Abstract

Zebrafish is an emerging alternative model in behavioral and neurological studies for pharmaceutical applications. However, little is known regarding the effects of noise exposure on laboratory-grown zebrafish. Accordingly, this study commenced by exposing zebrafish embryos to loud background noise (≥200 Hz, 80 ± 10 dB) for five days in a microfluidic environment. The noise exposure was found to affect the larvae hatching rate, larvae length, and swimming performance. A microfluidic platform was then developed for the sorting/trapping of hatched zebrafish larvae using a non-invasive method based on light cues and acoustic actuation. The experimental results showed that the proposed method enabled zebrafish larvae to be transported and sorted into specific chambers of the microchannel network in the desired time frame. The proposed non-invasive trapping method thus has potentially profound applications in drug screening.

INTRODUCTION

The zebrafish model has attracted significant interest in biological and toxicology studies.1–3 Zebrafish has a well-developed hearing system and hence, like humans, excessive exposure to noise may seriously impact their early development.4 In laboratory settings, threats and/or uncertainties such as those encountered in natural outdoor environments are typically not present.5 However, the larvae are commonly exposed to background noise and ambient light conditions that are not encountered in nature. It has been suggested that such conditions may induce behavioral changes in the zebrafish larvae due to anxiety or curiosity. Furthermore, in the case of background noise, these changes may vary as a function of the sound level.6 In general, noise impact-related studies in indoor conditions provide the opportunity to manipulate the experimental parameters under carefully controlled conditions in order to investigate the effect of noise on the variable of interest (e.g., the replication rate of zebrafish in the present case). Previous studies on cultured zebrafish have revealed that sound exposure can cause temporary or permanent hearing loss.7 Furthermore, even moderate noise levels have been shown to mask relevant acoustic signals and cues, thereby affecting their antipredator behavior performance.7,8 However, little is known regarding the effects of noise on the embryonic development of laboratory zebrafish, and hence experimental bias may be inadvertently introduced into the test results.

Accordingly, the present study commenced by examining the embryonic development of zebrafish under continuous exposure to noise in a microfluidic environment for five days. The effects of this noise on the swimming speed of the hatched larvae were then investigated using a light cue technique.9,10 Finally, an acoustic method exploiting the natural spatial avoidance of larvae to sound was used to sort the individual larvae into specific chambers in the microfluidic platform. Traditional techniques for sorting, transporting, and manipulating zebrafish embryos in the microfluidic devices are described as follows. A funnel device consists of a gravity-driven pump, a funnel layer, and a microchannel layer. The embryo immobilized in the funnel and fluid in the microchannel below was separated from the fluid.11 A 3D chip with four integrated modules for in vivo analysis of angiogenesis kinetics12 of the immobilized embryos inside the trapping array (inset). With a vacuum-based embryo holding device, embryos were immobilized on the individual through-holes via a negative pressure enabling fully automated microinjection.13 Setup for imaging a larva in a microfluidic “Fish-Trap” channel for real-time brain-wide mapping at the lateral or dorsal view;14 still, all the above-mentioned methods required tedious manual processes/anesthesia, which may potentially induce temporary or permanent physiological damages (or even mortality).9,10 Moreover, manual handling procedures that are common in the previous study are time consuming, likely to introduce significant bias in results, and do not have high-throughput handing out required for drug screening. This experimental setup was progressive with the microfluidic on chip culturing together with the automated trapping offered. Specifically, the light cue and acoustic techniques employed in the present study are entirely non-invasive and hence substantially can reduce the risk of experimental bias for automated fish manipulation.9,10,15

