Abstract

Issue addressed

Noncommunicable chronic disease underlies much of the life expectancy gap experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Modifying contributing risk factors; tobacco smoking, nutrition, alcohol consumption, physical activity, social and emotional wellbeing (SNAPS) could help close this disease gap. This scoping review identified and describes SNAPS health promotion programs implemented for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia.

Methods

Databases PubMed, CINAHL, Informit (Health Collection and Indigenous Peoples Collection), Scopus, Trove and relevant websites and clearing houses were searched for eligible studies until June 2015. To meet the inclusion criteria the program had to focus on modifying one of the SNAPS risk factors and the majority of participants had to identify as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander heritage.

Results

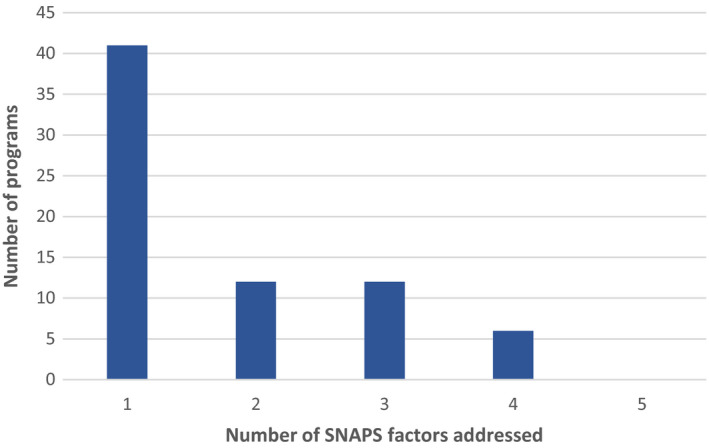

The review identified 71 health promotion programs, described in 83 publications. Programs were implemented across a range of health and community settings and included all Australian states and territories, from major cities to remote communities. The SNAPS factor addressed most commonly was nutrition. Some programs included the whole community, or had multiple key audiences, whilst others focused solely on one subgroup of the population such as chronic disease patients, pregnant women or youth. Fourteen of the programs reported no outcome assessments.

Conclusions

Health promotion programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have not been adequately evaluated. The majority of programs focused on the development of individual skills and changing personal behaviours without addressing the other health promotion action areas, such as creating supportive environments or reorienting health care services.

So What?

This scoping review provides a summary of the health promotion programs that have been delivered in Australia for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to prevent or manage chronic disease. These programs, although many are limited in quality, should be used to inform future programs. To improve evidence‐based health promotion practice, health promotion initiatives need to be evaluated and the findings published publicly.

1. BACKGROUND

The life expectancy gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non‐Indigenous Australians is approximately a decade. 1 A significant contributor to the gap is the higher burden of chronic disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities; much of which is deemed preventable. 1 The five leading risk factors associated with noncommunicable chronic diseases are tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and social and emotional wellbeing, 2 (collectively simplified by the acronym SNAPS). While there is a recognised need for urgent action to address these risk factors for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, 3 the financial and human resource supports required are currently inadequate. 4

Behavioural risk factors (also referred to as lifestyle risk factors) that contribute to preventable chronic disease have proven to be difficult to modify. 5 There are a variety of health promotion/ behaviour change theories such as the health belief, stages of change and trans‐theoretical models that consider the complexities of behaviour change and that offer “intervention” strategies. 6 Behaviour change theories highlight the role of social influences as well as the importance of the perceived outcomes and the influence of perceptions of control over said behaviours. 7 The ability to change is further complicated by the environment within which individuals live. Changing complex behaviours such as tobacco smoking, dietary intake, physical activity and alcohol consumption require a coordinated and concerted health promotion effort. 8 Acknowledging this complexity, the Ottawa Charter identifies five action areas for comprehensive health promotion: building healthy public policy, creating supportive environments, strengthening community action, developing personal skills and reorienting health care services towards prevention of illness and promotion of health. 9

Historical, cultural, socio‐economic and political dimensions play an important role in determining the health status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, their families and the communities in which they live. The difficulty of affecting behavioural risk factors for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is further challenged by factors directly and indirectly linked to colonisation and past and ongoing policies of assimilation such as intergenerational stress, social disadvantage, racism, low self‐efficacy and low income. 10 Health promotion programs that are developed specifically or primarily for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and consider historical, cultural, socio‐economic and political dimensions could contribute to a much greater reduction in the burden of disease and thus life expectancy gap. 11

Whilst health promotion activity is a core activity of comprehensive primary health care (PHC), it often extends beyond the reach and capacity of PHC services as it by necessity includes public policy, food pricing and marketing/advertising programs. However, the role of PHC services is vital as they are best placed to influence individuals and families through knowledge exchange and motivation to change behaviours within an individual's control. They can also advocate on behalf of their communities to effect change more broadly 12 and work collaboratively with other key stakeholders. Thus, PHC services are essential contributors for the delivery of health promotion programs, particularly in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, because of their in‐depth knowledge of their local community and the cultural and socio‐economic aspects impacting on health behaviours. 13 The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013‐2023 focuses on building the health promotion capacity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals in the PHC workforce as this is vital to help to ensure improved health and wellbeing in Aboriginal people. 13

Through wide consultation with the Aboriginal health sector the National Health and Medical Research Council funded Centre for Research Excellence in Aboriginal Chronic Disease Knowledge Translation and Exchange (CREATE) identified research priorities to inform practice and policy in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health sector to ultimately improve health and wellbeing. Health promotion was identified as a key topic for evidence synthesis to inform the Aboriginal Health sector. 14 The CREATE leadership group, which consisted of the chief investigators and representative from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health sector, the majority of whom identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, were actively engaged in determining the scope of this review and provided input into the interpretation of the findings and the manuscript. This scoping review aimed to identify and describe health promotion programs implemented primarily for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that focused on modifying the SNAPS risk factors (specifically to reduce smoking and alcohol consumption, increase physical activity and improve nutrition and social and emotional wellbeing) across a diverse range of health and community settings. The review also included programs designed to prevent or improve the management of noncommunicable disease through nonpharmaceutical means (specifically obesity, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It adhered to recognised methodology for the conduct of a scoping review. 15

2. METHODS

2.1. Inclusion criteria

2.1.1. Participants

Studies were included if the participants were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples living in Australia. Studies that included participants of other ethnicities living in Australia were considered if more than 50% of participants were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples. Eligible studies included participants of any age or morbidity status.

2.1.2. Concept

To be included, health promotion activities and programs must have aimed to prevent or manage chronic disease by modifying one or more of the following SNAPS behavioural risk factors; tobacco smoking, nutrition, alcohol consumption or physical activity and social and emotional wellbeing. Programs also had to be delivered to individuals and/or groups by appropriately trained staff. Unlike smoking, nutrition and alcohol, a decision was made that physical activity brief intervention, or discussion about physical activity would not be included; a program had to include an actual movement activity.

Health promotion policies, such as healthy catering policies, no smoking policies, environmental policies or urban design modification were not included, nor were activities that were limited to the provision of information in the form of posters, brochures, online websites or smartphone applications if they did not include personal contact (including telehealth or video link) with appropriately trained staff supporting the health promotion activities/advice. Health promotion activities that utilised only pharmaceutical interventions, such as nicotine replacement therapy, in isolation from other interventions, such as counselling, were also excluded as were programs for the management of asthma and mental illnesses other than depression.

2.1.3. Context

Health promotion activities and programs delivered in all regions (urban, rural and remote) and any setting (PHC centres, schools, workplaces or community centres) were included with the exception of programs implemented in a live‐in facility, such as alcohol or drug rehabilitation or a facility for diagnosed mental illness, which were not included.

2.1.4. Types of studies

All qualitative, quantitative, economic and mixed methods studies were considered for inclusion. Policy papers and expert opinion were not included. Systematic reviews or literature reviews were also excluded.

