Abstract

Objective:

This study evaluated the contributions of clinical, sociodemographic, and service use variables to the risk of early readmission, defined as readmission within 30 days of discharge following hospitalization for any medical reason (mental or physical illnesses), among patients with mental disorders in Quebec (Canada).

Methods:

In this longitudinal study, 2,954 hospitalized patients who had visited 1 of 6 Quebec emergency departments (ED) in 2014 to 2015 (index year) were identified through clinical administrative databanks. The first hospitalization was considered that may have occurred at any Quebec hospital. Data collected between 2012 and 2013 and 2013 and 2014 on clinical, sociodemographic, and service use variables were assessed as related to readmission/no readmission within 30 days of discharge using hierarchical binary logistic regression.

Results:

Patients with co-occurring substance-related disorders/chronic physical illnesses, serious mental disorders, or adjustment disorders (clinical variables); 4+ outpatient psychiatric consultations with the same psychiatrist; and patients hospitalized for any medical reason within 12 months prior to index hospitalization (service use variables) were more likely to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Patients who made 1 to 3 ED visits within 1 year prior to the index hospitalization, had their index hospitalization stay of 16 to 29 days, or consulted a physician for any medical reason within 30 days after discharge or prior to the readmission (service use variables) were less likely to be rehospitalized.

Conclusions:

Early hospital readmission was more strongly associated with clinical variables, followed by service use variables, both playing a key role in preventing early readmission. Results suggest the importance of developing specific interventions for patients at high risk of readmission such as better discharge planning, integrated and collaborative care, and case management. Overall, better access to services and continuity of care before and after hospital discharge should be provided to prevent early hospital readmission.

Keywords: early readmission, hospitalization, associated variables, emergency department, ambulatory mental health care, serious mental health disorders, common mental disorders, Quebec

Abstract

Objectif:

La présente étude a évalué les contributions des variables cliniques, sociodémographiques et d’utilisation des services au risque de réhospitalisation précoce, définie comme étant une réhospitalisation dans les 30 jours suivant le congé après une hospitalisation pour une raison médicale (maladies mentales ou physiques), chez des patients souffrant de troubles mentaux au Québec (Canada).

Méthodes:

Dans cette étude longitudinale, 2 954 patients hospitalisés qui avaient fait une visite à l’un de six services d’urgence (SU) du Québec en 2014-2015 (année par index) ont été identifiés à l’aide des bases de données clinico-administratives. La première hospitalisation était estimée avoir eu lieu dans n’importe quel hôpital du Québec. Les données recueillies entre 2012-2013 et 2013-2014 sur les variables cliniques, sociodémographiques et d’utilisation des services ont été évaluées en lien avec une réhospitalisation/aucune réhospitalisation dans les 30 jours suivant le congé, à l’aide de la régression logistique binaire hiérarchique.

Résultats:

Les patients souffrant de troubles concomitants de dépendance aux substances ou de maladies physiques chroniques, de troubles mentaux sérieux ou de troubles d’adaptation (variables cliniques); ayant 4 consultations psychiatriques ambulatoires ou plus avec le même psychiatre; et les patients hospitalisés pour une raison médicale dans les 12 mois précédant l’hospitalisation d’indice (variables d’utilisation des services) étaient plus susceptibles d’être réhospitalisés dans les 30 jours suivant le congé. Les patients qui ont fait 1-3 visites au SU dans l’année précédant l’hospitalisation d’indice avaient une durée d’hospitalisation d’indice de 16 à 29 jours, ou qui consultaient un médecin pour une raison médicale dans les 30 jours suivant le congé ou avant une réhospitalisation (variables d’utilisation des services) étaient moins susceptibles d’être réhospitalisés.

Conclusions:

La réhospitalisation précoce était plus fortement associée aux variables cliniques, suivies des variables d’utilisation des services, les deux jouant un rôle essentiel pour prévenir la réhospitalisation précoce. Les résultats suggèrent l’importance d’élaborer des interventions spécifiques pour les patients à risque élevé d’une réhospitalisation comme une meilleure planification du congé, des soins intégrés en collaboration, et la gestion de cas. En général, un meilleur accès aux services et la continuité des soins avant et après le congé de l’hôpital devraient être fournis pour prévenir la réhospitalisation précoce.

Introduction

Early hospital readmission, defined as readmission within 30 days of previous discharge, is considered the most accurate measure of the quality of care provided during the previous hospitalization, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development mental health (MH) Panel1–3 and also the best indicator of effectiveness for postdischarge services offered in the community.4 Readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge represents a negative clinical outcome4,5 revealing discontinuity in care. Early readmission is associated with high health care costs6,7 and increased wait times for access to inpatient units.8

Patients with mental disorders (MD) have the highest readmission rates of all hospitalized patients.9,10 The risk for readmission is particularly high in the immediate postdischarge period.11–14 Previous studies found that 5% to 15% of patients hospitalized for MD had an early readmission.6,15–17 Other studies have identified associations between MD and risk of early readmission due to physical illnesses18–22 such as heart failure,19,20,22 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,19,21 pneumonia,22 or diabetes.19

Studies suggest that previous hospitalization was the only variable consistently associated with early readmission among patients with MD.11,23–27 Mixed results emerged between length of hospitalization and early readmission, most studies finding associations between longer stay and reduced readmission,6,24,28,29 while others30,31 found the opposite, likely due to different benchmarks for length of stay. Other service use variables associated with early readmission were lack of discharge planning,11 health insurance,26 and follow-up soon after discharge.8,32 Concerning clinical variables, higher risk of early readmission was identified in association with schizophrenia,5,33 bipolar disorders,5,33,34 alcohol use disorder,6 drug use disorders,34 co-occurring physical and/substance-related disorders (SRD),35 co-occurring MD/SRD,30,35 symptom acuity,11,36 and lower functionality,26 while other studies found no associations between early readmission and clinical variables.32,37 Sociodemographic variables associated with early readmission in the literature included homelessness or unstable housing,16,26 unemployment and poverty25 lack of social support,7,16 living alone, civil status, and legal problems.7 Regarding age, studies on patients with MD found positive associations between age and early admission in the 25 to 34, 35 to 44,7 and younger age groups.11 Overall readmission rates were similar between men and women.6,29

To our knowledge, no prior studies have assessed factors associated with early hospital readmission for any medical reason, whether mental or physical conditions, among patients with MD. Moreover, most previous research on early admission among patients with MD assessed very few variables. Service use variables in particular have been understudied, such as type of region where the patient was hospitalized and continuity of care, including number of visits with the same general practitioner (GP) or the same psychiatrist, and number of psychosocial interventions provided in public primary care. Moreover, the relative weight of clinical, sociodemographic, and service use variables in early readmission have yet to be identified, which may help decision makers and clinicians charged with planning postdischarge services identify and implement more targeted interventions that may help reduce early readmission.

