Abstract

Introduction

Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC; IMLYGIC®, Amgen Inc.) is an oncolytic immunotherapy approved in Europe for the treatment of unresectable metastatic melanoma (stage IIIB–IVM1a). This study characterised real-world use of T-VEC in four European countries.

Methods

Data on demographics, treatment pattern, safety, and clinical effectiveness were examined in a retrospective chart review of patients with stage IIIB–IVM1a unresectable melanoma treated with T-VEC in surgical (the Netherlands) and medical (Austria, Germany, UK) oncology settings.

Results

Overall, 66 patients were included (the Netherlands: n = 31; Austria, Germany, UK: n = 35). The median age was 69 years and 59.1% were female. At the time of T-VEC initiation, 47 patients (71.2%) had stage IIIB/C disease; of these, 30 were from the Netherlands. Although 72.7% patients overall received T-VEC as first-line therapy, this was higher in the Netherlands than the other countries (93.5% vs 54.3%). Of the 47 patients who discontinued T-VEC, 26 (55.3%) had no remaining injectable lesions (potentially indicating complete response); 20/26 of these patients were from the Netherlands. One patient discontinued T-VEC due to toxicity.

Conclusion

This study is the first comprehensive multinational evaluation of the use of T-VEC to treat unresectable stage IIIB/C–IVM1a melanoma in real-world clinical practice in Europe. The differences between European countries were apparent, with physicians in the Netherlands using T-VEC in patients with earlier advanced disease stage and in the first-line setting compared with other countries.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-020-01590-w.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Injectable, Lesion, Melanoma, Oncolytic, Real-world study, Skin cancer, T-VEC, Talimogene laherparepvec, Tumour

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC; IMLYGIC®, Amgen Inc.) is the first oncolytic immunotherapy to be approved in Europe for the local treatment of unresectable metastatic stage IIIB/C–IVM1a melanoma. |

| This study is the first comprehensive multinational evaluation of the use of T-VEC to treat unresectable stage IIIB/C–IVM1a melanoma in real-world clinical practice in Europe; the objectives of this study were to describe patient characteristics (demographics, clinical and melanoma disease history), use of T-VEC and other melanoma treatments, adverse events of interest, and clinical outcomes. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Differences in the use of T-VEC between European countries were apparent, with physicians in the Netherlands using T-VEC in patients with lower disease burden and in the first-line setting, which appears to lead to potentially improved outcomes. |

| Favourable tolerability was observed. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.13295930.

Introduction

Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC; IMLYGIC®, Amgen Inc.) is the first oncolytic immunotherapy to be approved in Europe, the USA, and Australia [1]. It is a genetically modified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 designed to selectively replicate in a broad variety of tumour cells to induce oncolysis, and contains key safety features that limit replication in normal cells [1–3]. Tumour lysis results in (1) release of replicated viruses, which can infect surrounding tumour cells, propagating the local oncolytic and innate immune effects of T-VEC; and (2) release of tumour-derived antigens, which induces adaptive, tumour-specific immune responses [2–6].

T-VEC approvals were based on the pivotal phase 3 OPTiM trial, a randomised, multinational, open-label trial in 436 patients with unresectable stage IIIB–IVM1c melanoma [7]. In OPTiM, T-VEC treatment significantly improved the durable response rate (i.e. continuous complete or partial response for at least 6 months) compared with a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) control (16% vs 2%) [7]. It led to a higher overall response rate (ORR) (26% vs 6% with GM-CSF alone). A subanalysis in patients with stage IIIB–IVM1a disease suggested greater efficacy, with an ORR of 40.5% for T-VEC versus 2% for GM-CSF, and increased overall survival (41.1 months with T-VEC vs 21.5 months with GM-CSF) [8]. Consequently, T-VEC was approved in Europe in December 2015 for the treatment of regionally or distantly metastatic unresectable melanoma (stage IIIB–IVM1a) with no brain, bone, lung, or other visceral disease [1]. In OPTiM, T-VEC was well tolerated and most adverse events (AEs) were self-limiting [1, 9]. The most common were fatigue, chills, pyrexia, influenza-like illness, and nausea [7].

OPTiM enrolled patients between 2009 and 2011 and was, as with all randomised clinical trials, conducted in a select patient population. Additional therapeutic advances have changed the melanoma treatment landscape in recent years. Studies in real-world practice are therefore needed to understand the effectiveness and tolerability of T-VEC in a broader patient population with different demographic/disease characteristics, as well as after different prior therapies in a new treatment landscape [10]. Since T-VEC approval in 2015, several retrospective studies have examined its use for the treatment of unresectable melanoma in real-world clinical practice in the USA [11–15] and Europe [16–18]. All found T-VEC to be well tolerated, with the most common AEs being mild influenza-like symptoms, e.g. fever, chills, or fatigue.

We performed a retrospective chart review study of patients with stage IIIB–IVM1a unresectable melanoma treated with T-VEC in four European countries (Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, and Austria). Data for Germany have been reported previously [18]. The objectives were to describe patient characteristics (demographics, clinical and melanoma disease history), use of T-VEC and other melanoma treatments, AEs of interest, and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

Patients aged at least 18 years with a diagnosis of unresectable melanoma stage IIIB, IIIC, or IVM1a (according to the AJCC 7th edition [19]), with no bone, brain, lung, or visceral disease, who had received at least one dose of T-VEC as per the European marketing authorisation, were included from Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, and Austria. Patients were excluded if they had previously received T-VEC in a clinical trial/expanded access programme. Data were collected from the date of primary melanoma diagnosis to the end of the observation period, i.e. the date at which the patient’s clinic joined the study.

