ABSTRACT

Replication-dependent histone mRNAs are the only cellular mRNAs that are not polyadenylated, ending in a stemloop instead of a polyA tail, and are normally regulated coordinately with DNA replication. Stemloop-binding protein (SLBP) binds the 3′ end of histone mRNA, and is required for processing and translation. During Drosophila oogenesis, large amounts of histone mRNAs and proteins are deposited in the developing oocyte. The maternally deposited histone mRNA is synthesized in stage 10B oocytes after the nurse cells complete endoreduplication. We report that in wild-type stage 10B oocytes, the histone locus bodies (HLBs), formed on the histone genes, produce histone mRNAs in the absence of phosphorylation of Mxc, which is normally required for histone gene expression in S-phase cells. Two mutants of SLBP, one with reduced expression and another with a 10-amino-acid deletion, fail to deposit sufficient histone mRNA in the oocyte, and do not transcribe the histone genes in stage 10B. Mutations in a putative SLBP nuclear localization sequence overlapping the deletion phenocopy the deletion. We conclude that a high concentration of SLBP in the nucleus of stage 10B oocytes is essential for histone gene transcription.

This article has an associated First Person interview with the first author of the paper.

KEY WORDS: Histone locus body, Histone mRNA, Maternal mRNA, Drosophila oogenesis, Stemloop-binding protein, SLBP

Summary: Transcription of histone genes in stage 10B Drosophila oocytes to produce the maternal histone mRNAs requires high concentrations of SLBP, a protein normally required only for histone pre-mRNA processing.

INTRODUCTION

Replication-dependent histone mRNAs are the only known eukaryotic cellular mRNAs that are not polyadenylated. They end instead in a conserved stemloop which is formed by co-transcriptional endonucleolytic cleavage. Stemloop-binding protein (SLBP) binds to the stemloop and participates in histone pre-mRNA processing. SLBP remains with the processed histone mRNA, and accompanies it to the cytoplasm and is essential for histone mRNA translation (Whitfield et al., 2004; Sànchez and Marzluff, 2002; Sullivan et al., 2009). Thus SLBP is stoichiometrically required for accumulation of functional histone messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP) (Marzluff et al., 2008). In cultured Drosophila cells depleted of SLBP, histone genes are still transcribed at a normal rate, and the histone mRNAs are polyadenylated and the cells proliferate normally (Yang et al., 2009). Thus SLBP is required for co-transcriptional processing but not for transcription of the histone genes in Drosophila cells. In cycling cells, replication-dependent histone mRNAs are cell cycle regulated, being synthesized just prior to entry into S-phase and rapidly degraded at the end of S-phase. In contrast, the mRNAs for histone variants, such as H3.3 and H2a.Z are produced constitutively from polyadenylated mRNAs.

An initial challenge for all animals in early development is to provide sufficient histone proteins in the egg to remodel the sperm chromatin and also provide histones to package the replicating DNA as the embryo carries out the initial cell division cycles prior to activation of the zygotic genome. Different organisms have solved this problem in different ways (Marzluff et al., 2008). One developmental period when histone mRNA is not cell cycle regulated is in oogenesis and early embryogenesis in species that do not activate transcription during the early embryonic cell cycles. During the early embryonic cell cycles in many organisms, for example, insects, amphibians and sea urchins, there are rapid cycles consisting of S-phase followed by mitosis, which in Drosophila are as short as 5 min. The maternal histone mRNAs are stable during these cell cycles. At cycle 14 in Drosophila, the first G2 phase occurs, and the histone mRNAs, including the maternal and any newly synthesized zygotic histone mRNAs are degraded (Lanzotti et al., 2004b).

There are ∼100 copies of each of the five Drosophila melanogaster histone genes, organized in a tandemly repeated 5 kb unit containing one copy each of the four core histone genes and the histone H1 gene (Lifton et al., 1978; McKay et al., 2015; Bongartz and Schloissnig, 2019). Each of these histone genes contains a polyadenylation signal after the histone-processing signal. In cells with histone mRNA processing inhibited as a result of knockdown of factors required for histone pre-mRNA processing, polyadenylated histone mRNAs are produced (Wagner et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2011). The same alteration of histone gene expression occurs in flies with mutations in the histone-processing machinery (Godfrey et al., 2006, 2009; Burch et al., 2011; Sullivan et al., 2001).

The histone genes are present in a nuclear body, the histone locus body (HLB), which concentrates factors required for histone gene transcription and pre-mRNA processing. The core factors of the HLB are two large unstructured proteins, Multisex-combs (Mxc), the ortholog of mammalian NPAT, which is required for histone gene transcription, and FLASH, which is required for histone pre-mRNA formation (Marzluff and Koreski, 2017; Duronio and Marzluff, 2017). In cycling Drosophila cells histone gene expression is activated by phosphorylation of Mxc by cyclin E–Cdk2 as cells approach S-phase (White et al., 2011).

Drosophila provide a large maternal store of histone proteins and histone mRNAs that are synthesized in the nurse cells at the end of oogenesis, sufficient for embryos to develop until the 14th cell cycle even in the absence of zygotic histone genes (Günesdogan et al., 2010). During the development of the oocytes, the 15 nurse cells in the germarium undergo multiple cycles of endoreduplication during which histone mRNAs are synthesized in each S-phase and degraded as cells exit S-phase. At the end of the last nurse cell S-phase, before entering stage 10, the histone mRNAs are degraded. Histone gene transcription is then activated in the absence of DNA replication and the histone mRNAs are synthesized starting in stage 10B nurse cells and then dumped into the oocyte where they are translated into histone proteins. Both histone mRNA and protein are stored in the egg (Ruddell and Jacobs-Lorena, 1985; Ambrosio and Schedl, 1985; Walker and Bownes, 1998).

Here, we report that a region in SLBP distant from the RNA-binding and -processing domain is required to produce histone mRNAs at the end of oogenesis. Flies expressing either a deletion or point mutants in this region produce primarily normally processed histone mRNA but they also produce small amounts of polyadenylated histone mRNA in embryos, larvae and in ovaries. The animals are viable but the females are sterile, a maternal effect lethal due to the failure to deposit sufficient histone proteins and mRNAs into the egg. We show that this phenotype results from failure to accumulate enough SLBP in the nucleus of the nurse cells after stage 10 of oogenesis, which results in a failure to transcribe the histone genes at a high rate in the final stages of oogenesis.

RESULTS

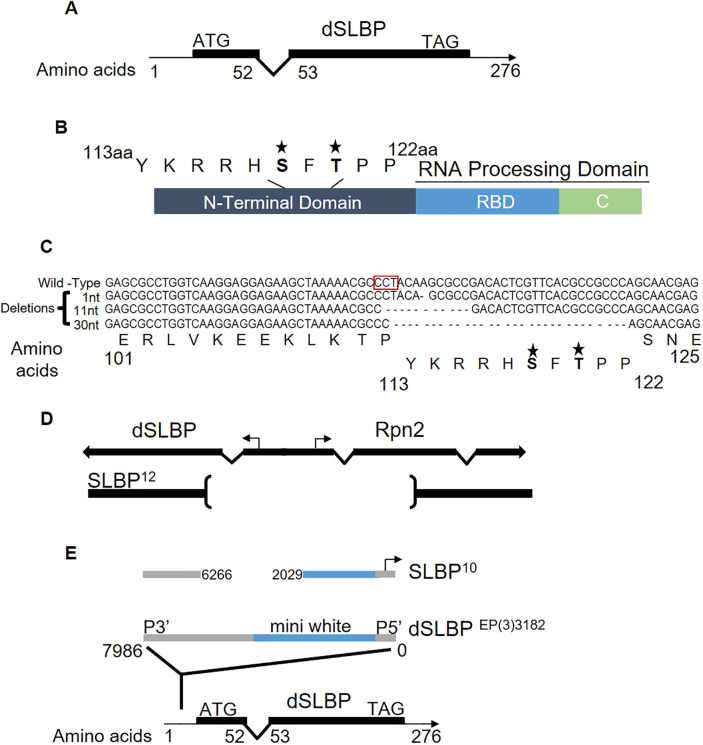

A schematic of the SLBP gene is shown in Fig. 1A, and a schematic of the domains of the SLBP protein are shown in Fig. 1B. The RNA-binding and -processing domains are sufficient for processing in vitro, while the N-terminal domain contains sequences required for translation of histone mRNA, import of the protein into the nucleus and that regulate the half-life of SLBP. The phenotype of a null mutant in SLBP is not known.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of SLBP structural domains, CRISPR mutants and excision alleles. (A) Drosophila SLBP contains two exons (black boxes) and one intron. (B) Domain structure of SLBP showing the RNA-processing domain composed of the RNA-binding domain and the C-terminus. The N-terminal domain contains two known phosphorylation sites in the SFTPP motif located between amino acids 113 to 122. (C) Sequence alignment of SLBP gene for each CRISPR deletion (1 nt, 11 nt and 30 nt). Note that the SFTPP motif is deleted in the 30 nt (10 aa) deletion. The stars indicate the phosphorylated amino acids within the sequence. (D) Diagram of the SLBP12 allele which contains a deletion extending from the coding region of both SLBP and Rpn2, including the bidirectional promoter (Sullivan et al., 2001). (E) Diagram of the SLBP10 allele which contains an insertion of part of the P element in the 5′ UTR region of SLBP (Sullivan et al., 2001). It is expressed from a cryptic promoter located near the P5′ end of the P element (Lafave and Sekelsky, 2011).

Mutants in the SLBP gene

To study the biological function of SLBP, we used FLY-CRISPR Cas9 and a guide RNA with a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site at amino acid (aa) 112 to create a null mutant of SLBP in Drosophila melanogaster. We obtained two frameshift mutations resulting from a 1 nt and an 11 nt deletion (Fig. 1C). We also obtained a 30 nt deletion, which deleted amino acids 113 to 122 (Fig. 1C). We also used two excision alleles previously characterized, SLBP12, a molecular null that removes a portion of the coding region of SLBP and the adjacent Rpn2 gene (Fig. 1D), and SLBP10, a hypomorph which contains a fragment of the P element in the 5′ UTR of SLBP (Fig. 1E). SLBP10 is a maternal effect lethal due to failure to produce enough histone mRNA at the end of oogenesis (Sullivan et al., 2001).

