ABSTRACT

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a ubiquitous four-carbon, non-protein amino acid. GABA has been widely studied in animal central nervous systems, where it acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter. In plants, it is metabolized through the GABA shunt pathway, a bypass of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Additionally, it can be synthesized through the polyamine metabolic pathway. GABA acts as a signal in Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated plant gene transformation and in plant development, especially in pollen tube elongation (to enter the ovule), root growth, fruit ripening, and seed germination. It is accumulated during plant responses to environmental stresses and pathogen and insect attacks. A high concentration of GABA elevates plant stress tolerance by improving photosynthesis, inhibiting reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, activating antioxidant enzymes, and regulating stomatal opening in drought stress. The transporters of GABA in plants are reviewed in this work. We summarize the recent research on GABA function and transporters with the goal of providing a review of GABA in plants.

KEYWORDS: GABA, TCA cycle, plant growth and development, biotic and abiotic stress, carbon-nitrogen balance, signaling, transporters

1. Introduction

The potential impact of climate change on plant growth poses a serious threat to crop productivity and food security. Being sessile organisms, plants cannot move as animals can to seek more favorable environmental conditions for growth. They have to provide for themselves in one place as best they can to deal with the specific growth conditions they face and to keep pace with environmental change to ensure survival and growth. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is thus a molecule for the plant to deal with various growth environments.

GABA is a ubiquitous four-carbon non-proteinogenic amino acid found in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. In plants, GABA was first found in potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers more than 70 years ago.1 Henceforth, its physiological role has been widely studied2–12 and to date, it has been confirmed not only as a metabolite, but also as a signal molecule in plants.13–16 Its functional versatility includes responding to abiotic and biotic stress factors, maintaining carbon/nitrogen (C/N) balance, and regulating plant development. In this review, we discuss GABA metabolism, function, and transporters in plants.

2. The metabolic pathway and detection of GABA in plants

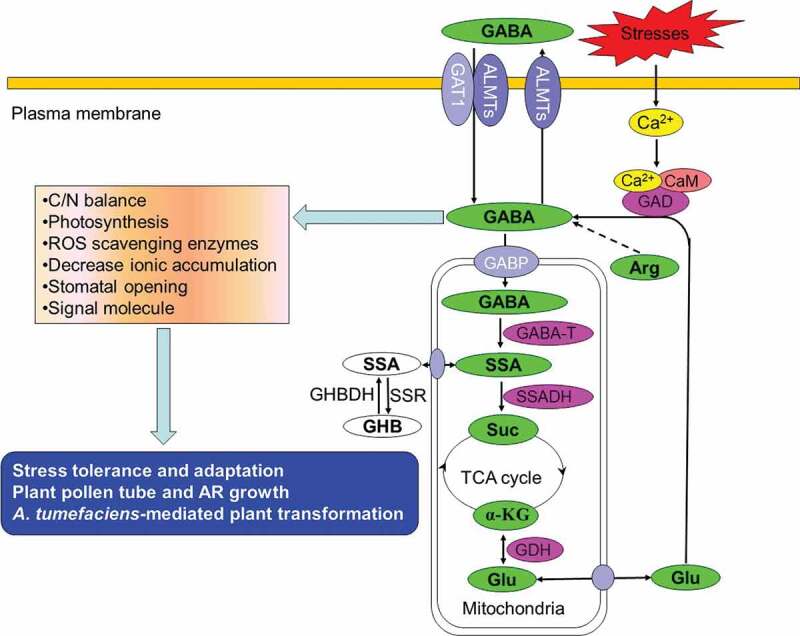

In plants, GABA is mainly involved in growth and development through the GABA shunt, a bypass of the TCA cycle. GABA is synthesized from glutamate by irreversible decarboxylation catalyzed by glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) in the cytosol. Subsequently, GABA is transferred into the mitochondria and subjected to transamination to succinic semialdehyde (SSA) by GABA transaminase (GABA-T/POP2). The SSA is then oxidized to succinate by the NAD+-dependent succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH), and subsequently succinate feeds into the TCA cycle. Thus, the carbon skeleton of glutamate ultimately enters the TCA cycle by this GABA shunt and recycles. In turn, glutamate can be synthesized from α-ketoglutarate by glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). Figure 1 is a simple illustration of GABA metabolism and functions (see review by Bouche & Fromm14).

Figure 1.

A simplified diagram of GABA metabolism and its roles in plants. GABA is synthesized from glutamate (Glu) or arginine (Arg) and transferred by GABA-permease (GABP) to mitochondria, where GABA is catabolized by GABA transaminase (GABA-T) and succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) to succinate (Suc). The succinate enters the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to maintain the C/N balance in cells. Glu can be synthesized by α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) via glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). SSA can also be converted to γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) through SSA reductase (SSR) and GHB can be changed to SSA via the GHB dehydrogenase (GHBDH). Diverse biotic and abiotic stress stimuli elicit an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels. A Ca2+/calmodulin complex activates GAD in the cytosol and GABA level increases. Transporters control the influx (GAT1, ALMTs, AAP3 or ProT2) and efflux (ALMTs) of GABA. Through various pathways, GABA regulates pollen tube and adventitious root (AR) growth and development and enhances plant stress tolerance

An alternative GABA-synthesis pathway is the polyamine metabolic pathway, where arginine is converted to putrescine through multi-step routes. Putrescine is then converted to 4-aminobutyraldehyde by O2-dependent polyamine oxidase or it is converted to spermidine, which degrades to 4-aminobutyraldehyde and in turn is oxidized to GABA by NAD+-dependent 4-aminobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase. GABA enters the TCA cycle to be degraded by GABA-T and SSADH (see review by Shelp et al).17

Tools to directly detect GABA in vivo have been developed and continue to be improved upon. Some GABA sensors that have been developed are based on Agrobacterium tumefaciens proteins Atu2422 and Atu4243. The Atu2422 protein has low affinity for GABA, and the Atu4243 protein fused with either cpGFP (circularly permuted green fluorescent protein) or cpSFGFP (cp-superfolder GFP) reportedly does not translocate to the membrane surface in HEK293 cells.18 A more recently developed fluorescent sensor, iGABASnFR, which uses Pf622, a homologue of Atu4243 found in Pseudomonas fluorescens and fused with cpGFP or cpSFGFP, was developed and could be used to detect GABA release in mice and zebrafish in vivo.18 It is difficult to find in the scientific literature reports of GABA sensors used in plants. Nevertheless, one group, Hijaz and Killiny (2020), reportedly used D6-GABA and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to investigate the uptake, translocation, and metabolism of exogenous GABA in Mexican lime (Citrus aurantifolia) seedlings.19

3. GABA acts as a signal molecule in plants

3.1. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-plant interaction

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a powerful tool for plant genetic engineering where researchers have taken advantage of its natural ability to transfer DNA within its Ti plasmid to transform plant cells it invades.20,21 After A. tumefaciens naturally invades a host plant, its T-DNA integrates into the plant’s genome and the transformed plant cells produce opines which induce crown gall disease. Opines upregulate the quorum-sensing (QS) system during tumor colonization. N-(3-oxooctanoyl) homoserine lactone (OC8-HSL) is degraded by Agrobacterium lactonase AttM and is the QS signal molecule22 that enhances conjugation of the Ti plasmid,23,24 the amplification of the Ti plasmid,25,26 and the severity of tumor symptoms.26 GABA rapidly accumulates in wounded plant tissues in response to biotic and abiotic stress conditions.14 In the Agrobacterium-plant interaction, GABA stimulates the degradation of the OC8-HSL by lactonase AttM27 and high concentrations of GABA in the tumor suppresses Ti plasmid conjugation.28 For example, a GABA-rich tobacco line was not as strongly affected by crown gall disease as the wildtype was affected.27 Furthermore, the crown gall symptoms were more severe in plants inoculated by an atu2422-mutated A. tumefaciens strain because they were unable to uptake GABA.29 In tomato, a low-GABA line exhibited greater T-DNA transfer frequency than its control.30 Moreover, inoculation by an A. tumefaciens strain with GABA-T activity to degrade GABA did not affect ploidy or copy number in two tomato cultivars and Erianthus arundinaceus.30 These results indicate that GABA inhibits T-DNA transfer and that GABA degradation during co-cultivation is an effective method for increasing T-DNA transfer.30 However, Lang et al. (2016) showed that higher accumulation of GABA in her1 (an Arabidopsis thaliana GABA-T/POP2 mutant line) suppressed vir gene expression, which is essential for T-DNA transfer.31 Therefore, some high levels of GABA accumulation may inhibit T-DNA transfer via vir gene suppression.