Pseudo-anonymised data extracted from patient medical charts included sex; age; melanoma history; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, BRAF status, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, and HSV serostatus at first T-VEC dose; T-VEC use (dose concentration, dates, injected volumes); AEs; other melanoma treatments before/after T-VEC; and clinical outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were descriptive, with no hypothesis testing. Summary statistics were used for continuous variables (mean, standard deviation, median, quartiles, minimum and maximum) and for categorical variables (numbers and percentages). The data are presented for all four countries combined, and stratified by Austria, Germany, and the UK (dermato-oncology/medical oncology treatment settings) versus the Netherlands (surgical oncology setting) given the different treatment and management practices in the dermato-oncology/medical oncology versus surgical oncology settings. Individual data for Austria, Germany, and the UK are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Ethics

This study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Approval was obtained from institutional ethics committees and review boards from all institutions (Supplementary Table S1), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Results

Study Population

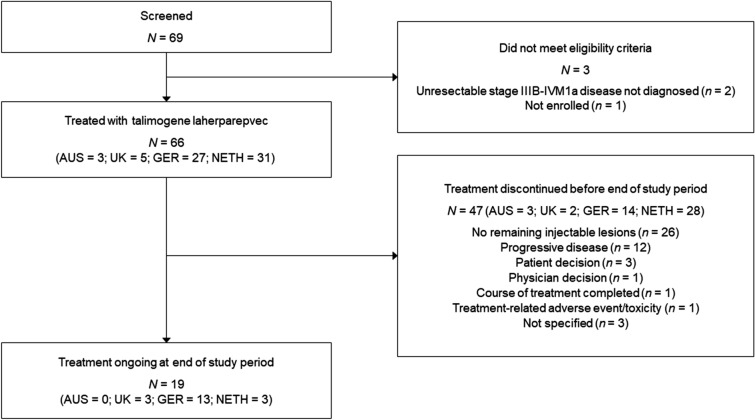

Of 69 patients screened for the medical chart review, 66 met the study eligibility criteria and were included (Fig. 1). Patients received their first treatment with T-VEC between 22 June 2016 and 22 November 2018. Patient demographic and disease characteristics are summarised in Table 1 for surgical oncology (Netherlands) versus dermato-oncology (Austria, Germany, and UK) settings, and are shown separately for Austria, Germany, and the UK (Supplementary Table S2). The median age of patients was 69 years and 59.1% were female. Approximately three-quarters of patients (71.2%) had stage IIIB/C disease and 14 patients (21.2%) had stage IVM1a disease defined prior to initiation of T-VEC. Nearly all patients from the Netherlands had stage IIIB/C disease (96.8%), compared with less than half in Austria, Germany, and the UK (48.6%).

Fig. 1.

Patient disposition. AUS Austria, GER Germany, NETH the Netherlands, UK United Kingdom

Table 1.

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics at first dose of talimogene laherparepvec

| Patient characteristic | Austria, Germany, UK (n = 35) | Netherlands (n = 31) | Total (N = 66) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| Median (range) | 68 (26–90) | 70 (42–90) | 69 (26–90) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 16 (45.7) | 11 (35.5) | 27 (40.9) |

| Female | 19 (54.3) | 20 (64.5) | 39 (59.1) |

| Median period since primary diagnosis, years, median (range)a | 3.1 (0.9–18.3) | 2.2 (0.2–18.5) | 2.7 (0.2–18.5) |

| Disease stage, n (%)a | |||

| IIIB/C | 17 (48.6) | 30 (96.8) | 47 (71.2) |

| IVM1a | 13 (37.1) | 1 (3.2) | 14 (21.2) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 13 (37.1) | 23 (74.2) | 36 (54.5) |

| 1 | 7 (20.0) | 7 (22.6) | 14 (21.2) |

| 2 | 1 (2.9) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (3.0) |

| Unknown | 14 (40.0) | 0 | 14 (21.2) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, n (%) | |||

| ≤ ULN | 20 (57.1) | 30 (96.8) | 50 (75.8) |

| > ULN | 12 (34.3) | 1 (3.2) | 13 (19.7) |

| < 1.5 × ULN | 32 (91.4) | 31 (100) | 63 (95.5) |

| ≥ 1.5 × ULN | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 3 (8.6) | 0 | 3 (4.5) |

| BRAF status, n (%) | |||

| Mutated | 9 (25.7) | 15 (48.4) | 24 (36.4) |

| Wild-type | 21 (60.0) | 11 (35.5) | 32 (48.5) |

| Unknown | 5 (14.3) | 5 (16.1) | 10 (15.2) |

ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, T-VEC talimogene laherparepvec, ULN upper limit of normal range

aAmerican Joint Committee on Cancer, Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edition [19]. Exact staging information not provided for five patients from Austria, Germany, and UK. Staging was at the time of T-VEC initiation

All patients had LDH < 1.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN) and 36.4% had a BRAF mutation. Median time from primary diagnosis to treatment with T-VEC was longer for Austria, Germany, and the UK (3.1 years) compared with the Netherlands (2.2 years).

Prior Treatments

The treatment histories of patients prior to first T-VEC administration are summarised in Table 2, and are shown separately for Austria, Germany, and the UK (Supplementary Table S3). All patients had undergone previous surgery for melanoma. Overall, 57.6% had undergone excision for recurrence, including 67.7% of patients from the Netherlands and 48.6% from Austria, Germany, and the UK. Patients in the Netherlands had undergone fewer prior excisions than patients in Austria, Germany, and the UK (median of 1.0 vs 3.0). The median time from the most recent resection for recurrent disease to initiating T-VEC was 7.4 months and was shorter for the Netherlands than for the other three countries (6.2 vs 10.0 months). In the Netherlands, no patients received adjuvant therapy during the study period. In contrast, 34.3% of patients in Austria, Germany, and the UK received adjuvant therapy after the latest procedure and before T-VEC.

