Abstract

Background:

Behavioral economic theory predicts decisions to drink are cost benefit analyses, and heavy episodic drinking occurs when benefits outweigh costs. Social interaction is a known benefit associated with alcohol use. Although heavy drinking is typically considered more likely during more social drinking events, people who drink heavily in isolation tend to report greater severity of use. This study explicitly disaggregates between-person and within-person effects of sociality on heavy episodic drinking and examines behavioral economic moderators.

Methods:

We used day-level survey data over an 18-week period in a community adult sample recruited through crowdsourcing (mTurk; N=223). Behavioral economic indices were examined to determine if macro person-level variables (alcohol demand, delay discounting, proportionate alcohol-related reinforcement [R-ratio]) interact with event-level social context to predict heavy drinking episodes.

Results:

Mixed effect models indicated significant between-person and within-person social context associations. Specifically, people with a higher proportion of total drinking occasions in social contexts had decreased odds of heavy drinking, whereas being in a social context for a specific drinking occasion was associated with increased odds of heavy drinking. Person-level R-Ratio, demand elasticity, and breakpoint variables interacted with social context to predict heavy episodic drinking, such that the event-level social context association was stronger when R-Ratios, alcohol price insensitivity, and demand breakpoints were high.

Conclusions:

These results demonstrate an ecological fallacy, in which the size and direction of effects were divergent at different levels of analysis, and highlight the potential for merging behavioral economic variables with proximal contextual effects to predict heavy drinking.

Keywords: Alcohol, Behavioral Economics, Decision-Making, Demand, Discounting, Social

1. Introduction

Alcohol use is common in the United States, with over 50% of adults reporting past 30 day alcohol consumption (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020). Although most people drink in moderation, some engage in heavy drinking episodes, consuming 4/5 drinks on a single occasion for women/men. Heavy episodic drinking can lead to significant acute (e.g., hangovers, blackout) and chronic (e.g., academic/occupational impairment, alcohol-related cirrhosis) consequences (Jennison, 2004; Tapper and Parikh, 2018) and costs the United States billions of dollars each year (Sacks et al., 2015). It is important to understand why people continue to drink despite negative consequences and the contexts in which heavy drinking is most prominent to optimize prevention and treatment efforts.

Behavioral economics incorporates principles of microeconomics with operant psychology (i.e., the “economics of behavior”; Hursh and Roma, 2013) to explain choice behavior, providing a framework for conceptualizing persistent alcohol consumption despite negative consequences. From this perspective, decisions are cost/benefit analyses, and choices are made to maximize benefits and minimize costs. Preference for a substance varies relative to the availability of and constraints on access to alternatives in the choice context. Further, costs and benefits (defined broadly) are distributed unevenly over time, so utility maximization depends critically upon the individual’s temporal frame of reference for calculating value (Vuchinich, 1995; Vuchinich and Heather, 2003). Additionally, although behavioral economics emphasizes cost/benefit decision making, it does not assume that these choices or calculations are always deliberate or that outcomes are “rational”, because utility may be maximized under varying conditions of reference (e.g., over varying temporal frames). From this perspective, persistent problematic substance use is a reinforcer pathology in which drugs, potent immediate reinforcers with delayed costs, are persistently overvalued and chosen relative to alternative substance-free reinforcers with delayed benefits and immediate costs (Bickel et al., 2014).

Critically, behavioral economics emphasizes that harmful substance use is a pattern or collection of persistent choice for the substance over alternatives, rather than any discrete event (Vuchinich, 1995). Behavioral economics research commonly uses indices that aggregate decision making across varying choice contexts to characterize molar patterns. In cross-sectional studies, these trait-based measures of the relative value of alcohol, such as reinforcement surveys and alcohol purchase tasks, demonstrate consistent associations with retrospective drinking behavior and problems (Acuff et al., 2019; MacKillop et al., 2011; Zvorsky et al., 2019). Behavioral economics incorporates economic principles with traditional operant decision-making to explain how individually-computed benefits of substance use can outweigh costs and considers the collection of these choice outcomes greater than any discrete choice event.

Social interactions are one major benefit underlying alcohol and other substance use. Preclinical animal research has consistently documented the relevance of social context and reward in drug self-administration and choice (see reviews in Bardo et al., 2013; Heilig et al., 2016; Strickland and Smith, 2014). For example, presence of a conspecific during drug self-administration in rodents can facilitate acquisition, maintenance, and reinstatement with this effect at least partly dependent on the substance-related history of that peer (Hofford et al., 2020; Smith, 2012; Smith et al., 2014). On the other hand, social reward (e.g., contingent access to other rodents) can act as a potent alternative reinforcer that reduces drug choice within discrete choice contexts, with preference for this alternative diminished when social reward is devalued, for example, by delay (Venniro and Shaham, 2020; Venniro et al., 2018). This preclinical animal work points to two key conclusions: (1) social context (i.e., whether one is with or not with others) is relevant to substance-related decision-making and (2) social interactions can act as either risk or protective factors depending on their functional role in the choice environment.