Phenotype of the SLBP-null mutant

SLBP is an essential factor for histone mRNA biogenesis and, not surprisingly, SLBP is essential for viability. Null mutants of SLBP in C. elegans die very early (<30 cells) in development due to failure to produce zygotic histone mRNA (Kodama et al., 2002; Pettitt et al., 2002). In Drosophila, cells with reduced levels of SLBP produce polyadenylated histone mRNAs since there is a cryptic polyadenylation site(s) 3′ of the stemloop (SL) in all Drosophila histone genes, which is utilized when histone pre-mRNA processing is blocked (Sullivan et al., 2001). There are large stores of maternal histone mRNA and protein stored in the egg, which are sufficient to support development through cycle 14 even in animals with the histone genes deleted (Günesdogan et al., 2010). In flies with mutated histone mRNA-processing factors, including SLBP, animals survive for different amounts of time due to perdurance of maternal factors as well as production of polyadenylated histone mRNA (Godfrey et al., 2009, 2006; Sullivan et al., 2001).

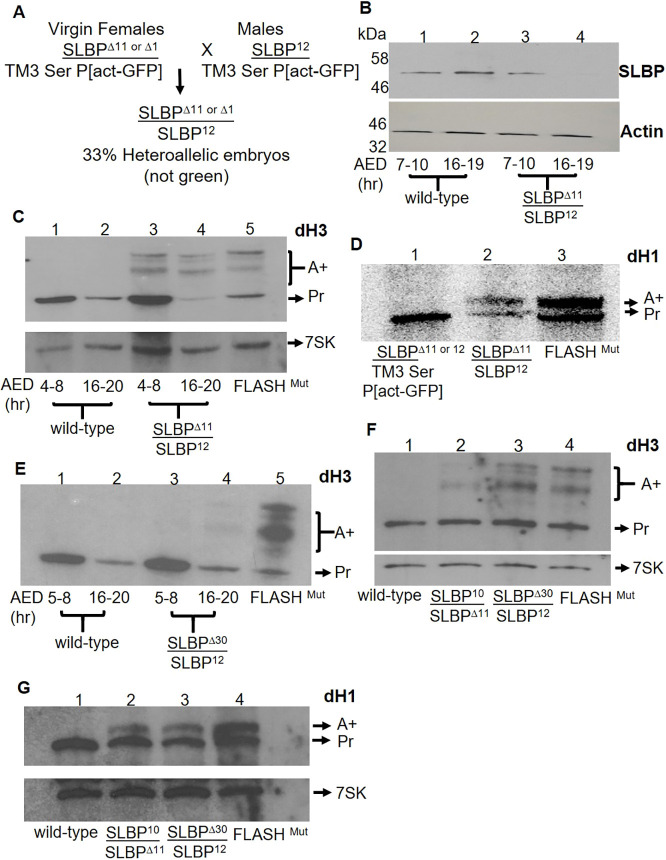

The original SLBP mutant we analyzed, SLBP15, was derived from an intact SLBP gene with a P element inserted in the 5′ UTR. This mutant retained most of the P element in the 5′ UTR, and failed to eclose, producing primarily polyadenylated histone mRNA in late larval stages (Sullivan et al., 2001; Godfrey et al., 2006). However SLBP15 is likely a hypomorph since there is a cryptic promoter at the end of the P element (Lafave and Sekelsky, 2011). We created a null allele of SLBP with the use of CRIPSR-Cas9. To study the role of SLBP in histone mRNA biogenesis during fly development, we tested the two candidate null alleles, SLBPΔ11 and SLBPΔ1. We crossed SLBPΔ11 or Δ1/TM3 Ser P[act-GFP] females with SLBP12/TM3 Ser P[act-GFP] males (Fig. 2A), and also carried out the reciprocal cross. The null mutant embryos were selected based on the absence of GFP. The null mutants SLBPΔ11 and SLBPΔ1 died as first-instar larvae when they were present together with a deficiency of SLBP, SLBP12. We carried out molecular analyses with SLBPΔ11. We determined how long the maternal supply of SLBP protein lasted using an affinity-purified antibody raised against full-length SLBP, which gave a single band in a western blot. Western blot analysis of embryos shows that maternal SLBP declined during embryogenesis and that, in the mutants, SLBP was almost undetectable by 16–19 h after egg deposition (AED) (Fig. 2B, lane 4). We also analyzed Drosophila Histone H3 (dH3) mRNAs by northern blotting (Fig. 2C), using 7SK RNA, a small nuclear RNA of ∼350 nts, as an internal control. Both properly processed histone H3 mRNA (Pr) as well as polyadenylated misprocessed mRNAs, caused by multiple cryptic polyadenylation sites, were formed in the SLBP mutants (Lanzotti et al., 2002). SLBPΔ11 mutant embryos aged for 4–8 h begin to accumulate polyadenylated dH3 mRNA, indicating that histone pre-mRNA processing was already inefficient at this time (Fig. 2C, lane 3). By 16 h of embryogenesis, the majority of the dH3 mRNA was polyadenylated (Fig. 2C, lane 4), although the total amount of H3 mRNA was much less than in early embryogenesis. RNA from FLASH mutant larvae (FLASHMUT) was used as positive control for polyadenylated histone mRNA (Fig. 2C, lane 5) (Tatomer et al., 2016). We also analyzed histone mRNA present in first-instar larvae, and found that the heteroallelic larvae contained both polyadenylated and processed histone H1 mRNA with the polyadenylated mRNA predominating (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

An SLBP null mutant produces polyadenylated histone mRNA in early development. (A) SLBPΔ11 or Δ1/TM3 Ser P[act-GFP] females were mated with SLBP12/TM3 Ser P[act-GFP] males, and the mutant embryos not expressing GFP were selected starting 4 h after egg deposition when GFP was expressed. Since embryos with two TM3 balancers are not viable, 33% of surviving embryos expressed GFP. RNA or protein was extracted from GFP negative SLBPΔ11/SLBP12 (null mutant) embryos or a parallel group of wild-type embryos and histone mRNA was analyzed by both western and northern blotting. A total of 20 embryos were pooled to prepare samples for each lane of B–E. Internal controls (actin for western blots and 7SK RNA in northern blots) were measured in each experiment. Results in B–G are representative of at least three biological replicates except for D, which is representative of two biological replicates. (B) Western blot analysis of wild-type embryos (lanes 1 and 2) and null mutant embryos (lanes 3 and 4) collected from 7–10 h and 16–19 h AED. There are much lower levels of SLBP in the mutant embryos by 16–19 h AED as the maternal supply is depleted. This affinity purified antibody recognizes a single band on a western blot which is abolished by treating cultured Drosophila cells with dsRNA against SLBP (data not shown). (C) RNA was prepared from wild-type (lanes 1 and 2) and null mutant embryos (lanes 3 and 4) from 4–8 h and 16–20 h AED and analyzed by northern blotting for histone H3 mRNA. Lane 5 is analysis of RNA from a FLASH mutant that expresses both processed (Pr) and polyadenylated (A+) histone mRNA (Tatomer et al., 2016). The band labeled Pr is properly processed RNA, and the bands labeled A+ are polyadenylated histone H3 mRNAs formed using one of several polyA signals in the region after the H3 gene (Lanzotti et al., 2002). (D) First-instar larvae were collected from sibling GFP-positive heteroallelic (SLBPΔ11/TM3 or SLBP12/Tm3; phenotypically wild-type) (lane 1) and heteroallelic (GFP negative) null mutants SLBP12/SLBPΔ11 (lane 2); 10 larvae were pooled in each lane and total RNA was analyzed by northern blotting for histone H1 mRNA. Lane 3 is RNA from the FLASH mutant. The filter was analyzed using a PhosphorImager. A single polyadenylation site is present after the histone H1 gene (Lanzotti et al., 2002). (E) RNA from wild-type (lanes 1 and 2) and heteroallelic embryos SLBPΔ30/SLBP12 (lanes 3 and 4) were collected from 5–8 and 16–20 h (AED) and analyzed by northern blotting. Small amounts of polyadenylated H3 mRNA was detected in 16-20 h SLBPΔ30 embryos (lane 4). Lane 5 shows the RNA from the FLASH mutant. (F,G) Third-instar larvae (10 larvae were pooled for each lane) were collected from wild-type (lane 1) and heteroallelic (GFP negative) mutants SLBP10/SLBPΔ11 (lane 2), or SLBPΔ30/SLBP12 (lane 3). Equal amounts of RNA were probed for dH3 (F) and dH1 (G) together with 7SK RNA as a control. Lane 4 is the FLASH mutant RNA.

The 30 nt deletion is maternal effect lethal

Similar genetic analyses were performed to ask whether the 30 nt (10 aa) deletion (SLBPΔ30) was viable over the deficiency of SLBP, SLBP12. Flies containing one allele of SLBPΔ30, expressing only the 30 nt (10 aa) deletion, were viable but the females were sterile (maternal effect lethal). Previously, we had identified a hypomorphic allele of SLBP, SLBP10, which had a similar maternal effect lethal phenotype, due to failure to provide sufficient maternal supply of histone mRNA or protein in the egg (Sullivan et al., 2001). SLBPΔ30 females showed a similar phenotype to SLBP10 females. Both mutants laid similar amounts of eggs to the wild-type flies, but none of the embryos developed past the syncytial stage, and they died as a result of mitotic defects in the syncytial cycles (Fig. S1). The SLBP10 mutant has an insertion from the initial P element remaining in the 5′ UTR (Fig. 1E) but the coding region of the gene is intact, and it expresses less SLBP than wild-type flies.

The SLBPΔ30 protein has a 10 aa deletion, between the N-terminus and the RNA-binding domain (Fig. 1B). Processing in vitro requires only the RNA-binding domain and the C-terminus of SLBP (Dominski et al., 2002), suggesting that the SLBPΔ30 protein is active in processing. Two phosphorylation sites were deleted in SLBPΔ30, a threonine residue of unknown function, which is phosphorylated on ∼30% of the molecules (Borchers et al., 2006) and a serine residue, which is a Chk2 substrate (Iampietro et al., 2014). The Chk2 phosphorylated form plays a role in destruction of SLBP in defective nuclei during the syncytial stages of development.

Expression of polyadenylated histone mRNA in embryos and larvae of SLBPΔ30

We examined whether the hypomorphic mutants also produce polyadenylated histone mRNAs. We prepared total RNA from different times AED in embryogenesis and third-instar larvae, and analyzed it by northern blotting. Only small amounts of polyadenylated histone H3 mRNA was detected in the SLBPΔ30 mutant by the end of embryogenesis (Fig. 2E, lane 4), but some polyadenylated histone H3 and H1 mRNAs were produced in third-instar larvae in both the SLBP10 and SLBPΔ30 mutants, although the majority of the histone mRNAs were properly processed (Fig. 2F,G, lanes 2 and 3). Thus the SLBPΔ30 mutant is capable of processing histone mRNA in vivo, although processing is not completely efficient.