Table 2.

Treatment history prior to talimogene laherparepvec administration

| Treatment history before initiating T-VEC | Austria, Germany, UK (n = 35) | Netherlands (n = 31) | Total (N = 66) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Surgery, N (%) | 35 (100) | 31 (100) | 66 (100) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |||

| Recorded resection of recurrent disease | 17 (48.6) | 21 (67.7) | 38 (57.6) |

| Sentinel biopsy | 18 (51.4) | 9 (29.0) | 27 (40.9) |

| Lymphadenectomy | 17 (48.6) | 7 (22.6) | 24 (36.4) |

| No. of resections for recurrent disease per patient, median (IQR; range) | 3.0 (1, 4; 1–11) | 1.0 (1, 3; 1–10) | 2.0 (1, 4; 1–11) |

| Months from most recent resection for recurrent disease to initiating T-VEC, median (IQR; range) | 10.0 (4, 22; 2–77) | 6.2 (4, 11; 2–45) | 7.4 (4, 15; 2–77) |

| Adjuvant therapy, N (%) | 12 (34.3) | 0 | 12 (18.2) |

| Local (intralesional therapy injection of IL-2 or IFNα) | 3 (25.0) | 0 | 3 (25.0) |

| Systemic (IFNα) | 12 (100) | 0 | 12 (100) |

| Locoregional therapy, N (%) | 17 (48.6) | 12 (38.7) | 29 (43.9) |

| Radiation therapy | 14 (82.4) | 1 (8.3) | 15 (51.7) |

| Local ablation therapy | 1 (5.9)a | 5 (41.7) | 6 (20.7) |

| Electrochemotherapy | 4 (23.5)a | 0 | 4 (13.8) |

| Isolated limb perfusion | 2 (11.8)a | 9 (75.0) | 11 (37.9) |

| Intralesional therapy injection of IL-2 or IFNα | 3 (17.6)a | 0 | 3 (10.3) |

| Topical imiquimod | 1 (5.9)b | 0 | 1 (3.4) |

| Other | 1 (5.9)c | 0 | 1 (3.4) |

| Systemic therapy, N (%) | 21 (60.0) | 2 (6.5) | 23 (34.8) |

| IFNα | 12 (57.1) | 0 | 12 (52.2) |

| Pembrolizumab | 8 (38.1) | 2 (100) | 10 (43.5) |

| Ipilimumab | 8 (38.1) | 0 | 8 (34.8) |

| Chemotherapyd | 7 (33.3) | 0 | 7 (30.4) |

| IL-2 | 3 (14.3) | 0 | 3 (13.0) |

| Nivolumab | 3 (14.3) | 0 | 3 (13.0) |

| Dabrafenib | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Imatinib | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

| Ipilimumab/nivolumab | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

| Trametinib/dabrafenib | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

IFN interferon, IL interleukin, IQR interquartile range, T-VEC talimogene laherparepvec

aPrior treatment only in Germany

bPrior treatment only in Austria

cOther local therapy was “Chemoperfusion, left leg with melphalan” for a patient in Austria

dExamples of chemotherapies given included dacarbazine, temozolomide and taxanes

Approximately two-fifths of patients (43.9%) had received locoregional therapy prior to treatment with T-VEC. Radiation therapy was the most common locoregional therapy in Austria, Germany, and the UK (40.0% of patients). Electrochemotherapy and intralesional therapy injection of interleukin-2 or interferon-alfa only occurred in Germany. Isolated limb perfusion was the most common locoregional therapy in the Netherlands (29.0% of patients).

Prior systemic therapy had been received by 34.8% of patients and was more common in Austria, Germany, and the UK (60.0%) than in the Netherlands (6.5%). Patients in the Netherlands were previously treated with pembrolizumab or dabrafenib. The most common prior systemic therapies in Austria, Germany, and the UK were interferon-alfa, pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, and chemotherapy. Systemic treatments received prior to T-VEC are summarised in Supplementary Fig. S1a.

