Abstract

BACKGROUND

Variability of aldosterone concentrations has been described in patients with primary aldosteronism.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective cohort study of 340 patients with primary aldosteronism who underwent adrenal venous sampling (AVS) at a tertiary referral center, 116 of whom also had a peripheral venous aldosterone measured hours before the procedure. AVS was performed by the same interventional radiologist using bilateral, simultaneous sampling, under unstimulated and then stimulated conditions, and each sample was obtained in triplicate. Main outcome measures were: (i) change in day of AVS venous aldosterone from pre-AVS to intra-AVS and (ii) variability of triplicate adrenal venous aldosterone concentrations during AVS.

RESULTS

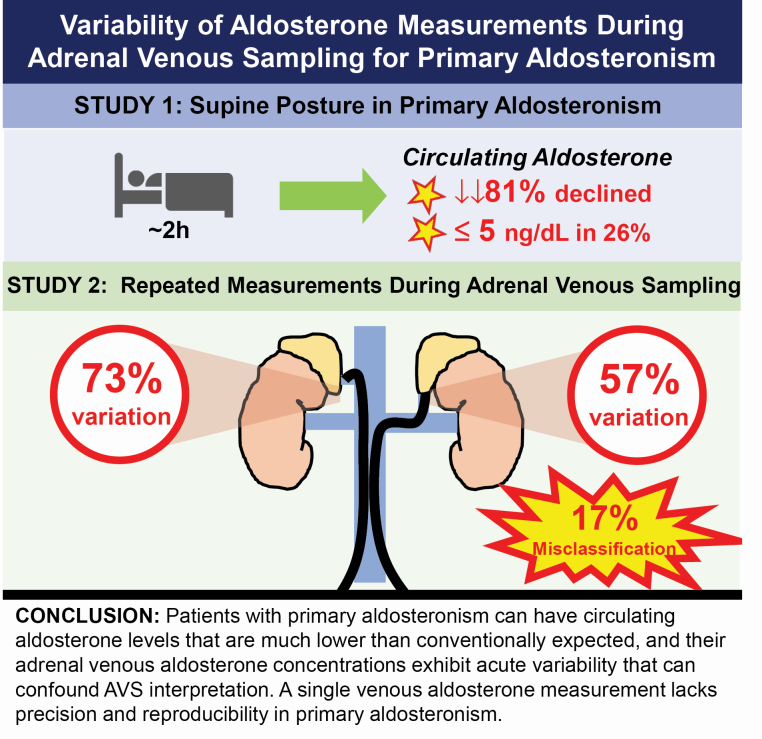

Within an average duration of 131 minutes, 81% of patients had a decline in circulating aldosterone concentrations (relative decrease of 51% and median decrease of 7.0 ng/dl). More than a quarter (26%) of all patients had an inferior vena cava aldosterone of ≤5 ng/dl at AVS initiation. The mean coefficient of variation of triplicate adrenal aldosterone concentrations was 30% and 39%, in the left and right veins, respectively (corresponding to a percentage difference of 57% and 73%), resulting in lateralization discordance in up to 17% of patients if the lateralization index were calculated using only one unstimulated aldosterone-to-cortisol ratio rather than the average of triplicate measures.

CONCLUSIONS

Circulating aldosterone levels can reach nadirs conventionally considered incompatible with the primary aldosteronism diagnosis, and adrenal venous aldosterone concentrations exhibit acute variability that can confound AVS interpretation. A single venous aldosterone measurement lacks precision and reproducibility in primary aldosteronism.

Keywords: adrenal venous sampling, aldosterone, blood pressure, hypertension, primary aldosteronism

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Primary aldosteronism is a frequent cause of secondary hypertension.1–5 Studies have shown, however, that aldosterone levels can be highly variable in primary aldosteronism. Healthy volunteers exhibit a diurnal pattern of aldosterone production and a superimposed burst-like pulsatility throughout the day.6 Similarly, patients with primary aldosteronism also exhibit circadian variation and pulsatility of aldosterone, such that circulating aldosterone levels may vary as much as 4-fold above or below the daily mean value.7 One of the important clinical implications of this variability in aldosterone is that a single measure of circulating aldosterone may be insensitive. A substantial proportion of patients with confirmed primary aldosteronism can, at times, have peripheral venous aldosterone concentrations that fall well below the conventional thresholds of screening, potentially leading to a missed clinical diagnosis if only a single venous aldosterone level is relied upon.8 For example, nearly a quarter of resistant hypertension patients with confirmed primary aldosteronism can exhibit a circulating aldosterone level less than 10 ng/dl.9,10

Recently, Kline et al. compared aldosterone levels at the time of primary aldosteronism diagnosis with levels from the inferior vena cava at the initiation of adrenal venous sampling (AVS). Remarkably, they observed that 72% of patients had aldosterone levels at AVS that were more than 30% lower than at diagnosis, and in 13% of instances lower than 5 ng/dl, a threshold conventionally considered to be incompatible with primary aldosteronism.11

Collectively, these findings suggest that the conventional concept of primary aldosteronism manifesting with persistently “high” and nonsuppressible aldosterone levels may need to be revised and that multiple independent measurements of aldosterone may be needed to avoid missing the diagnosis. Although international guidelines suggest that multiple aldosterone and renin measurements should be obtained if initial testing is inconclusive, or nondiagnostic, despite a high pretest probability, obtaining more than 1 a priori sample for diagnostic testing is not explicitly recommended or routinely performed.12 Similarly, although several expert AVS centers obtain multiple adrenal venous samples, protocols vary considerably from site-to-site, and most AVS procedures do not incorporate repeated measurements.

To further investigate the range and scope of aldosterone variability, we performed a retrospective analysis of patients with biochemically confirmed primary aldosteronism who underwent AVS to assess:

1) the acute variability in circulating venous aldosterone levels measured within an interval of a few hours; and

2) the acute variability of adrenal aldosterone concentrations obtained from repeated (triplicate) adrenal vein measurements during AVS.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This was a retrospective study including patients with primary aldosteronism who were referred for AVS at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Harvard Medical School, between 2005 and 2019. All patients had confirmed primary aldosteronism based on criteria recommended by the Endocrine Society12; either a dynamic confirmatory test and/or a very high aldosterone (≥20 ng/dl) in the context of a suppressed renin, hypertension, and hypokalemia. Participants were eligible for this study if they had a successful AVS procedure with adequate selectivity of each adrenal vein, defined as a stimulated selectivity index (SI) of ≥3 (the mean adrenal vein cortisol divided by the inferior vena cava (IVC) cortisol following a bolus of 250 mcg of cosyntropin). The percentage of patients at our institution who have a successful (i.e., selective) AVS procedure is approximately 95% and the same interventional radiologist and staff conducted all AVS procedures; a total of 340 patients met these criteria and were included in the analyses. Although a stimulated SI cutoff of ≥3 is supported by expert guidelines,13 we recognize that other centers may use different definitions of selectivity; therefore, we also analyzed results using other SI thresholds to determine whether such differing analyses would change the study results.

