Nitric oxide (NO), strigolactones (SLs) and karrikins (KARs) are bioactive signal molecules controlling root morphology. Our knowledge regarding the signal interplay of NO with SLs or KARs is limited. Our previous results pointed out that there is signal interplay between SL and S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR)-mediated NO/S-nitrosothiol (SNO) levels in Arabidopsis. In this addendum, we further prove that the pharmacological increment of SL levels by the application of rac-GR24 decreases GSNOR abundance, while reducing SL synthesis by TIS108 intensifies GSNOR protein level and possibly promotes NO signaling in Arabidopsis. Additionally, we observed that the endogenous NO level in the roots of htl-3 (KAR receptor) and d14 (SL receptor) mutants is significantly higher compared to the wild-type. These results, together with the previous ones, confirm the interplay of GSNOR-regulated NO/SNO signaling with SL- and KAR-dependent signal transduction in Arabidopsis.

SLs are recognized as terpenoid lactons consisting of triciyclic lacton (ABC ring) and butenolide group (D ring).1–4 SLs are synthesized from all-trans β-carotene by β-carotene isomerase DWARF 27 (D27) and two carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases CCD7 and CCD8.5 These enzymes produce carlactone (CL) in two subsequent steps from 9-cis-β-carotene. CL is a bioactive precursor of SLs which is oxidized by MORE AXILLARY GROWTH 1 (MAX1)5 yielding canonical and non-canonical SLs. The perception and signal transduction of SL is catalyzed by DWARF14 (D14) and MORE AXILLARY GROWTH 2 (MAX2), respectively.6 D14 is an α/β hydrolase hormone receptor, consisting of a conserved Ser-His-Asp triad.7 D14 binds the hormone and after that cleaves the enol ether bound between the ABC and D rings. The second component of the SL response pathway is MAX2, a member of the F-BOX protein family. MAX2 contains leucine-rich repeats and it is the part of SCF-type ubiquitin ligase complex.8 Karrikins are important smoke components which stimulate seed germination after fire.9 KARs are produced by combusting carbohydrates, for example, cellulose in the plant. Interestingly, KARs and SLs share common response pathway element MAX2; furthermore, they have similar structure (butenolide group). KARRIKIN-INSENSITIVE2 (KAI2) is required for the perception of KARs.10,11 Both SLs and KARs represent new classes of phytohormones, and regulate shoot branching, secondary growth, leaf senescence and control many aspects of root development like primary root length, adventitious root initiation, lateral root formation and root hair growth.8,12–16

The above root growth parameters are regulated also by nitric oxide (NO) signal molecule. NO is a hydrophobic, small diatomic gaseous molecule which has various effects on plant physiology and development including stomatal closure, stimulating primary root length, promoting lateral root formation and triggering biotic and abiotic stress responses.17,18 As a free radical, NO can rapidly react with reactive oxygen species and can modify proteins. One of the most important signaling pathway is S-nitrosation. In this process, NO reacts with cysteine residue of glutathione and forms S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO). GSNO is a stable molecule; it can be transported via xylem; therefore, it is a mobile reservoir of NO signal.19 GSNO is enzymatically degraded by a GSNO reductase (GSNOR) which is a highly conserved cysteine-rich homodimer enzyme, and contains two catalytic zinc ions in each subunit.20 Our previous results indicated that SL deficiency in max1-1 and max2-1 seedlings caused elevated NO/S-nitrosothiol (SNO) levels due to decreased abundance and activity of GSNOR enzyme.21 Since GSNOR is the key enzyme regulating NO-related signal transduction, we further examined the putative SL-induced alterations in its level.

