Introduction

Evidence suggests that approximately 15.1% of the roughly 73 million people with diabetes in India are affected by depression (International Diabetes Federation, 2017; Mohan et al., 2007). Faced with barriers to accessing mental health treatment (e.g., the stigmatization of mental illnesses, low availability and large distances to psychiatric care facilities, the limited number of trained mental health professionals) patients with depressive symptoms living in India lack sufficient options for accessing treatment and counseling on self-management strategies (Hofmann-Broussard et al., 2017; Khandelwal et al., 2004; Patel et al., 2016).

‘Self-management’ refers to an individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, health consequences, and lifestyle changes associated with chronic disease (Barlow et al., 2002). Self-management involves skill development, an understanding of available resources, and effective communication with healthcare providers and support persons (Wagner et al., 2001; Wagner et al., 1996). The patient activation theory, which draws from the transtheoretical model (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997) and the concept of self-efficacy (i.e., an individual’s belief in his/her capacity to perform a behavior) (Bandura, 1977), was developed to describe the gradual process through which patients take ownership of their health care management (Hibbard & Mahoney, 2010). According to this theory, patients are considered ‘activated’ once they have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to take an active role in their health care and self-management (Hibbard & Greene, 2003). Patient activation also contributes to patients’ willingness to manage their conditions autonomously (Greene et al., 2015; Hibbard, 2003).

Behavioral activation and motivation, an attribute not captured by the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) (Hibbard et al., 2004), are both critical for adherence to chronic care self-management plans (Naik et al., 2008; Parchman et al., 2010). Lack of motivation can act as a patient-level barrier to treatment; however, with the proper support to identify and target motivational factors, build self-efficacy, and develop appropriate chronic disease management goals, individuals can work towards achieving their health goals (Bodenheimer & Handley, 2009; Lorig, 2006; Miller & Bauman, 2014). Building patients’ self-efficacy through education, monitoring, and feedback is essential in enhancing goal commitment for a patient (Bandura, 1997). Health worker-led participant-activation, therefore, plays an important role in treating patients with chronic diseases because clinical diagnosis and patient awareness of his/her condition(s) are the first steps in initiating self-care for depression and diabetes (Wagner et al., 1996).

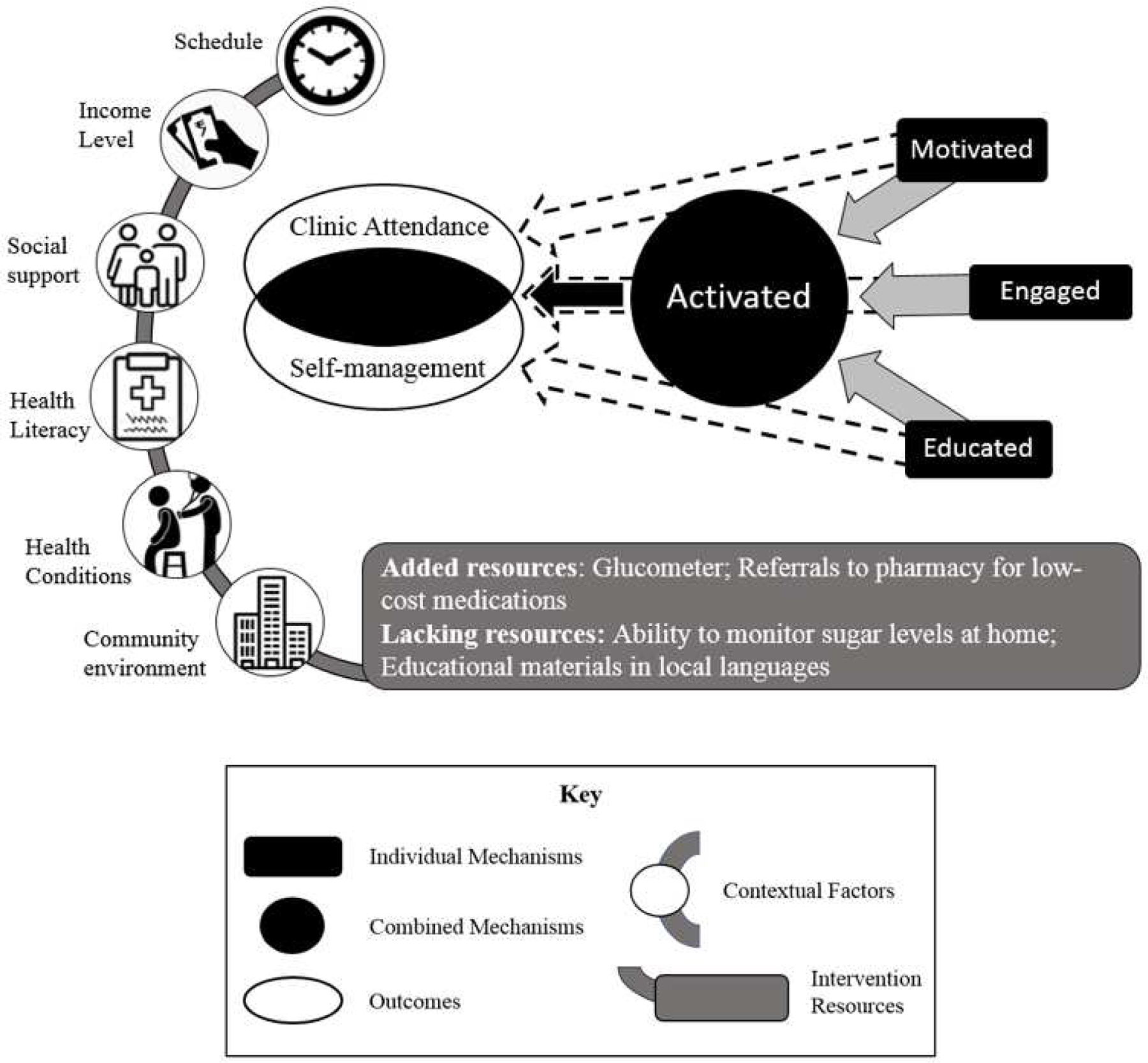

The INtegrating DEPrEssioN and Diabetes treatmENT (INDEPENDENT) care model was developed to address gaps in mental health care and improve diabetes care and management in India (Kowalski et al., 2017; Ali et al., 2020). While this approach largely focuses on quality improvements at the clinic-level, patient engagement and empowerment were considered key to cultivating patients’ diabetes and depression self-management behaviors. Patient engagement and empowerment are two components of patient-centered care that seek to maximize patients’ ability to take charge of their own health care (i.e., be ‘activated’) (Butcher & Selby, 2018). ‘Engagement’ broadly refers to the extent to which patients, and their support persons, are involved in healthcare decision-making processes (Gallivan et al., 2012). Patient empowerment refers to the provision of resources to help individuals define their healthcare needs and the process of supporting them in applying solutions that are patient-informed (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008). Patient engagement, empowerment, and activation have been used interchangeable and inconsistently, making it difficult to clarify the relationship been these constructs. Figure 1 depicts the theoretical relationship between patient engagement, empowerment, and activation that was used to inform this evaluation.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework of Core Theoretical Concepts Contributing to Patient Activation and Self-management.

