Abstract

Cationic, amphipathic, α‐helical host‐defense peptides (HDPs) that are naturally secreted by certain species of frogs (Anura) possess potent broad‐spectrum antimicrobial activity and show therapeutic potential as alternatives to treat infections by multidrug‐resistant pathogens. Fourteen amphibian skin peptides and twelve analogues of temporin‐1DRa were studied for their antimicrobial activities against clinically relevant human or animal skin infection‐associated pathogens. For comparison, antimicrobial potencies of frog skin peptides against a range of probiotic lactobacilli were determined. We used the VITEK 2 system to define a profile of antibiotic susceptibility for the bacterial panel. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of the naturally occurring temporin‐1DRa, CPF‐AM1, alyteserin‐1c, hymenochirin‐2B, and hymenochirin‐4B for pathogenic bacteria were threefold to ninefold lower than the values for the tested probiotic strains. Similarly, temporin‐1DRa and its [Lys4], [Lys5], and [Aib8] analogues showed fivefold to 6.5‐fold greater potency against the pathogens. In the case of PGLa‐AM1, XT‐7, temporin‐1DRa and its [D‐Lys8] and [Aib13] analogues, no apoptosis or necrosis was detected in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells at concentrations below or above the MIC. Given the differential activity against commensal bacteria and pathogens, some of these peptides are promising candidates for further development into therapeutics for topical treatment of skin infections.

Keywords: antimicrobial peptide, biological screening, HDP

With the aim of identifying antimicrobial peptides that could be further investigated as topical treatments for human or animal skin infections, we determined the MIC values of 14 naturally occurring amphibian peptides and 12 analogues of temporin‐1DRa against clinically relevant pathogens as well as probiotic lactobacilli. Results showed several promising peptide candidates for topical treatment of human or animal skin infections, given the differential activity against commensal bacteria and pathogens.

1. INTRODUCTION

The alarming increase in incidence of multidrug‐resistant (MDR), pathogenic bacteria together with the decreasing discovery rates for new antibiotics represents a major societal problem and threat to human and animal health. This situation has heightened interest in naturally occurring host‐defense peptides (HDPs), including antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), as potential novel therapeutics (Afacan, Yeung, Pena, & Hancock, 2012; Mangoni, McDermott, & Zasloff, 2016). A widely studied class of HDPs is cationic amphipathic α‐helical peptides, many of which are originally isolated from skin secretions of species belonging to the Anura order of amphibians (frogs and toads). Amphibians are, for a large part of their lifecycle, confined to warm and moist environments with high exposure to bacteria and fungi. However, frogs and toads possess excellent immunity to defend themselves against invasion by micro‐organisms. It is currently believed that as part of their innate immune system many species, but not all, produce and secrete a wide variety of HDPs via specialized glands in the skin (Conlon, 7,b; Konig, Bininda‐Emonds, & Shaw, 2015). Amphibian peptides were among the first HDPs described nearly three decades ago (Giovannini, Poulter, Gibson, & Williams, 1987; Zasloff, 1987), and they form a highly diverse group of peptides comprising between 8 and 48 amino acid residues and generally a net charge between +2 and +6 at pH 7 (Wang, Li, & Wang, 2015). Production of amphibian skin peptides seems to be evolutionarily conserved, presumably due to their role in preventing infection by pathogenic microbes, although some skin peptides may also have autocrine or chemotactic functions (Conlon, 7,b; Konig et al., 2015). Previously, certain frog skin peptides have been proposed as candidates to treat infections on the basis of their potent and broad‐range antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria, fungi, and protozoa (Conlon & Mechkarska, 2014; Yeung, Gellatly, & Hancock, 2011).

A disadvantage of many of these candidate HDPs in a therapeutic setting is their hemolytic activity and cytotoxicity, although this is typically observed at concentrations significantly higher than the minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC). However, it is possible to selectively reduce the cytotoxicity of HDPs through systematic amino acid substitutions to alter physiochemical properties, while retaining their potency and broad‐spectrum antimicrobial activity (Conlon, Al‐Ghaferi, Abraham, & Leprince, 2007; Conlon, Al‐Kharrge et al., 2007). For the above‐mentioned reasons, HDPs currently show most promise as topical treatments for skin and wound infections rather than for systemic applications to treat invasive disease (Conlon & Mechkarska, 2014; Mangoni et al., 2016; Ong et al., 2002).

The aim of this study was to test a range of amphibian skin peptides and analogues of temporin‐1DRa with different physicochemical properties in antimicrobial assays. We determined their effect on a selection of pathogens including opportunistic bacteria isolated from human or animal skin infections and MDR strains. We included several probiotic, commensal strains in the assays to investigate the spectrum of activity and selectivity of the amphibian HDPs. To benchmark the efficacy of these skin peptides, we also determined susceptibility of the selected bacteria to commonly used antibiotics using an ISO‐certified assay platform.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Bacteria and culture conditions

Table 1 lists the bacterial strains used in this study and their source. Nine probiotic Lactobacilli were previously isolated from commercially available products (Meijerink et al., 2012); Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 is a single colony isolated from L. plantarum NCIMB8826, which was originally derived from human saliva (Hayward, 1956). Lactobacillus casei Shirota (Yakult®) was originally isolated from the human intestine, and Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC55730 was originally isolated from human breast milk (Casas & Mollstam, 1998). Streptococcus suis S10 (Vecht, Wisselink, van Dijk, & Smith, 1992) was obtained from the Central Veterinary Institute (CVI, Lelystad); Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (strains 26228 and 25467) were isolated from skin infections in dogs and were obtained from University of Copenhagen (KU). The Enterococcus faecium,Staphylococcus aureus,Acinetobacter baumannii, and P. aeruginosa strains MDR1 and MDR2 were isolated from clinical samples and were obtained from the Erasmus University Medical Centre Rotterdam (EMC). Lactobacilli were cultured and assayed in de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) broth (VWR International) at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. All other strains were cultured in Müller–Hinton (MH) broth (Oxoid Ltd) at 37°C under aerobic conditions.