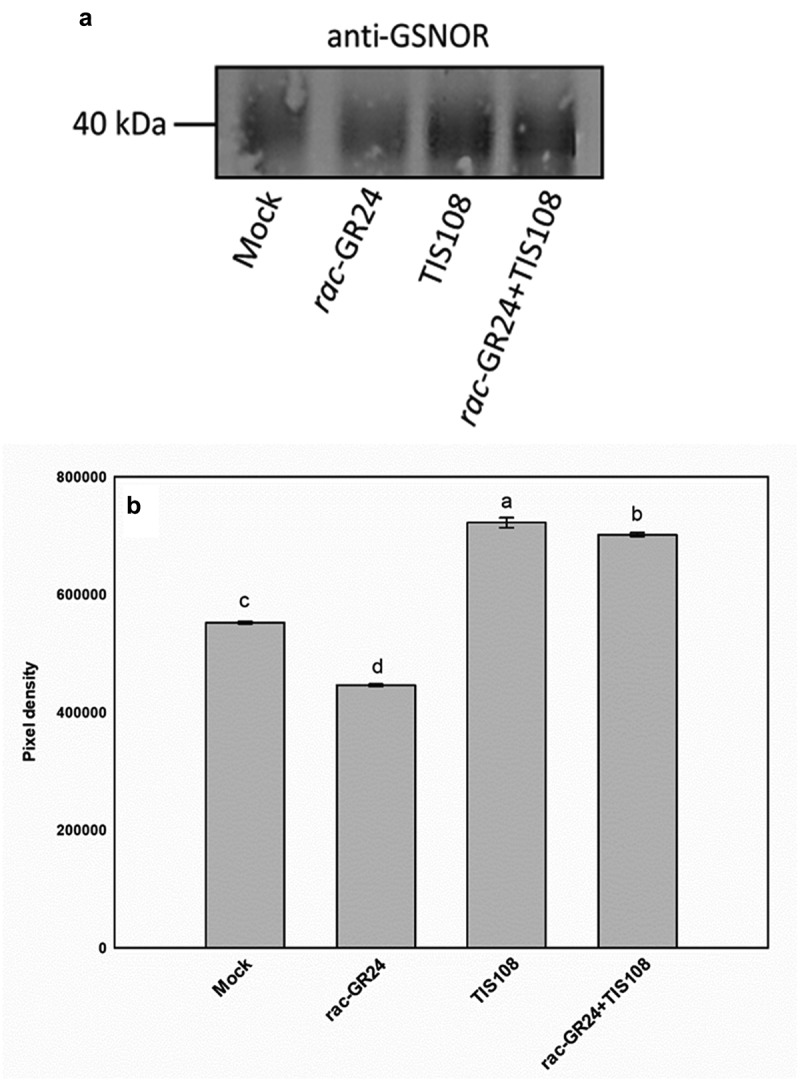

We applied SL mimic rac-GR24 (2 µM) and the inhibitor of SL synthesis TIS108 (5 µM) in order to modify SL level and signaling in wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana (Col-0). Four-d-old seedlings were exposed to the treatments and GSNOR protein abundance was analyzed in 7-d-old seedlings by Western blot according to Oláh et al.21 Compared to control, rac-GR24 resulted in reduced GSNOR protein abundance, but the application of SL inhibitor TIS108 increased the amount of GSNOR protein (Figure 1). When rac-GR24 and TIS108 were applied together, the level of GSNOR protein increased compared to untreated samples. These results seemingly contradict the previous results obtained using max1-1 and max2-1, which may be due to the fact that exogenous applications represent different conditions compared to untreated mutants. Another possible explanation may be that the effect of the MAX1 and MAX2 mutations on GSNOR is not SL-specific, but there is some indirect relationship between gene defect and GSNOR protein levels. Moreover, due to the poor detectability of SLs in plant tissues, the effect of rac-GR24 and/or TIS108 on endogenous SLs levels of the seedlings is not known. These methodological issues should be considered.

Figure 1.

(a) Abundance of GSNOR protein in 7-d-old Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings grown without (mock) or with rac-GR24 (2 µM), TIS108 (5 µM) or rac-GR24 plus TIS108. Relevant bands showing GSNOR signals were quantified by Gelquant software (provided by biochemlabsolutions.com) and the values of pixel densities are presented in panel B. Different letters indicate significant differences according to Duncan’s test (n = 3, P ≤ 0.05)

