Highlights

-

•

Patient having recurrent carcinomas following heart transplant due to possible immunosuppression.

-

•

Early Cancer surveillance in transplant patients is necessary to detect and treat malignancies early.

-

•

Unique in having two recurrences post-transplant.

Keywords: Immunosuppression, Heart transplantation, Cancer, Squamous cell carcinoma

Abstract

Introduction and importance

Solid organ transplantation has evolved along with dramatic advancements in definitive treatment for irreversible and uncompensated organ failure. Transplanted organ survival has improved as a result of reduced allograft rejection. However, negative long-term outcomes which were largely due to the adverse effects of rapidly evolving immunosuppressive regimens are still evident. The emergence of malignancies following prolonged exposure to immunosuppression treatment has affected the quality of life in transplant recipients. They are approximately one hundred times more likely to develop squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) compared to the general population and the incidence of malignant melanomas, basal cell carcinomas, and Kaposi’s sarcomas are also on the rise. The incidence of de novo malignancies ranges from 9 to 21% and is commonly seen in the skin and the lymphoreticular system in these patients.

Case presentation

A 78-year-old male presented with a lump in the right axilla, which had grown in size over a 4-week period. Patient had received a cardiac transplant 9 years prior and was on a regimen of Tacrolimus and Mycophenolate Mofetil since then.

Clinical discussion

Following 4 years of immunosuppression therapy, the patient developed a non-healing ulcer on his right forearm and the biopsy confirmed SCC. The recent biopsy performed on the new axillary lump also confirmed SCC. Iatrogenic immune suppressive treatment is associated with the occurrence of de novo, non-melanoma skin cancers in the solid organ transplant recipients and this necessitates early and comprehensive cancer surveillance models to be included in the pre and post-transplant assessment.

Conclusion

Advances in immunology suggest that peripheral blood mononuclear cell sequencing and immune profiling to identify immune phenotypes associated with keratinocyte cancers allow us to recognize patients who are more susceptible for SCC following organ transplantation and immunosuppression.

1. Introduction

Cardiac transplantation is the definitive mode of treatment for advanced heart failure in patients who would otherwise succumb to their heart disease. According to statistics from the International Thoracic Organ Transplant (TTX) Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, total heart transplants performed through June 30th, 2018 was 146,975 which included 131,249 adult heart transplants and 15,264 pediatric heart transplants. Patient survival has steadily improved since the first cardiac transplantation which took place at the Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa in December of 1967 by a team lead by Christiaan Barnard [1]. Current survival data following cardiac transplant shows a one-year survival of 84.5% and 5-year survival of 72.5% compared to 76.9% and 62.7% respectively from data in 1980 [2]. A cardiovascular surgical clinic attached to a University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland has shown survival rates at 1, 10, and 20 years to be 82.7%, 63.9%, and 55.6% respectively [3]. The two long-term complications accounting for a reduced 10-year survival are chronic allograft vasculopathy and malignancies which account for 35% of cumulative deaths after 10–15 years post-transplant [1]. Looking at the demographic registry (1988 - present) among cardiac transplant recipients in the United States, the 50–64-year age group represents the highest number of recipients (https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/citing-data/).

When considering all solid organ transplantations, older populations are the most vulnerable for its negative long-term and short-term outcomes due to their elevated morbidity and mortality risk associated with advanced age. Widely available immunosuppressive treatments play a significant role in the management of transplant related morbidity and mortality allowing an optimum graft versus host relationship resulting in prolonged graft survival which play a significant role in transplant related morbidity and mortality. Most commonly used immune suppressants following solid organ transplantation are calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) such as Ciclosporin and Tacrolimus, mTOR inhibitors (mTORi) such as Everolimus and Sirolimus and Mycophenolic Acid (MPA). An improved understanding and introduction of Ciclosporin immunosuppression regimens have led to a growing community of solid organ transplant recipients (SOTRs) due to minimal graft rejection. However, cumulative occurrences of malignancies in transplant recipients has increased, with those who received 10 years of uninterrupted immunosuppression accounting for 20% de novo malignancies while the general population reports numbers ranging from 4 to 16% [4]. The increased incidence of malignancies following organ transplantation compared to the general population has been attributed to decreased immune-surveillance, infection with oncogenic viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human papillomavirus (HPV), human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), chronic stimulation of the immune system, and immunosuppression [4].

