Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The 30-day direct oral anticoagulant starter pack has simplified the treatment of acute venous thromboembolisms, but it is not appropriate for use in patients with other indications for anticoagulation.

METHODS:

A retrospective analysis of national outpatient pharmacy claims data between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2018, was performed. Adult patients (ages >18 years) with continuous insurance enrollment at least 12 months prior to and 1 month following a direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription during the study period were included. The primary study outcome was the rate of inappropriate prescription of direct oral anticoagulant starter packs, defined as a prescription without a venous thromboembolism diagnosis within the prior 45 days or a prescription with a prior starter pack fill within the past 45 days.

RESULTS:

A total of 3711 direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription fills were identified, representing 3634 unique patients. The mean patient age was 62.8 years (standard deviation [SD] 15.1) and 1871 (50.4%) were females. There were 770 (20.7%) direct oral anticoagulant starter pack fills identified as potentially inappropriate. Patients prescribed inappropriate fills were likely to be older than patients with appropriate fills (64.7 years vs 62.4 years, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the race or geographic location between patients with inappropriate and appropriate prescriptions.

CONCLUSIONS:

A significant proportion of patients using direct oral anticoagulant starter packs did not have a diagnosis of acute venous thromboembolism, raising concerns about inappropriate prescribing and potential bleeding complications. Future studies are needed to identify factors associated with inappropriate direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription and evaluate efforts to reduce this practice.

Keywords: Anticoagulation, Atrial fibrillation, Prescription, Starter pack, Thrombosis

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of venous thromboembolism, consistent of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, has been transformed since the introduction of direct oral anticoagulant medications. Specifically, 2 direct oral anticoagulants (apixaban and rivaroxaban) offer an oral-only treatment option that avoids the need for parenteral heparin lead-in.1 This strategy uses a higher total daily dose for the first 7-21 days before returning to standard doses for the remainder of the initial 3-month treatment period.2-5

Direct oral anticoagulant dosing for venous thromboembolism is uniquely different than for atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter and other indications.6,7 To simplify this complex dosing regimen, 30-day apixaban and rivaroxaban starter packs were made available for acute venous thromboembolism treatment. However, these starter packs should not be used for other indications (eg, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter) or as a refill because of their unique dosing regimen. We aim to describe the frequency of off-label direct oral anticoagulant starter packs using a large national insurance claims database.

METHODS

We performed a 4-year (2015-2018) retrospective analysis of claims data in Optum’s De-identified Clinfor-matics Data Mart, a national commercial and Medicare Advantage claims database. This study was determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan.

We identified patients ages >18 years who had apixaban or rivaroxaban starter pack outpatient pharmacy claims between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2018. We excluded patients who had pregnancy-related claims within 12 months prior to or 1 month after direct oral anticoagulant starter pack claims. We only included patients with continuous insurance coverage from 12 months prior to until 1 month after the pharmacy claims. The unit of analysis was index direct oral anticoagulant starter pack fills, and thus, individual patients may have more than 1 index fill in the analysis.

Both medical indication and fill status (new prescription vs renewal) were applied to determine the appropriateness of direct oral anticoagulant starter pack fills. We identified the medical indications acute venous thromboembolism and atrial fibrillation based on diagnosis codes (eTable 1, available online) from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). An acute venous thromboembolism was considered to be associated with a direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription if there was an acute venous thromboembolism diagnosis within 45 days prior to the medication fill. An atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter diagnosis was considered to be associated with a direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription if the atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter diagnosis was within 6 months prior to the prescription fill. We assumed a 30-day supply for each direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription. An index direct oral anticoagulant starter pack fill was assumed to be a new prescription if there was no prior direct oral anticoagulant starter pack fill in a clean period of 45 days, or if the gap in days was greater than 45 days from the end of the 30-day supply of the previous fill to the start of the index fill.

Outcome Measures and Covariates

The main outcome of interest was the rate of inappropriate prescription of direct oral anticoagulant starter packs. A direct oral anticoagulant start pack prescription was considered inappropriate if there was no venous thromboembolism diagnosis within 45 days prior to fill date or if there was a previous starter pack fill within the 45 days prior to fill date of the index direct oral anticoagulant starter pack, indicating the index fill as a refill. Patient demographics (ie, age, gender, race/ethnicity, US census region) were identified from membership files.

Sensitivity Analysis

To associate an acute venous thromboembolism diagnosis with a direct oral anticoagulant starter pack fill, we tested additional time windows to identify a venous thromboembolism diagnosis within 30 and 60 days prior to a direct oral anticoagulant starter pack fill. To mitigate the possibility of missed or delayed billing, a venous thromboembolism diagnosis up to 15 days after a direct oral anticoagulant starter pack fill was also explored.