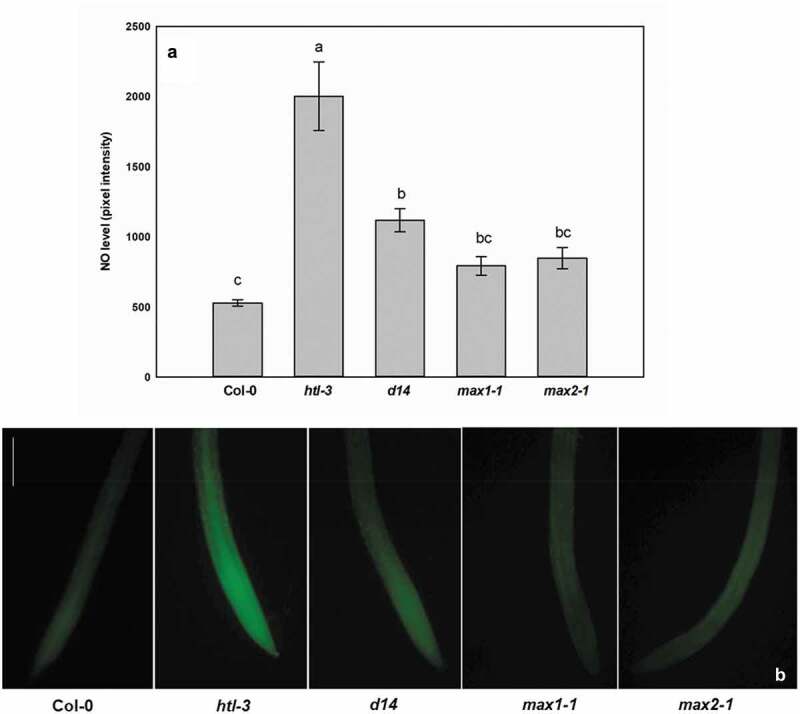

Since MAX2 mediates both SL and KAR signaling, max2-1 mutant alone is not sufficient to determine whether NO is associated with SL or KAR signals or with both of them in the root system. Therefore, the endogenous NO levels of KAR receptor (htl-3) and SL receptor (d14) mutants were compared with that of the wild-type max1-1 and max2-1. The detection of endogenous NO levels was performed according to Oláh et al.21 Interestingly, the htl-3 mutation resulted in ~four times higher NO levels in the root compared to the wild-type, and also the deficiency of D14 receptor led to elevated NO levels (Figure 2). In order to support the hypothesis that KAR and NO signal pathways interfere, we evaluated possible S-nitrosation of KAR-specific signal proteins KAI2 and SUPRESSOR OF MAX1 (SMAX1). Peptide sequences were extracted from UNIPROT (www.uniprot.org) and submitted to in silico prediction software GPS-SNO 1.0,22 freely available at http://sno.biocuckoo.org/, iSNO-PseAAC,23 freely available at http://app.aporc.org and DeepNitro,24 freely available at http://deepnitro.renlab.org. Interestingly, only one of the software tools (iSNO-PseAAC) predicted S-nitrosation of KAI2 protein, while in case of SMAX1, several cysteine (Cys) residues were predicted to be S-nitrosated by all three programs (Table 1). These suggest that these KAR-specific signal proteins may be modified/regulated by NO-dependent S-nitrosation; however, this hypothesis should be experimentally proved in the future.

Figure 2.

Level of nitric oxide (pixel intensity, (a)) and representative microscopic images taken from root tips labeled with DAF-FM DA (b) in 7-d-old wild type (Col-0), KAR receptor mutant (htl-3), SL receptor mutant (d14), SL biosynthesis mutant (max1-1) and SL/KAR signaling mutant (max2-1) Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings grown under stress-free conditions. Different letters indicate significant differences according to Duncan’s test (n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). Scale bar = 110.6 µm

Table 1.

In silico prediction of S-nitrosation of proteins involved in KAR perception and signaling using GSP-SNO 1.0, iSNO-PseAAC and DeepNitro software tools. Predictions were carried out using medium threshold. Amino acid positions and peptides predicted by more than one computational tools are in italic

| GPS-SNO 1.0 |

iSNO-PseAAC |

Deep-Nitro |

||||

| Protein name | Position | Peptide | Position | Peptide | Position | Peptide |

| KAR perception | ||||||

| KAI (A. thaliana) | 154 | EAIRSNYKAWCLGFAPLAVPP | ||||

| 209 | RQILPFVTVPCHILQSVKDLA | |||||

| KAR signaling | ||||||

| SMAX1 (A. thaliana) | 637 | VAATVSQCKLGNGKR | 115 | KRAQAHQRRGCPEQQQQPLLA | 115 | KRAQAHQRRGCPEQQQQPLLA |

| 962 | SSGTYGDCTVARLEL | 417 | SFVPANRTLKCCPQCLQSYER | 479 | QKKWNDACVRLHPSF | |

| 580 | GDVQVRDFLGCISSESVQNNN | 809 | KFGKRRASWLCSDEERLTKPK | |||

| 637 | AAAVAATVSQCKLGNGKRRGV | |||||

| 809 | KFGKRRASWLCSDEERLTKPK | |||||

| 865 | QGFSGKLSLQCVPFAFHDMVS | |||||

| 962 | RVSSSGTYGDCTVARLELDED | |||||

Collectively, these results further support the hypothesis regarding the crosstalk between NO, SL and KAR in regulating Arabidopsis root development. Further experiments should clarify the detailed effect of KAR on NO metabolism and signaling and vice versa.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (grant number NKFIH K 120383 and K 135303). Dóra Oláh is supported by the ÚNKP-20-3-SZTE-478 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund. Vilmos Soós is supported by NKFIH K 128644.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Emberi Eroforrások Minisztériuma [ÚNKP-20-3-SZTE-478]; National Research, Development and Innovation [128644]; National Research, Development and Innovation [120383]; National Research, Development and Innovation [135303].