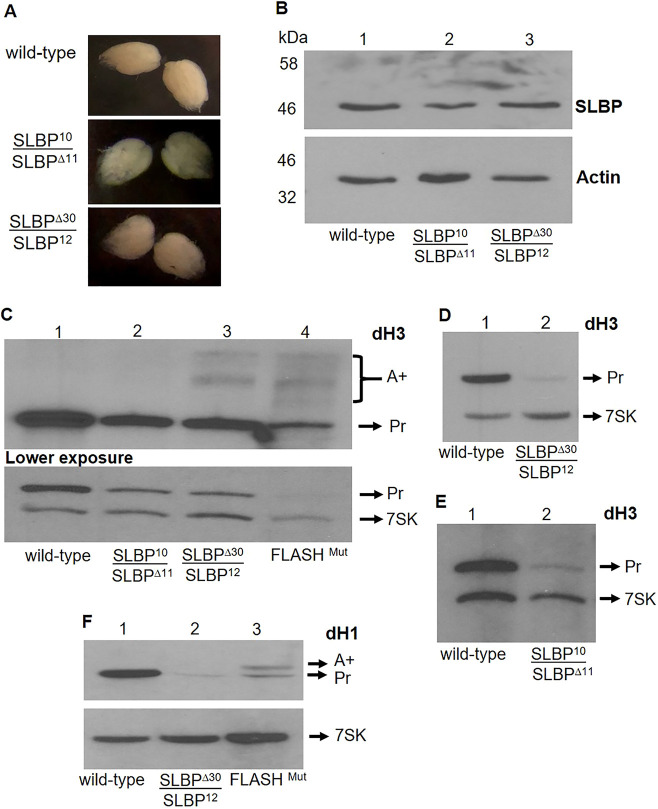

Effect of hypomorphic mutants on ovary function

The ovaries of SLBP10 and SLBPΔ30 females were normal in appearance and similar in size to wild-type ovaries (Fig. 3A). The mutant ovaries had normal looking germaria, and the different stages of egg chamber maturation were similar in both the mutant and wild-type animals. We examined the SLBP protein levels in both SLBPΔ30 and SLBP10 ovaries by western blotting and histone mRNA levels by northern blotting. Ovaries expressing only SLBP10 contained a lower amount of SLBP protein compared to wild type, as judged relative to the levels of actin (Fig. 3B, lane 2). In contrast, SLBPΔ30 ovaries contained similar levels of SLBP to wild type (Fig. 3B, lane 3). A northern blot analysis showed reduced levels of dH3 mRNA in ovaries from both mutants (Fig. 3C, lanes 2 and 3). The SLBPΔ30 mutant also expressed small amounts of polyadenylated dH3 mRNA as well as properly processed mRNA (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

SLBP and histone mRNA levels in ovaries differed among SLBP10, SLBPΔ30 and wild-type flies. (A) Females were aged for 4–6 days, and the ovaries from wild-type, SLBP10 and SLBPΔ30 were dissected and photographed. They ovaries are similar in size in all three flies. (B) Twenty ovaries from ten SLBP10 and SLBPΔ30 heteroallelic females and wild-type females were pooled and analyzed for SLBP protein by western blotting using actin as a loading control. Results are representative of results with three biological replicates, with SLBP levels reduced in SLBP10 but not in SLBPΔ30 mutants relative to actin. (C) Histone H3 mRNA from 10 ovaries from SLBPΔ30 and SLBP10 was analyzed by northern blotting for H3 mRNA using 7SK RNA as a loading control. Lane 4 is RNA from the FLASH mutant (Fig. 2C) used a positive control for polyA RNA. The results are representative of three biological replicates with histone mRNAs reduced in SLBPΔ30 and SLBP10 relative to wild-type. (D–F) Twenty pooled embryos collected from 30 to 45 min (AED) from SLBPΔ30 (D), SLBP10 (E) and wild-type females and analyzed for dH3 mRNA by northern blotting. The results were similar in two biological replicates. (F) dH1 mRNA was analyzed from the same RNA sample from SLBPΔ30 embryos with FLASHmut as a control. During this time the embryo only contains the maternal histone mRNA supply loaded into the egg.

SLBPΔ30 females deposit very low levels of histone mRNAs into eggs

It is known that histone mRNAs (Ambrosio and Schedl, 1985; Ruddell and Jacobs-Lorena, 1985; Walker and Bownes, 1998) and proteins are synthesized at the end of oogenesis and loaded into the egg. These proteins and mRNAs are utilized during the syncytial stages of embryogenesis prior to activation of the zygotic genome, since embryos lacking any histone genes develop through cycle 14 (Günesdogan et al., 2010). We previously showed that eggs from SLBP10 mutant ovaries contain ∼10% as much histone mRNA (Lanzotti et al., 2002) as wild-type embryos. We determined whether the maternal supply of histone mRNA was affected in embryos laid by females expressing SLBPΔ30 by northern blotting. The amount of histone H3 and histone H1 mRNA in embryos 30–45 min AED were determined by northern blotting (Fig. 3D–F). Only very small amounts of each RNA were detected in the eggs from SLBPΔ30 embryos, similar to the small amount of H3 mRNA present in the SLBP10 eggs (Fig. 3E).

Expression of histone mRNAs during different stage of oogenesis

Development of the oocyte occurs within a germarium in the ovary. A germline stem cell undergoes four cycles of division resulting in 16 cells. One of these cells becomes the oocyte, while the other 15 cells become nurse cells. The nurse cells undergo multiple rounds of endoreduplication, resulting in them having, ultimately, a DNA level of about 1000C (Hammond and Laird, 1985). The nurse cells and oocyte are surrounded by a layer of somatic follicle cells whose numbers dramatically increase during egg chamber maturation. Thus, western and northern blots of the whole ovary primarily detect the mRNAs and proteins in the oocyte, nurse cells and follicle cells.

To study details of histone mRNA metabolism in the developing egg chamber, we performed single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) using a collection of fluorescently labeled single-strand DNA oligonucleotides complementary to the coding region of histone H3 (Hur et al., 2020). Consistent with previous results, in the germarium and early stage egg chambers, H3-coding in situ signal could be observed in the cytoplasm of some but not all cells (Fig. S2A,B) (Tatomer et al., 2016). Early-stage egg chambers in both the SLBP10 (Fig. S2C) and SLBPΔ30 (Fig. S2D) mutants developed normally and were similar to the wild-type in having both cytoplasmic histone mRNA and nuclear foci in some cells. Co-staining with FLASH, a component of the HLB and the histone-coding probe, showed that the nuclear foci were HLBs, and these results are indicative of ongoing histone gene transcription at the HLB (Fig. S2C′,D′).

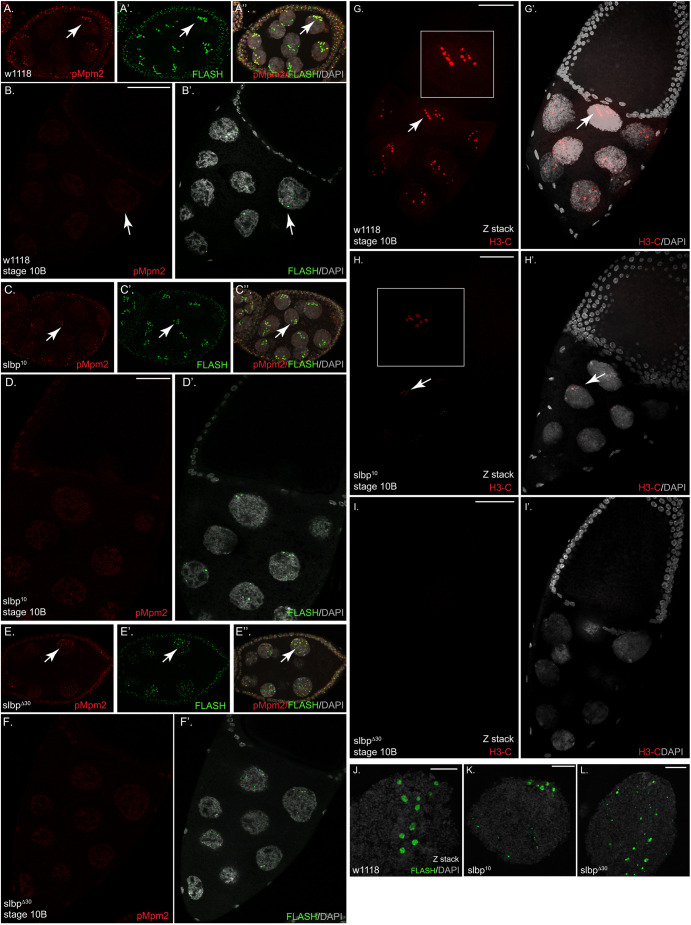

In order to confirm that these cells correspond to those that are in S-phase, egg chambers were stained with an antibody against FLASH, and the mpm2 antibody, which binds to phosphorylated Mxc, to identify S-phase cells (White et al., 2007, 2011). Although FLASH-positive nuclear foci could be detected in all cells, only a fraction of these nuclear foci were positive for mpm2 in wild-type cells (Fig. 4A–A″). The mpm2-positive cells correspond to follicle cells and endoreduplicating nurse cells that are in S-phase.

Fig. 4.

Histone mRNA expression is defective in SLBP10 and SLBPΔ30 stage 10B egg chambers. (A) At least 20 flies (40 ovaries) were dissected and processed for each genotype. An early stage wild-type egg chamber stained with the mpm2 (A, pMpm2, red) and FLASH (A′, green) antibodies. A merged image along with DAPI (gray) is shown in A″. Arrows indicate a nucleus with mpm2-positive HLBs. (B) A wild-type stage 10B egg chamber stained with mpm2 (B, red) and FLASH (B′, green) is shown. The arrow indicates nuclear FLASH foci. Note that there is some diffuse mpm2 staining of the nucleoplasm, which also reacts with some other nuclear phosphoproteins, consistent with the mpm2 antibody penetrating the stage 10B oocytes. (C) An early stage SLBP10 egg chamber stained with the mpm2 (C) and FLASH (C′) antibodies is shown. A merged image along with DAPI is shown in C″. Arrows indicate a nucleus with mpm2-positive HLBs. (D) A SLBP10 stage 10B egg chamber stained with mpm2 (D) and FLASH (D′) is shown. (E) An early stage SLBPΔ30 egg chamber stained with the mpm2 (E) and FLASH (E′) antibodies is shown. A merged image along with DAPI is shown in E″. Arrows indicate mpm2-positive HLBs. (F) A SLBPΔ30 stage 10B egg chamber stained with mpm2 (F) and FLASH (F′) is shown. (G–I) Stage 10B egg chambers from wild-type (G), SLBP10 (H) or SLBPΔ30 (I) processed for in situ hybridization using probes against the H3 coding region are shown (H3-C, red). The images represent a Z-stack. A merged image with DAPI is shown in G′, H′ and I′. Arrows indicate nuclear H3 foci present in all nuclei in wild-type 10B egg chambers. There are a small number of nuclei in SLBP10 nurse cell nuclei which have weak foci (arrow). A magnified view of the region indicated by the arrow in G and H is also shown. (J–L) A Z-stack of a single nurse cell nucleus from wild-type (J), SLBP10 (K) or SLBPΔ30 (L) stained with the FLASH antibody (green) and counter-stained with DAPI (gray) is shown. Scale bars: 50 μm (A–I); 10 μm (J–L).