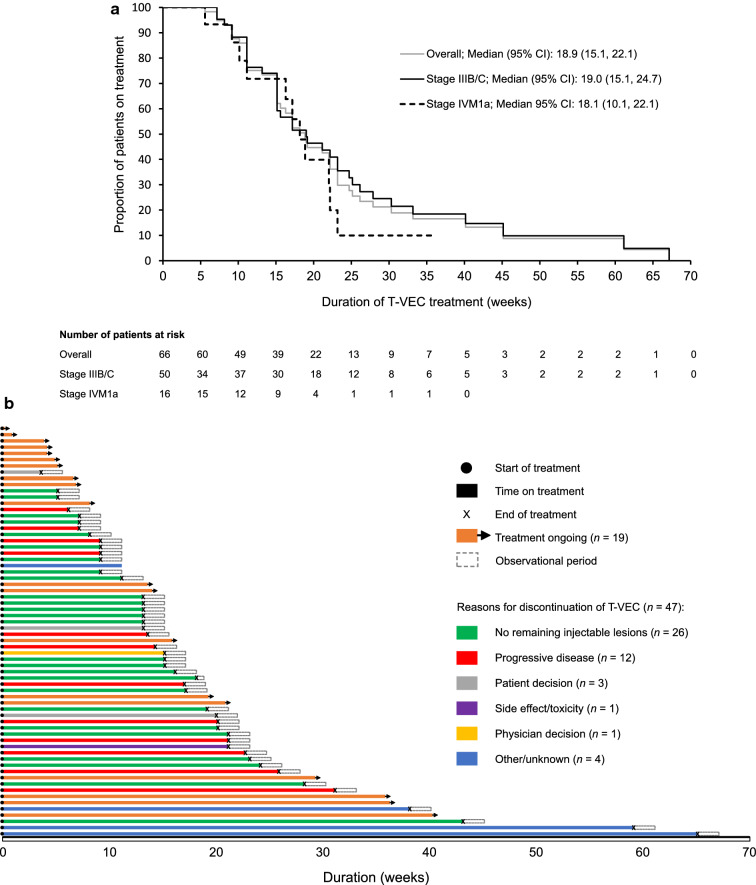

Treatment with T-VEC

Most patients received T-VEC as first-line therapy for unresectable disease (72.7%), but this percentage was higher for the Netherlands (93.5%) than for Austria, Germany, and the UK (54.3%; Table 3). Almost half of patients in Austria, Germany, and the UK received at least two lines of therapy, compared with only one-fifth of patients in the Netherlands. T-VEC and pembrolizumab were the most common second-line therapies. The median duration of treatment with T-VEC for all patients was 18.9 weeks according to Kaplan–Meier analysis and was similar for patients with stage IIIB/C versus stage IVM1a disease (19.0 vs 18.1 weeks; Fig. 2a). Treatment duration was longer in Austria, Germany, and the UK than in the Netherlands in patients with stage IIIB/C (24.7 vs 15.1 weeks) and IVM1a disease (18.9 vs 17.1 weeks) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Median treatment duration was longer for those who received T-VEC as second-line therapy (20.6 weeks) than for those who received it as first-line (18.1 weeks) or as third-line or greater (15.9 weeks) therapy (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Table 3.

Melanoma treatment by line of therapy

| Austria, Germany, UK (n = 35) n (%) |

Netherlands (n = 31) n (%) |

Total (N = 66) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| First-line | 35 (100) | 31 (100) | 66 (100) |

| T-VEC monotherapy | 19 (54.3) | 29 (93.5) | 48 (72.7) |

| Chemotherapya | 5 (14.3) | 0 | 5 (7.6) |

| Ipilimumab monotherapy | 4 (11.4) | 0 | 4 (6.1) |

| Pembrolizumab monotherapy | 2 (5.7) | 2 (6.5) | 4 (6.1) |

| Ipilimumab + nivolumab combination therapy | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| Trametinib + dabrafenib combination therapy | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| Interleukin-2 monotherapy | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| Other systemic therapyb | 2 (5.7) | 0 | 2 (3.0) |

| Second-line | 17 (48.6) | 6 (19.4) | 23 (34.8) |

| T-VEC monotherapy | 6 (35.3) | 1 (16.7) | 7 (30.4) |

| Pembrolizumab monotherapy | 4 (23.5) | 3 (50.0) | 7 (30.4) |

| Ipilimumab monotherapy | 3 (17.6) | 0 | 3 (13.0) |

| Ipilimumab + nivolumab combination therapy | 1 (5.9) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (8.7) |

| Nivolumab monotherapy | 2 (11.8) | 0 | 2 (8.7) |

| Chemotherapya | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

| Dabrafenib monotherapy | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (4.3) |

| Other systemic therapyc | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 2 (8.7) |

| Third-line | 12 (34.3) | 1 (3.2) | 13 (19.7) |

| T-VEC monotherapy | 6 (50.0) | 1 (100) | 7 (53.8) |

| Pembrolizumab monotherapy | 2 (16.7) | 0 | 2 (15.4) |

| Chemotherapya | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (7.7) |

| Ipilimumab + nivolumab combination therapy | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (7.7) |

| Interleukin-2 monotherapy | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (7.7) |

| Nivolumab monotherapy | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (7.7) |

| Fourth-line | 7 (20.0) | 0 | 7 (10.6) |

| T-VEC monotherapy | 2 (28.6) | 0 | 2 (28.6) |

| Chemotherapya | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 1 (14.3) |

| Vemurafenib + cobimetinib combination therapy | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 1 (14.3) |

| Pembrolizumab monotherapy | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 1 (14.3) |

| Imatinib monotherapy | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 1 (14.3) |

| Trametinib monotherapy | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 1 (14.3) |

| Fifth-line | 4 (11.4) | 0 | 4 (6.1) |

| T-VEC monotherapy | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 1 (25.0) |

| Chemotherapya | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 1 (25.0) |

| Trametinib + dabrafenib combination therapy | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 1 (25.0) |

| Ipilimumab monotherapy | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 1 (25.0) |

| Sixth-line | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (1.5) |

| Imatinib monotherapy | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) |

| T-VEC monotherapy | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (100) |

T-VEC talimogene laherparepvec

aExamples of chemotherapies given included dacarbazine, temozolomide, and taxanes

bOne patient received bevacizumab; the other participated in a clinical trial (NCT01844505)

cTwo patients participated in a clinical trial (NCT02625337)

Fig. 2.

Duration of treatment with T-VEC: a Kaplan–Meier analysis of time to T-VEC treatment discontinuation. b Swimmer plot showing time on T-VEC treatment until initiation of chart review. CI confidence interval, T-VEC talimogene laherparepvec

The median number of T-VEC administrations per patient was 7 (range 1–30), and the mean and median cumulative volumes injected per patient were 15.3 and 12.8 mL, respectively. For patients with ongoing treatment at the end of the study period, the mean and median were 11.1 and 9.0 mL; and the mean and median were 16.9 and 14.0 mL for those who discontinued. The median volume of the first dose (106 PFU/mL) was 2.0 mL (range 0.6–4.0), compared with 1.7 mL (range 0.5–4.0) for all subsequent doses (108 PFU/mL).

