Abstract

Background

The recently introduced 2017 World Workshop on the classification of periodontitis, incorporating stages and grades of disease, aims to link disease classification with approaches to prevention and treatment, as it describes not only disease severity and extent but also the degree of complexity and an individual's risk. There is, therefore, a need for evidence‐based clinical guidelines providing recommendations to treat periodontitis.

Aim

The objective of the current project was to develop a S3 Level Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) for the treatment of Stage I–III periodontitis.

Material and Methods

This S3 CPG was developed under the auspices of the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP), following the methodological guidance of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). The rigorous and transparent process included synthesis of relevant research in 15 specifically commissioned systematic reviews, evaluation of the quality and strength of evidence, the formulation of specific recommendations and consensus, on those recommendations, by leading experts and a broad base of stakeholders.

Results

The S3 CPG approaches the treatment of periodontitis (stages I, II and III) using a pre‐established stepwise approach to therapy that, depending on the disease stage, should be incremental, each including different interventions. Consensus was achieved on recommendations covering different interventions, aimed at (a) behavioural changes, supragingival biofilm, gingival inflammation and risk factor control; (b) supra‐ and sub‐gingival instrumentation, with and without adjunctive therapies; (c) different types of periodontal surgical interventions; and (d) the necessary supportive periodontal care to extend benefits over time.

Conclusion

This S3 guideline informs clinical practice, health systems, policymakers and, indirectly, the public on the available and most effective modalities to treat periodontitis and to maintain a healthy dentition for a lifetime, according to the available evidence at the time of publication.

Keywords: clinical guideline, grade, health policy, oral health, periodontal therapy, periodontitis, stage

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. The health problem

1.1.1. Definition

Periodontitis is characterized by progressive destruction of the tooth‐supporting apparatus. Its primary features include the loss of periodontal tissue support manifest through clinical attachment loss (CAL) and radiographically assessed alveolar bone loss, presence of periodontal pocketing and gingival bleeding (Papapanou et al., 2018). If untreated, it may lead to tooth loss, although it is preventable and treatable in the majority of cases.

1.1.2. Importance

Periodontitis is a major public health problem due to its high prevalence, and since it may lead to tooth loss and disability, it negatively affects chewing function and aesthetics, is a source of social inequality, and significantly impairs quality of life. Periodontitis accounts for a substantial proportion of edentulism and masticatory dysfunction, has a negative impact on general health and results in significant dental care costs (Tonetti, Jepsen, Jin, & Otomo‐Corgel, 2017).

1.1.3. Pathophysiology

Periodontitis is a chronic multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic dental plaque biofilms.

1.1.4. Prevalence

Periodontitis is the most common chronic inflammatory non‐communicable disease of humans. According to the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study, the global age‐standardized prevalence (1990–2010) of severe periodontitis was 11.2%, representing the sixth‐most prevalent condition in the world (Kassebaum et al., 2014), while in the Global Burden of Disease 2015 study, the prevalence of severe periodontitis was estimated in 7.4% (Kassebaum et al., 2017). The prevalence of milder forms of periodontitis may be as high as 50% (Billings et al., 2018).

1.1.5. Consequences of failure to treat

Untreated or inadequately treated periodontitis leads to the loss of tooth‐supporting tissues and teeth. Severe periodontitis, along with dental caries, is responsible for more years lost to disability than any other human disease (GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2018). Furthermore, periodontal infections are associated with a range of systemic diseases leading to premature death, including diabetes (Sanz et al., 2018), cardiovascular diseases (Sanz et al., 2019; Tonetti, Van Dyke, & Working Group 1 of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop, 2013) or adverse pregnancy outcomes (Sanz, Kornman, & Working Group 3 of Joint EFP/AAP Workshop, 2013).

1.1.6. Economic importance

On a global scale, periodontitis is estimated to cost $54 billion in direct treatment costs and further $25 billion in indirect costs (GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2018). Periodontitis contributes significantly to the cost of dental diseases due to the need to replace teeth lost to periodontitis. The total cost of dental diseases, in 2015, was estimated to be of $544.41 billion, being $356.80 billion direct costs, and $187.61 billion indirect costs (Righolt, Jevdjevic, Marcenes, & Listl, 2018).

2. AIM OF THE GUIDELINE

This guideline aims to highlight the importance and need for scientific evidence in clinical decision‐making in the treatment of patients with periodontitis stages I to III. Its main objective is therefore to support the evidence‐based recommendations for the different interventions used at the different steps of periodontal therapy, based on the best available evidence and/or expert consensus. In so doing, this guideline aims to improve the overall quality of periodontal treatment in Europe, reduce tooth loss associated with periodontitis and ultimately improve overall systemic health and quality of life. A separate guideline covering the treatment of Stage IV periodontitis will be published.

2.1. Target users of the guideline

Dental and medical professionals, together with all stakeholders related to health care, particularly oral health, including patients.

2.2. Targeted environments

Dental and medical academic/hospital environments, clinics and practices.

2.3. Targeted patient population

People with periodontitis stages I to III.

People with periodontitis stages I to III following successful treatment.

2.4. Exceptions from the guideline

This guideline did not consider the health economic cost–benefit ratio, since (a) it covers multiple different countries with disparate, not readily comparable health systems, and (b) there is a paucity of sound scientific evidence available addressing this question. This guideline did not consider the treatment of gingivitis (although management of gingivitis is considered as an indirect goal in some interventions evaluated), the treatment of Stage IV periodontitis, necrotising periodontitis, periodontitis as manifestation of systemic diseases and mucogingival conditions.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. General framework

This guideline was developed following methodological guidance published by the Standing Guideline Commission of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) (https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/awmf‐regelwerk/awmf‐guidance.html) and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group (https://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

The guideline was developed under the auspices of the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) and overseen by the EFP Workshop Committee. This guideline development process was steered by an Organizing Committee and a group of methodology consultants designated by the EFP. All members of the Organizing Committee were part of the EFP Workshop Committee.

To ensure adequate stakeholder involvement, the EFP established a guideline panel involving dental professionals representing 36 national periodontal societies within the EFP (Table 1a).

TABLE 1a.

Guideline panel

| Scientific society/organization | Delegate(s) |

|---|---|

| European Federation of Periodontology |

Organizing Committee, Working Group Chairs (in alphabetic order): Tord Berglundh, Iain Chapple, David Herrera, Søren Jepsen, Moritz Kebschull, Mariano Sanz, Anton Sculean, Maurizio Tonetti |

|

Methodologists: Ina Kopp, Paul Brocklehurst, Jan Wennström | |

|

Clinical Experts: Anne Merete Aass, Mario Aimetti, Bahar Eren Kuru, Georgios Belibasakis, Juan Blanco, Nagihan Bostanci, Darko Bozic, Philippe Bouchard, Nurcan Buduneli, Francesco Cairo, Elena Calciolari, Maria Clotilde Carra, Pierpaolo Cortellini, Jan Cosyn, Francesco D'Aiuto, Bettina Dannewitz, Monique Danser, Korkud Demirel, Jan Derks, Massimo de Sanctis, Thomas Dietrich, Christof Dörfer, Henrik Dommisch, Nikos Donos, Peter Eickholz, Elena Figuero, William Giannobile, Moshe Goldstein, Filippo Graziani, Thomas Kocher, Eija Kononen, Bahar Eren Kuru, France Lambert, Luca Landi, Nicklaus Lang, Bruno Loos, Rodrigo López, Pernilla Lundberg, Eli Machtei, Phoebus Madianos, Conchita Martín, Paula Matesanz, Jörg Meyle, Ana Molina, Eduardo Montero, José Nart, Ian Needleman, Luigi Nibali, Panos Papapanou, Andrea Pilloni, David Polak, Ioannis Polyzois, Philip Preshaw, Marc Quirynen, Christoph Ramseier, Stefan Renvert, Giovanni Salvi, Ignacio Sanz‐Sánchez, Lior Shapira, Dagmar Else Slot, Andreas Stavropoulos, Xavier Struillou, Jean Suvan, Wim Teughels, Cristiano Tomasi, Leonardo Trombelli, Fridus van der Weijden, Clemens Walter, Nicola West, Gernot Wimmer | |

| Scientific Societies | |

| European Society for Endodontology | Lise Lotte Kirkevang |

| European Prosthodontic Association | Phophi Kamposiora |

| European Association of Dental Public Health | Paula Vassallo |

| European Federation of Conservative Dentistry | Laura Ceballos |

| Other organisations | |

| Council of European Chief Dental Officers | Kenneth Eaton |

| Council of European Dentists | Paulo Melo |

| European Dental Hygienists' Federation | Ellen Bol‐van den Hil |

| European Dental Students' Association | Daniela Timus |

| Platform for Better Oral Health in Europe | Kenneth Eaton |

These delegates were nominated, participated in the guideline development process and had voting rights in the consensus conference. For the guideline development process, delegates were assigned to four Working Groups that were chaired by the members of the Organizing Committee and advised by the methodology consultants. This panel was supported by key stakeholders from European scientific societies with a strong professional interest in periodontal care and from European organizations representing key groups within the dental profession, and key experts from non‐EFP member countries, such as North America (Table 1b).