This study evaluated the respective contributions of sociodemographic, clinical, and service use variables to early hospital readmission for any medical reason among patients with MD in Quebec. Having included several service use variables not previously tested, we hypothesized that early readmission for any medical reason among these patients would be more strongly associated with variables involving service use, access or continuity of health care, than with clinical or sociodemographic variables.

Methods

Study Population and Design

In this longitudinal study, 2,954 patients diagnosed with MD and hospitalized for any medical reason (whether mental of physical conditions) in 2014 to 2015 (index year) were identified through clinical administrative databanks. Participants were 12 years or older and eligible for Quebec health insurance (Régie d’Assurance Maladie du Québec [RAMQ]) during the study period: 2012 to 2015. They had visited 1 of 6 selected emergency departments (ED) located in university and peripheral health regions at least once during the index year: April 1, 2014, to March 31, 2015. The first patient hospitalization in 2014 to 2015 was considered and may have taken place in any Quebec hospital. The Access to Information Commission of Quebec and the ethics committee of a MH university institute approved the study protocol.

Data Sources

Medical administrative data were collected from the RAMQ databanks, which include billing systems for most physician services, only 6% of which occur outside the public health insurance system.38 Demographic and socioeconomic information, including material and social deprivation indices, were also available,39 as were data from the hospitalization/discharge databank (Maintenance et exploitation de données pour l’étude de la clientèle hospitalière [MED-ECHO]). The Quebec emergency databank (Banque de données commune des urgences [BDCU]) provided additional information on, for example, patients with family physicians, illness acuity, and reasons for ED use. The local community health service center databank (Système d’information clinique et administrative des centres locaux de services communautaires), also used for this study, contained data on biopsychosocial and MH services offered in public primary care, including medical interventions provided by salaried GP.

Variables

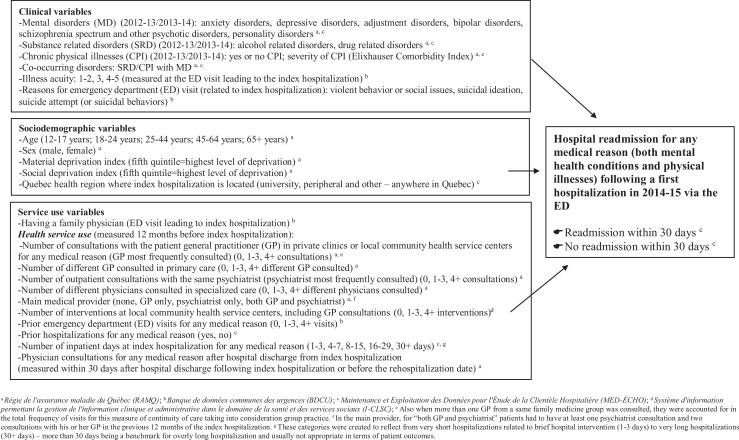

The dichotomous dependent variable was hospital readmission (yes/no) within 30 days of discharge following the index (first) hospitalization for any medical reason in 2014 to 2015. Independent variables, including clinical, sociodemographic, and service use variables, are shown in Figure 1 and linked to their specific databanks. Clinical variables included MD including SRD, chronic physical illnesses, co-occurring disorders, reasons for the ED visit leading to index hospitalization: suicidal ideation or attempt (suicide behaviors), violent behavior or social issues, and illness acuity. MD as designated in the RAMQ databank were based on the International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision (ICD-9), and those in the MED-ECHO and BDCU databanks, from the Tenth Revision (ICD-10-CA). MD included anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, adjustment disorders (common MD); bipolar disorders, schizophrenia spectrum, and other psychotic disorders (serious MD); and personality disorders. SRD comprised alcohol-related disorders (alcohol use disorders, alcohol induced disorders, alcohol intoxication) and drug-related disorders (drug use disorders, drug induced disorders, drug intoxication). Diagnostic codes for MD and SRD are shown in Table 1. Based on the Elixhauser comorbidity index,40 having chronic physical illnesses or not and level of severity (0 to 3+) were recorded. Different combinations of co-occurring disorders involving SRD and chronic physical illnesses were included. SRD and MD had to be recorded at least once prior to the index year (in 2012 to 2013 or 2013 to 2014); and chronic physical illnesses either twice yearly in the RAMQ databank or once in the MED-ECHO as established in previous research.41 Suicidal, social, or violent behavioral issues and reasons for ED visit leading to index hospitalization were extracted from the 2014 to 2015 BDCU. The Canadian Triage Acuity Scale42 was used to measure illness acuity at the ED visit prior to index hospitalization, ranging from levels 1 to 2 (immediate and very urgent), 3 (urgent), to 4 to 5 (less urgent and non-urgent care). Levels 4 and 5 indicate the appropriateness of outpatient treatment over ED.42

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: variables tested for association with rehospitalization/no rehospitalization within 30 days of discharge following a first hospitalization in 2014 to 2015 for any medical reason among patients with mental disorders.

Table 1.

Codes for Mental Disorders (MD) and Substance-related Disorders (SRD) according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions.

| Diagnoses | International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) | International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol use disorders | 303.0, 303.9, 305.0 | F10.1-F10.2 |

| Drug use disorders | 304, 305.2-305.7, 305.9 | F11.1, F11.2, F12.1, F12.2, F13.1, F13.2, F14.1, F14.2, F15.1, F15.2, F16.1, F16.2, F18.1, F18.2, F19.1, F19.2, F55 |

| Alcohol-induced disorders | 291.0-291.5, 291.8, 291.9 | F10.3-F10-9 |

| Drug-induced disorders | 292.0-292.2, 292.8, 292.9 | F11.3-F11.9, F12.3-F12.9, F13.3-F13.9, F14.3-F14.9, F15.3-F15.9, F16.3-F16.9, F18.3-F18.9, F19.3-F19.9 |

| Alcohol intoxication | 980.0, 980.1, 980.8, 980.9 | F10.0, T51.0, T51.1, T51.8, T51.9 |

| Drug intoxication | 965.0, 965.8, 967.0, 967.6, 967.8, 967.9, 969.4-969.9, 970.8, 982.0, 982.8 | F11.0, F12.0 F13.0, F14.0, F15.0, F16.0, F18.0, F19.0, T40, T42.3, T42.4, T42.6, T42.7, T43.5, T43.7-T43.9, T50.9, T52.8, T52.9 |

| Depressive disorders | 300.4, 311 | F32-F34 |

| Anxiety disorders | 300, except 300.4 | F40-F48, F68 |

| Adjustment disorders | 308, 309, 313 | F93.0, F94.0 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders | 295, 297, 298 | F20, F21, F22, F23, F24, F25, F28, F29, F32.3, F33.3, F44.89 |

| Bipolar disorders | 296 | F30, F31, F38, F39 |

| Personality disorders | 301 | F60, F070, F340, F341, F488, F61, F62, F681, F688, F69 |

| Other MD (e.g., other organic psychotic conditions, eating disorders) | 293, 294,302 (except 302.6) 307, 310, 312, 315 | F04-F09, F17, F38, F39, F50-F59, F61-F69 (except F64.2), F80-89, F90-99 |