Table 1.

Bacteria used in this study

| Bacterial species | Strain | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commensal/probiotic | Lactobacillus plantarum | WCFS1 | TIFN |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | LGG | Valio | |

| Lactobacillus salivarius subsp. salicinius | DSM20554 | DSMZ | |

| Lactobacillus salivarius | FortaFit Ls‐33 | Danisco | |

| Lactobacillus casei | R0215 | Rossell | |

| Lactobacillus casei | Shirota | Yakult | |

| Lactobacillus johnsonii | LC‐1 | Nestle | |

| Lactobacillus reuteri | ATCC55730 | BioGaia | |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | LA5 | Chr Hansen | |

| Pathogenic/opportunistic | Streptococcus suis | S10 3881 | CVI (Vecht et al., 1992) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | DMS 20231 | DSMZ | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Sens 8325.4 | EMC | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | MRSA B33424 | EMC | |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius | E138 | KU | |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius | E139 | KU | |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius | E140 | KU | |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius | S70E2 | KU | |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius | S70E8 | KU | |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius | S70F3 | KU | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 26228 | KU | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 25467 | KU | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Sens1 PA01 | EMC | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Sens2 ATCC27853 | EMC | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MDR1 B38084 | EMC | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MDR2 B31770 | EMC | |

| Enterococcus faecium | Sens S1 | EMC | |

| Enterococcus faecium | Sens S2 | EMC | |

| Enterococcus faecium | VanA R39 | EMC | |

| Enterococcus faecium | VanB R44 | EMC | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | MDR Bangl 027 | EMC |

2.2. Bacterial antibiotic susceptibility testing

The profile of antibiotic susceptibility of a panel of bacterial isolates was determined by the microbroth dilution test using the ISO‐certified VITEK® 2 system (bioMérieux Benelux BV; Funke, Monnet, deBernardis, von Graevenitz, & Freney, 1998; Garcia‐Garrote, Cercenado, & Bouza, 2000). The following antibiotic cards were used: AST‐P633 (cefoxitin, benzylpenicillin, oxacillin, gentamicin, kanamycin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, linezolid, teicoplanin, vancomycin, tetracycline, fosfomycin, fusidic acid, mupirocin, chloramphenicol, rifampicin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole), AST‐N199 (piperacillin/tazobactam, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, gentamicin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, colistin), and AST‐P586 (ampicillin, sulbactam, cefuroxime, cefuroxime axetil, imipenem, gentamycin, streptomycin, moxifloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, quinupristin/dalfopristin, linezolid, teicoplanin, vancomycin, tetracycline, tigecycline, nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole). Bacteria were inoculated from glycerol stocks on appropriate growth medium agar plates using sterile plastic loops and incubated at 37°C overnight, after which single colonies were picked for analysis.

2.3. Peptides

The frog skin peptides and the temporin‐1DRa analogues (Table 2) used in this study were chemically synthesized and purified as previously described (Al‐Ghaferi et al., 2010; Ali, Soto, Knoop, & Conlon, 2001; Conlon et al., 2006; Conlon, Al‐Ghaferi, et al. 2007; Conlon, Al‐Kharrge et al., 2007; Conlon et al., 2009; Conlon et al., 2010; Mechkarska, Prajeep et al., 2012, Mechkarska, Meetani et al., 2012; Olson III, Soto, Knoop, & Conlon, 2001). The identities of all peptides were confirmed by electrospray mass spectrometry, and their purity was >98%. Lyophilized peptides were reconstituted in 20 μl 0.1% HCl, and stock solutions were made at 1 or 2.5 mg/ml in sterile PBS and kept at −20°C until use.

Table 2.

The naturally occurring peptides and temporin‐1DRa analogues used in this study and their source species

| Source/Peptide | Length | Amino acid sequence | Net charge | GRAVY | α‐helicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pipidae | |||||

| 1.1. Xenopus | |||||

| 1.1.1. Xenopus amieti | |||||

| Magainin‐AM1 | 23 aa | GIKEFAHSLGKFGKAFVGGILNQ | +2 | +0.2 | Non‐helical |

| PGLa‐AM1 | 22 aa | GMASKAGSVLGKVAKVALKAAL.NH2 | +4 | +0.83 | 9–22 |

| CPF‐AM1 | 17 aa | GLGSVLGKALKIGANLL.NH2 | +2 | +1.03 | 5–14 |

| 1.1.2. X. laevis × X. muelleri | |||||

| PGLa‐LM1 | 21 aa | GMASKAGSVAGKIAKFALGAL.NH2 | +4 | +0.805 | 9–18 |

| 1.2. Silurana | |||||

| 1.2.1. Silurana tropicalis | |||||

| XT‐7 (CPF‐ST3) | 18 aa | GLLGPLLKIAAKVGSNLL.NH2 | +2 | +1.12 | 5–13 |

| 1.3. Hymenochirus | |||||

| 1.3.1. Hymenochirus boettgeri | |||||

| Hymenochirin‐1B | 29 aa | IKLSPETKDNLKKVLKGAIKGAIAVAKMV.NH2 | +6 | +0.169 | 5–27 |

