Abstract

Currently, the world is under a pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This disease is characterized by a respiratory syndrome that can progress to an acute respiratory distress syndrome. To date, limited effective therapies are available for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19; therefore, it is necessary to propose novel treatment options with immunomodulatory effects. Vitamin D serves functions in bone health and has been recently reported to exert protective effects against respiratory infections. Observational studies have demonstrated an association between vitamin D deficiency and a poor prognosis of COVID-19; this is alarming as vitamin D deficiency is a global health problem. In Latin America, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is unknown, and currently, this region is in the top 10 according to the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases. Supplementation with vitamin D may be a useful adjunctive treatment for the prevention of COVID-19 complications. The present review provides an overview of the current knowledge of the potential immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D in the prevention of COVID-19 and sets out vitamin D recommendations for the Latin American population.

Keywords: vitamin D, ergocalciferol, cholecalciferol, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, coronavirus, coronavirus disease 2019, prevention, immunomodulation, respiratory tract infections, Latin America

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) belong to one of the four genera of the Coronaviridae family characterized by a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome of ~30 kb (1). Previously, CoVs were considered serious pathogens in animals with low influence on human health (1-3). However, at the beginning of the 21st century, the outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV emerged, followed by the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV a decade later, confirming the animal-to-human and human-to-human transmission of CoVs (1,4,5). Currently, the world is under a pandemic of the third wave of CoV, initially identified as 2019-novel CoV that emerged in December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China (6); following phylogeny analysis and taxonomy, and based on the established naming practice for viruses in this genus, the Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy Viruses termed the novel virus SARS-CoV-2 (7). Subsequently, on February 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 would be named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (8). This disease is characterized by a respiratory syndrome that can progress to severe interstitial pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (9-11). The causative agent of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, is transmitted mainly between individuals through contact, respiratory droplets and aerosols, allowing the virus to spread rapidly (8,12). The transmission rate of SARS-CoV-2 has been reported to be higher compared with that of SARS-CoV (rq=5.7 vs. ~3.0) (13,14). The mechanism of infection of SARS-CoV-2 involves the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the host lung epithelial cells to enter the cell and initiate infection (15,16). ACE2 expression levels are high in the intestine, heart, and kidneys; therefore, this virus compromises various organs (17).

The outbreak and rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 are a health threat with unprecedented consequences worldwide. On August 3, 2020, the Johns Hopkins University dashboard reported 18,282,208 confirmed cases and 693,694 deaths worldwide due to COVID-19 (18). On the same date, five Latin American countries (Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Chile and Colombia) were among the top 10 countries with the highest number of confirmed cases, and three countries in this region (Brazil, Mexico and Peru) were in the top 10 countries with the highest number of deaths (18). To date, various factors have been identified as predisposing for an aggressive phenotype of COVID-19, including the male sex, age >65 years, smoking and comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease (19). The majority of these comorbidities are associated with a sedentary lifestyle and an unhealthy diet that is commonly characterized by a high intake of saturated fats, salt, sugars, refined grains and processed meats (20,21).

A healthy diet is characterized by appropriate consumption of macronutrients and micronutrients, and is necessary for growth, development and adequate physiological functioning (21). Nutrition is also essential for the function of the immune system; this relationship is currently being studied. Particularly, it has been reported that the Mediterranean diet, as well as nutrients and active food components can modulate the immune response through the inhibition of pro-inflammatory mediators, production of anti-inflammatory functions and participation in the communication between the innate and adaptive immune system (22). For example, the Mediterranean diet (23), vitamin D (24), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) (25) have demonstrated promising effects on chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases, whereas vitamin E (26), zinc (27) and probiotics (28) exhibit effects in reducing infections. Immunonutrition is defined as the provision of nutrients in amounts greater than those typically recommended in a diet that modulates the immune system activity; immunonutrients include amino acids, PUFAs, short-chain fatty acids, vitamins and trace elements (29,30). In particular, vitamin D is a crucial immunonutrient that can be obtained through the diet; however, it is produced mostly (80%) endogenously by induction of ultraviolet-B (UV-B) rays in the skin (31). Although the primary function of vitamin D appears to be calcium homeostasis, this vitamin also serves immunomodulatory functions and may have protective effects against respiratory infections (32).

