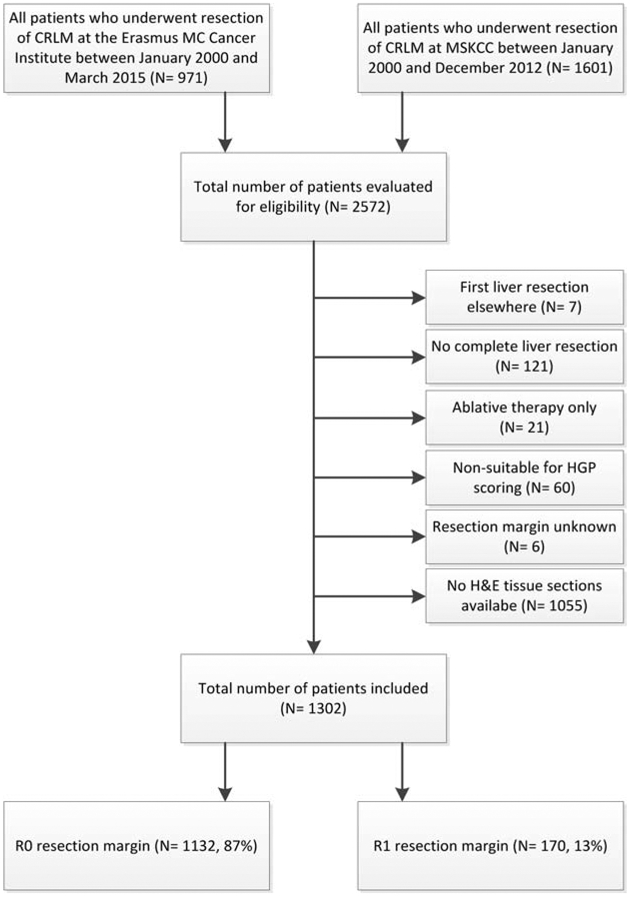

At the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, a total of 971 patients underwent resection of CRLM between January 2000 – March 2015 and were evaluated for inclusion. At the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1601 patients underwent resection of CRLM between January 2000 – December 2012 and were considered for eligibility. In total 1270 patients (49%) were excluded. The most common reason for exclusion was unavailability of H&E tissue sections (n=1055, 83%). A total of 1302 patients were included for analysis, of whom 170 (13%) had positive resection margins (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of patient inclusion.

Non-dHGP versus dHGP

Baseline characteristics stratified by HGP are presented in supplementary table 1. Patients with non-dHGP had a higher proportion of lymph node positive primary tumours (62% versus 55%, p=0.039), a longer disease free interval (median 2 versus 0 months, p<0.001), larger CRLM (median 3.1 versus 2.5 cm, p<0.001) and higher preoperative CEA levels (median 14.3 versus 6.9 μg/L, p<0.001). The proportion of R1 resection margins was higher in the non-dHGP group (14% vs. 9%, p=0.007). Patients with non-dHGP less often received preoperative systemic chemotherapy without HAIP (54% versus 63%, p=0.004), less often received HAIP chemotherapy preoperatively (2% versus 5%, p=0.008) and less often received any perioperative HAIP chemotherapy (16% versus 21%, p=0.046).

On multivariable logistic regression analysis a node positive primary (OR [95%CI]: 1.53 [1.15-2.03], p=0.003) and larger CRLM (1.13 [1.06-1.20], p<0.001) were independently associated with a higher chance of non-dHGP, whereas preoperative systemic chemotherapy (0.54 [0.39-0.74], p<0.001) and preoperative HAIP chemotherapy (0.30 [0.15-0.62], p=0.001) were independently associated with a lower chance of finding non-dHGP on H&E tissue sections (supplementary table 2).