Two patients with stage IIIC melanoma were re-treated with T-VEC. Both patients discontinued their initial treatment as there were no remaining injectable lesions. The time interval between stopping and restarting was 147 days (4.8 months) in the first patient and 476 days (15.6 months) in the second patient.

Lesion Characteristics

Table 4 shows the characteristics of melanoma lesions at first administration of T-VEC. Of the 558 lesions detected, 50% were cutaneous, 44.6% were subcutaneous, and 2.9% were nodal. The number of lesions per patient ranged from 1 to 50, with a mean of 8.5 and median of 6.0. Nodal lesions had the largest diameter (median 9.5 mm), followed by subcutaneous (median 5.0 mm) and cutaneous lesions (median 3.0 mm). Cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions were found most frequently on the lower extremities (63.1% and 74.3%, respectively), while around two-thirds of nodal lesions were inguinal or axillary. Overall, 92.1% (514/558) of lesions were injected with T-VEC. This percentage was higher for cutaneous (97.8%) than for subcutaneous (87.1%) or nodal (81.3%) lesions.

Table 4.

Melanoma lesion characteristics at first administration of talimogene laherparepvec, at the lesion level and patient level

| Overall | Lesion levelb | Patient level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total lesions | Lesions injected with T-VEC | Lesions not injected with T-VEC | Total patients | Lesions injected with T-VEC | Lesions not injected with T-VEC | |

| (N = 558) | (N = 514) | (N = 44) | (N = 66) | (N = 66) | (N = 9) | |

| Cutaneous lesions, n (%)a | 279 (50.0) | 273 (53.1) | 6 (13.6) | 38 (57.6) | 38 (57.6) | 4 (44.4) |

| Head/neck | 6 (2.2) | 6 (2.2) | 0 | 2 (5.3) | 2 (5.3) | 0 |

| Trunk | 78 (28.0) | 77 (28.2) | 1 (16.7) | 10 (26.3) | 10 (26.3) | 1 (25.0) |

| Inguinal | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0 |

| Upper extremity | 18 (6.5) | 17 (6.2) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (13.2) | 4 (10.5) | 1 (25.0) |

| Lower extremity | 176 (63.1) | 172 (63.0) | 4 (66.7) | 27 (71.1) | 27 (71.1) | 2 (50.0) |

| Diameter of lesions (mm) | Number of lesions | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.6 (4.9) | 3.3 (–) | 4.6 (5.0) | 7.3 (6.7) | 7.2 (6.8) | 1.5 (1.0) |

| Median (IQR; range) | 3.0 (2, 5; 1–40) | 3.3 (–) | 3.0 (2, 5; 1–40) | 6.0 (2, 10; 1–30) | 5.5 (2, 10; 1–30) | 1.0 (1, 2; 1–3) |

| Subcutaneous lesions, n (%)a | 249 (44.6) | 217 (42.2) | 32 (72.7) | 35 (53.0) | 34 (51.5) | 4 (44.4) |

| Head/neck | 30 (12.0) | 30 (13.8) | 0 | 4 (11.4) | 4 (11.8) | 0 |

| Trunk | 26 (10.4) | 26 (12.0) | 0 | 3 (8.6) | 3 (8.8) | 0 |

| Inguinal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Upper extremity | 8 (3.2) | 8 (3.7) | 0 | 4 (11.4) | 4 (11.8) | 0 |

| Lower extremity | 185 (74.3) | 153 (70.5) | 32 (100) | 24 (68.6) | 23 (67.6) | 4 (100) |

| Diameter of lesions (mm) | Number of lesions | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.8 (8.2) | 6.9 (8.3) | 3.6 (3.3) | 7.1 (9.9) | 6.4 (7.4) | 8.0 (11.5) |

| Median (IQR; range) | 5 (3, 8; 1–60) | 5 (3, 8; 1–60) | 2.6 (1, 4.6; 1–10) | 3.0 (1, 8; 1–50) | 3.0 (1, 8; 1–27) | 3.0 (1, 15; 1–25) |

| Nodal lesions, n (%) a | 16 (2.9) | 13 (2.5) | 3 (6.8) | 6 (9.1) | 5 (7.6) | 2 (22.2) |

| Head/neck | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Axillary | 5 (31.3) | 4 (30.8) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Cervical | 1 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0 |

| Inguinal | 6 (37.5) | 4 (30.8) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Trunk | 1 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0 |

| Upper extremity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lower extremity | 2 (12.5) | 2 (15.4) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0 |

| Other | 1 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0 |

| Diameter of lesions (mm) | Number of lesions | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.7 (7.0) | 10.2 (7.0) | 18 (–) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.1) | 1.5 (0.7) |

| Median (IQR; range) | 9.5 (5, 17; 3–25) | 8.0 (5, 16.0; 3–25) | 18 (–) | 2.5 (2, 3; 1–5) | 3 (2, 3; 1–4) | 1.5 (1, 2; 1–2) |

IQR interquartile range, SD standard deviation, T-VEC talimogene laherparepvec

aSubjects can have lesions on multiple body sites

bNumber of subjects with evaluable data for lesion diameter

Clinical Outcomes

Overall, 19/66 (28.8%) patients were still receiving T-VEC at the end of the observation period (Fig. 2b). More than half of patients discontinued T-VEC treatment (26/47; 55.3%) because they had no remaining injectable lesions. Of these 26 patients, 22 (84.6%) had stage IIIB/C disease, 20 (76.9%) were from the Netherlands, 15 (57.7%) had an ECOG performance status of 0, 13 were BRAF mutation positive (from a total of 22 with known BRAF mutation status), 2 (7.7%) had baseline LDH > ULN, and 23 (88.5%) received T-VEC as first-line systemic therapy.

