Abstract

Bronchoscopy, as an aerosol-generating procedure, is not routinely performed in patients with high-risk of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) owing to potential transmission to healthcare workers. However, to obtain lower respiratory specimens from bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is necessary to confirm COVID-19 or other diagnosis that will change clinical management. We report a case of diagnostic difficulty with five negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing in four upper respiratory tract and one stool samples following presentation with fever during the quarantine period and a strong epidemiological linkage to an index patient with COVID-19. The final diagnosis was confirmed by BAL. Special precautions to be taken when performing bronchoscopy in high-risk non-intubated patients were discussed.

Keywords: COVID-19, Bronchoscopy, Infection control

Case report

On 4 June 2020, a 33-year-old gentleman with good past health was transferred from a quarantine centre to the Prince of Wales Hospital with fever of 38 °C. He lived next door to an index case of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in a public housing.

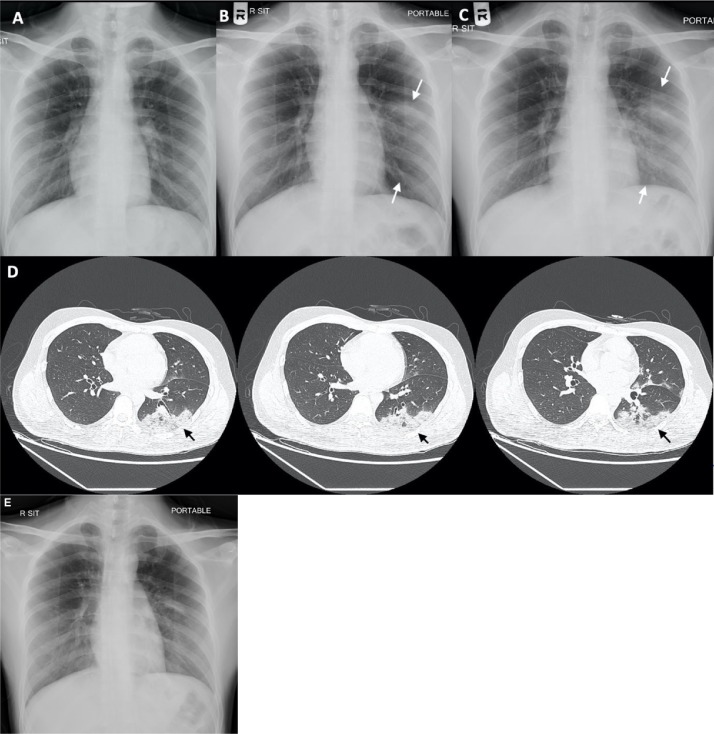

He had no chest nor other localising symptoms. On admission, physical examination results were normal except for temperature 38.2 °C. Blood tests revealed normal white cell count (WCC), lymphocyte count and C-reactive protein (CRP). Chest radiograph (CXR) showed clear lung field (Figure 1 A). Nasopharyngeal and throat swab (NPS/TS) taken for RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 (Lui et al., 2020) revealed negative results. He was kept under observation and no empirical antibiotics were given.

Figure 1.

A–C: Progressive left middle and lower zone infiltration on chest radiographs on admission (5 June), day 4 (8 June) and day 6 (10 June). D: Contrast CT Scan of Thorax on day 8 (12 June). E: Resolving left lower zone infiltration on CXR on day 11 (15 June).

However, his fever worsened on 8 June reaching 39 °C. CXR showed new consolidative change over the left middle zone (Figure 1B). His WCC remained normal but CRP rose from 2.1 to 5.2 mg/L. Repeated NPS/TS for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR was still negative. Urine Legionella and Pneumococcal antigens were both negative. No sputum could be saved. He was put on empirical amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and doxycycline for pneumonia.

Deep throat saliva and stool were sent for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR on 9 June and results were negative. However, the patient had persistent swinging fever, the infiltrate on CXR had extended to the left lower zone (Figure 1C) and the CRP rose to 27.3 mg/L. Therefore, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was changed to ceftriaxone on 10 June 2020.

Thorax contrast computerised tomography (CT) scan was performed on 12 June that showed mixed ground glass and consolidative changes in left lower and upper lobes, suggestive of pneumonic changes (Figure 1D).