Evidence from human participants signify similar trends in the relation between social context and substance use. Alcohol, specifically, increases subjective feelings and objective indicators of social interaction and bonding (Sayette et al., 2012), and individuals reporting a greater number of heavy drinking friends, in addition to having friends present during a specific drinking episode, also report greater heavy drinking (Murphy et al., 2006; Thrul and Kuntsche, 2015) and motivation to drink (Acuff et al., 2020b; Acuff et al., 2020c). Solitary drinking episodes, however, are also generally associated with increased alcohol-related problems, in addition to an increased likelihood of suicidal ideation, depression, and social anxiety (Bilevicius et al., 2018; Gonzalez et al., 2009; Keough et al., 2018). Thus, although heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems are more likely during more highly socially interactive drinking events, people who drink heavily in isolation generally exhibit greater severity of use. A critical gap in existing literature is an empirical disaggregation of between-person (i.e., person-aggregated) and within-person (i.e., event-specific) effects of social context on drug-taking events, broadly, and heavy drinking episodes, specifically.

Relevant to this role of social context, recent theoretical advances combining behavioral economics with values-based decision making contend that accounting for contextual variables in discrete choice contexts can enhance molar accounts of decision making, increasing overall predictive utility (Field et al., 2020). In other words, those who overvalue alcohol relative to alternative, long-term rewards, will be more likely to report heavy drinking episodes. However, the social constraints of any given drinking context will impact the momentary cost/benefit ratio of alcohol-related decision making for those people.

This analysis had two primary goals: (1) to disaggregate the between- and within-person effects of the social context on heavy episodic drinking; and (2) to examine the interaction between molar, behavioral economic indices of alcohol-related decision making with the proximal social context of any discrete drinking event. We accomplish these goals using day-level survey data over 18 weeks, collected from alcohol-using adults (N = 223). This sample comprised a heterogenous group of people reporting alcohol use (i.e., weekly alcohol consumption) spanning low/subclinical to high/clinical problematic consumption to evaluate individual patterns with sufficient variability to detect differences in use. This analysis attempts to delineate the role of the social context as a determinant of heavy episodic drinking and contributes to theoretical model development by combining molar characterizations of alcohol-related decision making with contextual social variables to enhance predictive utility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Procedures

Participants were recruited using the crowdsourcing resource Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk) from June to November 2017. Crowdsourcing has been successfully used in behavioral and addiction science to recruit geographically diverse samples for remotely conducted studies (Mellis and Bickel, 2020; Strickland and Stoops, 2019). Eligible participants recruited from mTurk were: 1) age 21 or older, 2) had an Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) score ≥1 (Saunders et al., 1993), 3) self-reported alcohol use in the week prior to screening, and 4) willingness to complete an 18-week study. Qualifying participants completed a baseline survey that included behavioral economic measures. A longitudinal study phase followed consisting of 18 weekly surveys in which participants recorded past week alcohol use by day. The average response rate during this period was 73% (range: 64.1%-86.8% each week). Two analyses have previously been published from this study (Strickland et al., 2019; Strickland and Stoops, 2018). These studies focused on the feasibility, acceptability, and validity of longitudinal data collection on mTurk (Strickland and Stoops, 2018) and the test-retest reliability of and trait-level prediction by behavioral economic variables (Strickland et al., 2019). The current study reports on previously unanalyzed proximal variables (i.e., social context) and cross-level interactions with trait behavioral economic measures. The University of Kentucky IRB approved all procedures and informed consent obtained prior to participation.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Alcohol Use

Participants completed weekly assessments of past week daily alcohol use during the longitudinal phase of data collection. Participants were asked to report the number of standard drinks consumed by alcohol type (e.g., 12 oz. beers, 1.5 oz. liquor) on each day during the past week. Participants were also asked if drinking occurred in a social context or not (i.e., “did you drink with other people?”). Participants were asked to consider drinking throughout the entire day when answering this social context question. Heavy drinking was defined using NIAAA guidelines of ≥5/≥4 drinks/day for men/women (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse Alcoholism, 2007).

2.2.2. Proportionate Alcohol-Related Reinforcement

The Reinforcement Survey Schedule-Alcohol Use Version was used to evaluate proportionate alcohol-related reinforcement (Morris et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2005; see review in Acuff et al., 2019). Participants rated frequency and enjoyability of activities over a 30-day period (e.g., go out to eat) when (1) not drinking alcohol and (2) drinking alcohol. Frequency and enjoyability ratings were multiplied for each item to create a cross-product score. The primary measure was the R-Ratio reflecting the ratio of total alcohol-related reinforcement to total reinforcement (i.e., alcohol-free plus alcohol-related reinforcement).