Histone mRNAs are expressed from mpm2-negative HLBs for deposition into the egg

Endoreduplication of nurse cells is complete by stage 10, and there is no detectable histone mRNA in the nurse cell cytoplasm at this stage. FLASH-positive nuclear foci (HLBs) were detected in nurse cells of stage 10B egg chambers. There were 7–15 large HLBs in each stage 10B nurse cell nucleus, each one likely containing ∼2000 histone gene repeats (10,000 total histone genes). Large clusters of histone genes were previously reported at stage 10B using in situ hybridization (Hammond and Laird, 1985). Histone gene transcription was active in all the nurse cells in stage 10B, as visualized by in situ hybridization with the H3-coding region probe, which detected nascent transcripts at all the HLBs in the stage 10B nurse cells (Fig. 4G).

Surprisingly, the HLBs in most of the nurse cell nuclei did not stain with mpm2 in the wild-type stage 10 HLBs; 86% were negative for mpm2 (Fig. 4B,B′). In the 14% of wild-type stage 10B oocytes that were positive for mpm2, all the HLBs were positive (Fig. S2E,E′,E″). Despite not being in S-phase, all these cells displayed abundant H3-coding in situ signal (Fig. 4G,G′) at nuclear foci. Thus, histone gene expression is turned on in all stage 10B nurse cells in the absence of DNA replication, and in the great majority of these egg chambers, the HLBs are mpm2 negative. We observed positively and negatively stained 10B egg chambers on the same slide, and always saw staining of S-phase cells with mpm2 in the earlier stages, suggesting that the Mpm2 antibody penetrated the stage 10B egg chambers. In support of mpm2 penetrating the stage 10B egg chambers, similar levels of nucleoplasmic mpm2 staining was seen in the stage 10B nurse cells that are negative (Fig. 4B) and positive (Fig. S2E) for mpm2 staining of HLBs.

We next compared histone mRNA expression between wild-type and SLBP mutant egg chambers by in situ hybridization. Histone mRNA expression in the germarium and early stage egg chambers was similar between wild-type, SLBP10 and SLBPΔ30 mutants (Fig. S2C,D). Starting in stage 10B egg chambers, the mutants differed markedly from the wild type. Although abundant histone transcription foci could be detected in the stage 10B nurse cells of wild-type egg chambers, transcription foci were greatly reduced (SLBP10) or not detectable (SLBPΔ30) in the SLBP mutants (Fig. 4H,I). The SLBP10 mutant displayed a weaker phenotype, and in these egg chambers some transcription foci could be detected (Fig. 4H,H′). However, the level of H3-coding in situ signal at the nuclear foci was significantly reduced in comparison to wild-type (Fig. 4H,H′). SLBPΔ30 mutants displayed a more severe phenotype and the in situ signal was not detectable in most stage 10B egg chambers (Fig. 4I,I′).

The HLBs also differed in morphology in the stage 10B nurse cells in the wild type and the two mutants. The FLASH foci were larger and there were fewer of them in the wild-type stage 10B egg chambers, while in the two mutants, the foci were smaller and there were many more per cell in both mutants, with the SLBPΔ30 being more severely affected than the SLBP10 mutants (Fig. 4J–L; see also Fig. 8L). These results suggest that the HLBs are not well organized in the mutants, as the increased number of smaller foci likely reflect multiple foci each with fewer histone genes associated with each focus.

Fig. 8.

SLBP and HLB defects in the SLBPARA germline. Ten flies (20 ovaries) for each genotype were processed for this experiment. Egg chambers from wild-type (A,B,C,C′) and SLBPARA (D,E,F,F′) mutant ovaries were processed for immunofluorescence using the antibody against SLBP (green). C′ and F′ are DAPI counterstained to reveal nuclei. In contrast to wild-type, SLBP is not enriched in the nuclei of SLBPARA mutants in either the germline or follicle cells. Quantification of this phenotype is shown in Fig. 6G. Ovaries from these strains were also processed using an antibody against FLASH (red) to reveal the HLB. The samples were counterstained with DAPI (gray, G-K). Nuclei in stage 10B wild-type egg chambers contain 8 to 15 large HLBs (G,H,L), whereas in SLBPARA mutants HLBs are much smaller and much more numerous (I,J,L). The HLBs in the follicle cells of SLBPARA mutants were normal (K). A similar, but milder phenotype for HLB number and size is seen for SLBP10 and SLBPΔ30 mutants (L). Scale bars: 50 μm (A,D); 25 μm (B,C,F,K); 10 μm (E,G,H,I,J).

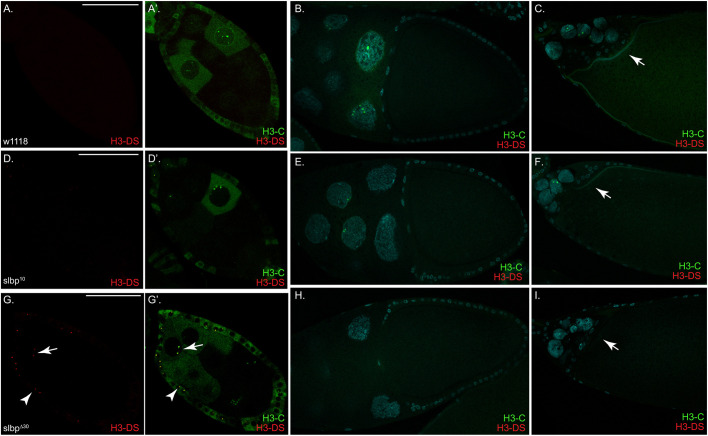

We determined whether histone mRNA processing was disrupted in the germarium of SLBP mutants. Egg chambers were hybridized with two probes, the H3-coding probe (H3-C) and a probe that hybridizes to a region downstream of the coding region (H3-DS). This region is not expressed when nascent histone transcripts are rapidly processed coupled with transcription termination, but is expressed in mutants where processing is less efficient or occurs with slower kinetics, allowing transcription past the normal transcription termination site (Tatomer et al., 2016; Lanzotti et al., 2002). In early stage wild-type and SLBP10 mutant egg chambers, H3-C signal was observed in nuclear foci, and also diffusely in the cytoplasm of nurse cells and follicle cells in S-phase. Minimal signal was detected with the H3-DS probe in the wild-type or SLBP10 egg chambers (Fig. 5A,A′,D,D′). By contrast, in SLBPΔ30 mutants, H3-downstream probe signal was observed in some of these egg chambers. Often signal from the downstream probe was detected as foci in follicle cell nuclei (Fig. 5G,G′, arrowhead). Occasionally signal from the downstream probe could also be detected as foci within nurse cell nuclei (Fig. 5G,G′, arrow).

Fig. 5.

Misprocessed histone mRNA can be detected in early-stage SLBPΔ30 egg chambers. Twenty flies (40 ovaries) were processed for each genotype shown. Egg chambers from wild-type (A–C), SLBP10 (D–F) and SLBPΔ30 (G–I) mutant ovaries were processed for in situ hybridization using probes against the coding region of H3 mRNA (H3-C, green) and against a region downstream of the coding region (H3-DS, red). A, D and G are early stage egg chambers; B, E and H are stage 10B, and C, F and I are late stage egg chambers. H3-DS signal was detected in early stage SLBPΔ30 egg chambers. The H3-DS signal was most often seen in follicle cells (G, arrow head) but could occasionally also be observed in the nurse cell nuclei of SLBPΔ30 mutant egg chambers (G, arrow). Arrows in C, F and I are the band of follicle cells that separate the egg chamber. Scale bars: 50 μm.

At stage 10B, H3-coding signal, but not H3-downstream signal, could be detected in wild-type egg chambers (Fig. 5B), both as transcription foci in nuclei and in the cytoplasm near the oocyte. At the same stage, both mutants displayed reduced H3-coding signal, both in nuclear foci and the cytoplasm. Signal from H3-DS was also minimal in the wild-type and both mutants (Fig. 5E,H). This data is consistent with the defect in histone gene expression in the mutants in stage 10B being at the level of histone gene transcription.

Cytoplasmic histone mRNA accumulated in the nurse cell cytoplasm at stage 10B, and, as oocyte development continued, histone mRNAs were detected at the nurse-cell–oocyte boundary and accumulating in the oocyte. As nurse cell dumping continues, the nurse cells continue to have transcription foci and large amounts of histone mRNA accumulates in the wild-type oocyte (Fig. 5C), but much lower amounts of histone mRNA accumulate in the oocyte in the SLBP10 and SLBPΔ30 mutants (Fig. 5F,I), in agreement with the northern blot results (Fig. 3D–F). Transcription of histone genes continued in the nurse cell nuclei into late oogenesis, with transcription continuing in healthy nuclei even after some of the nurse cell nuclei had undergone apoptosis, which is initiated asynchronously late in oogenesis (Foley and Cooley, 1998; Pritchett et al., 2009).