3. SEARCH STRATEGY

The search strategy aimed to identify published studies indexed in commercial databases and studies only available in the grey literature. An initial search of PubMed was completed to establish and finalise search terms. A second, database‐specific search using all identified keywords and index terms modified to fit each database was then undertaken in PubMed, CINAHL, Informit (Health Collection and Indigenous Peoples Collection), Scopus and Trove databases. The search in Trove was limited to theses only as other publication types were captured in the remaining databases. The search strategies for each database can be obtained from the corresponding author. To provide a complete scope and capture all available studies no date limitation was applied. The search was completed in June 2015.

To ensure comprehensiveness of the search strategy, the following websites and clearing houses that provide information, links and resources related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health were also searched.

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

The Lowitja Institute

Australian Government Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation

Australian Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales

Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation

Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council

Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia

Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia

Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance Northern Territory; and

Central Australian Aboriginal Congress.

The reference list of included manuscripts was also checked for additional eligible papers.

3.1. Study selection

Citations retrieved from database searching were downloaded into Endnote X7 software (Clarivate Analytics, USA) and titles and abstracts were screened and assessed for eligibility against the inclusion criteria (KC, EA, CT and CL). If deemed potentially eligible, full text of the articles were retrieved for detailed assessment. Determination of final eligibility was undertaken by KJC, CD and EA; any disagreements were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

4. DATA EXTRACTION

Data from each study were extracted with the assistance of a data extraction tool. 15 Data extracted included; author(s), year of publication, aims/objectives, program setting, participants' inclusion criteria (age, gender, ethnicity), SNAPS risk factors addressed, a brief description of the program and the key outcomes reported. The geographical classification of the program setting was determined using the Australian Standard Geographical Classification System (ASGC), 16 which since 2011 has been the geographical framework used by the Australia Bureau of Statistics (Box 1). 17 The health promotion action areas in the publication were also captured. Where multiple publications were located for one study or program, all available data were used to complete the extracted details.

BOX 1. ASGC system remoteness area (RA) classifications.

| RA1 | Major Cities |

| RA2 | Inner Regional Australia |

| RA3 | Outer Regional Australia |

| RA4 | Remote Australia |

| RA5 | Very Remote Australia |

| RA6 | Migratory |

5. RESULTS

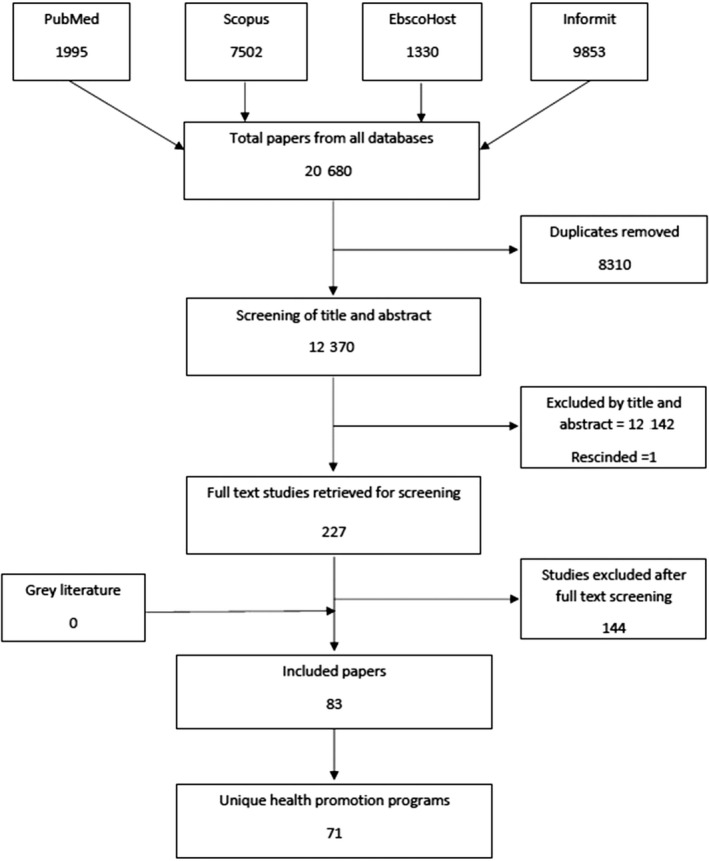

This scoping review located 83 published articles 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 that met our inclusion criteria from which we identified 71 unique health promotion programs (Figure 1). The extensive search of websites yielded no additional papers that met our inclusion criteria. The earliest paper that met the inclusion criteria was published in 1987, 47 with only 12 articles published before 2000. 22 , 32 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 50 , 52 , 56 , 57 , 73 , 86

Figure 1.

Flow diagram detailing results of literature search and study inclusion

The programs that met the inclusion criteria have been displayed across five tables (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5), one for each of the SNAPS risk factors. Programs that focused on more than one of the SNAPS risk factors are displayed in all relevant tables. The tables offer some basic information about the programs including the name of the program (if applicable), the reference(s) associated with the program, the setting in which the program was run, including, where possible, the geographical classification of the location, a description of the participants included in the program, the SNAPS risk factor(s) that were of focus, an indication if an outcome was assessed and reported and a brief description of the program.

Table 1.

Smoking – Programs that included a tobacco smoking prevention and/or cessation component

|

Program name or publication title References |

Setting | Participants | S | N | A | P | So | Outcomes assessed? | Program brief |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

“Smokin' No Way”, “SmokeCheck”, “Smoke Rings” Programs 26 (Campbell, Bohanna et al 2014) |

RA 4 and 5 – QLD Community, PHC and School Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community members, school children and smokers trying to quit. | ✓ | ✓ | A multilayered intervention: event support program, training for health workers, group support program for individuals trying to quit, lesson plans for teachers and school staff, policy guide for organisations to address smoking and monitoring of compliance with legislation on tobacco sales. | ||||

|

An intensive smoking cessation intervention for pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females on smoking rates at 36 wks' gestation 40 (Eades, Sanson‐Fisher et al 2012) |

RA 1– QLD and WA PHC Setting |

Pregnant females, aged 16 y and older, who were current smokers or recent quitters. | ✓ | ✓ | Pregnant females were assisted by their GP's to quit through a number of techniques including engaging their partner. Nicotine replacement therapy was offered after two failed quit attempts. | ||||

|

“Be Smoke Free” 50 (Gamarania, Malpraburr et al 1998) |

RA 5 – NT Community and School Settings |

Primary and high School children in remote NT communities (non‐Indigenous students were excluded from the analysis). | ✓ | ✓ | A 2‐wk educational smoking intervention involving pre‐ and postintervention questionnaires about current practices and knowledge and attitudes to smoking. | ||||

|

Multicomponent, community‐based tobacco interventions in remote Aboriginal communities 55 (Ivers, Castro et al 2006) |

RA 5 – NT Community and School Settings |

Community members and school children | ✓ | ✓ | There were a number of components to this program including health promotion activities, community and school tobacco education session and community events. | ||||

|

The Koori Tobacco Cessation Project 63 (Mark, McLeod et al 2004) |

RA 1 and 2 – NSW Community Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who smoke | ✓ | ✓ | A combination of smoking cessation group sessions and a subsidised course of nicotine replacement therapy. | ||||

|

Be Our Ally Beat Smoking Program 64 , 65 , 66 (Marley, Atkinson et al 2012, Marley, Atkinson et al 2014, Marley, Kitaura et al 2014) |

RA 4 and 5 – WA Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander current smokers 16 y+ who wish to quit or cut down or who have quit within 2 wks of enrolling | ✓ | ✓ | Tailored smoking cessation counselling during face‐to‐face visits which were held weekly for the first four weeks, monthly to 6 mo and two monthly to 12 mo. | ||||

|

Adult health checks for Indigenous Australians: the first years' experience from the Inala Indigenous Health Service 89 (Spurling, Hayman et al 2009) |

