Abstract

Background: Disparities in breastfeeding (BF) continue to be a public health challenge, as currently only 42% of infants in the world and 25.6% of infants in the United States are exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life. In 2019, the infants least likely to be exclusively breastfed at 6 months are African Americans (AA) (17.2%).

Materials and Methods: A scoping review of the literature was undertaken by using Arksey and O'Malley's six-stage framework to determine key themes of AA women's experience BF through an equity lens. Electronic databases of CINAHL and PubMed were searched for peer-reviewed, full-text articles written in the English language within the past 5 years by using the terms BF, AA, Black, sociological, cultural, equity, health, attitude, exposure, initiation, continuation, barriers, and facilitators.

Results: Initially, 497 articles were identified, and 26 peer-reviewed articles met the eligibility criteria. Through an equity lens, three main themes emerged, which summarized AA women's BF experience: cultural (family, peers and community support; misconceptions; personal factors), sociological (prejudices, racism, home environment; financial status; sexuality issues; BF role models; employment policies), and health dimensions (family involvement; timely and honest information from staff; baby-friendly hospital initiatives; postnatal follow-up; special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children).

Conclusion: For AA women, exclusively BF is beset with diverse cultural, health, and sociological challenges. Multifaceted approaches are needed for successful resolution of BF challenges to bridge the racial gap in BF in the United States. Future studies may explore interventions targeted to modifiable barriers to improve BF outcomes.

Keywords: African American, breastfeeding experience, equity

Introduction

Breastfeeding (BF) offers key preventative health benefits for women and their infants. To receive these optimal health benefits, exclusive breastfeeding must be maintained by women and their infants for the first 6 months of life.

The Healthy People 2030 (MICH-2030-15) initiative recognizes the health benefits of BF and has set a public health goal that 42.4% of infants in the United States be breastfed exclusively through 6 months.1,2 Although 42% of infants in the world meet the public health goal, only 25.6% of infants in the United States meet this target of being exclusively breast fed for the first 6 months of life.1,2 Even more concerning is that African American (AA) women in the United States,3 in particular, have the lowest BF initiation and continuation rates, with only 17.2% of infants exclusively breastfed at 6 months.4

The preventative health benefit of BF increases with longer BF duration. Women who report a cumulative BF history of 12 months or more decrease their risk for breast and ovarian cancers, diabetes, hypertension, and return to prepregnancy body shape.3,5,6 BF supports maternal well-being during the fourth trimester of pregnancy after birth by decreasing the risk of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, and it increases maternal self-efficacy.7

BF also provides lifelong infant health benefits; the longer infants exclusively breastfeed, the greater benefit in reducing infantile and respiratory diseases (COVID-19), sudden infant death syndrome, and chronic diseases related to obesity.8–12 Ultimately, the public health burden of not BF results in a global gross expenditure of U.S. $341.3 billion, with $114.97 billion incurred by the North America Region.13 The early cessation of BF (before 3 weeks) costs the United States an estimated $3.0 billion annually (2010 dollars) due to purchase of formula, increased infantile diseases and health visits, and lost wages ($2.3 billion being maternal costs).13

Many AA women encounter unique challenges in initiating and sustaining BF. Notably, inadequate social support,4,12,14,15 various forms of prejudices,16 racism,17 misconceptions about BF versus formula feeding,18 insufficient financial resources,16,19,20 as well as personal factors such as low self-efficacy, negative attitudes, unwillingness to breastfeed, misconceptions about the benefits,21,22 and inadequate resources.23

Support is a critical factor in addressing these challenges to meet and sustain BF practice.4,15,24 AA women who obtain some forms of support from relatives, health staff, and employers are more motivated to breastfeed.15,25 In addition, participating in programs such as Centering during Pregnancy, Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), and the “Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children Services,” also known as the WIC Program, encourages BF initiation and duration. The aforementioned types of support contribute to women's BF self-esteem and it has been found that women with high self-esteem breastfed more frequently and for longer duration.26–28

The purpose of the scoping review was to explore the BF experiences of AA women, with critical attention to the cultural, sociological, and health dimensions through an equity lens to positively impact BF initiation and continuation in the United States.

