Abstract

It is often difficult for people with cancer to make decisions for their care. The aim of this review is to understand the importance of shared decisionmaking (SDM) in Indian clinical scenario and identify the gaps when compared to practices in the Western world. A systematic search (2000-2019) was executed in Medline and Google Scholar using predefined keywords. Of the approximate 400 articles retrieved, 43 articles (Indian: 5; Western: 38) were selected for literature review. Literature review revealed the paucity of information on SDM in India compared to the Western world data. This may contribute to patientreported physical or psychological harms, life disruptions, or unnecessary financial costs. Western world data demonstrate the involvement and sharing of information by both patient and physician, collective efforts of the two to build consensus for preferred treatment. In India, involvement of patients in the planning for treatment is largely limited to tertiary care centers, academic institutes, or only when the cost of therapy is high. In addition, cultural beliefs and prejudices impact the extent of participation and engagement of a patient in disease management. Communication failures have been found to strongly correlate with the medicolegal malpractice litigations. Research is needed to explore ways to how to incorporate SDM into routine oncology practice. India has a high unmet need towards SDM in diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Physicians need to involve patients or their immediate family members in decision making, to make it a patient-centric approach as well. SDM enforces to avoid uninformed decisionmaking or a lack of trust in the treating physician's knowledge and skills. Physician and patient education, development of tools and guiding policies, widespread implementation, and periodic assessments may advance the practice of SDM.

Keywords: Cancer care, patient empowerment, patient engagement, patient-centered care, shared decision-making

INTRODUCTION

Background: What is shared decision-making

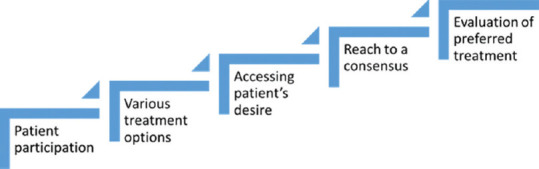

Considering the life-threatening course of cancer and its emotional impact, sometimes, it is difficult for patients to identify the most suitable treatment for them. Shared decision-making (SDM) is an evolving practice in medical care, and one of the several models discussed during patient treatment. SDM is a key component to health-care policies and is being increasingly adopted by physicians, patients, and policymakers. The key characteristics of SDM include involvement of both physician and patient, sharing of information by both patient and physician, collective efforts of the two to build consensus for preferred treatment, and mutual agreement for the planned treatment and its implementation.[1] Figure 1 shows the involvement of both patient and physician to mutually build a consensus preferred treatment. The positive outcomes, virtue, and ethical essence of patient-centered care reinforce the need for SDM and integration of the same in health-care practices.[2]

Figure 1.

Correlationship between patient and physician to build a consensus

People facing serious illnesses such as cancer have a great stake in the decision-making process. Cancer treatment can result in toxicity and lifestyle disruptions.[3] Patients are at the center of the framework of patient-centered care, which conveys the most important goal of a high-quality cancer care delivery system: meeting the needs of patients with cancer and their families. Such a system should support all patients and families in making informed health-care decisions that are consistent with their needs, values, and preferences.[4]

Over the last decade, SDM has been gaining trends in many countries. In the USA, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act supports the patient-centered medical home models of care to strengthen the primary health-care system in the country. In the UK, the National Health Services has emphasized upon the importance of SDM in health care and has enabled access to patient decision-making aids. Patients are being informed and physicians are being trained for collaborative planning for care and treatment.[5] The Norwegian government gives the highest priority to health-care system, where a national health portal is in function, having corresponding guidelines for a standard patient pathway. Similar “Patient Rights Acts” is in use in Germany where informed decisions, comprehensible information for patients, and decisions based on a clinician–patient partnership are enforced.[6] The Governments of the Netherlands, Spain, and Italy have considered patient's right as a legal system and implementing the SDM in their corresponding health-care systems.

In India, implementation of SDM is a challenge, knowing the cultural and behavioral differences existing between patient, the immediate family members, and physicians. In this review, our aim is to identify the gaps existing between Indian and Western world data on SDM and steps to bridge the gap between the two.