RA 1 – QLD PHC Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adults | ✓ | ✓ | Health checks undertaken in conjunction with lifestyle and health advice. About 95% of current smokers received brief smoking cessation advice and 67% received “lifestyle” advice. | ||||

|

Healthy Food Awareness Program 107 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 2 – NSW PHC Setting |

Individuals with Chronic Disease | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A one day a week session focused on diet and exercise and other health‐related issues, including smoking at the AMS and at the AMS's outreach clinics. | |||

|

Healthy Lifestyles Project 30 (Cargo, Marks et al 2011) |

RA 5 – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal Community in North East Arnhem Land | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Community health screening, feedback and discussion. Coordinated community‐directed approach to increase the allocation of community resources to prevention activities. Multiple intervention strategies implemented; family food garden, community market, new school canteen and a 4‐day healthy lifestyle festival. | ||

|

“Step up to health” –Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC) Rehabilitation Program 35 (Davey, Moore et al 2014) |

RA 2 – TAS PHC Setting, Private Physiotherapy Practice and outdoors |

Adult Aboriginal people diagnosed with COPD, IHD, or CHF and people with at least two risk factors for developing CVD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Two 1‐h supervised exercise sessions and one, 1‐h educational session per week for 8 wks. Sessions promoted self‐management approaches, cardiovascular and respiratory health, benefits of exercise, shopping, cooking and eating healthy food, medication, stress and psychological wellbeing, and smoking cessation. | |

|

Heart Health – For Our People By Our People 37 , 38 (Dimer, Jones et al 2010, Dimer, Dowling et al 2013) |

RA 1 – WA PHC Setting |

Patients with CVD or at high risk of CVD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A cardiovascular disease (CVD) management program involving assessment and reassessment, provision of health information and an individualised program including motivational and education sessions; diet and nutrition; risk factor modification (including smoking cessation); managing stress and emotion (with referral for counselling when indicated); benefits of physical activity; diabetes management and medication usage. | ||

|

Strong Women, Strong Babies, Strong Culture Program 36 , 44 , 45 , 60 (d'Espaignet, Measey et al 2003, Fejo 1994, Fejo and Rae 1996, Mackerras 2001) |

Multiple communities – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Pregnant Women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Women within Aboriginal communities help other Aboriginal women prepare for pregnancy by working together with nutritionists, community‐based health workers, local schools and other women in the community. | |

|

Waminda's Wellbeing Program 46 (Firth, Crook et al 2012) |

RA 2 – NSW Community Setting |

Predominately Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, including non‐Indigenous women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pilot program that evolved into intensive programs. Multiple components: exercise sessions; community gardens; cooking healthy meals; smoking cessation; health and wellbeing camps. | |

|

Karalundi Peer Support and Skills Training Program 52 (Gray, Sputore et al 1998) |

RA 5 – WA School Setting |

Primary, high school and TAFE students aged 10‐20 y. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ten programs aimed at: developing students' interpersonal, problem solving and decision‐making skills; quit smoking; drug; alcohol and petrol sniffing education; sex education, arts and crafts, general health promotion; eye, ear and nose care and the use of natural medicines. | ||

|

National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Prevention Strategy –‐ Reducing Alcohol and Tobacco Consumption in Pregnancy 53 (Hayward, Scrine et al 2008) |

RA 1 – QLD Community and PHC Settings |

Pregnant women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Community to inform about the dangers of Foetal Alcohol Syndrome. The program also included a resource kit for health to integrate brief interventions for smoking and alcohol use into their clinical practice. | |||

|

Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service 54 (Homer, Foureur et al 2012) |

RA 1 – NSW PHC Setting |

Pregnant Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women and non‐Indigenous women having an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander baby | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A unique model of antenatal care that addresses stress, smoking and alcohol consumption in pregnancy along with other care. | ||

|

Deadly Choices Program 61 , 62 (Malseed, Nelson et al 2014, Malseed, Nelson et al 2014) |

RA 1 – QLD School Setting |

High school students Grade 7‐12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Seven‐week physical activity and education program. Education components included leadership, chronic disease, physical activity, nutrition, smoking, harmful substances and health services. Health checks were also facilitated. | |

|

Getting Better at Chronic Care 70 (McDermott, Schmidt et al 2015) |

RA 5–‐ QLD PHC Setting |

Clients with diabetes and one major comorbidity, aged 18 y or more, poor glycaemic control and receiving regular care from the identified health service | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A self‐management program supporting patients in making and keeping appointments, understanding medications and nutrition and the effects of smoking. | |||

|

The Chronic Disease Self‐Management Project 75 (Mobbs, Nguyen et al 2003) |

RA5 –‐ NT Community and PHC Settings |

Patients previously diagnosed with diabetes and/or hypertension with or without renal involvement | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Self‐care program to develop skills including changing behaviour; smoking, nutrition, physical activity and weight loss. Building family and community healthy lifestyle infrastructure using community empowerment framework. Production of local resources (booklets and videos) including HP messages. Establishment of women's healthy weight groups, walking groups and tobacco action initiative. | |

|

The Looma Diabetes Program and Looma Healthy Lifestyle Project 33 , 84 (Clapham, O’Dea et al 2007, Rowley, Daniel et al 2000) |

RA5–‐ WA Community Setting |

Initially Aboriginal people with diabetes or at high risk, progressing to the whole community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Following community wide diabetes screening, multiple strategies were implemented progressively over several years starting with a nutrition and exercise program for diabetes and high‐risk patients progressing to range of community wide initiatives. | ||

|

Wadja Warriors Healthy Weight Program and the Injury Protection Project 88 (Smith 2002) |

RA 4 – QLD Community Setting |

Men from the local football team and other interested men in community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Injury Prevention Project to reduce on and off field violence including family violence and alcohol and drug use to reduce a major cause of injury: broken glass. Program developed to include a lifestyle program promoting good nutrition and physical activity and teaching skills that are required for making healthy changes. | |

|

WuChopperen Drug Alcohol and Other Substances program 0101 (Strempel and Drugs 2004) |

RA 1‐3 – QLD Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Provides counselling and support for young people in areas of physical, social and emotional health, and coordinates and delivers alcohol and other drug education to staff and health facilitators. | ||

|

The COACH (Coaching patients On Achieving Cardiovascular Health) program (TCP) 87 , 98 , 99 (Ski, Vale et al 2015, Vale, Jelinek et al 2003, Vale, Jelinek et al 2002.) |

Multiple RA zones QLD Telephone and postal |

Patients with Chronic Disease (CD) or at high risk of CD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A standardised coaching program delivered by registered nurses targeting CD patients and those at risk of CD, delivered by telephone and mail‐out. Coaches educate, advise and encourage patients to close the “treatment gaps” and achieve guideline‐recommended risk factor targets whilst working with their usual doctor(s). |

Abbreviations: A, alcohol; AMS, Aboriginal Medical Service; CD, chronic disease; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive heart failure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; GP, General Practitioner; HP, health promotion; IHD ischaemic heart disease; N, nutrition; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; P, physical activity; PHC, Primary Health Care; QLD, Queensland; RA, remote area; S, smoking; So, social and emotional wellbeing; TAFE, Technical and Further Education; TAS, Tasmania; WA, Western Australia.

Table 2.