Sociodemographic variables included sex (male, female), age (categorized as 12 to 17, 18 to 24, 25 to 44, 45 to 64, and 65+ years), health regions, and material and social deprivation derived from the Canadian census (2011).39 Quebec health regions were measured for the index hospitalization and classified as university, peripheral, and other regions (intermediary and remote regions). The material deprivation index considers individual to population employment ratios, proportion of individuals without a high school diploma, and average income.39 The social deprivation index includes data on individuals living alone, single-parent families, and civil status.39 Both indices are classified in quintiles, with the fifth quintile representing highest level of deprivation.

Service use variables included having a family physician and health service use in the 12 months preceding the index hospitalization, that is, number of consultations with the patient GP (i.e., the GP mostly frequently consulted) for any medical reason in primary care (0, 1 to 3, 4+);43 number of consultations with the patient outpatient psychiatrist (the one mostly seen; 0, 1 to 3, 4+); number of different GP consulted in primary care (0, 1 to 3, 4+); number of different physicians consulted in specialized care (0, 1 to 3, 4+); main medical provider (none, GP only, psychiatrist only, both GP and psychiatrist);44 number of interventions at local community health service centers including GP consultations (0, 1 to 3, 4+); prior consultations at ED (0, 1 to 3, 4+); prior hospitalizations for any medical reason (yes/no); and number of inpatient days at the index hospitalization for any medical reason (1 to 3, 4 to 7, 8 to 15, 16 to 29, 30+). Finally, physician consultations for any medical reason after discharge from the index hospitalization were measured within 30 days of discharge or before readmission if prior to 30 days.

Statistical Analyses

Only 0.5% of the data were missing, so the complete cases were used for the multivariable regression. Descriptive analyses were performed including 2-way frequency tables for independent variables, in association with the dependent variable (yes/no for readmission within 30 days of discharge). As the effect of clustering at the hospital-center level (62 hospital units) was small (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.096), a multilevel model was not needed. Collinearity statistics were tested using variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerance tests, with 5 as the maximum level of VIF. Independent variables without collinearity were entered in the model at alpha value P < 0.10. Hierarchical logistic regression was conducted, with clinical variables introduced first into the model, as the variables most highly correlated with ED visits and hospitalizations according to the literature, followed by sociodemographic variables, then service use variables.45–47 A stepwise forward method was also used for the estimation of parameters in the hierarchical logistic regression model. Odds ratios were calculated with 95% confidence intervals. The reference category was patients not hospitalized within 30 days of hospital discharge. All analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0.

Results

After removal of the 100 patients (3.3%) not hospitalized via ED, the remaining cohort included 2,954 patients with MD hospitalized for any medical reason via the ED, 51% for MH conditions and 49% for physical illnesses. Of these, 243 (8%) were readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Table 2 presents sample characteristics. Concerning clinical variables for the 2 years prior to the ED visit leading to index hospitalization, 55% of patients had common MD (depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, adjustment disorders), 58% serious MD (schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders), and 25% SRD. Forty-five percent were diagnosed with chronic physical illnesses, yet severity levels were low in 65% of cases (index 0), according to the Elixhauser comorbidity index. Co-occurring SRD/chronic physical illnesses were identified for 17% of patients. Thirty-three percent presented with suicide ideation and 11% with suicide attempt. Six percent visited ED for violent behavior and 2% for social issues. Before hospitalization, most patients (40%) presenting at ED were registered at illness acuity level 3 (urgent).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients with Mental Disorders (MD) Hospitalized in 2014 to 2015 for any Medical Reason (Index Hospitalization) and Who Were Readmitted/Not Readmitted within 30 Days of Discharge.

| Characteristics Overall |

Total (Hospitalized Patients) | Readmitted within 30 Days | Not Readmitted within 30 Days | P | Standardized Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| 2,954 (100) | 243 (100) | 2,711 (100) | |||

| Clinical variables (2012 to 2014) | |||||

| Mental disorders (MD)a | |||||

| Common MD | 1,629 (55.1) | 141 (58.0) | 1,488 (54.9) | 0.191 | 0.063 |

| Depressive disorders | 909 (30.8) | 79 (32.5) | 830 (30.6) | 0.293 | 0.041 |

| Anxiety disorders | 1,145 (38.8) | 105 (43.2) | 1,040 (38.4) | 0.079 | 0.098 |

| Adjustment disorders | 659 (22.3) | 77 (31.7) | 582 (21.5) | 0.000 | 0.232 |

| Serious MD | 1,719 (58.2) | 157 (64.6) | 1,562 (57.6) | 0.020 | 0.144 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders | 1,248 (42.2) | 112 (46.1) | 1,136 (41.9) | 0.116 | 0.085 |

| Bipolar disorders | 884 (29.9) | 90 (37.0) | 794 (29.3) | 0.008 | 0.164 |

| Personality disorders | 524 (17.7) | 48 (19.8) | 476 (17.6) | 0.219 | 0.056 |

| Substance-related disorders (SRD; drug and alcohol) | 750 (25.4) | 85 (35.0) | 665 (24.5) | 0.001 | 0.231 |

| Alcohol-related disorders | 467 (15.8) | 45 (18.5) | 422 (15.6) | 0.133 | 0.077 |

| Drug-related disorders | 418 (14.2) | 41 (16.9) | 377 (13.9) | 0.121 | 0.083 |

| Reasons for emergency department (ED) visit related to index hospitalization | |||||

| Violent behavior or social issues | 253 (8,6) | 19 (7,8) | 234 (8,6) | 0.386 | 0.029 |

| Suicidal ideation | 894 (33.0) | 87 (35.8) | 981 (33.2) | 0.204 | 0.055 |

| Suicide attempt | 319 (10.8) | 29 (11.9) | 290 (10.7) | 0.307 | 0.038 |

| Chronic physical illnesses | 1,340 (45.4) | 121 (49.8) | 1,219 (45.0) | 0.084 | 0.096 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity indexb | 0.097 | 0.160 | |||

| 0 | 1,912 (64.7) | 141 (58.0) | 1,771 (65.3) | ||

| 1 | 318 (10.8) | 33 (13.6) | 285 (10.5) | ||

| 2 | 238 (8.1) | 26 (10.7) | 212 (7.8) | ||

| 3+ | 486 (16.5) | 43 (17.7) | 443 (16.3) | ||

| Co-occurring SRD/chronic physical illnesses | 513 (17.4) | 79 (32.5) | 434 (16.0) | 0.000 | 0.392 |