This diagram draws from the concept of patient activation, as defined by Hibbard and colleagues (2004), and the Patient Health Engagement Model (Graffigna, Barello, & Bonanomi, 2017) to describe how activation for self-management among patients is achieved through processes of patient empowerment and engagement.

Improving patient self-efficacy to self-manage chronic conditions requires continuity in care while he/she receives counseling and treatment. In India, where over 70% of health care costs are paid for out-of-pocket, health care consumers have flexibility in selecting where they seek medical treatment, and therefore, change their providers if they are not satisfied with the care they receive (Balarajan, et al., 2011). Therefore, it is important to examine what motivates patients to initiate care and what factors keep them engaged and activated.

This study was designed to explore patients’ experiences with the INDEPENDENT care model, and how, through engaging with the model over time, patients altered their approach to chronic disease self-management.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A realist process evaluation was conducted alongside the INDEPENDENT randomized, controlled trial (Kowalski et al., 2017) to gain a deeper understanding of contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes (with linked contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes referred to as CMOCs) associated with the integrated care model (Pawson & Tilley, 1997). Realist evaluations occur over three phases of theory development, testing, and refinement, where initial assumptions about how an intervention will work are tested and refined through primary data collection focused on program outcomes and the grouped contextual factors and mechanisms that generate them (Pawson & Tilley, 1997). The initial program theory for this evaluation, developed from key informant interviews and a document review, outlines the hypothesized causal mechanisms underlying how the INDEPENDENT care model works. Table 1 presents the theoretical patient-related CMOC. This paper seeks to identify what mechanisms and corresponding supportive conditions motivated and empowered patients to manage their own health.

Table 1.

Hypothesized Context-Mechanism-Outcome Configuration (CMOC)

| CMOC | Inputs (I) and Mechanisms (M) | Outcomes | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | If the patients are provided with 6-monthly travel reimbursements and intensive quality care at no additional cost (I), then patients will be empowered (M) | To attend clinic visits and self-manage one’s conditions | When patients face barriers to health services and medication, lack social support, have limited health literacy, and depression is a stigmatized condition |

The INDEPENDENT Care Model

The INDEPENDENT care model is a multi-component depression and diabetes care program implemented in diabetes clinics in four cities in India. This care model combines the strengths of both the TEAMcare (Katon et al., 2010) collaborative care approach and the CARRS trial multi-component quality improvement strategy (Ali et al., 2016). In the INDEPENDENT care model, care coordinators (CCs), trained health care workers without a prior background in mental health, were hired and trained as additional human resources to deliver behavioral interventions to support patients’ sustained depression and diabetes self-management. Through therapeutic approaches, such as motivational interviewing, providing patient-education, employing self-efficacy enhancement strategies, and monitoring depressive symptoms and cardiovascular disease (CVD) indicators, the CCs provided on-going, individualized patient care to intervention patients. Further enhancing the responsiveness of this care model, the CCs utilized decision-support software equipped with evidence-based algorithms that prompted guideline-based treatment options based on updated lab results and patient health information.

Participants.

