Abstract

We developed a clinical probe capable of acquiring simultaneous short wavelength infrared (SWIR) reflectance and occlusal transillumination images of lesions on tooth proximal and occlusal surfaces to reduce the potential of false positives. The dual probe is 3D-printed and the imaging system uses a Ge-enhanced camera and fiber-optic light sources that use SWIR light at 1300-nm for occlusal transillumination and SWIR 1450-nm light for reflectance measurements. The purpose of this study was to test the performance of the probe on extracted teeth prior to commencing clinical studies. The dual probe was used to image extracted teeth with proximal and occlusal lesions. SWIR images of each tooth were compared with micro-CT images to assess performance.

Keywords: near-IR imaging, caries detection, reflectance, transillumination

1. INTRODUCTION

Short wavelength infrared (SWIR) and near-IR imaging methods have been under development for almost 20 years for the use in dentistry and several clinical devices are now available commercially. Due to the high transparency of enamel in the near-IR, novel imaging configurations are feasible in which the tooth can be imaged from the occlusal surface after shining light at and below the gum line, which we call occlusal transillumination [1, 2]. Approximal lesions can be imaged by occlusal transillumination of the proximal contact points between teeth and by directing near-IR light below the crown while imaging the occlusal surface [2–4]. The latter approach is capable of imaging occlusal lesions as well with high contrast [1, 2, 5–8]. In 2010, it was demonstrated that approximal lesions that appeared on radiographs could be detected in vivo with near-IR imaging with similar sensitivity [2] and that occlusal transillumination could be employed clinically. This was the first step in demonstrating the clinical potential of near-IR imaging for approximal caries detection. In the most recent clinical study [9] at wavelengths greater than 1300-nm, the diagnostic performance of both near-IR transillumination and near-IR reflectance probes were used to screen premolar teeth scheduled for extraction for caries lesions. The teeth were collected, sectioned and examined with polarized light microscopy and transverse microradiography which served as the gold standard. In addition, extra-oral radiographs were taken of teeth and the diagnostic performance of near-IR imaging was compared with radiography. Near-IR imaging was shown to be significantly more sensitive than radiography for the detection of lesions on both occlusal and proximal tooth surfaces in vivo. The sensitivity of the combined near-IR imaging probes was significantly higher (P<0.05) than radiographs for both occlusal and proximal lesions in vivo. It was anticipated that near-IR methods would be more sensitive than radiographs since the radiographic sensitivity for occlusal lesions is extremely poor, however, the sensitivity was also much higher for approximal lesions than radiography, 0.53 vs 0.23. In addition, the sensitivity of each individual near-IR method was found to be either individually equal to or higher than radiography.

The most recent epidemiological data gathered from the National Health and Nutritional Survey (NHANES) [10, 11] and Dental Practice-Based Research Network (DPBRN) [12–14] indicates that nearly one third of all patients have a questionable occlusal carious lesion (QOC) located on a posterior tooth. QOC’s are given the name “questionable” because clinicians’ lack instrumentation capable of measuring the depth of pit and fissure lesions to determine if the dental decay has reached the underlying dentin. Digital x-rays are not sensitive enough to detect occlusal lesions, and visible diagnosis is confounded by stain trapped in the occlusal anatomy [15]. Prior in vitro studies attempted to use combined SWIR reflectance and transillumination measurements to estimate QOC depth [7, 16, 17]. Multispectral SWIR reflectance measurements have demonstrated that the tooth appears darker at wavelengths coincident with increased water absorption. Moreover, multispectral images can be used to produce increased contrast between different tooth structures such as sound enamel and dentin, dental decay and composite restorative materials [18–20]. Combining measurements from different SWIR imaging wavelengths and comparing them with concurrent measurements acquired by complementary imaging modalities should provide improved assessment of lesion depth and severity.

We hypothesize that a combined SWIR reflectance and transillumination probe will reduce false positives since it is unlikely that confounding structural features or specular reflection are going to be present in both reflectance and transillumination images. In addition, the dual probe will provide complementary diagnostic information about lesion severity to help discriminate early superficial lesions on tooth surfaces from deeply penetrating lesions.

Both the reflectance and the occlusal transillumination probes sample light that is emitted from tooth occlusal surfaces, therefore it is feasible to combine both methods into a single probe that can be positioned above the tooth that is practical for rapid clinical screening. Different illumination wavelengths that are optimized for each imaging mode can be used, namely 1450-nm for reflectance and 1300-nm for transillumination. This paper describes the design and performance of the dual SWIR transillumination/reflectance probe on extracted teeth with lesions on the proximal and occlusal surfaces. MicroCT was used as a gold standard for comparison.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sample Preparation

Extracted teeth were selected with occlusal and approximal lesions were selected for participation in this study. Teeth were collected from patients in the San Francisco Bay area with approval from the UCSF Committee on Human Research. The teeth were sterilized using gamma radiation and stored in 0.1% thymol solution to maintain tissue hydration and prevent bacterial growth.