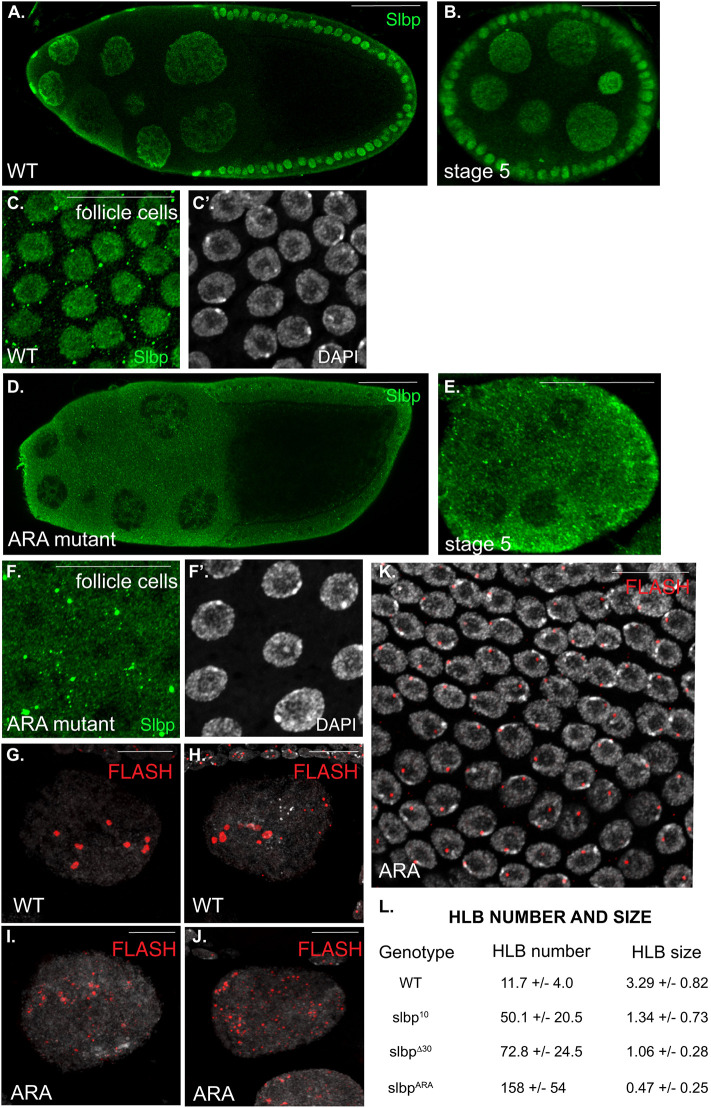

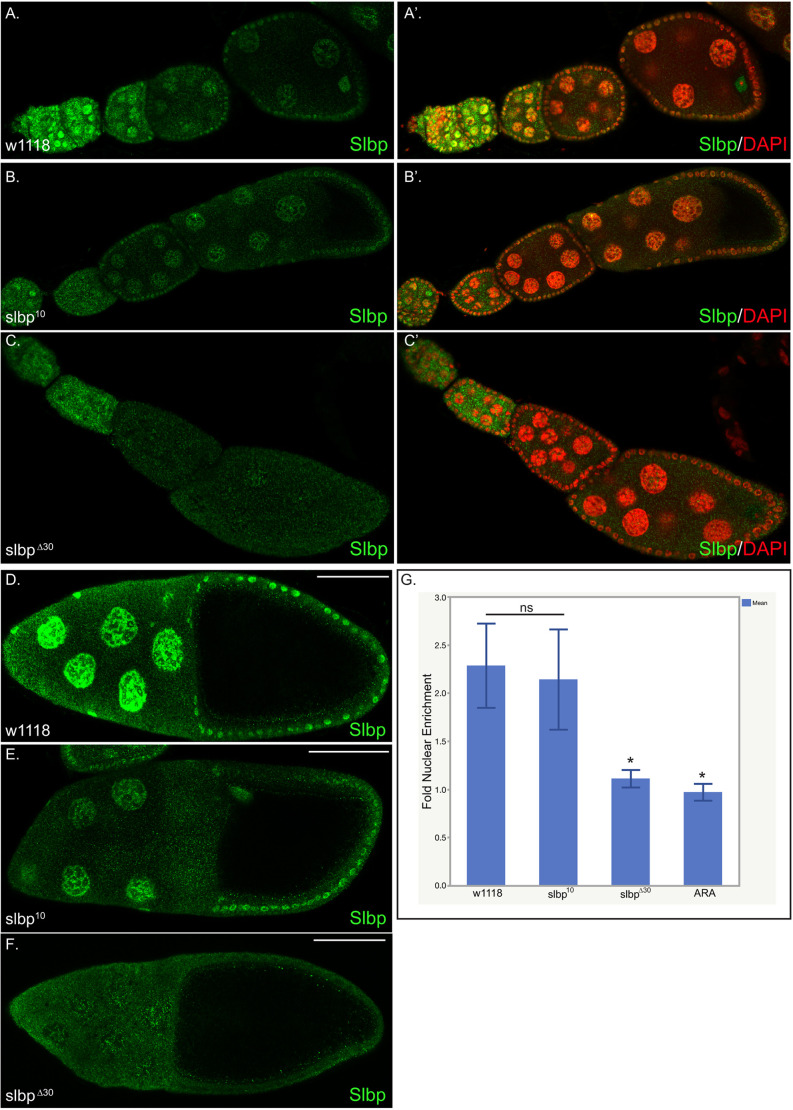

SLBP is mislocalized in SLBPΔ30 mutants

Western blot analysis indicated that SLBP protein was expressed in normal amounts in ovaries from SLBPΔ30 mutants, but lower amounts were expressed in the SLBP10 mutant (Fig. 3B). In order to more precisely characterize the defect in SLBP metabolism, we examined the localization of SLBP in wild-type and mutant ovaries by immunofluorescence. SLBP was detected in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments in wild-type egg chambers, consistent with it being bound to cytoplasmic histone mRNA as well as being concentrated in the nucleus for histone pre-mRNA processing, as it is in mammalian cells (Erkmann et al., 2005). The fluorescence signal was reduced in egg chambers expressing an shRNA against SLBP (Fig. S3) indicating that the antibody specifically detected SLBP by immunofluorescence. SLBP was present in significantly higher concentrations in the nuclei of both nurse cells and follicle cells during all early stages of oogenesis as well as in stage 10B (Fig. 6A). Note that SLBP is present in all nurse cell nuclei, whether or not they are in S-phase, suggesting that its amounts do not change during the cell cycle during nurse cell endoreduplication (Fig. 6A). In the SLBP10 mutant, the level of SLBP protein was reduced in early-stage and stage 10B egg chambers, although its localization was normal and the nuclear enrichment of SLBP was still evident in the SLBP10 mutant background (Fig. 6B,E).

Fig. 6.

SLBP is mislocalized in SLBPΔ30 egg chambers. Twenty flies (40 ovaries) were processed for each genotype. Egg chambers from wild-type (A,A′,D), SLBP10 (B,B′,E) and SLBPΔ30 (C,C′,F) mutant ovaries were processed for immunofluorescence using an antibody against Slbp (green). The images shown in A′, B′ and C′ are counterstained with DAPI (red). A–C show early stage egg chambers and D–F show a stage 10B egg chamber. (G) Relative enrichment of SLBP is nuclei of ten stage 10B egg chambers were quantified (mean±s.d.) for each genotype as well as the ARA mutant. In wild-type and SLBP10 mutants, SLBP protein is enriched within the nucleus (G). Note there is less SLBP present in SLBP10 egg chambers. There is no enrichment of SLBP in the nuclei of SLBPΔ30 mutants in the nurse cells or follicle cells (G). *P<0.05; ns, not significant (unpaired t-test). Scale bars: 50 μm.

In contrast, although the level of SLBPΔ30 protein was similar to that of the wild type, the nuclear enrichment of SLBP in nurse cells and follicle cells was greatly reduced in SLBPΔ30 mutant egg chambers (Fig. 6C,G). In particular, in the stage 10B egg chambers, SLBP was present at similar concentrations in the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Fig. 6G). Collectively, these results suggest that a high concentration of nuclear SLBP is required for transcription of the histone genes in stage 10B egg chambers.

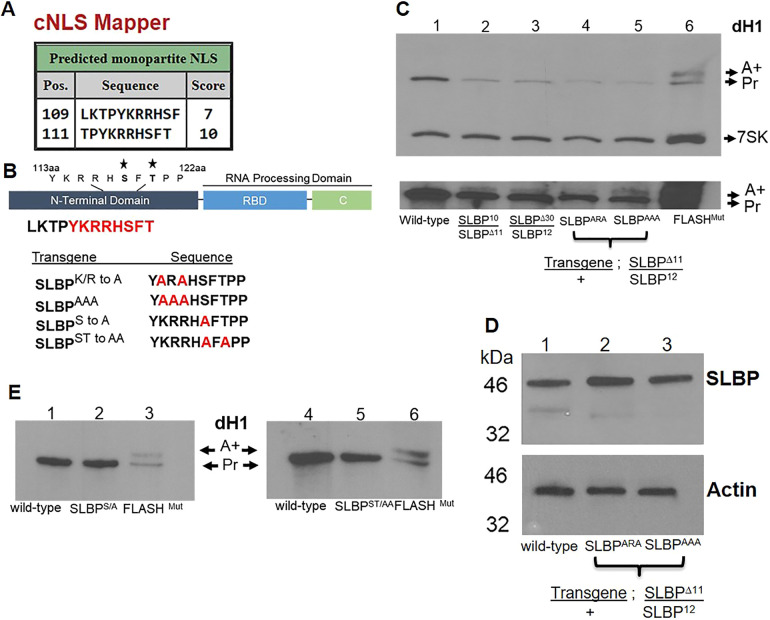

Basic amino acids in the 10 aa region are required for maternal histone mRNA deposition

The 10 aa region that was deleted from SLBP in SLBPΔ30 contains a cluster of basic amino acids, KRR, at its N-terminus and the sequence SFTPP, in which both the serine and threonine residues have been identified as phosphorylation sites, and which is similar to the sequence involved in regulating mRNA half-life in vertebrate SLBPs (Zheng et al., 2003). Since there is a defect in SLBP nuclear concentration in the SLBPΔ30 mutant, we used NLS-mapper (http://nls-mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi-bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi; Kosugi et al., 2009) to identify potential nuclear localization sequences in SLBP. Only two overlapping sequences were identified, both of which included the KRR deleted in the SLBPΔ30 mutant (Fig. 7A). We mutated both the KRR sequence and the two phosphorylation sites (Fig. 7B). Genetic analyses were performed to ask whether these point mutants rescued the null background SLBPΔ11/SLBP12 (Fig. S4). All of the point mutants of the SLBP gene were integrated by recombinase mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) at site 25C in the 2nd chromosome (Groth et al., 2004; Bateman et al., 2006). The complete SLBP gene (including promoter and 3′ flanking sequences) was used (Lanzotti et al., 2004a) and integration of the wild-type SLBP gene at this site completely rescued the null mutant phenotype, with no detectable production of polyadenylated histone mRNA (J.P.-B., unpublished results).

Fig. 7.

