Abstract

Background

Primary cardiac sarcomas are very rare and the prognosis is poor both because the diagnosis is typically made at an advanced stage of the disease and because data are insufficient to identify a standard treatment. Surgical resection is the cornerstone of therapy with the need to develop new therapeutic strategies.

Case summary

We present a case of a young man admitted to the emergency department due to worsening dyspnoea. A left-sided sarcoma was diagnosed and treated with surgery, chemo- and radiation therapy, and subsequently with heart transplant for local recurrence of the disease. Endomyocardial biopsy made during the routine follow-up period was complicated by pericardial tamponade and cardiogenic shock and the patient was managed with veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, until recovery of left ventricular function (left ventricular ejection fraction of 55%). After 1 year a kidney transplant was performed. After 42 months from diagnosis, the patient is in good general condition.

Discussion

Primary cardiac sarcomas are treated with surgery to reach R0 (free resection margins) and with chemo- and radiation therapy with adjuvant purposes. Auto-transplantation is also performed, while conventional heart transplant must be customized on an individual basis, after excluding metastases. A multidisciplinary assessment should be performed and the single patient treated with a personalized approach, in relation to his performance status, location of the mass, and stage of the disease.

Keywords: Primary cardiac sarcoma, Heart transplant, Case report

Learning points

Primary cardiac sarcomas are very rare and the prognosis is still poor.

The differential diagnosis of cardiac masses requires a multiparametric approach (echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance and computed tomography), and it therefore represents a challenge in clinical practice.

Therapeutic approach to cardiac sarcoma has not changed over recent decades and surgical resection remains the cornerstone of the therapy, while chemotherapy and radiation therapy are usually performed with adjuvant purposes. Auto-transplantation and conventional heart transplant are reserved for specific patients.

Introduction

Primary cardiac tumours (PCTs) are very rare (∼0.02% in autoptic series), while metastatic involvement of the heart is over 20 times more common.1 About 75% of PCTs are benign, whereas sarcomas account for 65% of primary malignant cardiac tumours.2

Non-randomized trials conducted over the last decades have generated insufficient data to identify an evidence-based treatment for primary cardiac sarcoma. The prognosis is still poor, with a median survival of 6–12 months, depending on the result of surgical resection, which remains the therapeutic cornerstone. Therefore, innovative and combined treatment strategies are necessary.

We present a case of symptomatic, left-sided sarcoma treated with surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy, and subsequent heart transplant.

Timeline

| Admission | Patient was admitted for worsening dyspnoea. A left atrial mass causing mitral stenosis and suspected for malignancy was detected. No metastases were present |

| Surgical excision | An incomplete surgical resection involving the cardiac sarcoma, infiltrating the atrial wall, was performed. Radiation and chemotherapy were used with adjuvant purpose |

| 12 months from diagnosis | A heart transplant was performed for local recurrence of the disease. Subsequently an endomyocardial biopsy was performed, complicated by cardiac tamponade and cardiogenic shock, requiring surgical drainage and veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. End-stage kidney failure developed |

| 34 months from diagnosis | Kidney transplant from living donor was performed |

| 42 months from diagnosis | Patient’s current general condition is good |

Case presentation

A 39-year-old man presented to the emergency department for worsening dyspnoea for 10 days. He had suffered from asthenia and progressive exercise intolerance for 6 months. Past medical history was unremarkable.

Physical examination on admission revealed a heart rate of 70 beats/min, blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg and oxygen saturation of 97% in ambient air. Heart sounds were audible with a mitral diastolic murmur and jugular veins were not distended. The respiratory sound was decreased throughout both lung fields without rales. Peripheral oedema was not present. Electrocardiography was normal.

An echocardiographic scan showed a large non-homogeneous left atrial mass (36 mm × 21 mm diameter), adherent to the mitral ring, and involving also the left ventricle, causing severe mitral stenosis (Figure 1; Video 1). A mild pericardial effusion was also present. A gadolinium-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) confirmed the localization of the solid mass, which was isointense in T1-weighted and hyperintense in T2-weighted sequences with a non-homogeneous and mainly peripheral impregnation. The mass was heterogeneously enhanced in late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and hypoperfused in first-pass perfusion (FPP) (Figures 2A–D and 3; Videos 2 and 3).