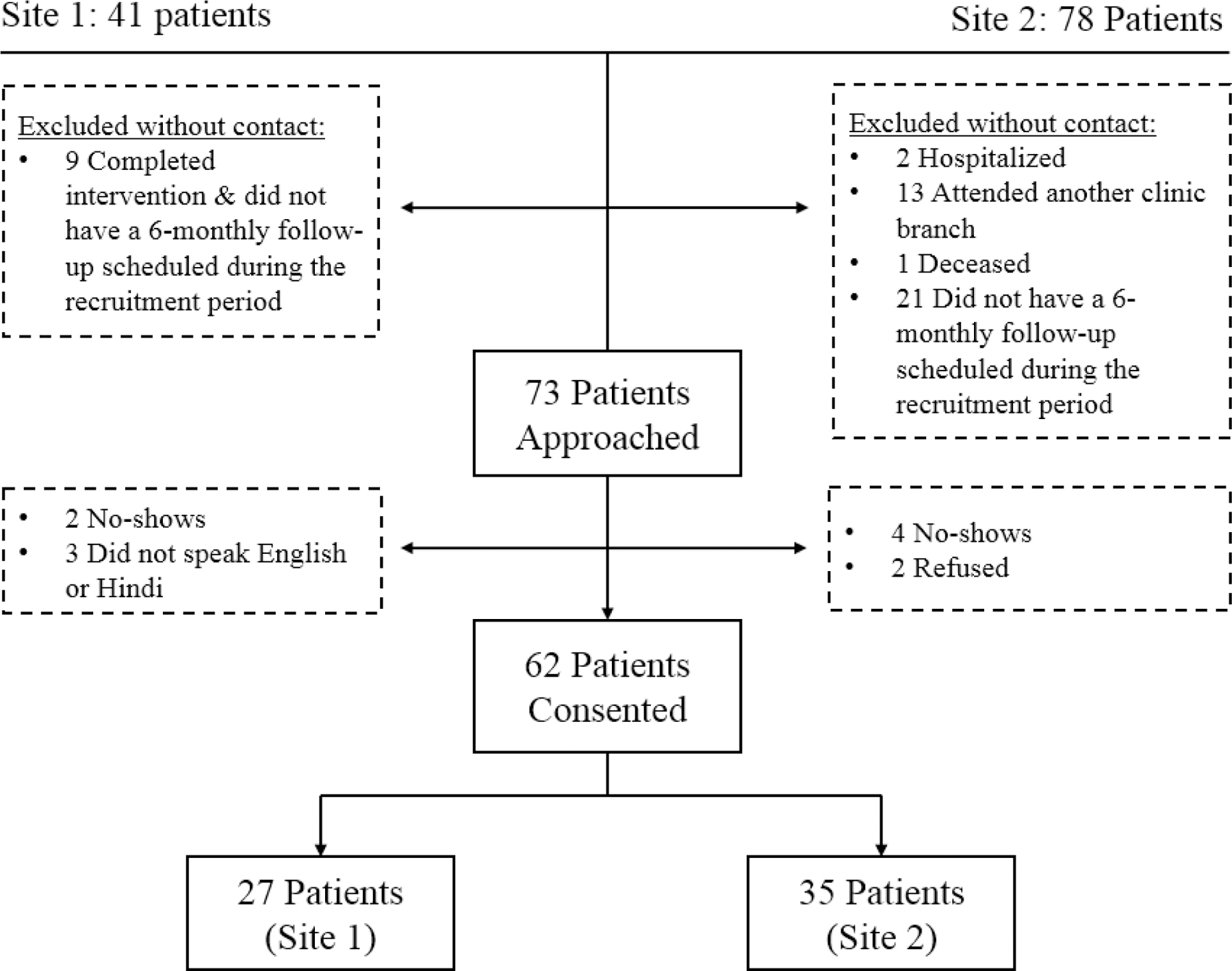

The INDEPENDENT trial took place between March 2015 and July 2018, with participants recruited at outpatient clinics in four cities (i.e., Chennai, Bengaluru, Visakhapatnam, New Delhi) in India. Eligible participants were adults (aged ≥ 35 years) with one or more poorly-controlled CVD risk factor(s) in the previous six months and newly-identified depressive symptoms. Only patients receiving the 12-month active intervention at two of the largest and contrasting of trial sites were included in this evaluation: one government clinic in north India and one private clinic in south India. These sites enrolled 41 and 78 patients into the intervention arm of the trial, respectively. All intervention patients were eligible to participate so as to allow for comparison of data based on differing socio-cultural factors and support features introduced by the clinics. Data collection and analysis took place in parallel, with recruitment stopping when data saturation (i.e., the point at which no new data related to the CMOCs emerged) was met. A total of 62 patients participated in in-depth interviews (see Figure 2). The mean age of participants in this evaluation was 53 years and 34 (55%) patients were female. A complete sociodemographic profile of all INDEPENDENT trial participants is available in the INDEPENDENT trial’s study design paper (Kowalski et al., 2017).

Figure 2.

INDEPENDENT Evaluation Study Recruitment

Interview Procedures

An interview guide was developed to elicit patient experiences with the INDEPENDENT care model and approaches to healthcare communication, with probes designed to encourage elaboration on how intervention components and healthcare interactions supported patient self-management and healthcare utilization. LJ piloted and refined the interview guide based on patient feedback and clinic observations prior to data collection. Changes to the guide included having patients define depression and adding probes regarding patient privacy. Interviewers obtained informed consent by a written signature from all participants prior to each interview. Interviews were conducted in private rooms at each clinic.

Two trained interviewers from the local communities (non-clinic staff members), one at each site, and LJ conducted patient interviews across both sites while the trial was ongoing. The local interviewers were bilingual in English and the predominant local language (i.e., Hindi, Tamil) of their respective cities. Interviews lasted from 40–60 minutes and were audio-recorded. Interviews at the government clinic, site one, were conducted from September to December 2016 and interviews at the private clinic, site two, were conducted from February to May 2017.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Emory University, USA, and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences and Madras Diabetes Research Foundation, India.

Qualitative Data Preparation and Analysis

The bilingual interviewers translated and transcribed all patient interviews. A third-party read a sample of transcripts with the corresponding audio and noted any discrepancies. No major discrepancies were identified in this process. We followed the realist analytic approach detailed by Punton and colleagues (2016). Once a transcript was complete, it was de-identified and coded independently by two evaluation team members into an EXCEL spreadsheet according to contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes. Codes were then clustered into CMOCs, which were later compared to the hypothesized patient-related CMOC to produce a refined program theory regarding patient participation and self-management (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Revised Program Theory

Results

Patients receiving the intervention in the INDEPENDENT trial described how the added support they received in this care model influenced their willingness to continue participating, as well as their ability to self-manage their diabetes and depressive symptoms. This study aimed to empower patients, but patients revealed that while they felt confident in their ability to apply their skills and knowledge, their inability to control numerous factors impacting their self-management behaviors (e.g., ability to purchase healthier food options, competing work and family demands) left them incapable of effectively self-managing their diabetes and depressive symptoms . Instead, patients detailed a gradual progression through feeling motivated, engaged, and educated about how to manage their conditions before feeling confident in their abilities to manage both conditions (see figure 4). In a few cases, patients reported being engaged but blindly followed guidance from the health care providers regarding attendance and self-management behaviors. In those cases, patients did not feel confident proactively seeking health care or sustaining self-management behaviors without the support of the CCs.

Figure 4. Patient Participation and Self-management Related Contexts, Mechanisms, and Outcomes.

The figure depicts how each of the three identified mechanisms (i.e., motivation, engagement, and education) individually contributes to one or both of the outcomes (i.e., clinic attendance and self-management) as indicated with dashed arrows, but the presence of all three mechanisms as indicated with solid arrows resulted in patient activation which enabled patients to manage their conditions without the structure provided by the study. These mechanisms were triggered differentially based on key contextual factors. Clinic-level resources were added to address barriers to care.

Across the interviews, patients emphasized how the CCs enhanced their ability to self-care by educating them about diet, exercise, and medication adherence, and through encouraging them to develop coping strategies for stress. Over time, patients’ relationships with the CCs, and the noticeable improvements in their health and well-being, further motivated engagement with this model of care. Patients differed by what motivated them to attend clinic appointments, what strategies were used to engage them in collaborative care, and the amount of time and resources it took for each of them to feel knowledgeable and capable of chronic disease self-management. Factors that patients consistently identified as barriers to self-management included not having a way to monitor their blood sugar levels at home and not being able to fully engage with the provided educational materials, due to low literacy. The contextual factors that determined if and how mechanisms were activated included a patient’s community environment, co-existing health conditions, health literacy, social support, income level, and schedule.

Motivation

Travel reimbursements were hypothesized to motivate patients to attend study visits, with low-cost, quality, intensive care serving as a motivator for continued attendance at clinical visits (i.e., intervention involved clinical care). The majority of patients, however, reported the “VIP (Very Important Person)” treatment they received at clinical visits was their main reason for continuing with this form of care. The VIP treatment was broadly defined as having all counseling and medical care, and the accompanying logistics, handled with care and concern (see Table 2 for an expanded list and examples of defining characteristics). Though many patients felt travel reimbursements should be provided for all clinic visits, in order to make this form of care accessible to patients of all socio-economic backgrounds, no one named this as a motivating factor for study participation. Nearly all patients mentioned that they had agreed to take part in the study in order to improve their health and quality of life.

Table 2.