EXPERIMENTAL SETUP AND PROTOCOLS

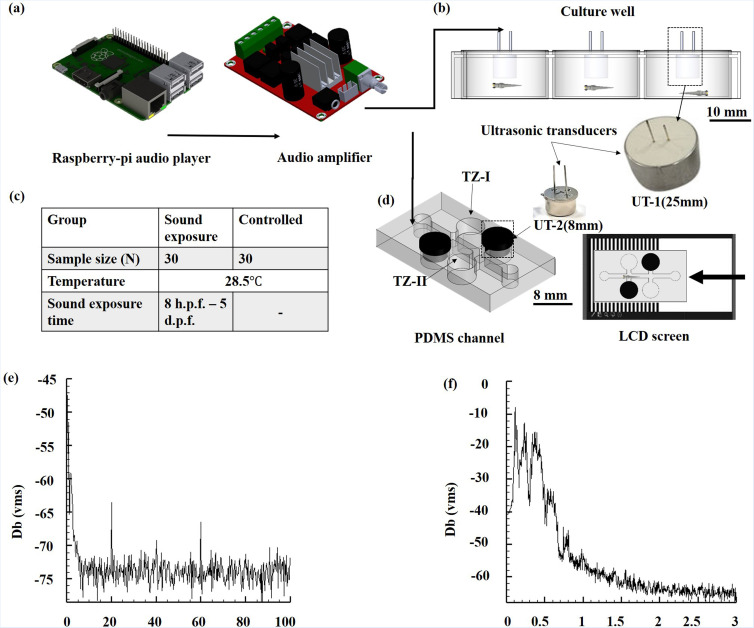

All experiments were performed under the relevant laws and institutional guidelines set by the National Cheng Kung University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) with approval number: 108269. The sound treatment test was facilitated through a raspberry Pi-3B and audio amplifier (YDA138 E, Yamaha, Japan) [see Fig. 1(a)]. The noise source had the form of a 25-mm ultrasonic transducer (UT-1, 250ET250, Pro-Wave Electronics Corporation, Taiwan) glued to the underside of a six-well plate coverslip with silicon glue. Zebrafish embryos (N = 4 dishes, 30 embryos per dish) were raised and bred in the six-well plate [see Fig. 1(b)]. During the culturing process, sound treatment was performed by playing traffic noise with the amplitude spectrum shown in Fig. 1(e) through UT-1 for five days. The water temperature was maintained at 28.5 ± 1 °C throughout the entire process with the water being partially replenished every 48 h [see Fig. 1(c)]. 8-mm ultrasonic transducers (UT-2, 400E08S, Pro-Wave Electronics Corporation, Taiwan) were additionally glued to the microfluidic device perpendicular to the trapping zones [TZ-I and TZ-II, see Fig. 1(d)]. The hatched larvae were transported toward the trapping zones by stimulating their optomotor behavioral response (OMR)9 using an LCD light pattern with a frequency of 1.5 Hz and a pattern width ratio of 1:1. Once the larvae reached the trapping zones, a trapping sound [predatory fish, see Fig. 1(f)] was played through UT-2 to drive the larvae into the chamber. The larvae response to the light and acoustic stimuli were recorded using a video camera and the captured frames were analyzed using open-source tracker software (Open Source Physics, OSP). The statistical significance of the acquired data was further analyzed through paired and independent sample t-tests using SPSS (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the experimental setup. (a) Audio system setup for acoustic control. (b) Culture dish with transducers. (c) Larvae culturing matrix. (d) Microfluidic setup for transportation and trapping of larvae using light and acoustic stimuli. (e) Noise amplitude waves were used for sound treatment. (f) Noise amplitude waves used for zebrafish trapping.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