3.2. Plant development

In flowering plants, sexual reproduction is important for the completion of the plant life cycle. When a pollen grain lands on the surface of the stigma, polar growth of the pollen tube begins and allows the delivery of sperm cells into the ovule through the pollen tube. Proper guidance of pollen tube elongation is vital for plant mating. The concentration of GABA present in the flower can be a signal for pollen tube growth and orientation. GABA forms a gradient along the path of the pollen tube through the pistil and reaches the highest concentration near the micropyle, through which the pollen tube penetrates the ovule.13,32,33 POP2 encodes a GABA-T. In the flowers of a pop2 Arabidopsis mutant, growth of many pollen tubes is inhibited concomitantly with the presence of excessive GABA concentration and lack of a GABA gradient.32,34 Some pop2 tubes can grow toward the ovule, but they are misguided and cannot enter the ovule.13,32,33 Exogenous GABA can also affect pollen tube elongation in a dose-dependent manner as reported in Picea wilsonii.35 Pollen tube growth in P. wilsonii was observed under low and high concentrations of GABA, where low concentrations prompted pollen tube growth and an overdose of GABA inhibited tube growth.35 High GABA concentrations can also modulate pollen tube growth by impairing Ca2+ influx through Ca2+-permeable channels and GAD functions downstream of the Ca2+/CaM feedback control on Ca2+-permeable channels.36

GABA is also involved in fruit ripening. Under normal growing conditions, GABA highly accumulates at the mature green stage of fruits with immature seeds and then rapidly declines during ripening, when seeds in tomato fruits become mature.37 Down-regulation of the SlGAD genes in tomato reduces GABA levels and has little effect on normal plant growth and development.38 However, up-regulation of tomato SlGAD2 causes GABA levels to rise and stunts plant growth, delays flowering, and reduces flowering and fruit yield.39 In contrast, in over-expressing SlGAD3 tomato lines using the fruit-specific E8 promoter, high GABA levels were observed but no morphological abnormalities were recorded.40 Further, in C-terminal-truncated SlGAD3 OX lines, red-ripe fruits fail to develop due to a delay in ethylene production and a reduction of ethylene sensitivity.40

GABA is involved in seed gemination and primary and adventitious root growth. GABA levels increase in germination of soybean,41 oats,42 barnyard millet,43 adlay,44 rice,45 wheat,46,47 barley,48 and Chinese wild rice49 seeds. GABA activates α-amylase gene expression and promotes seed starch degradation in a dose-dependent pattern in seed germination.48 Excess GABA inhibits the elongation of primary roots and dark-grown hypocotyls.34 Exogenous GABA prevents seed germination and primary root growth in the recalcitrant seeds of Chinese chestnut by altering the balance of carbon and nitrogen metabolism to maintain the dormancy and storage of these seeds.50 Similarly, a high GABA content also inhibits adventitious root growth. For example, adventitious root growth of poplar is inhibited if the GABA level is increased in poplar lines by inhibition of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activity,51 overexpression of PagGAD2 52 or exogenous GABA application.51,52 The changes in GABA shunt activity affect cell-wall carbon metabolism-related genes and phytohormone (IAA, ABA, and ethylene) signaling.51,52

4. Abiotic and biotic stress

Unlike animals, plants are sessile organisms so they must obtain or produce their own resources to meet abiotic and biotic challenges through immobile means. Plants recruit many materials within themselves to respond to adverse conditions. GABA is one such material that accumulates rapidly in response to abiotic stress factors, such as low or high temperatures, drought, waterlogging, salt, hypoxia, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) content, and toxic heavy metals among others.4,14,53

4.1. Low temperature

Low temperature is one of the most significant limiting-factors of plant productivity. High concentrations of GABA in plants are often reported in response to cold stress. For example, GABA accumulates to a high extent and the expression of GABA shunt-related genes is induced during exposure of barley or wheat seedlings to cold or freezing temperatures.54 When hypoxia-treated sprouts were frozen at −18°C for 12 h and thawed at 25°C for 6 h, GABA content increased markedly to 7.21-fold higher levels than that in the unfrozen sprouts.55 Similarly, GABA increases to high levels in response to freezing stress in the perennial grass Brachypodium sylvaticum.56 Though many studies report high levels of GABA in response to low temperature exposure, GABA content in tea roots, on the other hand, decreases under cold treatment.57

High content of GABA is associated with plant tolerance to low temperatures. Exogenous GABA application induces an increase of endogenous GABA and improves cold tolerance in tomato seedlings,58 banana,59 anthurium cut-flowers,60 and tea plants.61 Potential mechanisms by which high levels of GABA alleviate low temperature injury may be due to enhancement of plant antioxidant systems,58,59 which reduces malondialdehyde (MDA) and ROS contents,58 and proline accumulation-mediated osmoregulation.59 Using iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis, researchers determined exogenous GABA-induced interactions among the biological processes of photosynthesis, amino acid biosynthesis, and C/N metabolism in tea plants.61 An increased level of GABA-shunt activity allowed GABA to participate in putrescine-induced acclimation to cold storage of zucchini fruit62 and in salicylic acid-mediated amelioration of postharvest chilling injury in anthurium cut-flowers.63 In nitric oxide (NO)-induced chilling tolerance, NO treatment increased the activities of diamine oxidase, polyamine oxidase and glutamate decarboxylase while reducing GABA-T activity to lower levels, which altogether resulted in GABA accumulation.64,65

4.2. High temperature

High temperature is an important factor that can limit plant growth and development and there are investigations of many different plant species’ relationships of heat stress and GABA. For example, in immature seeds of soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill) that had been heat-dried at a maximum temperature of 40°C, GAD was expressed at high levels and GABA-T and SSADH decreased rapidly during the heat-drying treatment. Consequently, GABA content in the treated seeds increased to more than five-fold (447.5 mg/100 g DW) the content in untreated seeds (79.6 mg/100 g DW).66 Similarly, GABA increases in ripening grapes67 and cell suspension cultures originated from pea-size ‘Gamy Red’ grape berries in response to elevated temperature68. Furthermore, heat stress generated an increase of glutamic acid in the cytoplasm69 that combined with calmodulin to activate GAD, thus producing high temperature-induced accumulation of GABA in Arabidopsis roots but not shoots.70

Studies indicate that GABA may serve a protective role in plants exposed to heat stress. The exogenous application of GABA to heat-stressed four-day-old rice (Oryza sativa) seedlings significantly increased growth and survival rates by improving leaf turgor and up-regulating osmoprotectants and antioxidants.71 Heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass effectively improved due to exogenous application of GABA, which is involved in regulating photosynthesis, osmotic potential, tricarboxylic acid cycle, metabolic homeostasis,69 enhancement of antioxidant defense systems,72 heat shock factors and heat shock proteins.73,74 Exogenous supplementation with GABA protects the reproductive functions (pollen germination, pollen viability, stigma receptivity, and ovule viability) of heat-stressed mungbean plants, and these plants produce greater weights of pods and seeds in comparison to those of the controls.75 Moreover, GABA application to heat-stressed plants also improves carbon fixation and assimilation and leaf water status by up-regulating the synthesis of osmolytes and thus reduces the oxidative damage.75

4.3. Drought

Drought is another highly restrictive factor for crop development and production and, similar to the stresses described above, promotes GABA accumulation. The excised leaves of turnip,76 bean,77 soybean78 and sesame79 plants subjected to drought stress raised their GABA levels. Drought has also been shown to induce high levels of GABA in tomato,80 Phyllanthus species,81 and creeping bentgrass.82 The Arabidopsis gad1/2 mutant has shown remarkably reduced GABA content, large stomata aperture, and defective stomata closure.83 Consequently, this mutant wilt earlier than the wildtype during a prolonged drought stress, whereas the functionally complemented gad1/2 × pop2 triple mutant exhibits the opposite in phenotype and also produces a higher GABA content.83 These results indicate that GABA accumulation during drought is a stress-specific response and helps regulate stomatal opening to prevent water loss.83 Increased endogenous GABA content by exogenous application improves white clover drought-tolerance via up-regulation of the GABA shunt, polyamines and proline metabolism.84 A high level of GABA also increases chlorophyll content, osmoregulation (i.e. soluble sugars, proline), and antioxidant enzyme activity in black cumin subjected to a water deficit.85 GABA enhancement of drought tolerance is associated with the improvement of nitrogen recycling, the protection of photosystem II, the mitigation of drought-depressed cell elongation, wax biosynthesis, fatty acid desaturase, and the delay of leaf senescence in creeping bentgrass.82 Drought and heat often occur simultaneously; in such case, as well as under drought alone, SSADH was identified as a metabolic quantitative trait loci (mQTL) in the barley flag-leaf.86