R0 versus R1 resection

Baseline characteristics stratified by resection margin status are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by resection margin status

| Total (N= 1302) |

R0 resection (N= 1132, 87%) |

R1 resection (N= 170, 13%) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 790 (60.7%) | 685 (60.5%) | 105 (61.8%) | 0.755 |

| Female | 512 (39.3%) | 447 (39.5%) | 65 (38.2%) | ||

| Age | Median (IQR) | 63 (55-71) | 64 (55-71) | 62 (55-67) | 0.047* |

| Primary tumour | |||||

| Nodal status | N0 | 503 (39.9%) | 442 (40.2%) | 61 (37.4%) | 0.496 |

| N+ | 759 (60.1%) | 657 (59.8%) | 102 (62.6%) | ||

| Missing | 40 patients | ||||

| CRLM | |||||

| DFI in months | Median (IQR) | 0 (0-17) | 0 (0-17) | 0 (0-15) | 0.277 |

| Missing | 23 patients | ||||

| Number of CRLM | Median (IQR) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-3) | 3 (2-5) | <0.001* |

| Size of largest CRLM | Median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0-4.7) | 3.0 (2.0-4.5) | 3.3 (2.3-4.0) | 0.028* |

| Missing | 4 patients | ||||

| Preoperative CEA (μg/L) | Median (IQR) | 12.0 (4.4-40.8) | 12.0 (4.4-35.5) | 14.2 (4.3-58.0) | 0.063 |

| Missing | 66 patients | ||||

| CRS | Low | 749 (60.8%) | 674 (62.6%) | 75 (48.1%) | <0.001* |

| High | 483 (39.2%) | 402 (37.4%) | 81 (51.9%) | ||

| Incomplete CRS | 70 patients | ||||

| Preoperative systemic CTx without HAIP | No | 575 (44.2%) | 515 (45.5%) | 60 (35.3%) | 0.012* |

| Yes | 726 (55.8%) | 616 (54.5%) | 110 (64.7%) | ||

| Missing | 1 patient | ||||

| Preoperative HAIP CTx | No | 1263 (97.0%) | 1101 (97.3%) | 162 (95.3%) | 0.161 |

| Yes | 39 (3.0%) | 31 (2.7%) | 8 (4.7%) | ||

| Any perioperative systemic CTx without HAIP | No | 622 (47.8%) | 549 (48.5%) | 73 (42.9%) | 0.173 |

| Yes | 679 (52.2%) | 582 (51.5%) | 97 (57.1%) | ||

| Missing | 1 patient | ||||

| Any perioperative HAIP CTx | No | 1078 (82.8%) | 937 (82.8%) | 141 (82.9%) | 0.957 |

| Yes | 224 (17.2%) | 195 (17.2%) | 29 (17.1%) | ||

| Extra Hepatic Disease | No | 1138 (87.4%) | 985 (87.0%) | 153 (90.0%) | 0.274 |

| Yes | 164 (12.6%) | 147 (13.0%) | 17 (10.0%) | ||

| HGP | Non-dHGP | 997 (76.6%) | 853 (75.4%) | 144 (84.7%) | 0.007* |

| dHGP | 305 (23.4%) | 279 (24.6%) | 26 (15.3%) |

Abbreviations in alphabetical order: CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; CRLM: colorectal liver metastases; CRS: clinical risk score; CTx: chemotherapy; DFI: disease free interval; dHGP: desmoplastic HGP; EMC: Erasmus Medical Centre; HAIP: hepatic arterial infusion pump; HGP: histopathological growth pattern; IQR: interquartile range; MSKCC: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; N0: lymph node negative primary tumour; N+: lymph node positive primary tumour; non-dHGP: non desmoplastic HGP; R0: negative resection margin R1: positive resection margin

indicates significant P-value

The results of the uni- and multivariable logistic regression models on the presence of R1 resection are reported in table 2. Any observed non-dHGP (OR [95%CI]: 1.79 [1.11-2.87], p=0.016) and the number of CRLM (1.15 [1.08-1.23], p<0.001) were independently associated with a greater risk of an R1 resection.

Table 2.

Uni- and multivariable Logistic regression analysis of factors potentially associated with an R1 resection margin

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | P-value | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | P-value |

| Node positive primary | 1.125 [0.801-1.579] | 0.497 | 1.072 [0.742-1.550] | 0.710 |

| DFI (cont.) | 0.992 [0.982-1.002] | 0.122 | 0.997 [0.986-1.009] | 0.629 |

| Number of CRLM (cont.) | 1.189 [1.121-1.262] | <0.001* | 1.153 [1.077-1.234] | <0.001* |

| Size CRLM (cont.) | 1.043 [0.987-1.103] | 0.131 | 1.043 [0.980-1.111] | 0.184 |

| Preoperative CEA (cont.) | 1.000 [1.000-1.000] | 0.939 | 1.000 [1.000-1.000] | 0.744 |

