Abstract

Background

Achieving a high response rate for physicians has been challenging, and with response rates declining in recent years, innovative methods are needed to increase rates. An emerging concept in survey methodology has been web-push survey delivery. With this delivery method, contact is made by mail to request a response by web. This study explored the feasibility of a web-push survey on a national sample of physicians.

Methods

A total of 1,000 physicians across six specialties were randomly assigned to a mail-only or web-push survey delivery. Each mode consisted of four contacts including an initial mailing, reminder postcard, and two additional follow-ups. Response rates were calculated using the American Association for Public Opinion Research’s response rate 3 calculation. Data collection occurred between Febuary and April 2018; data were analyzed March 2019.

Results

Overall reponse rates for the mail-only versus web-push survey delivery were comparable (51.2% vs. 52.8%). Higher response rates across all demographics were seen in the web-push delivery, with the exception of pulmonary/critical care and physicians over the age of 65. The web-push survey yielded a greater response after the first mailing, requiring fewer follow-up contacts resulting in a more cost-effective delivery.

Conclusions

A web-push mail survey is effective in achieving a comparable response rate to traditional mail-only delivery for physicians. The web-push survey was more efficient in terms of cost and in receiving responses in a more timely manner. Future research should explore the efficiency of a web-push survey delivery across various health care provider populations.

Keywords: survey methodology, response rates, physician survey, web-push delivery

Introduction

Physician surveys are an important tool in obtaining information on healthcare-related attitudes, beliefs, and practices (McLeod et al. 2013), but achieving a high response rate for this population is challenging (Cho, Johnson, and VanGeest 2013; Thorpe et al. 2009; VanGeest, Johnson, and Welch 2007). Given the potential for low response rates in this population (Asch, Jedrziewski, and Christakis 1997; Cummings, Savitz, and Konrad 2001), understanding research strategies that facilitate adequate response rates in physician surveys is critical to strengthen generalizability and to reduce bias. A recent review has found that incentives, repeated follow-up, and data collection mode are important factors related to response rates in general as well as for this target population (Dillman 2015; Dillman, Smyth, and Christian 2014; Field et al. 2002).

The application of Dillman’s Tailored Design Method has been successful in achieving a high response rate (range 56%–86%) from healthcare providers on a variety of health topics (Abatemarco, Steinberg, and Delnevo 2007; Delnevo, Abatemarco, and Steinberg 2004; Ferrante et al. 2008; 2009; Steinberg et al. 2011). More recently, other strategies have been explored for healthcare provider surveys to combat declining response rates including web-based and mixed mode surveys (Millar and Dillman 2011). Web-based survey delivery to physicians offers immediate survey delivery, real time data, and inexpensive costs (Cunningham et al. 2015). Despite these advantages, studies have shown that physician response rates of web-only surveys are lower than mail surveys (Dillman 2015; Lusk et al. 2007). In mixed-mode survey methods, one mode of response is initially offered followed by an alternate mode in a follow-up contact (Millar and Dillman 2011). While mixed-mode surveys have been shown to facilitate response rates (Beebe et al. 2007), challenges remain in adapting this method to the physician population. Indeed, mail surveys tend to have higher responses rates for the physician population compared with online or mixed-mode surveys (Cho, Johnson, and VanGeest 2013). Furthermore, alternate modes of data collection, such as online, are problematic given there is no comprehensive list of physician emails to function as a sampling frame (Braithwaite et al. 2003), and while e-mail addresses are available in the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, they are not included for all physicians and may be inaccurate (Klabunde et al. 2012). Until there are comprehensive sampling frames of physician email addresses, mail delivery will remain a dominant sampling approach.

Recent work in survey methodology has explored web-push mail surveys, which may yield higher response rates than paper-only survey delivery (McMaster et al. 2017). In web-push surveys the initial correspondence contains a postal request to respond by web. Follow-up mailings include a reminder letter to complete the survey online followed by a paper questionnaire. Offering a paper survey after the initial web request has been shown to increase response rates. The extent to which this method could work for physician surveys is unknown— as such, this split sample experiment aims to look at differences in response rates between mail-only delivery and a web-push delivery in a sample of physicians.