The teeth were imaged using Microcomputed X-ray tomography (μCT) with a 10-μm resolution. A Scanco μCT 50 from Scanco USA (Wayne, PA) located at the UCSF Bone Imaging Core Facility was used to acquire the images.

2.2. Design of the dual SWIR probe

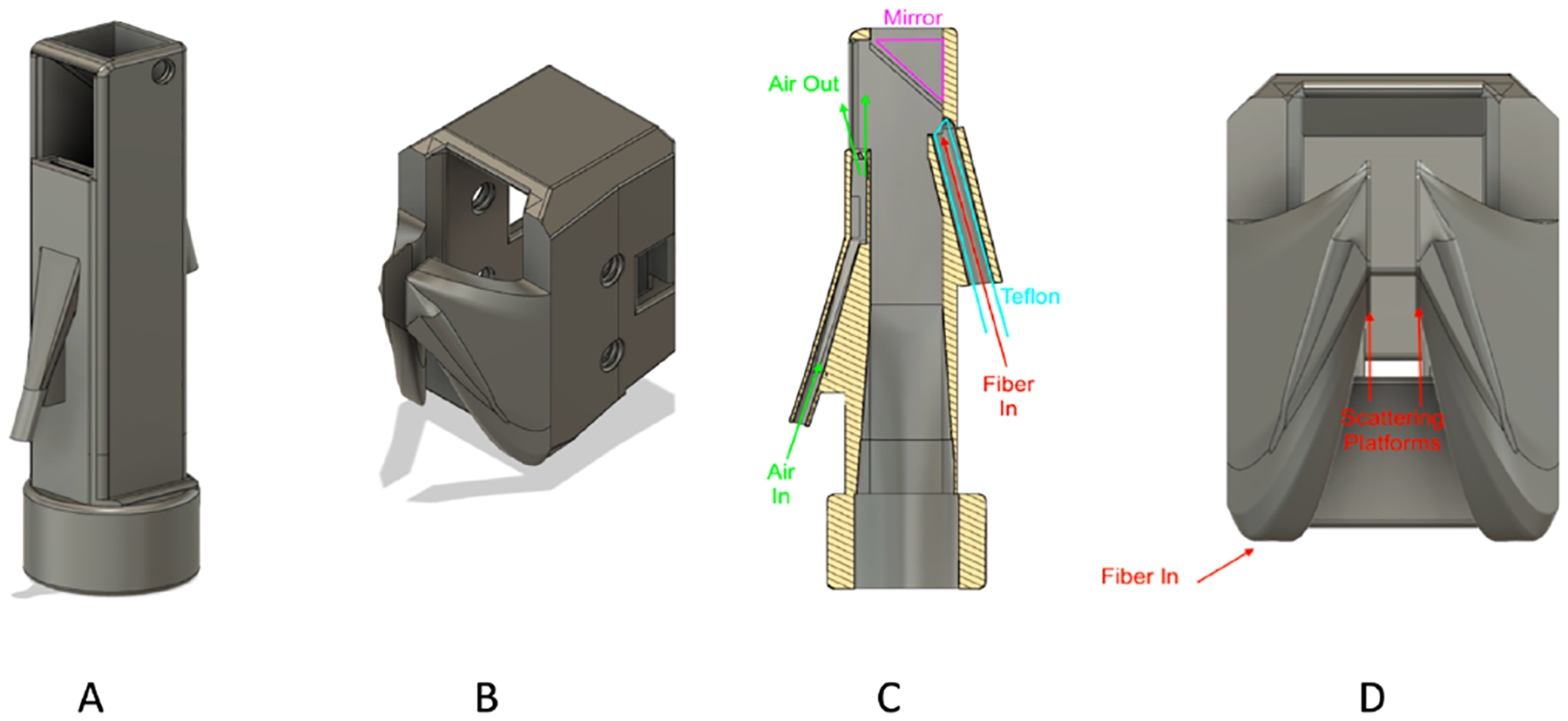

The dual probe was designed in Fusion 360 from Autodesk (San Francisco, CA). The dual probe design consists of a reflectance probe body and a transillumination attachment, shown in Figs. 1A and 1B.

Fig 1.

Designs of the transillumination/reflectance SWIR probe. (A) Reflectance probe body, (B) transillumination attachment, (C) reflectance probe body cross-sectional view; reflectance fiber is inserted from the back of the probe and enters a Teflon plug where light is scattered to the sample. (D) Front view of the transillumination attachment. Fibers are inserted from the bottom of the attachment and reach the scattering platform.

The reflectance probe body utilizes black resin to reduce artifacts from unwanted scattering in the probe assembly. A cross-sectional view of the reflectance probe body is shown in Fig. 1C. The reflectance fiber comes in from the back of the probe, entering a Teflon plug where the light is diffusely scattered to the sample. The bottom of the reflectance probe is designed to be attached to the camera, and light from the tooth is reflected off an aluminum mirror fitted to a 45-degree angle attached to the top of the probe. There is an air nozzle near the mirror to prevent fogging of the mirror. The air nozzle can also be used to dry the lesion to increase lesion contrast and potentially assess lesion activity [21–23].