Characteristics of VIP Treatment

| Characteristic | Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|

| Cost-effective | “I will be treated freely here. If I get treated [at another clinic] I have to pay. As I am not wealthy enough I did not go [to another clinic].”-site 2 |

| All-inclusive | “For everything… kidney problem, lungs, eye pain, body pain, headaches, leg pain. Not just treating for one but for all.” -site 2 |

| Reduced wait time | “She takes me directly to the doctor and I don’t have to be in the queue. I come here according to the appointment and with her help, I meet the doctor in lesser time than others.” -site 1 |

| Fixed appointments | “They call me at a regular time span for checkup. I don’t have to worry about making calls to them and asking about my appointments. They are worried about my health more than myself.” -site 1 |

| Comprehensive health education | “The best thing is they ask each and everything about my health. If they feel anything important they explain. If I mention anything which I have noticed problematic then they explain. They explain it to me till the time they are convinced that I have got whatever they said.” -site 1 |

| Patient advocacy | “Since we cannot speak English, we cannot fully convey our feelings to the doctor, but coordinators help us in that.” -site 1 |

| Well-mannered approach | “They talk very nicely. You know, there are so many places people don’t even talk softly. They will be talking to you in a very rude way, almost like scolding. Here it is not like that. I have never felt or faced anything of that kind. Sometimes they scold me, but for the sake of my best interest only. That happens only when I am not following their instruction.” -site 1 |

| Provider accessibility | “I got severe pain at 3 am in the morning so I immediately called [the care coordinator]. I didn’t know where to go… at that time I got reminded of her and called her.” -site 2 |

| Outcomes oriented | “If our blood sugar is high they would ask us to work towards reducing it in a good manner. Even if it is my mistake, they would encourage me to stay controlled. We don’t experience these things [other clinics]. This is also a major reason for being in study.” -site 2 |

| Family-treatment | “When they call us to visit [the clinic] I get a feeling of ‘home’. They are behaving so humbly and lovingly. They don’t treat patients as patients. They treat us like their family member.” -site 2 |

For many patients, what distinguished this care approach from other health care experiences was feeling that their health care providers were deeply invested in their well-being, rather than viewing patient care as a business transaction. This sentiment is best captured by one patient who stated, “No one [in other clinical settings] used to care whether I take the medicine or not, whether my sugar level is going up or down, how I am living, or anything.” Patients trusted their health care providers and CCs to act in their best interest because they had witnessed the staff’s personal investment in and dedication to helping patients control their diabetes and/or reduce their depressive symptoms.

At the core of the trust established between patients and providers was that patients felt as if they were receiving treatment akin to what providers’ family members receive, one of the defining characteristics of VIP treatment. Expressing a cross-cutting theme, one patient summarized this notion when she stated, “[The CC] will look after me, treating me like her own mother or grandmother.” Over time, patients reciprocated this bond, as demonstrated when they frequently referred to the CCs as family members and referenced them with affection and appreciation. One patient commented, “I consider them as my sisters and share personal talks. I consider them doctor, sister, and friend,” highlighting how this pseudo-familial relationship between a patient and a CC helped establish rapport and improve the exchange of sensitive information.

Patients valued having medical providers who are empathetic and patient-centered, naming these as primary reasons for continued clinic attendance in the face of conflicting family responsibilities or work schedules. The main impediment to attending clinic appointments was poor health resulting from another health condition(s) (e.g., Tuberculosis), though as patients became engaged in their care, they were able to rebound from these setbacks with the help of their health care providers.

Education

Though many patients shared that they had family members or spouses who had diabetes, most reported learning about the disease through participation in this study. Patients valued the counseling provided by the CCs, as is best captured in one patient’s comment, “The best thing here is the facility of counseling. Since doctors don’t have time to tell us about the precautions and other necessary information needed for better treatment, the [CCs] fills that gap. And that, I think, that is the most important thing.” Patients, however, varied in understanding how they came to develop diabetes. A subset of participants across both sites was upset and confused by being the only person in their family with the disease. As expressed by one patient, “In my family, no one is having sugar. I don’t know why it happened to me. It might be written in karma.” There were also mixed understandings about the duration of diabetes, with some patients expressing frustrations over not knowing how long they would have to maintain the advised diet and medications.

Patients also had varying beliefs about depression, describing it as a natural and manageable phase of life, a temporary state of mind, a side effect of diabetes, or a psychological disease, which some thought may be permanent. Only a few patients had knowledge of available treatment options. Those patients who required anti-depressants described being counseled about depression at the time of their diagnosis, and how it helped them better understand the symptoms they were experiencing. One patient elaborated:

I was totally ignorant about it. I used to think my mind has been disturbed, because of which I am not being able to sleep. I have learned that when someone has depression that does unexpected things. But I never thought that it would happen to me as well, as I think that I should have died. Or, sometimes, people start behaving like mad, so many other nonsensical things. Even I used to do all that. Now, I got to know that it is because of depression.

Patients not only learned approaches to improve their mental health, they learned how their diabetes and other health-related behaviors affect their mood and vice versa. One patient explained, “My sugar level is under control, but any carelessness with the food makes it unbalanced. When I take my medicines regularly and it gets controlled, but sometimes because of ‘tension’ it gets increased.” Patients recognized that their conditions influenced one another, which further motivated them to control each individually.

Patients learned more about their conditions with each additional counseling session. Though many patients felt they initially prioritized medication adherence, they found themselves equally or more concerned with diet and exercise (e.g., walking) by the end of their time in the active intervention. During the early counseling sessions, every patient received supplementary educational materials on diet and nutrition, though many were only able to use them if they had a family member who could read the materials to them. The CCs coupled these materials with extensive dietary guidance. Though the majority of patients reported that altering their diet was the most challenging part of their self-management due to issues of self-discipline, changing household norms, and accessing healthier food items, nearly all patients echoed the following statement of one patient: “[the CC] makes me understand that I should control my diet.” Several patients expressed a desire to have counseling on exercise and weight loss, which they felt was lacking. Physicians and CCs advised walking as exercise, which many of the patients did not identify as a form of exercise. The counseling sessions were also used to enhance patient adherence to medications, which demanded problem-solving for the barriers to attaining medications, in addition to educating patients on the importance of medication adherence.

Engagement

Reflecting on their expectations at the start of the study, patients expressed a desire for a passive healthcare experience, but over time, the majority of patients became comfortable playing a more active role in managing their health. Numerous patients recounted situations where they were willing to call on the CC(s) to guide them regarding their diet or provide solutions during a medical emergency. One patient shared, “When I have a crisis situation, then I make call to the care coordinators and if they don’t have solution for that, then they take me to the doctor. I keep them informed about my health.” Patients’ perceived the act of consulting a physician or CC as being active in one’s health care, especially when these communications were coupled with agreed upon lifestyle change strategies (e.g., improving diet and increasing physical activity) at home. This stands in contrast to how patients described their approach to diabetes management prior to engaging in the INDEPENDENT care model. Patients described that they previously felt that patients did not have a role in their medical treatment and that they considered medication adherence to be the only necessary responsibility of the patient outside of the clinical setting.

Patients’ resistance to taking a more active role in their health care was largely influenced by their available income and social support. The majority of patients had other chronic and infectious health conditions aside from diabetes and depression that demanded their attention. This left many patients in the position of having to pay for additional clinic fees and medications on a limited income, without even accounting for other family members’ healthcare costs. The low-cost care offered at the sites in this trial allowed patients to more readily partner with the CCs to identify health goals and problem solve other potential barriers to reaching those goals.