Vitamin D deficiency is considered a public health problem worldwide; it is estimated that one billion individuals are deficient in vitamin D, and that insufficiency affects ~50% of the population (33). Various factors influence vitamin D deficiency, such as age, geographic latitude and skin pigmentation (34). In Latin American countries, vitamin D insufficiency has been suggested to be a potential public health problem; however, no representative data are available from this region, and the magnitude of the problem cannot be established (35).

Based on the aforementioned information, the restoration of adequate serum levels of vitamin D through supplementation has demonstrated a protective effect against respiratory infections (32). In addition, considering the lack of effective therapies for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19, it is essential to propose novel therapeutic options. Therefore, the present review aims to overview the potential immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D in the prevention of COVID-19 and to establish guideline recommendations for vitamin D supplementation for the Latin American population.

2. SARS-CoV-2 infection

Until late December 2019, only six CoV species had been identified with implications for human health, of which four (229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1) can cause mild symptoms such as the common cold (6). Currently, SARS-CoV-2, in addition to the other two remaining CoV strains (SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV), can cause fatal outcomes (6). The genome of SARS-CoV-2 shares 79% similarity with that of SARS-CoV (36). The CoV genome encodes four main proteins: Spike, membrane, nucleocapsid and envelope (1,9). The spike protein of the virus is responsible for the viral entry to the host cells by recognizing and binding to the ACE2 receptor, which is highly expressed in various types of cells, including type II alveolar and myocardial cells, as well as the proximal tubule cells of the kidney (17,37,38). The virus spike protein binding with the ACE2 receptor is proteolytically processed by the transmembrane serine protease 2, which causes the cleavage of ACE2 and the activation of the virus spike protein to facilitate its entry to the target cell (16,39). Once inside the cell, the viral RNA genome is released into the cytoplasm to begin its replication process (40).

ARDS is one of the features of the severe COVID-19 as the virus can negatively regulate the expression of ACE2, causing the upregulation of angiotensin II (Ang II), which interacts with the Ang II type 1 receptor (AT1R) to modulate the nuclear factor-KB (NF-KB) signaling pathway, as well as macrophage activation that leads to the excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (41). This exacerbated cytokine production is commonly referred to as a cytokine storm, which, in addition to contributing to ARDS, triggers a pathogenic inflammatory immune response that leads to multiple organ failure and death in severe COVID-19 (41-43).

3. Latin America: A vulnerable region

On March 11, 2020, the WHO classified COVID-19 as a pandemic due to the alarming worldwide spread of the virus and governments' inaction to prevent infection (8). A number of Latin American countries are currently among the countries with the highest number of confirmed cases and deaths associated with COVID-19 (18). Vulnerability to COVID-19 in Latin America is caused by various factors such as precarious health systems, housing conditions, high rates of non-communicable diseases, income inequality, and poverty levels (44,45). Although some countries in this region have already started vaccinating their population (Costa Rica, Argentina, Mexico, and Chile) (46), accessibility and individual factors (socioeconomic, education, religious and cultural) may affect vaccine coverage (47).

Clinical trials have been conducted to identify a treatment for COVID-19; however, limited effective therapies are available for the prevention or treatment of this disease (48-52). Furthermore, despite the current availability of vaccines, their distribution may not be equitable since during the 2009 H1N1 swine flu pandemic, countries with the highest economic position left the poorer countries with limited supplies (53,54). In addition, although health services in Latin America have notably improved since 1950, there are still deficiencies and inequity in health care (55). Therefore, it is important to propose host-directed therapeutic alternatives of easy access such as immunonutrients that may modulate the immune response to minimize the mortality rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection until a universal and effective solution is identified (56). One of the immunonutrients that has received the most interest is vitamin D; the sufficiency in serum levels of this vitamin in individuals may lead to a less severe course of COVID-19 and a faster recovery compared with that in individuals with vitamin D deficiency by helping prevent the cytokine storm, as well as ARDS, which is one of the leading causes of mortality among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (57).

4. Vitamin D

V itamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin present in two main isoforms; vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) which is mainly present in mushrooms, and vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), which is abundant in fish, egg yolk and liver (58). Chylomicrons support intestinal absorption of both vitamin D isoforms; however, vitamin D3 is more easily absorbed compared with vitamin D2 (33,58). However, achieving the recommended vitamin D dose from food sources may be impossible for a large part of the population (31,58).