Mutants in the basic region of the 10 aa deletion are maternal effect lethal and phenocopy the SLBPΔ30 mutant. (A) A predicted nuclear localization signal overlaps with the 10 aa deletion. (B) Schematic of the SLBP structure with the point mutants in the 10 aa deletion and phosphorylation site are shown below. (C) Total RNA was prepared from ovaries of wild-type, SLBP10, SLBPΔ30 and the SLBPARA and SLBPAAA mutants, and analyzed by northern blotting for histone H1 mRNA with 7SK as an internal control. Lane 6 is the control FLASH mutant RNA. The polyadenylated histone H1 mRNA is detected in the darker exposure in each mutant. (D) Total protein from ovaries of wild-type, and the SLBPARA and SLBPAAA mutants, was analyzed by western blotting for SLBP, with actin used as the internal control. (E) Total RNA from wild-type ovaries (lanes 1 and 4) and the SLBPS/A (lane 2) and SLBPST/AA (lane 5) mutants was analyzed by northern blotting for histone H1 mRNA. Lanes 3 and 6 are the FLASH mutant RNA. Blots are representative of two independent experiments. Pr, properly processed RNA; A+, polyadenylated histone.

Mutation of the KRR region to ARA or AAA reproduced the maternal effect lethal phenotype, with the females laying eggs which never hatched. In addition these mutants had reduced amounts of histone mRNA in the ovaries, as was also the case for SLBP10 and SLBPΔ30 mutant (Fig. 7C). Small amounts of polyadenylated histone H1 mRNA was also detected in all the mutants. Western blots showed that, as with SLBPΔ30, there were similar amounts of SLBP in the ovaries from these two mutants (Fig. 7D) to that in ovaries from wild-type animals. These results are consistent with the interpretation that the defect in all of these flies with the maternal effect lethal mutant phenotype is due to a reduced amount of SLBP in the nuclei of stage 10B oocytes.

We also constructed SLBP mutants where we changed the SFTPP sequence to AFTPP and AFATP (Fig. 7B). In contrast to mutations of the basic region, mutation of the serine or both the serine and threonine in the SFTPP sequence had no effect on viability or fertility. These mutant SLBPs rescued the null mutations, restored viability, and both males and females were fertile. There was also no polyadenylated histone mRNA detected in flies expressing only the mutant SLBPs (Fig. 7E).

We analyzed the ARA mutant egg chambers by confocal microscopy, both for HLBs and for localization of SLBP. In wild-type egg chambers, SLBP was concentrated in nuclei, both in stage 10B as well as stage 5 of oogenesis, during nurse cell endo- reduplication (Fig. 8A,B). It was also concentrated in nuclei of follicle cells (Fig. 8C). In contrast in the ARA mutant SLBP was clearly spread uniformly throughout the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm at the same stages, including during nurse cell endoreduplication and in follicle cells (Fig. 8D,E; Fig. 6G).

We also analyzed HLBs in parallel wild-type and ARA mutant egg chambers. In wild-type stage 10B nurse cell nuclei there were a small number (7–15) of prominent HLBs, and in follicle cells there were also one or two HLBs present per cell (Fig. 8G,H). In the ARA mutant stage 10B nurse cell nuclei, there were a large number of much smaller foci in each nucleus (Fig. 8I,J,L). In contrast, the follicle cell nuclei at the same stage in the ARA mutant contained one HLB (Fig. 8K). Thus, there is mislocalization of SLBP in all stages and cell types in the egg chamber, while the HLBs are altered in stage 10B of oogenesis and normal in follicle cell nuclei.

The effect on localization of SLBP in stage 10B is quantified in Fig. 6G, and the effect on the number of HLBs in Fig. 8L. Note that the HLBs in the mutants are more numerous and smaller. Thus the large HLBs in the wild-type stage 10B nurse cells, which are ∼1000C and contain 100,000 total repeat units (500,000 total histone genes), contain about 10,000 repeat units (50,000 total genes), while in the mutant there are many more foci, each likely with a fewer number of repeat units and histone genes. In agreement with the number of HLBs in wild-type stage 10B egg chambers, Hammond and Laird reported there were ∼12 areas of concentration of histone genes in each cell nucleus as shown by DNA-FISH (Hammond and Laird, 1985a).

We conclude that the basic region of SLBP is responsible for the maternal effect lethal phenotype and that phosphorylation of the SFTPP region is not relevant to the deposition of maternal histone mRNA into the oocyte. The failure to concentrate SLBP in the nucleus of stage 10B nurse cells, results in failure to transcribe the histone genes, and the failure to form the large clusters of histone genes in stage 10B nuclei. Instead the HLBs are fragmented into multiple small HLBs. In earlier stages of oogenesis and in somatic follicle cells, the SLBP is still not concentrated in the nuclei, but this has only a minor effect on histone mRNA production. Thus the effect of these mutations on histone gene transcription is restricted to nurse cells in stage 10B and later nurse cells.

DISCUSSION

Histone mRNAs and proteins are expressed in large amounts only during S-phase. One time in the Drosophila life cycle that histone mRNAs are expressed at high levels in the absence of DNA replication is at the end of oogenesis, when the histone mRNAs deposited into the egg are synthesized (Ruddell and Jacobs-Lorena, 1985; Ambrosio and Schedl, 1985; Walker and Bownes, 1998). At this time, the demand for histone mRNA is high, since enough histone mRNA and histone protein must be deposited into the egg to provide enough histones for the first 14 cell cycles.

SLBP is a critical factor for histone mRNA biogenesis and function, since it is required for histone pre-mRNA processing, and is stoichiometrically bound to cytoplasmic histone mRNA, where it is required for translation (Marzluff and Koreski, 2017). Thus large amounts of SLBP are required not only for efficient processing but also for accumulation of large amounts of cytoplasmic histone mRNA (Sullivan et al., 2009). Processing of Drosophila pre-mRNA in vitro requires only the C-terminal 89 amino acids of SLBP; the RNA-binding domain and the C-terminal 17 amino acids (Dominski et al., 2005). While the requirements in SLBP for efficient histone pre-mRNA processing in vitro are well understood (Skrajna et al., 2017, 2016; Sabath et al., 2013; Dominski et al., 2005), whether there are additional requirements in SLBP for efficient processing in vivo is not known. Here, we report that a 10 aa region in the N-terminal domain of SLBP is required for deposition of maternal histone mRNA into the oocyte. In the SLBPΔ30, SLBPARA and SLBPAAA mutants, sufficiently processed histone mRNAs accumulate to support normal development. There is production of small amounts of polyadenylated histone mRNA in embryos, larvae and ovaries.

The most severe effect is on the deposition of histone mRNA into the oocyte. In the mutants, histone mRNAs are produced at normal levels during the nurse cell endoreduplication cycles, as well as in the follicle cells. In wild-type egg chambers, histone mRNAs deposited into the egg are synthesized starting in stage 10B. In contrast, very little transcription is detected at the histone locus in stage 10B in the mutants. This failure is correlated with the failure to concentrate large amounts of SLBP in the nuclei, either as a result of the production of smaller amounts of normal SLBP, or normal amounts of an SLBP which is defective in concentrating in the nucleus.

How are maternal stores of histone mRNA produced independently of DNA replication?

We confirmed the initial reports of 35 years ago (Ruddell and Jacobs-Lorena, 1985; Ambrosio and Schedl, 1985) that maternal histone mRNAs are synthesized only after the completion of nurse cell endoreduplication. Histone mRNAs are expressed only in nurse cells that are in S-phase, and are degraded at the end of each S-phase. Prior to stage 10B, histone mRNAs are not transported into the oocyte. Synthesis of histone mRNAs for deposition in the oocyte is initiated during stage 10B, and continues until the end of oogenesis. This is in contrast to mRNAs such as bicoid, gurken and oskar, which are localizing at specific regions within the developing oocyte prior to stage 10B and are critical for the development of the egg and embryo (Ephrussi et al., 1991; Kim-Ha et al., 1991; Neuman-Silberberg and Schüpbach, 1993; Berleth et al., 1988).

It is likely that accumulation of histone mRNA within the oocyte requires nurse cell dumping, an actin-driven process that begins at stage 10B (Buszczak and Cooley, 2000). During dumping, their cytoplasmic contents are transferred into the egg. Histone genes continue to be expressed at high levels in nurse cells even during late stages of egg chamber maturation (Fig. 5C). Thus, although some of the nurse cells are undergoing apoptosis (Buszczak and Cooley, 2000), the ones that remain continue to transcribe histone genes. Although germ plasm mRNAs such as oskar and nanos continue to accumulate at the posterior of the oocyte during late stage of egg chamber maturation, this localization relies on active localization pathways rather than continued transcription (Sinsimer et al., 2011; Snee et al., 2007).

SLBP is required for transcription of histone genes at stage 10B in oogenesis

The HLB serves to concentrate factors required for both transcription and pre-mRNA processing at the histone genes (Marzluff and Koreski, 2017). In Drosophila, histone gene transcription is activated after activation of cyclin E–Cdk2 (Lanzotti et al., 2004b) which phosphorylates the core HLB factor Mxc, which can be detected with the antibody mpm2 in S-phase cells (White et al., 2007, 2011). In stage 10B oocytes, all the nurse cell nuclei produce histone mRNA outside of S-phase in the absence of phosphorylation of Mxc detected by the mpm2 antibody.

One difference in stage 10B egg chambers in the maternal effect lethal mutants was a low concentration of SLBP in the nucleus, due to inefficient nuclear localization in the SLBPΔ30 and SLBPARA mutants and low levels of total SLBP in the SLBP10 mutant. Surprisingly, this lack of SLBP leads to low levels of histone gene transcription and disruption of normal HLB structure in the stage 10B egg chambers. Since the in situ experiments detect nascent transcripts at the HLBs, the defect is likely at the level of transcription although we cannot rule out that the transcripts are rapidly degraded while still bound at the histone genes.

In other cells (endoreduplicating nurse cells and ovarian follicle cells) normal amounts of properly processed histone mRNAs accumulate in these mutants, although there is also some misprocessed RNAs that are polyadenylated, likely due to low concentrations of SLBP in the nucleus resulting in inefficient processing.

It is possible that the structure and/or composition of the HLBs in wild-type nurse cells may change during oogenesis between nurse cells undergoing endoreduplication cycles and the cells in stage 10B, which makes it possible for them to express histone mRNAs. The failure of SLBP10, SLBPΔ30 and the SLBPARA mutants to deposit histone mRNAs in the egg is correlated with the low concentration of the SLBP in the nucleus. Normally, mammalian cells have a pool of SLBP which is concentrated in the nucleus (Erkmann et al., 2005). Drosophila SLBP shows this same pattern of localization (Fig. 6A,D). In the SLBP10 mutant, SLBP is concentrated in the nucleus, but there is a lower concentration of SLBP in the nucleus, as a result of the overall lower amount of the protein (Fig. 6B,E). In contrast to mammalian SLBP, which has several potential nuclear localization signals (Erkmann et al., 2005), there is only a single predicted canonical nuclear localization sequence in Drosophila SLBP, which is deleted in SLBPΔ30 and mutated in SLBPARA. One possibility is that this signal is particularly important in the stage 10B nurse cells, either for efficient transport into or nuclear retention of SLBP, and the low concentration of SLBP in the nucleus prevents SLBP from functioning in activating histone gene transcription. It is also possible that the region deleted may be directly involved in the transcription of histone genes, possibly by interacting with factors in the HLB, or that the low concentrations of SLBP in the nucleus may indirectly prevent histone gene activation.