Patients were given potassium supplements, if needed, prior to the AVS to normalize potassium and none of the patients undergoing AVS were on a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist for at least 4 weeks prior to the procedure. All study participants gave informed consent and all study procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines (protocol 2013P000564).

AVS protocol

On the day of AVS, patients reported to the radiology care unit in the morning (0800–1200), 2–3 hours prior to the procedure, and were placed in a supine position. Per the standard clinical protocol at our institution, this supine posture was maintained throughout the day until discharge to home. An intravenous catheter was inserted into the arm of each patient; in 116 of 340 eligible participants, a peripheral venous aldosterone measurement was obtained at this time. Patients were transported to the interventional radiology suite approximately 2 hours after this blood draw and received intravenous fentanyl and midazolam to induce conscious sedation after which the AVS procedure commenced.

The AVS protocol is illustrated in Figure 1. A catheter was inserted through a femoral vein and positioned in the infrarenal IVC to obtain baseline unstimulated measurements of aldosterone and cortisol. Two separate catheters were then used to cannulate the right and left adrenal veins, the locations of which were visually confirmed using adrenal venography and/or adjunctive cone-beam computed tomography. The catheters remained in place for all sampling and stable catheter position was confirmed via intermittent adrenal venography, which did not impact the timing at which samples were obtained. Measurements of aldosterone and cortisol were obtained simultaneously, and in triplicate, 5 minutes apart. These triplicate unstimulated aldosterone and cortisol values were used to calculate the lateralization index; the lateralization index was not calculated after stimulation with cosyntropin adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) since this method has been shown to decrease the lateralization index and result in erroneous subtyping.14–17

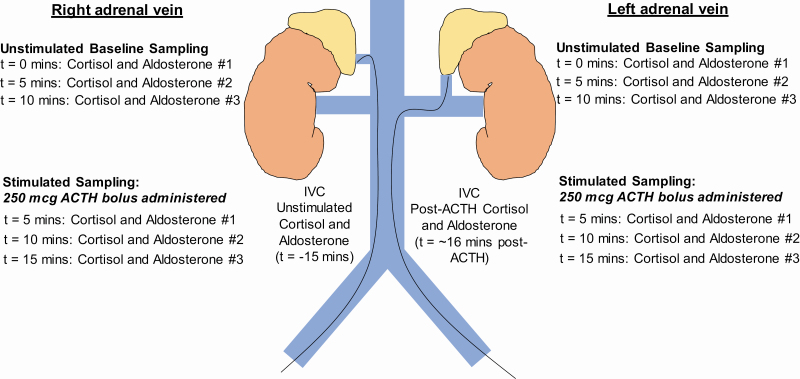

Figure 1.

AVS protocol with simultaneous and triplicate sampling. AVS began with cannulation of the femoral veins and measurement of the unstimulated aldosterone and cortisol in the IVC (t = −15 minutes). Two catheters were then threaded into the bilateral adrenal veins and confirmed using adrenal venography and adjunctive cone-beam computed tomography, in a process that typically took 15 minutes. Once the bilateral adrenal venous catheters were in place, measurements of unstimulated aldosterone and cortisol were obtained simultaneously from the bilateral adrenal veins every 5 minutes for a total of 3 samples each. With the adrenal vein catheters still in place, a single intravenous injection of 250 mcg of ACTH was then administered and simultaneous measurements of stimulated aldosterone and cortisol were obtained 5, 10, and 15 minutes after the ACTH injection. Once the final stimulated samples were obtained from each adrenal vein, the catheters were withdrawn and a final stimulated sample of aldosterone and cortisol was obtained from the IVC. Abbreviation: AVS, adrenal venous sampling.

After the third unstimulated measurement of aldosterone and cortisol was obtained from each adrenal vein, a single 250 mcg bolus of intravenous ACTH was administered via peripheral vein in order to enhance and calculate the stimulated SI. Five minutes after ACTH was administered, ACTH-stimulated aldosterone and cortisol levels were obtained from each adrenal vein, in triplicate, 5 minutes apart. The AVS procedure concluded with measurement of the ACTH-stimulated cortisol and aldosterone from the IVC approximately 16 minutes after the ACTH injection was administered.

After completion of AVS, patients were sent back to their referring clinicians who used the lateralization data to discuss individualized treatment options with their patients, which included unilateral adrenalectomy, unilateral radiofrequency ablation, or medical therapy.

Measurements

Aldosterone concentrations were measured using the Quest Diagnostics liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) assay with a laboratory-reported coefficient of variation (CV) ranging from 2.7% to 4.4% depending on the aldosterone value (CV of 3.8% in the lowest analytical level [mean aldosterone = 11.4 ng/dl] and CV of 3.2% in the highest analytical level [mean aldosterone = 995 ng/dl]). From 2017 to 2019, cortisol levels were measured using the Elecsys Cortisol II immunoassay (Roche) and cobas e601 analyzer, with a laboratory-reported CV ranging from 1.5% to 5.4% (CV of 5.4% in the lowest analytical level [mean cortisol = 0.131 µg/dl] and CV of 1.6% in the highest analytical level [mean cortisol = 60.2 µg/dl]). From 2005 to 2017, cortisol levels were measured using the Elecsys Cortisol I immunoassay (Roche) with similar CV values.

Study objectives and statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted to assess the variability of aldosterone using 2 approaches:

1) Acute changes in circulating venous aldosterone levels: The acute change in systemic circulating aldosterone concentrations was assessed from the time of pre-AVS peripheral measurement to the time of IVC measurement at the initiation of AVS (approximately 2 hours later) in the subset of 116 patients.

2) Acute changes in adrenal venous aldosterone levels: The variability in the simultaneous and triplicate unstimulated adrenal venous aldosterone values measured within a 10-minute interval was assessed in the entire cohort.