The transillumination attachment is designed to be fabricated using Formlabs (Boston, MA) Flexible Resin. The flexible resin can tolerate moderate stretch and compression, making it an ideal choice for imaging teeth of different shapes and sizes. The transillumination attachment is designed to attach on top of the reflectance probe body.

Transillumination fibers enter from the bottom of the attachment and reach to the flexible scattering platforms. The scattering platforms are separated by only 2.8 mm, but they can easily stretch to reach up to 17 mm without breaking. Figure 1D shows the front view of the transillumination attachment design.

2.3. Fabrication of the dual SWIR probe

The reflectance probe body was fabricated using a Formlabs Form 3 Low Force Stereolithography 3D printer. The final design is exported as a STL file. The STL file is then transferred to Formlabs PreForm to generate supports for a final 3D printing scheme, shown in Fig. 2A. The scheme is then sent to the Form 3 printer for printing. The printing process for one reflectance probe takes about 5 hours and 15 minutes, with 832 layers at a resolution of 100-μm. The resin used for the reflectance probe is Formlabs Black Resin V4. After 3D printing, the uncured probe is then transferred to Formlabs Form Wash to rinse off the resin residue with isopropyl alcohol for 10 minutes. Finally, the probe is transferred to Formlabs Form Cure to cure at 60 degree-Celsius for 60 minutes. The Teflon plug is fabricated from 1/8” diameter Teflon rod. The Teflon plug is cut to a length of 35 mm with a razor blade. One end of the Teflon plug is trimmed to an angle of roughly 37 degrees. The center of the rod is then drilled with a 1.5-mm diameter drill to a distance of 33-mm and the optical fiber is inserted into the hollowed end of the plug. Fig. 2B shows a fabricated reflectance probe body.

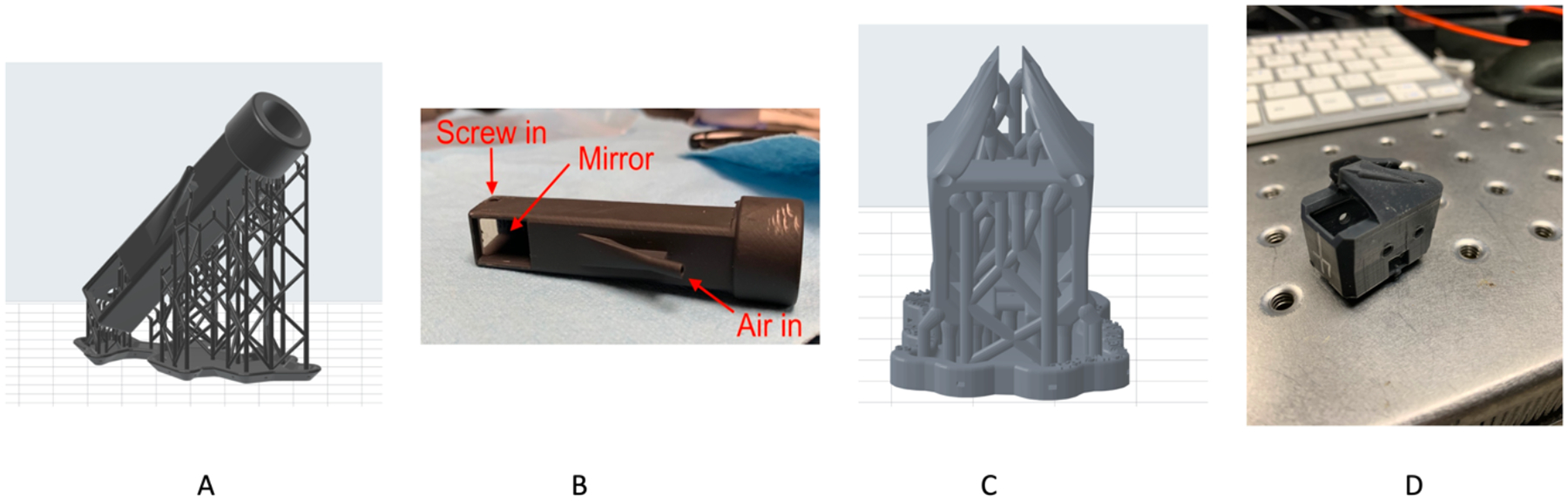

Fig 2.

Fabrication of the SWIR Dual Probe. (A) 3D-Printing scheme of the reflectance probe with support. (B) Fabricated reflectance probe body. (C) 3D-Printing scheme of the transillumination attachment with support. (D) Fabricated transillumination attachment.

The transillumination attachment was fabricated using a Formlabs Form 2 printer. Like the reflectance probe, the finished design is exported to Formlabs PreForm to generate supports for 3D printing, shown in Fig. 2C. Figure 2D shows a fabricated transillumination attachment.