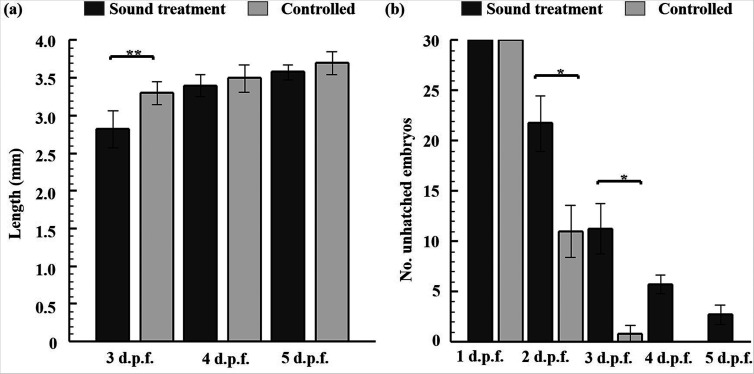

The experiments commenced by examining the effects of background noise on the embryonic development of the zebrafish (note that the larvae survival rate was not considered). A significant (*p ≤ 0.001) reduction in the average length of the larvae at 3 d.p.f. was observed between the sound-treated group (2.819 ± 0.25 mm) and the control group (3.309 ± 0.15 mm) [see Fig. 2(a)]. However, no significant difference was noted between the average lengths of the two groups at 4 d.p.f. or 5 d.p.f. The results, therefore, suggest a possible delay in hatching due to the disruption of the circadian clock chemistry of the embryos by sound treatment. The zebrafish embryos exposed to noise showed a 9.1% unhatched rate at 5 d.p.f., whereas the control group showed a zero unhatched rate [see Fig. 2(b)].

FIG. 2.

Larvae exposed to background sound for five days: (a) growth rate and (b) number of unhatched embryos. *p-value < 0.05, **p-value < 0.001 for the independent sample t-tests.

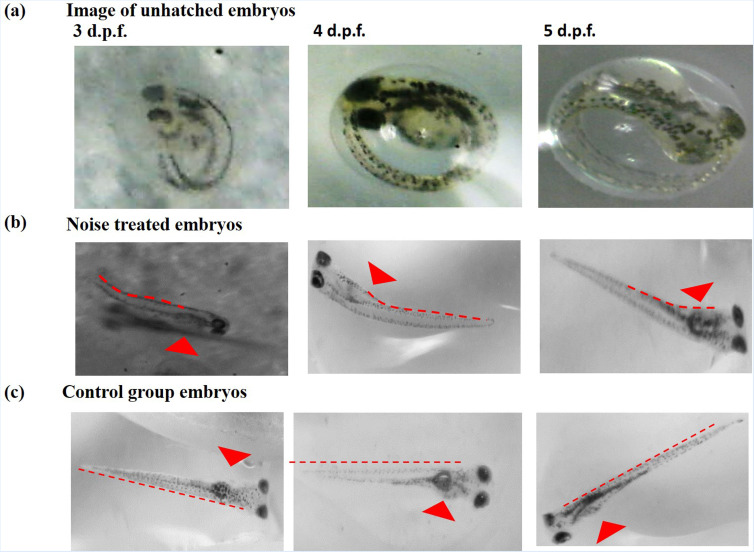

Hence, it appeared that the zebrafish embryo hatching rate was affected in response to stressful environments [see Fig. 3(a)] when exposed to increased levels of noise, and malformations were found in the trunk or tail regions [see Fig. 3(b)]. It is believed that the stress produced by noise may affect embryo metabolism, which is consistent with the previous finding.16 Larvae cultivated with background noise had yolks smaller than their ambient counterparts at a similar hatch time [see Figs. 3(b) and 3(c)]. Smaller yolks may mean less energy available to newly hatched, growing larvae, which translated to a lower growth rate compared to the control group/sound isolated group.

FIG. 3.

Images of the control group larvae of age groups at 3, 4, and 5 d.p.f. larvae. (a) Images of the sound-treated unhatched embryos and (b) images of the sound-treated larvae. The stress produced by noise led to draining yolk energy reserves and malformations in trunk or tail regions. (c) Images of the control group larvae of age groups at 3, 4, and 5 d.p.f.