As per clinical custom, aldosterone-to-cortisol (A/C) ratios were calculated for each paired measurement from both adrenal veins. Similarly, the lateralization index was calculated for each patient, defined as the unstimulated mean A/C ratio from the dominant adrenal vein divided by the unstimulated mean A/C ratio from the contralateral adrenal vein. As international practices differ as to which unstimulated lateralization index threshold to use, we defined laterality using an unstimulated lateralization index of ≥2 and also separately a more conservative threshold of ≥4. Post-treatment outcomes were analyzed for patients with at least 1 follow-up appointment. Patients who underwent unilateral surgical adrenalectomy or radiofrequency ablation were classified as having absent, partial, or complete clinical and biochemical success as per the Primary Aldosteronism Surgical Outcomes study (PASO) criteria.18

Means are presented with standard deviations for normally distributed variables. Medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) are presented for non-normally distributed variables. Paired and unpaired t-tests were used to assess differences between aldosterone, cortisol, and A/C ratio values for normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for such comparisons if the data were nonparametric. Chi-squared tests and analysis of variance were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively, between 3 groups; if data were nonparametric, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used in place of analysis of variance. Spearman’s correlation was used to assess relations between nonparametric variables. CVs, defined as the standard deviation divided by the mean, were calculated for each set of triplicate measurements from each adrenal vein to quantify the degree of acute variation. The percent difference, defined as the difference between the highest and lowest value in a triplicate divided by the average value of the triplicate, was also calculated as an alternative metric of variability. To determine the clinical impact of aldosterone variability, lateralization indices were recalculated in 2 ways:

1) by using only the first of 3 unstimulated aldosterone-to-cortisol ratios in each adrenal vein, as would be done in protocols that use only one single simultaneous adrenal vein sample, and

2) by using the lowest unstimulated aldosterone-to-cortisol ratio on the dominant side and highest ratio on the contralateral side, instead of averaging the 3 separate ratios in a triplicate, as could occur in a protocol that employed sequential adrenal vein sampling.

Analyses were conducted using STATA version 15 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study population characteristics

Baseline information of the study population is reported in Table 1. On average, patients were hypertensive despite the use of 3 antihypertensive medications, and were hypokalemic and had elevated aldosterone-to-renin ratios. The majority had imaging evidence of at least 1 adrenal nodule. Although patients were hypokalemic on average at the time of diagnosis, the mean potassium on the day of AVS was normal, 3.9 mEq/l, since potassium supplementation was instituted following diagnosis and prior to AVS. The characteristics of the subset with peripheral aldosterone measurements immediately before the start of AVS were not significantly different than those of the overall study population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | Total study population (n = 340) | Subset with pre-AVS peripheral aldosterone measurements (n = 116) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53 (11) | 54 (11) |

| Male sex (%) | 64% | 69% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 50% | 50% |

| Black | 19% | 21% |

| Asian | 6% | 4% |

| Other/unknown | 25% | 25% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31 (6) | 32 (7) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 149 (21) | 148 (18) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 87 (13) | 84 (11) |

| Potassium at diagnosis (mEq/l) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.4 (0.5) |

| Potassium on day of AVS (mEq/l) | 3.9 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.7) |

| Plasma renin activity (ng/ml/h) | 0.5 [0.2–0.6] | 0.3 [0.1–0.6] |

| Plasma aldosterone concentration (ng/dl) | 22.8 [16.7–34.0] | 20.8 [17.0–30.0] |

| Aldosterone-to-renin ratio [(ng/dl)/(ng/ ml/h)] | 70 [35–160] | 77 [38–194] |

| Number of antihypertensive medications | 3 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Cross-sectional imaging findings | ||

| Normal | 16% | 20% |

| Unilateral left nodule | 41% | 36% |

| Unilateral right nodule | 35% | 35% |

| Bilateral abnormalities | 8% | 9% |

Mean (SD) reported for parametric data. Median [IQR] reported for nonparametric data. Abbreviations: AVS, adrenal venous sampling; BMI, body mass index.

Acute changes in circulating venous aldosterone levels (analysis 1)

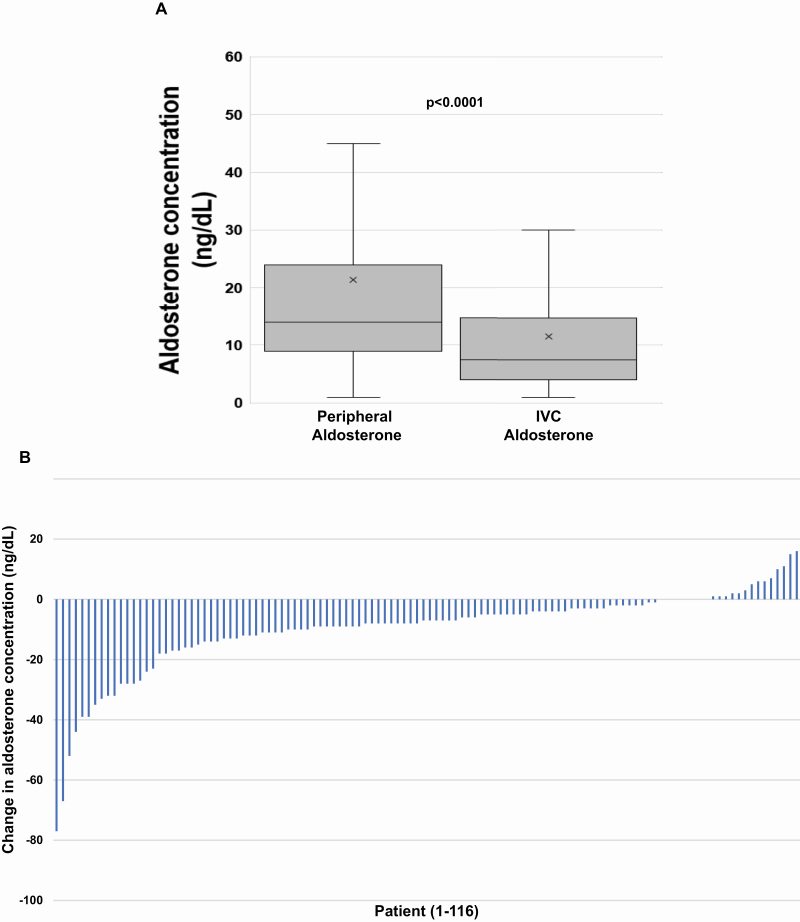

On the day of AVS, within an average time frame of 131 (SD = 47) minutes, the circulating venous aldosterone concentration declined in most patients, 81% (94/116), from pre-AVS to the initiation of AVS. The median venous aldosterone concentration before AVS was 14.0 (IQR 9.0–24.0) ng/dl and declined significantly to a median of 7.5 (IQR 4.0–14.5) ng/dl at the beginning of AVS within this 2-hour interval (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2a and b). The median absolute change in venous aldosterone from pre-AVS to initiation of AVS during this time interval was a decrease of 7.0 (IQR 2.0–12.5) ng/dl and the median relative change in aldosterone was a decrease of 51% (IQR 20–72%). The magnitude of the decrease in aldosterone was similar regardless of whether the patient proved to have unilateral or bilateral disease at AVS. There was no association between the acute change in aldosterone concentrations and the time elapsed between peripheral and IVC aldosterone measurements (Supplementary Figure S1A and B online).