TABLE 1b.

Key stakeholders contacted and participants

| Institution | Acronym | Answer a | Representative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association for Dental Education in Europe | ADEE | No answer | No representative |

| Council of European Chief Dental Officers | CECDO | Participant | Ken Eaton/Paula Vassallo |

| Council of European Dentists | CED | Participant | Paulo Melo |

| European Association of Dental Public Health | EADPH | Participant | Paula Vassallo |

| European Dental Hygienists Federation | EDHF | Participant | Ellen Bol‐van den Hil |

| European Dental Students' Association | EDSA | Participant | Daniella Timus |

| European Federation of Conservative Dentistry | EFCD | Participant | Laura Ceballos |

| European Orthodontic Society | EOS | No answer | No representative |

| European Prosthodontic Association | EPA | Participant | Phophi Kamposiora |

| European Society of Endodontology | ESE | Participant | Lise Lotte Kirkevang |

| Platform for Better Oral Health in Europe | PBOHE | Participant | Kenneth Eaton |

Messages sent 20 March 2019; reminder sent June 18.

In addition, EFP engaged an independent guideline methodologist to advise the panel and facilitate the consensus process (Prof. Dr. med. Ina Kopp). The guideline methodologist had no voting rights.

EFP and the guideline panel tried to involve patient organizations but were not able to identify any regarding periodontal diseases at European level. In a future update, efforts will be undertaken to include the perspective of citizens/patients (Brocklehurst et al., 2018).

3.2. Evidence synthesis

3.2.1. Systematic search and critical appraisal of guidelines

To assess and utilize existing guidelines during the development of the present guideline, well‐established guideline registers and the websites of large periodontal societies were electronically searched for potentially applicable guideline texts:

Guideline International Network (GIN)

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)

Canadian Health Technology Assessment (CADTH)

European Federation for Periodontology (EFP)

American Academy of Periodontology (AAP)

American Dental Association (ADA)

The last search was performed on 30 September 2019. Search terms used were “periodont*,” “Periodontal,” “Guidelines” and “Clinical Practice Guidelines.” In addition, content was screened by hand searches. See Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Results of the guideline search

| Database | Identified, potentially relevant guidelines | Critical appraisal |

|---|---|---|

| Guideline International Network (GIN) International Guidelines Library a | Comprehensive periodontal therapy: a statement by the American Academy of Periodontology. American Academy of Periodontology. NGC:008726 (2011) | 8 years old, recommendations not based on systematic evaluation of evidence, not applicable |

| DG PARO S3 guideline (Register Number 083‐029)— Adjuvant systemic administration of antibiotics for subgingival instrumentation in the context of systematic periodontitis treatment (2018) | Very recent, high methodological standard, very similar outcome measures ‐ relevant | |

| HealthPartners Dental Group and Clinics guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of periodontal diseases. HealthPartners Dental Group. NGC:008848 (2011) | 8 years old, unclear methodology, not applicable | |

|

“Dentistry” category |

Health Partners Dental Group and Clinics Caries Guideline | Not applicable |

| The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) b | No thematically relevant hits | Not applicable |

| National Guideline Clearinghouse (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) c | No thematically relevant hits | Not applicable |

| Canadian Health Technology Assessment (CADTH) d | Periodontal Regenerative Procedures for Patients with Periodontal Disease: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness (2010) | 9‐year‐old review article, not applicable |

| Treatment of Periodontal Disease: Guidelines and Impact (2010) | 9‐year‐old review article, not applicable | |

| Dental Scaling and Root Planing for Periodontal Health: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness, Cost‐effectiveness, and Guidelines (2016) | Unclear methodology (follow‐up, outcome variables, recommendations, guideline group), not applicable | |

| Dental Cleaning and Polishing for Oral Health: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness, Cost‐effectiveness and Guidelines (2013) | Unclear methodology (follow‐up, outcome variables, recommendations, guideline group), not applicable | |

| European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) e | No thematically relevant hits | Not applicable |

| American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) f | The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology Editors' Consensus: Periodontitis and Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease (2009) | Unclear methodology, 10 year‐old consensus‐based article, only limited clinically applicably recommendations, not applicable |

| Comprehensive Periodontal Therapy: A Statement by the American Academy of Periodontology (2011) | Unclear methodology (follow‐up, outcome variables, recommendations, guideline group), almost a decade old, not applicable | |

| Academy Statements on Gingival Curettage (2002), Local Delivery (2006), Risk Assessment (2008), Efficacy of Lasers (2011) | Unclear methodology, 10‐year‐old consensus‐based article, only limited clinically applicably recommendations, not applicable | |

| American Dental Association (ADA) g | Nonsurgical Treatment of Chronic Periodontitis Guideline (2015) | Outcome variable CAL (not PPD), no minimal follow‐up—not applicable |

Only guidelines published in English and with full texts available were included. The methodological quality of these guideline texts was critically appraised using the AGREE II framework (https://www.agreetrust.org/agree‐ii/).

Most of the identified guidelines/documents were considered not applicable due to (a) their age, (b) their methodological approach, or (c) their inclusion criteria. The recent German S3 guideline (Register Number 083‐029) was found to be potentially relevant, scored highest in the critical appraisal using AGREE II and was, therefore, used to inform the guideline development process.

3.2.2. Systematic search and critical appraisal of the literature

For this guideline, a total of 15 systematic reviews (SRs) were conducted to support the guideline development process (Carra et al., 2020; Dommisch, Walter, Dannewitz, & Eickholz, 2020; Donos et al., 2019; Figuero, Roldan, et al., 2019; Herrera et al., 2020; Jepsen et al., 2019; Nibali et al., 2019; Polak et al., 2020; Ramseier et al., 2020; Salvi et al., 2019; Sanz‐Sanchez et al., 2020; Slot, Valkenburg, & van der Weijden, 2020; Suvan et al., 2019; Teughels et al., 2020; Trombelli et al., 2020). The corresponding manuscripts are published within this special issue of the Journal of Clinical Periodontology.

All SRs were conducted following the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses” (PRISMA) framework (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009).

3.2.3. Focused questions

In all 15 systematic reviews, focused questions in PICO(S) format (Guyatt et al., 2011) were proposed by the authors in January 2019 to a panel comprising the working group chairs and the methodological consultants, in order to review and approve them (Table 3). The panel took great care to avoid overlaps or significant gaps between the SRs, so they would truly cover all possible interventions currently undertaken in periodontal therapy.

TABLE 3.

PICOS questions addressed by each Systematic Review

| Reference | Systematic review title | Final PICOS (as written in manuscripts) |

|---|---|---|

| Suvan et al. (2019) | Subgingival Instrumentation for Treatment of Periodontitis. A Systematic Review. | #1. In patients with periodontitis, what is the efficacy of subgingival instrumentation performed with hand or sonic/ultrasonic instruments in comparison with supragingival instrumentation or prophylaxis in terms of clinical and patient reported outcomes? |

| #2. In patients with periodontitis, what is the efficacy of nonsurgical subgingival instrumentation performed with sonic/ultrasonic instruments compared to subgingival instrumentation performed with hand instruments or compared to the subgingival instrumentation performed with a combination of hand and sonic/ultrasonic instruments in terms of clinical and patient‐reported outcomes? | ||

| #3. In patients with periodontitis, what is the efficacy of full mouth delivery protocols (within 24 hr) in comparison with quadrant or sextant wise delivery of subgingival mechanical instrumentation in terms of clinical and patient‐reported outcomes? | ||

| Salvi et al. (2019) | Adjunctive laser or antimicrobial photodynamic therapy to non‐surgical mechanical instrumentation in patients with untreated periodontitis. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. | #1. In patients with untreated periodontitis, does laser application provide adjunctive effects to non‐surgical mechanical instrumentation alone? |

| #2. In patients with untreated periodontitis, does application of a PTD provide adjunctive effects to non‐surgical mechanical instrumentation alone? | ||

| Donos et al. (2019) | The adjunctive use of host modulators in non‐surgical periodontal therapy. A systematic review of randomized, placebo‐controlled clinical studies | In patients with periodontitis, what is the efficacy of adding host modulating agents instead of placebo to NSPT in terms of probing pocket depth (PPD) reduction? |