There are 3 major categories of malignancies which occur in solid organ transplant recipients listed as de novo, recurrence of existing malignancy and those acquired through an allograft. Within the category of de novo malignancies, cutaneous and lympho-reticular varieties are the most common. Although cutaneous malignancies could be either melanoma or non-melanoma cancers, the highest incidence was reported with non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC), which have a higher morbidity and mortality in the transplant population compared to the general population. There was a study among 835 cardiac transplant recipients who survived a month or more after the solid organ transplant between 1979 and 2002, that evaluated occurrences of cutaneous carcinomas, solid organ cancers and lymphomas. In this study, 139 malignancies were observed in 126 patients (15.1%), consisting of skin cancers (49%), solid organ tumors (27%), and lymphomas (24%) [5].

In an Australian cohort of renal transplant recipients, 82.1% had at least one confirmed NMSC within 20 years following immunosuppressive treatment and approximately a third (29.1%) showed an emergence of NMSC within 5 years of immunosuppression [6]. The background of iatrogenic host immune suppression is the major reason behind increased predilection to NMSC in SOTRs, compared to individuals with inherited immunodeficiency or even Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). In particular, the risk for the development of NMSC is substantially higher in SOTRs. This finding suggests there is a direct correlation between immunosuppressive medications that stand for iatrogenic immune suppression and incidence of NMSC. Cardiac transplant recipients appear to have the highest risk of developing skin malignancies among all solid organ transplantations due to the fact that high doses and strengths of immunosuppressive medications needed during the post-transplant phase to minimize allograft rejection. This results in the possibility of developing a cancer being about 2–3 times greater than in renal transplant recipients. The cumulative incidence of NMSC following cardiac transplantation was 31% and 43% at 5 and 10 years, respectively, in an Australian cohort [7,8].

Each immunosuppressive medication regimen carries its own adverse effects. A retrospective cohort study was designed to determine skin cancer risk associated with immunosuppressants and 182 SOTRs were tracked for 1000 person-years. The results demonstrated that patients who developed skin cancer had been exposed to significantly higher cumulative doses of Cyclosporine, Azathioprine, Prednisone and Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) than those who did not [9].

This patient’s post-transplant journey was complicated by the de novo occurrence of a SCC in the 4th year and a recurrence in the 9th year following the cardiac transplant. Keratinocyte cancers (SCC and BCC) are associated with an increased risk of subsequent malignancies in the general population. This suggests a possibly enhanced genetic etiology for recurrent SCC in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression. The occurrence of cutaneous SCC following transplantation could serve as a marker for elevated risk of malignancy [10].