Figure 2.

Comparison of peripheral and IVC aldosterone levels at AVS. (a) Box-and-whisker plot of peripheral vs. IVC aldosterone levels on the day of AVS. Among the subset of 116 patients with a peripheral venous aldosterone level on the day of AVS, the median peripheral aldosterone value was 14.0 ng/dl and the median IVC aldosterone value was 7.5 ng/dl (P < 0.0001 by Wilcoxon signed rank test). The median absolute change in aldosterone was a decrease of 7.0 ng/dl and the median percentage change in aldosterone was a decrease of 51%. (b) Waterfall plot of absolute change in aldosterone concentration on the day of AVS. The absolute change in aldosterone (IVC aldosterone–peripheral aldosterone, y axis) on the day of AVS is depicted for each individual patient (x axis). 81% of patients (94/116) had a lower aldosterone level in the IVC compared with a peripheral venous level drawn approximately 2 hours earlier. Abbreviation: AVS, adrenal venous sampling.

Strikingly, the unstimulated aldosterone concentration in the IVC at the start of AVS was less than or equal to 5 ng/dl in 47% (44/94) of the patients who had a decrease in peripheral to IVC aldosterone levels on the day of AVS, and in 26% (90/340) of the total cohort of patients. Patients who exhibited these very low aldosterone levels during AVS appeared to have a milder form of primary aldosteronism, characterized by lower aldosterone levels and aldosterone-to-renin ratios, and higher potassium (Supplementary Tables S1A and 1B online).

Acute changes in adrenal venous aldosterone levels (analysis 2)

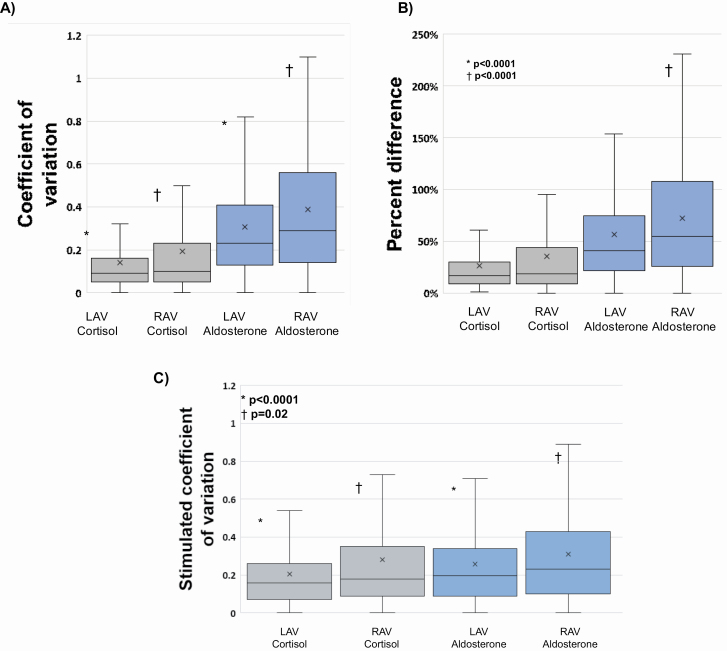

Aldosterone measurements were highly variable within each set of triplicate and simultaneous adrenal vein measurements. The mean unstimulated CV for aldosterone was 30% in the left adrenal vein and 39% in the right adrenal vein. In contrast, the mean unstimulated CV for cortisol was 14% in the left adrenal vein and 19% in the right adrenal vein (P < 0.0001) (Figure 3a). When the 3 unstimulated A/C ratios in each adrenal vein were analyzed, the mean CV was 29% in the left adrenal vein and 35% in the right adrenal vein. The mean percent difference of aldosterone followed a similar pattern: 57% and 73% in the left and right adrenal veins, respectively, and a mean cortisol percent difference of 27% and 35% in the left and right adrenal veins, respectively (P < 0.0001) (Figure 3b). The percent difference of the A/C ratios was 54% on the left and 65% on the right. As expected, following a bolus of ACTH, the stimulated CV of adrenal venous aldosterone concentrations decreased to 26% (from 30%, P = 0.009) in the left adrenal vein and decreased to 31% (from 39%, P = 0.0008) in the right adrenal vein; however, these CVs were still significantly higher than the stimulated CV of cortisol in each adrenal vein (P < 0.0001 in left adrenal vein and P = 0.02 in right adrenal vein) (Figure 3c). After ACTH stimulation, the CV of the A/C ratios was 20% on the left and 24% on the right. These findings were consistent even when different definitions of selectivity were employed (Supplementary Tables S2A and 2B online). All of these findings were also similar regardless of disease laterality at AVS.

Figure 3.

Variation in adrenal vein triplicate samples. (a) Coefficients of variation (CVs) for unstimulated (pre-ACTH) cortisol and aldosterone. CVs were defined as the standard deviation of the 3 adrenal vein aldosterone or cortisol values within a triplicate divided by the mean aldosterone or cortisol within that triplicate. The mean unstimulated CV of aldosterone in the left adrenal vein was 30%, which was significantly higher than that of cortisol (14%) in the left adrenal vein (*P < 0.0001). The mean unstimulated CV of aldosterone in the right adrenal vein was 39%, also significantly higher than that of cortisol (19%) in the right adrenal vein (†P < 0.0001). Abbreviations: LAV, left adrenal vein; RAV, right adrenal vein. (b) Percent difference for unstimulated (pre-ACTH) cortisol and aldosterone. The percent difference was defined as the difference between the highest and lowest aldosterone or cortisol values within an adrenal vein triplicate divided by the average aldosterone or cortisol value of the triplicate. The mean percent difference of aldosterone in the left adrenal vein was 57%, whereas the mean percent difference of cortisol in the left adrenal vein was 27% (*P < 0.0001). In the right adrenal vein, the mean percent difference of aldosterone was 73% vs. 35% for cortisol (†P < 0.0001). (c) The stimulated (post-ACTH) CV of aldosterone and cortisol in each adrenal vein. In the left adrenal vein, the mean CV of aldosterone was 26% compared with 20% for cortisol (*P < 0.0001). In the right adrenal vein, the mean CV of aldosterone was 31% vs. 28% for cortisol (†P = 0.02).