2.2.3. Hypothetical Delay Discounting

Delay discounting for hypothetical monetary outcomes was determined using a 5-trial adjusting delay task (Koffarnus and Bickel, 2014). Prior studies have validated this 5-choice task against traditional adjusting amount discounting tasks (Cox and Dallery, 2016; Koffarnus and Bickel, 2014). Participants selected between $500 available immediately and $1000 at a delay. The first choice was at three-weeks delay, which then adjusted down (shorter delay following immediate choice) or up (longer delay following delayed choice) depending on each trial choice. An effective delay 50% (ED50) was determined following five titrated choices. The primary outcome was delay discounting rates calculated as the inverse of ED50. Delay discounting rates were log transformed for normality.

2.2.4. Behavioral Economic Demand

Hypothetical purchase tasks were used to evaluate behavioral economic demand for alcohol (Murphy and MacKillop, 2006). Prior work has validated the alcohol purchase task for temporal reliability, stimulus-selectivity, and construct validity as well as correspondence with incentivized rewards (e.g., Acuff and Murphy, 2017; Amlung and MacKillop, 2015; Strickland and Stoops, 2017). Participants were asked to imagine a typical day over the last month when they used alcohol and provided a standard instructional set (i.e., closed economy, no prior alcohol consumption; Supplemental Materials). Instruction checks were also included which participants had to answer correctly to proceed. Participants were instructed to report the number of standard alcohol drinks they would consume at 13 monetary increments ranging from $0.00 [free] to $11/unit, presented sequentially.

Price intensity and elasticity were generated using the exponentiated demand equation (Koffarnus et al., 2015):

where Q = consumption; Q0 = derived demand intensity; k = a constant related to consumption range (a priori set to 2); C = commodity price; and α = derived demand elasticity. Demand intensity refers to the consumption of a commodity at a unit price of zero (i.e., free). Demand elasticity reflects sensitivity of consumption to changes in price. Additional observed metrics were computed including Omax, (maximum expenditure), Pmax (observed price at maximum expenditure), and breakpoint (last price prior to suppressed consumption). Demand intensity was log transformed and demand elasticity and Omax square-root transformed to improve normality.

2.3. Data Analysis

Thirty of the 307 participants completing the baseline survey failed one or more data quality checks, did not provide any assessments in the longitudinal phase, and/or did not report drinking alcohol in the longitudinal phase and were removed from data analysis (n = 277). Purchase task data were evaluated for systematicity using standard criteria (Stein et al., 2015). Fifty participants provided non-systematic data either violating these criteria (n = 19) or reporting zero consumption at all prices (n = 31), and four participants did not complete the alcohol purchase task. This resulted in a final sample of 223 participants with systematic study and alcohol purchase task data. Analyses focused on this sample given primary hypotheses related to behavioral economic demand. As reported previously (Strickland et al., 2019), comparisons between individuals included and excluded did not reveal significant differences in demographics, alcohol use, discounting rates, or R-Ratio scores suggesting that the sample characteristics were not compromised by removal.

Generalized linear mixed models were used to evaluate the association of social context with heavy drinking on drinking days. Generalized linear mixed models allowed for the incorporation of the repeated measure design and disaggregation of the between-subject and within-subject level social context. Specifically, the association of social context with heavy drinking could reflect 1) the aggregated proportion of drinking occurring in a social context (between-subject) and/or 2) the specific daily context of social relative to non-social drinking (within-subject). These non-mutually exclusive associations were included in models using a person-mean centering approach (Wang and Maxwell, 2015). In a simplified model specification this person-mean centering takes the form:

where i represents the individual subject and p represents the day-level episode. This specification includes a parameter reflecting the effect of the person-mean value of social context averaging over drinking episodes (i.e., γ01; the between-subject effect) as well as a parameter reflecting the effect of the day-specific context (i.e., γ10; the within-subject effect) and μ01 as the between person residual for γ00 (i.e., random effect term).

Models were first tested without behavioral economic moderators to determine the between-person and within-person social context associations. Models were then tested including interactions between behavioral economic variables and the within-person social context parameter to determine the interaction between molar behavioral economic operationalizations and the molecular contextual variable. Outliers for all behavioral economic variables were identified and winsorized for values 1.5 times the interquartile range outside the 1st/3rd quartile.1 Interaction models were tested separately; however, a post-hoc model was tested including all significant cross-level interactions. Continuous variables were mean centered to improve interpretation. Predicted probabilities of heavy drinking were plotted using model estimates for significant interactions to facilitate interpretation. All analyses were conducted using R (V4.0.3) with the lme4 packages (Bates et al., 2014).