Materials and Methods

The scoping review was done based on the seminal scoping review method as outlined by Arksey and O'Malley.29 In the first stage, the research question to be addressed was identified as, “What is the experience of AA women in the United States?” In the second stage, articles were selected based on relevance to the topic from the databases of PubMed and CINHAL. The search terms adopted for the review were: BF, AA, Black, sociological, cultural, equity, health, attitude, exposure, initiation, continuation, barriers, and facilitators.

The third stage involved the selection of data. This was limited to full-text articles written in the English language from peer-reviewed journals, all research types (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods), and published within the past 5 years. Stage four concentrated on charting the data based on iterative process whereas stage five focused on collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. Lastly, for validation, a lactation consultant was asked to validate the scoping review analysis.

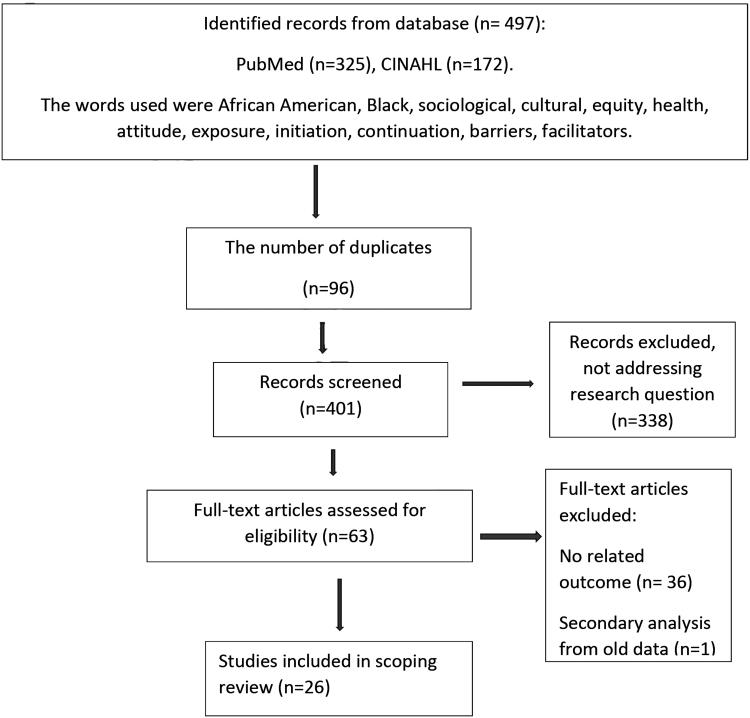

The initial search of the electronic database resulted in the identification of 497 articles—with 96 duplicates, and 338 not addressing the research question. Subsequently, 63 full text-articles remained eligible for screening, 36 were excluded for unrelated outcomes, and 1 article was excluded that was a secondary analysis of historical data. Thus, 26 full-text articles remained for the scoping review analysis (Fig. 1). “Arksey and O'Malley framework” was used to conduct a quality assessment of the studies (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Flowchart of the article selection process for the scoping review.

Table 1.

Scoping Review on Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation Support Among African Americans

| Author, year, study site | Method | Sample | Trustworthiness | Findings | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson et al., 2019, Southeast Wisconsin | Qualitative Two focus group discussions |

9 AA women, ≥18 years currently BF or breastfed 6 months before the study. | Verbatim transcription, member checking, audit trail and expert support. | The role of BF peer counselors had a positive impact on lactation. Four themes: Educating with truth, validating for confidence, countering others negativity, supporting with solutions. | Establishment of standard guidelines for BF peer counselor's intervention. |

| Hinson et al., 2018, Northeastern US | Qualitative Six focus group discussions |

United States born—AA woman, ≥18 years, within 3 months postpartum. | Prolong engagement, transcription, field notes, member checking. | BF initiative among AA is affected by: cultural beliefs, (benefits, bonding, natural, “wet nurse” history, formula is as good as breast milk, racism); sexuality issues (breasts for nutrition, over-sexualization of AA females, sexual act); social environment (familial/network influence—self, mother, sisters, partner, friends/peers, religious community); information sources (prenatal clinics, WIC, physicians, nurses, lactation consultants, internet), BF intentions (positive, negative or ambivalent), barriers (pain, embarrassment of public exposure, lack of knowledge and support of BF in AA community, lack of information and education about BF, prenatally lack of access to equipment and resources, aversions to BF, convenience of bottle and FF independence, national policy), and facilitators (involved fathers, prior positive experience, cost and convenience of BF, peer counselors/peer support groups, supportive family environment, BFHI, WIC). | Multifactorial approach, involving mothers, partners, and community to address cultural barriers to lactation. |