| Hymenochirin‐2B | 29 aa | LKIPGFVKDTLKKVAKGIFSAVAGAMTPS | +4 | +0.466 | 8–16 |

| Hymenochirin‐4B | 28 aa | IKIPAFVKDTLKKVAKGVISAVAGALTQ | +4 | +0.664 | 7–16 |

| 2. Alytidae | |||||

| 2.1. Alytes | |||||

| 2.1.1. Alytes obstetricans | |||||

| Alyteserin‐1c | 23 aa | GLKEIFKAGLGSLVKGIAAHVAS.NH2 | +3 | +0.748 | 2–8; 10–21 |

| Alyteserin‐2a | 16 aa | ILGKLLSTAAGLLSNL.NH2 | +2 | +1.275 | 9–14 |

| 3. Ranidae | |||||

| 3.1. Rana | |||||

| 3.1.1. Rana draytonii | |||||

| Temporin‐1DRa | 14 aa | HFLGTLVNLAKKIL.NH2 | +3 | +0.879 | 5–14 |

| [Lys4]temporin‐1DRa | HFLKTLVNLAKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | 4–14 | |

| [Lys5]temporin‐1DRa | HFLGKLVNLAKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | 4–14 | |

| [D‐Lys4]temporin‐1DRa | HFLkTLVNLAKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | nd | |

| [D‐Lys5]temporin‐1DRa | HFLGkLVNLAKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | nd | |

| [D‐Lys8]temporin‐1DRa | HFLGTLVkLAKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | nd | |

| [Aib8]temporin‐1DRa | HFLGTLV[Aib]LAKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | 5–14 | |

| [Aib9]temporin‐1DRa | HFLGTLVN[Aib]AKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | 5–14 | |

| [Aib10]temporin‐1DRa | HFLGTLVNL[Aib]KKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | 5–14 | |

| [Aib13]temporin‐1DRa | HFLGTLVNLAKK[Aib]L.NH2 | +4 | nd | 5–14 | |

| [Orn7]temporin‐1DRa | HFLGTL[Orn]NLAKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | nd | |

| [DAB7] temporin‐1DRa | HFLGTL[DAB]NLAKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | nd | |

| [TML7] temporin‐1DRa | HFLGTL[TML]NLAKKIL.NH2 | +4 | nd | nd | |

| 3.1.2. Rana boylii | |||||

| Brevinin‐1BYa | 24 aa | FLPILASLAAKFGPKLFCLVTKKC | +4 | +1.07 | 4–12 |

| 3.2. Hylarana | |||||

| 3.2.1. Hylarana erythraea | |||||

| B2RP‐Era | 19 aa | GVIKSVLKGVAKTVALGML.NH2 | +3 | +1.25 | 13–16 weak |

| 4. Hylidae | |||||

| 4.1. Pseudis | |||||

| 4.1.1 Pseudis paradoxa | |||||

| Pseudin‐2 | 24 aa | GLNALKKVFQGIHEAIKLINNHVQ.NH2 | +3 | −0.008 | 2–19; 14–19 |

PGLa‐LM1 was found in a hybrid frog of X. laevis and X. muelleri (1.1.2) (Mechkarska, Meetani et al., 2012). Single amino acid residue substitutions are marked in bold font. The net charge is calculated at pH 7.0. The grand average of hydropathy (GRAVY) is defined as the sum of all hydropathy values divided by the length of the sequence (Kyte & Doolittle, 1982). AGADIR (Munoz & Serrano, 1994) was used to predict which residues of the peptide are in an α‐helical confirmation. Aib, α‐aminoisobutyric acid; Orn, ornithine; DAB, diaminobutyric acid; TML, trimethyllysine; nd, not determined.

2.4. Antimicrobial assays

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the peptides were determined by standard dilution assays in 96‐well microtiter plates in two independent experiments (Institute CLaS, 2008). Serial dilutions of peptide in the appropriate growth medium (25 μl) were mixed with bacterial suspension (75 μl) to obtain an inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/ml. Bacteria were incubated at 37°C for 18–22 hr, after which bacterial growth was measured by absorption at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer (Spectramax M5; Molecular Devices). The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration at which no visible growth was observed. MBC was determined as the lowest concentration of peptide at which no viable bacteria could be detected, following plating of serial dilutions of suspensions from the wells on agar plates. Heatmaps were generated using the Multiple Experiment Viewer software (Saeed et al., 2003), using Euclidean distance with average linkage for hierarchical clustering of the data.

2.5. Human peripheral blood mononuclear monocyte (PBMC) cytotoxicity assay

Human peripheral blood mononuclear monocytes were isolated as previously described (van Hemert et al., 2010) with modifications. Buffy coats from peripheral blood of three healthy donors were obtained from the Sanquin Blood Bank, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Isolated PBMCs were washed and resuspended in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) + Glutamax (Gibco, Thermo Fischer Scientific) supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml and seeded (100 μl per well) in 96‐well tissue culture plates. PBMCs were exposed to peptides at final concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 μg/ml. Exposure to LPS (1 μg/ml) was used as a positive control, and cells with only IMDM served as negative control. After exposure for 24 hr, cells were incubated with Annexin V‐APC and propidium iodide (eBiosciences), and using flow cytometry (FACS Canto II, BD Biosciences), the proportions of live (unstained), dead (PI only), early‐apoptotic (Annexin V only), and late‐apoptotic (Annexin V + PI) cells were determined (BD FACSDiva). Data are presented as mean values ±SD.