| Illness acuity (triage priority levels) (measured during ED visit leading to index hospitalization) | 0.688 | 0.060 | |||

| Level 1 and 2 (immediate and very urgent care) | 622 (21.1) | 48 (19.8) | 574 (21.2) | ||

| Level 3 (urgent care) | 1,189 (40.3) | 104 (42.8) | 1,085 (40.0) | ||

| Levels 4 and 5 (less urgent and nonurgent care) | 1,143 (38.7) | 91 (37.4) | 1,052 (38.8) | ||

| Sociodemographic variables (2014 to 2015) | |||||

| Age | 0.709 | 0.090 | |||

| 12 to 17 years | 119 (4.0) | 11 (4.5) | 108 (4.0) | ||

| 18 to 24 years | 339 (11.5) | 30 (12.3) | 309 (11.4) | ||

| 25 to 44 years | 1,064 (36.1) | 82 (33.7) | 982 (36.3) | ||

| 45 to 64 years | 981 (33.3) | 77 (31.7) | 904 (33.4) | ||

| 65+ years | 444 (15.1) | 43 (17.7) | 401 (14.8) | ||

| Sex | 0.238 | 0.052 | |||

| Male | 1,408 (47.7) | 110 (45.3) | 1,298 (47.8) | ||

| Female | 1,546 (52.3) | 133 (54.7) | 1,413 (52.1) | ||

| Material deprivation index | 0.080 | 0.210 | |||

| 1: Least deprived | 580 (19.6) | 38 (15.6) | 542 (20.0) | ||

| 2 | 411 (13.9) | 24 (9.9) | 387 (14.3) | ||

| 3 | 516 (17.5) | 41 (16.9) | 475 (17.5) | ||

| 4 | 514 (17.4) | 47 (19.3) | 467 (17.2) | ||

| 5: Most deprived | 590 (20.0) | 57 (23.5) | 533 (19.7) | ||

| Not assignedc | 343 (11.6) | 36 (14.8) | 307 (11.3) | ||

| Social deprivation index | 0.474 | 0.140 | |||

| 1: Least deprived | 301 (10.2) | 18 (7.4) | 283 (10.4) | ||

| 2 | 277 (9.4) | 22 (9.1) | 255 (9.4) | ||

| 3d | 361 (12.2) | 29 (11.9) | 332 (12.2) | ||

| 4 | 655 (22.2) | 52 (21.4) | 603 (22.2) | ||

| 5: Most deprived | 1,017 (34.4) | 86 (35.4) | 931 (34.3) | ||

| Not assignedc | 343 (11.6) | 36 (14.8) | 307 (11.3) | ||

| Quebec health regions (where inpatient units are located) | 0.01 | 0.172 | |||

| University regionsd | 2,367 (80.1) | 187 (77.0) | 2,180 (80.4) | ||

| Peripheral regions | 474 (16.0) | 38 (15.6) | 436 (16.1) | ||

| Other (intermediary and remote health regions) | 113 (3.8) | 18 (7.4) | 95 (3.5) | ||

| Service use variables | |||||

| Having a family physician (ED visit leading to index hospitalization) | 1,430 (48.4) | 115 (47.3) | 1,315 (48.5) | 0.388 | 0.024 |

| Health service use (measured 12 months before index hospitalization) | |||||

| Number of consultations with the patient general practitioner (GP) in private clinics or local community health service centers for any medical reason (GP most frequently consulted) | 0.306 | 0.100 | |||

| 0 consultations | 732 (24.8) | 70 (28.8) | 662 (24.4) | ||

| 1 to 3 consultations | 1,049 (35.5) | 80 (32.90) | 969 (35.7) | ||

| 4+ consultations | 1,173 (39.7) | 93 (38.3) | 1,080 (39.8) | ||

| Number of different GP consulted in primary care | 0.315 | 0.100 | |||

| 0 GP | 732 (24.8) | 70 (28.8) | 662 (24.4) | ||

| 1 to 3 GP | 1,431 (48.4) | 112 (3.8) | 1,319 (48.7) | ||

| 4+ GP | 791 (26.8) | 61 (25.1) | 730 (26.9) | ||

| Number of outpatient consultations with the patient psychiatrist (psychiatrist most frequently consulted) | 0.021 | 0.190 | |||

| 0 consultation | 576 (19.5) | 35 (14.9) | 541 (20.0) | ||

| 1 to 3 consultations | 1,385 (46.9) | 109 (44.9) | 1,276 (47.1) | ||

| 4+ consultationsd | 993 (33.6) | 99 (40.7) | 894 (33.0) | ||

| Number of different physicians consulted in specialized care | 0.500 | 0.080 | |||

| 0 physicians | 504 (17.1) | 35 (14.4) | 469 (17.3) | ||

| 1 to 3 physicians | 2,226 (75.4) | 188 (77.4) | 2,038 (75.2) | ||

| 4+ physiciansd | 224 (7.6) | 20 (8.2) | 204 (7.5) | ||

| Main medical provider | 0.062 | 0.150 | |||

| GP only | 488 (16.5) | 31 (12.8) | 457 (16.9) | ||

| Psychiatrist only | 644 (21.8) | 66 (27.2) | 578 (21.3) | ||

| Both GP and psychiatrist | 1,734 (58.7) | 142 (58.4) | 1,592 (58.7) | ||

| None | 88 (3.0) | 4 (1.6) | 84 (3.1) | ||

| Number of interventions at local community health service centers including GP consultations | 0.478 | 0.080 | |||

| 0 interventions | 1,414 (47.9) | 118 (48.6) | 1,296 (47.8) | ||

| 1 to 3 interventions | 582 (19.7) | 41 (16.9) | 541 (20.0) | ||

| 4+ interventions | 958 (32.4) | 84 (34.6) | 874 (32.2) | ||

| Prior ED visits for any medical reasons | 0.012 | 0.230 | |||

| 0 visits | 913 (30.9) | 65 (26.7) | 846 (31.3) | ||

| 1 to 3 visits | 951 (32.2) | 67 (27.6) | 884 (32.6) | ||

| 4+ visitsd | 1,090 (36.9) | 111 (45.7) | 979 (36.1) | ||

| Prior hospitalizations for any medical reason | 1,339 (45.3) | 150 (61.7) | 1,189 (43.9) | 0.000 | 0.362 |

| Number of inpatient days for index hospitalization for any medical reason | 0.000 | 0.520 | |||

| 1 to 3 daysd | 1,027 (34.8) | 107 (44.0) | 920 (33.9) | ||

| 4 to 7 days | 354 (12.0) | 32 (13.2) | 322 (11.9) | ||

| 8 to 15 days | 442 (15.0) | 44 (18.1) | 398 (14.7) | ||

| 16 to 29 daysd | 588 (19.9) | 11 (4.5) | 577 (21.3) | ||

| 30+ days | 543 (18.4) | 49 (20.2) | 494 (18.2) | ||

| Physician consultations for any medical reason after discharge from index hospitalization (measured within 30 days after discharge from index hospitalization or before readmission date) | 604 (20.4) | 20 (8.2) | 584 (21.5) | 0.000 | 0.381 |

a Participant can have more than one mental disorder. Therefore, the percent may exceed 100%.