| Schindler-Ruwisch et al., 2019, Washington, DC | Qualitative 24 Interviews |

24 AA women aged ≥18 years, in WIC with infants 0–8 months. | Prolong engagement, transcription, dual coding, Kappa 0.7107. | Four themes of BF initiation: Influence of others on BF confidence and intention; benefits; pervasiveness of obstacles (pain, latch, milk supply); and importance of social support (emotional, instrumental, appraisal, informational, provider support WIC). | Reinforcement of community outreach program through social support geared toward BF. |

| Furman et al., 2016, Cleveland | Quantitative Pre- and post-test |

66 Partners/partners, predominantly self-identified AA, aged 17–64 years. | No validity or reliability tests done. | Improved knowledge in lactation (62%) and readiness to welcome BF of next infant (85%). | Engagement of inner city and AA fathers or partners as priority in BF initiatives. |

| Oniwon et al., 2016, Washington, DC | Quantitative Cross-sectional |

100 multiparous women in WIC, predominantly AA, aged 18–41 years. | No validity or reliability tests stated. | Women (71%) initiated BF based on education level, full-time or no job status, had one child, and was breastfed in childhood. Barriers for BF continuation at home—limited support, pain, insufficient milk perception. | Improvement in prenatal education, and reinforcement of BF exclusivity in though outpatient services. |

| Barbosa et al., 2017, Richmond, VA | Qualitative Seven focus group discussions |

25 low-income AA women, aged ≥18 years, enrolled in WIC, with a child <2 years. | Transcription, member checking. | Positive deviance factors—BF intention, high self-efficacy and sought knowledge, value BF and understood FF disadvantage, varied interpersonal support, resist negative BF/positive FF influences, positive BF influence on others, prenatal health providers promote BF and FF products, hospital offered good BF instruction and support, postnatal staff gave limited support/advise, appreciate WIC BF help, overcame job barriers, indifferent to BF stigma and public BF. | Community engagement to promote strengths of positive deviance toward BF. |

| Asiodu et al., 2017, Northern California | Qualitative Ethnographic |

22 AA (14 pregnant women and eight support people). | Prolong engagement triangulation |

Themes related to BF decision making—best for baby; normalization/role models; social support; fluid social dynamics, resiliency; seeking support and empowerment; stress, shame, and guilt; combination feeding. | Education through identified social support person, social media platform, and combination feeding. |

| Thomson et al., 2017, Mississippi | Quantitative Experimental |

82 AA | Randomization No blinding High attrition rate. |

BF knowledge increased in both groups, 39% participants BF infant for ≥6 months. Pre-pregnancy weight and BF intent were significant for BF initiation. | Using peer counselors with BF experience and inclusion of male partners in education. |

| Robinson et al., 2018 | Quantitative Systematic review and meta-analysis |

Four identified | PRISMA guidelines | AA pregnant women who participated in Centering Pregnancy Models had a 71% probability of BF observed. | Outcomes of Centering Pregnancy model for AA women |

| Merewood et al., 2019, Southern US | Quantitative Longitudinal (2014–2017) |

Hospitals enrolled in Communities and Hospitals Advancing Maternity Practices | Validity and reliability tests not stated. No blinding |

BF initiation and exclusivity among AA infants increased from 46% to 63% (p < 0.05) and from 19% to 31% (p < 0.05), respectively. | None stated. |

| Kim et al., 2017, Illinois | Mixed method Interviews and questionnaire |

15 first-time AA mothers enrolled in WIC. | Validated instrument used (IIFAS and BFSE-SF) data saturation reached, transcription, member checking. | BF facilitators and barriers—Themes: Normative infant behavior in sociocultural context; cultural beliefs on maternal nutrition and BF; time and cost associated with BF; managing and integrating BF while maintaining a social life; necessity of social support from significant others and female role models; suboptimal support from institutions (hospitals, school, work place and community). Positive attitude to BF (70%) and high self-efficacy (62%). | Interventions focusing on social support (emotional, tangible, informational, and encouragement). |