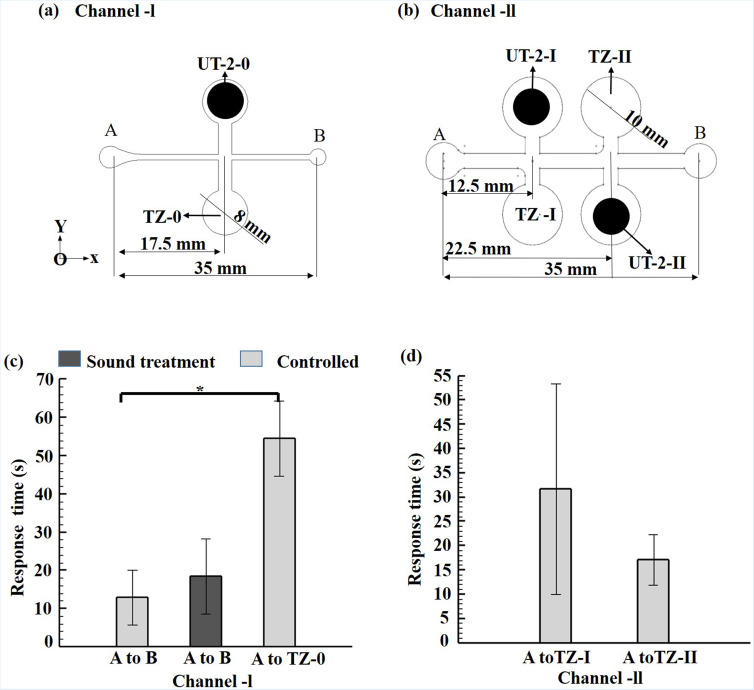

The OMR and acoustic responses of the sound-treated larvae (5 d.p.f.) were investigated and compared with those of non-sound-treated larvae (5 d.p.f.) in two microfluidic devices, designated as Channel-I and Channel-II, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4(a), the Channel-I device consists of a single trapping-zone (TZ-0) and transducer (UT-2-0). By contrast, the Channel-II device consists of two trapping zones (TZ-I and TZ-II) and two transducers (UT-2-I and UT-2-II) [see Fig. 4(b)]. The Channel-I device was first used to evaluate the OMR behavioral response of the larvae under optical stimuli. As shown in Fig. 4(c), for Channel-I, the average time required for the larvae to swim from point A to point B (i.e., the two end-points of the channel-I measuring 35 mm) was equal to 18.40 ± 9.81 s and 12.95 ± 7.13 s for the sound-treated group and control group, respectively. The difference in the swimming times of the two groups is not statistically significant. Hence, it is inferred that the larvae response to the optical stimulus is unaffected by sound treatment.

FIG. 4.

Schematic illustrations of microfluidic channel designs: (a) Channel-I and (b) Channel-II. Response times for 5 d.p.f. zebrafish larvae in control and sound treatment groups. (c) The response time shows the average swimming time from point “A” to point “B” and point “A” to TZ-0. (d) The response time of 5 d. p. f. larvae in Channel-II from point “A” to TZ-I and TZ-II. *p-value < 0.05 for the paired sample t-tests.