Statistical Analysis

We reported the rate of inappropriate direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription after applying 2 criteria, medical indication and prescription status. Descriptive and comparative statistics were calculated for demographic variables. Comparison by appropriate status was performed using χ2 tests and Fisher exact tests for binary variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables. A 2-tailed P < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

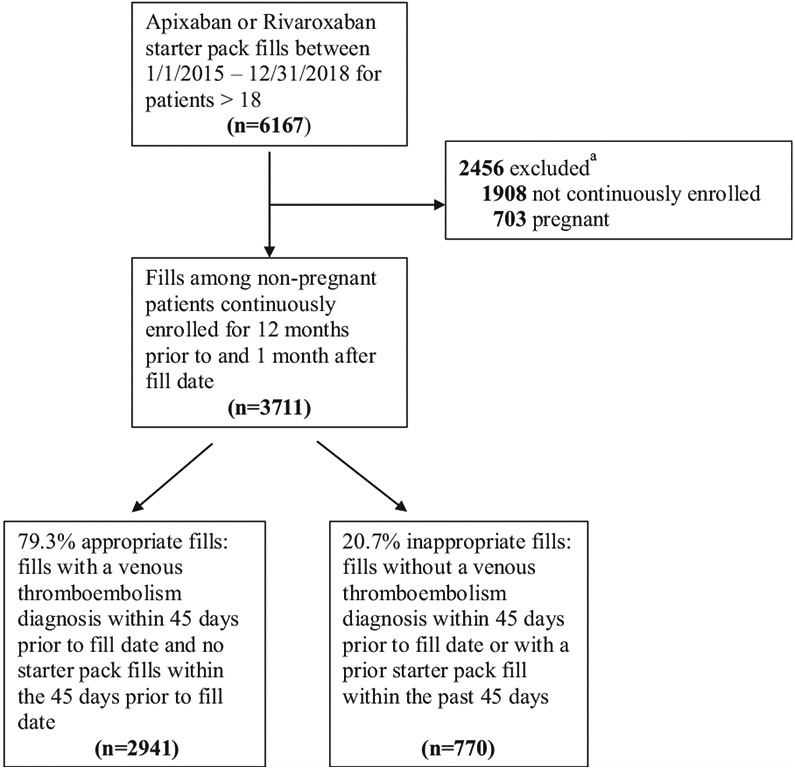

We identified 3711 direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescriptions representing 3634 unique patients who met study criteria (Figure). The mean patient age was 62.8 years (standard deviation [SD] 15.1) and 1871 (50.4%) were females (Table 1). Of the 3711 starter pack prescriptions, 3220 (86.8%) were for a rivaroxaban starter pack and 770 (20.7%) were potentially inappropriate.

Figure.

Flow diagram of study cohort selection.

aSome fills are excluded for both criteria.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Study Cohort by Appropriateness of Starter Pack Fill*

| Total (n = 3711) | Appropriate (n = 2941) | Inappropriate (n = 770) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rivaroxaban | 3220 (86.8) | 2566 (87.2) | 654 (84.9) | 0.09 |

| Age at fill date, mean (SD) | 62.8 (15.1) | 62.4 (15.3) | 64.7 (14.1) | < 0.001 |

| % Female | 1871 (50.4) | 1469 (49.9) | 402 (52.2) | 0.27 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.10 | |||

| Asian | 51 (1.4) | 39 (1.3) | 12 (1.6) | |

| Black | 519 (14.0) | 426 (14.5) | 93 (12.1) | |

| Hispanic | 248 (6.7) | 184 (6.3) | 64 (8.3) | |

| White | 2471 (66.6) | 1966 (66.8) | 505 (65.6) | |

| Unknown | 422 (11.4) | 326 (11.1) | 96 (12.5) | |

| Census Region | 0.67 | |||

| Midwest | 997 (26.9) | 803 (27.3) | 194 (25.2) | |

| Northeast | 297 (8.0) | 234 (8.0) | 63 (8.2) | |

| South | 1576 (42.5) | 1250 (42.5) | 326 (42.3) | |

| West | 834 (22.5) | 649 (22.1) | 185 (24.0) | |

| Unknown | 7 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) |

Data presented is the number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated. Comparison between the 2 groups was performed using χ2 tests and Fisher exact tests for binary variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables. SD = standard deviation.

Patients with a potentially inappropriate prescription were likely to be older (64.7 years vs 62.4 years, P < 0.001). There was no difference in the race or geographic region between patients who were appropriately prescribed and inappropriately prescribed a starter pack. Among the 770 potentially inappropriate prescription fills, 52 (6.8%) were starter pack renewals, 217 (28.2%) were associated with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter but without a diagnosis of acute venous thromboembolism, and 520 (67.5%) were not associated with either a venous thromboembolism or atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter diagnosis.