METHODS

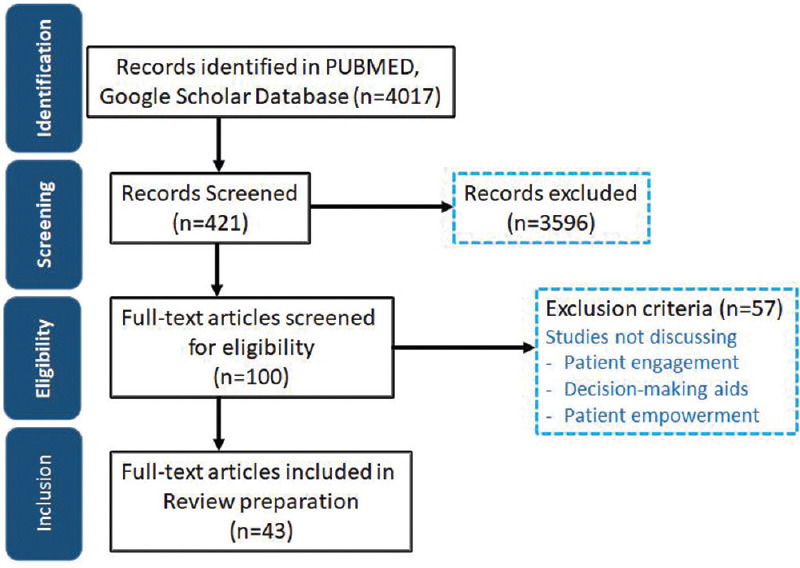

The PRISMA guidelines for meta-analyses were adopted for a study that was conducted in accordance with a predetermined, nonregistered protocol. We performed an extensive literature PubMed and the Google Scholar library database for articles published between 2000 and December 2019. In addition, we checked the reference lists of the reviews available for authentication as well. Figure 2 describes the details of the PRISMA flow and article selection. We included articles reporting search terms “Shared decision making,” “Patient engagement,” and “Patient empowerment.” The search results were first screened for relevance. After reviewing, appropriate articles were considered for study inclusion, and the data were extracted. A total of 421 articles were retrieved, and these were further shortlisted for patient engagement, decision-making aids, and patient empowerment. Out of 100 articles shortlisted, full texts of 43 articles were selected for this review after excluding the duplicates (India: 5; Western world: 38) by using predefined criteria. The data on SDM in Western world and India were compared, gaps were identified, and possible future strategy was discussed.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the study selection process

RESULTS

Choice of decision-making: Western world data

The growing focus on patient-centered oncology care is increasing the demand on physicians' time and effort to engage patients and their families in treatment decision-making. Western world data demonstrate that there is an increasing participation of patients in the decision-making for the management of disease. Patient decision roles and preferences were evaluated in a systematic review of 115 studies from 1980 to 2007.[7] The authors reported patient preferences for shared decisions in most patients, in 63% of the studies. Majority of the patients preferred sharing decision roles in 71% of the studies from 2000 and later compared to only 50% of studies dated before 2000.

Oncologists are increasingly making efforts to integrate with patients and their families to help them with treatment decisions. Multiple effective therapies, the complex interplay between benefits and risks, compliance with treatment recommendations based on evidence, and access to an affordable option complicate the planning and implementation of chemotherapy in cancer patients.[8] In an interview-guided survey on patients from a Canadian ambulatory oncology program who were undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy (RT), or both, for cancer, of the 192 participants, 98 (51%) perceived that they were offered treatment choices for their cancer treatment. When offered choices, patients were more active in decision-making.[3]