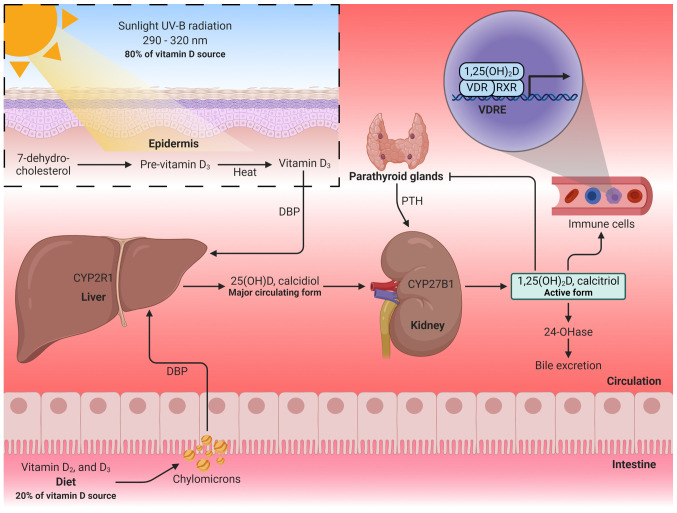

As aforementioned, the major source of vitamin D for physiological functions is through synthesis in the epidermis from a cholesterol precursor (7-dehydrocholesterol) following exposure to UV-B radiation (290-320 nm) from the sun (31,59). This process induces to the formation of pre-vitamin D3, which isomerizes to vitamin D3 in a thermo-sensitive process (60). Dietary or skin-synthesized vitamin D3 binds to the vitamin D-binding protein (DBP), which transports it to the liver, where it is metabolized mainly by the enzyme vitamin D-25-hydroxylase to form calcidiol, also termed 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] (59). Subsequently, 25(OH)D is transformed in the kidneys by cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily B member 1 (CYP27B1, also termed 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase) to obtain 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], also termed calcitriol, which is the main active form of vitamin D responsible for its physiological functions (59,60). In the regulation of calcitriol production, parathyroid hormone (PTH) has the ability to stimulate renal calcitriol production by activating CYP27B1, whereas fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) and calcitriol itself inhibit CYP27B1 (60,61). Similarly, high serum calcium and calcitriol concentrations inhibit CYP27B1 indirectly by suppressing PTH, and high serum phosphate concentration suppresses renal calcitriol production through the stimulation of FGF-23 (61). Excess 1,25(OH)2D is excreted through the bile or urine as calcitroic acid (Fig. 1) (31,62).

Figure 1.

Vitamin D metabolism. Vitamin D is obtained through diet or skin synthesis by sun exposure and is converted to calcidiol in the liver. Subsequently, a second hydroxylation in the kidneys transforms calcidiol into calcitriol (active form of vitamin D). Calcitriol binds to the VDR and forms a complex with the RXR to regulate gene transcription. 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; VDR, vitamin D receptor; RXR, retinoid-X receptor; VDREs, vitamin D response elements; PTH, parathyroid hormone; 24-OHase, 25-hydroxyvitamin D-24-hydroxylase. The figure was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com/).

Calcitriol exerts its genomic functions through the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which acts as a transcription factor that forms a complex with the retinoid-X receptor (RXR); this complex recruits transcriptional coactivators or corepressors to regulate gene transcription by binding to vitamin D response elements (VDREs) in the DNA (59,60). In addition to the endocrine function of calcitriol in regulating calcium levels for bone remodeling, extrarenal hydroxylation occurs to form calcitriol, exerting paracrine and autocrine effects (61,63). Extrarenal hydroxylation by CYP27B1 occurs in the prostate, brain, placenta, lungs and immune cells (63). In particular, VDR activation by locally produced calcitriol has been reported to mediate the immune response (62-64), as discussed in the following sections.

5. Vitamin D and respiratory infection

Among the most common viruses that affect human health through respiratory tract infections are influenza viruses, classified into four types. Influenza type A is the most common in seasonal epidemics and pandemics, and is the primary cause of a severe illness that is associated with high mortality rates in high-risk populations (adults >65 years, individuals with chronic diseases or immunosuppression, pregnant women, individuals with obesity and infants ≤6 months) (65). The influenza viruses exhibit typical winter infection peaks in temperate zones (66), which correspond to November to April and May to October in the northern and southern hemisphere, respectively (65). By contrast, in tropical zones, the seasonality of influenza infections appears to be poorly defined, although it is assumed that it can occur throughout the year (65,67).