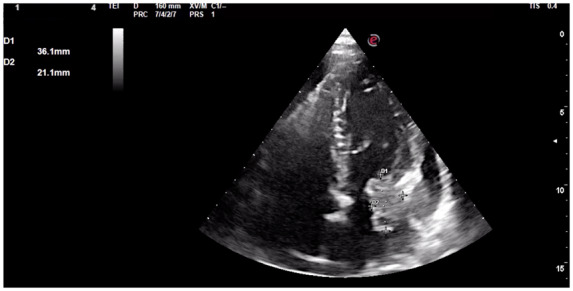

Figure 1.

Admission echocardiography showing the apical-four-chamber view of the left ventricle with inhomogeneous left atrial mass (36 mm × 21 mm diameter), adherent to the mitral ring and with irregular borders, suspected for malignancy.

Figure 2.

Tissue characterization of the cardiac mass by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. The first image (A) demonstrates a tumour (arrow) in the left atrium involving the mitral ring. The mass shows irregular borders and invades the myocardial wall and the pericardial space. It appears isointense in T1-weighted (B), hyperintense in T2-weighted (C) and heterogeneously enhanced in late gadolinium enhancement (D) images, in accordance with its heterogeneous nature (spindle cells and chondrosarcoma elements).

Figure 3.

First-pass perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance images showing hypoperfusion of the cardiac mass.

The invasive nature of the cardiac mass, the irregular margins, the presence of pericardial effusion and the LGE on CMR aroused the suspicion of malignancy. Metastases and invasion of epicardial vessels were excluded by a total-body computed tomography (CT) scan, which confirmed the large irregular mass, hypodense after contrast (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Computed tomography scan showing the large solid mass, adherent to the mitral ring, and involving the ventricular cavity.

After a multidisciplinary assessment, the cardiac surgical removal of the mass was planned.

The surgical resection of the mass was incomplete, as found during operation, due to parietal infiltration. Macroscopically, the tumour had a scirrhous consistency and a diameter of about 5 cm. The histologic examination showed a high-grade sarcoma with spindle cells and chondrosarcoma elements.

There were no intraoperative or post-operative complications and the patient was transferred to a cardiac rehabilitation program 2 weeks after surgery. Then, he received adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy. Each cycle of chemotherapy (two cycles were performed) consisted of Doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 and Ifosfamide 3000 mg/m2, on Days 1–2–3.

Twelve months after surgery and 3 months after the end of chemo- and radiation therapy, the patient had a local recurrence with severe mitral regurgitation and pulmonary hypertension, which seemed to be of post-capillary origin, as indicated by low pulmonary vascular resistance and high pulmonary artery wedge pressure at right cardiac catheterization. No metastases were present and, after a multidisciplinary evaluation, he was referred to a Cardiac Transplant Centre and treated with a conventional orthotopic heart transplant. According to the post-transplant protocol, an endomyocardial biopsy was performed, but the procedure was complicated by haemopericardium with tamponade and cardiogenic shock: the patient was immediately treated with surgical drainage, but veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (V-A ECMO) was necessary to support the cardiac function with bridge-to-recovery purpose. Subsequently, the cardiac function recovered (left ventricular ejection fraction of 55%), but irreversible end-stage renal failure developed and haemodialysis was started. After 22 months, the patient received a kidney transplant from a living donor (patient’s father).

After 7 months from the renal transplant, 30 months from the cardiac transplant and 42 months from the cardiac sarcoma diagnosis, the patient is in good general condition. Cyclosporine, Mycophenolate Mofetil, Methylprednisolone, Valganciclovir and Cotrimoxazole are maintenance therapy.

Discussion

Primary cardiac tumours are very rare, encountered in ∼0.02% of autoptic series, with an incidence of 1.38 new cases/100 000 individuals per year in an Italian 14-year population study.1,3

Only 25% of PCTs are malignant. Sarcomas represent about 65% of all malignant PCTs, but cardiac sarcomas are only 0.3% of all sarcomas. Numerous registries reported that angiosarcoma is the most common histopathological type (43%), followed by leiomyosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma.2 The median age at diagnosis of cardiac sarcoma is 40–50 years.4

During the last decades, because of the rarity of this disease, knowledge about sarcomas has improved from case series and single-centre studies, as it is not possible to rely on randomized studies or multicentric registers to standardize chemo- and radiotherapy protocols. Therefore, no substantial progress has been made in the treatment of cardiac sarcomas, which still have a median survival of 6–12 months from the diagnosis, depending on the radicality of surgical excision.5,6