One-quarter of patients discontinued (12/47; 25.5%) because of progressive disease, and only one patient discontinued because of an AE or toxicity related to T-VEC. Seven patients developed distant metastasis, of whom five patients had one metastasis and two patients had two. The location of metastasis was the lung (n = 2), brain (n = 1), mesentery (n = 1), and thyroid (n = 1), and was not recorded in the patient charts in four cases. The median time to distant metastasis after initiation of treatment with T-VEC in these patients was 20.9 weeks (range 9.9–65 weeks).

The treatment histories of individual patients after T-VEC are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1b. Among the 11 patients who discontinued T-VEC treatment, the mean and median time to subsequent treatment were 6.4 and 5.4 months, respectively. Specifically, among patients who discontinued treatment because of progressive disease, mean and median time to subsequent treatment were 4.7 and 4.3 months, respectively, and ranged from 2.2 to 7.9 months. For patients who discontinued treatment because of no injectable lesions, the mean and median time to subsequent treatment were both 13.2 months (range 11.1–15.3 months).

Tolerability and Safety

Forty-seven patients (71.2%) experienced at least one AE of interest. Table 5 shows the events of interest occurring during T-VEC treatment. The most frequently reported events of interest were flu-like symptoms (36.4%), fatigue (21.2%), injection-site pain (19.7%), erythema (19.7%), rash/itch (16.7%), fever (12.1%), and nausea (10.6%). There were four physician-defined immune-mediated events, but only one event—vitiligo—appeared to be associated with T-VEC. One unconfirmed herpetic event was reported (see Table 5 footnote for further information). One patient discontinued T-VEC because of nausea. No deaths occurred during the study period.

Table 5.

Adverse events of interest observed during talimogene laherparepvec treatment

| Events of interesta | Austria, Germany, UK (n = 35) | Netherlands (n = 31) | Total (N = 66) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Administration-site conditions | 5 | 14.3 | 25 | 80.6 | 30 | 45.5 |

| Burning sensation | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 12.9 | 4 | 6.1 |

| Erythema | 1 | 2.9 | 12 | 38.7 | 13 | 19.7 |

| Injection-site complications | 3 | 8.6 | 3 | 9.7 | 6 | 9.1 |

| Injection-site pain | 2 | 5.7b | 11 | 35.5 | 13 | 19.7 |

| Pruritus left leg | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Rash/itch | 0 | 0 | 11 | 35.5 | 11 | 16.7 |

| Wateriness left shank | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 4 | 11.4 | 8 | 25.8 | 12 | 18.2 |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12.9 | 4 | 6.1 |

| Diarrhoea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Nausea | 4 | 11.4 | 3 | 9.7 | 7 | 10.6 |

| Vomiting | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 |

| General disorders | 5 | 14.3 | 27 | 87.1 | 32 | 48.5 |

| Ague (fever and chills) | 2 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3.0 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Dyspnoea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 14 | 45.2 | 14 | 21.2 |

| Fever | 3 | 8.6 | 5 | 16.1 | 8 | 12.1 |

| Flu-like symptoms | 0 | 0 | 24 | 77.4 | 24 | 36.4 |

| Hot flush/sweating | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 3.2 | 2 | 3.0 |

| Herpetic events | 0 | 0 | 1c | 3.2 | 1c | 1.5 |

| Physician-defined immune-mediated events | 3 | 8.6d | 1 | 3.2 | 4 | 6.1 |

| Other | 2 | 5.7 | 9 | 29.0 | 11 | 16.7 |

| Airway infection | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Arthralgia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Oedema right ankle | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Headache | 1 | 2.9 | 5 | 16.1 | 6 | 9.1 |

| Increase in liver enzymes | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Muscle ache | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6.5 | 2 | 3.0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Pain in joints | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Urine incontinence | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.5 |

aSubjects with multiple adverse events are only reported once per event term

bPain left foot, pain left shank

cThe details of this event are as follows: The time from the first talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) dose to the herpetic event was 176 days. The event occurred 4–5 days after an administration of T-VEC. The patient suffered from local redness, vesicles on trunk, and flu-like illness. There was no itching or fever. A physical examination (1.5 weeks after the event) showed no more vesicles, therefore no diagnostics (polymerase chain reaction) could be carried out. This event was recorded by the Amgen safety department as an unconfirmed herpetic event because the symptoms were suggestive, but not confirmed

dPhysician-defined immune-mediated events were eczema, increased 2-deoxy-2-fluoro-d-glucose (FDG) uptake in distant nodes without progression, and vitiligo. Only one event (vitiligo) appeared to be associated with T-VEC

Discussion

This retrospective study is, to our knowledge, the largest and the first multinational real-world analysis of T-VEC usage in Europe. The data support the findings of the phase 3 randomised OPTiM study, which concluded that T-VEC was effective and well tolerated [8].

The findings suggest that T-VEC is used in the real-world setting in patients with a lower disease burden than in OPTiM [8]. Although T-VEC is approved in Europe for patients with stage IIIB/C–IVM1a recurrent melanoma, 71.2% of patients treated with T-VEC in the current real-world study had stage IIIB/C disease (vs 52.6% in OPTiM [8]). A lower percentage of patients in the current study had lymph node lesions than in the OPTiM study [8] (9.1% vs 42.9%, respectively) and the overall median number of lesions per T-VEC-treated patient was also lower (8.5 in our study vs 10 in OPTiM [20]). These differences may again indicate a lower disease burden among patients who received T-VEC in the real-world setting. In our study, the median volume of T-VEC administered per visit was also lower than in OPTiM (2 vs 3 mL), and the median duration of T-VEC treatment was shorter (18.9 vs 25.7 weeks).