In 1981, Hope-Simpson (68) was the first to describe the association between influenza infection peaks and temperate latitudes in the winter. He proposed the existence of a seasonal stimulus associated with the seasonality of epidemic influenza, and that the decrease in solar radiation during winter influenced the presence of the seasonal stimulus. The study also suggested that, in the tropical regions, although UV-B radiation is less seasonal, influenza outbreaks are more severe during the rainy seasons. Thus, Hope-Simpson described that latitude determined the time of epidemics in the annual cycle, since solar radiation may act positively or negatively on the virus, the host or their interaction (68). After >20 years, Cannell et al (69) proposed that vitamin D was a likely candidate to be the seasonal stimulus described by Hope-Simpson. Since vitamin D3 is obtained by sun exposure, the serum levels of 25(OH)D are lower in people who live in temperate latitudes, and because vitamin D has modulating effects on the immune system (69).

Based on the aforementioned theories, it has been reported that the levels of UV-B radiation in countries outside the 40° N and 40° S latitude range are insufficient to produce vitamin D in the skin during winter (70). The average concentration of 25(OH)D in European countries during winter has been reported to be 11.6 ng/ml (29 nmol/l) (71), 14.3 ng/ml (35.75 nmol/l) (72) and 13.3 ng/ml (33.25 nmol/l) (73). Similarly, in the northern and central regions of the United States of America, the concentration of 25(OH)D during winter is ~21 ng/ml (52.5 nmol/l), whereas in the summer, it is ~28 ng/ml (70 nmol/l) (74). Canada has reported that between December and January (winter), there is a peak in the prevalence of 25(OH)D insufficiency/deficiency in its population (75). Although the influence of solar radiation on vitamin D deficiency is evident, several additional factors impact its deficiency, which will be discussed in subsequent sections. These factors can also affect the tropical zone population, such as that in Latin America, although the intensity of the sun rays in this region is greater (70). Other factors associated with the seasonality of respiratory infections include the congregation indoors during winter, which increases the probability of contagion, as well as the cold and dry conditions that contribute to the influenza transmission (69,76,77). A recent meta-analysis of 14 observational studies has reported that a low serum concentration of 25(OH)D is a risk factor for acute respiratory tract infection (OR=1.83; 95% CI, 1.42-2.37; P-value for heterogeneity, <0.001) (78). Similarly, in a sub-analysis of four studies, a low serum concentration of 25(OH)D was associated with high mortality from acute respiratory tract infection (OR=3.00; 95% CI, 1.89-4.78; P-value for heterogeneity, 0.029). Notably, the funnel plot in the aforementioned study identified evidence of publication bias (78). By contrast, a meta-analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials has reported that vitamin D supplementation is associated with a lower risk of acute respiratory tract infections (OR=0.88; 95% CI, 0.81-0.96; P=0.003; P-value for heterogeneity, <0.001) (32).

6. Vitamin D and COVID-19

CoVs cause respiratory infections ranging from the common cold to severe conditions such as pneumonia and ARDS (1,6,10). Therefore, the immunoregulatory effects of vitamin D are being discussed due to its potential beneficial effects for clinical outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 infection. In the international platforms for the registration of clinical trials, a number of studies evaluating the effects of vitamin D supplementation on COVID-19 have been registered, although the majority of these studies have not yet reported any results. Despite this temporal limitation, numerous studies support the association between vitamin D and the clinical outcomes of COVID-19.

Among the observational studies published in the first semester of 2020, significant associations were reported between latitudes and mortality from COVID-19, as well as between 25(OH)D deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection (57,79-84). These studies are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Observational studies of the association between vitamin D and COVID-19.

| First author, year | Study design | Subjects or countries | Main outcome | Conclusion | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodes et al, 2020 | Ecological | 120 countries | Correlation of latitude degrees with mortality from COVID-19 per million in different countries: rho=0.53; P≤0.0001 | Mortality per million is higher in countries with a latitude above 35° n; above this latitude, people do not receive sufficient sunlight to retain adequate vitamin D levels during winter | (57) |

| Ilie et al, 2020 | Ecological | 20 countries | Correlation of mortality from COVID-19 per million with a mean 25(OH)D concentration in different countries: r=-0.43; P=0.05 | The association may explain the possible protection of vitamin D from the negative consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection | (79) |