| Sanz‐Sanchez et al. (2020) | Efficacy of access flaps compared to subgingival debridement or to different access flap approaches in the treatment of periodontitis. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. | #1. In patients with periodontitis (population), how effective are access flaps (intervention) as compared to subgingival debridement (comparison) in attaining PD reduction (primary outcome)? |

| #2. In patients with periodontitis (population), does the type of access flaps (intervention and control) impact PD reduction (primary outcome)? | ||

| Polak et al. (2020) | The Efficacy of Pocket Elimination/Reduction Surgery Vs. Access Flap: A Systematic Review | In adult patients with periodontitis after initial non‐surgical cause‐related therapy and residual PPD of 5 mm or more, what is the efficacy of pocket elimination/reduction surgery in comparison with access flap surgery? |

| Teughels et al. (2020) | Adjunctive effect of systemic antimicrobials in periodontitis therapy. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. | In patients with periodontitis, which is the efficacy of adjunctive systemic antimicrobials, in comparison with subgingival debridement plus a placebo, in terms of probing pocket depth (PPD) reduction, in randomized clinical trials with at least 6 months of follow‐up. |

| Herrera et al. (2020) | Adjunctive effect of locally delivered antimicrobials in periodontitis therapy. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. | In adult patients with periodontitis, which is the efficacy of adjunctive locally delivered antimicrobials, in comparison with subgingival debridement alone or plus a placebo, in terms of probing pocket depth (PPD) reduction, in randomized clinical trials with at least 6 months of follow‐up. |

| Nibali et al. (2019) | Regenerative surgery versus access flap for the treatment of intra‐bony periodontal defects: A systematic review and meta‐analysis | #1. Does regenerative surgery of intraosseous defects provide additional clinical benefits measured as Probing Pocket Depth (PPD) reduction, Clinical Attachment Level (CAL) gain, Recession (Rec) and Bone Gain (BG) in periodontitis patients compared with access flap? |

| #2. Is there a difference among regenerative procedures in terms of clinical and radiographic gains in intrabony defects? | ||

| Jepsen et al. (2019) | Regenerative surgical treatment of furcation defects: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials | #1. What is the efficacy of regenerative periodontal surgery in terms of tooth loss, furcation conversion and closure, horizontal clinical attachment level (HCAL) and bone level (HBL) gain as well as other periodontal parameters in teeth affected by periodontitis‐related furcation defects, at least 12 months after surgery? |

| #2. NM: to establish a ranking in efficacy of the treatment options and to identify the best surgical technique. | ||

| Dommisch et al. (2020) | Resective surgery for the treatment of furcation involvement: A systematic review | What is the benefit of resective surgical periodontal therapy (i.e. root amputation or resection, root separation, tunnel preparation) in (I) subjects with periodontitis who have completed a cycle of non‐surgical periodontal therapy and exhibit Class II and III furcation involvement (P) compared to individuals suffering from periodontitis and exhibiting class II and III furcation involvement not being treated with resective surgical periodontal therapy but were not treated at all, treated exclusively by subgingival debridement or access flap surgery (C) with respect to 1) tooth survival (primary outcome), 2) vertical probing attachment (PAL‐V) gain and 3) reduction of probing pocket depth (PPD) (secondary outcomes) (O) evidenced by randomized controlled clinical trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies and case series with at least 12 months of follow‐up (survival, PAL‐V, PPD) (S), respectively. |

| Slot et al. (2020) | Mechanical plaque removal of periodontal maintenance patients: A systematic review and network meta‐analysis | #1. In periodontal maintenance patients, what is the effect on plaque removal and parameters of periodontal health of the following: Power toothbrushes as compared to manual toothbrushes? |

| #2. In periodontal maintenance patients, what is the effect on plaque removal and parameters of periodontal health of the following: Interdental oral hygiene devices compared to no interdental cleaning as adjunct to toothbrushing? | ||

| #3. In periodontal maintenance patients, what is the effect on plaque removal and parameters of periodontal health of the following: Different interdental cleaning devices as adjuncts to toothbrushing | ||

| Carra et al. (2020) | Promoting behavioural changes to improve oral hygiene in patients with periodontal diseases: a systematic review of the literature. | What is the efficacy of behavioural interventions aimed to promote OH in patients with periodontal diseases (gingivitis/periodontitis), in improving clinical plaque and bleeding indices? |

| Ramseier et al. (2020) | Impact of risk factor control interventions for smoking cessation and promotion of healthy lifestyles in patients with periodontitis: a systematic review | What is the efficacy of health behaviour change interventions for smoking cessation, diabetes control, physical exercise (activity), change of diet, carbohydrate (dietary sugar) reduction and weight loss provided in patients with periodontitis?“. |

| Figuero, Roldan, et al. (2019) | Efficacy of adjunctive therapies in patients with gingival inflammation. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. | In systemically healthy humans with dental plaque‐induced gingival inflammation (with or without attachment loss, but excluding untreated periodontitis patients), what is the efficacy of agents used adjunctively to mechanical plaque control (either self‐performed or professionally delivered), as compared to mechanical plaque control combined with a negative control, in terms of changes in gingival inflammation (through gingivitis or bleeding indices)? |

| Trombelli et al. (2020) | Efficacy of alternative or additional methods to professional mechanical plaque removal during supportive periodontal therapy. A systematic review and meta‐analysis | #1. What is the efficacy of alternative methods to professional mechanical plaque removal (PMPR) on progression of attachment loss during supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) in periodontitis patients? |

| #2. What is the efficacy of additional methods to professional mechanical plaque removal (PMPR) on progression of attachment loss during supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) in periodontitis patients? |

3.2.4. Relevance of outcomes

A narrative review paper was commissioned for this guideline (Loos & Needleman, 2020) to evaluate the possible outcome measures utilized to evaluate the efficacy of periodontal therapy in relation to true patient‐centred outcomes like tooth retention/loss. The authors found that the commonly reported outcome variable with the best demonstrated predictive potential for tooth loss was the reduction in periodontal probing pocket depth (PPD). Therefore, for this guideline, PPD reduction was used as primary outcome for those systematic reviews not addressing periodontal regeneration, and where tooth survival data were not reported. When reviewing regenerative interventions, gains in clinical attachment were used as the primary outcome measure. To avoid introducing bias by including possibly spurious findings of studies with very short follow‐up, a minimal follow‐up period of six months was requested for all reviews.

3.2.5. Search strategy

All SRs utilized a comprehensive search strategy of at least two different databases, supplemented by a hand search of periodontal journals and the reference lists of included studies.

In all SRs, the electronic and manual search, as well as the data extraction, was done in parallel by two different investigators.

3.2.6. Quality assessment of included studies

In all SRs, the risk of bias of controlled clinical trials was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob‐2‐revised‐cochrane‐risk‐bias‐tool‐randomized‐trials). For observational studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

3.2.7. Data synthesis

Where applicable, the available evidence was summarized by means of meta‐analysis, or other tools aimed for pooling data (network meta‐analysis, Bayesian network meta‐analysis).

3.3. From evidence to recommendation: structured consensus process

The structured consensus development conference was held during the XVI European Workshop in Periodontology in La Granja de San Ildefonso Segovia, Spain, on 10–13 November 2019. Using the 15 SRs as background information, evidence‐based recommendations were formally debated by the guideline panel using the format of a structured consensus development conference, consisting of small group discussions and open plenary were the proposed recommendations were presented, voted and adopted by consensus and Murphy et al. (1998).

In the small group phase, delegates convened in four working groups addressing the following subtopics: (a) “periodontitis stages I and II”; (b) “periodontitis Stage III”; (c) “periodontitis Stage III with intraosseous defects and/or furcations”; and (d) “supportive periodontal care.” These working groups were directed by two chairpersons belonging to the EFP Workshop Committee. With the support of an expert in methodology in each working group, recommendations and draft background texts were generated and subsequently presented, debated and put to a vote in the plenary of all delegates. During these plenary sessions, the guideline development process and discussions and votes were overseen and facilitated by the independent guideline methodologist (I.K.). The plenary votes were recorded using an electronic voting system, checked for plausibility in then introduced into the guideline text.

The consensus process was conducted as follows:

3.3.1. Plenary 1

Introduction to guideline methodology (presentation, discussion) by the independent guideline methodologist (I.K.).

3.3.2. Working group Phase 1

Peer evaluation of declarations of interest and management of conflicts.

Presentation of the evidence (SR results) by group chairs and methodology consultants.

Invitation of all members of the working group to reflect critically on the quality of available evidence by group chairs, considering GRADE criteria.