Nutrition – Programs that included a nutrition component

|

Program name or publication title References |

Setting | Participants | S | N | A | P | So | Outcomes assessed? | Program brief |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diabetes Cooking Course 18 (Abbott, Davison et al 2012) |

RA 1–‐ NSW PHC Setting |

Adult Aboriginal Australians | ✓ | ✓ | Eighteen weekly cooking classes of 4 h duration to promote healthy eating on a budget. | ||||

|

Healthy Lifestyle and Weight Management Program 0105 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 1–‐ NSW PHC Setting |

Aboriginal clients of Awabakal AMS, with a focus on overweight clients or those suffering hypertension | ✓ | ✓ | Nutrition education activities and health screenings over a 6‐wk period to improve nutrition knowledge and food choice. | ||||

|

Fruit and Vegetable Program and Market Garden 0108 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 2 – NSW School Setting |

School students and health centre clients on Centrelink benefits who agree to regular health checks |

✓ | Market garden built in the school which provided fresh fruit and vegetables to students. Students also learnt about gardening and preparing healthy meals. Garden also provided subsidised fruit and vegetable boxes for eligible clients of the health service. | |||||

|

Community Kitchens 110 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 3 – NSW Setting not identified |

Aboriginal women | ✓ | Nutrition education program. One 3‐h sessions held every week for 3 mo. | |||||

|

Community Kitchen 0106 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 1 – NSW PHC Settings |

Community members | ✓ | Weekly 3‐h sessions held at AMS including nutrition education and food preparation skills. Participants plan meals, cook and share the food they have prepared. Facilitated by a Community Nutritionist and Health Promotion Officer. | |||||

|

Need for Feed Program 21 (Aliakbari, Latimore et al 2013) |

RA 4 and 5 – Qld PHC and School Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescents | ✓ | ✓ | Hands on, innovative cooking and nutrition program for adolescents. Including 20 h of tuition focusing on knife skills, nutrition, label reading, food budgeting and meal planning | ||||

|

Flinders Model of Self‐Management Support 23 (Battersby, Ah Kit et al 2008) |

RA 4 and 5 ‐ SA Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal people with type 2 diabetes aged 40 y+ | ✓ | ✓ | Aboriginal patients with diabetes interviewed by Aboriginal Health Workers to develop care plans. General practitioner and other current care providers are also involved in providing self‐management education and identifying goals in relation to weight, nutrition and exercise. | ||||

|

The Fruit and Vegetable Subsidy Program 24 , 25 (Black, Vally et al 2013, Black, Vally et al 2014) |

RA 2 and 3 ‐ NSW Community Setting |

Aboriginal children and their families | ✓ | ✓ | The provision of heavily subsidised fruit and vegetable boxes to children and their families. These boxes were accompanied by nutrition and dietary education sessions provided by dietitians or trained nutrition health workers. | ||||

|

The Healthy Lifestyle Programme (HELP) 31 (Chan, Ware et al 2007) |

RA 1 and 4 – QLD Community Setting |

Adult Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people over 20 y of age with either type 2 diabetes and/or overweight | ✓ | ✓ | Series of educational workshops on nutrition and exercise. Participants were encouraged to self‐monitor their physical activity through the use of pedometers. Participants with type 2 diabetes were also encouraged to monitor fasting plasma glucose. | ||||

|

Nutrition: at the heart of good health 0102 (Fitzpatrick and Australians for Native Title Reconciliation 2007) |

RA 5 – WA Community Setting |

Aboriginal children and their mothers | ✓ | Drop‐in centre providing healthy meals and nutrition education. Cooking classes and nutrition education for women. | |||||

|

Good food, great kids: An Indigenous Community Nutrition Project 0103 (Fitzpatrick and Australians for Native Title Reconciliation 2007) |

RA 2 –‐ VIC Community and School Setting |

Aboriginal community members, in particular school children and women | ✓ | Multiple components including school gardens, healthy food policies in school and school cooking program. Nutrition and cooking program for women and a community garden. | |||||

|

Pathways to Prevention Project – Practical Cooking Workshops 49 (Foley 2010) |

RA 1 – QLD Community Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults | ✓ | ✓ | A series of practical cooking workshops. | ||||

|

Walk‐about Together Program 59 (Longstreet, Heath et al 2008) |

RA 3 –‐ QLD Community and PHC Setting |

Overweight Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults | ✓ | ✓ | Participants received nutrition and physical activity advice and were provided a pedometer and log book. | ||||

|

Cooking Classes for Diabetes 76 , 104 (Moore, Webb et al 2006, Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 1 – NSW Community and PHC Settings |

Clients with diabetes and their families | ✓ | ✓ | Cooking classes for people with diabetes and their families including health education. | ||||

|

The Bindjareb Yorgas Health Programme 78 (Nilson, Kearing‐Salmon et al 2015) |

RA 2 – WA Community Setting |

Aboriginal Women | ✓ | ✓ | The program consisting of four health promotion components, this paper is only reporting on the cooking and nutrition classes which were run weekly during school term over a 12‐mo period. | ||||

|

Minjilang Good Food and Health Project 56 , 57 (Lee, Bailey et al 1994, Lee, Bonson et al 1995) |

RA 5 – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal community members | ✓ | ✓ | Community health screening, regular dietary intake monitoring and nutrition education including promotion of healthy foods in stores. | ||||

|

Outreach School Garden Project 100 (Viola 2006) |

RA 5 – QLD School Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students | ✓ | ✓ | This program incorporated formal nutrition and gardening education lessons into the core school curriculum through key learning areas. Healthy changes to the tuckshop menu were also made. | ||||

|

Spring into Shape Program 0109 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 2 – NSW PHC Setting |

Not specified | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Exercise and nutrition program to promote healthy lifestyle change and manage stress in a better way. Wide range of physical activities occur with nutrition education sessions. Fruit and vegetable box provided for the cost of $5 including recipes. | |||

|

Healthy Lifestyle Program 111 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 3 – NSW Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal adults | ✓ | ✓ | Weekly meeting with a weigh‐in and talks on topics such as healthy eating, physical activity and meal preparation. Program also includes exercise sessions and a 30‐min group walk. Sessions supported by Weight Watchers. | ||||

|

Building Healthy Communities Project 112 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 4 – NSW PHC Setting |

Aboriginal community members including children | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Multiple components. Nutrition and cooking classes through “Quick Meals for Kooris” program. Community vegetable garden was established, the walking track was upgraded and a range of physical activity sessions. Women's self‐ esteem classes, craft and jewellery making classes were also part of the project. |

|||

|

Healthy Food Awareness Program 107 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 2 – NSW PHC Setting |

Individuals with Chronic Disease | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A one day a week session focused on diet and exercise and other health‐related issues, including smoking at the AMS and at the AMS's outreach clinics. | |||

|

The Chronic Disease Self‐Management pilot study 20 (Ah Kit, Prideaux et al 2003) |

RA 4 and 5 – SA Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal people with type 2 diabetes. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A chronic disease self‐management model for Aboriginal people consisting of local support coordination, extension of preventive health programs, self‐management processes and tools to suit goal setting and behaviour change including group exercise and diet education sessions and appropriate staff training. | |||

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women's Fitness Program 27 , 28 , 29 (Canuto, McDermott et al 2011, Canuto, Cargo et al 2012, Canuto, Spagnoletti et al 2013) |

RA 1 – SA Community Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women 18‐64 y with waist circumference greater than 80cm | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Twelve‐week program including two 60‐min group exercise classes per week, and four nutrition education workshops. RCT vs waitlisted controls. | |||

|

Healthy Lifestyles Project 30 (Cargo, Marks et al 2011) |

RA 5 – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Community members | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Community health screening, feedback and discussion. Coordinated community‐directed approach to increase the allocation of community resources to prevention activities. Multiple intervention strategies implemented; family food garden, community market, new school canteen and a 4‐day healthy lifestyle festival. | ||

|

Aunty Jean's Good Health Program 34 (Curtis, Service et al 2004) |

RA 3 – NSW Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal Elders | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Twelve‐week program involving weekly group sessions that included a medical check, group exercise and information sharing from health professionals across multiple topics (nutrition and cooking, exercise, diabetes and stress management). This was combined with a self‐managed, self‐directed home program. | |||

|

“Step up to health” ‐Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC) Rehabilitation Program 35 (Davey, Moore et al 2014) |

RA 2 –TAS PHC Setting, Private Physiotherapy Practice and outdoors |

Adult Aboriginal people diagnosed with COPD, IHD or CHF and people with at least two risk factors for developing CVD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Two 1‐h supervised exercise sessions and one, 1‐h educational session per week for 8 wks. Sessions promoted self‐management approaches, cardiovascular and respiratory health, benefits of exercise, shopping, cooking and eating healthy food, medication, stress and psychological wellbeing and smoking cessation. | |

|

Heart Health – For Our People By Our People 37 , 38 (Dimer, Jones et al 2010, Dimer, Dowling et al 2013) |