Clinical implications of acute adrenal venous changes in aldosterone

The use of triplicate sampling in our protocol permitted averaging of measurements to approximate a true mean. If the lateralization index were recalculated using only the first A/C ratio on each side (i.e., just the first measurement rather than the mean of all 3), a scenario analogous to performing AVS with single simultaneous sampling, the interpretation of the AVS would have been discordant in 8–10% of cases depending on the lateralization index threshold used (Table 2). The lateralization index using the first simultaneous adrenal vein samples averaged across all patients was no different from the average lateralization indices using the second or third unstimulated samples (first: 7.6 [IQR 2.5–25.2] vs. second: 8.1 [IQR 2.5–24.1] vs. third: 8.1 [IQR 2.5–24.6]; P = 0.97).

Table 2.

Interpretations of AVS comparing the mean of triplicate sampling vs. the first aldosterone-to-cortisol ratios

| Laterality based on first A/C on each side (lateralization index ≥2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral | Left | Right | Total | ||

| Laterality based on average of 3 A/C on each side (lateralization index ≥2) | Bilateral | 44 (12.9%) | 11 (3.2%) | 7 (2.1%) | 62 |

| Left | 4 (1.2%) | 119 (35.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 124 | |

| Right | 10 (2.9%) | 0 | 144 (42.4%) | 154 | |

| Total | 58 | 130 | 152 | 340 | |

| Laterality based on first A/C on each side(lateralization index ≥ 4) | |||||

| Bilateral | Left | Right | Total | ||

| Laterality based on average of 3 A/C on each side (lateralization index ≥4) | Bilateral | 104 (30.6%) | 6 (1.8%) | 6 (1.8%) | 116 |

| Left | 4 (1.1%) | 98 (28.8%) | 0 | 102 | |

| Right | 11 (3.2%) | 0 | 111 (32.6%) | 122 | |

| Total | 119 | 104 | 117 | 340 | |

Lateralization calculated using the average of 3 unstimulated aldosterone-to-cortisol ratios in each adrenal vein (displayed in the rows) is compared with lateralization calculated on the basis of the first of 3 (i.e., at time = 0 minute) aldosterone-to-cortisol ratios in the dominant adrenal vein divided by the first of 3 aldosterone-to-cortisol ratios in the contralateral adrenal vein (displayed in the columns). The top half of the table uses an unstimulated lateralization index of ≥2 to classify laterality whereas the bottom half of the table uses a lateralization index cutoff of ≥4. Bolded and italicized values highlight subjects with discordant lateralization. Abbreviation: AVS, adrenal venous sampling.

If the lateralization index were derived using the single lowest of the 3 A/C ratios on the dominant side (numerator), and the highest of the 3 ratios on the contralateral side (denominator), a scenario that could occur in AVS protocols that employ sequential sampling of the adrenal veins, the interpretation of the AVS would have been discordant in 16–17% of cases depending on the lateralization index threshold used (Table 3), with most discordance explained by unilateral disease being reclassified as bilateral. Similar discordance rates were seen when the lateralization index was recalculated using the single highest A/C ratio in the numerator and single lowest ratio in the denominator, but with bilateral disease becoming unilateral (Supplementary Table S3 online).

Table 3.

Interpretations of AVS comparing the mean of triplicate sampling vs. the lowest-to-highest aldosterone-to-cortisol ratios

| Laterality based on lowest A/C on dominant side and highest A/C on nondominant side (lateralization index ≥2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral | Left | Right | Total | ||

| Laterality based on average of 3 A/C on each side (lateralization index ≥2) | Bilateral | 61 (17.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | 62 |

| Left | 16 (4.7%) | 108 (31.8%) | 0 | 124 | |

| Right | 42 (12.4%) | 0 | 112 (32.9%) | 154 | |

| Total | 119 | 109 | 112 | 340 | |

| Laterality based on lowest A/C on dominant side and highest A/C on nondominant side (lateralization index ≥4) | |||||

| Bilateral | Left | Right | Total | ||

| Laterality based on average of 3 A/C on each side (lateralization index ≥4) | Bilateral | 114 (33.5%) | 2 (0.6%) | 0 | 116 |

| Left | 19 (5.6%) | 83 (24.4%) | 0 | 102 | |

| Right | 33 (9.7%) | 0 | 89 (26.2%) | 122 | |

| Total | 166 | 85 | 89 | 340 | |

Lateralization calculated using the average of 3 unstimulated aldosterone-to-cortisol ratios in each adrenal vein (displayed in the rows) is compared with lateralization calculated on the basis of the single lowest aldosterone-to-cortisol ratio in the dominant adrenal vein divided by the single highest aldosterone-to-cortisol ratio in the contralateral adrenal vein (displayed in the columns). The top half of the table uses an unstimulated lateralization index of ≥2 to classify laterality whereas the bottom half of the table uses a lateralization index cutoff of ≥4. Bolded and italicized values highlight subjects with discordant lateralization. Abbreviation: AVS, adrenal venous sampling.

Treatment outcomes

Of the patients with a lateralization index of ≥2 and in whom treatment modality was known, 79% (143/180) were treated with either unilateral adrenalectomy or unilateral radiofrequency ablation at the time of this analysis; of the patients with a lateralization index of ≥4 in whom treatment modality was known, 88% (130/148) were treated with a unilateral intervention. Of the 216 total patients in whom treatment modality was known, 52% (n = 113) had surgical adrenalectomy, 17% (n = 36) underwent radiofrequency ablation, and 31% (n = 67) were treated with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist. Unilateral intervention resulted in less antihypertensive medication use and a trend toward a lower systolic blood pressure compared with medical treatment (Supplementary Table S4 online). There were no notable associations between the unstimulated IVC aldosterone concentration or the decrease in aldosterone on the day of AVS and post-treatment outcomes to unilateral intervention or medical therapy (Supplementary Tables S5A and 5B online). Of the patients who underwent either unilateral surgical adrenalectomy or radiofrequency ablation and whose postintervention outcomes were available, 83% (98/118) achieved either complete or partial clinical success and 93% (57/61) achieved either complete or partial biochemical success per PASO criteria.18 There was no difference in unilateral intervention outcome per PASO criteria based on the unstimulated IVC aldosterone concentration or decrease in circulating aldosterone levels on the day of AVS.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe 2 separate, though potentially related phenomena that highlight the variable nature of aldosterone measurements in primary aldosteronism. First, even though patients with primary aldosteronism are considered to have nonsuppressible and autonomous aldosterone production, we observed that 81% of patients had a substantial decrease in circulating aldosterone concentrations while lying supine for a few hours on the day of AVS, and strikingly, a quarter of all patients had an inferior vena cava aldosterone of less than or equal to 5 ng/dl, a level usually considered to be incompatible with a diagnosis of primary aldosteronism. This finding extends observations from prior studies,6–8,11 and underscores that patients with primary aldosteronism need not have “high” aldosterone concentrations at all times; this appeared to be especially true for patients with milder forms of primary aldosteronism characterized by lower aldosterone levels and aldosterone-to-renin ratios, and higher potassium levels. Second, our study demonstrates the acute variability of aldosterone concentrations during AVS. In a span of 10 minutes, we observed substantial variations in adrenal venous aldosterone concentrations such that reliance on a single measurement could have resulted in misclassification of lateralization in up to 17% of patients. Collectively, our findings expand the growing body of evidence describing variability of aldosterone levels in primary aldosteronism and how they may impact clinical care.