b Chronic physical illnesses included: chronic pulmonary disease, cardiac arrhythmias, tumor without metastasis, renal disease, fluid electrolyte disorders, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, metastatic cancer, dementia, stroke, neurological disorders, liver disease, pulmonary circulation disorders, coagulopathy, weight loss, paralysis, AIDS/HIV.

c This is related to missing address or living in an area where index assignment is not feasible. An index cannot usually be assigned to residents of long-term health care units or when patients are homeless.

d This indicates significant differences at P < 0.10 Comparisons were provided (χ2) for each row reporting percentages for categorical variables.

Regarding sociodemographic variables, most patients (36%) were between 25 and 44 years of age, and 52% were female. Material deprivation levels varied little. However, 68% of patients lived in the most socially deprived area (4 to 5) or areas not assigned. Eighty percent were hospitalized in university health regions.

Regarding service use variables, 48% of patients reported having a family physician. In the 12 months prior to index hospitalization, 36% of patients had 1 to 3 consultations with the same GP in primary care, 40% had 4+, and 25% had none. Regarding primary care medical consultations in general, 48% had seen 1 to 3 different GP, and 27% 4+. Of the 81% who consulted their outpatient psychiatrist, 47% had 1 to 3 consultations, and 34% had 4+. In terms of specialized care provision, 75% were seen by 1 to 3 different medical specialists, and 8% by 4+. Nearly 59% of patients had been seen by both a GP and a psychiatrist 12 months prior to index hospitalization, 16% by GP only and 22% by psychiatrist only (3% by neither). Nearly half (48%) of patients did not consult local community health service centers; 32% visited ED 1 to 3 times, and 37% 4+ times, while 45% had prior hospitalizations for any medical reason. At the index hospitalization, 35% of patients were hospitalized for 1 to 3 days, 12% for 4 to 7 days, 15% for 8 to 15 days, 20% for 16 to 29 days, and 18% for 30+ days. Within the 30-day period before readmission, 20% of patients consulted a physician for any medical reason. Independent variables significantly associated with frequency of readmission within 30 days of the index hospital discharge in the bivariate analyses are also presented in Table 2.

Table 3 presents results for the hierarchical binary logistic (multivariate) regression. Concerning clinical variables (first model), patients with adjustment disorders, serious MD, or co-occurring SRD/chronic physical illnesses were more likely to be readmitted early. These variables remained significant in the final model. Adding sociodemographic variables (Model 2) revealed that patients hospitalized within 30 days of discharge were more likely to be hospitalized in health regions other than those with university-affiliated hospitals. However, with further introduction of service use variables (Model 3), the significant associations for health regions disappeared. In terms of service use variables, patients who consulted the same outpatient psychiatrist 4 times+ and were hospitalized for any medical reason in the 12 months prior to index hospitalization were more likely to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Those who made 1 to 3 ED visits in the 12 months before the index hospitalization remained in hospital 16 to 29 days during the index hospitalization, and those who consulted a physician for any medical reason within a 30-day period after discharge or prior to readmission were less likely to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Clinical variables accounted for 52% of the total variance explained in the model, while service use variables contributed for 42% and sociodemographic variables 6%.

Table 3.

Predictors of 30-day Hospital Readmission for Patients with Mental Disorders Hospitalized for Any Medical Reason (Index Hospitalization in 2014 to 2015).

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 3a | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | P Value | OR | 95% CI | β | P Value | OR | 95% CI | β | P Value | OR | 95% CI |

| Clinical variables (2012 to 2014) | ||||||||||||

| Mental disorders (MD) | ||||||||||||

| Adjustment disorders | 0.559 | 0.000 | 1.74 | 1.304 to 2.344 | 0.532 | 0.000 | 1.703 | 1.268 to 2.287 | 0.417 | 0.010 | 1.517 | 1.105 to 2.084 |

| Serious MD | 0.658 | 0.000 | 1.93 | 1.441 to 2.589 | 0.637 | 0.000 | 1.891 | 1.404 to 2.548 | 0.496 | 0.003 | 1.642 | 1.184 to 2.276 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity indexb | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 0.257 | 0.221 | 1.293 | 0.857 to 1.953 | 0.268 | 0.206 | 1.307 | 0.863 to 1.978 | 0.221 | 0.307 | 1.247 | 0.817 to 1.904 |

| 2 | 0.151 | 0.520 | 1.163 | 0.735 to 1.840 | 0.178 | 0.449 | 1.195 | 0.753 to 1.897 | 0.136 | 0.578 | 1.146 | 0.709 to 1.850 |

| 3+ | −0.091 | 0.634 | 0.913 | 0.623 to 1.327 | −0.051 | 0.788 | 0.950 | 0.652 to 1.383 | −0.178 | 0.378 | 0.837 | 0.563 to 1.244 |

| Co-occurring substance-related disorders (SRD)/chronic physical illnesses | 1.345 | 0.000 | 3.838 | 2.889 to 5.09 | 1.345 | 0.000 | 3.838 | 2.878 to 5.118 | 1.368 | 0.000 | 3.923 | 2.912 to 5.299 |

| Sociodemographic variables (2014 to 2015) | ||||||||||||

| Material deprivation index | ||||||||||||

| 2 | −0.135 | 0.625 | 0.874 | 0.509 to 1.500 | −0.119 | 0.670 | 0.887 | 0.512 to 1.537 | ||||

| 3 | 0.314 | 0.138 | 1.368 | 0.904 to 2.071 | 0.234 | 0.278 | 1.264 | 0.828 to 1.929 | ||||

| 4 | 0.274 | 0.239 | 1.316 | 0.833 to 2.078 | 0.232 | 0.329 | 1.262 | 0.792 to 2.011 | ||||

| 5 | 0.317 | 0.160 | 1.373 | 0.882 to 2.137 | 0.225 | 0.330 | 1.253 | 0.796 to 1.970 | ||||

| Quebec health regions (measured at the index hospitalization) (ref.: university region) | ||||||||||||

| Periphery | −0.058 | 0.765 | 0.943 | 0.644 to 1.382 | −0.076 | 0.702 | 0.927 | 0.628 to 1.367 | ||||