RA 1 – WA PHC Setting |

Patients with CVD or at high risk of CVD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A cardiovascular disease (CVD) management program involving assessment and reassessment, provision of health information and an individualised program including motivational and education sessions; diet and nutrition; risk factor modification (including smoking cessation); managing stress and emotion (with referral for counselling when indicated); benefits of physical activity; diabetes management and medication usage. | ||

|

Birth to Elders Nutrition Program 41 , 42 (Edwards 2004, Edwards 2005) |

RA 3 and 5 – SA Community, Child Care Centres, PHC and School Settings |

Aboriginal community members | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple community‐based social and emotional wellbeing activities, providing health paraphernalia to communities, including nutritional education and physical health interventions such as indoor little athletics and sports events. | ||

|

Gut Busters 43 (Egger, Fisher et al 1999) |

RA 5 –‐ QLD Community Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Program run on four remote islands targeting four major lifestyle risk factors; reducing fat intake; increasing dietary fibre; increasing daily movement and changing “obesogenic” habits. The program encourages long‐term lifestyle changes including moderate use of alcohol and moderate‐intensity accumulated activity. Regular planned walking groups occurred on two islands. | ||

|

Strong Women, Strong Babies, Strong Culture Program 36 , 44 , 45 , 60 (d'Espaignet, Measey et al 2003, Fejo 1994, Fejo and Rae 1996, Mackerras 2001) |

Multiple communities – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Pregnant Women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Women within Aboriginal communities help other Aboriginal women prepare for pregnancy by working together with nutritionists, community‐based health workers, local schools and other women in the community. | |

|

Waminda's Wellbeing Program 46 (Firth, Crook et al 2012) |

RA 2 – NSW Community Setting |

Predominately Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, including non‐Indigenous women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pilot program that evolved into intensive programs. Multiple components: exercise sessions; community gardens; cooking healthy meals; smoking cessation; health and wellbeing camps. | |

|

Diabetes Management and Care Program 51 (Gracey, Bridge et al 2006) |

RA 5 – WA Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal community members | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple strategies including lifestyle disease education, promotion of healthy eating, exercise and active recreation program, health screening and medication compliance. | |||

|

Deadly Choices Program 61 , 62 (Malseed, Nelson et al 2014, Malseed, Nelson et al 2014) |

RA 1 – QLD School Setting |

High school students Grade 7‐12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Seven‐week physical activity and education program. Education components included leadership, chronic disease, physical activity, nutrition, smoking, harmful substances and health services. Health checks were also facilitated. | |

|

Getting Better at Chronic Care 70 (McDermott, Schmidt et al 2015) |

RA 5 – QLD PHC Setting |

Clients with diabetes and one major comorbidity, aged 18 y or more, poor glyacemic control and receiving regular care from the identified health service | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A self‐management program supporting patients in making and keeping appointments, understanding medications and nutrition and the effects of smoking. | |||

|

The Chronic Disease Self‐Management Project 75 (Mobbs, Nguyen and Bell 2003) |

RA5 – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Patients previously diagnosed with diabetes and/or hypertension with or without renal involvement | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Self‐care program to develop skills including changing behaviour; smoking, nutrition, physical activity and weight loss. Building family and community healthy lifestyle infrastructure using community empowerment framework. Production of local resources (booklets and videos) including HP messages. Establishment of women's healthy weight groups, walking groups and tobacco action initiative. | |

|

Awareness and Self‐Management Programme 81 (Payne 2013) |

RA 3 – QLD Community Setting |

Women with type 2 diabetes or identified has having an elevated risk of developing disease. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Support groups involving information sessions on self‐management strategies; grief and loss; health ownership and concepts of shared knowledge; and diet and exercise. | |||

|

A pilot study of Aboriginal health promotion from an ecological perspective 82 , 83 (Reilly, Doyle et al 2007, Reilly, Cincotta et al 2011) |

RA 2 – VIC Community Setting |

Multiple subgroups; Elders, women, junior footballers, employees, sporting club members | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple programs including; a health “summer school” for health promotion practitioners; a nutrition program for under 17‐year‐old footballers; initiatives to improve the dietary quality of food supplied at the football and netball club; a series of focus groups to adapt mainstream nutrition guidelines for the Indigenous community; a weekly self‐directed health‐focused meeting for women; and a workplace exercise program. | |||

|

The Looma Diabetes Program and Looma Healthy Lifestyle Project 33 , 84 (Clapham, O'Dea et al 2007, Rowley, Daniel et al 2000) |

RA5 – WA Community Setting |

Initially Aboriginal people with diabetes or at high risk, progressing to the whole community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Following community wide diabetes screening, multiple strategies were implemented progressively over several years starting with a nutrition and exercise program for diabetes and high‐risk patients progressing to range of community wide initiatives. | ||

|

Wadja Warriors Healthy Weight Program and the Injury Protection Project 88 (Smith 2002) |

RA 4 – QLD Community Setting |

Men from the local football team and other interested men in community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Injury Prevention Project to reduce on‐ and off‐field violence including family violence and alcohol and drug use to reduce a major cause of injury: broken glass. Program developed to include a lifestyle program promoting good nutrition and physical activity and teaching skills that are required for making healthy changes. | |

|

The COACH (Coaching patients On Achieving Cardiovascular Health) program (TCP) 87 , 98 , 99 (Ski, Vale et al 2015, Vale, Jelinek et al 2003, Vale, Jelinek et al 2002.) |

Multiple RA zones QLD Telephone and postal |

Patients with Chronic Disease (CD) or at high risk of CD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A standardised coaching program delivered by registered nurses targeting CD patients and those at risk of CD, delivered by telephone and mail‐out. Coaches educate, advise and encourage patients to close the “treatment gaps” and achieve guideline‐recommended risk factor targets whilst working with their usual doctor(s). |

Abbreviations: A, alcohol; AMS, Aboriginal Medical Service; CD, chronic disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; N, nutrition; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; P, physical activity; PHC, Primary Health Care; QLD, Queensland; RA, remote area; RCT, Randomised Controlled Trial; S, smoking; SA, South Australia; So, social and emotional wellbeing; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

Table 3.

Alcohol – Programs that included an alcohol prevention and/or management component

|

Program name or publication title References |

Setting | Participants | S | N | A | P | So | Outcomes assessed? | Program brief |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

An Alcohol Prevention Program for Aboriginal Children 22 (Barber, Walsh et al 1988) |

RA4 – Qld School Setting |

Year 7 school children | ✓ | ✓ | Community developed lesson plans which were delivered by school teachers. The program was divided in to eight lessons that focused on the misuse of alcohol and promoting healthy choices and behaviours. | ||||

|

Community Approach to Drug Abuse Prevention 47 (Fisher and van der Heide 1987) |

Community Setting | Young Aboriginal people at risk of alcohol abuse | ✓ | Aboriginal workers are assisted to develop programs specifically tailored to their communities. Activities include teaching community members about teamwork, health promotion, community development and planning for action. | |||||

|

Aboriginal Women's Group 58 (Lee, Dawson and Conigrave 2013) |

RA1 – NSW PHC and Outpatient Hospital Settings |

Aboriginal female clients of an outpatient alcohol and drug treatment service | ✓ | ✓ | A group of women who attended a drug and alcohol clinic met up to discuss support and develop personal skills. | ||||

|

Central Australian Aboriginal Alcohol Programs Unit – Grog Action Plan 73 (Miller 1995) |