4.4. Flooding

Flooding severely affects crop yield.87 Globally, it is estimated that 12% of cultivated land is affected by waterlogging, resulting in a 20% decrease in crop production.88,89 Waterlogging reduces photosynthetic rate and antioxidant enzyme activity by causing damage to the protective enzymes90,91 and ultimately limits plant growth.92,93 In water-logged individuals of soybean94 and grape plants,95 GABA markedly accumulates in the nodules of the root systems. Further, GABA promotes the growth of maize seedlings in waterlogged conditions by downregulating reactive oxygen intermediates-producing enzymes, activating antioxidant enzymes, and improving chloroplast ultrastructure and photosynthetic traits.96

Hypoxic conditions resulting from soil waterlogging exacerbate the negative effects of the latter on plant growth and crop production. Hypoxia has been shown to induce GABA accumulation in plants.97–100 When applesand germinating fava bean101, Finally, the GABA shunt is considered partly responsible for alanine accumulation under hypoxia.102, Finally, the GABA shunt is considered partly responsible for alanine accumulation under hypoxia.102–106 soybean,, seeds experience hypoxia, GABA content increases greatly and decreases after termination of the stress. Under hypoxic conditions, glutamate decarboxylase and diamine oxidase activities increase, which in turn elevates plant GABA content.

4.5. Salt

Soil salinity is a major environmental stress that affects crop yield around the world.107Three cellular responses of salt tolerance have been proposed in plants: (i) osmotic stress tolerance, (ii) Na+ exclusion capacity and (iii) tissue tolerance to Na+ accumulation. Multiple studies have reported a variety of protective molecules that accumulate in plants and the mechanisms underlying plant response to salinity.107–109 The GABA-T-deficient pop2-1 mutant is sensitive to salt but not to osmotic stress,110 and the genes involved in cell-wall and carbon metabolism, particularly sucrose and starch catabolism, increase under salt stress.111 In contrast to the results observed for pop2-1, the pop2-5 mutant over-accumulated GABA in roots and exhibited salt tolerance rather than salt sensitivity.112 The different results of the different pop2 mutants may be due to their respective GABA levels, where one may have accumulated an excessive amount of GABA beyond a particular threshold that is harmful to plants.112 Using the mutants pop2-5 and gad1,2 (with reduced ability of GABA production), Su et al. (2019) showed that GABA induces H+-ATPase activation and reduces Na+ uptake, H2O2-induced K+ efflux and ROS concentration.112 Consistent with those results, GABA accumulation was also induced in Nicotiana sylvestris and cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) II plants treated with short- and long-term salt stress, but GAD activity did not correlate with GABA content.113 Contrary to this study, GABA content in Nicotiana tabacum plants treated with 500 mM NaCl decreased on the first and third day and increased on the seventh day of salt treatment.114 This may be due to the high level of salinity and a difference in plant development stage.113 GABA and GAD mRNA levels increase markedly in five wheat cultivars and poplar under saline conditions.115,116 In salt-treated wheat leaves, key metabolic enzymes required for the cyclic operation of the TCA cycle reportedly were physiochemically inhibited by salt, but the increase in GABA shunt activity provided an alternative carbon source for the TCA cycle to function in mitochondria and bypassed salt-sensitive enzymes to facilitate the increase in leaf respiration in wheat plants.117 Further, the application of exogenous GABA to maize,118 white clover,119 muskmelon,120 germinated hull-less barley,121 and tomato122 increases endogenous GABA content, activates enzymatic antioxidant activity, alleviates salt damage to plants, and enhances plant salt-tolerance.

GABA accumulation in plants in response to salinity is also associated with other stresses and hormones. GABA accumulated in durum wheat under salinity treatment combined with high nitrogen or high light treatment and GABA could also serve as a temporary place of nitrogen storage.123 Application of GABA to plants exposed to NaCl affects the production of H2O2, ABA, and ethylene.124,125 Moreover, 22 ABA- and 50 ethylene-related genes have been shown to be regulated by exogenous GABA.125

4.6. Heavy metal

Heavy metals are major pollutants in soils and can contaminate food due to their accumulation in the edible parts of crop plants. Besides ion toxicity, ROS accumulation is a common phenomenon accompanied by heavy metal stress.126 A metabolome analysis showed that GABA content increases during chromium (Cr) stress in rice roots.127 Similarly, when soybean is grown under zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu) stress, high levels of GABA have been observed.128 Nicotiana tabacum plants treated with intermediate (10 µM) Zn concentrations showed highly induced levels of GABA but low levels when treated with high (100 µM) Zn concentrations.129 When rice seedlings grew under arsenic (As (III)) stress, GABA application induced GABA-shunt-related gene expression, activated the antioxidant enzyme system, and strongly inhibited As accumulation, thus conferring a tolerance to As (III) in the seedlings.130 Interestingly, long-term accumulation of GABA is more highly efficient in inducing As (III) tolerance than higher GABA levels in the short term, which actually causes toxicity.130 On the other hand, Cd stress seemingly reduces endogenous GABA content in duckweed, and under Cd stress, exogenous GABA enhanced rhizoid abscission, whereas Glu addition promotes rhizoid abscission.131 GAD genes are uniformly up-regulated in maize and rice roots by Cd stress, and the overexpression of ZmGAD1 and ZmGAD2 in Cd-sensitive yeast and tobacco leaves enhances Cd tolerance in the host cells.132 All of the aforementioned studies indicate that GABA content does not always increase in response to different metal stresses and may be more related to metal concentrations. Furthermore, high GABA content does not always enhance plant tolerance to metal stress.

4.8. ROS

A range of abiotic stress conditions can enhance the accumulation of ROS in plants. When the GABA shunt functions in response to abiotic stress, it effectively restricts ROS generation in plant tissues. Succinic-semialdehyde dehydrogenase is the enzyme that catalyzes the last step in the GABA shunt. Four T-DNA insertion mutants of SSADH (ssadh mutants) have been shown to be phenotypically dwarfed with necrotic lesions, bleached leaves, reduced leaf area, lower chlorophyll content, shorter hypocotyls, and fewer flowers.133 These ssadh mutants are sensitive to heat and UV stress and accumulate high levels of ROS, causing cell death in tissues exposed to the stress.133 A five-fold greater amount of GHB (γ-hydroxybutyrate, a by-product of SSA) was reported in ssadh mutants than in wildtype Arabidopsis.134 Treatment with γ-vinyl-γ-aminobutyrate, a specific inhibitor of GABA-T/POP2, or a mutation of the POP2 gene prevents the accumulation of ROS in ssadh mutants, inhibits cell death, and improves growth.134,135 The phenotype of ssadh tomato mutants (SlSSADH-silenced plants by the VIGS system) shows stunted growth, curled leaves, and hyper-accumulation of ROS, thus resembling Arabidopsis ssadh mutants.136 Succinic semialdehyde can be converted into GHB by SSA reductase, and GHB can be converted into SSA by GHB dehydrogenase in animals and plants (Figure 1). Because SSA cannot be converted to succinate by SSADH in ssadh mutants, SSA and/or GHB accumulates.134,135 In pop2 and pop2ssadh mutants, GABA levels are four and five times higher than that in wild type plants.135 However, the phenotypes of double pop2ssadh mutants revert to that of the wild type, indicating that the high GABA content is not the cause of the phenotype of ssadh mutants.135 The ssadh mutants are more sensitive to SSA, and pop2ssadh mutants are more sensitive to SSA or GHB than are wild type or pop2 mutants, indicating that high levels of SSA and/or GHB and not GABA levels cause the observed phenotype of ssadh mutants.135

4.9. Biotic stress

During plant growth and development, plants face a diversity of pathogens and pests. Plant GABA levels have also been shown to increase in response to biotic stress.10,137 For example, in cultured rice cells treated with a cell-wall elicitor of rice blast fungus (Magnaporthe grisea), the level of GABA increased 12.5-fold at 8 hours after treatment.138 Similarly, GABA production is highly induced in stems of Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae) infected with the Jatropha mosaic virus (JMV),139 in tomato leaves infected by Botrytis cinereal,140 in tobacco leaves infiltrated with a hairpin elicitor,141 in leaves of potato plants after inoculation with potato virus Y,142 in leaf apoplast of Phaseolus vulgaris inoculated with P. syringae pv. phaseolicola (Pph) 1302A,143 in Arabidopsis infected with Fusarium graminearum,144 in diseased Vitis vinifera,145 and in lettuce inoculated with gray mold.146 ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ and its vector, Diaphorina citri can accelerate cytosolic accumulation of GABA in citrus.147 Conversely, a comparative proteomic analysis showed a significant down-regulation of GABA biosynthesis in tomato stems inoculated with highly and mildly aggressive Ralstonia solanacearum isolates.148,149 This result is consistent with a transcriptome profiling showing GABA shunt-related genes GAD2 and SSADH1 knocked-down by VIGS.148 In addition, GABA accumulation decreases the biomass and toxicity of Lasiodiplodia theobromae and the metabolites produced by L. theobromae.150 In plants, GABA plays an important role in central C/N metabolism by connecting amino acid metabolism to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (see the detailed text in section 5 “C: N balance” below). In plant–microbe interactions, GABA contents increase due to the elevated GAD enzyme activity.141,149 Then GABA enters into the TCA cycle to maintain cell viability via alteration in C: N metabolism.139,140 Consequently, GABA activates antioxidant enzymes (peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase) and limits the cell death that can be caused by excessive ROS.151 Thus, high GABA levels indicate plant resistance to pathogens.