| Robinson et al., 2019, Internet | Qualitative Four focus group discussions |

22 AA women, aged ≥18 years, participating in BF support groups on Facebook. | Transcription, peer debriefing, member checking, expert input, triangulation. | Themes: Creating a community for Black mothers; online interactions and level of engagement; empowerment of self and others; shifts in BF perceptions and beliefs. | None stated |

| Robinson et al., 2019, Online | Quantitative Online cross-sectional survey |

277 AA women | Validated instruments used (IIFAS and BFSE-SF) | Average BF intention duration was 19 months, due to Facebook support. Self-efficacy and BF attitudes remained significant predictors of intended BF duration. | Impact of Facebook support on prolonged BF durations in AA women. |

| Spencer et al., 2015 | Qualitative Sequential-Consensual Qualitative Design |

Stage 1: Four AA key informants Stage 2: 17 AA mothers BF infant for ≥4weeks Stage 3: 7 AA women |

Prolonged engagement, transcription, peer debriefing | Stage 2 themes: Self-determination; spirituality and BF; and empowerment Stage 3 themes: Engaging spheres of influence; sparking BF; activism; and addressing images of the sexual breast versus the nurturing breast. |

Engaging supportive network; pediatricians' and obstetricians' view on BF attitude and knowledge; culturally sensitive educational interventions and initiatives (mother's time, activities). |

| Obeng et al., 2015, Midwest | Qualitative Focus group discussion |

20 AA women, aged 20–40 years | Prolonged engagement, verbatim transcription | Themes identified on AA women BF perceptions and experiences: Health benefits, lack of information, negative perceptions of BF by others, organizational support, unforeseen circumstances of BF. | Explore ways to increase BF initiation and duration among AA women based on their experiences, desires, and needs. |

| Johnson et al., 2016, Detroit | Qualitative Focus group discussion |

38 Pregnant and lactating AA women and racial diverse health professionals | Transcription, | Health workers not always supportive of BF, lacked adequate information and skill to educate AA women on BF, so women lost confidence in them and relied more on relatives and peers. | None stated |

| Jefferson, 2017 | Quantitative Cross-sectional survey |

696 AA and Caucasian college students, aged ≤45 | Validated instrument used, IIFAS | Favorable attitude to BF but FF was viewed as much easier; odds of experiencing BF exposure and positive BF attitudes were thrice higher for Caucasian students than for AA students. | Further studies to identify strategies to improve BF exposure and attitudes among AA students. |

| DeVane-Johnson et al., 2017, Online | Qualitative Integrative literature review |

Four social science electronic databases, 47 peer-reviewed articles. | Theme validation by two independent authors | Themes for BF disparities among AA women: Social characteristics (e.g., low socioeconomic status, single); perceptions of BF; quality of BF information provided by health care providers. |

Focus on sociohistorical factors that have shaped current norms of BF among AA women. |

| Kamoun and Spatz, 2018, West Philadelphia | Mixed methods Interview Survey |

Interview: 10 leaders, 44 members and 11 leaders surveyed, ≤45-year, AA, Muslim, both sexes. | Validated instrument used, IIFAS; verbatim transcription, member checking. | No prevalence of Islamic education on BF; favorable views about BF, attitude toward BF improved through religious incorporation on BF education. | None stated |

| Moon et al., 2017 | Quantitative Randomized controlled trial |

1,194 AA women who had just delivered, aged 18–42 years. | Random selection and assignment | BF was 5.3 and 6.1 weeks for infants who room or bed-shared (p = 0.01). Exclusive BF was 3.0 and 1.6 weeks for infants bed-shared or room shared (p < 0.001). Group assignment did not affect BF duration. AA infants <6 months were mostly room shared. | Further research on factors that improve BF exclusivity and duration. |

| Lutenbacher et al., 2016 | Qualitative Focused group discussion |

16 Self-identified AA women with one birth history within 5 years. | Prolonged engagement, verbatim transcription, field notes, peer debriefing. | Factors affect BF: four themes—Balancing the influences of people, myths, and technology; being in the know; critical periods; and, supportive transitions. | None stated |

| Fabiyi et al., 2016, Central Ohio | Qualitative Interviews |

20 Middle-class AA and African-born women | Verbatim transcript, prolonged engagement, member checking | Factors affecting BF: Persistent support and encouragement; dissuasive remarks; challenges with health, job, lactation, ambivalent BF attitude. | None stated |