These results suggest that SLBP may be required for histone gene transcription from the HLB when there is no phosphorylation of Mxc. How SLBP might participate in transcription is not clear. It is possible that SLBP interacts with an HLB component to activate gene transcription, and this interaction requires high concentrations of SLBP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks

w[1118] was used as the wild-type stock [Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) #5905]. The shRNA strains were: eb1 shRNA used as a control (BDSC #36680, donor TRiP) and slbp shRNA (BDSC #56876, donor TRiP). shRNA expression was driven using P(w[+mC]=matalpha4-GAL-VP16)V37 (BDSC #7063, donor Andrea Brand).

CRISPR mutagenesis of Drosophila SLBP

To obtain mutants of SLBP, we designed a guide RNA directed against a sequence in the second exon of SLBP with the PAM site at amino acid 112 that targets the template strand (Clarke et al., 2018), using the FLY CRISPR strategy (Gratz et al., 2013, 2015). 5′ phosphorylated oligonucleotides to express the guide RNA were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. The oligonucleotides were annealed, and ligated into the BbsI sites of pU6-BbSI-chiRNA (Sense, 5′Phos-CTTCGAACGAGTGTCGGCGCTTGT-3′; antisense, 5′Phos-AAACACAAGCGCCGACACTCGTTC-3′).

The guide RNAs were injected into BDSC #54591 Drosophila embryos, which express Cas9, by BestGene Inc. The flies were screened by PCR of a 300 nt region around the PAM site, and the PCR products sequenced to detect CRISPR events. The PCR fragments were then cloned and sequenced to confirm the sequence change that occurred.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for immunofluorescence: rabbit anti-FLASH (1:10,000) (Burch et al., 2011); mouse mpm2 (Sigma-Aldrich; cat. no. 05-368, 1:10,000); rabbit anti-SLBP (Skrajna et al., 2017) (1:200); goat anti-rabbit-IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 and 488 (Life Technologies, 1:400 and 1:200, respectively); goat anti-mouse-IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 and 488 (Life Technologies, 1:400 and 1:200, respectively).

RNA and protein analysis

Histone mRNAs were analyzed by northern blotting using probes to the coding region of either dH3 or dH1. As a loading control, a probe to the coding region of 7SK RNA was used; 5 μg of total RNA was resolved on a 6% acrylamide-7 M gel at 500 V with 1× Tris, borate and EDTA buffer (TBE). The samples contained xylene cyanol dye. After the dye had run off the gel (∼1.1 h), the gel was run for another 30 min. The RNA was transferred to a positively charged nylon transfer membrane (GE Healthcare) by electroblotting. The membrane was crosslinked with UV crosslinked in a Stratalinker (3× at 12,000 units) and then hybridized with probes to histone mRNA. The RNA was detected by autoradiography or with a Phosphorimager. The filter was then stripped and hybridized to a probe for 7SK RNA. In some experiments the two probes were mixed prior to hybridization.

Proteins were resolved on an 8% polyacrylamide-SDS gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, incubated with the antibody to SLBP and the SLBP detected using ECL reagent. The membrane was then incubated with the β-actin antibody (GeneTex; cat. no. 41554, 1:10,000) as a loading control.

Ovaries were processed for in situ hybridization using a published protocol (Goldman et al., 2019). Dissected ovaries were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 20 min. Next, the ovaries were washed with PBST (PBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100) and teased apart using a pipette. The ovaries were washed with 100% methanol for 5 min, then stored for 1 h in 100% methanol at −20°C. The samples were then gradually re-hydrated into PBST. The samples were then washed for 10 min in wash buffer (4× SSC, 35% deionized formamide and 0.1% Tween 20). Probes were diluted in hybridization buffer [10% dextran sulfate, 0.1 mg/ml salmon sperm (ss)DNA, 100 µl vanadyl ribonucleoside (NEB Biolabs), 20 μg/ml RNase-free BSA, 4× SSC, 0.1% Tween 20 and 35% deionized formamide] and were incubated with the sample overnight at 37°C. The following day, the samples were washed twice with wash buffer for 30 min. After two rinses with PBST and staining with DAPI, the ovaries were mounted on slides using Prolong Diamond (Life Technologies) and imaged. The probes used were obtained from Stellaris and have been described previously (Hur et al., 2020).

Immunofluorescence

Ovaries were processed for immunofluorescence using a previously described procedure (Goldman et al., 2019). Briefly, flies were fattened on yeast pellets for 3 days. Ovaries were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (Pierce) for 20 min. Primary antibody was incubated with ovaries in 1× PBST plus 0.2% BSA (Promega) overnight at 4°C. The samples were then washed three times in PBST. The secondary antibody diluted in 1× PBST plus 0.2% BSA was incubated with the sample overnight at 4°C. Following washes in PBST, the samples were mounted onto slides with Prolong Diamond (Life Technologies). For combined in situ and immunofluorescence, the ovaries were first processed for immunofluorescence. After removal of the secondary antibody, the samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 5 min. Next, the samples were placed in 100% methanol for 1 h at −20°C. After this incubation, the samples were processed for in situ hybridization as described in the above section.

The nuclear enrichment of SLBP was quantified using the Zen software from Zeiss. The mean signal intensity in a Stage 10B nurse cell nucleus was divided by the mean intensity of a comparable area in the cytoplasm of the same egg chamber. The size and number of the HLB was quantified using the Fiji/ImageJ software. The particle analysis tool was used. For both analyses, a total of ten egg chambers were quantified for each genotype.

Microscopy

Images were captured on a Zeiss LSM 780 inverted microscope equipped with Airyscan (Augusta University Cell Imaging Core). Images were processed for presentation using Adobe Photoshop, and Adobe Illustrator.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Stefano Di Talia (Duke Univ.) and Bob Duronio and Jim Kemp (UNC) for the in situ probes, and Xiao Yang for affinity purification of the SLBP antibody.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: G.B.G., W.F.M.; Methodology: J.M.P.-B., G.B.G.; Validation: J.M.P.-B.; Formal analysis: G.B.G.; Investigation: J.M.P.-B., G.B.G.; Resources: W.F.M.; Writing - original draft: J.M.P.-B., W.F.M.; Writing - review & editing: J.M.P.-B., G.B.G., W.F.M.; Supervision: W.F.M.; Project administration: W.F.M.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01GM58921 (W.F.M.), GM29832-41S1 (W.F.M. and J.M.P.-B). and R01GM100088 to G.B.G. J.M.P.-B. also received support from NIH grant R25GM055336. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at https://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.251728.supplemental

Peer review history

The peer review history is available online at https://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.251728.reviewer-comments.pdf

References

- Ambrosio, L. and Schedl, P. (1985). Two discrete modes of histone gene expression during oogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Biol. 111, 220-231. 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90447-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, J. R., Lee, A. M. and Wu, C.-T. (2006). Site-specific transformation of Drosophila via φC31 integrase-mediated cassette exchange. Genetics 173, 769-777. 10.1534/genetics.106.056945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berleth, T., Burri, M., Thoma, G., Bopp, D., Richstein, S., Frigerio, G., Noll, M. and Nüsslein-Volhard, C. (1988). The role of localization of bicoid RNA in organizing the anterior pattern of the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 7, 1749-1756. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03004.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongartz, P. and Schloissnig, S. (2019). Deep repeat resolution-the assembly of the Drosophila Histone Complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, e18 10.1093/nar/gky1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers, C. H., Thapar, R., Petrotchenko, E. V., Torres, M. P., Speir, J. P., Easterling, M., Dominski, Z. and Marzluff, W. F. (2006). Combined top-down and bottom-up proteomics identifies a phosphorylation site in stem-loop-binding proteins that contributes to high-affinity RNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 3094-3099. 10.1073/pnas.0511289103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch, B. D., Godfrey, A. C., Gasdaska, P. Y., Salzler, H. R., Duronio, R. J., Marzluff, W. F. and Dominski, Z. (2011). Interaction between FLASH and Lsm11 is essential for histone pre-mRNA processing in vivo in Drosophila. RNA 17, 1132-1147. 10.1261/rna.2566811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszczak, M. and Cooley, L. (2000). Eggs to die for: cell death during Drosophila oogenesis. Cell Death Differ. 7, 1071-1074. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, R., Heler, R., MacDougall, M. S., Yeo, N. C., Chavez, A., Regan, M., Hanakahi, L., Church, G. M., Marraffini, L. A. and Merrill, B. J. (2018). Enhanced bacterial immunity and mammalian genome editing via RNA-polymerase-mediated dislodging of Cas9 from double-strand DNA breaks. Mol. Cell 71, 42-55.e8. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominski, Z., Yang, X., Raska, C. S., Santiago, C. S., Borchers, C. H., Duronio, R. J. and Marzluff, W. F. (2002). 3′ end processing of Drosophila melanogaster histone pre-mRNAs: requirement for phosphorylated Drosophila stem-loop binding protein and coevolution of the histone pre-mRNA processing system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6648-6660. 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6648-6660.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominski, Z., Yang, X., Purdy, M. and Marzluff, W. F. (2005). Differences and similarities between Drosophila and mammalian 3′ end processing of histone pre-mRNAs. RNA 11, 1835-1847. 10.1261/rna.2179305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duronio, R. J. and Marzluff, W. F. (2017). Coordinating cell cycle-regulated histone gene expression through assembly and function of the Histone Locus Body. RNA. Biol. 14, 726-738. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1265198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ephrussi, A., Dickinson, L. K. and Lehmann, R. (1991). Oskar organizes the germ plasm and directs localization of the posterior determinant nanos. Cell 66, 37-50. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90137-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkmann, J. A., Wagner, E. J., Dong, J., Zhang, Y. P., Kutay, U. and Marzluff, W. F. (2005). Nuclear import of the stem-loop binding protein and localization during the cell cycle. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 2960-2971. 10.1091/mbc.e04-11-1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley, K. and Cooley, L. (1998). Apoptosis in late stage Drosophila nurse cells does not require genes within the H99 deficiency. Development 125, 1075-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, A. C., Kupsco, J. M., Burch, B. D., Zimmerman, R. M., Dominski, Z., Marzluff, W. F. and Duronio, R. J. (2006). U7 snRNA mutations in Drosophila block histone pre-mRNA processing and block oogenesis. RNA 12, 396-409. 10.1261/rna.2270406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, A. C., White, A. E., Tatomer, D. C., Marzluff, W. F. and Duronio, R. J. (2009). The Drosophila U7 snRNP proteins Lsm10 and Lsm11 are required for histone pre-mRNA processing and play an essential role in development. RNA 15, 1661-1672. 10.1261/rna.1518009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, C. H., Neiswender, H., Veeranan-Karmegam, R. and Gonsalvez, G. B. (2019). The Egalitarian binding partners Dynein light chain and Bicaudal-D act sequentially to link mRNA to the Dynein motor. Development 146, dev176529 10.1242/dev.176529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, S. J., Cummings, A. M., Nguyen, J. N., Hamm, D. C., Donohue, L. K., Harrison, M. M., Wildonger, J. and O'Connor-Giles, K. M. (2013). Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics 194, 1029-1035. 10.1534/genetics.113.152710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, S. J., Harrison, M. M., Wildonger, J. and O'Connor-Giles, K. M. (2015). Precise genome editing of Drosophila with CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9. Methods Mol. Biol. 1311, 335-348. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2687-9_22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth, A. C., Fish, M., Nusse, R. and Calos, M. P. (2004). Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage phiC31. Genetics 166, 1775-1782. 10.1534/genetics.166.4.1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günesdogan, U., Jäckle, H. and Herzig, A. (2010). A genetic system to assess in vivo the functions of histones and histone modifications in higher eukaryotes. EMBO Rep. 11, 772-776. 10.1038/embor.2010.124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, M. P. and Laird, C. D. (1985a). Chromosome structure and DNA replication in nurse and follicle cells of Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma 91, 267-278. 10.1007/BF00328222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur, W., Kemp, J. P., Jr, Tarzia, M., Deneke, V. E., Marzluff, W. F., Duronio, R. J. and Di Talia, S. (2020). CDK-regulated phase separation seeded by histone genes ensures precise growth and function of histone locus bodies. Dev. Cell 54, 379-394.e6. 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iampietro, C., Bergalet, J., Wang, X., Cody, N. A., Chin, A., Lefebvre, F. A., Douziech, M., Krause, H. M. and Lecuyer, E. (2014). Developmentally regulated elimination of damaged nuclei involves a Chk2-dependent mechanism of mRNA nuclear retention. Dev. Cell29, 468-481. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim-Ha, J., Smith, J. L. and MacDonald, P. M. (1991). oskar mRNA is localized to the posterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Cell 66, 23-35. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90136-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, Y., Rothman, J. H., Sugimoto, A. and Yamamoto, M. (2002). The stem-loop binding protein CDL-1 is required for chromosome condensation, progression of cell death and morphogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 129, 187-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi, S., Hasebe, M., Tomita, M. and Yanagawa, H. (2009). Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA106, 10171-10176. 10.1073/pnas.0900604106 [DOI]