| Preoperative systemic CTx without HAIP | 1.533 [1.096-2.144] | 0.013* | 1.202 [0.799-1.809] | 0.376 |

| Preoperative HAIP CTx | 1.754 [0.792-3.882] | 0.166 | 2.099 [0.863-5.105] | 0.102 |

| Extra hepatic disease | 0.745 [0.438-1.265] | 0.275 | 0.704 [0.395-1.254] | 0.233 |

| Non-dHGP | 1.812 [1.168-2.810] | 0.008* | 1.787 [1.112-2.871] | 0.016* |

Abbreviations in alphabetical order: CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; CI: confidence interval; CRLM: colorectal liver metastases; CTx: chemotherapy; DFI: disease free interval; HAIP: hepatic arterial infusion pump; HGP: histopathological growth pattern; non-dHGP: non-desmoplastic HGP; R1: positive resection margin

indicates significant P-value

Survival and resection margin in the context of HGPs

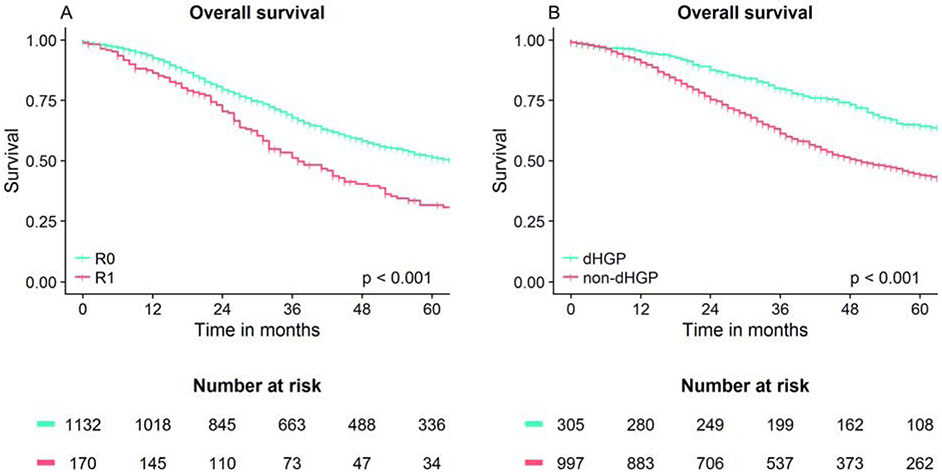

The median follow-up for survivors was 66 months (IQR: 46-100 months). During follow-up 677 patients (52%) died. The median OS of the total group was 58 months (IQR: 27-151). With an R0 resection, patients had a median OS of 64 months (IQR: 29-170), compared to a median of 37 months (IQR: 22-80) when an R1 resection was performed (overall log-rank: p<0.001, figure 3A). Median OS of patients with non-dHGP was 50 months (IQR: 25-114), while the median OS of patients dHGP was 80 months (IQR: 46-Not reached) (overall log-rank: p<0.001, figure 3B).

Fig. 3A-B.

Overall survival curves.

The results of the uni- and multivariable Cox regression analysis for OS are reported in table 3. All VIFs (data not shown) were below 1.5 indicating that there is no evidence of multicollinearity. After correction for well known risk factors and perioperative chemotherapy treatment strategy both R1 resection (HR [95%CI]: 1.41 [1.13-1.76], p=0.002) and non-dHGP (1.57 [1.26-1.95], p<0.001) remained independently associated with worse OS. supplementary tables 3 and 4 display the uni- and multivariable Cox regression analyses for OS in patients with an R0 and an R1 resection margin, respectively.

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis Overall Survival total group

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazard Ratio [95% CI] | P-value | Hazard Ratio [95% CI] | P-value |

| Age at resection (cont.) | 1.013 [1.006-1.019] | <0.001* | 1.016 [1.008-1.023] | <0.001* |

| Node positive primary | 1.464 [1.245-1.721] | <0.001* | 1.455 [1.226-1.728] | <0.001* |

| DFI (cont.) | 1.001 [0.997-1.005] | 0.698 | 0.997 [0.993-1.002] | 0.221 |

| Number of CRLM (cont.) | 1.055 [1.022-1.089] | 0.001* | 1.078 [1.039-1.118] | <0.001* |

| Size CRLM (cont.) | 1.050 [1.027-1.074] | <0.001* | 1.063 [1.035-1.091] | <0.001* |