| Other (intermediary and remote health regions) | 0.702 | 0.012 | 2.017 | 1.163 to 3.499 | 0.557 | 0.057 | 1.745 | 0.984 to 3.094 | ||||

| Service use variables | ||||||||||||

| Health service use (measured 12 months before index hospitalization) | ||||||||||||

| Number of outpatient consultations with the patient psychiatrist (ref.: 0) | ||||||||||||

| 1 to 3 consultations | . | 0.340 | 0.120 | 1.405 | 0.915 to 2.157 | |||||||

| 4+ consultations | 0.613 | 0.007 | 1.847 | 1.181 to 2.886 | ||||||||

| Prior emergency department (ED) visits for any medical reason (ref.: 0) | ||||||||||||

| 1 to 3 visits | –0.414 | 0.046 | 0.661 | 0.440 to 0.992 | ||||||||

| 4+ visits | −0.389 | 0.076 | 0.678 | 0.441 to 1.041 | ||||||||

| Prior hospitalizations for any medical reason | 0.603 | 0.001 | 1.827 | 1.283 to 2.602 | ||||||||

| Number of inpatient days for index hospitalization for any medical reason (ref.:1 to 3 days) | ||||||||||||

| 4 to 7 days | −0.289 | 0.143 | 0.749 | 0.509 to 1.103 | ||||||||

| 8 to 15 days | −0.050 | 0.805 | 0.951 | 0.640 to 1.414 | ||||||||

| 16 to 29 days | −1.867 | 0.000 | 0.155 | 0.081 to 0.295 | ||||||||

| 30+ days | −0.289 | 0.143 | 0.749 | 0.509 to 1.103 | ||||||||

| Physician consultations for any medical reason after hospital discharge (measured within 30 days after discharge at index hospitalization or before readmission date) | −1.100 | 0.000 | 0.333 | 0.206 to 0.538 | ||||||||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow test | ||||||||||||

| χ2 | 6.902 | 5.953 | 9.828 | |||||||||

| df | 6 | 8 | 8 | |||||||||

| P | 0.330 | 0.653 | 0.277 | |||||||||

a Adjusted logistic regression models.

b Chronic physical illnesses included chronic pulmonary disease, cardiac arrhythmias, tumor without metastasis, renal disease, fluid electrolyte disorders, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, metastatic cancer, dementia, stroke, neurological disorders, liver disease, pulmonary circulation disorders, coagulopathy, weight loss, paralysis, AIDS/HIV.

Discussion

The study results showed that 8% of patients were readmitted within 30 days of hospital discharge, falling in the “5% to 15%” or low range as established in previous studies on early readmission after discharge for patients with MD.6,15,16 Results did not confirm our hypothesis that early hospital readmission would be most strongly associated with service use variables. Clinical variables contributed most to the total variance in the final model but closely followed by service use variables. Sociodemographic variables were weakly associated with early readmission, as in most previous studies that included variables such as age7,11 and sex.6,29

Results related to clinical variables indicated a key association between early readmission and illness severity. Co-occurring SRD/physical illnesses were the strongest variables associated with early readmission for patients with MD. This was logical as studies often describe these patients as frequent users of ED and inpatient hospital services.48,49 Early readmission may have resulted from the absence of integrated MD/SRD services,50 difficulty accessing ambulatory care,51 or stigmatization from health care professionals.52 Some studies also found that patients with substance misuse53 or drug use disorders34 often have difficulty accessing addiction treatment. Yet, it is possible that some patients were reluctant to use these services, as studies often show.53 Overall, few services are available for patients with SRD in either community or hospital settings.50,54 The implementation of SRD liaison nurses in ED50 and integrated treatment55 may help the screening of such patients and their coordination with appropriate services. Moreover, chronic physical illnesses (e.g., pulmonary disease, neurological disorders, liver disease) complicate treatment, reduce life expectancy and promote higher use of acute care, increasing the risks of readmission for patients with MD and/or SRD.19,34,56 Collaborative care between MH services and primary care would be particularly appropriate for this clientele experiencing multiple health problems.57 The association between early readmission and serious MD was previously reported.7,16,27 One explanation may be that patients with serious MD may have problems with medication adherence.7 They also may not receive adequate support from services or from their families after discharge, increasing risks of rehospitalization.7 Patients with serious MD need expedited access to care and intensive follow-up, as offered by assertive community treatment, intensive case management teams or day hospitals58 to avoid readmission. The association between adjustment disorders and early readmission has rarely been observed. Yet, adjustment disorders are a frequent diagnosis among patients at first hospitalization, mainly among adolescents or young adults; and for some, the diagnosis may change at rehospitalization.59,60 As well, adjustment disorders are strongly associated with repeated suicidal behaviors, which may explain the high prevalence of affected patients in acute care hospital services.61,62 For this common MD, brief psychological interventions may be the most appropriate treatment.63

Results on service use variables also demonstrated a systemic deficit in access to and continuity of care among study participants readmitted early. Among service use variables positively associated with early readmission, previous hospitalization was strongest, which coincides with results in previous studies related to psychiatric hospitalization.11,25,64 However, our study also included previous hospitalization for medical reasons other than MD. The association between having 4+ outpatient consultations with patient psychiatrist before the index hospitalization and readmission within 30 days of discharge contradicts previous research claiming that greater access to outpatient services helped reduce the risk of frequent ED use or readmissions.65 However, most studies did not control for frequency of visits, suggesting that the intensity of previous outpatient consultations or quality of care (e.g., type of treatment) may have been inadequate to meet patient needs, contributing to readmissions. This also confirms the great severity of psychiatric symptoms experienced by patients with 4+ outpatient consultations. Patients making frequent psychiatric consultations tend to be those with more complex or serious MD and co-occurring health and social problems,66,67 whose needs are often characterized as unmet,68–70 and requiring very intensive, fully integrated biopsychosocial care.70,71

Patients having 1 to 3 prior 12-month ED visits were identified as less likely to be readmitted early. It may be that these patients, known to ED and specialized services, were provided with more intensive care that prevented readmission as well as their risk of becoming high ED users. Previous Quebec MH or SRD reforms reinforced programs such as assertive community treatment, intensive case management,72 home treatment teams,73 SRD liaison model at ED,50,74 and community-based crisis interventions,75 all of which are known to reduce ED visits and hospitalizations. Our results also demonstrated that patients hospitalized 16 to 29 days were less likely to be readmitted early, as compared to those hospitalize 1 to 3 days. While not a significant finding, this trend seems reversed for those hospitalized 30+ days. In general, patients with MD discharged after longer stays were found in previous studies to have more stable conditions28 and were less likely to be readmitted.6,28,29,76 However, hospitalizations exceeding 30 days is also considered an indicator of inadequate quality of care.77 Finally, results show that physician consultation for any medical reason within 30 days of discharge was negatively associated with readmission. Studies recommend that physician consultations should occur within the first 10 to 21 days,78 or at least within the first 30 days of discharge,13,79 in order to have a protective effect. Previous studies also found that the risk of early readmission increased when patients did not attend their first outpatient consultation12 or when consultations were not scheduled soon after discharge;9,79 the same was true for early return to ED following discharge.80

Limitations

This study had certain limitations. First, administrative databanks were primarily developed for financial purposes and not for research. They thus represent a proxy for patient service use and clinical conditions. Second, some key data such as race/ethnicity, medication compliance, health care professional use other than physicians, community-based services, or collaborative care that may have shown associations with early readmission were not available from Quebec databanks. Finally, results may be not generalizable to all hospitalized patients with MD, particularly in settings more outside university health regions and with health care systems without universal coverage.