In the sensitivity analysis, rates of potentially inappropriate direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription ranged from 17.5% to 21.2% across varying lengths of time between a direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription and venous thromboembolism diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rates of Inappropriate Starter Pack Prescription Based on Time of Venous Thromboembolism Diagnosis in Relation to Starter Pack Fill Date (Sensitivity Analysis)

| Days Between Venous Thromboembolism Diagnosis and Starter Pack Fill |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 1 day | 2 days | 3 days | 4 days | 5 days | 6 days | 7 days | 15 days | ||

| Days of Venous Thromboembolism | in 30 days | 21.2% | 20.8% | 20.6% | 20.3% | 20.0% | 19.8% | 19.8% | 19.6% | 18.3% |

| Diagnosis Before Starter Pack Fill | in 45 days | 20.7% | 20.3% | 20.1% | 19.8% | 19.6% | 19.3% | 19.3% | 19.1% | 17.9% |

| in 60 days | 20.3% | 19.9% | 19.8% | 19.5% | 19.2% | 19.0% | 18.9% | 18.8% | 17.5% | |

DISCUSSION

In this national study, up to 1 in 5 direct oral anticoagulant starter packs may be prescribed inappropriately. These most often occurred without an acute venous thromboembolism event or as a refill prescription. Due to the use of higher total daily dosing in the first 7-21 days, inappropriate use of direct oral anticoagulant starter packs places patients at increased risk for bleeding complications.

Older patients in this study were more likely to receive an inappropriate starter pack prescription. This is consistent with previous studies that show patients at older age are more likely to receive inappropriate prescriptions due to polypharmacy and the presence of multiple comorbidities.8-10 In those studies, patients with inappropriate prescriptions are also more likely to require emergency department visits, experience adverse drug events, and be hospitalized.11 We found no difference in the race or geographic location between patients who were inappropriately prescribed a starter pack and those who were appropriately prescribed.

It is possible that patients without acute venous thromboembolisms were prescribed direct oral anticoagulant starter packs for other acute thrombotic events, including left ventricular thrombus and peripheral arterial thrombus. However, direct oral anticoagulants are not currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for these indications, and some data suggests that they may be less effective than warfarin.12 Data on appropriate dosing for these indications and the need for a higher dose in the first 1-3 weeks is lacking for these potential indications.

Our study has a number of limitations that should be considered. First, pharmacy claims are not directly linked to the indication for prescription; thus, our results are largely contingent on the presence of an associated acute venous thromboembolism diagnosis to determine prescription appropriateness. Second, among inappropriate fills, we only reported atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter as a potential medical indication. A majority of inappropriate fills were for indications other than venous thromboembolism or atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, for which these 2 medications are not approved for by the Food and Drug Administration. Lastly, our data consisted of limited information on prescriber details, and thus, we were unable to conduct an analysis on prescriber characteristics associated with inappropriate prescriptions.

CONCLUSIONS

Approximately 1 in 5 direct oral anticoagulant starter packs may be prescribed inappropriately. Use of higher than necessary anticoagulant doses may lead to bleeding-related adverse drug events and increased health care resource utilization. Future studies are needed to identify factors associated with inappropriate direct oral anticoagulant starter pack prescription and evaluate efforts to reduce this practice.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE.

Between 2015 and 2018, 20.7% of starter pack fills were identified as potentially inappropriate.

Patients who received an inappropriate fill were likely to be older but without racial or geographic differences.

High rates of direct oral anticoagulant starter pack use without an acute venous thromboembolism diagnosis place patients at increased risk for bleeding complications.

Clinicians should take caution and avoid prescribing starter packs to patients without an acute venous thromboembolism diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K01 HL135392), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R18 HS026874), and the Short-Term Biomedical Research Training Program. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: GDB discloses consulting fees from Pfizer/Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Portola, AMAG Pharmaceuticals, and Acelis Connected Health. YF received funding from the Short-Term Biomedical Research Training Program. KS reports none

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.06.045.

References

- 1.Serhal M, Barnes GD. Venous thromboembolism: a clinician update. Vase Med 2019;24(2):122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013;369(9):799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EINSTEIN Investigators, Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2010;363(26):2499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EINSTEIN–PE Investigators, Büller HR, Prins MH, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2012;366(14):1287–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 2014;35(43):3033–69 [3069a-3069k]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365 (11):981–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365(10):883–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanlon JT, Artz MB, Pieper CF, et al. Inappropriate medication use among frail elderly inpatients. Ann Pharmacother 2004;38(1):9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki Y, Sakakibara M, Shiraishi N, Hirose T, Akishita M, Kuzuya M. Prescription of potentially inappropriate medications to older adults. A nationwide survey at dispensing pharmacies in Japan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2018;77:8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franchi C, Antoniazzi S, Proietti M, Nobili A, Mannucci PM, SIM-AF Collaborators. Appropriateness of oral anticoagulant therapy prescription and its associated factors in hospitalized older people with atrial fibrillation. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84(9):2010–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liew TM, Lee CS, Goh Shawn KL, Chang ZY. Potentially inappropriate prescribing among older persons: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Fam Med 2019;17(3):257–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson AA, Trankle CR, Eubanks G, et al. Off-label use of direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin for left ventricular thrombi. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5(6):685–92. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0652.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.