Prior studies that employed frequent sampling, in healthy volunteers and patients with primary aldosteronism, have shown that circulating aldosterone concentrations exhibit diurnal variation but also burst-like pulsatility throughout the day.6,7 This phenomenon has been shown to lead to uncharacteristically low aldosterone levels even in patients with bona fide primary aldosteronism, which may at times obfuscate the diagnosis.8–11 Our current study advances these prior observations by demonstrating the relative magnitude and temporality of aldosterone variation in the context of AVS. Some possibilities we considered to explain the mechanism for this acute aldosterone variability and unexpectedly low levels include:

1) Posture: The maintenance of prolonged supine posture to remove any stimulation by angiotensin II. Although patients with primary aldosteronism do not typically undergo testing while supine (apart from at the time of AVS), a more practical corollary for this physiology is consumption of a high sodium diet which could also further suppress angiotensin II via volume expansion. In this regard, the low aldosterone levels we observed could be describing various phenotypes of angiotensin II sensitivity that have been previously observed.19,20

2) Disease severity: Related to the first point, patients who had a more significant decrease in aldosterone levels on the day of AVS, and/or very low IVC aldosterone levels during AVS, appeared to have a milder form of primary aldosteronism. This phenomenon may also provide an explanation for why many mild cases of primary aldosteronism evade detection, as single aldosterone values can, at times, be low enough to incorrectly exclude the diagnosis.8

3) Diurnal variation: At first glance, it may seem intuitive that aldosterone levels would decrease in the approximately 2 hours between the peripheral aldosterone blood draw and cannulation of the inferior vena cava due to the diurnal rhythm of aldosterone secretion. Although potentially contributory, there was no difference between the absolute or relative change in aldosterone and the time difference between measurements (Supplementary Figure S1A and B online). Thus, our observations appear to reflect a phenomenon apart from the effect of time.

4) Variable secretion and/or responsiveness to ACTH: ACTH is a known secretagogue of aldosterone21–23 and could have had variable secretion during the AVS procedure and each focus of aldosterone production could respond uniquely to ACTH inputs. Indeed, when patients in our study were assessed after supraphysiologic ACTH stimulation, the relative variability of adrenal venous aldosterone production was decreased, highlighting the known utility of ACTH in stabilizing variability (beyond enhancing the SI). Some patients with primary aldosteronism have cortisol cosecretion24—whether this could influence ACTH and AVS interpretations is unclear; however, 1 recent study suggests AVS interpretations are not likely to be affected.25

5) The use of sedatives to induce conscious sedation: There are only limited data to suggest that opioids and benzodiazepines may directly impact aldosterone production at the level of the adrenal gland.26,27 However, it is possible that the induction of conscious sedation may have diminished ACTH, as discussed above.

6) Technical aspects related to adrenal venous catheter placement: Aldosterone concentrations can vary depending on the specific location within the central adrenal veins or upstream tributary veins in which the catheters are placed.28,29 Although we ensured stable catheter position (see Methods), small micromovements may have contributed, in part, to some variability in aldosterone concentrations.

Regardless of the mechanism, the finding that aldosterone is markedly lowered in the vast majority of patients over a short period of time during a common diagnostic procedure for primary aldosteronism has important clinical implications. AVS is recommended to assess laterality of disease in primary aldosteronism to determine the most appropriate definitive treatment.12 Since surgical cure of primary aldosteronism may be superior to chronic medical therapy, accurate identification of unilateral disease is critical.30–37 Our findings demonstrate the importance of integrating multiple aldosterone measurements from each adrenal vein, as each measurement can differ from other measurements by as much as 73% within 10 minutes (Figure 3b), a fact that could have changed lateralization in 17% of patients if single (instead of triplicate) measures were obtained—a potentially missed opportunity to diagnose surgically curable primary aldosteronism. The variability of aldosterone we observed was far higher than expected based on the intrinsic characteristics of the lab assay itself, and indeed higher than that of cortisol despite a similar CV of the assay used. While the aldosterone assay used in this study was LC–MS/MS, it is important to note that some centers use aldosterone immunoassays, which tend to be less precise and may be associated with even higher aldosterone variability than that observed in this study.

We recognize that AVS protocols differ considerably from institution to institution and country to country. Although “expert” AVS centers often obtain multiple and simultaneous samples, most AVS procedures in the world are not performed by these expert centers, and a variety of protocols are used, including only single measurements of aldosterone and cortisol from each adrenal vein, either simultaneously or sequentially.15 We are aware of 1 retrospective study comparing sequential with simultaneous AVS which found similar results between the 2 methods, although the simultaneous protocol in the referenced study used duplicate instead of triplicate sampling.38 Our results underscore the value of repeated and simultaneous adrenal vein sampling rather than relying on protocols that utilize sequential and/or single sampling.

One limitation of this study is that the variability in aldosterone levels is likely to reflect a combination of the imprecision of the assay and intrinsic intraindividual biologic factors. The combination of these 2 variables contribute to the overall CV of aldosterone measurements we observed, and may be incorporated in a statistical model to yield the reference change value, which reflects whether the difference between 2 or more measurements is real or simply due to variation from analytical or biologic processes.39,40 Our study was not designed to calculate the reference change value or disentangle the influences of assay variability and intrinsic biological variability on the final clinical results; however, the fact that our observed CV of aldosterone was significantly higher than the established CV of the assay in all ranges indicates a substantial component of intraindividual variation in aldosterone production. Ultimately, regardless of the cause of the variation, the results are clinically relevant as they have the potential to influence patient care. A second limitation of the study is that a pre-AVS aldosterone level was obtained in only 34% (n = 116) of the study population. However, as the baseline characteristics of this relatively large subgroup and the entire cohort were similar, this is unlikely to have affected the results. A third limitation of the study is that it was designed to observe the variability in aldosterone production only on the day of AVS, and how these findings translate to ambulatory seated variations was not directly assessed herein. A fourth limitation is that our study was not specifically designed to investigate the effect of aldosterone variability on outcomes. However, it is reassuring that the clinical and biochemical outcomes of patients who lateralized at AVS and underwent unilateral intervention were consistent with published reports.18 A fifth limitation is that our study was not designed to investigate the mechanism underlying our observations, specifically whether the specific agents used for conscious sedation had any contribution to aldosterone variability. Finally, although mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists were discontinued in all patients several weeks prior to AVS, nearly all patients were on some form of antihypertensive therapy at the time of AVS, including those that may lower aldosterone levels such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers. We acknowledge that some experts recommend discontinuation of all antihypertensive medications prior to undergoing AVS or switching to such medications as alpha blockers or hydralazine which have less impact on the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system; however, this is not the general practice in tertiary care centers in the United States, and therefore, our findings are practically relevant in our country.