2. Case presentation

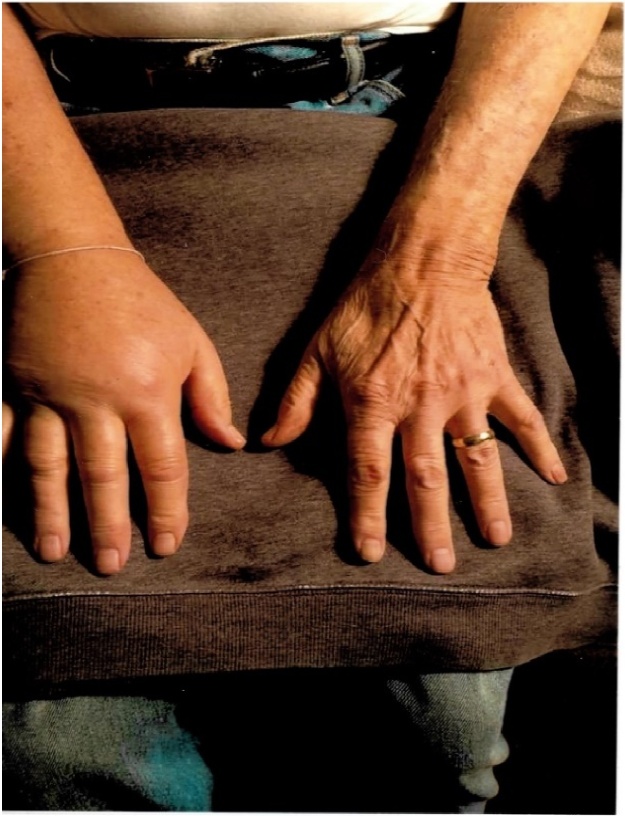

This work is been reported in line with the Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines [11]. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s next of kin for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A 78-year-old Caucasian male presented with a painless swelling of the right hand developed over a three-week period (Fig. 1). There was no history of trauma and he did not have any other symptoms such as weakness, sensory loss in the hand, neck pain, shortness of breath, fever, weight loss, or a loss of appetite. He had noticed a painless lump in his right axilla four weeks prior to the development of swelling in the right hand. The axillary nodule enlarged rapidly to a size of 2″ X 2″ over a 4-week period (Fig. 2). His past medical history was unremarkable until 10 years ago when he was diagnosed with fulminant viral myocarditis that subsequently progressed to a dilated cardiomyopathy. A year later, he underwent a cardiac transplant. He was kept on a regimen of Tacrolimus 0.5 mg every 12 h, in addition to 500 mg of MMF twice daily. Four years later, the patient consulted a dermatologist for a non-healing ulcer on his right forearm. The lesion was removed with a wide excision, and the biopsy confirmed squamous cell carcinoma. Excision of skin was free of tumor margins. There was no evidence of metastatic disease, and he was followed up by the dermatologist every 3–6 months.

Fig. 1.

Swollen right hand compared with the left hand.

Fig. 2.

Lump in the right axilla measuring 2″ X 2″.

At presentation, this patient had been treated with Tacrolimus and MMF since his cardiac transplantation ten years ago. Upon examination, non-pitting swelling of the right hand and forearm were noted. A firm, non-tender lump measuring 2″ X 2″ was noticed in the right axilla with mild induration around the lesion. A CT scan of the chest showed a lung nodule 1 cm in diameter, but the biopsy was negative for malignancy. The patient’s MRI and PET scans did not show any evidence of metastatic disease. The axillary lump was surgically removed, and the biopsy confirmed squamous cell carcinoma.

3. Discussion

Long-term maintenance immunosuppressive therapy is the mainstay of post-transplant management in order to increase host tolerance to the transplanted organs. The goal of immune suppression is to adapt a T cell tolerance in the host immune cell environment to overcome the immune mechanism in transplant rejection which is driven by specific T cell immunity, directed against major and minor histocompatibility antigens in the allograft. Simply put, T cell tolerance implies creating an inadequate response to allo-antigens. Common mechanisms associated with T cell tolerance are anergy, immune-regulation, clonal exhaustion and ignorance. Currently, clinically used immune-suppressants target immune-depletion or blockage of one of the three steps of T-cell activation (antigen recognition, co-stimulation and proliferation/differentiation). A combination of induction and maintenance treatment augments the therapeutic potential to prevent transplant rejection. Most of the induction therapies concentrate on profound immune cell depletion at the time of transplantation when immune activation is most intense. Thus, the predominant side effect seen is severe life-threatening infections during this acute phase. Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), Anti CD52 mAb (Alemtuzumab), Anti CD3 mAb, Anti-α, β TCR antibodies, Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 immunoglobulin (CTLA-4), and Anti-IL-2R mAb (Basiliximab and Daclizumab) are among some of the currently used induction agents. However, the occurrence of malignancy is not an identified risk factor of treatment with these induction agents [12].