| Hastie et al, 2020 | Ecological | 1,474 subjects | Association of 25(OH)D concentration with positive COVID-19: OR=1.00; 95% CI, 0.998-1.01; P=0.208 | The results do not support the potential of 25(OH)D concentration for susceptibility to COVID-19 infection | (80) |

| D'Avolio et al, 2020 | Retrospective | 107 subjects | Difference of 25(OH)D concentration in the positive and negative SARS-CoV-2 groups: 11.1 ng/mla (IQR, 8.2-21.0) vs. 24.6 ng/mla (IQR, 8.9-30.5); P=0.004 | Low concentration of 25(OH)D may represent a risk factor for infection with SARS-CoV-2 | (81) |

| Meltzer et al, 2020 | Retrospective | 499 subjects | Association of 25(OH)D deficiency with a positive test for COVID-19: RR=1.77; P=0.015 | Individuals with vitamin D deficiency have a higher risk of a positive test for COVID-19 compared with those with sufficiency | (82) |

| Whittemore, 2020 | Ecological | 88 countries | Correlation of latitude with death rates per million from COVID-19 in different countries: r=0.40; P≤0.00005 | Mortality per million is lower in populations closest to the Equator. The correlation supports a possible association between latitude, sunlight exposure, vitamin D and COVID-19 mortality | (83) |

| Panagiotou et al, 2020 | retrospective | 134 subjects | Difference in the prevalence of 25(OH)D sufficiency between ICU and non-ICU patients: 19 vs. 39.1%; P=0.02 | 25(OH)D deficiency was more prevalent in patients who required admission to the ICu than those who only needed management in medical wards; therefore, vitamin D could be a determinant of the severity of the disease. There was no significant association between 25(OH)D concentration and mortality | (84) |

Median. rho, Spearman's correlation coefficient; r, Pearson's correlation coefficient; IQR, interquartile range; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; ICU, intensive care unit. 1 ng/ml=2.5 nmol/l.

Studies from the second half of 2020 that include observational, quasi-experimental studies and clinical trials have also reported valuable information on the association between vitamin D and COVID-19. A number of these studies are described below.

Merzon et al (85) evaluated the association between low levels of 25(OH)D and the risk of infection by COVID-19 through an ecological study (secondary data analysis from population databases). The mean serum of 25(OH)D concentration was lower in the positive compared with the negative COVID-19 cases (P=0.026). In addition, an association was demonstrated between 25(OH)D <30 ng/ml (<75 nmol/l) and the risk of infection by SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, it was concluded that suboptimal plasma levels of 25(OH)D may be a potential risk factor for COVID-19. Another study identified that the GT rs7041 genotype of the DBP gene may confer susceptibility to COVID-19, whereas the TT rs7041 genotype may exert a protective effect (86). The authors of the aforementioned study considered that polymorphisms in the DBP gene may alter the affinity of DBP for vitamin D metabolites, which may affect COVID-19 prevalence and mortality.

In a retrospective study, Carpagnano et al (87) reported that patients with 25(OH)D concentration <10 ng/ml (25 nmol/l) had a 50% probability of mortality, whereas the risk for those with a concentration >10 ng/ml was only 5% (P=0.019). Therefore, the authors concluded that vitamin D deficiency may be a risk factor for mortality in patients with COVID-19 (87). Similar results were obtained in other studies, which reported that vitamin D deficiency significantly increased the risk of mortality from COVID-19 (88,89). By contrast, Ling et al (90) reported no significant association between serum concentrations of 25(OH)D and COVID-19 mortality. However, multivariate analysis revealed that treatment with high-dose vitamin D3 booster therapy reduced the risk of mortality (90). Therefore, Ling et al (90) consider that vitamin D3, due to its low cost, may be a potential therapeutic option for COVID-19 worldwide.

A cross-sectional study reported vitamin D deficiency (<12 ng/ml; <30 nmol/l) in 15.6% of the samples from individuals with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, and the presence of antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 virus was higher in subjects with vitamin D deficiency compared with that in individuals with higher levels of 25(OH)D (P=0.003) (91). In addition, vitamin D deficiency was identified as an independent factor for seropositivity to SARS-CoV-2 in subjects with COVID-19 symptoms (91). Therefore, Faniyi et al (91) conclude that supplementation with vitamin D may be an adequate therapeutic strategy for preventing or alleviating COVID-19.