As CCs developed rapport with patients, they encouraged patients to brainstorm solutions to their own health challenges, which, beyond income, were often linked to a patient’s schedule. Both men and women felt that work and family responsibilities hindered their ability to fully focus on their own health care needs. One man shared his daily schedule when elaborating on why he does not exercise more, stating, “I go to work at 10 am and return home by 10 pm and then have dinner and go to bed late and again wake up early to work—this is how my time is spent.” Whereas men voiced concerns about not being able to support their families if they risked their job to take more time to eat healthy, exercise, and seek medical care, women typically reported finding it difficult to prioritize their health over that of other family members. For example, one woman shared how her health was suffering physically, mentally, and emotionally because she always put her husband’s needs before her own:

I can’t take rest after doing my chores… [my husband] does not think that I have to sit and rest for a while… I should finish his work first. As soon as he comes I have to serve him with dinner and then, I have to make his bed and I have to massage him with pain killer balm for his joints. He doesn’t think about me at all, whether I have eaten or not… these things hurt my heart.

Upon sharing her situation with the CC, they identified small ways to improve her mood through exercise at home, such as “climb[ing] stairs up and down to sun dry washed clothes,” in addition to taking her prescribed anti-depressants. Patients found it helpful to recount their daily routines with the CC(s) and identify opportunities to build-in activities for self-care (e.g., yoga, prayer, time with family and friends).

A common strategy employed in this collaborative care approach was to involve patients’ family members in counseling, in order to provide patients with support and positive reinforcements at home. In discussing with patients how they manage their conditions, it was almost inevitable that a patient would name one or more family members as critical to their health care and well-being. One woman succinctly stated, “[My son] takes care of me and buys me medication, sarees, basic necessities. He, only, takes care of me. If he ends up in any problem there is no one for me.” Another man explained:

My wife takes care of it. She is like a counselor, too. She would say that the counselor asked you to eat this, so, eat it… I must eat what she cooks. She will be present during counseling, right! She is the important person. She will make food that fits me. My wife takes care of everything. She is like a doctor to me because she injects insulin and I don’t know about my medication, but she gives it to me.

Patients recognized that they were not only reliant on their health care providers for treatment but that they needed the support of their family to manage their conditions. From taking an individual to her/his physician appointments to buying her/his medication, the family played an important role in supporting patient self-management across both sites.

Activation

Across both sites, the majority of patients felt confident that they could use the knowledge and skills that they learned in counseling sessions with the CCs to take responsibility for their diabetes and depression self-management. When asked how the CCs could better assist patients in achieving their health goals, every patient replied that it was the responsibility of the patient to apply her/his new-found knowledge and skills in order to improve her/his health. One patient captured those views, stating, “[The CCs] can’t do more. Their job is to give patient right information and they are fulfilling their job nicely. If we are the one who is not working then in that, [the CCs] are not having any fault.” In reflecting on how their health behaviors had changed since joining the study, patients contrasted prior instances of uncontrolled diets and non-existent exercise regimens to more consistent daily regimens including stricter diets, exercise routines, improved medication adherence, and attention to one’s mood. One patient characterized the onus of patient self-management with the comment, “They guide me about my diet and I put control on myself,” indicating that the health care providers may provide resources, but it is the patient who has to control her/his lifestyle in order to reap the health benefits. Another patient echoed the importance of self-control with the statement, “I hold control over myself and control over emotions so that it doesn’t affect my health.” Despite feeling responsible for their health, patients still relied on the CCs, however, to facilitate their care and on the physicians to determine their medication needs in light of patients’ circumstances.

With additional health education, patients noted a greater awareness of the role of different behaviors in influencing their physiological health, as a result of changes in their health status over time. Those patients who showed improvements in their diabetes and depressive symptoms often recounted that they first recognized this connection when they disregarded the lifestyle changes advised by their CC or physician. For example, one patient shared, “When my sugar level increased, that was all because of me only. I was careless. As I keep going out for outside dinner and other parties, then the next day it will be increased,” when noting the importance of maintaining a healthy diet in social settings where a range of food options may be presented and where others may not have to abide by the same dietary restrictions. Patients also expressed improvements in their self-confidence to self-manage their chronic conditions as a result of remaining engaged with the care model. The majority of patients expressed feeling confident in their ability to sustain their diabetes self-management. As one patient commented, “Earlier, I won’t check my blood nor take medication properly, but here, I have come and gained confidence and am taking proper medication.” Few patients referred to behavioral strategies for improving their mental health, with only one patient explicitly expressing more confidence in his ability to manage his depression moving forward. This individual put his current self-assurance in perspective by recounting his state of mental health and attitude towards self-care at the start of the study:

Earlier I used to have negative thoughts about myself. My self-confidence was extremely low. I can’t imagine that time. [I thought] about suicide and all. It was like there was nothing in my life after this disease, and living would be worthless.

These shifts in physical symptoms and mood helped patients track and manage their progress.

Though patients had faith in their ability to self-manage their health, a number of contextual factors were identified as keeping patients from feeling fully capable of controlling their health care and self-management. Self-reported factors that limited patients’ self-efficacy include income, additional health conditions, their community environment, and social support. Low income was described by the majority of patients as a factor that determined not only where a person could seek medical treatment, but the extent to which they could engage in the behavioral interventions. One patient shared that she was unable to follow the dietary guidelines provided by the CC due to the high price of fruit, stating, “I cannot afford it, I am not rich to follow those food patterns.” Having multiple medical conditions or illnesses on a limited income often resulted in patients only purchasing the cheapest prescribed medication, in addition to limiting a patient’s ability to exercise. One patient explained how contracting a viral infection inhibited his exercise routine established as a part of his chronic care self-management. In the patient’s words, “It has been 1 month 20 days since I had Chikungunya [viral disease]. You won’t believe it is so painful that I am not being able to stand because of the severe joints pain.” The availability of community spaces to walk, let alone time in one’s schedule to maintain the practice, and menu options at restaurants all further limit patients’ ability to control their depression and diabetes self-management. Unlike diabetes, which patients acknowledged was commonplace, patients felt they could only discuss their emotional and psychological problems with select family members, close friends, or their CC. Patients perceived there to be limited places to seek support when they were feeling depressed.