3. RESULTS

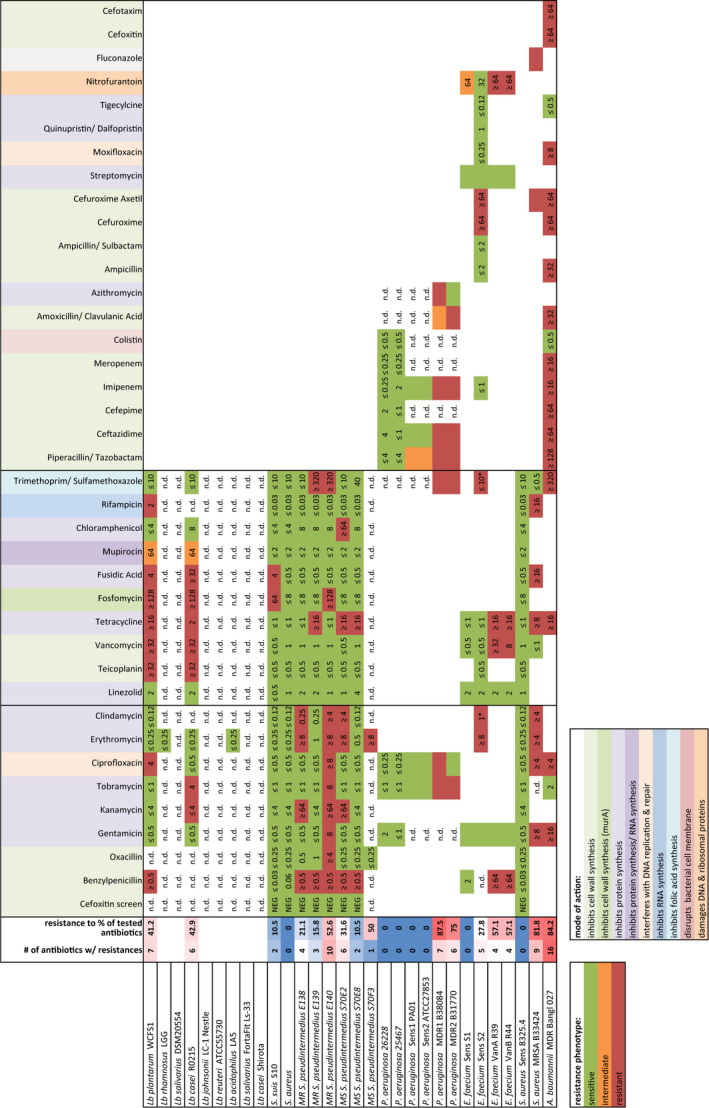

3.1. Antibiotic resistance of a panel of selected probiotic and pathogenic microbes

We used the bioMerieux VITEK®2 system to assay microbial resistance to commonly used antibiotics (EUCAST, 2014) for which the mode of action and bacterial target is given in Table S1. The VITEK®2 system was chosen as it represents a widely used and well‐standardized ISO‐certified platform used in hospitals and medical centers to assess antibiotic resistance of clinically sampled microbes. As many Lactobacillus species did not grow under the VITEK®2 incubation conditions, their antibiotic susceptibility profile is not provided. The data for antibiotic resistance of each bacterium (Table 3) were used for benchmarking against each of the frog antimicrobial peptides. In the first row, the number of antibiotics to which a strain was resistant is depicted by a color scheme: Brighter red colors correspond to increased antibiotic resistance, and brighter blue correspond to increased susceptibility to the tested antibiotics (Table 3). These data provide the baseline resistance of a selected set of bacteria to antibiotics, classifying certain strains as multidrug resistant (MDR). The reference dataset of antibiotic resistance was compared to a dataset of the MIC and MBC values for frog antimicrobial peptides and synthetic analogues tested against the same strains.

Table 3.

Antibiotic resistance profile for bacteria used in this study, as determined by the VITEK®2 system

|

|

Multiple antibiotics cards were used, differing in antibiotics depending on the target species. Profiles for those lactobacilli requiring anaerobic culture conditions were not obtained. Resistance phenotype per antibiotic was scored as sensitive (green), intermediate (orange), or resistant (red) according to the EUCAST species‐specific breakoff points based on MIC values (EUCAST, 2014). A summary of antibiotic resistance for each strain is provided in the second column, shaded from resistance to no resistance (dark blue) to resistance to 16 antibiotics (dark red). See Table S1 for an overview of mode of actions of each antibiotic. nd, not determined.