References

- 1.Rani K, Zwanenburg B, Sugimoto Y, Yoneyama K, Bouwmeester HJ.. Biosynthetic considerations could assist the structure elucidation of host plant produced rhizosphere signalling compounds (strigolactones) for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and parasitic plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008;46(7):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zwanenburg B, Mwakaboko AS, Reizelman A, Anilkumar G, Sethumadhavan D.. Structure and function of natural and synthetic signalling molecules in parasitic weed germination. Pest Manage Sci. 2009;65(5):478–491. doi: 10.1002/ps.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie X, Yoneyama K, Yoneyama K.. The strigolactone story. Ann Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:93–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie X, Yoneyama K, Kisugi T, Uchida K, Ito S, Akiyama K, … Yoneyama K. Confirming stereochemical structures of strigolactones produced by rice and tobacco. Mol Plant. 2013;6(1):153–163. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alder A, Jamil M, Marzorati M, Bruno M, Vermathen M, Bigler P, … Al-Babili S. The path from β-carotene to carlactone, a strigolactone-like plant hormone. Science. 2012;335(6074):1348–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1218094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seto Y, Sado A, Asami K, Hanada A, Umehara M, Akiyama K, Yamaguchi S. Carlactone is an endogenous biosynthetic precursor for strigolactones. Proc National Acad Sci. 2014;111(4):1640–1645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314805111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruyter-Spira C, Al-Babili S, Van Der Krol S, Bouwmeester H. The biology of strigolactones. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18(2):72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamiaux C, Drummond RS, Janssen BJ, Ledger SE, Cooney JM, Newcomb RD, Snowden KC. DAD2 is an α/β hydrolase likely to be involved in the perception of the plant branching hormone, strigolactone. Curr Biol. 2012;22(21):2032–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Cuyper C, Struk S, Braem L, Gevaert K, De Jaeger G, Goormachtig S. Strigolactones, karrikins and beyond. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40(9):1691–1703. doi: 10.1111/pce.12996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flematti GR, Ghisalberti EL, Dixon KW, Trengove RD. A compound from smoke that promotes seed germination. Science. 2004;305(5686):977. doi: 10.1126/science.1099944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conn CE, Nelson DC. Evidence that KARRIKIN-INSENSITIVE2 (KAI2) receptors may perceive an unknown signal that is not karrikin or strigolactone. Front Plant Sci. 2016;6:1219. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez-Roldan V, Fermas S, Brewer PB, Puech-Pagès V, Dun EA, Pillot JP, Bouwmeester H. Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature. 2008;455(7210):189–194. doi: 10.1038/nature07271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agusti J, Herold S, Schwarz M, Sanchez P, Ljung K, Dun EA, … Greb T. Strigolactone signaling is required for auxin-dependent stimulation of secondary growth in plants. Proc National Acad Sci. 2011;108(50):20242–20247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111902108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapulnik Y, Delaux PM, Resnick N, Mayzlish-Gati E, Wininger S, Bhattacharya C, … Beeckman T. Strigolactones affect lateral root formation and root-hair elongation in Arabidopsis. Planta. 2011;233(1):209–216. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1310-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen A, Mason MG, De Cuyper C, Brewer PB, Herold S, Agusti J, … Beveridge CA. Strigolactones suppress adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis and pea. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(4):1976–1987. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.187104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamada Y, Furusawa S, Nagasaka S, Shimomura K, Yamaguchi S, Umehara M. Strigolactone signaling regulates rice leaf senescence in response to a phosphate deficiency. Planta. 2014;240(2):399–408. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon E, Feechan A, Yun BW, Hwang BH, Pallas JA, Kang JG, Loake GJ. AtGSNOR1 function is required for multiple developmental programs in Arabidopsis. Planta. 2012;236(3):887–900. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1697-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernández-Marcos M, Sanz L, Lewis DR, Muday GK, Lorenzo O. Nitric oxide causes root apical meristem defects and growth inhibition while reducing PIN-FORMED 1 (PIN1)-dependent acropetal auxin transport. Proc National Acad Sci. 2011;108(45):18506–18511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108644108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Begara-Morales JC, Chaki M, Valderrama R, Sánchez-Calvo B, Mata-Pérez C, Padilla MN, Barroso JB. NO buffering and conditional NO release in stress response. J Exp Bot. 2018;69:3425–3438. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindermayr C. Crosstalk between reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide in plants: key role of S-nitrosoglutathione reductase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;122:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oláh D, Feigl G, Molnár Á, Ördög A, Kolbert Z. Strigolactones interact with nitric oxide in regulating root system architecture of Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:1019. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue Y, Liu Z, Gao X, Jin C, Wen L, Yao X, Ren J, Bajic VB. GPS-SNO: computational prediction of protein S-nitrosylation sites with a modified GPS algorithm. PloS One. 2010;5(6):e11290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y, Ding J, Wu LY, Chou KC. iSNO-PseAAC: predict cysteine S-nitrosylation sites in proteins by incorporating position specific amino acid propensity into pseudo amino acid composition. PloS One. 2013;8(2):e55844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Y, Luo X, Li Y, Chen L, Ma W, Huang J, … Ren J. DeepNitro: prediction of protein nitration and nitrosylation sites by deep learning. Genomics Proteomics Bioinf. 2018;16(4):294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]