3. Results

3.1. Participants and Study Records

Table 1 contains demographic and alcohol use variables for the sample. Approximately half of participants were female and the average age was 35.2 years old. Participants reported an average of 8.8 standard drinks/week and 3 drinking days/week with the majority reporting one or more heavy drinking day (75.8%).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Behavioral Economic Variables (N = 223)

| Mean (SD)/% | IQR | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 35.2 (10.5) | 27 to 41 |

| Male | 47.1% | |

| White | 83.0% | |

| College | 68.6% | |

| Married/In a Relationship | 56.1% | |

| Alcohol Use | ||

| Drinks/Weeks | 8.8 (9.3) | 3 to 12 |

| Days/Week | 3.0 (2.0) | 2 to 4 |

| Drinks/Occasion | 3.1 (2.0) | 2 to 4 |

| AUDIT | 10.3 (7.5) | 4 to 14 |

| Behavioral Economic Variables | ||

| R-Ratio | 0.36 (0.16) | 0.25 to 0.49 |

| Delay Discounting (k) [log] | −2.4 | −2.7 to −1.9 |

| Demand Intensity (Q0) [median] | 5.4 | 3.3 to 8.9 |

| Demand Elasticity (α) [median] | 0.011 | 0.006 to 0.028 |

| Pmax | $4.3 (3.2) | $2 to $6 |

| Omax | $10 | $5 to $16 |

| Breakpoint | $5.9 (3.8) | $3 to $11 |

Note. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; k = discounting rates; IQR = interquartile range. Demand intensity, elasticity, and Omax presented as median values given significant variable skew that was corrected in analyses by transformation.

A total of 8852 drinking days were recorded of which 2903 (32.8%) were heavy drinking days. Participants recorded an average of 39.7 drinking days (median = 28) and 13.0 heavy drinking days (median = 4). The slight majority of all drinking days involved social drinking (n = 4918; 55.6%) with roughly equal percentages of heavy drinking occurring on days with (33.2%) and without (32.3%) social drinking.

3.2. Social Context Drinking: Between and Within-Person Associations

Social context and heavy drinking were evaluated for between-person associations (i.e., mean proportion of drinking days involving social drinking) and within-person associations (i.e., day specific differences in social context). This mixed effect model indicated significant social context associations for between-person (OR = 0.25 [0.07, 0.79], p = .015) and within-person (OR = 4.18 [3.51, 5.00], p < .001) parameters. These associations, however, were in opposing directions. Specifically, individuals with a higher overall proportion of social context drinking had decreased odds of heavy drinking (between-person association), whereas during any given day a social context for drinking was associated with increased odds of heavy drinking (within-person association).

The size, sign, and magnitude of these associations remained when controlling for weekend versus weekday drinking in the model (Social-Between: OR = 0.20 [0.05, 0.66], p = .007; Social-Within: OR = 3.76 [3.15, 4.51], p < .001). Given that solitary drinking is associated with alcohol use disorder, we considered that the between-subject results may reflect drinking severity, and thus examined AUDIT as a covariate. Controlling for the AUDIT did not impact the within-person association (OR = 4.19 [3.52, 4.99], p <.001) whereas the between-subject social context association was no longer significant (OR = 1.27 [0.07, 0.79], p = .63). The interaction of within-person social context and AUDIT scores was not significant indicating that AUDIT was not a significant moderator (OR = 0.98 [0.96, 1.01], p = .21).

Interactions with demographic variables indicated no significant moderation by age (p = .67), race (p = .54), education (p = .70), or relationship status (p = .07). A significant interaction with gender was observed (OR = 1.56 [1.10, 2.20], p = .012) indicating that the within-person effect of social context was larger for men than women (Supplemental Figure 1).2