Conclusions

Drawing on variables not previously analyzed, this study determined that readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge among patients with MD was more strongly associated with clinical variables, mainly co-occurring SRD/chronic physical illnesses and serious MD, which reflects the limits of health care services to treat patients with the most serious mental and physical health conditions. However, several service use variables were identified that may play a key role in preventing early readmission and should be prioritized in health policy and service planning. Thus, this study demonstrated the importance of ensuring a sufficiently long hospital stay (from 16 to 29 days) before discharge, and the benefit of consultations soon after discharge for avoiding early readmission. Results also show the usefulness of developing specific interventions for patients at high risk of readmission. SRD liaison nurse at the ED, integrated treatment, and collaborative care might be more widely deployed to facilitate treatment and follow-up for patients affected by co-occurring SRD and chronic physical illnesses. Best practices such as assertive community treatment, intensive case management, day hospital or home treatment, and community-based crisis services may be further harnessed for patient follow-up among those with serious MD. For adjustment disorders, brief psychological interventions are recommended. Overall, increased adequacy of access to health services and continuity of care before and after hospital discharge, including better discharge planning, would likely prevent early hospital readmission and should be more widely prioritized in future MH action plans.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Canadian Institutes of health Research (CIHR).We would also like to thank the the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (FRQ-S) for awarding a postdoctoral fellowship to the first author. We would also like to thank Judith Sabetti for editorial assistance.

Authors’ Note: The data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of health Research (CIHR; Grant Number 8400997).

ORCID iD: Marie-Josée Fleury, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4743-8611

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4743-8611

References

- 1. Hermann RC, Mattke S, Somekh D, et al. Quality indicators for international benchmarking of mental health care. IInt J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(Suppl 1):31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Byrne SL, Hooke GR, Page AC. Readmission: a useful indicator of the quality of inpatient psychiatric care. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(1-2):206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zilber N, Hornik-Lurie T, Lerner Y. Predictors of early psychiatric rehospitalization: a national case register study. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(1):49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vigod SN, Taylor VH, Fung K, et al. Within-hospital readmission: an indicator of readmission after discharge from psychiatric hospitalization. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(8):476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heslin KC, Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Hospitalizations involving mental and substance use disorders among adults. Statistical Brief 191. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barker LC, Gruneir A, Fung K, et al. Predicting psychiatric readmission: sex-specific models to predict 30-day readmission following acute psychiatric hospitalization. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(2):139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moore CO, Moonie S, Anderson J. Factors associated with rapid readmission among Nevada state psychiatric hospital patients. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55(5):804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lien L. Are readmission rates influenced by how psychiatric services are organized? Nord J Psychiatry. 2002;56(1):23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reddy M, Schneiders-Rice S, Pierce C, et al. Accuracy of prospective predictions of 30-day hospital readmission. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(2):244–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mark TL, Tomic KS, Kowlessar N, et al. Hospital readmission among Medicaid patients with an index hospitalization for mental and/or substance use disorder. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2013;40(2):207–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Durbin J, Lin E, Layne C, et al. Is readmission a valid indicator of the quality of inpatient psychiatric care? J Behav Health Serv Res. 2007;34(2):137–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Habit NF, Johnson E, Edlund BJ. Appointment reminders to decrease 30-day readmission rates to inpatient psychiatric hospitals. Prof Case Manag. 2018;23(2):70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor C, Holsinger B, Flanagan JV, et al. Effectiveness of a brief care management intervention for reducing psychiatric hospitalization readmissions. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2016;43(2):262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shaffer SL, Hutchison SL, Ayers AM, et al. Brief critical time intervention to reduce psychiatric rehospitalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(11):1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rieke K, McGeary C, Schmid KK, et al. Risk factors for inpatient psychiatric readmission: are there gender differences? Community Ment Health J. 2016;52(6):675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ortiz G. Predictors of 30-day postdischarge readmission to a multistate national sample of state psychiatric hospitals. J Healthc Qual. 2019;41(4):228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. OECD. Unplanned hospital re-admissions for patients with mental disorders. Health at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, 2013doi: 10.1787/19991312. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burke RE, Donze J, Schnipper JL. Contribution of psychiatric illness and substance abuse to 30-day readmission risk. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davydow DS, Ribe AR, Pedersen HS, et al. Serious mental illness and risk for hospitalizations and rehospitalizations for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in Denmark: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Med Care. 2016;54(1):90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Freedland KE, Carney RM, Rich MW, et al. Depression and multiple rehospitalizations in patients with heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(5):257–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iyer AS, Bhatt SP, Garner JJ, et al. Depression is associated with readmission for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(2):197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ahmedani BK, Solberg LI, Copeland LA, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, AMI, and pneumonia . Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(2):134–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Appleby L, Luchins DJ, Desai PN, et al. Length of inpatient stay and recidivism among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(9):985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boaz TL, Becker MA, Andel R, et al. Risk factors for early readmission to acute care for persons with schizophrenia taking antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(12):1225–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schmutte T, Dunn CL, Sledge WH. Predicting time to readmission in patients with recent histories of recurrent psychiatric hospitalization: a matched-control survival analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(12):860–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamilton JE, Passos IC, de Azevedo Cardoso T, et al. Predictors of psychiatric readmission among patients with bipolar disorder at an academic safety-net hospital. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(6):584–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vijayaraghavan M, Messer K, Xu Z, et al. Psychiatric readmissions in a community-based sample of patients with mental disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(5):551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Figueroa R, Harman J, Engberg J. Use of claims data to examine the impact of length of inpatient psychiatric stay on readmission rate. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(5):560–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vigod SN, Kurdyak P, Fung K, et al. Psychiatric hospitalizations: a comparison by gender, sociodemographics, clinical profile, and postdischarge outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(12):1376–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lyons JS, Stutesman J, Neme J, et al. Predicting psychiatric emergency admissions and hospital outcome. Med Care. 1997;35(8):792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mojtabai R, Nicholson RA, Neesmith DH. Factors affecting relapse in patients discharged from a public hospital: results from survival analysis. Psychiatr Q. 1997;68(2):117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Donisi V, Tedeschi F, Salazzari D, et al. Pre- and post-discharge factors influencing early readmission to acute psychiatric wards: implications for quality-of-care indicators in psychiatry. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vigod SN, Kurdyak PA, Seitz D, et al. READMIT: a clinical risk index to predict 30-day readmission after discharge from acute psychiatric units. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;61:205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Becker MA, Boaz TL, Andel R, et al. Risk of early rehospitalization for non-behavioral health conditions among adult medicaid beneficiaries with severe mental illness or substance use disorders. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(1):113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Busch AB, Epstein AM, McGuire TG, et al. Thirty-day hospital readmission for medicaid enrollees with schizophrenia: the role of local health care systems. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2015;18(3):115–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Swett C. Symptom severity and number of previous psychiatric admissions as predictors of readmission. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46(5):482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Callaly T, Trauer T, Hyland M, et al. An examination of risk factors for readmission to acute adult mental health services within 28 days of discharge in the Australian setting. Australas Psychiatry. 2011;19(3):221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec. Rapport annuel de gestion, 2016-2017. Quebec, Canada: Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pampalon R, Hamel D, Gamache P, et al. A deprivation index for health planning in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 2009;29(4):178–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blais C, Jean S, Sirois C, et al. Quebec integrated chronic disease surveillance system (QICDSS), an innovative approach. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34(4):226–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. Canadian triage acuity scale. 2012. http://ctas-phctas.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/participant_manual_v2.5b_november_2013_0.pdf. Acessed: january 18, 2019