Another NPS/TS was obtained on the same day for SARS-CoV-2 rapid RNA testing. The result was again negative. Bronchoscopy was done in a negative pressure room in an endoscopy centre using a reusable conventional bronchoscope through the nasal route under conscious sedation with 3 mg of midazolam and 40 mcg of fentanyl. The endoscopist and nursing assistants were wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), including N95 respirators, cap, face shield, gown and gloves. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was obtained from the left lower lobe. SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR of BAL was positive finally with a cycle threshold value of 24. He was started on lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra®) 200/50 two tablets twice daily and subcutaneous interferon beta-1b 8 million international units alternative days in the same evening.

The patient’s fever resolved since 13 June, and repeated CXR on 15 June showed improved left lower zone infiltrates (Figure 1E). NPS/TS and two DTS samples were taken on 16, 19 and 23 June for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR; all three samples were negative. He was discharged on 24 June.

Discussion

Diagnosis of COVID-19

This patient was suspected to have COVID-19 in view of fever with an epidemiological linkage to a cluster of confirmed cases, but repeated testing for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR from four upper respiratory tract (URT) and one stool samples were all negative. This is a rare condition. In a study of 70 patients in Singapore (Lee et al., 2020), 95.7% of patients had SARS-CoV-2 detected in their first two clinical specimens. Only 2 (2.9%) patients required more than four tests to detect the virus.

According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Guidelines (Hanson et al., 2020), nasopharyngeal (NP), mid-turbinate or nasal swabs are the preferred specimens for SARS-CoV-2 RNA testing in symptomatic individuals suspected of having COVID-19. The recommendation was based on 13 studies, which showed high sensitivity and specificity of these specimen types up to 95%–100%.

The World Health Organization has suggested that endotracheal aspirate or bronchoscopy with BAL be considered if a URT specimen is negative in patients with severe or progressive disease (World Health Organization, 2020). Based on a study involving 1,070 specimens from 205 patients with COVID-19, the positive detection rates using RT-PCR were 93% in BAL, 72% in sputum, 63% in nasal swabs, 32% in pharyngeal swabs and 29% in faecal samples (Wang et al., 2020). Although the sample size was inadequate, the results still inclined to a higher sensitivity in lower respiratory tract (LRT) than URT specimens. This patient had negative NPS/TS (4, 8 and 12 June) and negative DTS and stool on 9 June. There was radiological evidence of progression to LRT infection on 8 and 9 June, and thus the virus could only be detected from the LRT by bronchoscopy and BAL on 12 June. The negative URT specimens were likely related to the lower viral load and lower sensitivity of the tests, which had been performed by experienced nurses.

Apart from RT-PCR, serological tests may help to identify patients with COVID-19. However, it takes 6–7 days for detectable antibodies to develop. A study showed the median seroconversion time for antibodies, IgM and IgG as day 11, day 12 and day 14, respectively (Zhao et al., 2020). In the first week since symptom onset, a positive serological test is noted in fewer than 40% of patients only. Furthermore, the specificity of antibody detection tests varies. There is concern about false-positive results due to potential cross-reactivity with other coronaviruses. Thus, serological tests have limited utility for diagnosis in the acute setting.

According to the American Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology (AABIP) (Wahidi et al., 2020a), induced sputum collection is not recommended; whereas bronchoscopy is relatively contraindicated and should only be considered when less invasive testing to confirm COVID-19 is inconclusive or an alternative diagnosis that would impact clinical management is suspected. AABIP suggested to postpone bronchoscopy in suspected or patients with confirmed COVID-19 unless for emergent or urgent reasons, such as severe/moderate symptomatic tracheal/bronchial stenosis, symptomatic central airway obstruction, massive haemoptysis, migrated stent, foreign object aspiration and suspected pulmonary infection in immunocompromised patients (Verweij et al., 2020). In our case, bronchoscopy was performed to establish the diagnosis of COVID-19 and exclude other causes as the patient progressed to left upper and lower lobe pneumonia on 8 and 9 of June, while repeated SARS-CoV-2 testing on four URT specimens and a stool specimen was negative.

Performing bronchoscopy in suspected COVID-19 cases

Bronchoscopy is considered as an aerosol-generating procedure; therefore, it is recommended to implement airborne precaution (Interim Guidance for Public Health Personnel Evaluating Persons Under Investigation and Asymptomatic Close Contacts of Confirmed Cases at Their Home or Non-Home Residential Settings, 2020) although SARS-CoV-2 is usually transmitted by droplet, contact and fomites.