As patients became more confident and comfortable taking an active role in their health, any noticeable improvements in health and well-being were an added motivation to stay engaged in this model of care. One patient expressed, “I am sick and I am getting good treatment here. My health is improving, so I am coming.” Even though it takes time to see marked improvements in CVD and depression indicators, particularly in terms of glycemic control, patients were encouraged by the gradual improvements in their health. Many patients also expressed having better control over their emotions, noting that they were not as quick to anger. It was common for patients to experience periods of uncontrolled CVD risk factors or depressive symptoms as a result of specific events or periods of travel that disrupted their established routines, but most patients viewed the long-term reduction in symptoms and medications as an improvement in their quality of life. In a sub-group of patients, the perception existed that one only has to control diet and exercise or medication adherence in order to see improvements in health. Whether patients were motivated by improvements in health outcomes or demotivated by unmet expectations and slow progress, these responses served as a feedback loop to hinder or enhance patient engagement and activation.

Discussion

This realist evaluation explored a patient-based mechanism embedded in the INDEPENDENT trial and shows that both patient self-management and utilization of healthcare services provided through the intervention were triggered when patient activation was achieved. Patient self-management practices for chronic disease care have been previously found to vary by patients’ level of health literacy, motivation, and engagement (Coventry et al., 2014; Nielsen-Bohlman et al., 2004; Simmons et al., 2014). Results from this study reiterated these findings and further demonstrated that patient activation occurs when patients are cumulatively motivated, educated about, and engaged in, their treatment. Additionally, the results of this study indicate that there is a distinction between what motivates patients to initiate and continue participating in treatment versus what motivates patients to take an active role in their health care and engage in self-management practices. This is consistent with the difference between initiation and maintenance described in the literature (Rothman, 2000).

The quality of the relationship between patients and their health care team was a critical underlying feature of what motivated patients to further engage with their care. The care and concern displayed by the providers distinguished this care model from patients’ healthcare experiences in other settings, and reinforced the other dimensions of “VIP” treatment that patients described receiving (e.g., perceptions of getting the ‘family-treatment). This suggests that human factors in healthcare, such as the consistency and the qualities of patient-provider interactions, are key in improving patient health outcomes. The CCs were important in establishing patient relationships, therefore, efforts to maintain and scale this care model requires institutional investment in staffing these positions and consideration of how many CCs would be needed to support the patient population. Though frequency and duration of counseling sessions with CCs decreased as patients gained confidence in their ability to self-manage their conditions, patient loads should not exceed the CCs ability to provide quality, patient-centered care.

The INDEPENDENT care model intervened at the patient and provider-level to improve health outcomes for people with diabetes and depression (Kowalski et al., 2017). With a focus on individualized care, the intervention was successful in addressing individual-level problems raised by patients (e.g., identifying ways to fit physical activity into a patient’s daily schedule) to promote patient activation. However, the revised program theory indicates that patients fell short of feeling empowered because they still face barriers to healthcare utilization and self-management at the household-, community-, and society-level. Because care components targeted problems at the individual-level, the intervention did not address higher level contextual factors found to influence underlying program mechanisms, such as social support, community environment, and gender norms. Broader social interventions are needed to promote family engagement, health-centered urban design, and women’s rights within this setting. Additionally, since patient activation shares common domains with empowerment (Hibbard et al., 2004; Wallerstein, 2006), further research is needed to examine the relationship between these constructs and the extent to which the lack of assets and capability to address multi-level barriers to active self-management may inhibit higher levels of patient activation.

The gradual acquisition of relevant health education and engagement with health care providers through behavioral interventions, namely goal-setting and action planning, outlined in the revised patient-related program theory align with those patient responses anticipated across the first three levels of activation defined by the PAM (Hibbard et al., 2004). According to the PAM, self-efficacy is a component of patient activation that is inherent in the higher levels of activation, wherein patients take action and maintain behaviors (Hibbard et al., 2004). These findings also align with the Transtheoretical Model (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997), which shows that self-efficacy increases across the stages of change that individuals move through to enact intentional behavior change. Patients in this study reported feeling confident in their ability to maintain their motivation, with mixed feelings about the extent to which they could control their behavior, given the presence of social and environmental constraints.

Among patients with diabetes there is evidence that high levels of patient activation are positively associated with high levels of self-care (e.g., regular exercise, glucose tracking) and lower levels of fatalism about one’s health (Hibbard et al., 2004; Zimbudzi et al., 2017). These findings align with outcomes of this intervention, where efforts to trigger patient activation in an integrated care model targeting high-risk patients with diabetes also promoted depression self-management, even when behavioral strategies were not framed as depression-focused. As seen in the revised program theory for this evaluation, intervention feedback loops operate to benefit self-management practices for both conditions. More so, patients appreciated the holistic care approach (a characteristics of “VIP” treatment) and engaged with the care model to navigate care for other chronic and infectious health conditions.

Family engagement and motivation are critical elements supporting patient activation in the Chronic Illness Care Model (Von Korff et al., 1997), which is consistent with findings from this study. Patient activation strategies used by the CCs in the INDEPENDENT care model to engage patients in their health primarily focused on educating patients and their family members about the patients’ health and involving both parties, when patients consented, in making care decisions. Since the chronic care model requires patients be informed and engaged in their care (Wagner, 1998), future work should examine how to best support patient activation in a cultural context of shared family decision making. Counter to previous findings (Bilello et al., 2018), care and concern in treatment was essential to the “VIP” treatment patients viewed as motivational to being active in their health care and self-management. Patients prioritized the quality of their relationship with the CC over the physician with whom they spent little time within the entirety of the treatment process. As such, the CCs in this care model were able to maintain up-to-date information on patient health and life circumstances from which the physicians and specialists could draw to treat patients.

The contextual features highlighted in this realist evaluation expand the evidence base on what social processes impact chronic disease self-management in India. A limited number of studies from India have provided evidence supporting that psychosocial and cultural factors are important to diabetes self-management; only one of these studies focused on patients with diabetes and depression (Sarkar & Mukhopadhyay, 2008; Shobhana et al., 2003; Sridhar & Madhu, 2002; Sridhar et al., 2007; Weaver & Hadley, 2011). Findings from this study indicate that normative social roles and lack of social support hinder self-management practices, but that individualized counseling support can provide pathways to promoting health behavior change in this context. While this evaluation did not assess what shared-decision making looks like in the Indian context, patients’ expressed willingness to take a more active role in their health care as a result of participation in the intervention suggests that patient-centered care can be effective in diverse settings. This stands in contrast to recent evidence from low- and middle-income countries challenging the acceptability and effectiveness of patient-centered care in settings where socio-cultural contexts differ from those found in the West (Hall et al., 2019; Sohal et al., 2015).

Strengths.

This study is strengthened by its in-depth examination of patient health care and self-management experiences as there is a notable lack of patient perspectives in existent evaluations of integrated care models. The interviewers were not involved with intervention delivery and were introduced to patients as independent evaluators to encourage unbiased responses. The interviewer took time prior to each interview to stress that all responses would remain confidential and that patient care would not be affected in any way by the feedback provided, though it is possible that response bias occurred due to the fact that patient interviews were conducted while some patients were still in the active portion of the intervention.