| Deubel et al., 2019, Florida | Qualitative Interviews |

20 AA women | Prolonged engagement, verbatim transcription. | BF challenges—No maternity leave, access to electric pumps, BF role models and or support network to normalize long-term BF, social pressures to initiate formula supplementation, fears that BF renders infants overly dependent on mother's care. | Monitoring the practical implementation of insurance coverage for BF pumps on rates of BF initiation and duration. |

| LoVerde et., 2018 | Qualitative Interviews |

Nine AA women with VLBW (≤1,500 g) | Prolonged engagement, point of saturation, member checking, verbatim transcription | Facilitators to BF: Being a mother; neonatal intensive care unit environment; community support; useful resources. Barriers: Maternal illness; milk expression; challenging home environment; emotional distress. |

Perceived barriers to improve provision of mother's own milk and quality of lactation journey of AA women with preterm infants. |

| Robinson et al., 2019 | Mixed methods Scoping review |

MEDLINE articles (5) using PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, and Sociological abstracts | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. |

AA women experience racism, bias, and discrimination affecting BF care, support, and outcomes. | Effect of racism, bias, and discrimination on BF care, support, and outcomes. |

| Griswold et al., 2019 | Quantitative Secondary data analysis of Black Women's Health Study (1995–2005) |

2,705 for BF initiation analysis, 2,172 for BF duration analysis. | Validity and reliability tests not stated. | Racism in work environments was associated with lower odds of BF duration at 3–5 months; whereas higher odds of BF initiation duration at 3–5 and 6 months were observed in study participants who had experienced racism with the police; U.S.-born AA or having one parent born in the U.S. predicted lower odds of BF initiation and duration; residence in segregated neighborhood (mainly Black residents) during childhood decreased BF initiation and duration as compared with living in predominantly White communities of residence. | Influence of different racism experiences on BF behaviors for Black women in the United States and innovative interventions. |

Scoping Review Chart on Quality Assessment of Studies as Guided by the “Arksey and O'Malley Framework.”

AA, African American; BF, Breastfeeding; BFHI, Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative; BFSE-SF, Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Short Form; FF, formula feeding; IIFAS, Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale; VLBW, very low birth-weight infants; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children.

Results

Initially, 497 articles were identified, and 26 peer-reviewed articles met the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Table 1 provides the complete overview of findings from each of the reviewed articles. Through an equity lens, three general themes emerged to describe the BF experiences of AA women in the United States, namely, cultural, sociological, and health dimensions. The definitions of the themes cover three dimensions and include: (1) Cultural, which includes the personal and familial network values influencing or inhibiting women to breastfed; (2) Sociological, which includes the larger community perception of BF, sexualization of the breast, and the societal issues of prejudice and racism toward AA women BF; and (3) Health, the interface between women and their health care providers, and health care system to support BF.

Theme one: Cultural dimension

Culture defined the BF decisions of AA women in the United States.16,22,30 The family, peers, and community were important agents for social support. Families, peers, and community persistent support and encouragement for women boosted BF.19,31–33 The communal networks were instrumental for education, counseling, appraisal, interaction, engagement, successful transitions, positive deviance, reinforcement, and emotional well-being.26,34,35 The AA women who breastfeed exhibit positive deviance. Positive deviance refers to the fact that such women chose to breastfeed their infants contrary to the cultural norms of not breastfeeding post-slavery. Such influences became possible through in-person interactions, virtual platforms, and religious affiliations.30,33,36

Various forms of misconceptions on BF were observed within the AA community. For instance, some relatives, peers, and close neighbors claimed that breastfed infants become overly dependent on their mother; such myths pressurized women to initiate formula supplementation.23 Formula supplementation was seen as inexpensive, required less time, and allowed women to manage and maintain their social life.20,37 Conversely, social media engagement brought shifts in maternal BF beliefs and perceptions,38 which resulted in increased willingness to breastfeed beyond the infant's first year.36

Personal factors influenced the BF experiences of women. Maternal self-determination, positive attitude, positive deviance, high self-efficacy, spirituality, and empowerment20,32 motivated women to breastfeed. On the contrary, women who experienced stress, shame, guilt,34 embarrassment of public exposure,16 prejudiced public perceptions, challenges with milk expression,21,22 BF pain, and previous limited BF success39 were more likely to not breastfeed compared with the other women.26