Reportedly, GABA is also involved in plant defense against herbivorous insects.152–154 For example, in GABA-reduced (gad1/2 double mutant) and GABA-enriched (gad1/2ⅹpop2-5) A. thaliana mutants, wounding of plant tissues and cell disruption caused by insect herbivory is sufficient to induce rapid, systemic, jasmonate (JA)-independent GABA synthesis and accumulation.155 However, in the responses of Clematis terniflora D. C. to UVB radiation and darkness, over-accumulation of JA leads to a remarkable increase in GABA content.156 In addition, high contents of GABA may be a plant defense against insects as GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter in invertebrate nervous systems.137

In summary, a common response to stress in plants is the immediate elicited increase of Ca2+ concentration. The Ca2+/calmodulin complex is perceived by GAD in the cytosol and GABA accumulates. Then, GABA is degraded and enters the TCA cycle to maintain C/N balance as a metabolite or GABA inhibits ROS accumulation by activating antioxidant enzymes in plants. GABA may also be a signal to activate other molecules in plant response to stresses. In brief, stress induces high levels of GABA accumulation in plants and high GABA concentrations improve plant resistance to stress.

5. C: N balance

Carbon and nitrogen are the major essential elements for plants. Efficient assimilation of C and N is essential for optimal plant growth, productivity, and yield.157 Carbon skeletons enter the TCA cycle through the GABA shunt, whereby GABA can function as a nitrogen storage metabolite in plants. For example, A. thaliana can grow well on a culture medium containing GABA as the sole nitrogen source.158 Nitrogen-deficiency by excision of 50% of the nodules from Medicago truncatula causes the concentration of GABA in phloem exudates to almost triple.159 After artificial petiole-feeding with GABA, the GABA concentration in nodules increases significantly, the concentration of glutamate declines in phloem exudates and N2 fixation recovers 4–5 days after excision.159 In the process of seed “maturation-drying” in Arabidopsis, GABA initially accumulates to a high level and then decreases upon germination.160–162 In truncated-GAD transgenic Arabidopsis, GABA accumulates in dry seeds, while the concentration of a number of sugars and organic acids decrease, and numerous amino acids and total protein significantly accumulate. 162 These results show that deregulated GAD alters the N to C ratio in Arabidopsis seeds.162 Additionally, the obstruction of the GABA shunt leads to significant changes in sucrose and starch contents and affects carbon metabolism in the cell wall.111 Therefore, GABA is rightfully considered to represent the central position in the interface between plant carbon and nitrogen metabolisms.163 Under low-nitrogen conditions, exogenous GABA application increases the non-structural carbon hydrates and TCA intermediates in the stems of poplar seedlings.164 Moreover, GABA significantly attenuates the low nitrogen-induced increase of leaf antioxidant enzymes, which suggests that GABA affects the C:N ratio for poplar growth by reducing energy costs under N-deficient conditions.164

6. GABA transporters in plants

GABA can be transported across the plasma membrane and organelle membranes. In these processes, both intra- and intercellular transport of GABA is likely required. GABA transporters were first identified in animals165 and then identified in plants in 1999.158 Arabidopsis thaliana grows efficiently with GABA as its sole nitrogen source, thereby providing evidence for the existence of GABA transporters in plants.158 Two low-affinity GABA transporters (amino acid permease 3, AAP3, and proline transporters 2, ProT2) from A. thaliana were identified by heterologous complementation in yeast, and these two GABA transporters can transport proline as well.158 A high-affinity GABA influx transporter in A. thaliana, AtGAT1, has been characterized through heterologous expression systems, i.e., Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Xenopus laevis oocytes.166 AtGAT1, localized at the plasma membrane, shares no sequence similarity with any of the non-plant GABA transporters described to date, and it expresses to the highest recorded levels in flowers and upon wounding or during senescence.166 GABA accumulates in the cytosol in response to various stress conditions and is transported into the mitochondria, where it is catabolized. A mitochondrial GABA-transporter (AtGABP, GABA-permease) that mediates transport of GABA from the cytosol into the mitochondrion has been functionally characterized in Arabidopsis by complementation in yeast and Arabidopsis gabp mutants.167 The gabp mutants grow abnormalities under limited-carbon availability on artificial media and in soil under low light intensity.167

Although influx transporters of GABA in plants have been characterized as aforementioned, a GABA-efflux transporter that transports GABA from the cytosol to the apoplast was identified recently in wheat.53,168–170 Plant ALMTs (aluminum-activated malate transporters), classified as anion channels and regulated by diverse signals, are activated by anions and negatively regulated by GABA.168,171 GABA-mediated TaALMT1 activity results in altered root growth and altered root tolerance to alkaline pH, acid pH, and aluminum ions.168 Plant ALMTs from wheat, barley, rice, and Arabidopsis can transport GABA into cells.170 TaALMT1 facilitates GABA efflux and influx at very high rates.170 Ion of Al3+ activates malate and GABA efflux at low pH but blocks TaALMT1-mediated GABA influx. However, the reduction in GABA content in response to Al3+ at low pH and to anions at high pH is due to the large GABA efflux caused by activated TaALMT1, bearing no relation to malate efflux.170 GABA seemingly exerts its multiple physiological effects in plants via ALMT, including the regulation of pollen tube and root growth. The uptake of GABA by AtGAT1 is not reduced in response to Al3+.170 However, GABA can inhibit anion transport by TaALMT1 from the inside and outside of a cell.172,173 The molecular mechanism may resemble the conformational transition of GabR when binding to the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent aspartate aminotransferase (AAT) and GABA.174 It is possible that GABA causes the TaALMT1 active structure to make a conformational transition and render TaALMT1 unable to transport anions.173

7. Conclusions and future perspectives

Plant GABA was first reported in 1949 from potato tubers.1 As described above, GABA accumulates in response to different kinds of biotic and abiotic stress, and it regulates plant growth and development. Stress factors also rapidly elicit a transient increase of cytosolic Ca2+ levels. Ca2+ is the universal second messenger in stress signaling.109 The Ca2+/calmodulin system activates GAD in the cytosol and concomitantly, GABA levels increase.6 Alternatively, GABA is synthesized from arginine through multiple steps. Then, GABA is transported into mitochondria by GABP and enters the TCA cycle to maintain C/N balance in cells. GABA influx is controlled by transporters GAT1, ALMTs, AAP3, or ProT2, and GABA efflux occurs by ALMTs. In cells, GABA facilitates photosynthesis, inhibits ROS generation, and activates antioxidant enzymes. GABA also regulates stomatal opening in drought stress and acts as a signal molecule in plants in order to regulate plant growth and development and elevate stress tolerance.