Methods

This survey experiment was embedded in a larger national, repeated cross-sectional mail survey of physicians focused on attitudes and beliefs regarding tobacco use, smoking cessation and electronic cigarettes (Singh et al. 2017; Steinberg, Giovenco, and Delnevo 2015). In brief, the sampling frame for the national study was compiled from the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile, via the vendor Medical Marketing Service; 3,000 board-certified practicing physicians, equally distributed across six specialties: family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics/gynecology (ob/gyn), cardiology, pulmonary/critical care, and hematology/oncology, were randomly selected. From the national sample, we then randomly selected 1,000 physicians and then randomly assigned them to one of two survey mode conditions: traditional mail or web-push survey. Data collection occurred between Febuary and April 2018; data were analyzed March 2019.

The first mailing contained an introductory cover letter, which differed by mode condition, and a $25 Starbucks® gift card; for those assigned to the mail survey mode, they also received a paper copy of the survey, while those assigned to the web-push mode were given instructions on how to complete the web survey in the cover letter (i.e., the survey URL was provided with an anonymous login code). One week after the first mailing, we made a second mailing contact via postcard reminders to nonrespondents; the web-push mode postcard contained the survey URL and login code. The third mailing to nonresponders mirrored the first contact, minus the gift card. The fourth mailing to all nonresponders was a mixed mode and included a paper survey as well as a cover letter with instructions on how to complete the web survey. As such, nonresponders in either condition were able to choose their survey mode (i.e., a web-push nonrespondent could submit a paper survey and a mail-survey mode nonrespondent could now do the survey online).

Overall response rates were calculated using the American Association for Public Opinion Research’s response rate 3 calculation (Smith 2009), which estimates the proportion of cases of unknown eligibility that are eligible using data gathered during fielding. For example, if a survey had 100 completes and 50 ineligibles, the eligibility rate among nonresponders is assumed to be 66% (i.e., 100 divided by 150). We examined responses rates by mode condition after each physician contact as well as final response rates by demographics.

Results

Overall, 362 physicians responded to the survey and were equally distributed across the two survey modes. A total of 158 cases were determined to be ineligible (i.e., death, retirement, no active medical license in state, not board certified, not providing outpatient care). More ineligible cases were identified in the web-push condition (83 vs. 75). Of note, the first question on the survey screened for eligibility (i.e., providing outpatient care) and for the web-push condition, the survey terminated with a “no” response, whereas for the traditional paper survey, the participant would need to indicate “no” and mail the survey back. The small differences for “ineligibles” produces slightly different overall response rates, despite the same number of completes for each group.

As shown in Table 1, response rates did not significantly differ for the two data collection modes overall or within demographic subgroups, with both modes achieving a response rate just over 50%. Females had slightly higher response rates in both modes compared with males, but the web-push condition performed slightly better. Differences in response rate are noted across speciality groups, with the highest response rates among family and internal medicine and the lowest among cardiology. Slightly higher responses rates for the web-push condition were noted for family medicine and oncology, whereas slightly higher response rates were noted for the traditional mail survey condition for ob/gyns. Response rates overall were highest for those under the age of 45 and declined by age for the web-push mode. The traditional mail survey mode performed slightly better for those 65 years of age or older.

Table 1:

Final response rates by demographics for paper versus web-push mode

| Paper | Web-push | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 53.80% | 59.50% |

| Male | 49.80% | 49.40% |

| Specialty | ||

| Cardiology | 37.80% | 41.60% |

| Family Medicine | 56.20% | 65.20% |

| Internal Medicine | 64.80% | 65.40% |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 56.20% | 49.40% |