3.3. Behavioral Economic Moderators of Social Context Heavy Drinking

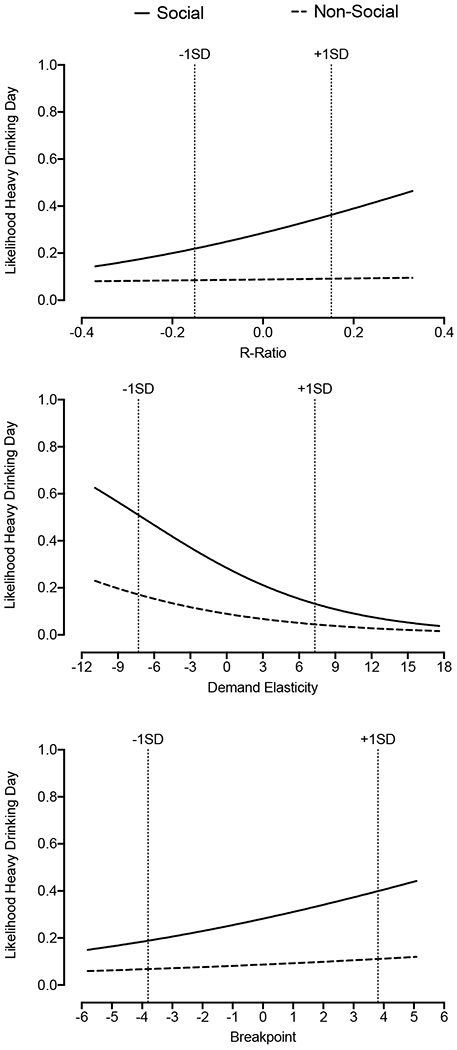

Table 2 contains a summary of the mixed effect models testing interactions between behavioral economic variables and the within-person effect of social context. Significant interactions were observed for R-Ratio (OR = 8.03 [2.74, 23.58], p < .001), demand elasticity (OR = 0.97 [0.95, 1.00], p = .023), and breakpoint (OR = 1.07 [1.02, 1.12], p = .005). These effects remained significant in models controlling for AUDIT scores (Table 2 bottom panels). Inclusion of all three significant interactions in a single model found that the R-Ratio interaction remained significant (p = .001) while the elasticity and breakpoint interactions were not significant (p values > .20).

Table 2.

Odds Ratio Estimates for Generalized Mixed Effect Models

| Null | R-Ratio | k | Q0 | α | Pmax | Omax | BP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | ||||||||

| Person-Level | ||||||||

| Social Context (Person Mean) | 0.25* | 0.30* | 0.30* | 0.84 | 0.35 | 0.24* | 0.41 | 0.26* |

| Behavioral Economic | - | 4.12 | 1.67* | 69.31*** | 0.89*** | 1.35 | 1.95*** | 1.11* |

| Event-Level | ||||||||

| Social Context (Day) | 4.18*** | 4.13*** | 4.35*** | 4.26*** | 4.04*** | 3.83*** | 3.90*** | 4.12*** |

| Social Context (Day) * Behavioral Economic | - | 8.03*** | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.97* | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.07** |

| AUDIT-Adjusted | ||||||||

| Person-Level | ||||||||

| AUDIT | 1.27*** | 1.25*** | 1.24*** | 1.18*** | 1.22*** | 1.24*** | 1.20*** | 1.24*** |

| Social Context (Person Mean) | 1.24 | 1.10 | 1.42 | 1.76 | 1.34 | 1.27*** | 1.28*** | 1.25 |

| BE Variable | - | 0.28 | 1.36 | 11.61*** | 0.94** | 0.97*** | 1.38*** | 1.04 |

| Event-Level | ||||||||

| Social Context (Day) | 4.19*** | 4.13*** | 4.36*** | 4.24*** | 4.04*** | 3.75*** | 3.88*** | 4.13*** |

| Social Context (Day) * BE Variable | - | 7.87*** | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.97* | 1.06 | 1.02 | 1.07** |

Note. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; k = delay discounting rates; Q0 = Demand Intensity; α = Demand Elasticity. All values represent adjusted odds ratios [OR]. The estimates in the row labeled “BE variable” refer to the specific behavioral economic variable labeled in each column corresponding to that estimate.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

A summary of each interaction is plotted in Figure 1. Interpretation of interactions can be summarized as greater impacts of the within-person effect of social context on heavy episodic drinking when R-Ratios and breakpoints were high and demand elasticity was low (price insensitive demand).

Figure 1. Predicted Probabilities for Behavioral Economic Interaction Models.

Plotted are the predicted probabilities from generalized linear mixed effect models predicting heavy drinking days on days of alcohol use. Values are presented across the full range of the mean-centered behavioral economic variable. Location of the area including plus one or minus one standard deviation from the mean is provided by the vertically dashed lines. Predictions are plotted assuming the mean for the between-subject social context variable. Note that a linear transformation of demand elasticity values was conducted (x100) to facilitate model convergence.

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the association of social context with heavy drinking differs depending on if evaluated in the aggregate (i.e., between-person association) or specific to the contextual event (i.e., within-person association). This discordant finding is consistent with an ecological fallacy – specifically, Simpson’s paradox – in which the aggregate, “ecological” correlations do not match the individual, event-level correlations, resulting in inaccurate inferences about the individual based upon the group to which they belong (Kievit et al., 2013; Simpson, 1951). More specifically, heavy drinking was more likely in discrete drinking occasions for which other people were present compared to occasions for which an individual was alone (within-person effect). But, individuals reporting greater proportions of social drinking were less likely to report heavy drinking overall compared to individuals reporting lower proportions of social drinking (between-person effect). The results are consistent with other work examining between- and within-subject effects separately. They further clarify the differences between these findings by disaggregating these two mechanisms within a longitudinal framework.