-

Structured group discussion:

-

○

development of draft recommendation and their grading, considering GRADE‐criteria.

-

○

development of draft background texts, considering GRADE criteria.

-

○

invitation to comment draft recommendations and background text to suggest reasonable amendments by group chairs.

-

○

collection and merging of amendments by group chairs.

-

○

initial voting within the working group on recommendations and guideline text to be presented as group result in the plenary.

-

○

3.3.3. Plenary 2

Presentation of working group results (draft recommendations and background text) by working group chairs.

Invitation to formulate questions, statements and reasonable amendments of the plenary by the independent guideline methodologist/facilitator.

Answering of questions by working group chairpersons.

Collection and merging of amendments by independent moderator.

Preliminary vote on all suggestions provided by the working groups and all reasonable amendments.

Assessment of the strength of consensus.

Opening debate, where no consensus was reached or reasonable need for discussion was identified.

Formulation of tasks to be solved within the working groups.

3.3.4. Working group Phase 2

Discussion of tasks and potential amendments raised by the plenary.

Formulation of reasonable and justifiable amendments, considering the GRADE framework.

Initial voting within the working group on recommendations and guideline text for plenary.

3.3.5. Plenary 3

Presentation of working group results by working group chairpersons.

Invitation to formulate questions, statements and reasonable amendments of the plenary by the independent moderator.

Collection and merging of amendments by independent moderator.

Preliminary vote.

Assessment of the strength of consensus.

Opening debate, where no consensus was reached or reasonable need for discussion was identified.

Formulation of reasonable alternatives.

Final vote of each recommendation.

3.4. Definitions: rating the quality of evidence, grading the strength of recommendations and determining the strength of consensus

For all recommendations and statements, this guideline makes transparent.

the underlying quality of evidence, reflecting the degree of certainty/uncertainty of the evidence and robustness of study results

the grade of the recommendation, reflecting criteria of considered judgement the strength of consensus, indicating the degree of agreement within the guideline panel and thus reflecting the need of implementation

3.4.1. Quality of Evidence

The quality of evidence was assessed using a recommended rating scheme (Balshem et al., 2011; Schunemann, Zhang, Oxman, & Expert Evidence in Guidelines, 2019).

3.4.2. Strength of Recommendations

The grading of the recommendations used the grading scheme (Table 4) by the German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) and Standing Guidelines Commission (2012), taking into account not only the quality of evidence, but also considered judgement, guided by the following criteria:

relevance of outcomes and quality of evidence for each relevant outcome

consistency of study results

directness regarding applicability of the evidence to the target population/PICO specifics

precision of effect estimates regarding confidence intervals

magnitude of the effects

balance of benefit and harm

ethical, legal, economic considerations

patient preferences

TABLE 4.

Strength of recommendations: grading scheme (German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) and Standing Guidelines Commission, 2012)

| Grade of recommendation grade a | Description | Syntax |

|---|---|---|

| A | Strong recommendation |

We recommend (↑↑)/ We recommend not to (↓↓) |

| B | Recommendation |

We suggest to (↑)/ We suggest not to (↓) |

| 0 | Open recommendation | May be considered (↔) |

If the group felt that evidence was not clear enough to support a recommendation, Statements were formulated, including the need (or not) of additional research.

The grading of the quality of evidence and the strength of a recommendation may therefore differ in justified cases.

3.4.3. Strength of consensus

The consensus determination process followed the recommendations by the German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) and Standing Guidelines Commission (2012). In case, consensus could not be reached, different points of view were documented in the guideline text. See Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Strength of consensus: determination scheme (German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) and Standing Guidelines Commission, 2012)

| Unanimous consensus | Agreement of 100% of participants |

| Strong consensus | Agreement of > 95% of participants |

| Consensus | Agreement of 75%–95% of participants |

| Simple majority | Agreement of 50%–74% of participants |

| No consensus | Agreement of < 50% of participants |

3.5. Editorial independence

3.5.1. Funding of the guideline

The development of this guideline and its subsequent publication were financed entirely by internal funds of the European Federation of Periodontology, without any support from industry or other organizations.

3.5.2. Declaration of interests and management of potential conflicts

All members of the guideline panel declared secondary interests using the standardized form provided by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) (International Committee of Medical Editors).

Management of conflict of interests (CoIs) was discussed in the working groups, following the principles provided by the Guidelines International Network (Schunemann et al., 2015). According to these principles, panel members with relevant, potential CoI abstained from voting on guideline statements and recommendations within the consensus process.

3.6. Peer review

All 15 systematic reviews, and the position paper on outcome variables commissioned for this guideline, underwent a multistep peer review process. First, the draft documents were evaluated by members of the EFP Workshop Committee and the methodological consultants using a custom‐made appraisal tool to assess (a) the methodological quality of the SRs using the AMSTAR 2 checklist (Shea et al., 2017), and (b) whether all PICO(S) questions were addressed as planned. Detailed feedback was then provided for the SR authors. Subsequently, all 15 systematic reviews and the position paper underwent the regular editorial peer review process defined by the Journal of Clinical Periodontology.

The guideline text was drafted by the chairs of the working groups, in close cooperation with the methodological consultants, and circulated in the guideline group before the workshop. The methodological quality was formally assessed by an outside consultant using the AGREE framework. The guideline was subsequently peer‐reviewed for its publication in the Journal of Clinical Periodontology following the standard evaluation process of this scientific journal.

3.7. Implementation and dissemination plan

For this guideline, a multistage dissemination and implementation strategy will be actioned by the EFP, supported by a communication campaign.

This will include the following:

Publication of the guideline and the underlying systematic reviews and position paper as an Open Access special issue of the Journal of Clinical Periodontology

Local uptake from national societies, either by Commentary, Adoption, or Adaptation (Schunemann et al., 2017)

Generation of educational material for dental professionals and patients, dissemination via the EFP member societies

Dissemination via educational programmes on dental conferences

Dissemination via EFP through European stakeholders via National Societies, members of EFP

Long‐term evaluation of the successful implementation of the guideline by poll of EFP members.

The timeline of the guideline development process is detailed in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Timeline of the guideline development process

| Time point | Action |

|---|---|

| April 2018 | Decision by European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) General Assembly to develop comprehensive treatment guidelines for periodontitis |

| May–September 2018 | EFP Workshop Committee assesses merits and disadvantages of various established methodologies and their applicability to the field |

| September 2018 | EFP Workshop Committee decides on/invites (a) topics covered by proposed guideline, (b) working groups and chairs, (c) systematic reviewers, and (d) outcomes measures |

| End of year 2018 |

Submission of PICO(S) questions by systematic reviewers to group chairs for internal alignment Decision on consensus group, invitation of stakeholders |

| 21 January 2019 | Organizing and Advisor Committee meeting. Decision on PICO(S) and information sent to reviewers |

| March–June 2019 | Submission of Systematic reviews by reviewers, initial assessment by workshop committee |

| June–October 2019 | Peer review and revision process, Journal of Clinical Periodontology |

| September 2019 | Submission of declarations of interest by all delegates |

| Before workshop | Electronic circulation of reviews and guideline draft |

| 10–13 November 2019 | Workshop in La Granja with moderated formalized consensus process |

| December 2019–January 2020 | Formal stakeholder consultation, finalization of guideline method report and background text |

| April 2020 | Publication of guideline and underlying Systematic Reviews in the Journal of Clinical Periodontology |

3.8. Validity and update process

The guideline is valid until 2025. However, the EFP, represented by the members of the Organizing Committee, will continuously assess current developments in the field. In case of major changes of circumstances, for example new relevant evidence, they will trigger an update of the guideline to potentially amend the recommendations. It is planned to update the current guideline regularly on demand in form of a living guideline.

4. PERIODONTAL DIAGNOSIS AND CLASSIFICATION

Periodontal diagnosis has been followed according to the classification scheme defined in the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri‐Implant Diseases and Conditions (Caton et al., 2018; Chapple et al., 2018; Jepsen et al., 2018; Papapanou et al., 2018).

According to this classification:

A case of clinical periodontal health is defined by the absence of inflammation [measured as presence of bleeding on probing (BOP) at less than 10% sites] and the absence of attachment and bone loss arising from previous periodontitis.

A gingivitis case is defined by the presence of gingival inflammation, as assessed by BOP at ≥10% sites and absence of detectable attachment loss due to previous periodontitis. Localized gingivitis is defined as 10%–30% bleeding sites, while generalized gingivitis is defined as >30% bleeding sites

A periodontitis case is defined by the loss of periodontal tissue support, which is commonly assessed by radiographic bone loss or interproximal loss of clinical attachment measured by probing. Other meaningful descriptions of periodontitis include the number and proportions of teeth with probing pocket depth over certain thresholds (commonly >4 mm with BOP and ≥6 mm), the number of teeth lost due to periodontitis, the number of teeth with intrabony lesions and the number of teeth with furcation lesions.