Recently, considerable progress has been made regarding GABA transporters; GABA regulation of adventitious root growth, primary root growth, and seed germination; and GABA responses to stress. However, many questions remain unclear or controversial. For instance, when plants experience a stress, how do they maintain balance between high GABA levels and plant growth? How do plant hormones interact with GABA? Clearly, GABA plays many roles in plants, but how does the signal pathway(s) of GABA operate(s) in plants? What is the component that senses GABA levels? What is the relationship between GABA and ROS? We hope ongoing and future research will provide the answers to these questions in the near future.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation(ZR201709280123) and the Innovation Project of Top Ten Agricultural Characteristic Industrial Science and Technology of Ji’nan.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution statement

Chunxia Wu, Li Li and Na Dou wrote this manuscript; Chunxia Wu and Hui Zhang were involved in preparing figures and revising this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Steward FC, Thompson JF, Dent CE.. γ-Aminobutyric acid: a constituent of the potato tuber? Science. 1949;110:1–12.17753806 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bown AW, Shelp BJ.. The metabolism and functions of γ-aminobutyric acid. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1–5. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shelp BJ, Bown AW, McLean MD. Metabolism and functions of gamma-aminobutyric acid. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:446–452. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(99)01486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinnersley AM, Turano FJ. Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and plant responses to stress. Critic Rev Plant Sci. 2000;19(6):479–509. doi: 10.1080/07352680091139277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fait A, Fromm H, Walter D, Galili G, Fernie AR. Highway or byway: the metabolic role of the GABA shunt in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shelp BJ, Bozzo GG, Trobacher CP, Chiu G, Bajwa VS. Strategies and tools for studying the metabolism and function of γ-aminobutyrate in plants. I Pathway Structure Botany. 2012;90:651–668. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelp BJ, Bozzo GG, Zarei A, Simpson JP, Trobacher CP, Allan WL. Strategies and tools for studying the metabolism and function of γ-aminobutyrate in plants. II Integr Anal Bot. 2012;90:781–793. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rashmi D, Zanan R, John S, Khandagale K, Nadaf A. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA): biosynthesis, role, commercial production, and applications. Stud Nat Prod Chem. 2018;57:413–452. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos-Ruiz R, Martinez F, Knauf-Beiter G, Tejada Moral M. The effects of GABA in plants. Cogent Food Agricul. 2019;5(1):1670553. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2019.1670553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seifikalhor M, Aliniaeifard S, Hassani B, Niknam V, Lastochkina O. Diverse role of γ‑aminobutyric acid in dynamic plant cell responses. Plant Cell Rep. 2019;38:847–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bown AW, Shelp BJ. Does the GABA shunt regulate cytosolic GABA? Trends Plant Sci. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gramazio P, Takayama M, Ezura H. Challenges and prospects of new plant breeding techniques for GABA improvement in crops: tomato as an example. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:577980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma H. Plant reproduction: GABA gradient, guidance and growth. Curr Biol. 2003;13:R834–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouche N, Fromm H. GABA in plants: just a metabolite? Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bown AW, Shelp BJ. Plant GABA: not just a metabolite. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:811–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fromm H. GABA signaling in plants: targeting the missing pieces of the puzzle. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(20):6238–6245. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shelp BJ, Bozzo GG, Trobacher CP, Zarei A, Deyman KL, Brikis CJ. Hypothesis/review: contribution of putrescine to 4-aminobutyrate (GABA) production in response to abiotic stress. Plant Sci. 2012;193-194:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marvin JS, Shimoda Y, Magloire V, Leite M, Kawashima T, Jensen TP, Kolb I, Knott EL, Novak O, Podgorski K, et al. A genetically encoded fluorescent sensor for in vivo imaging of GABA. Nat Methods. 2019;16(8):763–770. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hijaz F, Killiny N. The use of deuterium-labeled gamma-aminobutyric (D6-GABA) to study uptake, translocation, and metabolism of exogenous GABA in plants. Plant Methods. 2020;16:24. doi: 10.1186/s13007-020-00574-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereira A. A transgenic perspective on plant functional genomics. Transgenic Res. 2000;9:245–260. doi: 10.1023/A:1008967916498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tyagi AK, Mohanty A. Rice transformation for crop improvement and functional genomics. Plant Sci. 2000;158:1–18. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piper KR, von Bodman SB, Hwang I, Farrand SK. Hierarchical gene regulatory systems arising from fortuitous gene associations: controlling quorum sensing by the opine regulon in Agrobacterium. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32(5):1077–1089. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piper KR, Von Bodman SB, Farrand SK. Conjugation factor of Agrobacterium tumefaciens regulates Ti plasmid transfer by autoinduction. Nature. 1993;362(6419):448–450. doi: 10.1038/362448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Murphy PJ, Kerr A, Tate ME. Agrobacterium conjugation and gene regulation by N-acyl-L-homoserine lactones. Nature. 1993;362(6419):446–448. doi: 10.1038/362446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li PL, Farrand SK. The replicator of the nopaline-type Ti plasmid pTiC58 is a member of the repABC family and is influenced by the TraR-dependent quorum-sensing regulatory system. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pappas KM, Winans SC. A LuxR‐type regulator from Agrobacterium tumefaciens elevates Ti plasmid copy number by activating transcription of plasmid replication genes. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1059–1073. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chevrot R, Rosen R, Haudecoeur E, Cirou A, Shelp BJ, Ron E, Faure D. GABA controls the level of quorum-sensing signal in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Pro Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7460–7464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deeken R, Engelmann JC, Efetova M, Czirjak T, Müller T, Kaiser WM, Tietz O, Krischke M, Mueller MJ, Palme K, et al. An integrated view of gene expression and solute profiles of Arabidopsis tumors: a genome-wide approach. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3617–3634. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haudecoeur E, Planamente S, Cirou A, Tannieres M, Shelp BJ, Morera S, Faure D. Proline antagonizes GABA-induced quenching of quorum-sensing in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Pro Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(34):14587–14592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nonaka S, Someya T, Zhou S, Takayama M, Nakamura K, Ezura H. An Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain with gamma-aminobutyric acid transaminase activity shows an enhanced genetic transformation ability in plants. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):42649. doi: 10.1038/srep42649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang J, Gonzalez-Mula A, Taconnat L, Clement G, Faure D. The plant GABA signaling downregulates horizontal transfer of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence plasmid. New Phytol. 2016;210:974–983. doi: 10.1111/nph.13813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palanivelu R, Brass L, Edlund AF, Preuss D. Pollen tube growth and guidance is regulated by POP2, an Arabidopsis gene that controls GABA levels. Cell. 2003;114(1):47–59. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Z. GABA, a new player in the plant mating game. Dev Cell. 2003;5:185–186. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renault H, El Amrani A, Palanivelu R, Updegraff EP, Yu A, Renou J-P, Preuss D, Bouchereau A, Deleu C. GABA accumulation causes cell elongation defects and a decrease in expression of genes encoding secreted and cell wall-related proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52:894–908. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ling Y, Chen T, Jing Y, Fan L, Wan Y, Lin J. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) homeostasis regulates pollen germination and polarized growth in Picea wilsonii. Plant. 2013;238:831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu GH, Zou J, Feng J, Peng XB, Wu JY, Wu YL, Palanivelu R, Sun MX. Exogenous gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) affects pollen tube growth via modulating putative Ca2+-permeable membrane channels and is coupled to negative regulation on glutamate decarboxylase. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:3235–3248. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takayama M, Ezura H. How and why does tomato accumulate a large amount of GABA in the fruit? Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takayama M, Koike S, Kusano M, Matsukura C, Saito K, Ariizumi T, Ezura H. Tomato glutamate decarboxylase genes SlGAD2 and SlGAD3 play key roles in regulating γ-aminobutyric acid levels in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56(8):1533–1545. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nonaka S, Arai C, Takayama M, Matsukura C, Ezura H. Efficient increase of ɣ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) content in tomato fruits by targeted mutagenesis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7057. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06400-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takayama M, Matsukura C, Ariizumi T, Ezura H. Activating glutamate decarboxylase activity by removing the autoinhibitory domain leads to hyper γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) accumulation in tomato fruit. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuyama A, Yoshimura K, Shimizu C, Murano Y, Takeuchi H, Ishimoto M. Characterization of glutamate decarboxylase mediating γ-amino butyric acid increase in the early germination stage of soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr). J Biosci Bioeng. 