It is possible that the differences summarised above were driven by a tendency for patients in the Netherlands to initiate T-VEC treatment at an earlier disease stage compared both to the patients in the OPTiM study and to real-world patients from Austria, Germany, and the UK in our study. Overall, 96.8% of patients treated with T-VEC in the Netherlands had early metastatic stage IIIB/C disease, and 93.5% received T-VEC as first-line therapy (vs 48.6% and 54.3%, respectively, in Austria, Germany, and the UK). Additionally, we found that the interval between initial diagnosis and first T-VEC administration was shorter in the Netherlands than in the other three countries. Furthermore, patients in the Netherlands received fewer excisions for recurrence before commencing T-VEC. Overall, the median duration of treatment with T-VEC was shorter in the Netherlands than in Austria, Germany, and the UK (15.1 vs 23.1 weeks). As well as reflecting differences in initial disease burden, this may also partly reflect differences in treatment practices between medical and surgical oncology settings.

Although the current study did not include formal evaluation of treatment effectiveness, a greater proportion of patients in the Netherlands discontinued T-VEC before the end of the study period because they had no remaining injectable lesions compared with the other three countries (64.5% vs 17.1%, respectively). Absence of any remaining injectable lesions may be considered a proxy for a complete response [21]. This could be due to the high proportion of patients in the Netherlands with early metastatic disease. Additionally, a lower initial disease burden among T-VEC recipients in the Netherlands may have resulted in a faster clinical response in this group, and thus shorter treatment duration. Another factor that may have contributed to the improved responses observed in patients in the Netherlands is BRAF status. Almost 50% of T-VEC-treated patients in the Netherlands had a BRAF mutation, compared with only one-quarter of patients in the other three countries.

Six retrospective studies have previously examined real-world use of T-VEC for the treatment of unresectable stage IIIB–IVM1c melanoma in the USA [11–15] and the Netherlands [16]. Five of the retrospective studies reported ORRs higher than the 26.4% reported in OPTiM (40.7% [11], 47.5% [12], 56.5% [13], 57% [14], and 88.5% [16]). Compared with OPTiM, these studies also included higher proportions of patients with stage IIIB/C versus stage IV disease. In the study from the Netherlands, for example, in which 16/26 patients (61.5%) achieved a complete response and 7/26 (26.9%) a partial response, all patients had stage IIIB/C disease [16]. Overall, the results of these studies and this current study suggest that patients with more advanced disease can benefit from T-VEC, but that the efficacy of T-VEC monotherapy is optimised when initiated early in the treatment journey, and particularly in patients with unresectable stage IIIB/C melanoma.

As in OPTiM, and consistent with previous real-world reports [11–15], T-VEC was well tolerated in the current study. No unexpected AEs of interest were observed. The most frequently occurring AEs were flu-like symptoms. Only one patient discontinued treatment because of an AE or toxicity related to T-VEC.

A larger proportion of patients in this study had received systemic therapy, particularly immunotherapy, prior to T-VEC than in OPTiM (34.8% vs 6%). This is not surprising, as many of these therapies were not available when OPTiM was conducted (2009–2011). Prior treatment with targeted therapies and immunotherapies does not appear to reduce the response to T-VEC [16]. Indeed, T-VEC is being investigated in combination with targeted therapies and immunotherapies, with early results suggesting that such combinations may improve clinical outcomes. A phase 2 randomised study found superior ORR and complete response rates with T-VEC plus ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone [22], while the phase 1b MASTERKEY-265 study suggested that T-VEC may enhance responsiveness to checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab [23]. In the phase 1b MASTERKEY-265 study, T-VEC plus pembrolizumab resulted in an ORR of 62%, with a confirmed complete response rate of 33%, in patients with unresectable stage IIIB/C–IV melanoma [23]. The phase 3 part of MASTERKEY-265 is ongoing.

By documenting a wide range of clinical variables, this study provides insights into T-VEC usage in routine clinical practice in European countries that utilise this therapy in different settings. Limitations of the study design include the absence of formal efficacy assessment, the cessation of follow-up while T-VEC therapy was ongoing, and the potential for selection bias when identifying patients for inclusion. Although steps were taken to ensure that complete and accurate information was obtained from the medical charts, we cannot fully exclude the potential for information bias if data were missing. The patients in this study were all treated within the first 3 years of EU marketing authorisation of T-VEC. While the data provide a good indication of early usage, treatment practices might evolve over time with increasing cumulative clinical experience. It is also possible that treatment/management practices of “early adopter” physicians differ from those of other physicians.

Conclusions

This is the first comprehensive multinational evaluation of the use of T-VEC to treat unresectable stage IIIB/C-IVM1a melanoma in real-world clinical practice in Europe. The results indicate that the effectiveness of T-VEC monotherapy is optimised when initiated early in the treatment paradigm, particularly in patients with unresectable stage IIIB/C disease. Favourable tolerability was observed, with only one patient discontinuing treatment because of an AE or toxicity.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for providing consent to use their data for the study.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and the journal’s rapid service and open access fees were funded by Amgen, Inc. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing support (including development of a draft outline and subsequent drafts in consultation with the authors, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copy-editing, fact-checking, and referencing) was provided by Emma McConnell and Ryan Woodrow from Aspire Scientific Ltd (Bollington, UK), and funded by Amgen, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