In conclusion, circulating aldosterone concentrations can vary substantially during AVS for primary aldosteronism, often to levels well below the traditional thresholds considered to be compatible with the diagnosis. Future studies should evaluate the impact of this aldosterone variability on diagnostic accuracy. Further, aldosterone concentrations exhibit substantial acute variability during AVS; these variations could induce erroneous interpretations of subtype differentiation in many instances if relying upon a single adrenal venous aldosterone measurement. These findings underscore the expanding evidence that has observed pulsatile and variable aldosterone concentrations in primary aldosteronism and suggest that relying on single venous aldosterone levels lacks precision and reproducibility; routinely obtaining multiple and/or integrated aldosterone measurements during diagnostic testing and AVS may provide more reliable interpretations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the interventional radiology staff that assisted with adrenal venous sampling protocols and clinical research center staff that assisted with specimen processing and storage.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK115392, R01 DK16618 and R01 HL153004 (A.V.) and 2T32 HL007609-32 (N.Y.).

DISCLOSURE

AV reports consulting fees unrelated to the contents of this work from Corcept Therapeutics, CatalysPacific, HRA Pharma. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1. Monticone S, Burrello J, Tizzani D, Bertello C, Viola A, Buffolo F, Gabetti L, Mengozzi G, Williams TA, Rabbia F, Veglio F, Mulatero P. Prevalence and clinical manifestations of primary aldosteronism encountered in primary care practice. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69:1811–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rossi GP, Bernini G, Caliumi C, Desideri G, Fabris B, Ferri C, Ganzaroli C, Giacchetti G, Letizia C, Maccario M, Mallamaci F, Mannelli M, Mattarello MJ, Moretti A, Palumbo G, Parenti G, Porteri E, Semplicini A, Rizzoni D, Rossi E, Boscaro M, Pessina AC, Mantero F; PAPY Study Investigators A prospective study of the prevalence of primary aldosteronism in 1,125 hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48:2293–2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Markou A, Pappa T, Kaltsas G, Gouli A, Mitsakis K, Tsounas P, Prevoli A, Tsiavos V, Papanastasiou L, Zografos G, Chrousos GP, Piaditis GP. Evidence of primary aldosteronism in a predominantly female cohort of normotensive individuals: a very high odds ratio for progression into arterial hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98:1409–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Calhoun DA, Nishizaka MK, Zaman MA, Thakkar RB, Weissmann P. Hyperaldosteronism among black and white subjects with resistant hypertension. Hypertension 2002; 40:892–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vaidya A, Mulatero P, Baudrand R, Adler GK. The expanding spectrum of primary aldosteronism: implications for diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. Endocr Rev 2018; 39:1057–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vieweg WV, Veldhuis JD, Carey RM. Temporal pattern of renin and aldosterone secretion in men: effects of sodium balance. Am J Physiol 1992; 262:F871–F877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siragy HM, Vieweg WV, Pincus S, Veldhuis JD. Increased disorderliness and amplified basal and pulsatile aldosterone secretion in patients with primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tanabe A, Naruse M, Takagi S, Tsuchiya K, Imaki T, Takano K. Variability in the renin/aldosterone profile under random and standardized sampling conditions in primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88:2489–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown JM, Siddiqui M, Calhoun DA, Carey RM, Hopkins PN, Williams GH, Vaidya A. Web Exclusive. The unrecognized prevalence of primary aldosteronism. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173:10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Funder JW Primary aldosteronism: at the tipping point. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173:65–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kline GA, Darras P, Leung AA, So B, Chin A, Holmes DT. Surprisingly low aldosterone levels in peripheral veins following intravenous sedation during adrenal vein sampling: implications for the concept of nonsuppressibility in primary aldosteronism. J Hypertens 2019; 37:596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Funder JW, Carey RM, Mantero F, Murad MH, Reincke M, Shibata H, Stowasser M, Young WF Jr. The management of primary aldosteronism: case detection, diagnosis, and treatment: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101:1889–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rossi GP, Auchus RJ, Brown M, Lenders JW, Naruse M, Plouin PF, Satoh F, Young WF Jr. An expert consensus statement on use of adrenal vein sampling for the subtyping of primary aldosteronism. Hypertension 2014; 63:151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yatabe M, Bokuda K, Yamashita K, Morimoto S, Yatabe J, Seki Y, Watanabe D, Morita S, Sakai S, Ichihara A. Cosyntropin stimulation in adrenal vein sampling improves the judgment of successful adrenal vein catheterization and outcome prediction for primary aldosteronism. Hypertens Res 2020; 43:1105–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rossitto G, Amar L, Azizi M, Riester A, Reincke M, Degenhart C, Widimsky J, Naruse M, Deinum J, Schultzekool L, Kocjan T, Negro A, Rossi E, Kline G, Tanabe A, Satoh F, Rump LC, Vonend O, Willenberg HS, Fuller P, Yang J, Nian Chee NY, Magill SB, Shafigullina Z, Quinkler M, Oliveras A, Chang C-C, Wu VC, Somloova Z, Maiolino G, Barbiero G, Battistel M, Lenzini L, Quaia E, Pessina AC, Rossi GP. Subtyping of primary aldosteronism in the AVIS-2 study: assessment of selectivity and lateralization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020; 105; 6:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. St-Jean M, Bourdeau I, Therasse É, Lacroix A. Use of peripheral plasma aldosterone concentration and response to ACTH during simultaneous bilateral adrenal veins sampling to predict the source of aldosterone secretion in primary aldosteronism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2020; 92:187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wannachalee T, Zhao L, Nanba K, Nanba AT, Shields JJ, Rainey WE, Auchus RJ, Turcu AF. Three discrete patterns of primary aldosteronism lateralization in response to cosyntropin during adrenal vein sampling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019; 104:5867–5876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams TA, Lenders JW, Mulatero P, Burrello J, Rottenkolber M, Adolf C, Satoh F, Amar L, Quinkler M, Deinum J, Beuschlein F, Kitamoto KK, Pham U, Morimoto R, Umakoshi H, Prejbisz A, Kocjan T, Naruse M, Stowasser M, Nishikawa T, Young WF, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Funder JW, Reincke M. Outcome of adrenalectomy for unilateral primary aldosteronism: international consensus and remission rates. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017; 5:689–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tunny TJ, Klemm SA, Stowasser M, Gordon RD. Angiotensin-responsive aldosterone-producing adenomas: postoperative disappearance of aldosterone response to angiotensin. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1993; 20:306–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guo Z, Nanba K, Udager A, McWhinney BC, Ungerer JPJ, Wolley M, Thuzar M, Gordon RD, Rainey WE, Stowasser M. Biochemical, histopathological and genetic characterization of posture responsive and unresponsive APAs. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020; 105:e3224–e3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Markou A, Sertedaki A, Kaltsas G, Androulakis II, Marakaki C, Pappa T, Gouli A, Papanastasiou L, Fountoulakis S, Zacharoulis A, Karavidas A, Ragkou D, Charmandari E, Chrousos GP, Piaditis GP. Stress-induced aldosterone hyper-secretion in a substantial subset of patients with essential hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100:2857–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Daimon M, Kamba A, Murakami H, Takahashi K, Otaka H, Makita K, Yanagimachi M, Terui K, Kageyama K, Nigawara T, Sawada K, Takahashi I, Nakaji S. Association between pituitary-adrenal axis dominance over the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101:889–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. El Ghorayeb N, Bourdeau I, Lacroix A. Role of ACTH and other hormones in the regulation of aldosterone production in primary aldosteronism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2016; 7:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arlt W, Lang K, Sitch AJ, Dietz AS, Rhayem Y, Bancos I, Feuchtinger A, Chortis V, Gilligan LC, Ludwig P, Riester A, Asbach E, Hughes BA, O’Neil DM, Bidlingmaier M, Tomlinson JW, Hassan-Smith ZK, Rees DA, Adolf C, Hahner S, Quinkler M, Dekkers T, Deinum J, Biehl M, Keevil BG, Shackleton CH, Deeks JJ, Walch AK, Beuschlein F, Reincke M. Steroid metabolome analysis reveals prevalent glucocorticoid excess in primary aldosteronism. JCI Insight 2017; 2:e93136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O’Toole SM, Sze W-CC, Chung T-T, Akker SA, Druce MR, Waterhouse M, Pitkin S, Dawnay A, Sahdev A, Matson M, Parvanta L, Drake WM. Low grade cortisol co-secretion has limited impact on ACTH-stimulated AVS parameters in primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020; 105:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fallo F, Boscaro M, Sonino N, Mantero F. Effect of naloxone on the adrenal cortex in primary aldosteronism. Am J Hypertens 1988; 1:280–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shibata H, Kojima I, Ogata E. Diazepam inhibits potassium-induced aldosterone secretion in adrenal glomerulosa cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1986; 135:994–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Satani N, Ota H, Seiji K, Morimoto R, Kudo M, Iwakura Y, Ono Y, Nezu M, Omata K, Ito S, Satoh F, Takase K. Intra-adrenal aldosterone secretion: segmental adrenal venous sampling for localization. Radiology 2016; 278:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Makita K, Nishimoto K, Kiriyama-Kitamoto K, Karashima S, Seki T, Yasuda M, Matsui S, Omura M, Nishikawa T. A novel method: super-selective adrenal venous sampling. J Vis Exp 2017; 55716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hundemer GL, Curhan GC, Yozamp N, Wang M, Vaidya A. Cardiometabolic outcomes and mortality in medically treated primary aldosteronism: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6:51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rossi GP, Rossitto G, Amar L, Azizi M, Riester A, Reincke M, Degenhart C, Widimsky J Jr, Naruse M, Deinum J, Schultze Kool L, Kocjan T, Negro A, Rossi E, Kline G, Tanabe A, Satoh F, Christian Rump L, Vonend O, Willenberg HS, Fuller PJ, Yang J, Chee NYN, Magill SB, Shafigullina Z, Quinkler M, Oliveras A, Dun Wu K, Wu VC, Kratka Z, Barbiero G, Battistel M, Chang CC, Vanderriele PE, Pessina AC. Clinical outcomes of 1625 patients with primary aldosteronism subtyped with adrenal vein sampling. Hypertension 2019; 74:800–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kline GA, Pasieka JL, Harvey A, So B, Dias VC. Medical or surgical therapy for primary aldosteronism: post-treatment follow-up as a surrogate measure of comparative outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20:2274–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hundemer Gregory L, Curhan Gary C, Yozamp Nicholas, Wang Molin, Vaidya Anand. Renal outcomes in medically and surgically treated primary aldosteronism. Hypertension 2018; 72:658–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hundemer GL, Curhan GC, Yozamp N, Wang M, Vaidya A. Incidence of atrial fibrillation and mineralocorticoid receptor activity in patients with medically and surgically treated primary aldosteronism. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3:768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meng X, Ma WJ, Jiang XJ, Lu PP, Zhang Y, Fan P, Cai J, Zhang HM, Song L, Wu HY, Zhou XL, Lou Y. Long-term blood pressure outcomes of patients with adrenal venous sampling-proven unilateral primary aldosteronism. J Hum Hypertens 2020; 34:440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Indra T, Holaj R, Štrauch B, Rosa J, Petrák O, Šomlóová Z, Widimský J Jr. Long-term effects of adrenalectomy or spironolactone on blood pressure control and regression of left ventricle hypertrophy in patients with primary aldosteronism. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2015; 16:1109–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Velema M, Dekkers T, Hermus A, Timmers H, Lenders J, Groenewoud H, Schultze Kool L, Langenhuijsen J, Prejbisz A, van der Wilt GJ, Deinum J; SPARTACUS investigators Quality of life in primary aldosteronism: a comparative effectiveness study of adrenalectomy and medical treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018; 103:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Almarzooqi MK, Chagnon M, Soulez G, Giroux MF, Gilbert P, Oliva VL, Perreault P, Bouchard L, Bourdeau I, Lacroix A, Therasse E. Adrenal vein sampling in primary aldosteronism: concordance of simultaneous vs sequential sampling. Eur J Endocrinol 2017; 176:159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McCormack JP, Holmes DT.. AYour results may vary: the imprecision of medical measurements. BMJ 2020; 368:m149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fraser CG Reference change values. Clin Chem Lab Med 2011; 50:807–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.