| Oncology | 40.20% | 45.80% |

| Pulmonary/Critical Care | 51.20% | 47.40% |

| Age Group | ||

| under 45 | 57.90% | 58.60% |

| 45–54 | 45.50% | 52.30% |

| 55–64 | 47.00% | 50.00% |

| 65+ | 56.30% | 48.90% |

| Overall | 51.20% | 52.80% |

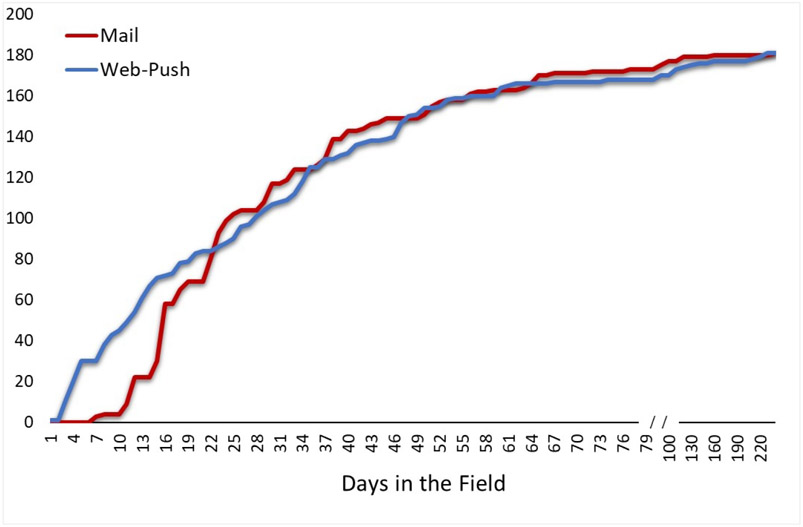

Figure 1 depicts cumulative survey completion for the two data collection modes. Differences between the two modes are noted within the first three weeks of fielding, such that the web-push yielded greater completions than the mail survey, after which the mail survey conditions catches up and keeps pace with the web-push condition. While, ultimately, the two yielded nearly identical response rates, the shorter response time for the web-push condition yielded efficiencies, such that there were fewer follow-up contacts in the web-push condition. Indeed, a total of 1,714 mailings were prepared for the web-push condition versus 1,781 for the traditional mail survey. In addition, as noted previously, we were able to identify a greater number of ineligible respondents in the web-push condition.

Figure 1:

Cumulative Completed Surveys Over Time by Survey Mode Condidion

When looking at an economic evaluation comparing the costs involved for each mode (Table 2), we found that the total cost for the traditional mail survey was 25% higher than web-push. The main sources of savings included printing costs of the paper survey, postage, and labor costs associated with assembling the mailings and data entry. With the number of completes being equal between the two modes, this resulted in a cost per complete of $31.70 for the mail survey compared with $23.80 for the web-push.

Table 2:

Total cost of mailings for paper vs. web-push mode

| Paper | Web-push | |

|---|---|---|

| Item | ||

| Paper Survey Printing | $989.45 | $267.96 |

| Envelopes | $436.90 | $299.72 |

| Follow-up Postcard | $89.28 | $81.72 |

| Labels | $32.06 | $30.76 |

| Postage | $1,844.10 | $1,518.30 |

| Labor | $2,347.20 | $2,110.80 |

| Total | $5,738.99 | $4,309.26 |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the feasibility of a web-push approach for physician surveys. Overall, we found that the web-push data collection mode obtained about the same response rate as the traditional paper and pencil mail survey. Moreover, this was without notable differences by demographics with a few exceptions. Physicians 65 years of age or older and ob/gyns had lower response rates for the web-push condition compared with the mail-only condition. This is consistent with prior research which has found higher response rates among younger physicians for web-based surveys (Ferrante et al. 2009). In our study, we found higher response rates for females in both delivery modes, and this finding held within most specialties. Previous literature examining differences in physician response rates by gender for mail and web surveys have found mixed results. While some studies find no differences in survey response rate by gender (Kellerman and Herold 2001), others have noted higher survey response rates among male physicians (Braithwaite et al. 2003; Cunningham et al. 2015), while others have documented higher rates among female physicians (Cull et al. 2005; Delnevo, Abatemarco, and Steinberg 2004).