A.C.J. van Akkooi declares advisory board and consultancy honoraria (all paid to institute) from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD)-Merck, Merck-Pfizer, Novartis, Sanofi, and 4SC; and research grants (all paid to institute) from Amgen, BMS, Merck-Pfizer, and Novartis. S. Haferkamp has received research grants from BMS and Novartis; and consulting fees from Amgen, BMS, and Novartis. S. Papa has received honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), MSD, and Roche; advisory role fees from BMS, GSK, MSD, and Zelluna; and research funding from GSK. V. Franke declares advisory board and consultancy honoraria and a research grant received from Amgen. A. Pinter has received research grants from AbbVie; and consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Leo, and Novartis. C. Weishaupt has received consulting/advisory fees from Amgen, BMS, GSK, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, and Sanofi; travel, accommodations, or expenses from Amgen, BMS, Novartis, and Pierre Fabre; honoraria from BMS, CureVac, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, and Sanofi; and research funding from BMS. M.A. Huber has received consulting or advisory board fees from MSD and Pierre Fabre; and travel, accommodations, or expenses from MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. C. Loquai has received consulting fees or other remuneration from Amgen, BMS, Leo, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Roche. E. Richtig has received honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, and Sanofi; consulting/advisory fees from Amgen, Bayer, BMS, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, and Sanofi; speakers’ bureau fees from Amgen, BMS, MSD, Merck, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi; research funding from Amgen, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Roche; and travel, accommodations, or expenses from Amgen, BMS, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, and Sanofi. P. Gokani, K. Öhrling, and K.S. Louie are employees and shareholders of Amgen. P. Mohr has received consulting/advisory fees from Amgen, BMS, GSK, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, and Sanofi; speakers’ bureau fees from Amgen, BMS, MSD, Novartis, and Roche; travel, accommodations, or expenses from Amgen, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Roche; honoraria from Amgen, BMS, GSK, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche/Genentech, and Sanofi; and research funding from BMS (institution) and MSD (institution).

Compliance With Ethics Guidelines

This study was performed in accordance with the standards of the institutional ethic committees and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Approval was obtained from institutional ethics committees and review boards from all institutions (Supplementary Table S1), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Data Availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.European Medicines Agency. Imlygic summary of product characteristics. 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002771/WC500201079.pdf. Accessed 14 Aug 2020

- 2.Liu BL, Robinson M, Han ZQ, et al. ICP34.5 deleted herpes simplex virus with enhanced oncolytic, immune stimulating, and anti-tumour properties. Gene Ther. 2003;10:292–303. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Moesta AK, Cooke K, Piasecki J, et al. Local delivery of OncoVEX(mGM-CSF) generates systemic antitumor immune responses enhanced by cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6190–6202. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman HL, Kim DW, DeRaffele G, Mitcham J, Coffin RS, Kim-Schulze S. Local and distant immunity induced by intralesional vaccination with an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF in patients with stage IIIc and IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:718–730. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuhara H, Todo T. Oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 1 and host immune responses. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:149–155. doi: 10.2174/156800907780058907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gogas H, Samoylenko I, Schadendorf D, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) treatment increases intratumoral effector T-cell and natural killer (NK) cell density in noninjected tumors in patients (pts) with stage IIIB-IVM1c melanoma: evidence for systemic effects in a phase II, single-arm study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:viii443. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy289.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andtbacka RH, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2780–2788. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrington KJ, Andtbacka RH, Collichio F, et al. Efficacy and safety of talimogene laherparepvec versus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in patients with stage IIIB/C and IVM1a melanoma: subanalysis of the phase III OPTiM trial. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:7081–7093. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S115245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA. Imlygic prescribing information. 2015. https://www.fda.gov/media/94129/download. Accessed 8 Oct 2020.

- 10.Kennedy-Martin T, Curtis S, Faries D, Robinson S, Johnston J. A literature review on the representativeness of randomized controlled trial samples and implications for the external validity of trial results. Trials. 2015;16:495. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masoud SJ, Hu JB, Beasley GM, Stewart JH 4th, Mosca PJ. Efficacy of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) therapy in patients with in-transit melanoma metastasis decreases with increasing lesion size. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:4633–4641. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou AY, Wang DY, McKee S, et al. Correlates of response and outcomes with talimogene laherperpvec. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:558–564. doi: 10.1002/jso.25601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez MC, Miura JT, Naqvi SMH, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec (TVEC) for the treatment of advanced melanoma: a single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3960–3965. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6803-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louie RJ, Perez MC, Jajja MR, et al. Real-world outcomes of talimogene laherparepvec therapy: a multi-institutional experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228:644–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez MC, Zager JS, Amatruda T, et al. Observational study of talimogene laherparepvec use for melanoma in clinical practice in the United States (COSMUS-1) Melanoma Manag. 2019;6:MMT19. doi: 10.2217/mmt-2019-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franke V, Berger DMS, Klop WMC, et al. High response rates for T-VEC in early metastatic melanoma (stage IIIB/C-IVM1a) Int J Cancer. 2019;145:974–978. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoeller C, Ressler J, Karasek M, et al. Real life use of talimogene laherparepvec in melanoma in centers in Austria and Switzerland. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(Suppl. 5):v548–v549. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz255.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohr P, Haferkamp S, Pinter A, et al. Real-world use of talimogene laherparepvec in German patients with stage IIIB to IVM1a melanoma: a retrospective chart review and physician survey. Adv Ther. 2019;36:101–117. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0850-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Joint Committee on Cancer . Cancer staging manual. 7. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andtbacka RH, Ross M, Puzanov I, et al. Patterns of clinical response with talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) in patients with melanoma treated in the OPTiM phase III clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:4169–4177. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5286-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. WHO handbook for reporting results of cancer treatment. 1979. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/37200/WHO_OFFSET_48.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 14 Aug 2020

- 22.Chesney J, Puzanov I, Collichio F, et al. Randomized, open-label phase II study evaluating the efficacy and safety of talimogene laherparepvec in combination with ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced, unresectable melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1658–1667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribas A, Dummer R, Puzanov I, et al. Oncolytic virotherapy promotes intratumoral T cell infiltration and improves anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;170:1109–19.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.