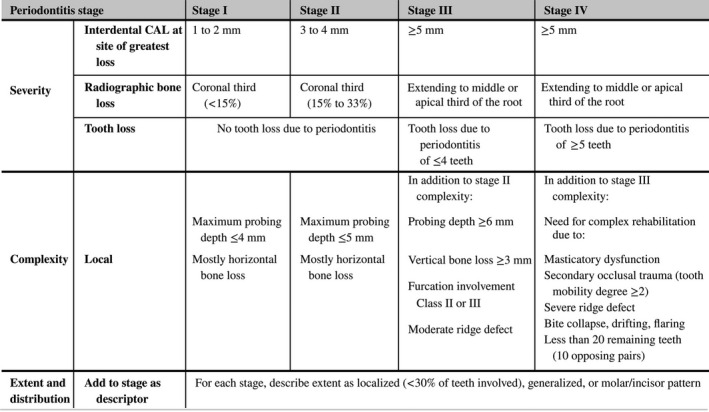

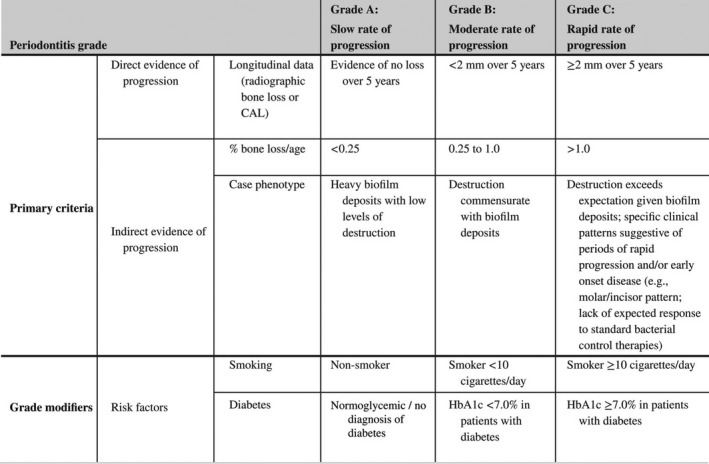

An individual case of periodontitis should be further characterized using a matrix that describes the stage and grade of the disease. Stage is largely dependent upon the severity of disease at presentation, as well as on the anticipated complexity of case management, and further includes a description of extent and distribution of the disease in the dentition. Grade provides supplemental information about biological features of the disease including a history‐based analysis of the rate of periodontitis progression; assessment of the risk for further progression; analysis of possible poor outcomes of treatment; and assessment of the risk that the disease or its treatment may negatively affect the general health of the patient. The staging, which is dependent on the severity of the disease and the anticipated complexity of case management, should be the basis for the patient's treatment plan based on the scientific evidence of the different therapeutic interventions. The grade, however, since it provides supplemental information on the patient's risk factors and rate of progression, should be the basis for individual planning of care (Tables 7 and 8) (Papapanou et al., 2018; Tonetti, Greenwell, & Kornman, 2018).

After the completion of periodontal therapy, a stable periodontitis patient has been defined by gingival health on a reduced periodontium (bleeding on probing in <10% of the sites; shallow probing depths of 4 mm or less and no 4 mm sites with bleeding on probing). When, after the completion of periodontal treatment, these criteria are met but bleeding on probing is present at >10% of sites, then the patient is diagnosed as a stable periodontitis patient with gingival inflammation. Sites with persistent probing depths ≥4 mm which exhibit BOP are likely to be unstable and require further treatment. It should be recognized that successfully treated and stable periodontitis patients will remain at increased risk of recurrent periodontitis, and hence if gingival inflammation is present adequate measures for inflammation control should be implemented to prevent recurrent periodontitis.

TABLE 7.

Periodontitis stage. Adapted from Tonetti et al. (2018)

The initial Stage should be determined using CAL; if not available then RBL should be used. Information on tooth loss that can be attributed primarily to periodontitis – if available – may modify stage definition. This is the case even in the absence of complexity factors. Complexity factors may shift the Stage to a higher level, for example furcation II or III would shift to either Stage III or IV irrespective of the CAL. The distinction between Stage III and Stage IV is primarily based on complexity factors. For example, a high level of tooth mobility and/or posterior bite collapse would indicate a Stage IV diagnosis. For any given case only some, not all, complexity factors may be present, however, in general it only takes 1 complexity factor to shift the diagnosis to a higher Stage. It should be emphasized that these case definitions are guidelines that should be applied using sound clinical judgment to arrive at the most appropriate clinical diagnosis.

For post‐treatment patients CAL and RBL are still the primary stage determinants. If a stage shifting complexity factor(s) were eliminated by treatment, the stage should not retrogress to a lower stage since the original stage complexity factor should always be considered in maintenance phase management.

Abbreviations: CAL, clinical attachment loss; RBL, radiographic bone loss.

TABLE 8.

Periodontitis grade. Adapted from Papapanou et al. (2018)

Grade should be used as an indicator of the rate of periodontitis progression. The primary criteria are either direct or indirect evidence of progression. Whenever available, direct evidence is used; in its absence indirect estimation is made using bone loss as a function of age at the most affected tooth or case presentation (radiographic bone loss expressed as percentage of root length divided by the age of the subject, RBL/age). Clinicians should initially assume Grade B disease and seek specific evidence to shift towards grade A or C, if available. Once grade is established based on evidence of progression, it can be modified based on the presence of risk factors. CAL, clinical attachment loss; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c; RBL, radiographic bone loss.

4.1. Clinical pathway for a diagnosis of periodontitis

A proposed algorithm has been used by the EFP to assist clinicians with this periodontal diagnosis process when examining a new patient (Tonetti & Sanz, 2019). It consists of four sequential steps:

Identifying a patient suspected of having periodontitis

Confirming the diagnosis of periodontitis

Staging the periodontitis case

Grading the periodontitis case

4.2. Differential Diagnosis

Periodontitis should be differentiated from the following clinical conditions (not an exhaustive list of conditions and diseases):

Gingivitis (Chapple et al., 2018)

Vertical root fracture (Jepsen et al., 2018)

Cervical decay (Jepsen et al., 2018)

Cemental tears (Jepsen et al., 2018)

External root resorption lesions (Jepsen et al., 2018)

Tumours or other systemic conditions extending to the periodontium (Jepsen et al., 2018)

Trauma‐induced local recession (Jepsen et al., 2018)

Endo‐periodontal lesions (Herrera, Retamal‐Valdes, Alonso, & Feres, 2018)

Periodontal abscess (Herrera et al., 2018)

Necrotizing periodontal diseases (Herrera et al., 2018)

4.3. Sequence for the treatment of periodontitis stages I, II and III

Patients, once diagnosed, should be treated according to a pre‐established stepwise approach to therapy that, depending on the disease stage, should be incremental, each including different interventions.

An essential prerequisite to therapy is to inform the patient of the diagnosis, including causes of the condition, risk factors, treatment alternatives and expected risks and benefits including the option of no treatment. This discussion should be followed by agreement on a personalized care plan. The plan might need to be modified during the treatment journey, depending on patient preferences, clinical findings and changes to overall health.

1. The first step in therapy is aimed at guiding behaviour change by motivating the patient to undertake successful removal of supragingival dental biofilm and risk factor control and may include the following interventions:

Supragingival dental biofilm control

Interventions to improve the effectiveness of oral hygiene [motivation, instructions (oral hygiene instructions, OHI)]

Adjunctive therapies for gingival inflammation

Professional mechanical plaque removal (PMPR), which includes the professional interventions aimed at removing supragingival plaque and calculus, as well as possible plaque‐retentive factors that impair oral hygiene practices.

Risk factor control, which includes all the health behavioural change interventions eliminating/mitigating the recognized risk factors for periodontitis onset and progression (smoking cessation, improved metabolic control of diabetes, and perhaps physical exercise, dietary counselling and weight loss).

This first step of therapy should be implemented in all periodontitis patients, irrespective of the stage of their disease, and should be re‐evaluated frequently in order to

Continue to build motivation and adherence, or explore other alternatives to overcome the barriers

Develop skills in dental biofilm removal and modify as required

Allow for the appropriate response of the ensuing steps of therapy

2. The second step of therapy (cause‐related therapy) is aimed at controlling (reducing/eliminating) the subgingival biofilm and calculus (subgingival instrumentation). In addition to this, the following interventions may be included:

Use of adjunctive physical or chemical agents

Use of adjunctive host‐modulating agents (local or systemic)

Use of adjunctive subgingival locally delivered antimicrobials

Use of adjunctive systemic antimicrobials

This second step of therapy should be used for all periodontitis patients, irrespective of their disease stage, only in teeth with loss of periodontal support and/or periodontal pocket formation*.