2.4. Image Acquisition and Analysis

Twenty extracted teeth were imaged using the dual probe. Nine of them contained occlusal lesions and 11 of them contained approximal lesions. A NoblePeak Vision Triwave Imager, Model EC701 (Wakefield, MA) was used that employs a Germanium enhanced complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) focal plane array sensitive from 400–1600-nm with a larger array (640×480) and smaller pixel pitch (10-μm pixels) for higher resolution. Two lenses (f=50 and f=125) along with an adjustable aperture were placed between the handpiece and the Triwave imager to provide a field of view of 9 × 12 mm at the probe surface which is positioned at the surface of the tooth. A SLS201L Stabilized Tungsten-Halogen lamp from Thorlabs (Newton, NJ) with a 1450-nm longpass filter and a 1 mm in diameter low-OH optical fiber was used as the light source for reflectance. The two transillumination light sources are controlled via the Model 8008 Modular Controller (Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA), with one channel connected to a Model SLD72 1312-nm SLED from Covega Coporation (Jessup, MD) with 50-nm bandwidth, and the other channel connected to a Model DL-CS3452A SLED from POET Technologies (San Jose, CA). The light is delivered through two 0.4 mm in diameter low-OH optical fibers. The camera is cooled to −80 °C by a thermal electric cooler. The gain is set at 2 and the aperture is set at 5.5. The samples were dried with an air nozzle before imaging, due to the strong water absorption at 1450-nm [24]. The light sources were turned on and off manually and images were taken for each light source. The images were then analyzed using a program written with MATLAB from Mathworks (Natick, AM). The images are first converted to 16-bit normalized grayscale images. We utilized preexisting MATLAB code to generate contours of both sound and lesion ROIs [26]. It shows the average intensity and the intensity’s standard deviation within the contours. The contrast was calculated with (IL − IS)/IL for reflectance images and (IS – IL)/IS for transillumination images [25]. The lesion and sound ROIs are defined by manual segmentations. IL is the average intensity of the lesion ROI and IS is the average intensity of the sound ROI. The calculated SWIR contrast was compared with the μCT images. Figure 3 shows the experiment setup with the Dual SWIR probe.

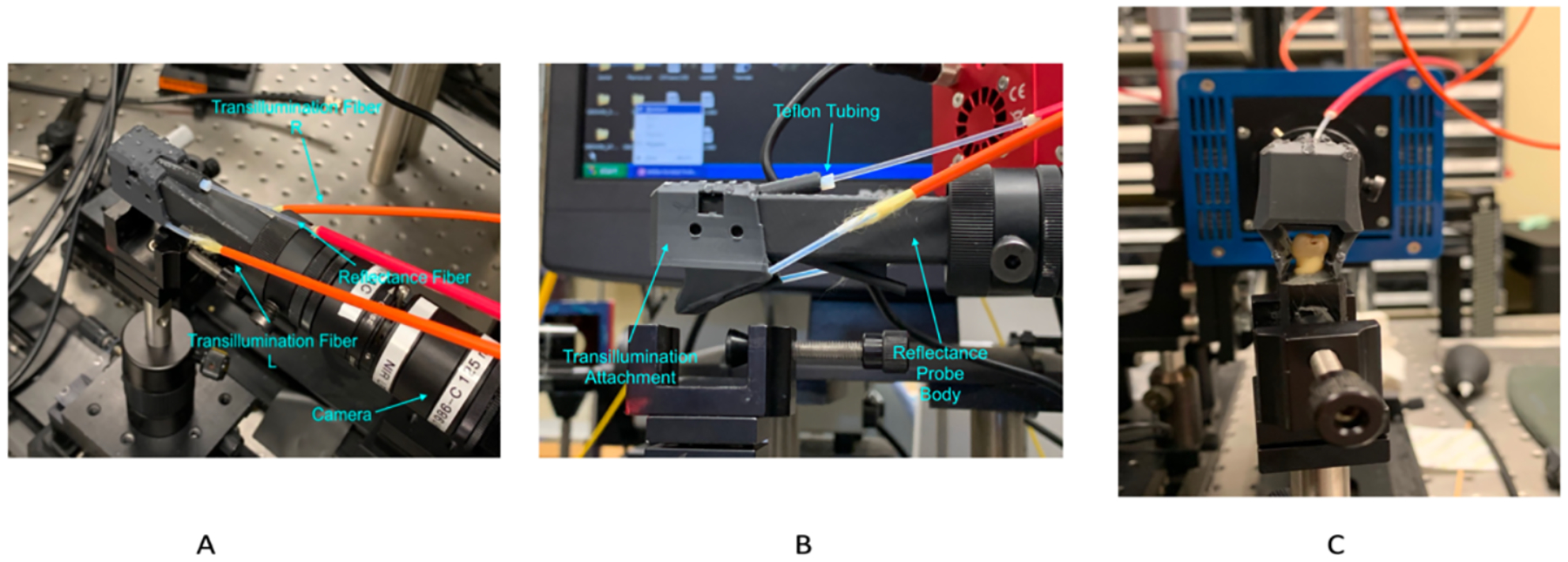

Fig 3.

Experiment setup. The Dual Probe is attached to the camera. (A) Top view of the imaging system. (B) Side view of the imaging system. (C) The dual probe is imaging an extracted tooth. The tooth is located between the transillumination scattering platforms.