Although the within-person association between social context and heavy drinking was robust when controlling for alcohol use severity (AUDIT), the between-person association was attenuated. These findings suggest that the between-person association was likely attributable to its covariation with alcohol use severity. More frequent drinking in the absence of social reward or contexts may reflect a general marker for alcohol use disorder symptoms. As such, we might expect greater alcohol use severity for individuals with more frequent solitary drinking episodes, supported by the finding that inclusion of AUDIT scores accounted for the between-person association. Importantly, the within-person relationships remained significant when controlling for AUDIT scores indicating that these patterns of behavior were also distinct from the severity of use, at least at a person level. The sex by social interaction is also consistent with research demonstrating a greater effect of the proximal social context for men compared to women (Murphy et al., 2006; Thrul and Kuntsche, 2015). Relevant to note is that we found greater likelihood of heavy drinking, rather than any alcohol use, in social situations for men compared to women. This is in line with work demonstrating that men report greater peer alcohol use in the immediate social network, including binge drinking (Acuff et al., 2020b), and that men who drink at similar levels to their peer group and who report more frequent heavy episodic drinking have higher social status (Dumas et al., 2014).

The study also extended research supporting behavioral economic indices as molar, prospective predictors of heavy drinking. We examined the interaction between the proximal social context and overall behavioral allocation captured by behavioral economic measures. Research shows that some molecular, momentary processes can increase or decrease alcohol demand in a discrete choice context (Acuff et al., 2020a). So, although behavioral economic indices are useful molar accounts of behavior, there may be interactive relations with contextual determinants of drinking decisions. Previous analyses in this sample demonstrated a prospective utility of behavioral economic indices at a between-person level (i.e., when treated as trait level predictors of typical patterns of behavior; Strickland et al., 2019). This study further demonstrates that these molar predictions depend on the environmental context for any single drinking event. Relevant to note is that these interactions were significant when a global measure of alcohol use severity was not (i.e., moderation by AUDIT), emphasizing the unique predictive capabilities of behavioral economics measures above established clinical measures.

It could be hypothesized that changes in the proximal context, and thus the constraints (costs or benefits) of a choice option, should have a greater impact on people with greater demand elasticity. However, the outcomes reported (i.e., greater impact for demand inelastic individuals and those with higher breakpoints) fit within the framework of values-based decision making (Field et al., 2020), akin to Herrnstein’s concept of melioration (Herrnstein, 1982). From this perspective, various internal and external signals are received in any given discrete choice context that dictate the fluctuating value of the various choice options in a manner similar to a cost/benefit ratio. Value signals accumulate (i.e., evidence accumulation) until the value of one of the choice options reaches a response threshold, at which point the corresponding behavior is executed – whether a deliberate calculation, or more likely, an inherent accumulation of signals based on context and behavioral history. Participants reporting high levels of relative reinforcing value of alcohol (e.g., low demand elasticity or high breakpoints) may already typically be on the threshold of preference for alcohol and are thus susceptible to changes in the context that pair with and increase the reinforcing value of alcohol (i.e., social connection). Indeed, this work supports the assumption that examining both molar and molecular mechanisms can increase predictability of drinking behavior and provides support for an emerging theoretical model describing the etiology of substance use disorders that describes targeted mechanisms for behavioral and pharmacological intervention at the person- and contextual-level. Future research would benefit from further testing these theory predictions through conceptual replication of the relationships here as well as evaluation of alternative contextual factors (e.g., proximal responsibilities or experienced consequences; Merrill and Aston, 2020; Skidmore & Murphy, 2011).

The current study used robust analyses of longitudinal data to examine the interaction between molar and proximal social determinants of heavy episodic drinking over a relatively long period of time. Limitations point to relevant next steps. First, we did not examine social behavior on days when alcohol was not consumed, and therefore we cannot predict whether social interaction leads to a greater likelihood of any drinking relative to solitary conditions. Based on preclinical work on environmental enrichment (Stairs and Bardo, 2009) and the potent reinforcement from social reward in discrete-choice experiments (Venniro et al., 2018), greater access to and engagement in substance-free social reward may be a protective factor against alcohol consumption, although this should be systematically examined. Second, molar behavioral economic measures were collected at one timepoint and therefore we do not know whether they fluctuated as a function of the social context. Recent work, has found that brief measures of alcohol demand are sensitive to contextual variables like prior day negative consequences (Merrill and Aston, 2020). Third, our analyses focused on heavy drinking and, therefore, generalizations to other substances should be tempered. It is possible that the role of social context may differ based on drug class given evidence that context modulates drug preference in both rodents and humans (i.e., a preference for cocaine outside the home, but heroin at home in Caprioli et al., 2009). Fourth, we did not measure alcohol use of others within the social context. However, should others in the social context be also consuming alcohol (a likely assumption, on average), our findings may be consistent with studies demonstrating a specific impact for the drug use behavior of a social partner in preclinical models of social contact (Smith, 2012). Fifth, the study recruited through a crowdsourcing site, which may introduce self-selection bias for individuals willing and able to complete remotely conducted research on an Internet platform.