Theme two: Sociological dimension

Issues of prejudice and racism may have an influence on AA women's BF practices.32,39 Health professionals, for example, pediatricians and obstetricians, negatively posited that AA women are less likely to breastfeed their infants and had less BF knowledge.17,32,39 Prejudice in BF is grounded in historical antecedents, where AA women were mandatory “wet nurses”16 to the slave masters' children instead of BF their own infants and current racial challenges.18

For instance, racism in the workplace was associated with lower odds of BF duration at 3–5 months; whereas higher odds of BF duration at 3–6 months were observed in study participants who had experienced racism with the police. In addition, lower odds of BF initiation were reported in U.S.-born AA women or a woman with a U.S.-born parent and residents of mainly Black communities as compared with women who lived in predominantly White communities in childhood.18

Household composition and living arrangement are critical components of the social life of AAs.16 AA women mostly lived in multigenerational households or as single parents.16,40 The home environment affected maternal BF decisions and support postpartum.25 For instance, women who lived in resource-limited communities experienced major financial challenges.16,20,40 Therefore, the limited income constrained maternal access to the procurement of electric BF pumps and additional BF resources.16 Such experiences influenced the perceptions of some of the women to view BF as expensive.16

Working AA women, in particular, indicated a persistent need for organizational support toward BF.19,39 Support recommendations included paid maternity leave, absence of dissuasive remarks, encouragement toward maternal BF efforts, access to electric pumps, and insurance coverage for BF pumps.19,23 Women were optimistic that addressing these factors will overcome stigma around public BF.26 Moreover, the need to promote national policies favorable to BF at the workplace was recommended.16

The over-sexualization of AA women's breast was an issue, specifically emphasis of the breast for sexual acts rather than nutrition.16 Thus, suggestions were made to engage all spheres of influence to address images of the sexual breast versus the nurturing breast.32 In addition, BF role models were noted to be important in the BF experience of AAs.20,23,41 Such role models focused on emotional, tangible, informational, and encouragement interventions for women. Older sisters and grandmothers were recognized as the best suited for such roles.20,23,41

Theme three: Health dimension

The health dimension theme encompassed the importance and value of a supportive health care system and supportive health care professionals toward the success of women's BF experiences. For instance, timely and honest information from staff, WIC, BFHI, postnatal support, and follow-up was identified.16,19,21,22,32,39,40,42 Such information was meant to promote persistent support and encouragement, which included training on milk expression.21,26 The quality of BF information provided by health care providers was important.40 Thus, culturally sensitive educational interventions and initiatives responsive to women's time and activities were stressed.32

When health care workers failed to include such interventions, staff were deemed not supportive and lacked adequate information and skill to educate AA women on BF. As a result, women lost confidence and relied more on relatives and peers.42 In addition, women preferred a system and professional approach to be inclusive of the partners in BF decisions.25

Another health care system mentioned by women was the role of peer counselors and there was an indication of a positive impact on lactation.38 Women viewed peer counselors' educational efforts as truthful, confidential, supportive, and helped dispel misconceptions about BF. Although effective, there remains a need to establish standard guidelines for peer counselors' BF interventions.38 An exemplar of the integration of the community, health care system, and BF is the Communities and Hospitals Advancing Maternity Practices Program.28 AA women received community-based perinatal BF support, which contributed to increased BF initiation (46–63% [p < 0.05]) and exclusivity (19–31% [p < 0.05])28 rates.

Discussion

This scoping review provides valuable insight into the BF experiences of AA women in the United States. Through an equity lens, three main themes were identified that influenced the BF experiences of AA women in the United States, namely, the cultural, sociological, and health dimensions.

Similar to earlier findings, the cultural experiences of racism, positive deviance, personal factors such as self-esteem, maternal attitude, and BF misconceptions16–18 contribute to AA women's BF outcomes. These findings suggest that AA women need support with the mitigation of existing misconceptions and racial challenges to bridge the gap in BF. Such efforts may be achieved through the strengthening available via social support efforts by the familial associations, social networks.19,31–33,36

In addition, active inclusion of religious bodies as primary partners in BF promotion with the AA population should be included as part of cultural and sociological targeted interventions.19,31–33,36 Exemplars for these community-, state-, and tribal-level interventions targeting BF promotion for all women of diversity are supported by the national coalition of organizations, the United States Breastfeeding Committee (USBC). The USBC is committed to mitigating barriers by addressing the essential components of culturally competent BF care: consider Culture, show Respect, Assess/Affirm differences, show Sensitivity and Self-awareness, and do it all with Humility (CRASH).43