| Preoperative CEA (cont.) | 1.000 [1.000-1.000] | 0.483 | 1.000 [1.000-1.000] | 0.898 |

| Any perioperative systemic CTx without HAIP | 1.229 [1.056-1.430] | 0.008* | 0.788 [0.650-0.954] | 0.015* |

| Any perioperative HAIP CTx | 0.575 [0.460-0.719] | <0.001* | 0.542 [0.413-0.710] | <0.001* |

| R1 resection CRLM | 1.615 [1.316-1.981] | <0.001* | 1.409 [1.129-1.759] | 0.002* |

| Extrahepatic disease | 1.784 [1.448-2.196] | <0.001* | 1.731 [1.378-2.174] | <0.001* |

| Non-dHGP | 1.814 [1.480-2.223] | <0.001* | 1.569 [1.261-1.951] | <0.001* |

Abbreviations in alphabetical order: CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; CI: confidence interval; CRLM: colorectal liver metastases; CTx: chemotherapy; DFI: disease free interval; HAIP: hepatic arterial infusion pump; HGP: histopathological growth pattern; non-dHGP: non-desmoplastic HGP; R1: positive resection margin

indicates significant P-value

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that the presence of any non-dHGP is independently associated with a higher incidence of positive resection margins in patients with resectable CRLM. In addition, an increasing number of CRLM is also independently associated with a higher risk of an R1 resection. These findings suggest that both technical aspects of the liver resection (e.g. the number of CRLM) and biology may play a role together in the obtainment of an R1 resection. Positive resection margins remain associated with worse survival in the context of HGPs.

It has been argued that the occurrence of positive resection margins may be a reflection of underlying tumour biology.(7-9) One of the potential explanations that has been suggested is the HGP.(7) The proposition that non-dHGP may put patients at a higher risk of positive resection margins is strengthened by the current report and recent literature. Brunner et al.(15) reported a decreased R1 resection rate among patients with “encapsulated” CRLM when compared to patients with “non-encapsulated” CRLM. Nearly three quarters of patients with an R1 resection displayed non-encapsulated CRLM. When one reviews the photographs of the H&E tissue sections presented in their paper, it appears that what the authors designate as “encapsulated” and “non-encapsulated” CRLM, may correspond respectively with dHGP and non-dHGP described by us and others.(10, 11) In that study, of the 121 only twenty patients (17%) with an R1 resection were observed and the ability to draw solid conclusions was limited. In the current study, 170 of the 1302 (13%) resected patients had an R1 resection, providing sufficient power to adequately correct for potential confounders. Increasing number of CRLM was also associated with greater risk of an R1 resection and is concordant with previous studies.(8, 23, 24) In addition, non-HGP was associated with positive margins, but R1 resections were also seen in patients with dHGP, suggesting that both technique and biology may play an important role in R1 resection margins.

Few small subsets of patients are known in whom resection margins hold no prognostic value after resection of CRLM.(9, 25-27) Patients with CRLM displaying non-dHGP had worse prognosis after resection of CRLM. This finding is in line with previous studies.(11, 12, 15, 17-19) With regard to the prognostic value of margin status there has been much debate. There are some studies that found no negative prognostic value of positive margins.(27) This lack of prognostic value of positive margins was also found by others: in patients with low or moderate disease burden(9, 28), in the era of modern systemic chemotherapy(9, 26) and in case of a good pathological response.(25) Although extensively studied and different definitions of a positive margin are handled in recent literature, most studies show a negative association of positive margins and survival after resection of CRLM.(8, 23, 25, 29, 30) The aforementioned illustrates that the prognostic value of both HGPs and positive margins have been reported before separately, but not within the scope of a single study. In the current study, after correction for the HGP and other clinicopathological variables, positive resection margins remained negatively associated with OS.

Subgroup analyses in the patients with an R1 resection showed that only the size of the largest CRLM was independently associated with worse survival. Interestingly, HAIP chemotherapy was not associated with improved survival in the R1 resection subgroup, whereas this was the strongest predictor for improved outcome in the R0 resection subgroup. This is in line with a previous propensity score matched cohort study that found no association between HAIP chemotherapy and improved survival in patients with an R1 resection.(31)

This is the first study to demonstrate a significant association between the HGP and the incidence of positive resection margins when correcting for potential confounders. As both the HGP and the resection margin are determined postoperatively, these findings are currently of little clinical relevance. This further underlines the urgent need for preoperative HGP assessment methods. Preoperative knowledge on the HGP could allow tailor-made (surgical) treatment strategies such as preoperative chemotherapy or wider resection margins in the case of non-dHGP CRLM. Several diagnostic tools are currently investigated for pre-operative HGP assessment. Examples include computational radiomics(32) and liquid biopsies (circulating tumour cells and cell-free DNA).(33-35) Future research should focus on finding a (non-invasive) preoperative surrogate marker for HGPs.