Multiple RA Zones – NT Community and School Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | ✓ | ✓ | Primary, secondary and tertiary prevention and treatment programs including school‐based education programs, Men's and Women's day care program, outreach awareness programs, men's, women's and children's evening program. Local communities are also encouraged to develop their own Grog Action Plans. | ||||

|

When You Think About It 86 (Sheehan, Schonfeld et al 1995) |

RA3 – Qld School Setting |

Aboriginal High School Students | ✓ | ✓ | Educating students on what constituted responsible drinking in order to reduce drinking driving by Queensland high school students. The program consisted of six lessons accompanied by handbook guided classes with teachers. | ||||

|

The Waringarri Project 32 (Chisholm 1989) |

RA4 – WA Community and School setting |

Aboriginal community members | ✓ | ✓ | Trained staff implemented psycho‐social method of targeting individuals in crisis and using community development strategies to overcome the crisis, also established self‐help groups and introducing alcohol concepts into schools | ||||

|

Gut Busters 43 (Egger, Fisher et al 1999) |

RA5 – QLD Community Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Program run on four remote islands targeting four major lifestyle risk factors; reducing fat intake; increasing dietary fibre; increasing daily movement and changing “obesogenic” habits. The program encourages long‐term lifestyle changes including moderate use of alcohol and moderate‐intensity accumulated activity. Regular planned walking groups occurred on two islands. | ||

|

Strong Women, Strong Babies, Strong Culture Program 36 , 44 , 45 , 60 (d'Espaignet, Measey et al 2003, Fejo 1994, Fejo and Rae 1996, Mackerras 2001) |

Multiple communities ‐–NT Community and PHC Settings |

Pregnant Women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Women within Aboriginal communities help other Aboriginal women prepare for pregnancy by working together with nutritionists, community‐based health workers, local schools and other women in the community. | |

|

Karalundi Peer Support and Skills Training Program 52 (Gray, Sputore et al 1998) |

RA5 – WA School Setting |

Primary, high school and TAFE students aged 10‐20 y | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ten programs aimed at: developing students' interpersonal, problem‐solving and decision‐making skills; quit smoking; drug; alcohol and petrol sniffing education; sex education, arts and crafts, general health promotion; eye, ear and nose care and the use of natural medicines. | ||

|

National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Prevention Strategy ‐ Reducing Alcohol and Tobacco Consumption in Pregnancy 53 (Hayward, Scrine et al 2008) |

RA1 – QLD Community and PHC Settings |

Pregnant women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Community to inform about the dangers of Foetal Alcohol Syndrome. The program also included a resource kit for health to integrate brief interventions for smoking and alcohol use into their clinical practice. | |||

|

Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service 54 (Homer, Foureur et al 2012) |

RA 1 – NSW PHC Setting |

Pregnant Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women and non‐Indigenous women having an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander baby | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A unique model of antenatal care that addresses stress, smoking and alcohol consumption in pregnancy along with other care. | ||

|

Deadly Choices Program 61 , 62 (Malseed, Nelson et al 2014, Malseed, Nelson et al 2014) |

RA 1 – QLD School Setting |

High school students Grade 7‐12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Seven‐week physical activity and education program. Education components included leadership, chronic disease, physical activity, nutrition, smoking, harmful substances and health services. Health checks were also facilitated. | |

|

Watharoung Koori Youth Prevention Programs 74 (Milward 2009) |

RA1 – Vic Community Setting |

Aboriginal Youth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A variety of programs in partnership with other organisations to prevention the use of alcohol and other drugs. The programs are designed to empower youth, strengthen individual Koori identity and learn more about their culture through camps, surfing competitions and an AFL football program. | |||

|

Wadja Warriors Healthy Weight Program and the Injury Protection Project 88 (Smith 2002) |

RA 4 – QLD Community Setting |

Men from the local football team and other interested men in community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Injury Prevention Project to reduce on‐ and off‐field violence including family violence and alcohol and drug use to reduce a major cause of injury: broken glass. Program developed to include a lifestyle program promoting good nutrition and physical activity and teaching skills that are required for making healthy changes. | |

|

WuChopperen Drug Alcohol and Other Substances program 90 (Strempel and Australian National Council on Drugs 2004) |

RA 1‐3 – QLD Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Provides counselling and support for young people in areas of physical, social and emotional health, and coordinates and delivers alcohol and other drug education to staff and health facilitators. | ||

|

The COACH (Coaching patients On Achieving Cardiovascular Health) program (TCP) 87 , 98 , 99 (Ski, Vale et al 2015, Vale, Jelinek et al 2003, Vale, Jelinek et al 2002.) |

Multiple RA zones QLD Telephone and postal |

Patients with Chronic Disease (CD) or at high risk of CD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A standardised coaching program delivered by registered nurses targeting CD patients and those at risk of CD, delivered by telephone and mail‐out. Coaches educate, advise and encourage patients to close the “treatment gaps” and achieve guideline‐recommended risk factor targets whilst working with their usual doctor(s). |

Abbreviations: A, alcohol; AFL, Australian Football League; CD, chronic disease; N, nutrition; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; P, physical activity; PHC, Primary Health Care; QLD, Queensland; RA, remote area; S, smoking; So, social and emotional wellbeing; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

Table 4.

Physical activity – Programs that included a physical activity component

|

Program name or publication title References |

Setting | Participants | S | N | A | P | So | Outcomes assessed? | Program brief |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Water Aerobics Program 110 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 3 – NSW Community Setting |

Individuals with chronic disease | ✓ | ✓ | Two 1‐h water‐aerobic sessions per week for 6 wks. Includes regular monitoring of participant's measurements. | ||||

|

Koori Walkabout 106 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 1 – NSW Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal adults | ✓ | Koori Walkabout is a group walking program registered with the National Heart Foundation. Participants receive Heart Foundation information packs and a pedometer. T‐shirt incentive after seven sessions. The group walks once a week for 30‐45 min. The walk is followed by a healthy lunch at the AMS. | |||||

|

A 12‐wk sports‐based exercise program for inactive Indigenous Australian men 72 (Mendham, Duffield et al 2014) |

Regional NSW Community Setting |

Inactive Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander men with not diagnosed with no pre‐existing CVD or metabolic disorders | ✓ | ✓ | Two to three strength and cardio exercise sessions per week. | ||||

|

Our Games Our Health 80 (Parker, Meiklejohn et al 2006) |

RA 2 and 4 – QLD Community and School Settings |

The Aboriginal Community groups and school students | ✓ | ✓ | The program consisted of three interlocking stages, community engagement, community mobilisation, and community capacity building. The project aimed to focus on men and older people, however, was redirected to focus on school children. Physical activity was Indigenous games form the book Choopadoo Games from the Dreamtime. | ||||

|

Healthy Food Awareness Program 107 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 2 – NSW PHC Setting |

Individuals with Chronic Disease | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A one day a week session focused on diet and exercise and other health‐related issues, including smoking at the AMS and at the AMS's outreach clinics. | |||

|

Spring into Shape Program 109 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 2 – NSW PHC Setting |

Not specified | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Exercise and nutrition program to promote healthy lifestyle change and manage stress in a better way. Wide range of physical activities occur with nutrition education sessions. Fruit and vegetable box provided for the cost of $5 including recipes. | |||

|

Healthy Lifestyle Program 111 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 3 – NSW Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal adults | ✓ | ✓ | Weekly meeting with a weigh in and talks on topics such as healthy eating, physical activity and meal preparation. Program also includes exercise sessions and a 30‐min group walk. Sessions supported by Weight Watchers. | ||||

|

Building Healthy Communities Project 112 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 4 – NSW PHC Setting |

Aboriginal community members including children | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple components. Nutrition and cooking classes through “Quick Meals for Kooris” program. Community vegetable garden was established, the walking track was upgraded and a range of physical activity sessions. Women's self‐ esteem classes, craft and jewellery making classes were also part of the project. | |||

|

The Chronic Disease Self‐Management pilot study 20 (Ah Kit, Prideaux et al 2003) |

RA 4 and 5 – SA Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal people with type 2 diabetes. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A chronic disease self‐management model for Aboriginal people consisting of local support coordination, extension of preventive health programs, self‐management processes and tools to suit goal setting and behaviour change including group exercise and diet education sessions and appropriate staff training. | |||