2009;107:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu JG, Hu QP, Duan JL, Tian CR. Dynamic changes in gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate decarboxylase activity in oats (Avena nuda L.) during steeping and germination. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(17):9759–9763. doi: 10.1021/jf101268a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma S, Saxena DC, Riar CS. Analysing the effect of germination on phenolics, dietary fibres, minerals and γ-aminobutyric acid contents of barnyard millet (Echinochloa frumentaceae). Food Biosci. 2016;13:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2015.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu L, Chen L, Ali B, Yang N, Chen Y, Wu F, Jin Z, Xu X. Impact of germination on nutritional and physicochemical properties of adlay seed (Coixlachryma-jobi L.). Food Chem. 2017;229:312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao GC, Xie MX, Wang YC, Li JY. Molecular mechanisms underlying γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) accumulation in giant embryo rice seeds. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65:4883–4889. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim MJ, Kwak HS, Kim SS. Effects of germination on protein, γ-aminobutyric acid, phenolic acids, and antioxidant capacity in wheat. Molecules. 2018;23(9). doi: 10.3390/molecules23092244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.AL-Quraan NA, AL-Ajlouni ZI, Obedat DI. The GABA shunt pathway in germinating seeds of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) under salt stress. Seed Sci Res. 2019;29:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0960258519000230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheng Y, Xiao H, Guo C, Wu H, Wang X. Effects of exogenous gamma-aminobutyric acid on α-amylase activity in the aleurone of barley seeds. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018;127:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chu C, Yan N, Du Y, Liu X, Chu M, Shi J, Zhang H, Liu Y, Zhang Z. iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis reveals the accumulation of bioactive compounds in Chinese wild rice (Zizania latifolia) during germination. Food Chem. 2019;289:635–644. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du C, Chen W, Wu Y, Wang G, Zhao J, Sun J, Ji J, Yan D, Jiang Z, Shi S. Effects of GABA and vigabatrin on the germination of Chinese chestnut recalcitrant seeds and its implications for seed dormancy and storage. Plants (Basel). 2020;9:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yue J, Du C, Ji J, Xie T, Chen W, Chang E, Chen L, Jiang Z, Shi S. Inhibition of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activity affects adventitious root growth in poplar via changes in GABA shunt. Plant. 2018;248(4):963–979. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-2929-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie T, Ji J, Chen W, Yue J, Du C, Sun J, Chen L, Jiang Z, Shi S. GABA negatively regulates adventitious root development in poplar. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(4):1459–1474. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramesh SA, Tyerman SD, Gilliham M, Xu B. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) signalling in plants. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74:1577–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazzucotelli E, Tartari A, Cattivelli L, Forlani G. Metabolism of γ-aminobutyric acid during cold acclimation and freezing and its relationship to frost tolerance in barley and wheat. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:3755–3766. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang R, Feng L, Wang S, Yu N, Gu Z. Accumulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid in soybean by hypoxia germination and freeze-thawing incubation. J Sci Food Agric. 2016;96(6):2090–2096. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toubiana D, Sade N, Liu L, Rubio Wilhelmi MDM, Brotman Y, Luzarowska U, Vogel JP, Blumwald E. Correlation-based network analysis combined with machine learning techniques highlight the role of the GABA shunt in Brachypodium sylvaticum freezing tolerance. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Xiong F, Nong S, Liao J, Xing A, Shen Q, Ma Y, Fang W, Zhu X. Effects of nitric oxide on the GABA, polyamines, and proline in tea (Camellia sinensis) roots under cold stress. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12240. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69253-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malekzadeh P, Khara J, Heydari R. Alleviating effects of exogenous Gamma-aminobutyric acid on tomato seedling under chilling stress. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2014;20:133–137. doi: 10.1007/s12298-013-0203-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, Luo Z, Huang X, Yang K, Gao S, Du R. Effect of exogenous γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) treatment on chilling injury and antioxidant capacity in banana peel. Sci Hortic. 2014;168:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aghdam MS, Naderi R, Jannatizadeh A, Babalar M, Sarcheshmeh MA, Faradonbe MZ. Impact of exogenous GABA treatments on endogenous GABA metabolism in anthurium cut flowers in response to postharvest chilling temperature. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;106:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu X, Liao J, Xia X, Xiong F, Li Y, Shen J, Wen B, Ma Y, Wang Y, Fang W. Physiological and iTRAQ-based proteomic analyses reveal the function of exogenous γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in improving tea plant (Camellia sinensis L.) tolerance at cold temperature. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palma F, Carvajal F, Ramos JM, Jamilena M, Garrido D. Effect of putrescine application on maintenance of zucchini fruit quality during cold storage: contribution of GABA shunt and other related nitrogen metabolites. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2015;99:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aghdam MS, Naderi R, Malekzadeh P, Jannatizadeh A. Contribution of GABA shunt to chilling tolerance in anthurium cut flowers in response to postharvest salicylic acid treatment. Sci Hortic. 2016;205:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2016.04.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang C, Tang D, Gao YG, Zhang LH. Succinic semialdehyde promotes prosurvival capability of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 2016;198:930–940. doi: 10.1128/JB.00373-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang D, Li L, Xu Y, Limwachiranon J, Li D, Ban Z, Luo Z. Effect of exogenous nitro oxide on chilling tolerance, polyamine, proline, and gamma-aminobutyric acid in bamboo shoots (Phyllostachys praecox f. prevernalis). J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65:5607–5613. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takahashi Y, Sasanuma T, Abe T. Accumulation of gamma-aminobutyrate (GABA) caused by heat-drying and expression of related genes in immature vegetable soybean (edamame). Breed Sci. 2013;63:205–210. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.63.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sweetman C, Sadras VO, Hancock RD, Soole KL, Ford CM. Metabolic effects of elevated temperature on organic acid degradation in ripening Vitis vinifera fruit. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:5975–5988. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ayenew B, Degu A, Manela N, Perl A, Shamir MO, Fait A. Metabolite profiling and transcript analysis reveal specificities in the response of a berry derived cell culture to abiotic stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:728. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Z, Yu J, Peng Y, Huang B. Metabolic pathways regulated by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) contributing to heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). Sci Rep. 2016;6:30338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Locy RD, Wu SJ, Bisnette J, Barger TW, Mcnabb D, Zik M, Fromm H, Singh NK, Cherry JH. The regulation of GABA accumulation by heat stress in Arabidopsis. In: Plant tolerance to abiotic stresses in agriculture: role of genetic engineering. Eds. Joe H. CherryRobert D. LocyAnna Rychter. NATO Science Series (Series 3: High Technology), Vol. 183. The Netherlands, Dordrecht: Springer; 2000. p. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nayyar H, Kaur R, Kaur S, Singh R. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) imparts partial protection from heat stress injury to rice seedlings by improving leaf turgor and upregulating osmoprotectants and antioxidants. J Plant Growth Regul. 2014;33:408–419. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Z, Peng Y, Huang B. Alteration of transcripts of stress-protective genes and transcriptional factors by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) associated with improved heat and drought tolerance in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1623. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li Z, Cheng B, Zeng W, Liu Z, Peng Y. The transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation in perennial creeping bentgrass in response to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and heat stress. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;162:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu T, Liu Z, Li Z, Peng Y, Zhang X, Ma X, Huang L, Liu W, Nie G, He L. Regulation of heat shock factor pathways by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) associated with thermotolerance of creeping bentgrass. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4713. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Priya M, Sharma L, Kaur R, Bindumadhava H, Nair RM, Siddique KHM, Nayyar H. GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid), as a thermo-protectant, to improve the reproductive function of heat-stressed mungbean plants. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thompson JF, Stewart CR, Morris CJ. Changes in amino acid content of excised leaves during incubation I. The effect of water content of leaves and atmospheric oxygen level. Plant Physiol. 1966;41:1578–1584. doi: 10.1104/pp.41.10.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Raggi V. Changes in free amino acids and osmotic adjustment in leaves of water-stressed bean. Physiol Plant. 1994;91:427–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1994.tb02970.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Serraj R, Shelp BJ, Sinclair TR. Accumulation of γ-aminobutyric acid in nodulated soybean in response to drought stress. Physiol Plant. 1998;102:79–86. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1998.1020111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bor M, Seckin B, Ozgur R, YiLmaz O, Ozdemir F, Turkan I. Comparative effects of drought, salt, heavy metal and heat stresses on gamma-aminobutyric acid levels of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Acta Physiol Plant. 2009;31:655–659. doi: 10.1007/s11738-008-0255-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pal S, Zhao J, Khan A, Yadav NS, Batushansky A, Barak S, Rewald B, Fait A, Lazarovitch N, Rachmilevitch S. Paclobutrazol induces tolerance in tomato to deficit irrigation through diversified effects on plant morphology, physiology and metabolism. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):39321. doi: 10.1038/srep39321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Filho EGA, Braga LN, Silva LMA, Miranda FR, Silva EO, Canuto KM, Miranda MR, de Brito ES, Zocolo GJ. Physiological changes for drought resistance in different species of Phyllanthus. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li Z, Huang T, Tang M, Cheng B, Peng Y, Zhang X. iTRAQ-based proteomics reveals key role of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in regulating drought tolerance in perennial creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;145:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mekonnen DW, Flugge UI, Ludewig F. Gamma-aminobutyric acid depletion affects stomata closure and drought tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 2016;245:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yong B, Xie H, Li Z, Li YP, Zhang Y, Nie G, Zhang XQ, Ma X, Huang LK, Yan YH, et al. Exogenous application of GABA improves PEG-induced drought tolerance positively associated with GABA-shunt, polyamines, and proline metabolism in white clover. Front Physiol. 2017;8:1107. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rezaei-Chiyaneh E, Seyyedi SM, Ebrahimian E, Moghaddam SS, Damalas CA. Exogenous application of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) alleviates the effect of water deficit stress in black cumin (Nigella sativa L.). Ind Crops Prod. 2018;112:741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.12.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Templer SE, Ammon A, Pscheidt D, Ciobotea O, Schuy C, McCollum C, Sonnewald U, Hanemann A, Forster J, Ordon F, et al. Metabolite profiling of barley flag leaves under drought and combined heat and drought stress reveals metabolic QTLs for metabolites associated with antioxidant defense. J Exp Bot. 2017;68:1697–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cairns JE, Sonder K, Zaidi PH, Verhulst N. Maize production in a changing climate-chapter one: impacts adaptation and mitigation strategies. Adv Agron. 2012;114:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jackson MB, Colmer TD. Response and adaptation by plants to flooding stress. Ann Bot. 2005;96:501–505. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shabala S. Physiological and cellular aspects of phyto-toxicity tolerance in plants: the role of membrane transporters and implications for crop breeding for waterlogging tolerance. New Phytol. 2011;190:289–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Irfan M, Hayat S, Hayat Q, Afroz S, Ahmad A. Physiological and biochemical changes in plants under waterlogging. Protoplasma. 2010;241:3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Puyang X, An M, Xu L, Han L, Zhang X. Antioxidant responses to waterlogging stress and subsequent recovery in two kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis, l.) cultivars. Acta Physiol Plant. 2015;37:197. doi: 10.1007/s11738-015-1955-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Abiko T, Kotula L, Shiono K, Malik AI, Colmer TD. Enhanced formation of aerenchyma and induction of a barrier to radial oxygen loss in adventitious roots of Zea nicaraguensis contribute to its waterlogging tolerance as compared with maize (Zea mays ssp. mays). Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:1618–1630. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Luan H, Shen H, Pan Y, Guo B, Lv C, Xu R. Elucidating the hypoxic stress response in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) during waterlogging: a proteomics approach. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9655. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27726-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Souza SC, Mazzafera P, Sodek L. Flooding of the root system in soybean: biochemical and molecular aspects of N metabolism in the nodule during stress and recovery. Amino Acids. 2016;48(5):1285–1295. doi: 10.1007/s00726-016-2179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ruperti B, Botton A, Populin F, Eccher G, Brilli M, Quaggiotti S, Trevisan S, Cainelli N, Guarracino P, Schievano E, et al. Flooding responses on grapevine: a physiological, transcriptional, and metabolic perspective. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:339. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Salah A, Zhan M, Cao C, Han Y, Ling L, Liu Z, Li P, Ye M, Jiang Y. γ-Aminobutyric acid promotes chloroplast ultrastructure, antioxidant capacity, and growth of waterlogged maize seedlings. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):484. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36334-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Streeter JG, Thompson JF. Anaerobic accumulation of γ-aminobutyric acid and alanine in radish leaves (Raphanus sativus L.). Plant Physiol. 1972;49:572–578. doi: 10.1104/pp.49.4.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fan TWM, Higashi RM, Frenkiel TA, Lane AN. Anaerobic nitrate and ammonium metabolism in flood-tolerant rice coleoptiles. J Exp Bot. 1997;48:1655–1666. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reggiani R, Nebuloni M, Mattana M, Brambilla I. Anaerobic accumulation of amino acids in rice roots: role of the glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthase cycle. Amino Acids. 2000;18:207–217. doi: 10.1007/s007260050018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brikis CJ, Zarei A, Chiu GZ, Deyman KL, Liu J, Trobacher CP, Hoover GJ, Subedi S, DeEll JR, Bozzo GG, et al. Targeted quantitative profiling of metabolites and gene transcripts associated with 4-aminobutyrate (GABA) in apple fruit stored under multiple abiotic stresses. Hortic Res. 2018;5(1):61. doi: 10.1038/s41438-018-0069-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang R, Guo Q, Gu Z. GABA shunt and polyamine degradation pathway on γ-aminobutyric acid accumulation in germinating fava bean (Vicia faba L.) under hypoxia. Food Chem. 2013;136(1):152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yang R, Guo Y, Wang S, Gu Z. Ca2+ and aminoguanidine on γ-aminobutyric acid accumulation in germinating soybean under hypoxia-NaCl stress. J Food Drug Anal. 2015;23(2):287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ding J, Yang T, Feng H, Dong M, Slavin M, Xiong S, Zhao S. Enhancing contents of γaminobutyric acid (GABA) and other micronutrients in dehulled rice during germination under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:1094–1102. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang P, Liu K, Gu Z, Yang R. Enhanced γ-aminobutyric acid accumulation, alleviated componential deterioration and technofunctionality loss of germinated wheat by hypoxia stress. Food Chem. 2018;269:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liao J, Wu X, Xing Z, Li Q, Duan Y, Fang W, Zhu X. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) accumulation in tea (Camellia sinensis L.) through the GABA shunt and polyamine degradation pathways under anoxia. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65:3013–3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Miyashita Y, Good AG. Contribution of the GABA shunt to hypoxia-induced alanine accumulation in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Munns R, Tester M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:651–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hasegawa PM, Bressan RA, Zhu J-K, Bohnert HJ. Plant cellular and molecular responses to high salinity. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2000;51:463–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gong Z, Xiong L, Shi H, Yang S, Herrera-Estrella LR, Xu G, Chao DY, Li J, Wang PY, Qin F, et al. Plant abiotic stress response and nutrient use efficiency. Sci China Life Sci. 2020; 63:635-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Renault H, Roussel V, El Amrani A, Arzel M, Renault D, Bouchereau A, Deleu C. The Arabidopsis pop2-1 mutant reveals the involvement of GABA transaminase in salt stress tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Renault H, El Amrani A, Berger A, Mouille G, Soubigou-Taconnat L, Bouchereau A, Deleu C. γ-Aminobutyric acid transaminase deficiency impairs central carbon metabolism and leads to cell wall defects during salt stress in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;36:1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Su N, Wu Q, Chen J, Shabala L, Mithofer A, Wang H, Qu M, Yu M, Cui J, Shabala S. GABA operates upstream of H+-ATPase and improves salinity tolerance in Arabidopsis by enabling cytosolic K+ retention and Na+ exclusion. J Exp Bot. 2019;70(21):6349–6361. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Akcay N, Bor M, Karabudak T, Ozdemir F, Turkan I. Contribution of Gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) to salt stress responses of Nicotiana sylvestris CMSII mutant and wild type plants. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169:452–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang J, Zhang Y, Du Y, Chen S, Tang H. Dynamic metabonomic responses of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants to salt stress. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(4):1904–1914. doi: 10.1021/pr101140n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Al-Quraan NA, Sartawe FA, Qaryouti MM. Characterization of γ-aminobutyric acid metabolism and oxidative damage in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings under salt and osmotic stress. J Plant Physiol. 2013;170:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ji J, Shi Z, Xie T, Zhang X, Chen W, Du C, Sun J, Yue J, Zhao X, Jiang Z, et al. Responses of GABA shunt coupled with carbon and nitrogen metabolism in poplar under NaCl and CdCl2 stresses. Ecotox Environ Saf. 2020;193:110322. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Che-Othman MH, Jacoby RP, Millar AH, Taylor NL. Wheat mitochondrial respiration shifts from the tricarboxylic acid cycle to the GABA shunt under salt stress. New Phytol. 2020;225(3):1166–1180. doi: 10.1111/nph.15713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang Y, Gu W, Meng Y, Xie T, Li L, Li J, Wei S. γ-Aminobutyric acid imparts partial protection from salt stress injury to maize seedlings by improving photosynthesis and upregulating osmoprotectants and antioxidants. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43609. doi: 10.1038/srep43609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cheng B, Li Z, Liang L, Cao Y, Zeng W, Zhang X, Ma X, Huang L, Nie G, Liu W, et al. The γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) alleviates salt stress damage during seeds germination of white clover associated with Na+/K+ transportation, dehydrins accumulation, and stress-related genes expression in white clover. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2520. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jin X, Liu T, Xu J, Gao Z, Hu X. Exogenous GABA enhances muskmelon tolerance to salinity-alkalinity stress by regulating redox balance and chlorophyll biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:48. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1660-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ma Y, Wang P, Wang M, Sun M, Gu Z, Yang R. GABA mediates phenolic compounds accumulation and the antioxidant system enhancement in germinated hulless barley under NaCl stress. Food Chem. 2019;270:593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wu X, Jia Q, Ji S, Gong B, Li J, Lu G, Gao H. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) alleviates salt damage in tomato by modulating Na(+) uptake, the GAD gene, amino acid synthesis and reactive oxygen species metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Carillo P. GABA Shunt in Durum Wheat. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:100. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shi S-Q, Shi Z, Jiang Z-P, Qi L-W, Sun X-M, Li C-X, Liu J-F, Xiao W-F, Zhang S-G. Effects of exogenous GABA on gene expression of Caragana intermedia roots under NaCl stress: regulatory roles for H2O2 and ethylene production. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:149–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ji J, Yue J, Xie T, Chen W, Du C, Chang E, Chen L, Jiang Z, Shi S. Roles of γ‑aminobutyric acid on salinity-responsive genes at transcriptomic level in poplar: involving in abscisic acid and ethylene-signalling pathways. Plant. 2018;248(3):675–690. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-2915-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gonzales CI, Maine MA, Cazanave J, Hadad HR, Benavides MP. Ni accumulation and its effects on physiological and biochemical parameters of Eichhornia crassipes. Environ Exp Bot. 2015;117:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Dubey S, Misra P, Dwivedi S, Chatterjee S, Bag SK, Mantri S, Asif MH, Rai A, Kumar S, Shri M, et al. Transcriptomic and metabolomic shifts in rice roots in response to Cr (VI) stress. BMC Genom. 2010;11:648. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kang SM, Radhakrishnan R, You YH, Khan AL, Lee KE, Lee JD, Lee IJ, Papen H. Enterobacter asburiae KE17 association regulates physiological changes and mitigates the toxic effects of heavy metals in soybean. Plant Biol. 2015;17:1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Daş ZA, Dimlioğlu G, Bor M, Özdemir F. Zinc induced activation of GABA-shunt in tobacco (Nicotiana tabaccum L.). Environ Exp Bot. 2016;122:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kumar N, Dubey AK, Upadhyay AK, Gautam A, Ranjan R, Srikishna S, Sahu N, Behera SK, Mallick S. GABA accretion reduces Lsi-1 and Lsi-2 gene expressions and modulates physiological responses in Oryza sativa to provide tolerance towards arsenic. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8786. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09428-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yang L, Yao J, Sun J, Shi L, Chen Y, Sun J. The Ca2+ signaling, Glu, and GABA responds to Cd stress in duckweed. Aquat Toxicol. 2020;218:105352. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2019.105352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cheng D, Tan M, Yu H, Li L, Zhu D, Chen Y, Jiang M. Comparative analysis of Cd-responsive maize and rice transcriptomes highlights Cd co-modulated orthologs. BMC Genom. 2018;19(1):709. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5109-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bouche N, Fait A, Bouchez D, Moller SG, Fromm H. Mitochondrial succinic-semialdehyde dehydrogenase of the γ-aminobutyrate shunt is required to restrict levels of reactive oxygen intermediates in plants. Pro Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6843–6848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fait A, Yellin A, Fromm H. GABA shunt deficiencies and accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates: insight from Arabidopsis mutants. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(2):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ludewig F, Huser A, Fromm H, Beauclair L, Bouche N. Mutants of GABA transaminase (POP2) suppress the severe phenotype of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (ssadh) mutants in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bao H, Chen X, Lv S, Jiang P, Feng J, Fan P, Nie L, Li Y. Virus-induced gene silencing reveals control of reactive oxygen species accumulation and salt tolerance in tomato by γ-aminobutyric acid metabolic pathway. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38:600–613. doi: 10.1111/pce.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Tarkowski LP, Signorelli S, Hofte M. γ-Aminobutyric acid and related amino acids in plant immune responses: emerging mechanisms of action. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43(5):1103–1116. doi: 10.1111/pce.13734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Takahashi H, Matsumura H, Kawai-Yamada M, Uchimiya H. The cell death factor, cell wall elicitor of rice blast fungus (Magnaporthe grisea) causes metabolic alterations including GABA shunt in rice cultured cells. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3(11):945–953. doi: 10.4161/psb.6112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sidhu OP, Annarao S, Pathre U, Snehi SK, Raj SK, Roy R, Tuli R, Khetrapal CL. Metabolic and histopathological alterations of Jatropha mosaic begomovirus-infected Jatropha curcas L. by HR-MAS NMR spectroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging. Plant. 2010;232(1):85–93. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Seifi HS, Curvers K, De Vleesschauwer D, Delaere I, Aziz A, Hofte M. Concurrent overactivation of the cytosolic glutamine synthetase and the GABA shunt in the ABA-deficient sitiens mutant of tomato leads to resistance against Botrytis cinerea. New Phytol. 2013;199(2):490–504. doi: 10.1111/nph.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Dimlioglu G, Das ZA, Bor M, Ozdemir F, Turkan I. The impact of GABA in harpin-elicited biotic stress responses in Nicotiana tabaccum. J Plant Physiol. 2015;188:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kogovsek P, Pompe-Novak M, Petek M, Fragner L, Weckwerth W, Gruden K. Primary metabolism, phenylpropanoids and antioxidant pathways are regulated in potato as a response to Potato virus Y infection. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.O’Leary BM, Neale HC, Geilfus CM, Jackson RW, Arnold DL, Preston GM. Early changes in apoplast composition associated with defence and disease in interactions between Phaseolus vulgaris and the halo blight pathogen Pseudomonas syringae Pv. phaseolicola. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39(10):2172–2184. doi: 10.1111/pce.12770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Chen F, Liu C, Zhang J, Lei H, Li HP, Liao YC, Tang H. Combined metabonomic and quantitative RT-PCR analyses revealed metabolic reprogramming associated with Fusarium graminearum resistance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:2177. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zaini PA, Nascimento R, Gouran H, Cantu D, Chakraborty S, Phu M, Goulart LR, Dandekar AM. Molecular profiling of Pierce’s disease outlines the response circuitry of Vitis vinifera to Xylella fastidiosa infection. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Tarkowski ŁP, Van de Poel B, Höfte M, Van den Ende W. Sweet immunity: inulin boosts resistance of lettuce (Lactuca sativa) against grey mold (Botrytis cinerea) in an ethylene-dependent manner. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1052. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Nehela Y, Killiny N. ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ and its vector, Diaphorina citri, augment the tricarboxylic acid cycle of their host via the γ-aminobutyric acid shunt and polyamines pathway. Mol Plant Micr Interact. 2019;32(4):413–427. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-18-0238-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Wang Q, Chen D, Wu M, Zhu J, Jiang C, Xu JR, Liu H. MFS transporters and GABA metabolism are involved in the self-defense against DON in Fusarium graminearum. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:438. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wang G, Kong J, Cui D, Zhao H, Niu Y, Xu M, Jiang G, Zhao Y, Wang W. Resistance against Ralstonia solanacearum in tomato depends on the methionine cycle and the γ‐aminobutyric acid metabolic pathway. Plant J. 2019;97:1032–1047. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Salvatore MM, Felix C, Lima F, Ferreira V, Duarte AS, Salvatore F, Alves A, Esteves AC, Andolfi A. Effect of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) on the metabolome of two strains of Lasiodiplodia theobromae isolated from grapevine. Molecule. 2020;25(17). doi: 10.3390/molecules25173833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Yang J, Sun C, Zhang Y, Fu D, Zheng X, Yu T. Induced resistance in tomato fruit by γ-aminobutyric acid for the control of alternaria rot caused by Alternaria alternata. Food Chem. 2017;221:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Bown AW, Macgregor KB, Shelp BJ. Gamma-aminobutyrate: defense against invertebrate pests? Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:424–427. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Huang T, Jander G, Vos MD. Non-protein amino acids in plant defense against insect herbivores: representative cases and opportunities for further functional analysis. Phytochem. 2011;72(13):1531–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Mithöfer A, Boland W. Plant defense against herbivores: chemical aspects. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:431–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Scholz SS, Reichelt M, Mekonnen DW, Ludewig F, Mithofer A. Insect herbivory-elicited GABA accumulation in plants is a wound-induced, direct, systemic, and jasmonate-independent defense response. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:1128. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]