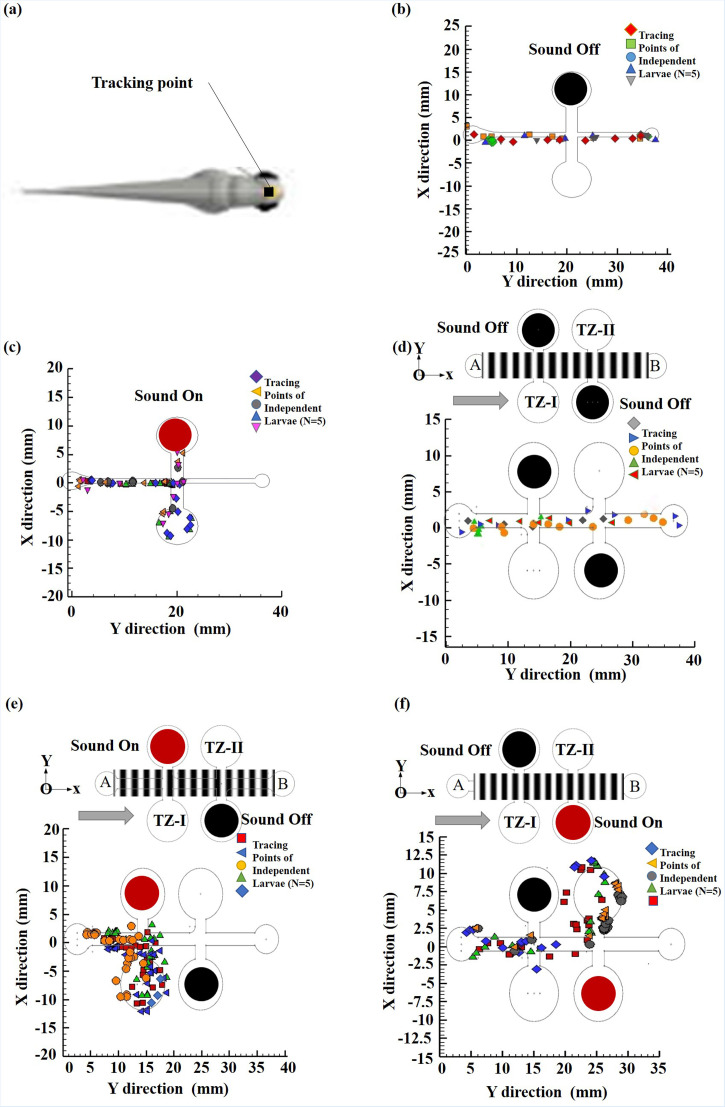

Previous studies have reported that the OMR response of zebrafish larvae is direction-specific.10 Furthermore, an escape/avoidance response can be triggered by sound at 5 d.p.f.17 Accordingly, a further experiment was performed in which UT-2-0 was turned on right after the OMR response was induced in the larvae by the LCD light pattern. The control group took 54.58 ± 22.32 s to traverse from A to TZ-0 [17.5 mm, N = 5, *p < 0.05, see Fig. 4(c)]. However, the sound-treated larvae did not respond to the acoustic stimulus and continued to swim toward point B. Thus, it was inferred that the sound treatment disrupted or damaged the mechanosensory hair cells of the larvae. To test this inference, a tracking point was selected between the eyes of the larvae on the recorded video [see Figs. 5(a), and the motion of the larvae (control group) along the channel was then plotted [see Figs. 5(b) and 5(c)], in which the solid red and black circles represent the ON and OFF states of UT-2, respectively]. In the OFF state, the zebrafish simply swam along the channel toward point B [see Fig. 5(b)]. However, in the ON state, the zebrafish ignored the light cue and turned laterally toward TZ-O in response to the acoustic stimulus [see Fig. 5(c)]. In other words, it appeared that the locomotor behavior of zebrafish larvae in microfluidic environments is dominated by an acoustic response rather than an optical response. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study,18 which showed that noise plays a key role in predatorial avoidance. Although it was observed that the larvae responded strongly to the acoustic stimulus, it is possible that, in entering TZ-0, the motion of the larvae was driven simply by a microfluidic design/natural response. Hence, an additional experiment was performed using the Channel-II device, in which the two ultrasonic transducers (UT-2-I and UT-2-II) were turned on in sequence as the larvae (control group) swam along the channel. The average times spent by the larvae in swimming from point A to TZ-1(12.5 mm) and TZ-II (22.5 mm) were found to be 31.70 ± 21.64 s and 17.12 ± 5.20 s, respectively [Fig. 4(d), N = 5]. The tracking results confirmed that most of the larvae responded to the acoustic stimuli and traversed to TZ-I and TZ-II accordingly [see Figs. 5(d)–5(f)]. Interestingly, the larvae travel time from point A to TZ-0 (Channel-I) and TZ-I (Channel-II) is higher than that from point A to TZ-II (Channel-II) despite the travel distance to TZ-II being twice that to TZ-I. It was observed that closer the transducer (UT-2-0, UT-2-I) induce anxiety/freezing behavior in response to the threat. This finding suggests that zebrafish larvae respond more strongly to acoustic stimuli located further from the inlet.

FIG. 5.