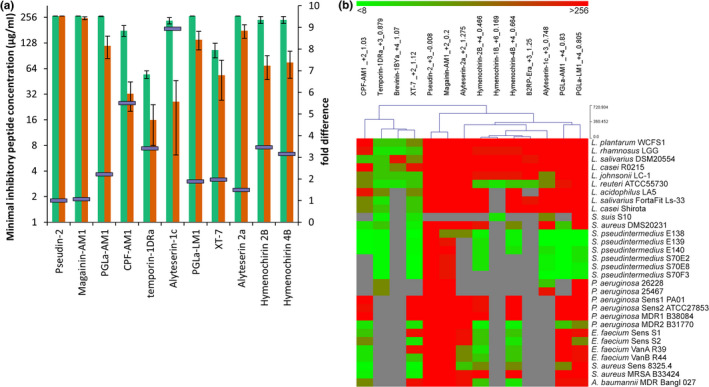

3.2. Potency of frog skin peptides against probiotic and pathogenic microbes

Twelve frog skin peptides were tested for their antimicrobial activity against a panel of bacteria. Antimicrobial activities were determined using a standard microbroth dilution assay and are presented as MIC (Figure 1b) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC; Table S2). Figure 1b represents the MIC values obtained for the naturally occurring frog skin peptides as a hierarchically clustered heatmap, with bright green colors corresponding to values of <8 μg/ml and bright red colors corresponding to values of >256 μg/ml. The heatmap shows that temporin‐1DRa and XT‐7 were effective at low concentration (<8 μg/ml) while magainin‐AM1 and pseudin‐2 showed no inhibition of any of the strains tested. With the exception of magainin‐AM1 and pseudin‐2, all the native frog peptides tested inhibited all strains of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius at MIC = 8 μg/ml. The three hymenochirin peptides are clustered together based on the observed MIC values, showing activity against Gram‐positive MDR S. pseudintermedius, vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus faecium and the Gram‐negative MDR Acinetobacter baumannii. The PGLa peptides are also clustered together based on their low MIC against all S. pseudintermedius strains. The strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa were relatively insensitive to the frog peptides tested, except for the MDR2 isolate. For the Gram‐positive bacteria (see Table 1), we compared the MIC of selected frog peptides against 9 different species of lactobacilli (Figure 1a, green bars) and 13 pathogenic strains (excluding S. suis; Figure 1a, orange bars) and measured the fold difference in MIC value between these two bacterial groups (Figure 1a, purple bars). We found that the Gram‐positive pathogens were 5.5‐fold to ninefold more susceptible to inhibition by CPF‐AM1, temporin‐1DRa, and alyteserin‐1c than the probiotic lactobacilli.

Figure 1.

(a) Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of a selection of naturally occurring frog skin peptides against nine Gram‐positive lactic acid bacteria (green) and 13 Gram‐positive pathogenic bacteria (orange). The fold difference in MIC between the two groups is depicted as purple bars on the secondary axis. Average values ± SEM are shown. (b) Heatmap representation of all MIC values of the tested frog skin peptides, including for each peptide its net charge at pH 7 and grand average of hydropathy (GRAVY). The gray color indicates MIC was not determined

Temporin‐1DRa, a peptide, first isolated from Rana draytonii (Conlon et al., 2006), showed most promise for therapeutic activity against a range of Gram‐positive pathogens including methicillin‐resistant strains of S. pseudintermedius which are a major cause of recurring skin and wound infections in dogs (Bannoehr & Guardabassi, 2012). Additionally, the MIC values for temporin‐1DRa were ~3.5‐fold lower for pathogens than probiotic species (Figure 1a).

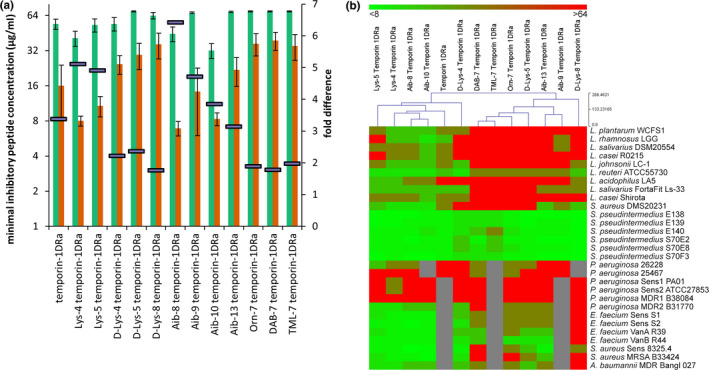

3.3. Antimicrobial activities of analogues of temporin‐1DRa

To investigate whether the antimicrobial activity of temporin‐1DRa against pathogenic species could be increased by appropriate amino acid substitutions, we tested 12 different analogues, having single residue modifications to alter parameters such as cationicity, hydrophobicity, and α‐helicity (Conlon, Al‐Ghaferi, et al., 2007; Conlon, Al‐Kharrge et al., 2007; Table 2). The effect of these amino acid substitutions on the physicochemical properties of α‐helical peptides and the subsequent effect on cytotoxicity and antimicrobial potency has been described previously (Conlon, Al‐Ghaferi, et al., 2007; Conlon, Al‐Kharrge et al., 2007). We observed MIC values that ranged from <8 to >64 μg/ml for these temporin‐1Dra analogues, although multiple isolates of the same species showed similar sensitivities to a given peptide (Figure 2; Table S3). Figure 2A Shows that the analogues had altered activity against bacteria, with [Aib8]temporin‐1DRa having the largest fold‐change (6.5) in activity between the grouped Gram‐positive pathogenic and probiotic bacteria, followed by the [Lys4], [Lys5], and [Aib9] analogues. Incorporation of α‐aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) into a peptide generally promotes the formation of an α‐ or 310‐helix or stabilizes an existing helical conformation (Karle & Balaram, 1990).

Figure 2.