The current study advances prior literature on social context by disaggregating and isolating the person-level versus event-level impacts of the social environment on heavy drinking. We find that individuals who drink more in a social context have a lower propensity to engage in heavy episodic drinking, however, a given person is more likely to experience heavy episodic drinking when in a social context. This outcome underscores social interaction as a critical proximal variable to consider for intervention development, such as in the increasingly popular just-in-time interventions emphasizing contextual determinants. Yet, these findings also stress the importance of context. Frequent drinking in social contexts was not a de facto marker for problematic alcohol use; in fact, solitary drinking was a between-person predictor of more severe use patterns. Molar behavioral economic indices of substance-related behavior were also predictive of the impact of social context in support of hypotheses of values-based decision-making frameworks. Collectively, these results demonstrate an ecological fallacy (i.e., Simpson’s paradox) made clear through disaggregation of within- and between-subject effects as well as highlight the potential for merging behavioral economic theory with contextual variables in the proximal environment to better predict heavy drinking.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We evaluate between- and within-person effects of sociality on heavy drinking

Between-person effects showed reduced heavy drinking with greater sociality

Within-person effects showed greater heavy drinking in social contexts

Within-person effects were stronger for people with higher alcohol demand

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32 DA07209), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31 AA027140), Pilot Funds from the University of Kentucky Center on Drug and Alcohol Research, and Professional Development Funds from the University of Kentucky. These funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, or preparation and submission of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, or University of Kentucky.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The winsorization process means that values that were 1.5 times the IQR added to the 3rd quartile and 1.5 times the IQR subtracted from the 1st quartile would be winsorized. Number of outliers in each variable: intensity = 4: breakpoint = 0: Omax = 6; Pmax = 0; elasticity = 19; R-Ratio = 9; delay discounting = 5.

This interaction can also be interpreted such that the difference between heavy drinking for men and women is larger in a non-social than social context.