2.5. Correction of Artifacts at 1300 nm

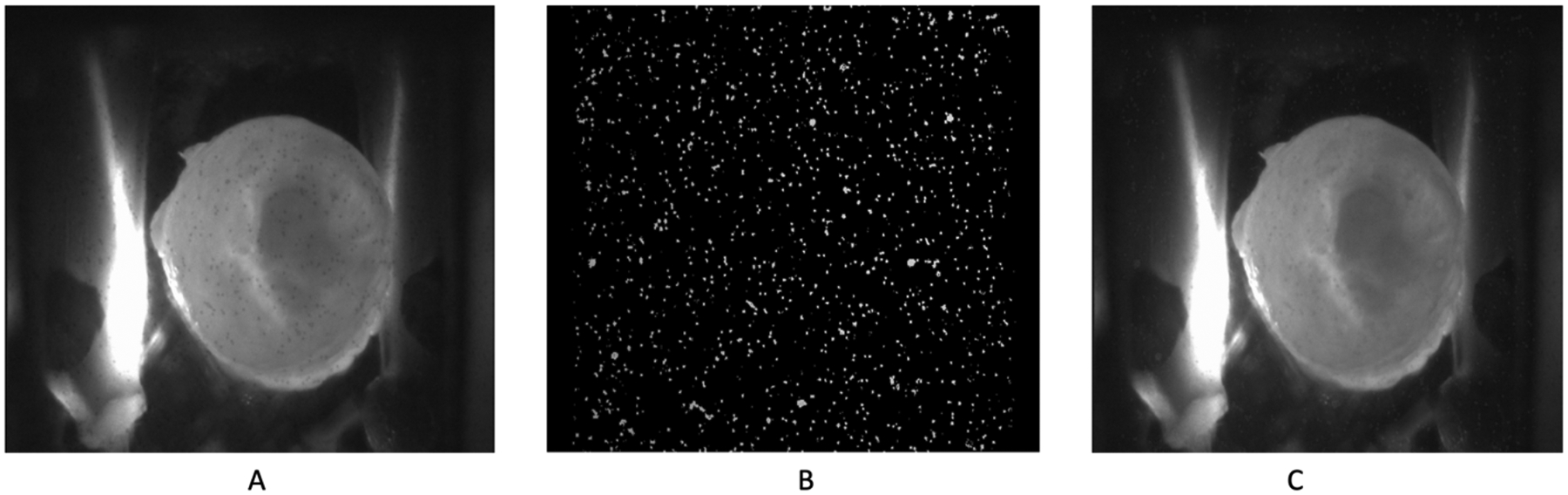

The response of the TriWave camera near 1300 nm is not uniform as shown in Fig. 4. Therefore, we used an algorithm to correct the artifacts by adding intensity compensation at the artifact locations. Acquired images were analyzed through MATLAB’s image segmenter. The program generates a mask of the artifacts, as shown in Fig. 4 B. The mask is then exported to an uncorrected image of the tooth. Within the new masked image, an inverse of the image intensity was taken on the mask and applied to the masked locations of the uncorrected image. The compensation can be adjusted by multiplying different correction factors of the inverse of intensity at the masked locations. The correction factor was set to 0.07 in this study. Figure 4C shows a corrected transillumination image.

Fig 4.

(A) A sample raw image taken at 1300 nm in transillumination mode. The numerous dots are the camera artifacts at this wavelength. (B) Mask of the artifacts generated with MATLAB image segmenter. (C) Corrected Image; the mask is applied to the raw image to compensate at the artifacts locations.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