*In specific clinical situations, such as in the presence of deep probing depths, first and second steps of therapy could be delivered simultaneously (such as for preventing periodontal abscess development).

The individual response to the second step of therapy should be assessed once the periodontal tissues have healed (periodontal re‐evaluation). If the endpoints of therapy (no periodontal pockets >4 mm with bleeding on probing or no deep periodontal pockets [≥6 mm]) have not been achieved, the third step of therapy should be considered. If the treatment has been successful in achieving the endpoints of therapy, patients should be placed in a supportive periodontal care (SPC) programme.

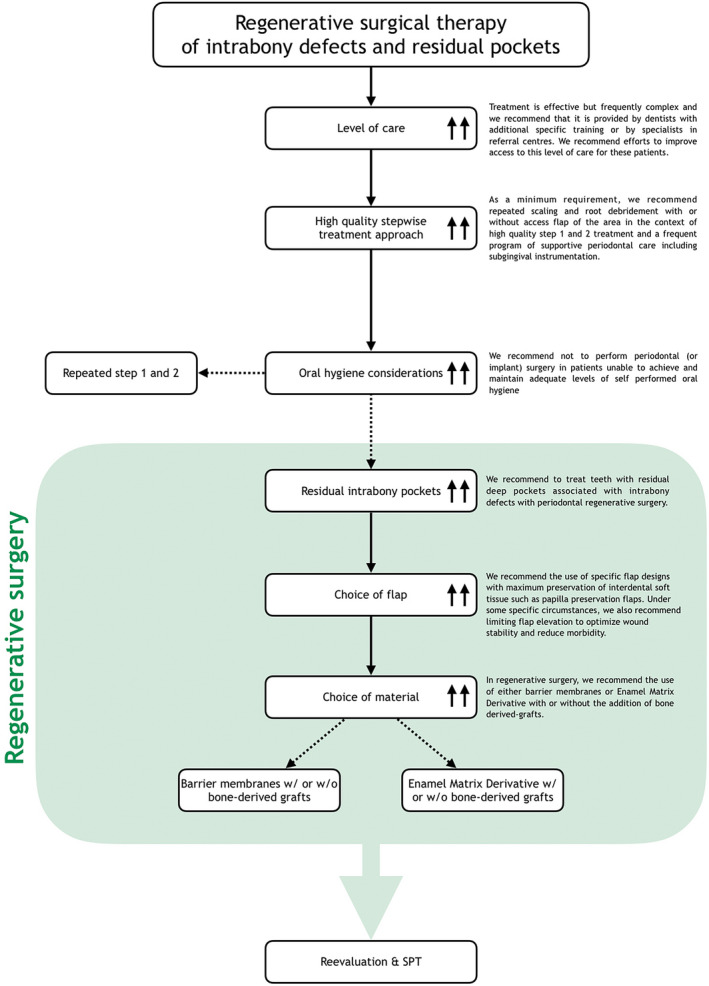

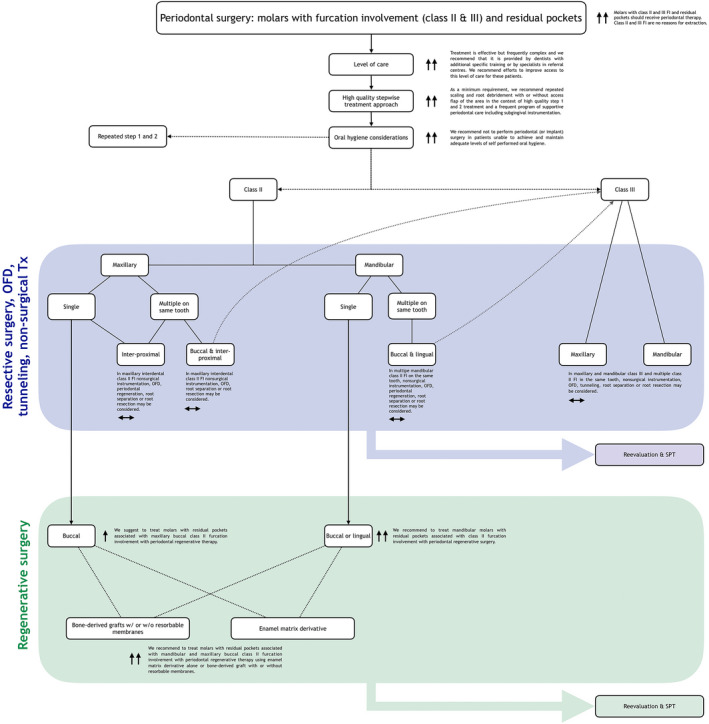

3. The third step of therapy is aimed at treating those areas of the dentition non‐responding adequately to the second step of therapy (presence of pockets ≥4 mm with bleeding on probing or presence of deep periodontal pockets [≥6 mm]), with the purpose of gaining further access to subgingival instrumentation, or aiming at regenerating or resecting those lesions that add complexity in the management of periodontitis (intra‐bony and furcation lesions).

It may include the following interventions:

Repeated subgingival instrumentation with or without adjunctive therapies

Access flap periodontal surgery

Resective periodontal surgery

Regenerative periodontal surgery

When there is indication for surgical interventions, these should be subject to an additional patient consent and specific evaluation of risk factors or medical contra‐indications should be considered.

The individual response to the third step of therapy should be re‐assessed (periodontal re‐evaluation) and ideally the endpoints of therapy should be achieved, and patients should be placed in supportive periodontal care, although these endpoints of therapy may not be achievable in all teeth in severe Stage III periodontitis patients.

4. Supportive periodontal care is aimed at maintaining periodontal stability in all treated periodontitis patients combining preventive and therapeutic interventions defined in the first and second steps of therapy, depending on the gingival and periodontal status of the patient's dentition. This step should be rendered at regular intervals according to the patient's needs, and in any of these recall visits, any patient may need re‐treatment if recurrent disease is detected, and in these situations, a proper diagnosis and treatment plan should be reinstituted. In addition, compliance with the recommended oral hygiene regimens and healthy lifestyles are part of supportive periodontal care.

In any of the steps of therapy, tooth extraction may be considered if the affected teeth are considered with a hopeless prognosis.

The first part of this document was prepared by the steering group with the help of the methodology consultants, and it was carefully examined by the experts participating in the consensus and was voted upon in the initial plenary session to form the basis for the specific recommendations.

Strength of consensus strong consensus (0% of the group abstained due to potential CoI).

5. CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS: FIRST STEP OF THERAPY

The first step of therapy is aimed at providing the periodontitis patient with the adequate preventive and health promotion tools to facilitate his/her compliance with the prescribed therapy and the assurance of adequate outcomes. This step not only includes the implementation of patient's motivation and behavioural changes to achieve adequate self‐performed oral hygiene practices, but also the control of local and systemic modifiable risk factors that significantly influence this disease. Although this first step of therapy is insufficient to treat a periodontitis patient, it represents the foundation for optimal treatment response and long‐term stable outcomes.

This first step includes not only the educational and preventive interventions aimed to control gingival inflammation but also the professional mechanical removal of the supragingival plaque and calculus, together with the elimination local retentive factors.

5.1. Intervention: Supragingival dental biofilm control (by the patient)

R1.1 What are the adequate oral hygiene practices of periodontitis patients in the different steps of periodontitis therapy?

| Expert consensus‐based recommendation (1.1) |

|---|

| We recommend that the same guidance on oral hygiene practices to control gingival inflammation is enforced throughout all the steps of periodontal therapy including supportive periodontal care. |

| Supporting literature Van der Weijden and Slot (2015) |

| Grade of recommendation Grade A—↑↑ |

| Strength of consensus Strong consensus [3.8% of the group abstained due to potential conflict of interest (CoI)] |

Background

Intervention

Supragingival dental biofilm control can be achieved by mechanical and chemical means. Mechanical plaque control is mainly performed by tooth brushing, either with manual or powered toothbrushes or with supplemental interdental cleaning using dental floss, interdental brushes, oral irrigators, wood sticks, etc. As adjuncts to mechanical plaque control, antiseptic agents, delivered in different formats, such as dentifrices and mouth rinses have been recommended. Furthermore, other agents aimed to reduce gingival inflammation have also been used adjunctively to mechanical biofilm control, such as probiotics, anti‐inflammatory agents and antioxidant micronutrients.