Each symbol represents tracking points of individual larvae under acoustic stimulation, in which the solid red and black circles represent the ON and OFF states of UT-2, respectively. (a) Tracking point, (b) UT-2-0-Off and (c) UT-2-0-On. Tracking points of individual zebrafish larvae within Channel-II for: (d) both UT-2-I and UT-2-II-Off, (e) UT-2-I-On, and (f) UT-2-II-On. *p-value < 0.05 for the paired sample t-tests.

Overall, the present results confirmed the importance of ensuring adequate noise isolation during the embryonic development of zebrafish. Moreover, the feasibility of the proposed non-invasive optical/acoustic method for the transportation and trapping of zebrafish larvae in microfluidic environments have been confirmed. The design of transporting larvae can further be integrated with an automated system where the larvae can be transported to the desired test zone and trapped in the desired test zone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan under Contract No. MOST 108-2221-E-006-221-MY4). The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided to this study by the Center for Micro/Nano Science and Technology at National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan. This research was supported in part by the Higher Education Sprout Project, Ministry of Education to the Headquarters of University Advancement at National Cheng Kung University.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mani K., Chang Chien T.-C., Panigrahi B., and Chen C.-Y., Sci. Rep. 6, 36385 (2016). 10.1038/srep36385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panigrahi B. and Chen C.-Y., Lab Chip 19(24), 4033–4042 (2019). 10.1039/C9LC00534J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen C. Y. and Chen C. Y., Nanotechnology 24(26), 265101 (2013). 10.1088/0957-4484/24/26/265101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Environmental Health, Pediatrics 100(4), 724 (1997). 10.1542/peds.100.4.724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claudia Harper C. L., The Laboratory Zebrafish (CRC Press, 2010), see https://www.routledge.com/The-Laboratory-Zebrafish/Harper-Lawrence/p/book/9781439807439.

- 6.Neo Y. Y., Parie L., Bakker F., Snelderwaard P., Tudorache C., Schaaf M., and Slabbekoorn H., Front. Behav. Neurosci. 9, 28 (2015). 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J., Yan Z., Xing Y., Lai K., Wang J., Yu D., Shi H., and Yin S., J. Bio-X Res. 2(2), 87–97 (2019). 10.1097/JBR.0000000000000033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris B. H., Philbin M. K., and Bose C., J. Perinatol. 20(8 Pt 2), S55–60 (2000). 10.1038/sj.jp.7200451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mani K., Hsieh Y.-C., Panigrahi B., and Chen C.-Y., Biomicrofluidics 12(2), 021101–021101 (2018). 10.1063/1.5027014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panigrahi B. and Chen C.-Y., Micromachines 10, 880 (2019). 10.3390/mi10120880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choudhury D., Noort D., Iliescu C., Zheng B., Poon K. L., Korzh S., Korzh V., and Yu H., Lab Chip 12, 892–900 (2011). 10.1039/C1LC20351G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akagi J., Zhu F., Skommer J., Hall C. J., Crosier P. S., Cialkowski M., and Wlodkowic D., Cytom. Part A 87(3), 190–194 (2015). 10.1002/cyto.a.22603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bischel L. L., Mader B. R., Green J. M., Huttenlocher A., and Beebe D. J., Lab Chip 13(9), 1732–1736 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc50099c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin X., Wang S., Yu X., Liu Z., Wang F., Li W. T., Cheng S. H., Dai Q., and Shi P., Lab Chip 15(3), 680–689 (2015). 10.1039/C4LC01186D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C.-Y., Chang Chien T.-C., Mani K., and Tsai H.-Y., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 20(1), 12 (2016). 10.1007/s10404-015-1668-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fakan E. P. and McCormick M. I., Mar. Pollut. Bull. 141, 493–500 (2019). 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgess H. A. and Granato M., J. Neurosci. 27(18), 4984–4994 (2007). 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0615-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colwill R. M. and Creton R., Rev. Neurosci. 22(1), 63–73 (2011). 10.1515/rns.2011.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.