(a) Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of temporin‐1DRa analogues against 9 Gram‐positive lactic acid bacteria (green) and 13 Gram‐positive pathogenic bacteria (orange). The fold difference in MIC between the two bacterial groups is depicted as purple bars on the secondary axis. Average values ± SEM are shown. (b) Heatmap representing the MIC values of temporin‐1DRa analogues against the panel of tested bacteria. The gray color indicates MIC was not determined

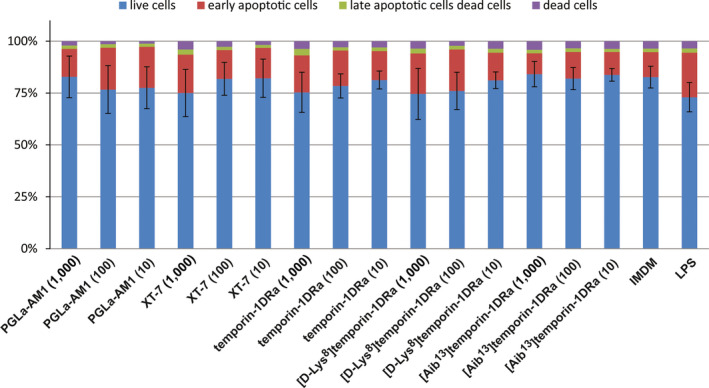

3.4. Cytotoxic effects of selected frog peptides and temporin‐1DRa analogues

In order to determine the cytotoxic activities of peptides with most potent antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria (PGLa‐AM1, XT‐7, temporin‐1DRa and its [D‐Lys8] and [Aib13] analogues, we exposed human PBMCs to the peptides and quantified apoptosis and necrosis using flow cytometry. Figure 3 shows that none of the peptides tested had a significant effect on the viability of PBMCs during a 24‐hr exposure to final peptide concentrations of 1, 10, and 1,000 μg/ml.

Figure 3.

Human PBMCs obtained from three healthy donors were exposed to 100, 10, or 1 μg/ml of PGLa‐AM1, XT‐7, temporin‐1DRa, [D‐Lys8]temporin‐1DRa, and [Aib13]temporin‐1Dra for 24 hr, stained with Annexin V and PI and apoptotic or dead cells quantified by flow cytometry. Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) was used as a negative control, and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was used as a positive control. Proportions of live (blue), early‐apoptotic (red), late‐apoptotic (green), and dead (purple) cells are displayed. Error bars depict SD of live cells between averaged values of all three donors

4. DISCUSSION

Many frogs secrete host‐defense peptides (HDPs) into the outer skin mucosa (Conlon, 7,b; Konig et al., 2015), which may have potent and broad‐range antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Consequently, HDPs are interesting candidates for antimicrobial therapeutic applications (Conlon & Mechkarska, 2014; Yeung et al., 2011). The amphipathic peptides we tested limit growth of several multidrug‐resistant Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative pathogens. We found that the Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains were relatively insensitive to the action of the peptides. This is possibly due to the secretion of extracellular proteases that aid in their resilience toward peptide antimicrobials (Engel, Hill, Caballero, Green, & O'Callaghan, 1998).

The MIC and MBC values obtained for PGLa‐AM1, PGLa‐LM1, CPF‐AM1, alyteserin‐1c, hymenochirin‐2B, and hymenochirin‐4B and the [Aib8], [Lys4], [Lys5], and [Aib9] temporin‐1DRa analogues showed promising differential activity against the pathogenic bacteria Staphylococcus pseudintermedius,Enterococcus faecium, and Acinetobacter baumannii compared to the probiotic strains of lactobacilli (Figures 1, 2). The observed differences in antimicrobial activity between tested peptides and analogues may in part be explained by the different α‐helicity and peptide stability (Conlon, Al‐Ghaferi, et al., 2007; Conlon, Al‐Kharrge et al., 2007). In a recent study, it was shown that PGLa‐AM1 and CPF‐AM1 have potent antimicrobial activity against a selection of oral pathogens (McLean et al., 2014). We showed that the Gram‐positive lactic acid bacteria, which are often present in probiotic supplements or food products, are not susceptible at peptide concentrations that are bactericidal to these oral pathogens (McLean et al., 2014). This highlights the potential of these peptides for selective antimicrobial therapy against such oral pathogenic bacteria. Both the multidrug‐resistant and antibiotic‐sensitive strains of S. pseudintermedius and E. faecium were sensitive to similar concentrations of AMPs, suggesting no cross‐resistance.

We also tested the potential cytotoxicity of selected peptides against human PBMCs, as it would be important not to inhibit the defensive immune response of the host if these peptides were used as topical applications to treat infections. We found that concentrations of peptides that effectively inhibited bacteria did not cause necrosis or apoptosis against human PBMCs.

Based on this study, we propose that peptides alyteserin‐1c, PGLa‐AM1, PGLa‐LM1, CPF‐AM1, temporin‐1DRa and its [Lys4], [Lys5], [Aib8], and [Aib9] analogues are interesting candidates for further research into potential use as novel topical therapeutics for treatment of skin infections caused by antibiotic‐resistant bacteria. Based on the observed MIC values, temporin‐1DRa shows great promise to be used to treat canine skin infections by S. pseudintermedius, a bacterium that causes high morbidity and seriously lower the quality of life of affected dogs (Bannoehr & Guardabassi, 2012). Moreover, the hymenochirin‐2B and ‐4B peptides displayed high potency against multidrug‐resistant, A. baumannii, pathogens that cause severe wound infections (Guerrero et al., 2010) and are an important cause of difficult to treat nosocomial infections (Michalopoulos & Falagas, 2010). The differential activity of these antimicrobials against several pathogenic bacteria but not lactic acid bacteria might be advantageous as many commensal species of bacteria including lactobacilli are considered beneficial and potentially contribute toward colonization resistance against pathogenic bacteria (Belkaid & Tamoutounour, 2016; Grice et al., 2009). For example, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG has been shown to effectively interfere with intestinal colonization by Enterococcus faecium. Thus, HDPs reported here that have up to ninefold higher MIC values for commensal lactobacilli than E. faecium might be advantageous in treatment of intensive care patients with intestinal colonization by vancomycin‐resistant enterococcus (Jung, Byun, Lee, Moon, & Lee, 2014; Tytgat et al., 2016).

