The epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread worldwide rapidly. This unique situation represents a significant challenge to our society and health-care system. Health-care workers (HCW) have to face intensive work and a high risk of infection while living in quarantine with less family support [1,2]. In this context, high rates of depression, anxiety, and insomnia have been reported in HCW [1,3,4]. Numerous studies focused on psychological symptoms of frontline HCW (i.e. HCW who are directly involved in the diagnosis, treatment, and care of patients with COVID-19) [1,2,4]. Although little attention has been paid to non-frontline HCW, a few studies found a higher risk of stress, anxiety, and insomnia for non-frontline HCW in comparison to fontline HCW [5,6].

Here we assessed the psychological impact of the epidemic on HCW during the first lockdown period in France (from 17 March to 11 May 2020). HCW from different wards of the University Medical Center of Lille (France) were invited to fullfill a self-administered questionnaire including socio-demographic characteristics and the Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety score (PHQ-4) [7]. Ethical approval was obtained via the Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté (CNIL) and the Local Data Protection Service (DEC20–155).

Two hundred and twenty-five HCW fulfilled the questionnaires. Among them, 45.7% were between 30 and 50 years old, 35.6% under 30, and 16.9% over 50; 84% were women; 43% were nurses, 8% were doctors, and 23% work night shifts. Based on previous conflicting results, we distinguished: (i) frontline HCW, (ii) non-frontline HCW who were impacted in their activity (i.e. “impacted/non-frontline HCW”) and (iii) non-frontline HCW whose activity was not impacted by the epidemic (i.e. “non-impacted/non-frontline HCW”). We performed a multivariate linear regression model explaining PHQ-4 score, according to the activity status (frontline HCW, impacted/non-frontline HCW, and non-impacted/non-frontline HCW) adjusted for age, gender, seniority, occupation, and work shift (day or night).

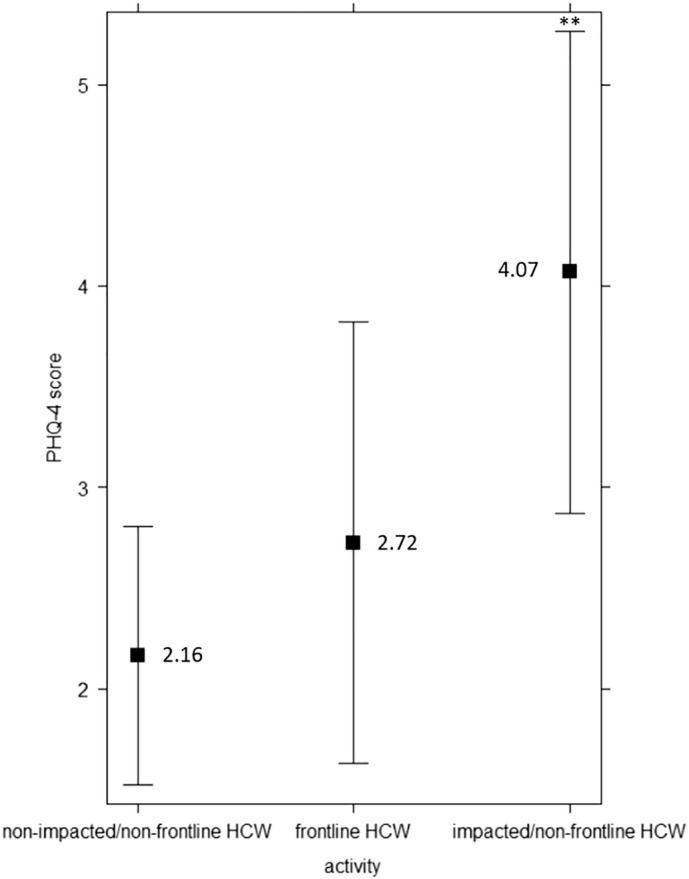

Interestingly, we found that impacted/non-frontline HCW had a higher score of depression and anxiety than both frontline HCW and non-impacted/non-frontline HCW (Fig. 1 ). This suggests that the most important stress factor for HCW is the confrontation to rapid and unplanned work reorganization, which mainly concerns non-frontline/impacted HCW who had to urgently replace their colleagues in different wards, or rapidly modify their activity depending on the pandemic situation and the situation in the frontline units, for example. This reorganization was stressful because of rapidly changing information, insufficient psychological support, and little training on personal protective equipment. Indeed, in the context of the covid-19 pandemic, many governments and hospitals have formulated a series of actions to support HCW, including supplementary external material, human resources, and psychological support, but these exceptional measures have been mainly deployed for frontline HCW [8].

Fig. 1.

Adjusted predicted PHQ-4 scores and CI95% according to the type of activity.

Results of the multivariate linear regression model explaining Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety score [7], ranging from 0 to 12, according to activity status (frontline HCW, impacted/non-frontline HCW, and non-impacted/non-frontline HCW) adjusted for age, gender, seniority, occupation and work shift (day or night).

Sample size: N = 160. (65 observations deleted due to missingness).

**: p-value <0,01 (compared to the reference: non-frontline HCW and non-impacted/non-frontline HCW).

Providing psychological support to HCW recently appeared as a significant public mental health challenge and the results presented in this study may have important practical implications. During the last months, a variety of critical incident stress debriefing or phone hotlines has been gradually implemented [1]. Our results show that support to HCW should not be restricted to frontline workers and should also involve non-frontline HCW whose professional activity was impacted by the pandemic. Moreover, previous studies pointed a better chance of achieving psychological interventions for HCW when psychologists are available within the units rather than when exceptional procedures (e.g., debriefing interventions) are initiated [9]. We thus believe that governments and hospitals should favor the regular presence of consultation-liaison psychologists in the different hospital departments, allowing for regular psychological and informal support.

The Covid-19 pandemic emphasizes the high levels of anxiety and stress of HCW. Beyond medical and psychological support to HCW during this unprecedented crisis, it is also critical to develop new healthcare management models for the next generations of doctors, nurses, and staff of health-care services.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the professionals of the consultation-liaison psychiatry service of the University Medical Center of Lille for their hard work with patients, but also with healthcare professionals, during this unprecedented sanitary crisis.

We would like to thank the Fondation de France, for the financial support to our consultation-liaison psychiatry service.

References

- 1.Cai Q., Feng H., Huang J., Wang M., Wang Q., Lu X., et al. The mental health of frontline and non-frontline medical workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: a case-control study. J Affect Disord. 2020 Oct 1;275:210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Que J., Shi L., Deng J., Liu J., Zhang L., Wu S., et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psychiatr. 2020 Jun 14;33(3) doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N., et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar 2;3(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y., Wang W., Sun Y., Qian W., Liu Z., Wang R., et al. The prevalence and risk factors of psychological disturbances of frontline medical staff in China under the COVID-19 epidemic: workload should be concerned. J Affect Disord. 2020 Dec 1;277:510–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan B.Y.Q., Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Jing M., Goh Y., Yeo L.L.L., et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Aug 18;173(4):317–320. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z., Ge J., Yang M., Feng J., Liu C., Yang C. Vicarious traumatization: a psychological problem that cannot be ignored during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;S0889-1591(20):30613–30619. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horn M., Granon B., Vaiva G., Fovet T., Amad A. Role and importance of consultation-liaison psychiatry during the Covid-19 epidemic. J Psychosom Res. 2020 Aug 5;137:110214. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galli F., Pozzi G., Ruggiero F., Mameli F., Cavicchioli M., Barbieri S., et al. A systematic review and provisional metanalysis on psychopathologic burden on health care workers of coronavirus outbreaks. Front Psych. 2020 Oct 16;11:568664. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.568664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]