Abstract

Short note

Dengue fever and dengue haemorrhagic fever are two of the most important mosquito-borne viral diseases of public health significance [1, 2]. Their geographical spread is increasing: while only 5 countries documented dengue cases in the 1950s, more than 100 countries reported the incidence of dengue fever and dengue haemorrhagic fever in 2005 [3]. In Cambodia, since the massive epidemic in 1995, accounting for more than 400 deaths, the number of cases has been monitored every year [4, 5]. Major dengue epidemics outbreaks happened in 2007 (39,618 cases with 396 deaths), 2012 (42,362 cases with 189 deaths) and 2019 (68,597 cases with 48 deaths) (Ministry of Health, Phnom Penh, Cambodia). In 2018 and 2019, the capital Phnom Penh city was terribly affected as never before with respectively 9445 and 9298 cases (Ministry of Health, Phnom Penh, Cambodia).

Hosting about 2.13 million of the 15.3 million inhabitants of Cambodia, Phnom Penh is a rapidly developing city [6]. The multiple potential mosquito breeding sites created in the urban centre can favour vector proliferation, particularly dengue vectors [7].

The two main mosquito species responsible for the transmission of dengue virus are Aedes aegypti (Linnée, 1789) and Aedes albopictus (Skuse, 1894) [8–10]. The latter species, originating from the forests of Southeast Asia, where it was likely zoophilic (i.e. feeding on wildlife), progressively adapted to anthropogenic changes to the environment, which provided alternative blood sources (domestic animals and humans) and water collections for larval habitats [9, 11]. This species is a competent vector for all four serotypes of dengue and can transmit at least 22 arboviruses [9, 12]. Human migration favoured its spread into new areas, and it rapidly became an opportunistic container breeder, using either natural or artificial containers, having the ability to survive in small collections of water in tires, plastic buckets, and plastic cups. Today, it mainly occurs in suburban and rural areas [9].

While Ae. albopictus is known to originate from Southeast Asia, and known from Cambodia [13], its presence was never attested in the capital city. In 1966, its presence was declared in the rural part of Chrui Chang War, a district facing Phnom Penh, located on the eastern side of the Mekong River [14]. Despite the extensive work realised in the beginning of the 2000s [7, 13, 15, 16] in which the distribution, occurrence, and genetics of Ae. aegypti in the Cambodian capital were extensively studied, Ae. albopictus was never collected inside Phnom Penh itself (Paupy, personal communication 2020).

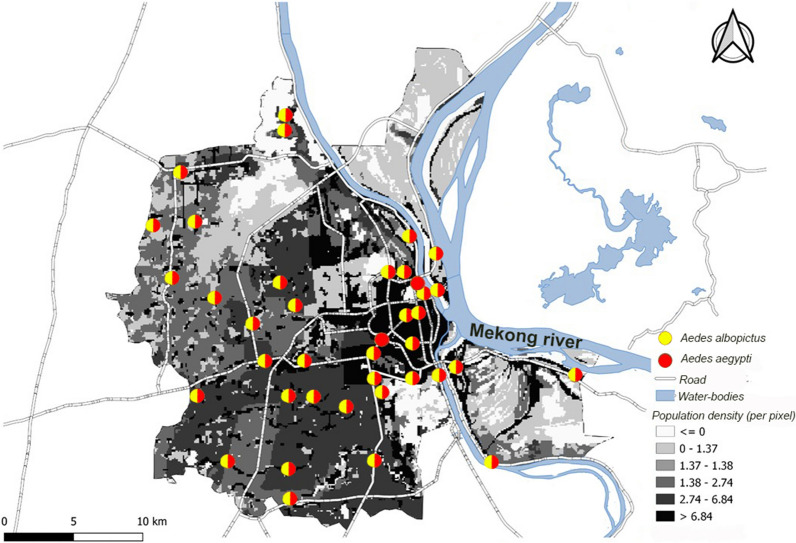

In 2019, an entomological survey was performed by the Medical and Veterinary Entomology Unit of the Institut Pasteur du Cambodge in 42 randomly distributed sites across Phnom Penh (Fig. 1). Each location was visited every 2 months. As expected, Ae. aegypti was found in all sites. Surprisingly, Ae. albopictus was found in 40 sites including urban areas. This result attests to its recent and massive installation and distribution throughout the entire city. Meanwhile, this spreading and establishment occurred not only in Phnom Penh, but also in tropical and temperate cities worldwide [17], demonstrating that a recent invasive population has emerged [18].

Fig. 1.

Location of the different sampling points in Phnom Penh (Cambodia) and presence of the two different species of Aedes: Ae albopictus and Ae. aegypti. Density data gathered from Open Development Cambodia. Map created via QGis.

Although Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus are competent vectors for dengue virus, it has been hypothesized that they might play different roles in contributing to a dengue outbreak. Ae. aegypti might initiate a cluster, leading to an outbreak, which could then be sustained by Ae. albopictus, expanding the scale of the virus propagation [8]. This observation made in Taiwan needs to be investigated in Phnom Penh, as does the temporal succession of each species locally.