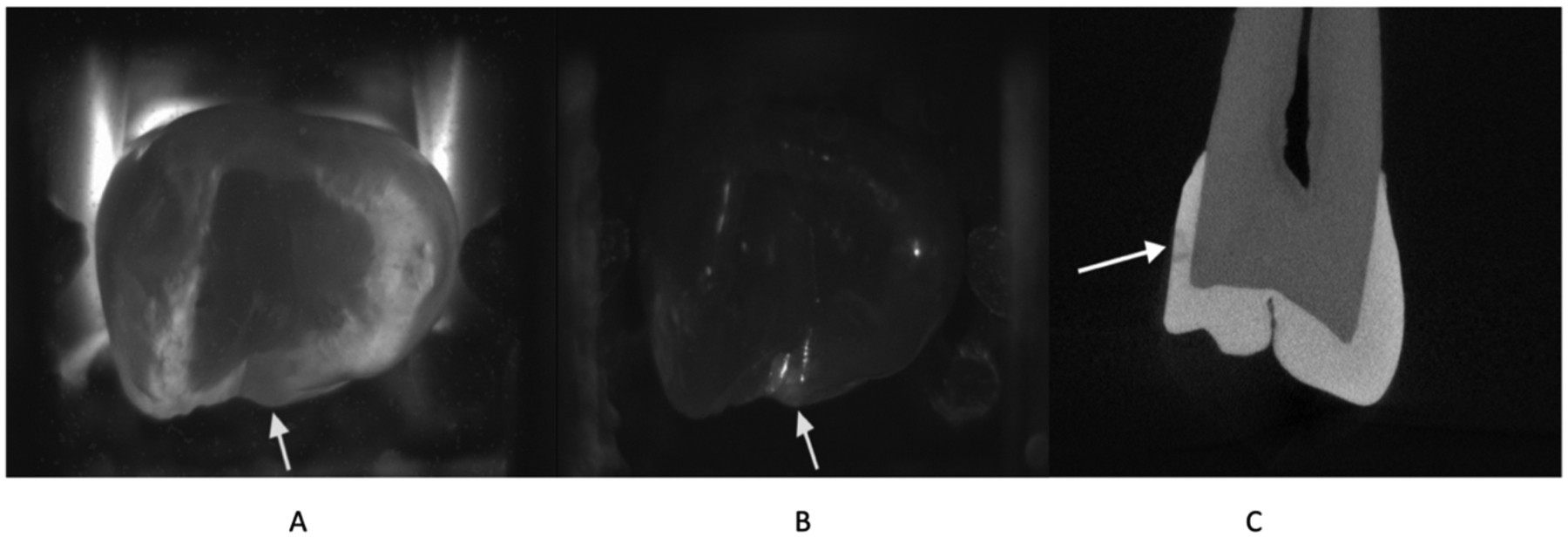

The dual probe performs well showing sharp images in both transillumination and reflectance modes. Figure 5 shows a set of transillumination/reflectance images taken by the dual probe compared with μCT, in which the approximal lesion can be seen in both images. The lesion appears darker in transillumination mode since the increased scattering by the lesion attenuates the light transmitted through the tooth, while it appears lighter in reflectance due to the scattered light from the lesion.

Fig 5.

A set of images taken by the dual probe. The approximal lesion shows good contrast in both modes, appearing dark in transillumination mode and bright in reflectance mode. (A) Transillumination mode. (B) Reflectance mode. (C) Micro-CT slice shows the approximal lesion.

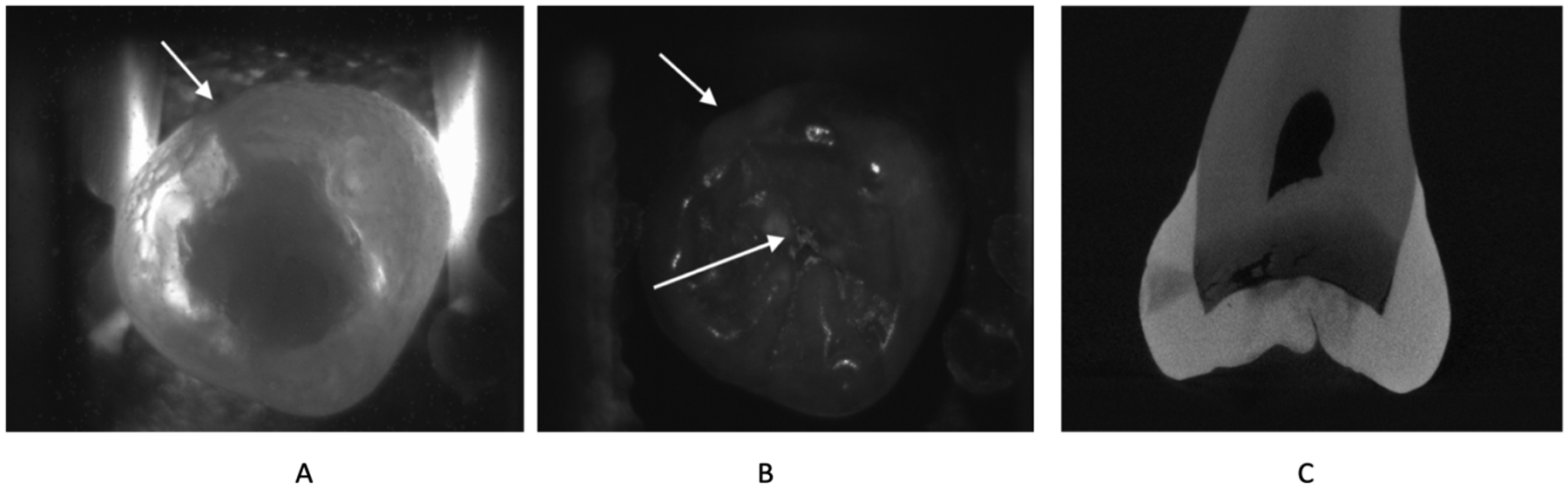

The 20 extracted teeth samples contain 28 lesions in total, including 19 approximal lesions and 9 occlusal lesions. All of the 19 approximal lesions could be seen in transillumination mode, and 5 lesions exhibited low contrast in the reflectance mode. All 9 occlusal lesions were visible in reflectance mode, and 2 lesions exhibited low contrast in the transillumination mode. Figure 6 shows a set of images in which the occlusal lesion shows poor contrast in transillumination mode, but the approximal lesion shows high contrast in both modes.

Fig 6.