- Lafave, M. C. and Sekelsky, J. (2011). Transcription initiation from within P elements generates hypomorphic mutations in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 188, 749-752. 10.1534/genetics.111.129825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzotti, D. J., Kaygun, H., Yang, X., Duronio, R. J. and Marzluff, W. F. (2002). Developmental control of histone mRNA and dSLBP synthesis during Drosophila embryogenesis and the role of dSLBP in histone mRNA 3′ processing in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 2267-2282. 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2267-2282.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzotti, D. J., Kupsco, J. M., Yang, X.-C., Dominski, Z., Marzluff, W. F. and Duronio, R. J. (2004a). Drosophila stem-loop binding protein intracellular localization is mediated by phosphorylation and is required for cell cycle-regulated histone mRNA expression. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15, 1112-1123. 10.1091/mbc.e03-09-0649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzotti, D. J., Kupsco, J. M., Marzluff, W. F. and Duronio, R. J. (2004b). Stringcdc25 and cyclin E are required for patterned histone expression at different stages of Drosophila embryonic development. Dev. Biol. 274, 82-93. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifton, R. P., Goldberg, M. L., Karp, R. W. and Hogness, D. S. (1978). The organization of the histone genes in drosophila melanogaster: functional and evolutionary implications. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol, 42, 1047-1051. 10.1101/SQB.1978.042.01.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzluff, W. F. and Koreski, K. P. (2017). Birth and Death of Histone mRNAs. Trends Genet. 33, 745-759. 10.1016/j.tig.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzluff, W. F., Wagner, E. J. and Duronio, R. J. (2008). Metabolism and regulation of canonical histone mRNAs: life without a poly(A) tail. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 843-854. 10.1038/nrg2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckay, D. J., Klusza, S., Penke, T. J. R., Meers, M. P., Curry, K. P., Mcdaniel, S. L., Malek, P. Y., Cooper, S. W., Tatomer, D. C., Lieb, J. D.et al. (2015). Interrogating the function of metazoan histones using engineered gene clusters. Dev. Cell 32, 373-386. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman-Silberberg, F. S. and Schüpbach, T. (1993). The Drosophila dorsoventral patterning gene gurken produces a dorsally localized RNA and encodes a TGFα-like protein. Cell 75, 165-174. 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80093-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt, J., Crombie, C., Schümperli, D. and Müller, B. (2002). The Caenorhabditis elegans histone hairpin-binding protein is required for core histone expression and is essential for embryonic and postembryonic cell division. J. Cell Sci. 115, 857-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett, T. L., Tanner, E. A. and Mccall, K. (2009). Cracking open cell death in the Drosophila ovary. Apoptosis 14, 969-979. 10.1007/s10495-009-0369-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddell, A. and Jacobs-Lorena, M. (1985). Biphasic pattern of histone gene expression during Drosophila oogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 3316-3319. 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabath, I., Skrajna, A., Yang, X.-C., Dadlez, M., Marzluff, W. F. and Dominski, Z. (2013). 3′ end processing of histone pre-mRNAs in Drosophila: U7 snRNP is associated with FLASH and polyadenylation factors. RNA 19, 1726-1744. 10.1261/rna.040360.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sànchez, R. and Marzluff, W. F. (2002). The stem-loop binding protein is required for efficient translation of histone mRNA in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7093-7104. 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7093-7104.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinsimer, K. S., Jain, R. A., Chatterjee, S. and Gavis, E. R. (2011). A late phase of germ plasm accumulation during Drosophila oogenesis requires lost and rumpelstiltskin. Development 138, 3431-3440. 10.1242/dev.065029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrajna, A., Yang, X.-C., Tarnowski, K., Fituch, K., Marzluff, W. F., Dominski, Z. and Dadlez, M. (2016). Mapping the interaction network of key proteins involved in histone mRNA generation - a hydrogen/deuterium exchange study. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 1180-1196. 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrajna, A., Yang, X.-C., Bucholc, K., Zhang, J., Hall, T. M. T., Dadlez, M., Marzluff, W. F. and Dominski, Z. (2017). U7 snRNP is recruited to histone pre-mRNA in a FLASH-dependent manner by two separate regions of the Stem-Loop Binding Protein. RNA 23, 938-951. 10.1261/rna.060806.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snee, M. J., Harrison, D., Yan, N. and Macdonald, P. M. (2007). A late phase of Oskar accumulation is crucial for posterior patterning of the Drosophila embryo, and is blocked by ectopic expression of Bruno. Differentiation 75, 246-255. 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00136.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, E., Santiago, C., Parker, E. D., Dominski, Z., Yang, X., Lanzotti, D. J., Ingledue, T. C., Marzluff, W. F. and Duronio, R. J. (2001). Drosophila stem loop binding protein coordinates accumulation of mature histone mRNA with cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 15, 173-187. 10.1101/gad.862801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, K. D., Mullen, T. E., Marzluff, W. F. and Wagner, E. J. (2009). Knockdown of SLBP results in nuclear retention of histone mRNA. RNA. 15, 459-472. 10.1261/rna.1205409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatomer, D. C., Terzo, E., Curry, K. P., Salzler, H., Sabath, I., Zapotoczny, G., Mckay, D. J., Dominski, Z., Marzluff, W. F. and Duronio, R. J. (2016). Concentrating pre-mRNA processing factors in the histone locus body facilitates efficient histone mRNA biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 213, 557-570. 10.1083/jcb.201504043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, E. J., Burch, B. D., Godfrey, A. C., Salzler, H. R., Duronio, R. J. and Marzluff, W. F. (2007). A genome-wide RNA interference screen reveals that variant histones are necessary for replication-dependent histone pre-mRNA processing. Mol. Cell 28, 692-699. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J. and Bownes, M. (1998). The expression of histone genes during Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis. Dev. Genes Evol. 207, 535-541. 10.1007/s004270050144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, A. E., Leslie, M. E., Calvi, B. R., Marzluff, W. F. and Duronio, R. J. (2007). Developmental and cell cycle regulation of the Drosophila histone locus body. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 2491-2502. 10.1091/mbc.e06-11-1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, A. E., Burch, B. D., Yang, X.-C., Gasdaska, P. Y., Dominski, Z., Marzluff, W. F. and Duronio, R. J. (2011). Drosophila histone locus bodies form by hierarchical recruitment of components. J. Cell Biol. 193, 677-694. 10.1083/jcb.201012077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield, M. L., Kaygun, H., Erkmann, J. A., Townley-Tilson, W. H. D., Dominski, Z. and Marzluff, W. F. (2004). SLBP is associated with histone mRNA on polyribosomes as a component of the histone mRNP. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 4833-4842. 10.1093/nar/gkh798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.-C., Burch, B. D., Yan, Y., Marzluff, W. F. and Dominski, Z. (2009). FLASH, a proapoptotic protein involved in activation of caspase-8, is essential for 3′ end processing of histone pre-mRNAs. Mol. Cell 36, 267-278. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.-C., Xu, B., Sabath, I., Kunduru, L., Burch, B. D., Marzluff, W. F. and Dominski, Z. (2011). FLASH is required for the endonucleolytic cleavage of histone pre-mRNAs but is dispensable for the 5′ exonucleolytic degradation of the downstream cleavage product. Mol. Cell Biol. 31, 1492-1502. 10.1128/MCB.00979-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.-X., Dominski, Z., Yang, X.-C., Elms, P., Raska, C. S., Borchers, C. H. and Marzluff, W. F. (2003). Phosphorylation of Stem-Loop Binding Protein (SLBP) on two threonines triggers degradation of SLBP, the sole cell cycle-regulated factor required for regulation of histone mRNA processing, at the end of S phase. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 1590-1601. 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1590-1601.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.