Consequently, it is important to consider the ecology and seasonality of Ae. albopictus alongside that of Ae. aegypti when developing vector/disease control programs in Phnom Penh. This information is important for the Ministry of Health in Phnom Penh as evidence of the need to increase surveillance and control of this species in suburban and rural areas (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Supplementary Information

Additional file1: Table S1. Total number of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus collected in each trapping location inside Phnom Penh.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Institut Pasteur du Cambodge, who funded this internal project, as well as all the Medical and Veterinary Entomology Unit team members, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Authors' contributions

POM, DF, SB. Conceptualization: POM, DF, SB POM, DF, SB. Data curation: POM, DF, SB. Funding acquisition: DF, SB. Methodology: POM, DF, SB. Supervision: POM, DF, SB. Writting-original draft: POM, DF, SB. Writting-reviews and editing: POM, DF, SB. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by an internal funding of the Institut Pasteur du Cambodge. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are within the paper and its supporting information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13071-021-04633-5.

References

- 1.Gubler DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998;11(3):480–496. doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.3.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilder-Smith A, Ooi EE, Horstick O, Wills B. Dengue. Lancet. 2019;393(10169):350–363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guha-Sapir D, Schimmer B. Dengue fever: new paradigms for a changing epidemiology. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2005;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huy R, Buchy P, Conan A, Ngan C, Ong S, Ali R, Duong V, Yit S, Ung S, Te V, Chroeung N, Pheaktra NC, Uok V, Chroeung N. National dengue surveillance in Cambodia 1980–2008: epidemiological and virological trends and the impact of vector control. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010;88:650–657. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.073908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vong S, Khieu V, Glass O, Ly S, Duong V, Huy R, Ngan C, Wichman O, Letson GW, Margolis HS, Buchy P. Dengue incidence in urban and rural Cambodia: results from population-based active fever surveillance, 2006–2008. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(11):e903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Than C. General population census of the Kingdom of Cambodia 2019. Natl Inst Stat Minist Plan. 2019;53:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paupy C, Chantha N, Vazeille M, Reynes J-M, Rodhain F, Failloux A-B. Variation over space and time of Aedes aegypti in Phnom Penh (Cambodia): genetic structure and oral susceptibility to a dengue virus. Genet Mol Res. 2003;82:171–182. doi: 10.1017/S0016672303006463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang C-F, Hou J-N, Chen T-H, Chen W-J. Discriminable roles of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in establishment of dengue outbreaks in Taiwan. Acta Trop. 2014;130:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paupy C, Delatte H, Bagny L, Corbel V, Fontenille D. Aedes albopictus, an arbovirus vector: from the darkness to the light. Microbes Infect. 2009;11(14–15):1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Souza-Neto J, Powell JR, Bonizzoni M. Aedes aegypti vector competence studies: a review. Infect Genet Evol. 2019;67:191–209. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyer S, Foray C, Dehecq JS. Spatial and temporal heterogeneities of Aedes albopictus density in La Reunion Island: rise and weakness of entomological indices. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e91170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peirera-dos-Santos T, Roiz D, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, Paupy C. A systematic review : is Aedes albopictus an efficient birdge vector for zoonotic arboviruses ? Pathogens. 2020;9:266. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9040266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paupy C, Chantha N, Reynes JM, Failloux AB. Factors influencing the population structure of Aedes aegypti from the main cities in Cambodia. Heredity. 2005;95(2):144–147. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mouchet J, Chastel C. Resistance to insecticides in Aedes aegypti L. and Aedes albopictus in Phnom Penh (Cambodia) Med trop. 1966;26(5):505–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paupy C, Chantha N, Huber K, Lecoz N, Reynes JM, Rodhain F, Failloux A-B. Influence of breeding sites features on genetic differentiation of Aedes aegypti populations analyzed on a local scale in Phnom Penh Municipality of Cambodia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71(1):73–81. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2004.71.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paupy C, Orsoni A, Mousson L, Huber K. Comparisons of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), microsatellite, and isoenzyme markers: population genetics of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Phnom Penh (Cambodia) J Med Entomol. 2004;41(4):664–671. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreamer M, Sinka M, Duda K, Mylne A, Shearer F, Barker C, Moore C, Carvalho R, Coelho G, Van Bortel W, Hendrickx G, Schaffner F, Elyazar I, Teng H-J, Brady O, Messina J, Pigott D, Scott T, Smith D, Wint G, Golding N, Hay. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. eLife 2015;4:e08347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Delatte H, Bagny L, Brengue C, Bouetard A, Paupy C, Fontenille D. The invaders: Phylogeography of dengue and chikungunya viruses Aedes vectors, on the South West islands of the Indian Ocean. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11(7):1769–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file1: Table S1. Total number of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus collected in each trapping location inside Phnom Penh.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its supporting information files.