AA women's need for socioeconomic support was confirmed in this review.16,19,20 A significant social barrier in AA women's BF is the lack of BF role models across generations.23,41 An additional barrier is the perceived social value of the female breast as a sexual organ and not a source of nutrition.16 Targeted messaging is needed to promote the nutritional value and less emphasis on the over-sexualization of the AA female breast. Together, the change in messaging will support women to feel more comfortable to breastfeed with less stigma and better self and public acceptance.

Lastly, as observed in previous studies, women called for health care systems and health care providers to support their BF efforts.15,25 In this scoping review, women emphasized the need for persistent, truthful, family-inclusive, culturally sensitive support from the first to the fourth trimester.28,32,42 Thus, health professionals who actively engage with AA women throughout the four trimesters of pregnancy must proactively promote BF initiation and continuation. Further, BF support needs to integrate perinatal programs beginning in the community and continuing to the hospital setting and then back into the community so women and infants can receive the benefits of BF.

Conclusions

AA women's BF experiences are confronted with diverse and unique challenges. These challenges require the collaborative efforts on the part of the individual woman, her family and peers, her community (religious institutions and employers), the health care system and its providers, as well as national policies for successful mitigation. The results of such efforts will address the current gap in BF initiation and continuation of BF for AA women and infants in the United States. Future studies should explore social support, including the role of the religious community, and its influence on AA's BF outcomes.

Authors' Contributions

The authors contributed equally to the writing of this article.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding facts. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/facts.html (accessed December13, 2020)

- 2. UNICEF. Infant and young feeding. 2019. https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/infant-and-young-child-feeding (accessed December13, 2020)

- 3. Ganju A, Suresh A, Stephens J, et al. Learning, life, and lactation: Knowledge of breastfeeding's impact on breast cancer risk reduction and its influence on breastfeeding practices. Breastfeed Med 2018;13:651–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beauregard JL, Hamner HC, Chen J, et al. Racial disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration among U.S. Infants Born in 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:745–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schalla SC, Witcomb GL, Haycraft E. Body shape and weight loss as motivators for breastfeeding initiation and continuation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ross-Cowdery M, Lewis CA, Papic M, et al. Counseling about the maternal health benefits of breastfeeding and mothers' intentions to breastfeed. Matern Child Health J 2017;21:234–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stuebe AM, Grewen K, Meltzer-Brody S. Association between maternal mood and oxytocin response to breastfeeding. J Womens Health 2013;22:352–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics 2004;114:297–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berger PK, Lavner JA, Smith JJ, et al. Differences in early risk factors for obesity between African American formula-fed infants and White breastfed controls. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2017;3:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boateng GO, Martin SL, Tuthill EL, et al. Adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale to assess exclusive breastfeeding. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;7:1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mulder PJ A concept analysis of effective breastfeeding. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2006;35:332–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spencer BS, Grassley JS. African American women and breastfeeding: An Integrative Literature Review. Health Care Women Int 2013;34:607–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walters DD, Phan LTH, Mathisen R. The cost of not breastfeeding: Global results from a new tool. Health Policy Plan 2019;34:407–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balogun OO, Ej OS, Mcfadden A, et al. Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding (Review) Summary of findings for the main comparison. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oniwon O, Tender JAF, He J, et al. Reasons for infant feeding decisions in low-income families in Washington, DC. J Hum Lact 2016;32:704–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hinson TD, Skinner AC, Lich KH, et al. Factors that influence breastfeeding initiation among African American Women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2018;47:290–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robinson K, Fial A, Hanson L. Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health 2019;64:734–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Griswold MK, Crawford SL, Perry DJ, et al. Experiences of racism and breastfeeding initiation and duration among first-time mothers of the Black Women's Health Study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2018;5:1180–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fabiyi C, Peacock N, Hebert-Beirne J, et al. A qualitative study to understand nativity differences in breastfeeding behaviors among middle-class African American and African-Born Women. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:2100–2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim JH, Fiese BH, Donovan SM. Breastfeeding is natural but not the cultural norm: A mixed-methods study of first-time breastfeeding, African American mothers participating in WIC. J Nutr Educ Behav 2017;49:S151–S161.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. LoVerde B, Falck A, Donohue P, et al. Supports and barriers to the provision of human milk by mothers of African American preterm infants. Adv Neonatal Care 2018;18:179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schindler-Ruwisch J, Roess A, Robert RC, et al. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation and duration among African American DC WIC recipients: Perspectives of recent mothers. Womens Health Issues 2019;29:513–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deubel TF, Miller EM, Hernandez I, et al. Perceptions and practices of infant feeding among African American women. Ecol Food Nutr 2019;58:301–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Balogun OO, O'Sullivan EJ, McFadden A, et al. Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;11:CD001688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Furman L, Killpack S, Matthews L, et al. Engaging inner-city fathers in breastfeeding support. Breastfeed Med 2016;11:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barbosa CE, Masho SW, Carlyle KE, et al. Factors distinguishing positive deviance among low-income African American Women: A qualitative study on infant feeding. J Hum Lact 2017;33:368–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevetion. Facts national breastfeeding goals. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/facts.html#goals (accessed December13, 2020)