The occlusal lesion isn’t visible in transillumination mode (A) Transillumination mode shows the approximal lesion but misses the occlusal lesion. (B) Reflectance mode shows both the approximal and the occlusal lesions. (C) μCT slice shows both lesions.

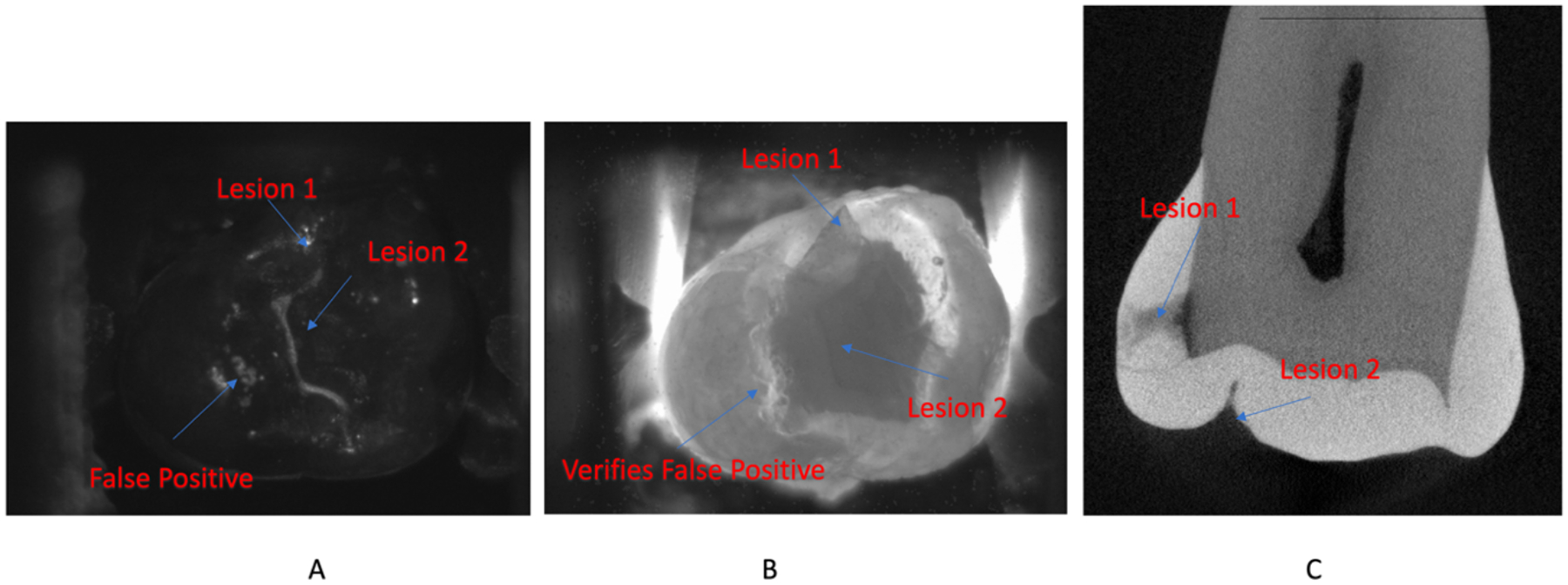

The dual probe also shows promising results verifying false positives. Figure 7 shows that there are three areas of high intensity visible in reflectance mode, but transillumination mode confirms that only two of them are lesions, and the other one is a false positive created by specular reflection.

Fig 7.

(A) Reflectance mode shows 3 hotspots due to potential lesions. (B) Transillumination mode verifies that one of them is a false positive, but the other two are indeed lesions. (C) μCT slice shows the two verified lesions.

Overall, transillumination mode yielded higher contrast (0.347 ± 0.079) for approximal lesions, while reflectance yielded higher contrast for occlusal lesions (0.647 ± 0.224).

The dual SWIR probe performs well in acquiring sharp in-vitro transillumination and reflectance SWIR images of extracted teeth. The probe is fabricated by a 3D printer and consists of 3 light sources including of a fiber source for reflectance at 1450 nm and 2 fibers for transillumination at 1300 nm. The transillumination mode performs well at detecting approximal lesions while the reflectance mode performs well at detecting occlusal lesions. The two modes complement each other for both types of lesions and possible false positives appearing in reflectance mode can be verified in transillumination mode. Having shown promising performance for in-vitro studies, the dual SWIR probe shows great potential for in-vivo usability. This probe will be used for future clinical studies.

4. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of NIDCR/NIH grants R01-DE028295 and F30-DE027264. The authors would like to thank Jacob Simon his contribution to this work.