When comparing the response rates of both modes, we see that web-push, when combined with the Tailored Design Method, is capable of achieving a comparable response rate to mail-only delivery, with notable efficiencies. The shorter response time for the web-push delivery allowed for a more prompt response time and identification of ineligibles proceeding to fewer follow-ups. Additional costs for the mail-only delivery, including cost of printing the paper survey, postage for the return envelope, and time taken for data entry, resulted in the web-push delivery being more cost-effective. This finding is consistent with previous research which found web-based survey delivery to be more cost efficient among physicians (Scott et al. 2011).

Limitations to note include the small sample size for specific subgroups (e.g., females) which did not yield statistically significant differences, despite the fact that there were meaningful differences between the two survey modes for females and those 65 years of age or older. Likewise, caution should be considered when viewing the lower response rate for cardiologists. In our sample, males and those 65 years of age or older who overall had lower response rates were overrepresented in this speciality. As such, the lower response could be partially explained by these demographic differences.

Conclusions

With survey reponse rates among physicians continuing to decline, it is important to explore alternative delivery methods among this population. This study found that implementing a web-push delivery design was more cost-effective and resulted in comparable response rates than mail-only delivery. For these reasons, the remaining sample of 2,000 physicians for our national survey was fielded using web-push delivery, which achieved an overall response rate above 50%, a notable accomplishment in the context of the challenges with physician surveys. Further research should continue exploring the effectiveness of web-push delivery on a variety of health topics and healthcare provider populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The study described was supported by grant number R01CA190444 from the National Institute of Health. The content does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Abatemarco Diane J., Steinberg Michael B., and Delnevo Cristine D.. 2007. “Midwives’ Knowledge, Perceptions, Beliefs, and Practice Supports Regarding Tobacco Dependence Treatment.” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 52 (5): 451–57. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch David A., Kathryn Jedrziewski M, and Christakis Nicholas A.. 1997. “Response Rates to Mail Surveys Published in Medical Journals.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 50 (10): 1129–36. 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe Timothy J., Richard Locke G III, Barnes Sunni A., Davern Michael E., and Anderson Kari J.. 2007. “Mixing Web and Mail Methods in a Survey of Physicians.” Health Services Research 42 (3p1): 1219–34. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite Dejana, Emery Jon, de Lusignan Simon, and Sutton Stephen. 2003. “Using the Internet to Conduct Surveys of Health Professionals: A Valid Alternative?” Family Practice 20 (5): 545–51. 10.1093/fampra/cmg509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Young Ik, Johnson Timothy P., and VanGeest Jonathan B.. 2013. “Enhancing Surveys of Health Care Professionals: A Meta-Analysis of Techniques to Improve Response.” Evaluation & the Health Professions 36 (3): 382–407. 10.1177/0163278713496425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull William L., O’Connor Karen G., Sharp Sanford, and Tang Suk-fong S.. 2005. “Response Rates and Response Bias for 50 Surveys of Pediatricians.” Health Services Research 40 (1): 213–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings Simone M., Savitz Lucy A., and Konrad Thomas R.. 2001. “Reported Response Rates to Mailed Physician Questionnaires.” Health Services Research 35 (6): 1347. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham Ceara Tess, Quan Hude, Hemmelgarn Brenda, Noseworthy Tom, Beck Cynthia A., Dixon Elijah, Samuel Susan, Ghali William A., Sykes Lindsay L., and Jetté Nathalie. 2015. “Exploring Physician Specialist Response Rates to Web-Based Surveys.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 15 (1): 32 10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delnevo Cristine D., Abatemarco Diane J., and Steinberg Michael B.. 2004. “Physician Response Rates to a Mail Survey by Specialty and Timing of Incentive.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 26 (3): 234–36. 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman Don A. 2015. Climbing Stairs Many Steps at a Time: The New Normal in Survey Methodology. PowerPoint presentation; Presented September 18, 2015. http://ses.wsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/DILLMAN-talk-Sept-18-2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman Don A., Smyth Jolene D., and Christian Leah Melani. 