Symptoms of cardiac tumours are mainly due to the site of the mass, rather than to their histopathology. Systemic manifestations or flu-like symptoms may also be present.7 Many cardiac tumours remain asymptomatic for a long time and the diagnosis is usually made at advanced stages of the disease.8

The differential diagnosis of cardiac masses (malignant and benign tumours, as well as thrombus) requires a multiparametric approach. Clinical history focused on previous extra-cardiac malignancies; echocardiography to identify the mass, evaluate its mobility and haemodynamic impact; CMR, which allows better soft-tissue characterization, high resolution and multiplane images acquisition; CT, which provides morpho-structural information of the mass and coronary arteries imaging and is the method of choice when CMR is contraindicated.9–11 Large size (≥5 cm), irregular margins, pericardial effusion and invasion of the free wall and/or the adjacent structures are features of malignancy. T1- and T2-weighted imaging (T1W, T2W) do not differentiate benign and malignant masses, while first-pass perfusion (FPP) and LGE are more accurate (Table 1).9–11

Table 1.

Imaging features suggesting benign and malignant cardiac tumours [modified from Mousavi et al.9 and Kassop et al.10]

| Benign | Malignant | |

|---|---|---|

| Feature | ||

| Site/number | Small (<5 cm), single lesion | Large (≥5 cm), multiple lesions |

| Location | Left ≫ Right | Right ≫ Left |

| Morphology | Intracameral | Intramural |

| Attachment | Narrow talk, pedunculated | Broad base |

| Borders | Smooth/well defined | Irregular |

| Invasion | None | Of the free wall and adjacent structures |

| Pericardial effusion | None | May be present |

| Calcification | Rare | Large foci in osteosarcoma |

| CT enhancement | Absent/minimal | Modest/intense |

| CMR T1W-TSE | Predominantly isointense | Predominantly isointense |

| CMR T2W-TSE | Predominantly hyperintense | Predominantly hyperintense or isointense |

| First-pass perfusion | May be present | Very frequent (70%) |

| Delayed enhancement | Usually present | Very frequent (80%) |

CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CT, computed tomography; T1W-TSE, T1-weightened sequences turbo-spin-echo; T2W-TSE, T2-weightened sequences turbo-spin-echo.

Due to the frequent diagnostic delay linked to the late development of non-specific symptoms, radical excision is rarely possible, also because of adjacent vital structures.

Moreover, cardiac sarcomas have a propensity towards early metastatic dissemination (lungs, bone, soft tissue, and brain) and should be considered as a systemic disease: the chemotherapy is used for both neo-adjuvant and adjuvant purposes to increase the chances of complete resection (R0) and reduce metastatic dissemination.6 Given the rarity of primary cardiac sarcomas and the variability of their histology and location, there are no definite guidelines for treatment. The combination of Doxorubicin and Ifosfamide is the most widely adopted chemotherapy regimen.12,13 The benefits of radiation therapy are even more controversial and can cause cardiac dysfunction. Despite this, the combination of surgery, chemo- and radiation-therapy has been reported with more than twice the median survival, if compared to surgery alone.13,14

Auto-transplantation is another possible treatment strategy (the tumour is resected ex vivo after excising the heart and reconstructing cardiac structures before the re-implantation). This approach has been developed to overcome the technical difficulties associated with the resection of left heart tumours, often hard to treat surgically.15 This would facilitate complete resection (R0) and avoid the immunosuppressant therapy. Auto-transplantation can raise the survival from malignant PCTs but has about a 15% perioperative mortality.6

A conventional heart transplant can be considered an alternative final treatment in individual cases when distant metastases have been excluded. The main risk of this treatment strategy is the growth of undetected micrometastases due to immunosuppressant therapy.6,7

Our patient presented a typical history of primary cardiac sarcoma: 39-year-old man with non-specific symptoms that worsened over a few months, mimicking left heart failure. Because of infiltrating cancer, early surgery could not allow R0 resection and, despite chemo- and radiation-therapy, a local recurrence developed 12 months after the surgery. Given the patient’s good performance status, the site of the relapsing mass, and the exclusion of metastases, after a multidisciplinary evaluation, a conventional heart transplant was performed, a non-standardized therapeutic approach burdened by the risks related to immunosuppressant therapy. Mainly due to the complication of cardiogenic shock from cardiac tamponade, end-stage renal failure developed, requiring haemodialysis and a living donor kidney transplant. About 40 months after diagnosis, the patient is in good general condition, well beyond the prognosis usually reported in the literature.