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women's Fitness Program 27 , 28 , 29 (Canuto, McDermott et al 2011, Canuto, Cargo et al 2012, Canuto, Spagnoletti et al 2013) |

RA 1 – SA Community Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women 18‐64 y with waist circumference greater than 80cm | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Twelve‐week program including two 60‐min group exercise classes per week, and four nutrition education workshops. RCT vs waitlisted controls. | |||

|

Healthy Lifestyles Project 30 (Cargo, Marks et al 2011) |

RA 5 – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal Community in North East Arnhem Land | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Community health screening, feedback and discussion. Coordinated community‐directed approach to increase the allocation of community resources to prevention activities. Multiple intervention strategies implemented; family food garden, community market, new school canteen, weekly walking program and a 4‐day healthy lifestyle festival. | ||

|

Aunty Jean's Good Health Program 34 (Curtis, Service et al 2004) |

RA 3 – NSW Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal Elders | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Twelve‐week program involving weekly group sessions that included a medical check, group exercise and information sharing from health professionals across multiple topics; nutrition and cooking, exercise, diabetes and stress management. This was combined with a self‐managed, self‐directed home program. | |||

|

“Step up to health” ‐Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC) Rehabilitation Program 35 (Davey, Moore et al 2014) |

RA 2 – TAS PHC Setting, Private Physiotherapy Practice and outdoors |

Adult Aboriginal people diagnosed with COPD, IHD, or CHF and people with at least 2 risk factors for developing CVD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Two 1‐h supervised exercise sessions and one, 1‐h educational session per week for 8 wks. Sessions promoted self‐management approaches, cardiovascular and respiratory health, benefits of exercise, shopping, cooking and eating healthy food, medication, stress and psychological wellbeing, and smoking cessation. | |

|

Birth to Elders Nutrition Program 41 , 42 (Edwards 2004, Edwards 2005) |

RA 3 and 5 ‐ SA Community, Child Care Centres, PHC and School Settings |

Aboriginal community members | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple community‐based social and emotional wellbeing activities, providing health paraphernalia to communities, including nutritional education, and physical health interventions such as indoor little athletics and sports events. | ||

|

Gut Busters 43 (Egger, Fisher et al 1999) |

RA5 – QLD Community Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Program run on four remote islands targeting four major lifestyle risk factors; reducing fat intake; increasing dietary fibre; increasing daily movement and changing “obesogenic” habits. The program encourages long‐term lifestyle changes including moderate use of alcohol and moderate‐intensity accumulated activity. Regular planned walking groups occurred on two islands. | ||

|

Waminda's Wellbeing Program 46 (Firth, Crook et al 2012) |

RA2 – NSW Community Setting |

Predominately Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, including non‐Indigenous women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pilot program that evolved into intensive programs. Multiple components: exercise sessions; community gardens; cooking healthy meals; smoking cessation; health and wellbeing camps. | |

|

Diabetes Management and Care Program 51 (Gracey, Bridge et al 2006) |

RA5 – WA Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal community members | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple strategies including lifestyle disease education, promotion of healthy eating, exercise and active recreation program, health screening and medication compliance. | |||

|

Deadly Choices Program 61 , 62 (Malseed, Nelson et al 2014, Malseed, Nelson et al 2014) |

RA1 – QLD School Setting |

High school students Grade 7‐12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Seven‐week physical activity and education program. Education components included leadership, chronic disease, physical activity, nutrition, smoking, harmful substances and health services. Health checks were also facilitated. | |

|

Watharoung Koori Youth Prevention Programs 74 (Milward 2009) |

RA1 – Vic Community Setting |

Aboriginal Youth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A variety of programs in partnership with other organisations to prevention the use of alcohol and other drugs. The programs are designed to empower youth, strengthen individual Koori identity and learn more about their culture through camps, surfing competitions and an AFL football program. | |||

|

The Chronic Disease Self‐Management Project 75 (Mobbs, Nguyen et al 2003) |

RA5 – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Patients previously diagnosed with diabetes and/or hypertension with or without renal involvement | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Self‐care program to develop skills including changing behaviour; smoking, nutrition, physical activity and weight loss. Building family and community healthy lifestyle infrastructure using community empowerment framework. Production of local resources (booklets and videos) including HP messages. Establishment of women's healthy weight groups, walking groups and tobacco action initiative. | |

|

A pilot study of Aboriginal health promotion from an ecological perspective 82 , 83 (Reilly, Doyle et al 2007, Reilly, Cincotta et al 2011) |

RA2 – VIC Community Setting |

Multiple subgroups; Elders, women, junior footballers, employees, sporting club members | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple programs including; a health “summer school” for health promotion practitioners; a nutrition program for under 17‐year‐old footballers; initiatives to improve the dietary quality of food supplied at the football and netball club; a series of focus groups to adapt mainstream nutrition guidelines for the Indigenous community; a weekly self‐directed health‐focused meeting for women; and a workplace exercise program. | |||

|

The Looma Diabetes Program and Looma Healthy Lifestyle Project 33 , 84 (Clapham, O'Dea et al 2007, Rowley, Daniel et al 2000) |

RA5 – WA Community Setting |

Initially Aboriginal people with diabetes or at high risk, progressing to the whole community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Following community wide diabetes screening, multiple strategies were implemented progressively over several years starting with a nutrition and exercise program for diabetes and high‐risk patients progressing to range of community wide initiatives. | ||

|

Indigenous Surf Programs 85 (Rynne, Rossi et al 2012) |

Multiple RAs – NSW, QLD, Vic and SA Community and School Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (three sites focused on youth) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Five surfing programs across four states. Aim to foster connection to culture, identity, promote physical activity and social connection. | |||

|

Wadja Warriors Healthy Weight Program and the Injury Protection Project 88 (Smith 2002) |

RA 4 – QLD Community Setting |

Men from the local football team and other interested men in community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Injury Prevention Project to reduce on‐ and off‐field violence including family violence and alcohol and drug use to reduce a major cause of injury: broken glass. Program developed to include a lifestyle program promoting good nutrition and physical activity and teaching skills that are required for making healthy changes. |

Abbreviations: A, alcohol; AFL, Australian Football League; AMS, Aboriginal Medical Service; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive heart failure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IHD ischaemic heart disease; N, nutrition; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; P, physical activity; PHC, Primary Health Care; QLD, Queensland; RA, remote area; RCT, Randomised Controlled Trial; S, smoking; SA, South Australia; So, social and emotional wellbeing; TAS, Tasmania; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

Table 5.

Social and emotional wellbeing – Programs that included a social and emotional wellbeing component

|

Program name or publication title References |

Setting | Participants | S | N | A | P | So | Outcomes assessed? | Program brief |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aboriginal Girls Circle 39 (Dobia, Bodkin‐Andrews et al 2014) |

RA 2 – NSW School Setting |

Aboriginal girls attending secondary schools. | ✓ | ✓ | An intervention targeting social connection, participation, resilience, cultural identity and self confidence amongst Aboriginal girls attending secondary schools. | ||||

|

Yarrabah's Yaba Bimbie Men's Group and Ma'Ddaimba Balas men's group 67 , 69 (McCalman, Baird et al 2007, McCalman, Tsey et al 2010) |

RA 3 – QLD Community Setting |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men | ✓ | ✓ | Men's groups that has a multilevel empowerment framework addressing social and emotional wellbeing, linked with the Family Empowerment Program | ||||

|

The Family Wellbeing Program 68 , 71 (McEwan, Tsey et al 2009, McCalman, McEwan et al 2010) |

RA 3 – Qld and RA 4 – NT Community Setting |

Aboriginal adults from two regions | ✓ | ✓ | An educational program that builds communication, problem‐solving, conflict resolution and other necessary skills to enable individuals to take greater control and responsibility for family, work and community life. | ||||

|

Yanan Ngurra‐ngu Walalja – The Halls Creek Community Family Programme 77 (Munns 2010) |