Maintenance immunosuppressant therapy contributes to an increased risk for malignancy in SOTRs. Combinations of two or more of Azathioprine, Cyclosporine, Methotrexate, Mycophenolate Mofetil, Sirolimus, Steroids, Tacrolimus, and Fingolimod are frequently used in maintenance regimens. Skin is the most common site for the development of such malignancies, particularly cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (CSCC) and basal cell carcinomas (BCC), both composing Non-Melanoma Skin cancers. A variety of factors, such as the intensity and duration of immunosuppression, ethnic background of the patient, exposure to the sun, and geographic location can all influence the likelihood for the development of skin cancers in these patients. However, along with improved survival following solid organ transplants, the risk of skin cancer is proportionately elevated as it prolongs the exposure to immune suppressants causing defective host immune surveillance.

Calcineurin inhibitors, Cyclosporine, Tacrolimus and purine synthesis inhibitors like Azathioprine and MMF are among the drugs used in the maintenance pace of the immune suppression. These drugs suppress the immune system so that it will accept the transplanted organ and not attack it. The incidence of skin cancer in SOTRs is common, and this risk is further exacerbated by advanced age, Caucasian race, male sex, and thoracic organ transplantation. Understanding the risk factors and trends in post-transplant skin cancer is fundamental to targeted screening and prevention in such a population [13]. Squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common skin malignancy after basal cell carcinoma in the general population, is frequently found in transplant patients, accounting for 65–250 times more in this population [14]. Melanoma occurs 6–8 times more frequently. Basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s Sarcoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma (a virulent but normally rare skin malignancy) are also commonly seen in SOTRs.

Management of a post-cardiac transplant patient is different from other solid organ transplant recipients because they require a higher level of immunosuppression to counteract the high risk of death associated with organ rejection. The relationship between an increased level of immunosuppression and the likelihood of malignancy is well-demonstrated [15]. In 1970, Burnet proposed that the immune system was responsible for the recognition of specific antigens present on the cancer cell surface and for the destruction of the emerging cancer clone, which is the concept of immunological surveillance of cancer. According to this theory, immune deficient populations should experience, higher incidence in all types of cancers [16]. If immune deficiency is associated with such a broad range of cancers, it will raise a major concern that cancer is likely to become an increasingly important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS [17]. This is not always the case. Instead, this shows that lifestyle-related risk factors for cancers may differ quite substantially between these populations. If patterns of the incidence of cancers are similar, then it would be more likely that immune deficiency is primarily responsible [17]. However, the risk of skin cancer among individuals with AIDS or naturally occurring immunodeficiency conditions, does not approach the levels seen in organ transplant recipients, suggesting that individuals in this population carry another risk in common to factoring more incidences. Focusing on the tumor characteristics also revealed a significant aggressive behavior among skin cancers which demonstrate the development of tumor metastases, 1.4 years following the diagnosis of the primary skin cancer in transplant recipients compared to the general immunocompetent population [14,22].

There is evidence suggesting that Calcineurin inhibitors interfere with p53 signaling and nucleotide excision repair (NER). These two pathways are associated with non-melanoma skin cancers in general and squamous cell carcinomas in particular. This finding may help explain the predominance of squamous cell carcinomas compared to basal cell carcinomas in this population. Mammalian targets of Rapamycin inhibitors (mTORi) do not appear to impact these pathways. Immunosuppression, viral infection, impaired DNA repair, and p53 signaling all interact in organ transplant recipients to create a phenotype of extreme risk for non-melanoma skin cancers [18]. In clinical trials switching from Calcineurin inhibitors to Rapamycin inhibitors consistently led to a significant reduction in the risk for developing new skin cancers. Hence researchers are guided to find the contribution of each class of immune suppressants in the generation of malignant clones. The cumulative incidence of skin cancers and other non-lymphoma cancers increased with age at cardiac transplantation (CT) and with time post-cardiac transplantation (from 5.2 and 8.9 per 1000 person-years in the first year to 14.8 and 12.6 in the 10th year, respectively). Incidence was also greater in men compared to women, the age at transplant >45 years, use of induction therapy, and a high level of exposure to the sun, Caucasian race, lighter skin, type of immunosuppressant used, duration of use, dosage levels, low Fitzpatrick skin types, subsequent solid organ re-transplantation, heart or lung transplantation (with a lower risk seen in liver or kidney transplantation), Calcineurin inhibition (via Cyclosporine or Tacrolimus), Azathioprine for SCC risk, mTOR inhibitors (Everolimus, Sirolimus), Mycophenolate Mofetil, and Voriconazole use were noted as risk factors for both SCC and BCC following transplantation [[18], [19], [20], [21]].