References

- Acuff SF, Amlung M, Dennhardt AA, MacKillop J, Murphy JG, 2020a. Experimental manipulations of behavioral economic demand for addictive commodities: a meta-analysis. Addiction 115(5), 817–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuff SF, Dennhardt AA, Correia CJ, Murphy JG, 2019. Measurement of substance-free reinforcement in addiction: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev 70, 79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuff SF, MacKillop J, Murphy JG, 2020b. Integrating behavioral economic and social network influences in understanding alcohol misuse in a diverse sample of emerging adults. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 44, 1444–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuff SF, Murphy JG, 2017. Further examination of the temporal stability of alcohol demand. Behav. Processes 141(1), 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuff SF, Soltis KE, Murphy JG, 2020c. Using demand curves to quantify the reinforcing value of social and solitary drinking. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 44, 1497–1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung M, MacKillop J, 2015. Further evidence of close correspondence for alcohol demand decision making for hypothetical and incentivized rewards. Behav. Processes 113, 187–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Neisewander JL, Kelly TH, 2013. Individual differences and social influences on the neurobehavioral pharmacology of abused drugs. Pharmacol. Rev 65(1), 255–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S, 2014. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. arXiv 1406.5823. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, Murphy JG, 2014. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol 10, 641–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilevicius E, Single A, Rapinda KK, Bristow LA, Keough MT, 2018. Frequent solitary drinking mediates the associations between negative affect and harmful drinking in emerging adults. Addict. Behav 87, 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli D, Celentano M, Dubla A, Lucantonio F, Nencini P, Badiani A, 2009. Ambience and drug choice: cocaine- and heroin-taking as a function of environmental context in humans and rats. Biol. Psychiatry 65(10), 893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2020. Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DJ, Dallery J, 2016. Effects of delay and probability combinations on discounting in humans. Behav. Processes 131, 15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas TM, Graham K, Bernards S, & Wells S, 2014. Drinking to reach the top: Young adults’ drinking patterns as a predictor of status within natural drinking groups. Addict. Behav 39(10), 1510–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Heather N, Murphy JG, Stafford T, Tucker JA, Witkiewitz K, 2020. Recovery from addiction: Behavioral economics and value-based decision making. Psychol. Addict. Behav 34(1), 182–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Collins RL, Bradizza CM, 2009. Solitary and social heavy drinking, suicidal ideation, and drinking motives in underage college drinkers. Addict. Behav 34(12), 993–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, Epstein DH, Nader MA, Shaham Y, 2016. Time to connect: bringing social context into addiction neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 17(9), 592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ (1982). Melioration as behavioural dynamism In Commons ML: Herrnstein RJ & Rachlin H (Eds.), Quantitative analyses of behavior, vol. II: Matching and maximizing accounts, pp. 433–58. Ballinger Publishing Co., Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Hofford RS, Bond PN, Chow JJ, Bardo MT, 2020. Presence of a social peer enhances acquisition of remifentanil self-administration in male rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 213, 108125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Roma PG, 2013. Behavioral economics and empirical public policy. J. Exp. Anal. Behav 99(1), 98–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennison KM, 2004. The short-term effects and unintended long-term consequences of binge drinking in college: a 10-year follow-up study. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 30(3), 659–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough MT, O’Connor RM, Stewart SH, 2018. Solitary drinking is associated with specific alcohol problems in emerging adults. Addict. Behav 76, 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kievit RA, Frankenhuis WE, Waldorp LJ, Borsboom D, 2013. Simpson’s paradox in psychological science: a practical guide. Front. Psychol 4, 513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Bickel WK, 2014. A 5-trial adjusting delay discounting task: accurate discount rates in less than one minute. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 22(3), 222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Franck CT, Stein JS, Bickel WK, 2015. A modified exponential behavioral economic demand model to better describe consumption data. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 23(6), 504–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafo MR, 2011. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacol. 216(3), 305–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellis AM, Bickel WK, 2020. Mechanical Turk data collection in addiction research: utility, concerns and best practices. Addiction, 115, 1960–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Aston ER, 2020. Alcohol demand assessed daily: Validity, variability, and the influence of drinking-related consequences. Drug Alcohol Depend. 208, 107838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris V, Amlung M, Kaplan BA, Reed DD, Petker T, MacKillop J, 2017. Using crowdsourcing to examine behavioral economic measures of alcohol value and proportionate alcohol reinforcement. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 25(4), 314–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Barnett NP, Colby SM, 2006. Alcohol-related and alcohol-free activity participation and enjoyment among college students: a behavioral theories of choice analysis. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 14(3), 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Correia CJ, Colby SM, Vuchinich RE, 2005. Using behavioral theories of choice to predict drinking outcomes following a brief intervention. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 13(2), 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, 2006. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 14(2), 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse Alcoholism, 2007. Helping Patients who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide: Updated 2005 Edition. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD, 2015. 2010 National and State Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Am. J. Prev. Med 49(5), e73–e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Creswell KG, Dimoff JD, Fairbairn CE, Cohn JF, Heckman BW, Kirchner TR, Levine JM, Moreland RL, 2012. Alcohol and group formation: a multimodal investigation of the effects of alcohol on emotion and social bonding. Psychol. Sci 23(8), 869–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson EH, 1951. The interpretation of interaction in contingency tables. J. Royal Stat. Soc.: Series B 13(2), 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore JR, & Murphy JG, 2011. The effect of drink price and next-day responsibilities on college student drinking: A behavioral economic analysis. Psychol. Addict. Behav 25(1). 57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, 2012. Peer influences on drug self-administration: social facilitation and social inhibition of cocaine intake in male rats. Psychopharmacol. 224(1), 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Lacy RT, Strickland JC, 2014. The effects of social learning on the acquisition of cocaine self-administration. Drug Alcohol Depend. 141, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stairs DJ, Bardo MT, 2009. Neurobehavioral effects of environmental enrichment and drug abuse vulnerability. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 92(3), 377–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JS, Koffarnus MN, Snider SE, Quisenberry AJ, Bickel WK, 2015. Identification and management of nonsystematic purchase task data: Toward best practice. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 23(5), 377–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JC, Alcorn JL 3rd, Stoops WW, 2019. Using behavioral economic variables to predict future alcohol use in a crowdsourced sample. J. Psychopharmacol 33(7), 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JC, Smith MA, 2014. The effects of social contact on drug use: Behavioral mechanisms controlling drug intake. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 22(1), 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JC, Stoops WW, 2017. Stimulus selectivity of drug purchase tasks: A preliminary study evaluating alcohol and cigarette demand. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 25(3), 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JC, Stoops WW, 2018. Feasibility, acceptability, and validity of crowdsourcing for collecting longitudinal alcohol use data. J. Exp. Anal. Behav 110(1), 136–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JC, Stoops WW, 2019. The Use of Crowdsourcing in Addiction Science Research: Amazon Mechanical Turk. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 27(1), 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND, 2018. Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999–2016: observational study. BMJ 362, k2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrul J, Kuntsche E, 2015. The impact of friends on young adults’ drinking over the course of the evening--an event-level analysis. Addiction 110(4), 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venniro M, Shaham Y, 2020. An operant social self-administration and choice model in rats. Nat. Protoc 15(4), 1542–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venniro M, Zhang M, Caprioli D, Hoots JK, Golden SA, Heins C, Morales M, Epstein DH, Shaham Y, 2018. Volitional social interaction prevents drug addiction in rat models. Nat. Neurosci 21(11), 1520–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, 1995. Alcohol abuse as molar choice: An update of a 1982 proposal. Psychol. Addict. Behav 9(4), 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Heather N, 2003. Choice, behavioral economics, and addiction. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Wang LP, Maxwell SE, 2015. On disaggregating between-person and within-person effects with longitudinal data using multilevel models. Psychol. Methods 20(1), 63–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvorsky I, Nighbor TD, Kurti AN, DeSarno M, Naudé G, Reed DD, Higgins ST, 2019. Sensitivity of hypothetical purchase task indices when studying substance use: A systematic literature review. Prev. Med 128, 105789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.