Available evidence

Even though oral hygiene interventions and other preventive measurements for gingivitis control were not specifically addressed in the systematic reviews prepared for this Workshop to Develop Guidelines for the treatment of periodontitis, evidence can be drawn from the XI European Workshop in Periodontology (2014) (Chapple et al., 2015) and the systematic review on oral hygiene practices for the prevention and treatment of gingivitis (Van der Weijden & Slot, 2015). This available evidence supports the following:

Professional oral hygiene instructions (OHI) should be provided to reduce plaque and gingivitis. Re‐enforcement of OHI may provide additional benefits.

Manual or power tooth brushing are recommended as a primary means of reducing plaque and gingivitis. The benefits of tooth brushing out‐weigh any potential risks.

When gingival inflammation is present, inter‐dental cleaning, preferably with interdental brushes (IDBs) should be professionally taught to patients. Clinicians may suggest other inter‐dental cleaning devices/methods when the use of IDBs is not appropriate.

R1.2 Are additional strategies in motivation useful?

| Expert consensus‐based recommendation (1.2) |

|---|

| We recommend emphasizing the importance of oral hygiene and engaging the periodontitis patient in behavioural change for oral hygiene improvement. |

| Supporting literature Carra et al. (2020) |

| Grade of recommendation Grade A—↑↑ |

| Strength of consensus Strong consensus (1.3% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

Background

Intervention

Oral hygiene instructions (OHI) and patient motivation in oral hygiene practices should be an integral part of the patient management during all stages of periodontal treatment (Tonetti et al., 2015). Different behavioural interventions, as well as communication and educational methods, have been proposed to improve and maintain the patient's plaque control over time (Sanz & Meyle, 2010). See additional information in the next section on “Methods of motivation.”

R1.3 Are psychological methods for motivation effective to improve the patient's compliance in oral hygiene practices?

| Evidence‐based statement (1.3) |

|---|

| To improve patient's behaviour towards compliance with oral hygiene practices, psychological methods such as motivational interviewing or cognitive behavioural therapy have not shown a significant impact. |

| Supporting literature Carra et al. (2020) |

| Quality of evidence Five randomized clinical trials (RCTs) (1716 subjects) with duration ≥6 months in untreated periodontitis patients [(4 RCTs with high and 1 RCT with low risk of bias (RoB)] |

| Grade of recommendation Statement—unclear, additional research needed |

| Strength of consensus Strong consensus (1.3% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

Background

Intervention

Several different psychological interventions based on social cognitive theories, behavioural principles and motivational interviewing (MI) have been applied to improve OHI adherence in patients with periodontal diseases. The available evidence has not demonstrated that these psychological interventions based on cognitive constructs and motivational interviewing principles provided by oral health professionals have improved the patient's oral hygiene performance as measured by the reduction of plaque and bleeding scores over time.

Available evidence

The evidence includes two RCTs on MI (199 patients) and three RCTs on psychological interventions based on social cognitive theories and feedback (1,517 patients).

Risk of bias

The overall body of evidence was assessed at high risk of bias (four RCTs high and one RCT low).

Consistency

The majority of the studies found no significant additional benefit implementing psychological interventions in conjunction with OHI.

Clinical relevance and effect size

The reported effect size was not considered clinically relevant.

Balance of benefit and harm

Benefit and harm were not reported, and due to the fact that different health professionals were involved to provide interventions, no conclusion could be drawn.

Economic considerations

These studies did not assess a cost–benefit evaluation in spite of the expected additional cost related to the psychological intervention.

Patient preferences

No proper information was available to assess this issue.

Applicability

A psychological approach needs special training to be effectively performed.

5.2. Intervention: Adjunctive therapies for gingival inflammation

Adjunctive therapies for gingival inflammation have been considered within the adjunctive therapies to subgingival debridement, and therefore, they have been evaluated within the second step of therapy.

5.3. Intervention: Supragingival dental biofilm control (professional)

R1.4 What is the efficacy of supragingival professional mechanical plaque removal (PMPR) and control of retentive factors in periodontitis therapy?

| Expert consensus‐based recommendation (1.4) |

|---|

| We recommend supragingival professional mechanical plaque removal (PMPR) and control of retentive factors, as part of the first step of therapy. |

| Supporting literature Needleman, Nibali, and Di Iorio (2015); Trombelli, Franceschetti, and Farina (2015) |

| Grade of recommendation Grade A—↑↑ |

| Strength of consensus Unanimous consensus (0% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

Background

Intervention

The removal of the supragingival dental biofilm and calcified deposits (calculus) (here identified under the term “professional mechanical plaque removal” (PMPR)) is considered an essential component in the primary (Chapple et al., 2018) and secondary (Sanz et al., 2015) prevention of periodontitis as well as within the basic treatment of plaque‐induced periodontal diseases (van der Weijden & Slot, 2011). Since the presence of retentive factors, either associated with the tooth anatomy or more frequently, due to inadequate restorative margins, are often associated with gingival inflammation and/or periodontal attachment loss, they should be prevented/eliminated to reduce their impact on periodontal health.

Available evidence

Even though these interventions were not specifically addressed in the systematic reviews prepared for this Workshop to develop guidelines for the treatment of periodontitis, indirect evidence can be found in the 2014 European Workshop on Prevention, in which the role of PMPR was addressed both in primary prevention (Needleman et al., 2015) or in supportive periodontal care (SPC) (Trombelli et al., 2015). Some additional evidence can be found to support both procedures, as part of periodontitis therapy. A split‐mouth RCT, with a follow‐up of 450 days in 25 subjects, concluded that the performance of supragingival debridement, before subgingival debridement, decreased subgingival treatment needs and maintained the periodontal stability over time (Gomes, Romagna, Rossi, Corvello, & Angst, 2014). In addition, supragingival debridement may induce beneficial changes in the subgingival microbiota (Ximénez‐Fyvie et al., 2000). Moreover, it has been established that retentive factors may increase the risk of worsening the periodontal condition (Broadbent, Williams, Thomson, & Williams, 2006; Demarco et al., 2013; Lang, Kiel, & Anderhalden, 1983).

5.4. Intervention: Risk factor control

5.4.1. R1.5 What is the efficacy of risk factor control in periodontitis therapy?

| Evidence‐based recommendation (1.5) |

|---|

| We recommend risk factor control interventions in periodontitis patients, as part of the first step of therapy. |

| Supporting literature Ramseier et al. (2020) |

| Quality of evidence 25 clinical studies |

| Grade of recommendation Grade A—↑↑ |

| Strength of consensus Strong consensus (1.3% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

Background

Intervention

Smoking and diabetes are two proven risk factors in the etiopathogenesis of periodontitis (Papapanou et al., 2018), and therefore, their control should be an integral component in the treatment of these patients. Interventions for risk factor control have aimed to educate and advice patients for behavioural change aimed to reduce them and in specific cases to refer them for adequate medical therapy. Other relevant factors associated with healthy lifestyles (stress reduction, dietary counselling, weight loss or increased physical activities) may also be part of the overall strategy for reducing patient's risk factors.

Available evidence

In the systematic review (Ramseier et al., 2020), the authors have identified 13 relevant guidelines for interventions for tobacco smoking cessation, promotion of diabetes control, physical exercise (activity), change of diet, carbohydrate (dietary sugar reduction) and weight loss. In addition, 25 clinical studies were found that assess the impact of (some of) these interventions in gingivitis/periodontitis patients.

Risk of bias

It is explained specifically for each intervention.

Consistency

The heterogeneity in study design precludes more consistent findings, but adequate consistency may be found for studies on smoking cessation and diabetes control.

Clinical relevance and effect size

No meta‐analysis was performed; effect sizes can be found in the individual studies.

Balance of benefit and harm

In addition to periodontal benefits, all the tested interventions represent a relevant beneficial health impact.

Economic considerations

The various studies do not indicate a cost–benefit evaluation. However, it cannot be discarded an additional cost related to the psychological intervention. However, the systemic health benefits that can be obtained from these interventions, if they are successful, would represent reduced cost of healthcare services in different comorbidities.

Patient preferences

Interventions are heterogeneous, but the potential systemic health benefits may favour preference for them.

Applicability

Demonstrated with studies testing large groups from the general population; the practicality of routine use is still to be demonstrated.

R1.6 What is the efficacy of tobacco smoking cessation interventions in periodontitis therapy?

| Evidence‐based recommendation (1.6) |

|---|

| We recommend tobacco smoking cessation interventions to be implemented in patients undergoing periodontitis therapy. |

| Supporting literature Ramseier et al. (2020) |

| Quality of evidence Six prospective studies with, at least, 6‐month follow‐up |

| Grade of recommendation Grade A—↑↑ |

| Strength of consensus Unanimous consensus (1.2% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

Background

Intervention

Periodontitis patients may benefit from smoking cessation interventions to improve periodontal treatment outcomes and the maintenance of periodontal stability. Interventions consist of brief counselling and may include patient referral for advanced counselling and pharmacotherapy.