Limitations.

This evaluation was unable to separate diabetes and depression self-management outcomes because there is alignment between the lifestyle modifications used to support improved mental health and cardiometabolic outcomes, and CCs targeted both health outcomes with the same behavioral interventions, leveraged in different ways. Due to a limitation in time and resources, only the two largest and contrasting of the four trial sites were included in the evaluation. Additionally, because this study is limited to patients enrolled in the INDEPENDENT trial, it is possible that patients excluded from the trial may have different experiences if engaged in this model of care. Future work should explore how co-morbid conditions that impact cognitive and physical functioning (e.g., dementia, stroke, eye and kidney & foot disease) alter patients’ strategies and present new barriers to or opportunities for accessing care.

Conclusion

Identifying the underlying mechanisms and contexts that trigger the patient activation process can help providers leverage resources that support patient education and engagement in the INDEPENDENT care model (e.g., educational materials, access to reduced or free medications) and enhance features of care that motivate patients (e.g., positive and sustained patient-provider relationships) to sustain behavioral change. The revised program theory presented can help in the allocation of clinic resources and in informing provider training for future efforts to implement integrated depression and diabetes care. While these findings reflect the operational context of urban diabetes clinics in India, the abstracted mechanisms within a realist program theory aim to be transferable to other settings with shared features (i.e., low-resource diabetes clinics seeking to integrate depression treatment) (Pawson & Tilley, 1997). The revised program theory presented provides a basis from which future studies on integrated depression and diabetes care, occurring in different contexts, can test and refine CMOCs linked to patient engagement and activation.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights:

Motivation is necessary to both stimulate and sustain patient activation

Sources of patient motivation change as patients engage in treatment and counseling

Positive patient-provider relationships and integrated care incentivize engagement

Patient empowerment was difficult in the face of socio-economic barriers

Acknowledgements:

INDEPENDENT Study Group:

-

1

Executive Committee: Mohammed K. Ali, MD, MSc, MBA; Lydia Chwastiak, MD, MPH; Viswanathan Mohan, MD, PhD, DSc, FRCP; Subramani Poongothai, PhD; Mark L. Hutcheson, BA

-

2

Coordinating Center: Subramani Poongothai, PhD; Nandakumar Parthasarathy, BPharm; Mark L. Hutcheson, BA

-

3

Data Management and Analysis team: Karl M. F. Emmert-Fees, MPH; Shivani A. Patel, MPH, PhD; Jeba Rani, MBA

-

4

Development of Decision-support Electronic Health Record software: Cygnis Media (https://www.cygnismedia.com/), Mark L. Hutcheson, BA; Alysse J. Kowalski, MPH, PhD; Mohammed K. Ali, MD, MSc, MBA

-

5

DSMB members: K M Prasanna Kumar MBBS, MD, DM (M S Ramaiah Medical College, Bengaluru, India); Pallab Maulik, MD, PhD, MSc (George Institute for Global Health, Delhi, India); N. Sreekumaran Nair, PhD (Manipal University, Manipal, India); Usha Rani Pingali, MBBS, MD (Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad, India)

-

6

Site Investigators and research staff:

Publicly-funded Clinics

-

a

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi:

PI: Nikhil Tandon, MD, DM, PhD

Co-I(s): Rajesh Khadgawat, MD; Rajesh Sagar, MD, PhD

Care Coordinator(s): Chandni Chopra, MSc; Bhanvi Grover, MSc; Deepika Khakha, MSc

Outcome Assessor(s): Radhika Tandon, MBBS, DO; Tania Bhardwaj, MSc; Priyanka Rawat, MSc

Recruiter/Screener: Jijo Joseph, DipNurs

Private Clinics

-

b

Dr. Mohan’s Diabetes Specialties Center, Chennai

PI: Viswanathan Mohan, MD, PhD, DSc, FRCP

Co-I(s): Radha Shankar, MD; Ranjit M. Anjana, MD, PhD, FRCP; Sethuraman Jagdish, MBBS, MMed; Pathasarathy Balasubramanian, MBBS; Selvam Kasthuri, MBBS, DDip

Care Coordinator(s): Bhavani B. Sundari, MSc; Phebegeniya Stephen, MSc

Outcome Assessor(s): Kulasegaran Karkuzhali, BSc; Vijayaraghavan Prathibha, MBBS, DO, FRCS, PhD; Ramachandran Rajalakshmi, MBBS, DO, FRCS, PhD

Recruiter/Screener: Viswanathan Kannikan, MSc

-

c

Diacon Hospital, Diabetes Care and Research Center, Bangalore:

PI: Sosale R. Aravind, DNB, FRCP

Co-I(s): Bhavana Sosale, MD, FRCP; Pooja Rai, DipPsych

Care Coordinator(s): Raghavan Karthik, BCom, DipCLS

Outcome Assessor(s): Rangawamy Geethanjali, BPharm

Site Manager: Sunita K. Somaiah, MD

-

d

Endocrine Diabetes Center, Visakapatnam:

PI: Gumpeny R. Sridhar, MD

Co-I(s): Madhu Kosuri, PhD

Care Coordinator(s): Aruna Sri Sikha, MA

Outcome Assessor(s): Venkateswarlu Chiramana, PhD; Nagamani, MBBS, DO

-

7US Collaborators:

- University of Washington: Jurgen Unutzer, MD, MPH, MA; Wayne Katon, MD (deceased)

- Emory University: Leslie Johnson, PhD, MPH, MLitt; Nida I. Shaik, PhD

- Previous contributions by: Neil K. Mehta, PhD (University of Michigan), Sue Ruedebusch, RN, CDE (Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute), and Paul Ciechanowski, MD, MPH (University of Washington)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali MK, Singh K, Kondal D, Devarajan R, Patel SA, Shivashankar R, … Tandon N (2016). Effectiveness of a Multicomponent Quality Improvement Strategy to Improve Achievement of Diabetes Care Goals: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med, 165(6), 399–408. 10.7326/m15-2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MK, Chwastiak L, Poongothai S, Emmert-Fees KMF, Patel SA, Anjana RM, … for the, I. S. G. (2020). Effect of a Collaborative Care Model on Depressive Symptoms and Glycated Hemoglobin, Blood Pressure, and Serum Cholesterol Among Patients With Depression and Diabetes in India: The INDEPENDENT Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama, 324(7), 651–662. 10.1001/jama.2020.11747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, & Subramanian SV (2011). Health care and equity in India. Lancet, 377(9764), 505–515. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1977). Self-Efficacy theory: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Wright C, Janice S, Turner A, & Hainsworth J (2002). Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A Review. Patient Educ Couns, 48, 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilello LA, Hall A, Harman J, Scuderi C, Shah N, Mills JC, & Samuels S (2018). Key attributes of patient centered medical homes associated with patient activation of diabetes patients. BCM Family Practice, 19(4). 10.1186/s12875-017-0704-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, & Handley MA (2009). Goal-setting for behavior change in primary care: an exploration and status report. Patient Educ Couns, 76, 174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher H, & Selby P (2018). Chapter 5: Patient Engagement and Empowerment: Key Components of Effective Patient-Centred Care In Velikova G, Fallowfield L, Younger J, Board RE, & Selby P (Eds.), Problem Solving in Patient-Centred and Integrated Cancer Care (pp 24–30). New York: Evidence-based Netowrks Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Coventry PA, Fisher L, Kenning C, Bee P, & Bower P (2014). Capacity, responsibility, and motivation: a critical qualitative evaluation of patient and practitioner views about barriers to self-management in people with multimorbidity. BMC Health Serv Res, 14(536). 10.1186/s12913-014-0536-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallivan J, Kovacs Burns KA, Bellows M, & Eigenseher C (2012). The many faces of patient engagement. J Participat Med, 4, e32. [Google Scholar]