NER is the exclusive repair mechanism for the two most common UV-mediated types of DNA damage leading to photo-carcinogenesis - Cyclobutane Pyrimidine dimers (CPD) and pyrimidine-6,4-pyrimidone photoproducts (6-4PP) [22,23]. Further, the increased potential for malignancy was demonstrated through an increased production of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-ß), potentiation of the oncogene ATF3, decreased apoptosis following UVB and interruption of nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) [22,24]. Cyclosporine which represents the prototype of CNI was in use as the first-line immunosuppressant for most SOTRs and it was strongly proven through many data sets to increase the occurrence of skin cancers [25,26]. SCC, which is the most common among NMSCs in SOTRs on Cyclosporine, has shown a dose dependent relationship with cyclosporine [27]. The combination treatment of Cyclosporine A, Azathioprine and Prednisolone demonstrated close to a 3-fold higher skin cancer risk compared with a regimen of azathioprine and prednisolone only [27].

Tacrolimus is next in the CNI group and it has largely replaced the use of Cyclosporine. But it is less evident whether skin cancer is more or less frequent in SOTRs treated with Tacrolimus compared to Cyclosporine. Many studies have found both supporting and contradicting evidence for the hypothesis that tacrolimus causes a lower incidence of skin cancers compared to cyclosporine [[28], [29], [30], [31]]. This drug has a dose-dependent effect on the progression of tumors related to TGF-beta 1 expression. Tacrolimus-induced over expression of TGF-beta 1 may be a pathogenic mechanism in the progression of tumors [32]. MMF impairs lymphocyte function by blocking purine biosynthesis via inhibition of the enzyme Inosine Monophosphate Dehydrogenase. MMF modulates adhesion receptors of the beta-1 integrin family on tumor cells, reducing the recurrence of tumors and malignancy. A recent study suggests that the increased risk of CSCC historically associated with Azathioprine is not seen in organ transplant recipients prescribed newer regimens, including MMF and Tacrolimus [33].

Tacrolimus and MMF impair the repair of UVB induced DNA and apoptosis in human epidermal keratinocytes. Further, Tacrolimus inhibits UVB induced check point signaling. However, MMF had no effect. This finding demonstrates that Tacrolimus compromises a proper UVB response in keratinocytes, suggesting an immunosuppression-independent mechanism in the tumor-promoting action of these immunosuppressants [34]. Everolimus and Sirolimus are from the mTOR inhibitor group and mostly used when tacrolimus is not tolerated or contraindicated. These medications demonstrated no inhibition of NER, retained residual T cell memory function and a lower potential for angiogenesis [35,36]. Antitumor activity of mTOR inhibitors was also demonstrated in already developed cancers [37]. It’s use is limited by a profile of side effects, it is still used in the early conversion to mTORi therapy from CNIs to reduce the CNI dose by early simultaneous administration of mTORi [38].

A minimum of four different viruses may be co-carcinogenic in transplanted patients. They are the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), human papillomavirus (HPV), and Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV). Even though a clear mechanism is not explained, data shows that the beta genus HPV is associated with risks for SCC [39]. Azathioprine is directly related to UVA mediated DNA mutagenesis [40]. Mechanism of photocarcinogens is a cumulative effect of UV induced direct DNA damage, UV effect on host immunity and synergism with other drug affected molecular pathways [41]. Isolation of the high-risk population with biological and environmental factors, molecular cytogenetics and immune profiling will also aid in realizing their predisposition to post transplant carcinoma types and in terms of effective and rational use of immunosuppression medication regimes to suit the individual risk. Based on the specific patient and tumor-related data, adjusted tumor suppression regimens should be individualized [36,42]. To identify high-risk populations by a multifactorial association model, a clinically derived predictive index was developed to calculate the risk of developing SCC in transplant recipients [43].