The desire and extent for participation in treatment planning has been found to vary according to age, educational status, disease severity, and cultural background. People's preferences may vary according to the stage in the course of a disease episode and the severity of their condition. Every patient is unique in their own views, values, preferences, and life circumstances. This has a strong bearing on the choices they make when it comes to choosing an appropriate treatment for their condition. Patients may be attracted to use a newer treatment option, but their understating of the safety and dosing objectives may remain suboptimal. Any uncertainty of benefit, likely adverse effects, and estimated prognosis should be clearly communicated and understood by the patients before any decisions are made for proceeding to treatment.[9] Hence, it is not just a question of clinical effectiveness, but of balancing the potential benefits and harms of different available options to find what is most appropriate for the individual, and sometimes clinical practice guidelines not that effective in communication with patients.[10]

Decision aids or tools designed to help people participate in decision-making about health care options are also being applied, to help patients with advanced cancer plan and choose and implement the required chemotherapy. One recent study shows the involvement of patients based on the questionnaire for SDM in a oncology setting.[11] The decision aids were reported to be associated with stronger treatment preferences and increased subjective knowledge. Though decision aids only marginally improved the decision-making process, patient well-being was not adversely impacted due to their application.[12]

Research has demonstrated that two-way communication, shared understanding, and trust between patients and health-care providers are paramount to the success of treatment. An online survey was conducted in October 2016 showing that out of 166 respondents (various health-care professionals), 133 from 30 different countries showed interest in joining International SDM (ISDM). This shows that critical amounts of health-care professionals are eager to start ISDM.[6,13] There is information available on how to provide information and engage patients in making decisions. The optimal approach depends on the extent of participation (active, collaborative, or passive) the patient wants or needs.

SDM is gaining acceptance in the Western world, leading to improved communication and treatment results.

Shared decision-making scenario in India

SDM in India is recognized as a key factor influencing the doctor–patient relationships, even though it is not part of the health-care policies.[14] Limited publication by Indian authors on SDM was found as compared to that of the Western world. Such inadequate knowledge and lack of data may lead to patient-reported harms including physical or psychological harm, life disruptions, and unnecessary financial costs. India is majorly a self-pay (out of pocket) market, and currently involvement of the patient and family in SDM is limited. Involvement of patients in the planning for treatment is largely limited to tertiary care centers or academic institutes. Further, the influence of beliefs and culture on practices and decisions is more likely in India.[14]

Only limited studies for the application of SDM in cancer patients in India are available. Malik et al. assessed decision control preferences and quality of life in thirty breast cancer patients who underwent hypofractionated RT at a tertiary cancer care center at Hyderabad, India.[15] The Control Preferences Scale scores indicated that about 50% of the patients preferred the treating physician to lead the decision-making and 40% patients preferred to share the decision-making. An active decision-making was reported in only 10% of patients. Decisional conflicts were reported in majority of the patients. Actual treatment decisions were made by the patient (n = 11) or family (n = 8) alone or collaboratively by the two (n = 11). This study reported younger age and better educational and socioeconomic status to be significantly associated with SDM.

In a questionnaire-based study in a North Indian population, breast cancer patients undergoing breast-conserving surgery (BCS) versus modified radical mastectomy (MRM) revealed that only 50% versus 30% patients (BCS vs. MRM) had a clear understanding of the risks and benefits of both procedures in the two arms. Surgeon alone made the decision, 54% versus 73% of BCS versus MRM procedures, showing that most of the decisions were taken by the surgeon on behalf of the patient.[16]

In many circumstances, patients are only involved in the decision-making when the cost of the therapy is high. Based on the clinical practice observation of authors of this manuscript, they feel that there is very limited communication between patient and health-care professionals, and in certain situations, even the family members do not communicate the safety and efficacy concerns of the treatment with the patient. SDM should be encouraged because not only it benefits the patients, but it also makes the therapy more affordable, especially in the Indian scenario.[17]

Lack of SDM in the Indian scenario raises a poor mental and emotional health status of patients and their immediate family members. Hence, there is a huge unmet need on SDM, which needs to be discussed and implemented in India.