- 28. Merewood A, Bugg K, Burnham L, et al. Addressing racial inequities in breastfeeding in the southern United States. Pediatrics 2019;143:e20181897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kamoun C, Spatz D. Influence of Islamic traditions on breastfeeding beliefs and practices among African American Muslims in West Philadelphia: A mixed-methods study. J Hum Lact 2018;34:164–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lutenbacher M, Karp SM, Moore ER. Reflections of Black women who choose to breastfeed: Influences, challenges and supports. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Spencer B, Wambach K, Domain EW. African American women's breastfeeding experiences: Cultural, personal, and political voices. Qual Health Res 2015;25:974–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomson JL, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Goodman MH, et al. Low rate of initiation and short duration of breastfeeding in a maternal and infant home visiting project targeting rural, Southern, African American women. Int Breastfeed J 2017;12:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Riley B, Schoeny M, Rogers L, et al. Barriers to human milk feeding at discharge of very low-birthweight infants: Evaluation of neighborhood structural factors. Breastfeed Med 2016;11:335–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Robinson K, Vandevusse L, Foster J. Reactions of low-income African American women to breastfeeding peer counselors. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2016;45:62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robinson A, Lauckner C, Davis M, et al. Facebook support for breastfeeding mothers: A comparison to offline support and associations with breastfeeding outcomes. Digit Health 2019;5:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jefferson UT Breastfeeding exposure, attitudes, and intentions of African American and Caucasian college students. J Hum Lact 2017;33:149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Robinson A, Davis M, Hall J, et al. It takes an e-village: Supporting African American mothers in sustaining breastfeeding through Facebook communities. J Hum Lact 2019;35:569–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Obeng CS, Emetu RE, Curtis TJ. African-American women's perceptions and experiences about breastfeeding. Front Public Health 2015;3:273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. DeVane-Johnson S, Woods-Giscombé C, Thoyre S, et al. Integrative literature review of factors related to breastfeeding in African American women: Evidence for a potential paradigm shift. J Hum Lact 2017;33:435–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fleurant E, Schoeny M, Hoban R, et al. Barriers to human milk feeding at discharge of very-low-birth-weight infants: Maternal goal setting as a key social factor. Breastfeed Med 2017;12:20–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Johnson AM, Kirk R, Rooks AJ, et al. Enhancing breastfeeding through healthcare support: Results from a Focus Group Study of African American Mothers. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:92–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. United States Breastfeeding Committee Diversity, equity and inclusion. www.usbreastfeeding.org/p/cm/ld/fid=199 (accessed December13, 2020)

- 44. Asiodu IV, Waters CM, Dailey DE, et al. Infant feeding decision-making and the influences of social support persons among first-time African American mothers. Matern Child Health J 2017;29:864–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Robinson K, Garnier-Villarreal M, Hanson L. Effectiveness of Centering Pregnancy on breastfeeding initiation among African Americans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinat Neonat Nurs 2018;32:116–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moon RY, Mathews A, Joyner BL, et al. Impact of arandomized controlled trial to reduce bedsharingon breastfeeding rates and duration for African-American infants. J Community Health 2017;32:707–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Griswold MK, Crawford SI, Perry DJ, et al. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2018;5:1180–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]