It was recognized that the presence of high numbers of regulatory T cells (CD4+CD25highFOXP3+and CD8+CD28−cells) in the tumor or in the peripheral blood is linked with a poor prognosis of a cancer in the general population. Recent advancements in deep immune profiling and understanding of different immune phenotypes with immune cell subsets explain immune signatures of the tumor micro-environment which will provide a lead to early identification of individuals at risk of developing SCC following solid organ transplantation. In two studies where lymphocyte subsets were measured to map with the risk of SCC, reduced CD4 + T cells were found in individuals at risk of developing any cancer including SCC following transplantation [44]. Very important findings from a large study on immune phenotyping of peripheral blood mono nuclear cells (PBMC) showed kidney transplant recipients (KTR) with previous SCC have a higher number of FOXP3+CD4+CD127lowand CD8+CD28−T cells present in the peripheral blood than KTRs without SCC. Hence, new tumor development is associated with a low CD8/FOXP3 ratio [45].

A better understanding of the above aspects can improve the post-transplant surveillance by adjusting immunosuppressant regimens considering risk factors known to enhance the occurrence of solid organ tumors in transplant recipients. Reappraisal of pre- and post-transplant cancer surveillance tools or models will play an important role for early identification of a growing number of carcinomas associated with solid organ transplantation. We are in an era where acute rejection is no longer a burden following organ transplantation. That said, the long-term outcome from carcinomas affect the quality of life since it absolutely increases transplant-associated morbidity and mortality.

4. Conclusion

While the growing community of solid organ transplant recipients overcome the problem of allograft rejection through advanced T cell tolerance mechanisms applied through immunosuppressive regimens, it is evident that immunosuppression is increasing the incidence of malignancy. The emergence of NMSC can occur as a direct result of immune suppressive agents, activation of carcinogenic viruses or by the disruption of immunosurveillance mechanisms, resulting in carcinogenesis. These are among the well-recognized pathways for the majority of NMSC, identified following solid organ transplantation. Deep immune profiling has recognized immune cell phenotypes which are associated with skin cancers following exposure to immune suppressive regimens. Cardiac transplant recipients are particularly at risk of such malignancies and should be monitored more closely focusing on risk assessment strategies/indexes, and pre and post-transplant vigilant cancer screening tools.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Patient deceased.

Consent

Not applicable.

Author contribution

Anushka Ruawanpathrina – literature search and data analysis

Saman Fernando – first draft of article and data analysis

Vinati Molligoda – data analysis

Jay G. Fernando – data analysis and critical review

Wei Zhang – critical review

Shyamal Premaratne – final article submission and critical review

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

N/A.

Provenance and pee review

Not commissioned, externally per-reviewed.