DISCUSSION

Burden of cancer in India and treatment options

More than one million cases of cancer have been reported to be diagnosed every year in India. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer GLOBOCAN project, the burden of cancer in India is likely to double in the next 20 years to more than 1.7 million by 2035. It is important to focus on the social determinants of good outcomes in addition to the defining the best approach to treatment. Education is one such area that needs focus and dedicated efforts, for example, education interventions and cessation assistance can improve the outcomes in smokers with lung cancer.[18]

Financial distress is a crucial factor which patients and their family members face during the long-term cancer treatment. Physicians make attempts to determine and help patients plan the affordability for cancer treatment. This is primarily because one of the key contributors to the economic burden of cancer is the direct cost for chemotherapy. The cost of treatment is a determinant for formulary decisions and cancer policies.[19] The rising costs of novel therapeutic agents' limit patient access to adequate treatment.[20] The growing focus on patient-centered oncology care is increasing the demand on physicians' time and effort to engage patients and their families in treatment decision-making.

Advantages and disadvantages of shared decision-making

The advantages of SDM are manifold. SDM has triggered the need for reforms in policies and treatment trends to customize solutions for individualized patient care.[13] This will make care in oncology more focused and targeted. SDM strengthens the bond between the patient and the treating physician and enhances mutual respect and understanding due to collaborative efforts.[21] Decision-making aids help to optimally use time and efforts, as these are specifically designed for components that are clearly associated with benefits. These tools provide a structured guidance for SDM and help to eliminate any options that are not likely to benefit.[3] Table 1 shows the advantages and disadvantages of SDM in practice.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of shared decision-making in practice

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Trigger of reforms in policies and trends | Extended involvement of family, care providers, and extended health-care teams may lead to differences in opinions |

| Focused and targeted cancer care | Need for extensive trainings and effective communications |

| Bond between patient and treating physician | Intense on time and resources |

| Mutual respect and understanding | Physician skills need to be developed |

| Optimal use of time and efforts with decision tools | Ill health, compromised quality of life, and emotional distress due to cancer may interfere with SDM |

| Cost-effective management in cancer care | Inherent complexity due to the behavioral traits and attitudes of physicians and patients |

| Patient-centered care | Patient preferences versus guidelines may lead to conflicts |

| Quality of life for patients |

SDM: Shared decision-making

SDM, when effectively incorporated into clinical practice for oncology, can help to optimize the use of available resources in cancer management. SDM helps to choose cost-effective options in diagnosis and treatment. These are important in conditions like cancer, which may have a prolonged course. SDM is also reported to improve the quality of care and life in cancer patients.[22] SDM is central to and fosters patient-centered care.[2]

SDM, however, is not devoid of limitations and disadvantages. The extended involvement of family, caregivers, and extended health-care teams may invite differences in opinions.[23,24,25] SDM is an acquired skill and calls for extensive training and effective communication. Time and resources need to be allocated for SDM in treatment planning in oncology practices.[26] Ill health, compromised quality of life, and emotional distress due to cancer may interfere with the decision-making capabilities of the patient. Physicians should make a careful evaluation of the support needed in patients and offer the same in a timely manner. Moreover, not all physicians may be skilled enough to help patients participate in decision-making.

Despite the availability of decision-making tools, there is an inherent complexity in SDM due to the behavioral traits and attitudes of physicians and patients.[27] Oncology practices are driven by guidelines. The compatibility of SDM with clinical practice guidelines is still evolving, and the integration of the two needs sustained efforts by clinicians and researchers.[28]

Medicolegal aspects

From legal communication perspective, informed consent is a technical term being used in order to secure the highest regulatory standards, a person deserves, and there are different models of informed consent and decision-making. Now, patient's involvement in decision-making is not only restricted to informed consent, but has also involved principles of patient autonomy and control and challenging the physician's authority.

It is established that communication failures were found to strongly correlate with the medicolegal malpractice litigations. Studies have highlighted that ignoring or failing to identify patient preferences puts clinicians at a higher risk of litigation.[29] Poor communication with the patient and paucity of information are the most commonly reported sources of patient dissatisfaction in health care. Physicians' inability to clearly communicate with their patients due to various reasons, to disclose the potential risks and benefits of the treatment, and to answer their questions to the satisfaction, are common predictors of medical malpractice claims.[30] Documentation of the use of decision support interventions in patients' notes could offer some level of medicolegal protection.