In a case-control study by Ye et al (92), it was reported that patients with COVID-19 presented with lower levels of 25(OH)D compared with those in healthy control subjects (P<0.05). A subsequent sub-group analysis comparing mild and severe COVID-19 cases identified a significant association between vitamin D deficiency and COVID-19 severity (92).

A prospective cohort study comparing asymptomatic individuals (group A) vs. patients with severe COVID-19 (group B) reported a lower concentration of 25(OH)D in group B (P=0.0001). The incidence of vitamin D deficiency (<20 ng/ml; <50 nmol/l) and mortality were higher in group B compared with those in group A (93). In a sub-analysis, patients with 25(OH)D concentration <20 ng/ml (50 nmol/l) presented with significantly higher serum concentrations of IL-6 (P=0.0300) and ferritin (P=0.0003) compared with those in patients with a concentration ≥20 ng/ml; thus, the authors concluded that vitamin D deficiency may increase the inflammatory status and the possibility of a severe COVID-19 phenotype (93). By contrast, another prospective cohort study (94) reported no associations between vitamin D deficiency and clinical features of patients with COVID-19; however, the authors suggested that this result may be due to the evaluated population mainly comprising comorbid elderly patients.

In a quasi-experimental study by Annweiler et al (95), 66 elderly patients (mean age, 87.7+9.0 years) with COVID-19 residing in a nursing home were evaluated. The intervention group included patients who received an oral bolus of 80,000 IU (2,000 ^g) vitamin D3 as part of the routine maintenance treatment; the control group did not receive vitamin D3 supplementation. The results demonstrated that vitamin D3 had a protective effect on mortality, as the survival analysis revealed a shorter survival time among residents who did not receive vitamin D supplementation (P=0.002). Similar results were reported in another quasi-experimental study by Annweiler et al (96). Additionally, it was suggested that long-term regular vitamin D supplementation may protect against infections such as SARS-CoV-2 more effectively compared with oral bolus administered after COVID-19 diagnosis (96).

An open-label clinical trial evaluated whether calcifediol treatment may reduce the need for admission of patients with COVID-19 to the intensive care unit (ICU) (97). The intervention group received calcifediol and standard treatment (azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine); the control group only received the standard treatment. The patients were followed-up until they were admitted to the ICU, discharged or succumbed to the disease. The probability of admission to the ICU was significantly lower in the intervention group (2%) compared with that in the control group (50%) (P<0.001) (97). Therefore, Entrenas Castillo et al (97) concluded that calcifediol may improve the clinical outcome of subjects with COVID-19.

Rastogi et al (98) conducted a clinical trial to evaluate the effects of high-dose vitamin D3 on SARS-CoV-2 viral clearance. Patients with mild symptoms or asymptomatic individuals positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection and with vitamin D deficiency were randomly assigned to the intervention group to receive 60,000 IU (1,500 ^g) of vitamin D3 daily, or the control group, who received a placebo. The intervention was performed daily for 7 days. Patients who reached a concentration >50 ng/ml of 25(OH)D received only one additional dose of 60,000 IU, whereas those who did not reach the desired 25(OH)D levels received the same daily dose until day 14. The patients were evaluated periodically until day 21 or virus negativity. In the intervention group, ~63% of the subjects had a negative result for SARS-CoV-2, whereas only 20.8% of those in the control group had this outcome (P=0.018). In addition, the intervention group presented with a more pronounced decrease in fibrinogen levels compared with that in the control group (P=0.001). No episodes of hypercalcemia were observed in the evaluated population (98). Therefore, Rastogi et al (98) considered that vitamin D may reduce the transmission rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A recent meta-analysis has reported that insufficient vitamin D levels increase the rates of hospitalization and mortality among patients with COVID-19 (99). Severe cases have a higher probability of vitamin D deficiency (OR=1.64; 95% CI, 1.30-2.09; I2=35.7%). Thus, vitamin D intervention as an adjunctive treatment may be crucial in severe cases of COVID-19 with low 25(OH)D levels. Similarly, supplementation in therapeutic doses may be useful for the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to D'Avolio et al (81), Meltzer et al (82), Merzon et al (85) and Faniyi et al (91), since the active metabolite of vitamin D exerts biological activities in the innate immune system, in particular, through the maintenance of the integrity of physical barriers and the promotion of antimicrobial peptides (64). In addition, another meta-analysis has reported an association between low 25(OH)D levels and the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR=1.43; 95% CI, 1.00-2.05) (100). However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the heterogeneity of the included studies (I2=64.9%; P=0.036) and the risk of publication bias. Finally, according to the meta-analysis by Martineau et al (32), vitamin D supplementation did not significantly affect any types of adverse events. However, the individual recommendatios of vitamin D3 for preventive or adjuvant treatment should be evaluated by a physician. Similarly, a consensus is considered necessary to propose public health policies for supplementation with this vitamin in risk groups.