References

- 1.Khush K.K., Cherikh W.S., Chambers D.C. The international thoracic organ transplant registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: thirty-fifth adult heart transplantation report-2018; focus theme: multiorgan transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37(10):1155–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karen S., Peter Z. 50th anniversary of the first human heart transplant how is it seen today? Eur. Heart J. 2017;38(46):3402–3404. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez C.B.H., Sündermann S.H., Emmert M.Y. Surviving 20 years after heart transplantation: a success story. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014;97:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajithkumar T.V., Parkinson C.A., Butler A., Hatcher H.M. Management of solid tumors in organ-transplant recipients. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(10):921–932. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yagdi T., Sharples L., Tsui S., Large S., Parameshwar J. Malignancy after heart transplantation: analysis of 24-year experience at a single center. J. Card. Surg. 2009;24(5):572–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2009.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsay H.M., Fryer A.A., Hawley C.M., Smith A.G., Harden P.N. Non-melanoma skin cancer risk in the Queensland renal transplant population. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002;147(5):950–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krynitz B., Edgren G., Lindelof B., Baecklund E., Brattstrom C., Wilczek H., Smedby K.E. Risk of skin cancer and other malignancies in kidney, liver, heart and lung transplant recipients 1970 to 2008: a Swedish population-based study. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;132(6):1429–1438. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ong C.S., Keogh A.M., Kossard S., Macdonald P.S., Spratt P.M. Skin cancer in Australian heart transplant recipients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colegio O.R., Billingsley E.M. Skin cancer in transplant recipients, out of the woods. Scientific retreat of the ITSCC and SCOPE. Am. J. Transplant. 2011;11(8):1584–1591. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zamoiski R.D., Yanik E., Gibson T.M. Risk of second malignancies in solid organ transplant recipients who develop keratinocyte cancers. Cancer Res. 2017;77(15):4196–4203. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Kerwan A., SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Getts D.R., Shankar S., Chastain E.M.L., Martin A., Getts M.T. Current landscape for T-cell targeting in autoimmunity and transplantation. Immunotherapy. 2011;3(7):853–870. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett G.L., Blanc P.D., Boscardin J. Incidence of and risk factors for skin cancer in the organ transplant recipients in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(3):296–303. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Euvard S., Kanitakis J., Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(17):1681–1691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarty J.M. Massey cancer center, Virginia commonwealth university school of medicine, Richmond, Virginia. Pers. Commun. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnet F.M. The concept of immunological surveillance. Prog. Exp. Tumor Res. 1970;13:1–27. doi: 10.1159/000386035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grulich A.E., van Leeuwen M.T., Falster M.O., Vajdic C.M. Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370(9581):59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheless L., Jacks S., Mooneyham Potter K.A., Leach B.C., Cook J. Skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: more than the immune system. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014;71(2):359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crespo-Leiro M.G., Alonso-Pulpon L., Vázquez de Prada J.A. Malignancy after heart transplantation: incidence, prognosis and risk factors. Am. J. Transplant. 2008;8(5):1031–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molina B.D., Leiro M.G., Pulpón L.A. Incidence and risk factors for nonmelanoma skin cancer after heart transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2010;42(8):3001–3005. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen P., Hansen S., Moller B., Leivested T., Pfeffer P., Geiran O., Fauchald P., Simonsen S. Skin Cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-tern immunosuppressive therapy regimens. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40(2 Pt 1):177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yarosh D.B., Pena A.V., Nay S.L., Canning M.T., Brown D.A. Calcineurin inhibitors decrease DNA repair and apoptosis in human keratinocytes following ultra violet B irradiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005;125(5):1020–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard M.D., Su J.C., Chong A.H. Skin cancer following solid organ transplantation: a review of risk factors and models of care. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2018;19(4):585–597. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dziunycz P., Lefort K., Wu X., Freiberger S., Neu J., Djerbi N. The oncogene ATF3 is potentiated by cyclosporine A and ultraviolet light a. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2014;134(7):1998–2004. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen P., Hansen S., Møller B., Leivestad T., Pfeffer P., Geiran O. Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40(2):177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufmann R., Oberholzer P., Cazzaniga S., Hunger R. Epithelial skin cancers after kidney transplantation: a retrospective single center study of 376 recipients. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2016;26(3):265–270. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2016.2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen P., Hansen S., Møller B., Leivestad T., Pfeffer P., Fauchald P. Are renal transplant recipients on CsA-based immunosuppressive regimens more likely to develop skin cancer than those on azathioprine and prednisolone? Transpl. Proc. 1999;31(1–2):1120. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crespo-Leiro M., Alonso-Pulpon L., Vázquez de Prada J., Almenar L., Arizon J., Brossa V. Malignancy after heart transplantation: incidence, prognosis and risk factors. Am. J. Transplant. 2008;8(5):1031–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ming M., Zhao B., Qiang L., He Y.-Y. Effect of immunosuppressants tacrolimus and Mycophenolate Mofetil on the keratinocyte UVB response. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015;91(1):242–247. doi: 10.1111/php.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu X., Nguyen B., Dziunycz P., Chang S., Brooks Y., Lefort K. Opposing roles for calcineurin and ATF3 in squamous skin cancer. Nature. 2010;465(7296):368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature08996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasiske B., Snyder J., Gilbertson D., Wang C. Cancer after kidney transplantation in the United States. Am. J. Transplant. 2004;4(6):905–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maluccio M., Sharma V., Lagman M., Vyas S., Yang H., Li B., Suthanthiran M. Tacrolimus enhances transforming growth factor-beta 1 expression and promotes tumor progression. Transplantation. 2003;76(3):597–602. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000081399.75231.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coghill A.E., Johnson L.G., Berg D., Resler A.J., Leca N., Madeleine M.M. Medications and squamous cell skin carcinoma: nested case-control study within the skin cancer after organ transplant (SCOT) cohort. Am. J. Transplant. 2016;16(2):556–573. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ming M., Zhao B., Qiang L., He Y.Y. Effect of immunosuppressants tacrolimus and Mycophenolate Mofetil on the keratinocyte UVB response. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015;91(1):242–247. doi: 10.1111/php.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung J.-W., Overgaard N.H., Burke M.T., Isbel N., Frazer I.H., Simpson F. Does the nature of residual immune function explain the differential risk of non-melanoma skin cancer development in immunosuppressed organ transplant recipients? Int. J. Cancer. 2016;138(2):281–292. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kauffman H.M., Cherikh W.S., Cheng Y., Hanto D.W., Kahan B.D. Maintenance immunosuppression with target-of-rapamycin inhibitors is associated with a reduced incidence of de novo malignancies. Transplantation. 2005;80(7):883–889. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000184006.43152.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meier F., Guenova E., Clasen S., Eigentler T., Forschner A., Leiter U. Significant response after treatment with the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in metastatic melanoma patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009;60(5):863–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim W.H., Eris J., Kanellis J., Pussell B., Wiid Z., Witcombe D. A systematic review of conversion from calcineurin inhibitor to mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors for maintenance immunosuppression in kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2014;14(9):2106–2119. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouwes B.J.N., Feltkamp M.C.W., Green A.C. Human papillomavirus and post-transplantation cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a multicenter, prospective cohort study. Am. J. Transplant. 2018;18(5):1220–1230. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Donovan P., Perrett C.M., Zhang X., Montaner B., Xu Y.-Z., Harwood C.A. Azathioprine and UVA light generate mutagenic oxidative DNA damage. Science. 2005;309(5742):1871–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.1114233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng J.C., Cumming S., Leung V., Chong A.H. Accrual of nonmelanoma skin cancer in renal-transplant recipients: experience of a Victorian tertiary referral institution. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2014;55(1):43–48. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otley C.C., Berg D., Ulrich C., Stasko T., Murphy G.M., Salasche S.J., Christenson L.J., Sengelmann R., Loss G.E., Jr., Garces J. Reduction of immunosuppression for transplant associated skin cancer: expert consensus survey. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006;154(3):395–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carroll R.P., Ramsay H.M., Fryer A.A., Hawley C.M., Nicol D.L., Harden P.N. Incidence and prediction of nonmelanoma skin cancer post-renal transplantation: a prospective study in Queensland, Australia. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003;41(3):676–683. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thibaudin D., Alamartine E., Mariat C., Absi L., Berthoux F. Long-term kinetic of T-Lymphocyte subsets in kidney-transplant recipients: influence of anti-T-cell antibodies and association with post-transplant malgnancies. Transplantation. 2005;80(10):1514–1517. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000181193.98026.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carroll R.P., Segundo D.S., Hollowood K., Marafioti T., Clark T.G., Harden P.N., Wood K.J. Immune phenotype predicts risk for post-transplantation squamous cell carcinoma. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21(4):713–722. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]