In India, while policies are evolving to reflect a progressive shift in medical practice toward patient-centered care, the approach of SDM has yet to be incorporated as standard care. The task of training physicians with skills and techniques required to facilitate SDM and encouraging patients to express their view is not easy, but the rewards for both can be considerable if implemented.

Application of shared decision-making in India and bridging the gaps

There is a large unmet need for SDM in the current clinical scenarios in India, and gap from the Western world is high. As compared to the Western world, in India, decision support systems are poor, majority of patients are poor, health-care support is underresourced and underdeveloped, and there are lack of polices and guidelines. Majority of the Indian population are rural in nature and majority of the focus is on just health care rather than involvement to sacred decision-making.[14] In addition, patients come from different cultural backgrounds; hence, each patient should be assessed individually before involving them in SDM. While patients feel comfortable and empowered about knowing the disease and treatment details, they are not willing to take the responsibility for the treatment of choice, due to unavailability of structured support in India, when it comes to SDM. Table 2 summarizes the gaps from the Western world and its possible implementation.

Table 2.

The gaps from the Western world and its possible implementation

| Gaps identified | Possible approach to bridge the gap |

|---|---|

| Lack of communication | More frequent and transparent communication between patient and health-care professionals required; this includes the involvement of immediate family members, Discussion on the pros and cons of each therapy, invite for more and more questions (Ask-inform-Ask policy), consensus on treatment and clinical re-evaluation of the combined decision |

| Poor decision support system | Development of decision tools to improve the communication with patients for their preferences, for example, accredited e-learnings for health-care professionals and patients |

| Health-care support is underresourced | Reform of health professionals’ curriculum, patient federation, professional bodies and insurance companies collaborating to define valid indicators |

| Lack of policies or guidelines | Formation of guideline, implementation, and its periodic assessment for improvement. Inclusion of patient representatives and industrial designers toward creating “Patient Decision Aids” |

| Lack of implementation in cancer care | Specialized training to health-care professionals on SDM in life-threatening diseases such as cancer. Train the trainer, designing of personalized aids having risk estimates, include family members |

SDM: Shared decision-making

Though the SDM in India is emerging, moving ahead requires a structured 5-point SHARE approach to achieve the unmet needs:

Include your patient in decision-making

Discuss the various treatment options for efficacy and safety, and its comparison with others

Assessment of patient's preferred treatment

Reach a consensus on the treatment

Evaluation of the mutual decision taken.

Health-care providers have to involve themselves to integrate with patients more actively as partners, in decision-making for cancer care. The integration of artificial intelligence will aid in treatment planning, dose optimization quality, safety, and efficiency of care.[31] A collective effort of policymakers, caregivers, and patients is required to bridge the gaps from the Western world. Chances are high that millions of Indians are already eager to have the conversation.

SDM is an important tool of decision-making during cancer treatment. In India, efforts are required from all stakeholders involved in the treatment decision, to enforce a clearer communication to patients and their family members.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a large unmet need for SDM in the current clinical scenarios in India, and gap from the Western world is high. SDM has evolved during the advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. With an array of instruments and a plethora of treatment options and modalities, it is important to inform the patient and invite the patient and/or family for the preferred choice of one over the other. Further research on patient-centered cancer treatment outcomes and the value of cancer treatment plans is required to fill the gaps between the two. We also propose that a questionnaire-based future research on oncologist's attitude would add value further in this area.