- 43. Dreiher J, Comaneshter DS, Rosenbluth Y, et al. The association between continuity of care in the community and health outcomes: a population-based study. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2012;1(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tousignant P, Diop M, Fournier M, et al. Validation of 2 new measures of continuity of care based on year-to-year follow-up with known providers of health care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):559–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Blonigen DM, Macia KS, Bi X, et al. Factors associated with emergency department use among veteran psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Q. 2017;88(4):721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huynh C, Ferland F, Blanchette-Martin N, et al. Factors influencing the frequency of emergency department utilization by individuals with substance use disorders. Psychiatr Q. 2016;87(4):713–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Buhumaid R, Riley J, Sattarian M, et al. Characteristics of frequent users of the emergency department with psychiatric conditions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(3):941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Doupe MB, Palatnick W, Day S, et al. Frequent users of emergency departments: developing standard definitions and defining prominent risk factors. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fleury MJ, Perreault M, Grenier G, et al. Implementing key strategies for successful network integration in the Quebec substance-use disorders programme. Int J Integr Care. 2016;16(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ayangbayi T, Okunade A, Karakus M, et al. Characteristics of hospital emergency room visits for mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(4):408–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Comparing stigmatising attitudes towards people with substance use disorders between the general public, GPs, mental health and addiction specialists and clients. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61(6):539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Borg B, Douglas IS, Hull M, et al. Alcohol misuse and outpatient follow-up after hospital discharge: a retrospective cohort study. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018;13(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF, et al. A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27(4):360–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Drake RE, Mercer-McFadden C, Mueser KT, et al. Review of integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for patients with dual disorders. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(4):589–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Abernathy K, Zhang J, Mauldin P, et al. Acute care utilization in patients with concurrent mental health and complex chronic medical conditions. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(4):226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bauer MS, Weaver K, Kim B, et al. The collaborative chronic care model for mental health conditions: from evidence synthesis to policy impact to scale-up and spread. Med Care. 2019;57(Suppl 10, Suppl 3):S221–S227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Addington D, Anderson E, Kelly M, et al. Canadian practice guidelines for comprehensive community treatment for schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(9):662–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Patra BN, Sarkar S. Adjustment disorder: current diagnostic status. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(1):4–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Greenberg WM, Rosenfeld DN, Ortega EA. Adjustment disorder as an admission diagnosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(3):459–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gradus JL, Qin P, Lincoln AK, et al. The association between adjustment disorder diagnosed at psychiatric treatment facilities and completed suicide. Clin Epidemiol. 2010;2:23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fegan J, Doherty AM. Adjustment disorder and suicidal behaviours presenting in the general medical setting: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(16):2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Casey P, Bailey S. Adjustment disorders: the state of the art. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Appleby L, Desai P. Residential instability: a perspective on system imbalance. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57(4):515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hamilton JE, Desai PV, Hoot NR, et al. Factors associated with the likelihood of hospitalization following emergency department visits for behavioral health conditions. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(11):1257–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tulloch AD, Fearon P, David AS. Length of stay of general psychiatric inpatients in the United States: systematic review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(3):155–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fleury MJ, Fortin M, Rochette L, et al. Assessing quality indicators related to mental health emergency room utilization. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Walker ER, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, et al. Insurance status, use of mental health services, and unmet need for mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(6):578–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Werner S. Needs assessment of individuals with serious mental illness: can it help in promoting recovery? Community Ment Health J. 2012;48(5):568–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Croft B, Parish SL. Care integration in the patient protection and affordable care act: implications for behavioral health. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(4):258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Druss BG, Mauer BJ. Health care reform and care at the behavioral health—primary care interface. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(11):1087–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux. Faire ensemble et autrement. Plan d’action en santé mentale 2015-2020. Quebec, Canada: Ministère de la Santé et des services sociaux, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Boisvert A, Bouffard A-P, Paquet K. Le traitement intensif bref à domicile. Santé Mentale. 2016;204:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lecavalier M, Fleury M-J, Couillard J, et al. Les équipes de liaison en dépendance au CRDM-IU: l’indispensable pont entre l’hôpital et la réadaptation. Le Point en administration de la santé et des services sociaux. 2014;10(1):48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Guo S, Biegel DE, Johnsen JA, et al. Assessing the impact of community-based mobile crisis services on preventing hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(2):223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Brennan PL, Kagay CR, Geppert JJ, et al. Elderly Medicare inpatients with substance use disorders: characteristics and predictors of hospital readmissions over a four-year interval. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(6):891–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Johnstone P, Zolese G. Systematic review of the effectiveness of planned short hospital stays for mental health care. BMJ. 1999;318(7195):1387–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Riverin BD, Strumpf EC, Naimi AI, et al. Optimal timing of physician visits after hospital discharge to reduce readmission. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4682–4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cuffel BJ, Held M, Goldman W. Predictive models and the effectiveness of strategies for improving outpatient follow-up under managed care. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(11):1438–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. McCullumsmith C, Clark B, Blair C, et al. Rapid follow-up for patients after psychiatric crisis. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51(2):139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]