2014. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante Jeanne M., Piasecki Alicja K., Ohman-Strickland Pamela A., and Crabtree Benjamin F.. 2009. “Family Physicians’ Practices and Attitudes Regarding Care of Extremely Obese Patients.” Obesity 17 (9): 1710–16. 10.1038/oby.2009.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante Jeanne M., Winston Dock G., Chen Ping-Hsin, and de la Torre Andrew N.. 2008. “Family Physicians’ Knowledge and Screening of Chronic Hepatitis and Liver Cancer.” Family Medicine 40 (5): 345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field Terry S., Cadoret Cynthia A., Brown Martin L., Ford Marvella, Greene Sarah M., Hill Deanna, Hornbrook Mark C., Meenan Richard T., White Mary Jo, and Zapka Jane M.. 2002. “Surveying Physicians: Do Components of the “Total Design Approach" to Optimizing Survey Response Rates Apply to Physicians?” Medical Care 40 (7): 596–605. 10.1097/00005650-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman Scott E., and Herold Joan. 2001. “Physician Response to Surveys A Review of the Literature.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 20 (1): 61–67. 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klabunde Carrie N., Willis Gordon B., McLeod Caroline C., Dillman Don A., Johnson Timothy P., Greene Sarah M., and Brown Martin L.. 2012. “Improving the Quality of Surveys of Physicians and Medical Groups: A Research Agenda.” Evaluation & the Health Professions 35 (4): 477–506. 10.1177/0163278712458283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusk Christine, Delclos George L., Burau Keith, Drawhorn Derek D., and Aday Lu Ann. 2007. “Mail Versus Internet Surveys: Determinants of Method of Response Preferences among Health Professionals.” Evaluation & the Health Professions 30 (2): 186–201. 10.1177/0163278707300634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod Caroline C., Klabunde Carrie N., Willis Gordon B., and Stark Debra. 2013. “Health Care Provider Surveys in the United States, 2000–2010: A Review.” Evaluation & the Health Professions 36 (1): 106–26. 10.1177/0163278712474001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMaster Hope Seib, LeardMann Cynthia A., Speigle Steven, Dillman Don A., and Millennium Cohort Family Study Team. 2017. “An Experimental Comparison of Web-Push Vs. Paper-Only Survey Procedures for Conducting an In-Depth Health Survey of Military Spouses.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 17 (1): 73 10.1186/s12874-017-0337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar Morgan M., and Dillman Don A.. 2011. “Improving Response to Web and Mixed-Mode Surveys.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75 (2): 249–69. 10.1093/poq/nfr003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Anthony, Jeon Sung-Hee, Joyce Catherine M., Humphreys John S., Kalb Guyonne, Witt Julia, and Leahy Anne. 2011. “A Randomised Trial and Economic Evaluation of the Effect of Response Mode on Response Rate, Response Bias, and Item Non-Response in a Survey of Doctors.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (1): 126 10.1186/1471-2288-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Binu, Hrywna Mary, Wackowski Olivia A., Delnevo Cristine D., Jane Lewis M, and Steinberg Michael B.. 2017. “Knowledge, Recommendation, and Beliefs of e-Cigarettes among Physicians Involved in Tobacco Cessation: A Qualitative Study.” Preventive Medicine Reports 8 (December): 25–29. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Tom W. 2009. A Revised Review of Methods to Estimate the Status of Cases with Unknown Eligibility. Chicago: University of Chicago, National Opinion Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg Michael B., Giovenco Daniel P., and Delnevo Cristine D.. 2015. “Patient-Physician Communication Regarding Electronic Cigarettes.” Preventive Medicine Reports 2: 96–98. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg Michael B., Hanos Zimmermann M, Gundersen DA, Hart C, and Delnevo CD. 2011. “Physicians’ Perceptions Regarding Effectiveness of Tobacco Cessation Medications: Are They Aligned with the Evidence?” Preventive Medicine 53 (6): 433–34. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe C, Ryan B, McLean SL, Burt A, Stewart M, Brown JB, Reid GJ, and Harris S. 2009. “How to Obtain Excellent Response Rates When Surveying Physicians.” Family Practice 26 (1): 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanGeest Jonathan B., Johnson Timothy P., and Welch Verna L.. 2007. “Methodologies for Improving Response Rates in Surveys of Physicians: A Systematic Review.” Evaluation & the Health Professions 30 (4): 303–21. 10.1177/0163278707307899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]