Financial support and sponsorship

Funding for medical writing support was provided by Merck Specialties Pvt Ltd., an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

All named authors met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

The authors thank Dr. Punit Srivastava of Mediception Science Pvt Ltd. for providing medical writing support in the preparation of this manuscript, funded by Merck Specialties Pvt Ltd., an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean.(or it takes at least two to tango)? Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–92. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duggan PS, Geller G, Cooper LA, Beach MC. The moral nature of patient-centeredness: Is it “just the right thing to do”? Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62:271–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frerichs W, Hahlweg P, Müller E, Adis C, Scholl I. Shared decision-making in oncology-A qualitative analysis of healthcare providers' views on current practice. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Härter M, Moumjid N, Cornuz J, Elwyn G, van der Weijden T. Shared decision making in 2017: International accomplishments in policy, research and implementation. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2017;123-124:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz SJ, Belkora J, Elwyn G. Shared decision making for treatment of cancer: Challenges and opportunities. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:206–8. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeder-Hayes KE, Roberts MC, Henderson GE, Dees EC. Informed consent and decision making among participants in novel-design phase i oncology trials. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e863–73. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.021303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gärtner FR, Portielje JE, Langendam M, Hairwassers D, Agoritsas T, Gijsen B, et al. Role of patient preferences in clinical practice guidelines: A multiple methods study using guidelines from oncology as a case. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e032483. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nejati B, Chien-Chin L, Vida I. Validating patient and physician versions of the shared decision making questionnaire in oncology setting. Health Promot Perspect. 2019;9:105–14. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2019.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oostendorp LJM, Ottevanger PB, Donders ART, van de Wouw AJ, Schoenaker IJH, Smilde TJ, et al. Decision aids for second-line palliative chemotherapy: A randomised phase II multicentre trial. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17:130. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0529-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Härter M, van der Weijden T, Elwyn G. Policy and practice developments in the implementation of shared decision making: An international perspective. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2011;105:229–33. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacob KS. Informed consent and India. Natl Med J India. 2014;27:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malik M, Vaghmare R, Joseph D, Kotwal SA, Valiyaveettil D, Jonnadula J, et al. Assessment of decision making, control preferences, and quality of life in patients of breast cancer treated with hypofractionated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:E535–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agrawal S, Goel AK, Lal P. Participation in decision making regarding type of surgery and treatment-related satisfaction in North Indian women with early breast cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:222–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.98974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prazeres F and Martins E. Shared decision making and cancer screening. Ind J Can. 2019;56:195–6. doi: 10.4103/ijc.IJC_574_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKay AJ, Patel RK, Majeed A. Strategies for tobacco control in India: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuomo RE, Seidman RL, Mackey TK. Country and regional variations in purchase prices for essential cancer medications. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:566. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albaba H, Lim C, Leighl NB. Economic considerations in the use of novel targeted therapies for lung cancer: Review of current literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35:1195–209. doi: 10.1007/s40273-017-0563-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulter A. Paternalism or partnership.Patients have grown up-and there's no going back? BMJ. 1999;319:719–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger AM, Buzalko RJ, Kupzyk KA, Gardner BJ, Djalilova DM, Otte JL. Preferences and actual chemotherapy decision-making in the greater plains collaborative breast cancer study. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:1–8. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1374555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisognano M, Goodman E. Engaging patients and their loved ones in the ultimate conversation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:203–6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayman ML, Morris MA. Patients in context: Recognizing the companion as part of a patient-centered team. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noteboom EA, de Wit NJ, van Asseldonk IJEM, Janssen MCAM, Lam-Wong WY, Linssen RHPJ, et al. Off to a good start after a cancer diagnosis: Implementation of a time out consultation in primary care before cancer treatment decision. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14:9–13. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00814-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Politi M, Studts J, Hayslip J. Shared Decision Making in Oncology Practice: What Do Oncologists Need to Know? The Oncol. 2012;17:91–100. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd A, Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Rix A, Elwyn G. Coherence': Using normalization process theory to evaluate a multi-faceted shared decision making implementation program (MAGIC) Implement Sci. 2013;8:102. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L, Beaulieu MD. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):116–31. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joga Rao SV. Medical negligence liability under the consumer protection act: A review of judicial perspective. Indian J Urol. 2009;25:361–71. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.56205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durand MA, Moulton B, Cockle E, Mann M, Elwyn G. Can shared decision-making reduce medical malpractice litigation. A systematic review? BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:167. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0823-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deig CR, Kanwar A, Thompson RF. Artificial intelligence in radiation oncology. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1095–104. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]