Recently, several biotechnological tools have become available that open up avenues to develop promising applications for AMPs, including the peptides described in this study (de Vries, Andrade, Bakuzis, Mandal, & Franco, 2015). Tethering and display of AMPs on nanoparticles, fibers or polymers for localized and controlled delivery, increased stability and enhanced activity are examples of possible therapeutic applications of AMPs against MDR pathogenic bacteria in the future.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None declared.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Arshnee Moodley from the University of Copenhagen and Dr. John Hays from Erasmus University Medical Centre Rotterdam (EMC) for making their bacterial isolates available. This study has been funded by the Marie Curie Actions under the Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development of the EU (Grant Agreement 289285).

Gaiser RA, Ayerra Mangado J, Mechkarska M, et al. Selection of antimicrobial frog peptides and temporin‐1DRa analogues for treatment of bacterial infections based on their cytotoxicity and differential activity against pathogens. Chem Biol Drug Des.2020;96:1103–1113. 10.1111/cbdd.13569

5. DATA AVAILABILITY

Raw data will be made available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Afacan, N. J. , Yeung, A. T. , Pena, O. M. , & Hancock, R. E. (2012). Therapeutic potential of host defense peptides in antibiotic‐resistant infections. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 18, 807–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Ghaferi, N. , Kolodziejek, J. , Nowotny, N. , Coquet, L. , Jouenne, T. , Leprince, J. , … Conlon, J. M. (2010). Antimicrobial peptides from the skin secretions of the South‐East Asian frog Hylarana erythraea (Ranidae). Peptides, 31, 548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M. F. , Soto, A. , Knoop, F. C. , & Conlon, J. M. (2001). Antimicrobial peptides isolated from skin secretions of the diploid frog, Xenopus tropicalis (Pipidae). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1550, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannoehr, J. , & Guardabassi, L. (2012). Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in the dog: Taxonomy, diagnostics, ecology, epidemiology and pathogenicity. Veterinary Dermatology, 23, 253–266, e51‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid, Y. , & Tamoutounour, S. (2016). The influence of skin microorganisms on cutaneous immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology, 16, 353–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas, IA , & Mollstam, B . (1998) Treatment of diarrhea, Patent No. US 5837238 A.

- Conlon, J. M. (2011a). Structural diversity and species distribution of host‐defense peptides in frog skin secretions. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 68, 2303–2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon, J. M. (2011b). The contribution of skin antimicrobial peptides to the system of innate immunity in anurans. Cell and Tissue Research, 343, 201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon, J. M. , Al‐Ghafari, N. , Coquet, L. , Leprince, J. , Jouenne, T. , Vaudry, H. , & Davidson, C. (2006). Evidence from peptidomic analysis of skin secretions that the red‐legged frogs, Rana aurora draytonii and Rana aurora aurora, are distinct species. Peptides, 27, 1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon, J. M. , Al‐Ghaferi, N. , Abraham, B. , & Leprince, J. (2007). Strategies for transformation of naturally‐occurring amphibian antimicrobial peptides into therapeutically valuable anti‐infective agents. Methods, 42, 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon, J. M. , Al‐Ghaferi, N. , Ahmed, E. , Meetani, M. A. , Leprince, J. , & Nielsen, P. F. (2010). Orthologs of magainin, PGLa, procaerulein‐derived, and proxenopsin‐derived peptides from skin secretions of the octoploid frog Xenopus amieti (Pipidae). Peptides, 31, 989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon, J. M. , Al‐Kharrge, R. , Ahmed, E. , Raza, H. , Galadari, S. , & Condamine, E. (2007). Effect of aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) substitutions on the antimicrobial and cytolytic activities of the frog skin peptide, temporin‐1DRa. Peptides, 28, 2075–2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon, J. M. , Demandt, A. , Nielsen, P. F. , Leprince, J. , Vaudry, H. , & Woodhams, D. C. (2009). The alyteserins: Two families of antimicrobial peptides from the skin secretions of the midwife toad Alytes obstetricans (Alytidae). Peptides, 30, 1069–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon, J. M. , & Mechkarska, M. (2014). Host‐defense peptides with therapeutic potential from skin secretions of frogs from the family pipidae. Pharmaceuticals, 7, 58–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, R. , Andrade, C. A. S. , Bakuzis, A. F. , Mandal, S. M. , & Franco, O. L. (2015). Next‐generation nanoantibacterial tools developed from peptides. Nanomedicine, 10, 1643–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel, L. S. , Hill, J. M. , Caballero, A. R. , Green, L. C. , & O'Callaghan, R. J. (1998). Protease IV, a unique extracellular protease and virulence factor from Pseudomonas aeruginosa . The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273, 16792–16797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST . (2014). MIC distributions and ECOFFs.