7. Immunomodulatory mechanisms of vitamin D

As aforementioned, vitamin D in its active form [1,25(OH)2D or calcitriol] binds to the VDR and RXR to regulate gene transcription. The classic functions of vitamin D are the regulation of calcium absorption, homeostasis, bone metabolism, cell growth and division (61). In addition, VDR is expressed in immune cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells (Dcs), B and T lymphocytes, and neutrophils, suggesting that vitamin D may be an important regulator of the immune system (101,102).

Physical barriers

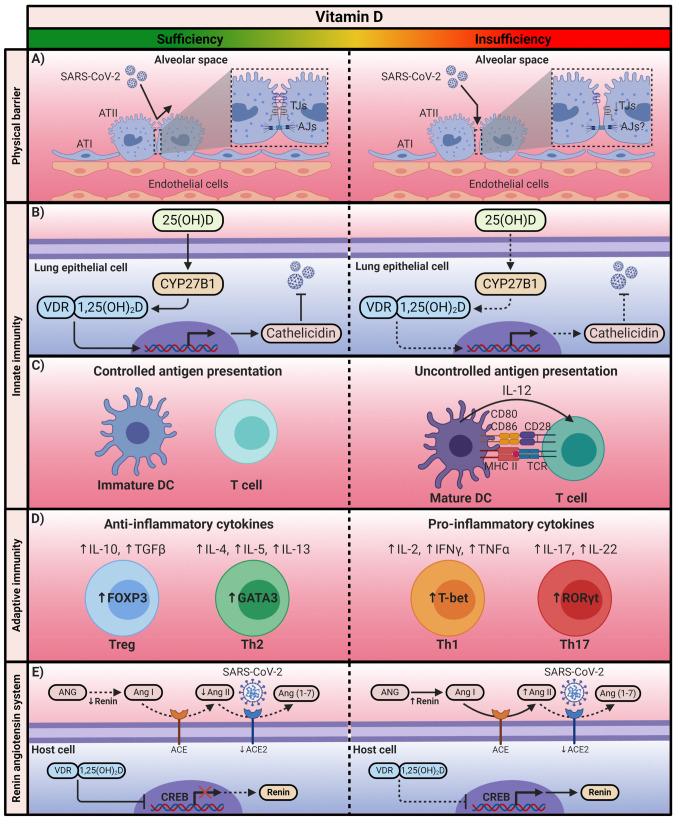

Physical barriers are the first line of defense against infection. Currently, the prevention and treatment of diseases focus on the preservation and restoration of the proper functioning of epithelial cells (103). In the pulmonary epithelium, the severity of acute lung injury is associated with its barrier dysfunction (104). To maintain the integrity of the alveolar wall, which forms a physical barrier against the external environment, the integrity of tight junctions (TJs) and adherens junctions (AJs) between the alveolar epithelial cells is essential (105). Epithelial TJs create a barrier that regulates the paracellular permeability of small molecules (106). The composition of TJs includes occludin, claudins and zonula occludens (ZO) proteins (105). AJs mainly comprise transmembrane proteins such as E-cadherin, as well as intracellular components (β-catenin and a-catenin), which regulate the adhesion of cells to their neighbors (105,106). A recent study has reported that in VDR−/− mice, the mRNA levels of claudins 2, 4, 10, 12, 15, and 18, as well as the protein levels of claudins 2, 4, 12, and 18 were significantly decreased compared with those in wild-type (WT) mice (107). In addition, another study reported a significant decrease in mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1 and occludin in VDR−/− compared with WT mice (108). In both studies, VDR−/− mice exhibited significant increases in the levels of inflammatory mediators compared with those in WT mice; therefore, these results suggest that VDR may serve a crucial role in maintaining lung permeability (Fig. 2A) (107,108).

Figure 2.