RA 5 – WA Community Setting |

Antenatal clients and all parents with children aged 0‐3 y | ✓ | ✓ | A comprehensive home visiting strategy with a holistic focus on the family's child rearing environment, recognising psychosocial influences. This program also assisted parents to develop strategies to address their children's physical, cognitive, emotional, behavioural, educational and language development, along with general health and nutritional needs for the children and the whole family. | ||||

|

Kulintja Nganampa Maa‐kunpuntjaku (Strengthening Our Thinking) 79 (Osborne 2013) |

RA 5 – SA Community and School Settings |

School aged children | ✓ | ✓ | Mind matters social and emotional wellbeing program adapted for use in Anangu schools. | ||||

|

Voices United for Harmony 91 , 92 , 93 (Sun and Buys 2012, Sun and Buys 2013, Sun and Buys 2013) |

Unidentified communities – QLD Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults | ✓ | ✓ | Twelve‐month‐old singing program with weekly 2‐h sessions and monthly performances led by skilled experienced singing group leaders. | ||||

|

Family Wellbeing Personal Development and Empowerment Program 97 (Tsey, Whiteside et al 2005) |

RA 5 – Qld School Settings |

Indigenous school children | ✓ | ✓ | A group program that helps children develop analytical and problem‐solving skills, thereby enhancing their psychosocial development. Program delivered by three out‐reach staff (two of whom were Indigenous) over 12 1‐h sessions, every 2‐3 wks over two school terms. | ||||

|

Family Wellbeing Course 94 , 95 , 96 (Tsey 2000, Tsey and Every 2000, Tsey and Every 2001) |

RA 4 – NT Community and School Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families | ✓ | ✓ | Family Wellbeing course aims to empower participants and their families to assume a greater control over the conditions influencing their lives. It places particular emphasis on parenting and relationship skills. Four stages of the course, each runs for 10 wks with one 4‐h session per week by trained counsellors. | ||||

|

Spring into Shape Program 109 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 2 – NSW PHC Setting |

Not specified | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Exercise and nutrition program to promote healthy lifestyle change and manage stress in a better way. Wide range of physical activities occur with nutrition education sessions. Fruit and vegetable boxes provided for the cost of $5 including recipes. | |||

|

Building Healthy Communities Project 112 (Aboriginal Health Medical Research Council of New South Wales 2009) |

RA 4 – NSW PHC Setting |

Aboriginal community members including children | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple components. Nutrition and cooking classes through “Quick Meals for Kooris” program. Community vegetable garden was established, the walking track was upgraded and a range of physical activity sessions. Women's self‐ esteem classes, craft and jewellery making classes were also part of the project. | |||

|

The Waringarri Project 32 (Chisholm 1989) |

RA 4 – WA Community and School setting |

Aboriginal community members | ✓ | ✓ | Trained staff implemented psycho‐social method of targeting individuals in crisis and using community development strategies to overcome the crisis, also established self‐help groups and introducing alcohol concepts into schools | ||||

|

“Step up to health” –Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC) Rehabilitation Program 35 (Davey, Moore et al 2014) |

RA 2 –TAS PHC Setting, Private Physiotherapy Practice and outdoors |

Adult Aboriginal people diagnosed with COPD, IHD, or CHF and people with at least two risk factors for developing CVD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Two 1‐h supervised exercise sessions and one, 1‐h educational session per week for 8 wks. Sessions promoted self‐management approaches, cardiovascular and respiratory health, benefits of exercise, shopping, cooking and eating healthy food, medication, stress and psychological wel‐lbeing, and smoking cessation. | |

|

Heart Health – For Our People By Our People 37 , 38 (Dimer, Jones et al 2010, Dimer, Dowling et al 2013) |

RA 1 – WA PHC Setting |

Patients with CVD or at high risk of CVD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A cardiovascular disease (CVD) management program involving assessment and reassessment, provision of health information and an individualised program including motivational and education sessions; diet and nutrition; risk factor modification (including smoking cessation); managing stress and emotion (with referral for counselling when indicated); benefits of physical activity; diabetes management and medication usage. | ||

|

Birth to Elders Nutrition Program 41 , 42 (Edwards 2004, Edwards 2005) |

RA 3 and 5 – SA Community, Child Care Centres, PHC and School Settings |

Aboriginal community members | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple community‐based social and emotional wellbeing activities, providing health paraphernalia to communities, including nutritional education, and physical health interventions such as indoor little athletics and sports events. | ||

|

Strong Women, Strong Babies, Strong Culture Program 36 , 44 , 45 , 60 (d'Espaignet, Measey et al 2003, Fejo 1994, Fejo and Rae 1996, Mackerras 2001) |

Multiple communities – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Pregnant Women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Women within Aboriginal communities help other Aboriginal women prepare for pregnancy by working together with nutritionists, community‐based health workers, local schools and other women in the community. | |

|

Waminda's Wellbeing Program 46 (Firth, Crook et al 2012) |

RA2 – NSW Community Setting |

Predominately Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, including non‐Indigenous women | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pilot program that evolved into intensive programs. Multiple components: exercise sessions; community gardens; cooking healthy meals; smoking cessation; health and wellbeing camps. | |

|

Karalundi Peer Support and Skills Training Program 52 (Gray, Sputore et al 1998) |

RA5 – WA School Setting |

Primary, high school and TAFE students aged 10‐20 y. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ten programs aimed at: developing students' interpersonal, problem‐solving and decision‐making skills; quit smoking; drug; alcohol and petrol sniffing education; sex education, arts and crafts, general health promotion; eye, ear and nose care and the use of natural medicines. | ||

|

Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service 54 (Homer, Foureur et al 2012) |

RA1 – NSW PHC Setting |

Pregnant Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women and non‐Indigenous women having an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander baby | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A unique model of antenatal care that addresses stress, smoking and alcohol consumption in pregnancy along with other care. | ||

|

Watharoung Koori Youth Prevention Programs 74 (Milward 2009) |

RA1 – Vic Community Setting |

Aboriginal Youth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | A variety of programs in partnership with other organisations to prevention the use of alcohol and other drugs. The programs are designed to empower youth, strengthen individual Koori identity and learn more about their culture through camps, surfing competitions and an AFL football program. | |||

|

The Chronic Disease Self‐Management Project 75 (Mobbs, Nguyen et al 2003) |

RA5 – NT Community and PHC Settings |

Patients previously diagnosed with diabetes and/or hypertension with or without renal involvement | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Self‐care program to develop skills including changing behaviour; smoking, nutrition, physical activity and weight loss. Building family and community healthy lifestyle infrastructure using community empowerment framework. Production of local resources (booklets and videos) including HP messages. Establishment of women's healthy weight groups, walking groups and tobacco action initiative. | |

|

Awareness and Self‐Management Programme 81 (Payne 2013) |

RA3 – QLD Community Setting |

Women with type 2 diabetes or identified has having an elevated risk of developing disease. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Support groups involving information sessions on self‐management strategies; grief and loss; health ownership and concepts of shared knowledge; and diet and exercise. | |||

|

Indigenous Surf Programs 85 (Rynne, Rossi et al 2012) |

Multiple RAs – NSW, QLD, Vic and SA Community and School Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (three sites focused on youth) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Five surfing programs across four states. Aim to foster connection to culture, identity, promote physical activity and social connection. | |||

|

WuChopperen Drug Alcohol and Other Substances program 90 (Strempel and Australian National Council on Drugs 2004) |

RA 1‐3 – QLD Community and PHC Settings |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Provides counselling and support for young people in areas of physical, social and emotional health, and coordinates and delivers alcohol and other drug education to staff and health facilitators. |

Abbreviations: A, alcohol; AFL, Australian Football League; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive heart failure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IHD ischaemic heart disease; N, nutrition; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; P, physical activity; PHC, Primary Health Care; QLD, Queensland; RA, remote area; S, smoking; SA, South Australia; So, social and emotional wellbeing; TAFE Technical and Further Education; TAS, Tasmania; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.