Limitations of the current study should be taken into account. HGP assessment was performed retrospectively. In 1052 potentially eligible patients no H&E tissue sections were available for HGP determination. This could have induced selection bias. Although the current study describes a fairly large number of patients with an R1 resection, subgroup analyses in 170 patients with an R1 resection might be prone to a type II statistical error. Another shortcoming of this study is the unavailability of (RAS) mutational status. The presence of RAS mutations has been associated with a higher chance of positive resection margins by Brudvik and colleagues using a definition of a <1 mm for positive resection margins.(36) The results of this study should be interpreted with caution due to sample size limitations (only 48 patients had a positive margin).

In conclusion both the presence of any non-dHGP and the number of CRLM are associated with a higher rate of positive resection margins. This suggests that not only technical aspects of the resection but also underlying tumour biology may influence the risk of a positive margin at hepatic resection for CRLM. Importantly, both positive resection margins and non-dHGP remain prognostic indicators for worse overall survival when taking both into consideration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Previous communication: The preliminary results of the current study have been presented by means of an oral presentation at the IHPBA conference at Geneva in September 2018.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Elferink MA, de Jong KP, Klaase JM, Siemerink EJ, de Wilt JH. Metachronous metastases from colorectal cancer: a population-based study in North-East Netherlands. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(2):205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, Coatmeur O, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Epidemiology and Management of Liver Metastases From Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg. 2006;244(2):254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Geest LG, Lam-Boer J, Koopman M, Verhoef C, Elferink MA, de Wilt JH. Nationwide trends in incidence, treatment and survival of colorectal cancer patients with synchronous metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2015;32(5):457–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson JS, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Kornprat P, Gonen M, et al. Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases defines cure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4575–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanas GP, Taylor A, Primrose JN, Langeberg WJ, Kelsh MA, Mowat FS, et al. Survival after liver resection in metastatic colorectal cancer: review and meta-analysis of prognostic factors. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:283–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts KJ, White A, Cockbain A, Hodson J, Hidalgo E, Toogood GJ, et al. Performance of prognostic scores in predicting long-term outcome following resection of colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2014;101(7):856–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Angelica MI. Positive Margins After Resection of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer in the Liver: Back to the Drawing Board? Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(9):2432–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadot E, Groot Koerkamp B, Leal JN, Shia J, Gonen M, Allen PJ, et al. Resection margin and survival in 2368 patients undergoing hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: surgical technique or biologic surrogate? Ann Surg. 2015;262(3):476–85; discussion 83-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truant S, Sequier C, Leteurtre E, Boleslawski E, Elamrani M, Huet G, et al. Tumour biology of colorectal liver metastasis is a more important factor in survival than surgical margin clearance in the era of modern chemotherapy regimens. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17(2):176–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermeulen PB, Colpaert C, Salgado R, Royers R, Hellemans H, Van Den Heuvel E, et al. Liver metastases from colorectal adenocarcinomas grow in three patterns with different angiogenesis and desmoplasia. J Pathol. 2001;195(3):336–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dam PJ, van der Stok EP, Teuwen LA, Van den Eynden GG, Illemann M, Frentzas S, et al. International consensus guidelines for scoring the histopathological growth patterns of liver metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(10):1427–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galjart B, Nierop PMH, van der Stok EP, van den Braak R, Hoppener DJ, Daelemans S, et al. Angiogenic desmoplastic histopathological growth pattern as a prognostic marker of good outcome in patients with colorectal liver metastases. Angiogenesis. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230(3):309–18; discussion 18-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kemeny N, Huang Y, Cohen AM, Shi W, Conti JA, Brennan MF, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of chemotherapy after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(27):2039–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunner SM, Kesselring R, Rubner C, Martin M, Jeiter T, Boerner T, et al. Prognosis according to histochemical analysis of liver metastases removed at liver resection. Br J Surg. 2014;101(13):1681–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eefsen RL, Vermeulen PB, Christensen IJ, Laerum OD, Mogensen MB, Rolff HC, et al. Growth pattern of colorectal liver metastasis as a marker of recurrence risk. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2015;32(4):369–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frentzas S, Simoneau E, Bridgeman VL, Vermeulen PB, Foo S, Kostaras E, et al. Vessel co-option mediates resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy in liver metastases. Nat Med. 2016;22(11):1294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen K, Rolff HC, Eefsen RL, Vainer B. The morphological growth patterns of colorectal liver metastases are prognostic for overall survival. Mod Pathol. 2014;27(12):1641–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siriwardana PN, Luong TV, Watkins J, Turley H, Ghazaley M, Gatter K, et al. Biological and Prognostic Significance of the Morphological Types and Vascular Patterns in Colorectal Liver Metastases (CRLM): Looking Beyond the Tumor Margin. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(8):e2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoppener DJ, Nierop PMH, Herpel E, Rahbari NN, Doukas M, Vermeulen PB, et al. Histopathological growth patterns of colorectal liver metastasis exhibit little heterogeneity and can be determined with a high diagnostic accuracy. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kutner M, Nachtsheim C, Neter J. Applied Linear Statistical Models. 4th ed: McGraw-Hill/Irwin; 2004. 408–10 p. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miles J, Shevlin M. Applying regression & correlation: a guide for students and researchers: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Are C, Gonen M, Zazzali K, Dematteo RP, Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, et al. The impact of margins on outcome after hepatic resection for colorectal metastasis. Ann Surg. 2007;246(2):295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh FK, Tekkis PP, O'Rourke T, John TG, Rees M. Quantification of risk of a positive (R1) resection margin following hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: an aid to clinical decision-making. Surg Oncol. 2008;17(1):3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andreou A, Aloia TA, Brouquet A, Dickson PV, Zimmitti G, Maru DM, et al. Margin status remains an important determinant of survival after surgical resection of colorectal liver metastases in the era of modern chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 2013;257(6):1079–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayez N, Lalmahomed ZS, Eggermont AM, Ijzermans JN, de Jonge J, van Montfort K, et al. Outcome of microscopic incomplete resection (R1) of colorectal liver metastases in the era of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(5):1618–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodingbauer M, Tamandl D, Schmid K, Plank C, Schima W, Gruenberger T. Size of surgical margin does not influence recurrence rates after curative liver resection for colorectal cancer liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2007;94(9):1133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez D, Morris-Stiff G, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP, Prasad KR. Interaction of tumour biology and tumour burden in determining outcome after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12(2):84–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamady ZZ, Lodge JP, Welsh FK, Toogood GJ, White A, John T, et al. One-millimeter cancer-free margin is curative for colorectal liver metastases: a propensity score case-match approach. Ann Surg. 2014;259(3):543–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margonis GA, Sergentanis TN, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Andreatos N, Tzanninis IG, Sasaki K, et al. Impact of Surgical Margin Width on Recurrence and Overall Survival Following R0 Hepatic Resection of Colorectal Metastases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groot Koerkamp B, Sadot E, Kemeny NE, Gonen M, Leal JN, Allen PJ, et al. Perioperative Hepatic Arterial Infusion Pump Chemotherapy Is Associated With Longer Survival After Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Propensity Score Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(17):1938–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, Parmar C, Grossmann P, Carvalho S, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lalmahomed ZS, Mostert B, Onstenk W, Kraan J, Ayez N, Gratama JW, et al. Prognostic value of circulating tumour cells for early recurrence after resection of colorectal liver metastases. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(3):556–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mostert B, Sieuwerts AM, Bolt-de Vries J, Kraan J, Lalmahomed Z, van Galen A, et al. mRNA expression profiles in circulating tumor cells of metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Mol Oncol. 2015;9(4):920–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onstenk W, Sieuwerts AM, Mostert B, Lalmahomed Z, Bolt-de Vries JB, van Galen A, et al. Molecular characteristics of circulating tumor cells resemble the liver metastasis more closely than the primary tumor in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(37):59058–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brudvik KW, Mise Y, Chung MH, Chun YS, Kopetz SE, Passot G, et al. RAS Mutation Predicts Positive Resection Margins and Narrower Resection Margins in Patients Undergoing Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(8):2635–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.