5. REFERENCES

- [1].Buhler C, Ngaotheppitak P, and Fried D, “Imaging of occlusal dental caries (decay) with near-IR light at 1310-nm,” Optics Express, 13(2), 573–82 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Staninec M, Lee C, Darling CL, and Fried D, “In vivo near-IR imaging of approximal dental decay at 1,310 nm,” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, 42(4), 292–8 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jones G, Jones RS, and Fried D, “Transillumination of interproximal caries lesions with 830-nm light,” Lasers in Dentistry X. SPIE, Vol. 5313 17–22 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jones RS, Huynh GD, Jones GC, and Fried D, “Near-IR Transillumination at 1310-nm for the Imaging of Early Dental Caries,” Optics Express, 11(18), 2259–2265 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fried D, Featherstone JDB, Darling CL, Jones RS, Ngaotheppitak P, and Buehler CM, “Early Caries Imaging and Monitoring with Near-IR Light,” Dental Clinics of North America - Incipient and Hidden Caries, 49(4), 771–794 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hirasuna K, Fried D, and Darling CL, “Near-IR imaging of developmental defects in dental enamel.,” J Biomed Opt, 13(4), 044011: 1–7 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lee C, Lee D, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Nondestructive assessment of the severity of occlusal caries lesions with near-infrared imaging at 1310 nm,” Journal of Biomedical Optics, 15(4), 047011 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Karlsson L, Maia AMA, Kyotoku BBC, Tranaeus S, Gomes ASL, and Margulis W, “Near-infrared transillumination of teeth: measurement of a system performance,” J Biomed Optics, 15(3), 036001–8 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Simon JC, Lucas SA, Lee RC, Staninec M, Tom H, Chan KH, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Near-IR Transillumination and Reflectance Imaging at 1300-nm and 1500–1700-nm for in vivo Caries Detection,” Lasers Surg Med, 48(6), 828–836 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dye BA, Thornton-Evans T, Li X, and Iafolla TJ, Dental Caries and Tooth Loss in Adults in the United States, 2011–2012, (2015). [PubMed]

- [11].Dye BA, Tan S, Lewis BG, Barker LK, Thornton-Evans TG, Eke PI, Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Horowitz AM, and Li CH, “Trends in oral health status, United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004,” Vital Health Stat 11 2007;(248):1–92, 248, 1–92 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Funkhouser E, Bader JD, Gordan VV, Rindal DB, Pihlstrom DJ, Qvist V, and National Dental PCG, “Characteristics, detection methods and treatment of questionable occlusal carious lesions: findings from the national dental practice-based research network,” Caries Res, 48(3), 200–7 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Funkhouser E, Bader JD, Gordan VV, Rindal DB, Qvist V, Norrisgaard P, and National Dental PCG, “Twenty-month follow-up of occlusal caries lesions deemed questionable at baseline: findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network,” J Am Dent Assoc, 145(11), 1112–8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Funkhouser E, Bader JD, Gordan VV, Rindal DB, Bauer M, Pihlstrom DJ, Qvist V, and National G Dental Practice-Based Research Network Collaborative, “The prevalence of questionable occlusal caries: findings from the Dental Practice-Based Research Network,” J Am Dent Assoc, 143(12), 1343–50 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ng C, Almaz EC, Simon JC, Fried D, and Darling CL, “Near-infrared imaging of demineralization on the occlusal surfaces of teeth without the interference of stains,” J Biomed Optics, 24(3), 036002 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee C, Darling CL, and Fried D, “In vitro near-infrared imaging of occlusal dental caries using a germanium enhanced CMOS camera,” Lasers in Dentistry XVI. Proc SPIE Vol. 7549 K:1–7 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Simon JC, Curtis DA, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Multispectral near-infrared reflectance and transillumination imaging of occlusal carious lesions: variations in lesion contrast with lesion depth,” Lasers in Dentistry XXIV. Proc SPIE Vol. 10473 5:1–7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zakian C, Pretty I, and Ellwood R, “Near-infrared hyperspectral imaging of teeth for dental caries detection,” J J Biomed Optics, 14(6), 064047–7 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tom H, Simon JC, Chan KH, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Near-infrared imaging of demineralization under sealants,” J Biomed Opt, 19(7), 77003 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Simon JC, Lucas S, Lee R, Darling CL, Staninec M, Vanderhobli R, Pelzner R, and Fried D, “Near-infrared imaging of natural secondary caries,” Lasers in Dentistry XXI, Proc SPIE Vol. 9306 F:1–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lee RC, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Assessment of remineralization via measurement of dehydration rates with thermal and near-IR reflectance imaging,” J Dent, 43, 1032–1042 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lee RC, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Activity assessment of root caries lesions with thermal and near-infrared imaging methods,” J Biophotonics, 10(3), 433–445 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee RC, Staninec M, Le O, and Fried D, “Infrared methods for assessment of the activity of natural enamel caries lesions,” IEEE JSTQE, 22(3), 6803609 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hale GM, and Querry MR, “Optical constants of water in the 200-nm to 200-μm wavelength region.,” Appl Optics, 12, 555–563 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fried WA, Chan KH, Fried D, and Darling CL, “High Contrast Reflectance Imaging of Simulated Lesions on Tooth Occlusal Surfaces at Near-IR Wavelengths,” Lasers Surg Med, 45(8), 533–541 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mathworks, Username “Image Analyst”. (2017). freehand_masking_demo.m (r2018b). https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/answers/uploaded_files/84492/freehand_masking_demo.m