Conclusions

Primary cardiac tumours are very rare and only 25% of them are malignant: sarcomas represent 65% of all malignant PCTs. Because of their rarity, knowledge about this disease and of possible therapeutic strategies comes from single-centre studies of individual case reports or limited case series.

Due to the silent progression and non-specific symptoms caused essentially by mass location, cardiac sarcomas are usually diagnosed at advanced stages. Therefore, the prognosis of primary cardiac sarcoma is very poor and worse than that of sarcoma in other anatomical districts.

The assessment of cardiac masses requires a multiparametric approach to locate the mass, characterize its tissue and evaluate its haemodynamic impact and it represents a challenge in clinical practice.

Cardiac surgery aimed at radical resection is the cornerstone of the treatment, with chemotherapy used for neo- and adjuvant purposes. Radiation therapy, a still debated issue, is usually performed after surgery. Auto-transplantation is a possible alternative approach, while conventional heart transplant is to be reserved for those patients in whom metastases have been excluded through a multidisciplinary evaluation.

Lead author biography

Valentina Andrei studied Medicine at University of Siena, where completed her Master’s degree in 2013. From 2014 to 2017, she completed the specialty in General Practice with a particular interest in cardiovascular diseases. Since 2017 she has been a Cardiology resident at University of Florence.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to ‘Fondazione A.R. Card Onlus’ for its unconditional support. We thank Dr Giulia Pontecorboli for her valuable contribution in the interpretation of CMR images.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The author/s confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including image(s) and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1. Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol 1996;77:107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oliveira GH, Al-Kindi SG, Hoimes C, Park SJ.. Characteristics and survival of malignant cardiac tumors: a 40-year analysis of >500 patients. Circulation 2015;132:2395–2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cresti A, Chiavarelli M, Glauber M, Tanganelli P, Scalese M, Cesareo F. et al. Incidence rate of primary cardiac tumors: a 14-year population study. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2016;17:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramlawi B, Leja MJ, Abu Saleh WK, Al Jabbari O, Benjamin R, Ravi V. et al. Surgical treatment of primary cardiac sarcomas: review of a single-institution experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yin K, Luo R, Wei Y, Wang F, Zhang Y, Karlson KJ et al. Survival outcomes in patients with primary cardiac sarcoma in the United States. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020;S0022-5223(20)30209. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.12.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Magarakis M, Salerno TA.. Commentary: cardiac sarcome – can we win this battle? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020;S0022-5223(20)30259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoffmeier A, Sindermann JR, Scheld HH, Martens S.. Cardiac tumors—diagnosis and surgical treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Siontis BL, Leja M, Chugh R.. Current clinical management of primary cardiac sarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2020;20:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mousavi N, Cheezum MK, Aghayev A, Padera R, Vita T, Steigner M. et al. Assessment of cardiac masses by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: histological correlation and clinical outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e007829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kassop D, Donovan MS, Cheezum MK, Nguyen BT, Gambill NB, Blankstein R. et al. Cardiac masses on cardiac CT: a review. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep 2014;7:9281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pazos-López P, Pozo E, Siqueira ME, García-Lunar I, Cham M, Jacobi A. et al. Value of CMR for the differential diagnosis of cardiac masses. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yanagawa B, Chan EY, Cusimano RJ, Reardon MJ.. Approach to surgery for cardiac tumors: primary simple, primary complex, and secondary. Cardiol Clin 2019;37:525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hendriksen BS, Stahl KA, Hollenbeak CS, Taylor MD, Vasekar MK, Drabick JJ et al. Postoperative chemotherapy and radiation improve survival following cardiac sarcoma resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;S0022-5223(19)32223. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ravi V, Reardon MJ. Commentary: Primary cardiac sarcoma—systemic disease requires systemic therapy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 20191;S0022-5223(19)32391. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blackmon SH, Patel A, Bruckner BA, Beyer EA, Rice DC, Vaporciyan AA. et al. Cardiac autotransplantation for malignant or complex primary left-heart tumors. Tex Heart Inst J 2008;35:296–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.