- Funke, G. , Monnet, D. , deBernardis, C. , von Graevenitz, A. , & Freney, J. (1998). Evaluation of the VITEK 2 system for rapid identification of medically relevant gram‐negative rods. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 36, 1948–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia‐Garrote, F. , Cercenado, E. , & Bouza, E. (2000). Evaluation of a new system, VITEK 2, for identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of enterococci. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 38, 2108–2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini, M. G. , Poulter, L. , Gibson, B. W. , & Williams, D. H. (1987). Biosynthesis and degradation of peptides derived from Xenopus laevis prohormones. Biochemical Journal, 243, 113–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice, E. A. , Kong, H. H. , Conlan, S. , Deming, C. B. , Davis, J. , Young, A. C. , … Segre, J. A. (2009). Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science, 324, 1190–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, D. M. , Perez, F. , Conger, N. G. , Solomkin, J. S. , Adams, M. D. , Rather, P. N. , & Bonomo, R. A. (2010). Acinetobacter baumannii‐associated skin and soft tissue infections: Recognizing a broadening spectrum of disease. Surgical Infections, 11, 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, A. C. D. G. (1956). The isolation and classification of Lactobacillus strains from Italian saliva samples. British Dental Journal, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Institute CLaS (2008). Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Wayne, PA: CLSI. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, E. , Byun, S. , Lee, H. , Moon, S. Y. , & Lee, H. (2014). Vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus colonization in the intensive care unit: Clinical outcomes and attributable costs of hospitalization. American Journal of Infection Control, 42, 1062–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karle, I. L. , & Balaram, P. (1990). Structural characteristics of alpha‐helical peptide molecules containing Aib residues. Biochemistry, 29, 6747–6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig, E. , Bininda‐Emonds, O. R. , & Shaw, C. (2015). The diversity and evolution of anuran skin peptides. Peptides, 63, 96–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte, J. , & Doolittle, R. F. (1982). A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. Journal of Molecular Biology, 157, 105–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni, M. L. , McDermott, A. M. , & Zasloff, M. (2016). Antimicrobial peptides and wound healing: Biological and therapeutic considerations. Experimental Dermatology, 25, 167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean, D. T. , McCrudden, M. T. , Linden, G. J. , Irwin, C. R. , Conlon, J. M. , & Lundy, F. T. (2014). Antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties of PGLa‐AM1, CPF‐AM1, and magainin‐AM1: Potent activity against oral pathogens. Regulatory Peptides, 194–195, 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechkarska, M. , Meetani, M. , Michalak, P. , Vaksman, Z. , Takada, K. , & Conlon, J. M. (2012). Hybridization between the African clawed frogs Xenopus laevis and Xenopus muelleri (Pipidae) increases the multiplicity of antimicrobial peptides in skin secretions of female offspring. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D, Genomics & Proteomics, 7, 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechkarska, M. , Prajeep, M. , Coquet, L. , Leprince, J. , Jouenne, T. , Vaudry, H. , … Conlon, J. M. (2012). The hymenochirins: A family of host‐defense peptides from the Congo dwarf clawed frog Hymenochirus boettgeri (Pipidae). Peptides, 35, 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink, M. , Wells, J. M. , Taverne, N. , de Zeeuw Brouwer, M.‐L. , Hilhorst, B. , Venema, K. , & van Bilsen, J. (2012). Immunomodulatory effects of potential probiotics in a mouse peanut sensitization model. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, 65, 488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalopoulos, A. , & Falagas, M. E. (2010). Treatment of Acinetobacter infections. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 11, 779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, V. , & Serrano, L. (1994). Elucidating the folding problem of helical peptides using empirical parameters. Natural Structural Biology, 1, 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson III, L. , Soto, A. M. , Knoop, F. C. , & Conlon, J. M. (2001). Pseudin‐2: An antimicrobial peptide with low hemolytic activity from the skin of the paradoxical frog. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 288, 1001–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong, P. Y. , Ohtake, T. , Brandt, C. , Strickland, I. , Boguniewicz, M. , Ganz, T. , … Leung, D. Y. (2002). Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347, 1151–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, A. I. , Sharov, V. , White, J. , Li, J. , Liang, W. , Bhagabati, N. , … Quackenbush, J. (2003). TM4: A free, open‐source system for microarray data management and analysis. BioTechniques, 34, 374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat, H. L. P. , Douillard, F. P. , Reunanen, J. , Rasinkangas, P. , Hendrickx, A. P. A. , Laine, P. K. , … de Vos, W. M. (2016). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG outcompetes Enterococcus faecium by mucus‐binding pili – Evidence for a novel probiotic mechanism on a distance. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 82(19), 5756–5762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hemert, S. , Meijerink, M. , Molenaar, D. , Bron, P. A. , de Vos, P. , Kleerebezem, M. , … Marco, M. L. (2010). Identification of Lactobacillus plantarum genes modulating the cytokine response of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. BMC Microbiology, 10, 293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecht, U. , Wisselink, H. J. , van Dijk, J. E. , & Smith, H. E. (1992). Virulence of Streptococcus suis type 2 strains in newborn germfree pigs depends on phenotype. Infection and Immunity, 60, 550–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. , Li, X. , & Wang, Z. (2015). APD3: The antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education. Nucleic Acids Research, 44, D1087–D1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, A. T. Y. , Gellatly, S. L. , & Hancock, R. E. W. (2011). Multifunctional cationic host defence peptides and their clinical applications. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 68, 2161–2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff, M. (1987). Magainins, a class of antimicrobial peptides from Xenopus skin: Isolation, characterization of two active forms, and partial cDNA sequence of a precursor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 84, 5449–5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data will be made available upon reasonable request.