Available evidence

In the systematic review (Ramseier et al., 2020), six prospective studies of 6‐ to 24‐month duration and performed at university setting were identified. Different interventions were tested (smoking cessation counselling, 5 A's [ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange], cognitive behavioural therapy [CBT], motivational interview, brief interventions, nicotine replacement therapies). In three of the studies, the intervention was programmed in parallel with non‐surgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) and followed by SPC, in one study SPC patients were included and, in another, patients in NSPT and in SPC were compared; in one study, it was unclear. The success of smoking cessation was considered as moderate (4%–30% after 1–2 years), except in one study. Two studies demonstrated benefits in periodontal outcomes, when comparing former smokers to smokers and oscillators.

Additional factors have been discussed in the overall evaluation of risk factor control.

R1.7 What is the efficacy of promotion of diabetes control interventions in periodontitis therapy?

| Evidence‐based recommendation (1.7) |

|---|

| We recommend diabetes control interventions in patients undergoing periodontitis therapy. |

| Supporting literature Ramseier et al. (2020) |

| Quality of evidence Two 6‐month RCTs |

| Grade of recommendation Grade A—↑↑ |

| Strength of consensus Consensus (0% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

Background

Intervention

Periodontitis patients may benefit from diabetes control interventions to improve periodontal treatment outcomes and the maintenance of periodontal stability. These interventions consist of patient education as well as brief dietary counselling and, in situations of hyperglycaemia, the patient's referral for glycaemic control.

Available evidence

In the systematic review (Ramseier et al., 2020), two studies on the impact of diabetes control interventions in periodontitis patients were identified, two of them 6‐month RCTs, all of them performed at university settings. Periodontal interventions were not clearly defined. Different interventions were tested, including individual lifestyle counselling, dietary changes and oral health education. Some improvements were observed in the intervention groups, in terms of periodontal outcomes.

Additional factors have been discussed in the overall evaluation of risk factor control.

R1.8 What is the efficacy of increasing physical exercise (activity) in periodontitis therapy?

| Evidence‐based recommendation (1.8) |

|---|

| We do not know whether interventions aimed to increasing the physical exercise (activity) have a positive impact in periodontitis therapy. |

| Supporting literature Ramseier et al. (2020) |

| Quality of evidence One 12‐week RCT, one 12‐week prospective study |

| Grade of recommendation Grade 0—Statement: unclear, additional research needed |

| Strength of consensus Consensus (0% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

Background

Intervention

Overall evidence from the medical literature suggests that the promotion of physical exercise (activity) interventions may improve both treatment and the long‐term management of chronic non‐communicable diseases. In periodontitis patients, the promotion may consist of patient education and counselling tailored to the patients' age and general health.

Available evidence

In the systematic review (Ramseier et al., 2020), two 12‐week studies on the impact of physical exercise (activity) interventions in periodontitis patients were identified, one RCT (testing education with comprehensive yogic interventions followed by yoga exercises) and one prospective study (with briefing followed by physical exercises; the control group was a dietary intervention), performed at university settings. Periodontal interventions were not clearly defined, although in the yoga study, standard therapy was delivered (by not described) in periodontitis patients, while no periodontal therapy was provided in the second study. Both studies reported improved periodontal parameters, including bleeding scores and probing depth changes, after 12 weeks (although in the yoga study also, the influence on psychological stress could not be discarded).

Additional factors have been discussed in the overall evaluation of risk factor control.

R1.9 What is the efficacy of dietary counselling in periodontitis therapy?

| Evidence‐based recommendation (1.9) |

|---|

| We do not know whether dietary counselling may have a positive impact in periodontitis therapy. |

| Supporting literature Ramseier et al. (2020) |

| Quality of evidence Three RCTs, four prospective studies |

| Grade of recommendation Grade 0—Statement: unclear, additional research needed |

| Strength of consensus Consensus (0% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

Background

Intervention

Periodontitis patients may benefit from dietary counselling interventions to improve periodontal treatment outcomes and the maintenance of periodontal stability. These interventions may consist of patient education including brief dietary advices and in specific cases patient's referral to a nutrition specialist.

Available evidence

In the systematic review (Ramseier et al., 2020), seven studies on the impact of dietary counselling (mainly addressing lower fat intake, less free sugars and salt intake, increase in fruit and vegetable intake) in periodontitis (with or without other comorbidities) patients were identified: three RCTs (6 months, 8 weeks, 4 weeks) and four prospective studies (12 months, 24 weeks, 12 weeks, 4 weeks), performed at hospital and university settings. Periodontal interventions were not clearly defined, although in the 6‐month RCT, periodontal treatment was part of the protocol. Some studies showed significant improvements in periodontal parameters, but the RCT with the longest follow‐up was not able to identify significant benefits (Zare Javid, Seal, Heasman, & Moynihan, 2014).

In the systematic review (Ramseier et al., 2020), two studies specifically on the impact of dietary counselling aiming at carbohydrate (free sugars) reduction in gingivitis/periodontitis patients were identified, one 4‐week RCT (including also gingivitis patients) and one 24‐week prospective study. Periodontal interventions were not clearly defined. Both studies reported improved gingival indices.

Additional factors have been discussed in the overall evaluation of risk factor control.

5.4.2. What is the efficacy of lifestyle modifications aiming at weight loss in periodontitis therapy?

| Evidence‐based recommendation (1.10) |

|---|

| We do not know whether interventions aimed to weight loss through lifestyle modification may have a positive impact in periodontitis therapy. |

| Supporting literature Ramseier et al. (2020) |

| Quality of evidence Five prospective studies |

| Grade of recommendation Grade 0—Statement: unclear, additional research needed |

| Strength of consensus Strong consensus (0% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

5.4.3. Background

Intervention

Available evidence suggests that weight loss interventions may improve both the treatment and long‐term outcome of chronic non‐communicable diseases. In periodontitis patients, these interventions may consist of specific educational messages tailored to the patients' age and general health. These should be supported with positive behavioural change towards healthier diets and increase in physical activity (exercise).

Available evidence

In the systematic review (Ramseier et al., 2020), five prospective studies, in obese gingivitis/periodontitis patients, on the impact of weight loss interventions were identified, with different follow‐ups (18 months, 12 months, 24 weeks and two studies of 12 weeks). Periodontal interventions were not clearly defined. Intensity of lifestyle modifications aiming at weight loss interventions ranged from a briefing, followed by counselling in dietary change, to an 8‐week high‐fibre, low‐fat diet, or a weight reduction programme with diet and exercise‐related lifestyle modifications. Three studies reported beneficial periodontal outcomes and, the other two, no differences.

Additional factors have been discussed in the overall evaluation of risk factor control.

6. CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS: SECOND STEP OF THERAPY

The second step of therapy (also known as cause‐related therapy) is aimed at the elimination (reduction) of the subgingival biofilm and calculus and may be associated with removal of root surface (cementum). The procedures aimed at these objectives have received in the scientific literature different names: subgingival debridement, subgingival scaling, root planning, etc. (Kieser, 1994). In this guideline, we have agreed to use the term “subgingival instrumentation” to all non‐surgical procedures, either performed with hand (i.e. curettes) or power‐driven (i.e. sonic/ultrasonic devices) instruments specifically designed to gain access to the root surfaces in the subgingival environment and to remove subgingival biofilm and calculus. This second step of therapy requires the successful implementation of the measures described in the first step of therapy.

Furthermore, subgingival instrumentation may be supplemented with the following adjunctive interventions:

Use of adjunctive physical or chemical agents.

Use of adjunctive host‐modulating agents (local or systemic).

Use of adjunctive subgingival locally delivered antimicrobials.

Use of adjunctive systemic antimicrobials.

6.1. Intervention: Subgingival instrumentation

R2.1 Is subgingival instrumentation beneficial for the treatment of periodontitis?

| Evidence‐based recommendation (2.1) |

|---|

| We recommend that subgingival instrumentation be employed to treat periodontitis in order to reduce probing pocket depths, gingival inflammation and the number of diseased sites. |

| Supporting literature Suvan et al. (2019) |

| Quality of evidence One 3‐month RCT (n = 169 patients); 11 prospective studies (n = 258) ≥6 months |

| Grade of recommendation Grade A—↑↑ |

| Strength of consensus Unanimous consensus (2.6% of the group abstained due to potential CoI) |

Background

Intervention