- Graffigna G, Barello S, & Bonanomi A (2017). The role of Patient Health Engagement Model (PHE-model) in affecting patient activation and medication adherence: A structural equation model. PLoS One, 12(6), e0179865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks R, Overton V, & Parrotta CD (2015). When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Affairs, 34(3), 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T, Kakuma R, Palmer L, Martins J, Minas H, & Kermode M (2019). Are people-centred mental health services acceptable and feasible in Timor-Leste? A qualitative study. Health policy and planning, 34(Supplement_2), ii93–ii103. 10.1093/heapol/czz108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH (2003). Engaging health care consumers to improve the quality of care. Med Care, 41, 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, & Greene J (2003). What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences: fewer data on costs. Health Affairs, 32, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, & Mahoney E (2010). Toward a theory of patient and consumer activation. Patient Educ Couns, 78(3), 377–381. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney E, & Tusler M (2004). Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and Measuring Activation in Patients and Consumers. Health Serv Res, 39(4 PT 1), 1005–1026. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann-Broussard C, Armstrong G, Boschen M, & Somasundaram K (2017). A mental health training program for community health workers in India: impact on recognition of mental disorders, stigmatizing attitudes and confidence. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 10(1), 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- International Diabetes Federation. (2017). IDF Diabetes Atlas, 8th edition. Retrieved from http://www.diabetesatlas.org/across-the-globe.html

- Katon W, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman E, Young B, Rutter C, Oliver M, & McGregor M (2010). Integrating depression and chronic disease care among patients with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease: the design of the TEAMcare study. Contemp Clin Trials, 31(4), 312–322. 10.1016/j.cct.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal SK, Jhingan HP, Ramesh S, Gupta RK, & Srivastava VK (2004). India mental health country profile. Int Rev Psychiatry, 16, 126–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski AJ, Poongothai S, Chwastiak L, Hutcheson M, Tandon N, Khadgawat R, … Ali MK (2017). The INtegrating DEPrEssioN and Diabetes treatmENT (INDEPENDENT) study: Design and methods to address mental healthcare gaps in India. Contemporary clinical trials, 60, 113–124. 10.1016/j.cct.2017.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K (2006). Action Planning: A Call to Action. J Am Board Fam Med, 19, 324–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CK, & Bauman J (2014). Goal Setting: An Integral Component of Effective Diabetes Care. Curr Diab Rep, 14(509), 1–9. 10.1007/s11892-014-0509-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, & Wallerstein N (Eds.) (2008). Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. San Francsisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan V, Sandeep S Deepa R, Shah B, & Varghese C (2007). Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: Indian Scenario. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 125(3), 217–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik AD, Kallen MA, Walder A, & Street RL Jr. (2008). Improving hypertension in diabetes mellitus: the effects of collaborative and proactive health communication. Circulation, 117, 1361–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer A, & Kindig D (Eds). (2004). Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academic Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parchman ML, Zeber JE, & Palmer RF (2010). Participatory Decision Making, Patient Activation, Medication Adherence, and Intermediate Clinical Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: ASTARNet Study. Ann Fam Med, 8, 410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Xiao S, Chen H, Hanna F, Jotheeswaran AT, Luo D, Parikh R, Sharma E, Usmani S, Yu Y, Druss B, & Saxena S (2016). The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. The Lancet, 388(10063), 3074–3084. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00160-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R, & Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation. London, U.K: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, & Velicer WF (1997). The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12, 38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punton M, Vogel I, Lloyd R. Reflections from a Realist Evaluation in Progress: Scaling Ladders and Stitching Theory. 2016; CDI Practice Paper 18.

- Rothman AJ (2000). Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychology, 19 (1 suppl.), 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, & Mukhopadhyay B (2008). Perceived psychosocial stress and cardiovascular risk: observations among the Bhutias of Sikkim, India. Stress Health, 24, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shobhana R, Rao PR, Lavanya A, Padman C, Vijay V, & Ramachandran A (2003). Quality of life and diabetes integration among subjects with Type 2 diabetes. J Assoc Physicians India, 51, 363–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons LA, Wolever RQ, Bechard EM, & Snyderman R (2014). Patient engagement as a risk factor in personalized health care: a systematic review of the literature on chronic disease. Genome Medicine, 6(16). doi: 10.1186/gm533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal T, Sohal P, King-Shier KM, & Khan NA (2015). Barriers and Facilitators for Type-2 Diabetes Management in South Asians: A Systematic Review. PLoS One, 10(9), e0136202 10.1371/journal.pone.0136202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar G, & Madhu K (2002). Psychosocial and cultural issues in diabetes mellitus. Curr Sci, 83, 1556–1564. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar G, Madhu K, Veena S, Madhavi R, Sangeetha B, & Rani A (2007). Living with diabetes: Indian experience. Metab Syndr, 1, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, & Wagner EH (1997). Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med, 127(12), 1097–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, (1998). Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract, 1, 2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, & Schaefer J (2001). Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs, 20, 64–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, & Von Korff M (1996). Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank Quarterly, 74(4), 551–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N (2006). What is the Evidence on Effectiveness of Empowerment to Improve Health? Retrieved from Copenhagen, Denmark: www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74656/E88086.pdf

- Weaver LJ, & Hadley C (2011). Social pathways in the comorbidity between type 2 diabetes and mental health concerns in a pilot study of urban middle- and upper-class Indian women. Ethos, 39(2), 21–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbudzi E, Lo C, Ranasinha S, Kerr P, Polkinghorne K, Teede H, Usherwood T, Walker R, Johnson G, Fulcher G, & Zoungas S (2017). The association between patient activation and self-care practices: A cross-sectional study of an Australian population with comorbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Health Expect, 20(6), 1375–1384. 10.1111/hex.12577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.