Minimising the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to healthcare workers (HCWs) is high in priority. Therefore, when bronchoscopy is indicated in patients with high suspicion of COVID-19, special precautions should be implemented. HCWs should use either N95 respirators or powered air-purifying respirators (PAPR) during bronchoscopy and in recovery rooms (Wahidi et al., 2020b). In addition, other PPE, including face shield, gown and gloves should be worn. Although no study with direct comparison of N95 and PAPR was identified, PAPRs have a theoretical benefit of higher filtration efficiency than N95. Moreover, PAPRs do not require prior fit testing, they also provide protection to the head thus additional face shield or cap are not needed. However, the training of proper doffing and decontamination procedures is required to minimise the risk of contamination.

Apart from proper PPE for HCWs, the logistics of bronchoscopy arrangement should be adjusted to minimise disease transmission. Instead of transferring the patient to the endoscopy centre, a mobile team of pulmonologists and endoscopy nurses can perform portable bronchoscopy inside the isolation ward. By doing so, the patient can remain in a negative pressure room all the time, thus minimising the exposure to others during transfer. Single-use bronchoscope may be considered, as there is no need for decontamination, and it carries lower risk of transmission of pathogens to other patients. A retrospective review in Singapore has demonstrated comparable microbiological yield in single-use and reusable conventional bronchoscope (70% vs 70%, P = 1.0) (Marshall et al., 2017). Another cost-analysis of single-use and reusable bronchoscopes in the intensive care unit (Perbet et al., 2017) showed that the cost per procedure for single-use scope was not higher than that for reusable scopes. Nevertheless, it depends on the frequency and number of procedures performed, maintenance costs and decontamination costs of reusable scopes.

In conclusion, it is important to maintain a high level of clinical suspicion in any patient with a strong epidemiological linkage of COVID-19. If multiple upper respiratory specimens and stool are negative for SARS-CoV-2, bronchoscopy is an essential investigation in the clinical management, while chest CT plays a supportive role in the diagnostic workup (Tavare et al., 2020). The implementation of infection control strategies are needed to minimise the risk of nosocomial transmission to HCWs and other patients during and after bronchoscopy.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not needed as there is no experimental intervention or treatment given to the patient.

Funding source

There is no funding source or sponsorship in this case report.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Hanson K., Caliendo A., Arias C., Englund J. 2020. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines on the diagnosis of COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Interim guidance for public health personnel evaluating persons under investigation (PUIs) and asymptomatic close contacts of confirmed cases at their home or non-home residential settings. Centers Dis Control Prev. [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.H., Junhao Lin R., Lin R.T.P., Barkham T., Rao P., Leo Y.S., et al. Testing for SARS-CoV-2: can we stop at 2? Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2246–2248. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui G., Ling L., Lai C.K., Tso E.Y., Fung K.S., Chan V., et al. Viral dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 across a spectrum of disease severity in COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81:318–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall D.C., Dagaonkar R.S., Yeow C., Peters A.T., Tan S.K., Tai D.Y.H., et al. Experience with the use of single-use disposable bronchoscope in the ICU in a tertiary referral center of Singapore. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2017;24 doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbet S., Blanquet M., Mourgues C., Delmas J., Bertran S., Longère B., et al. Cost analysis of single-use (Ambu® aScopeTM) and reusable bronchoscopes in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7 doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0228-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavare A.N., Braddy A., Brill S., Jarvis H., Sivaramakrishnan A., Barnett J., et al. Managing high clinical suspicion COVID-19 inpatients with negative RT-PCR: a pragmatic and limited role for thoracic CT. Thorax. 2020;75(7):537–538. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-214916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij P.E., Gangneux J.-P., Bassetti M., Brüggemann R.J.M., Cornely O.A., Koehler P., et al. Diagnosing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis. The Lancet Microbe. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/s2666-5247(20)30027-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahidi M.M., Lamb C., Murgu S., Musani A., Shojaee S., Sachdeva A., et al. American Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology (AABIP) statement on the use of bronchoscopy and respiratory specimen collection in patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2020;27:e52–4. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahidi M.M., Shojaee S., Lamb C.R., Ost D., Maldonado F., Eapen G., et al. The use of bronchoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chest. 2020;158(3):1268–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G., et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO - Interim guidance; 2020. Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Yuan Q., Wang H., Liu W., Liao X., Su Y., et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]