The immunomodulatory mechanism of Vitamin D. Calcitriol exerts its immunomodulatory effects through the positive or negative regulation of the transcription of the genes associated with the immune system and the renin-angiotensin system. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; VDR, vitamin D receptor; ATI, alveolar type I cell; ATII, alveolar type II cell; TJs, tight junctions; AJs, adherens junctions; CYP27B1, cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily B member 1; DCs, dendritic cells; MCH II, major histocompatibility complex class II; TCR, T-cell receptor; FOXP3, forkhead box P3; GATA3, GATA-binding protein 3; T-bet, T-box transcription factor TBX21; RORγt, Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γt; ANG, angiotensinogen; Ang, angiotensin; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein. The figure was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com/).

Innate immunity

The innate immune response is responsible for the early recognition of invading pathogens to prevent infection (109). This action is mainly carried out by pathogen-recognition receptors, among which the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are prominent (110). In monocytes, the heterodimer TLR2/1 interaction with pathogens induces antimicrobial peptides such as β-defensins and human cathelicidin (LL-37), as well as the activation of autophagy and phagolysosomal fusion (109,110). These antimicrobial peptides neutralize infection by disturbing the pathogen membrane homeostasis and promoting autophagy (109,111). Cathelicidin and autophagy complement each other to enhance pathogen clearance (110). TLR activation induces the expression of CYP27B1 and VDR in monocytes; subsequently, locally produced 1,25(OH)2D exerts its function through VDRs to upregulate the expression of p-defensins and LL-37 (112). This mechanism can also occur in epithelial cells of the intestine and the lungs, as well as in keratinocytes (111,113,114). By contrast, it has been reported that the induction of cathelicidin in lung epithelial cells is independent of TLRs (111). Previous studies have demonstrated that the antimicrobial activity of the innate immune response is partially dependent on vitamin D levels (Fig. 2B) (115-117).

Calcitriol can also alter the functioning of antigen-presenting cells, which are responsible for the initiation of the adaptive immune response. In particular, it has been described that 1,25(OH)2D can preserve an immature phenotype of DCs by reducing the expression of MHC class II molecules, as well as co-stimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86), which also results in a decline of IL-12 secretion (Fig. 2C) (118-121).

Adaptive immunity

Vitamin D also exerts immunomodulatory effects on the adaptive immune response. Calcitriol has been reported to suppress the activity of type 1 T-helper (Th1) cells, achieving the repression of pro-inflammatory cytokine production, including IL-2 and IFNγ (111). The repression of IL-2 production is mediated by the 1,25(OH)2D-VDR-RXR complex, which blocks the formation of the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) and activator protein 1 complex (122). The 1,25(OH)2D-VDR-RXR complex binds to the IL-2 promoter to interrupt the function of NFAT (111). By contrast, it has been reported that 1,25(OH)2D-VDR-RXR binds to the IFNy promoter to interfere with its activation (123). In addition, calcitriol affects the regulation of IL-17 in Th17 cells (124). Although its mechanism is not yet fully understood, it has been suggested that 1,25(OH)2D inhibits the master regulator of Th17 cells. Additionally, the 1,25(OH)2D-VDR-RXR complex competes with NFAT for the IL-17A promoter; once the complex is bound, it recruits histone deacetylases to limit the transcription of this cytokine (124-126). Calcitriol has also been demonstrated to inhibit NF-κB via upregulation of IκB expression or by interfering with the binding of NF-κB to DNA (Fig. 2D) (127-129).

By contrast, vitamin D favors the differentiation of Th2 cells and the subsequent production of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 (130,131). 1,25(OH)2D upregulates GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3), which is recognized as the master regulator of Th2 cells (130,132). This upregulation is mediated by the activation of STAT6, which acts upstream of GATA3 transcription (109,130,133). In addition, vitamin D increases the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) through the upregulation of the transcription factor FOXP3 and CTLA-4 expression; Treg differentiation contributes to the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 (Fig. 2D) (125,134-136).

Renin-angiotensin system

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) comprises renin, angiotensinogen (ANG), Ang I, Ang-converting enzyme (ACE) and Ang II (41,137). This system acts as a cascade where renin degrades ANG to produce Ang I; subsequently, the ACE transforms Ang I to II (138). Ang II regulates blood pressure and electrolyte balance (137). As aforementioned, the maintained interaction of Ang II with AT1R contributes to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by activating NF-κB and macrophages (41). The crucial role of ACE2 in this cascade is its ability to maintain a balance, since ACE2 degrades Ang II to produce Ang (1-7) with vasodilator, antiproliferative, antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory effects (139). However, in SARS-CoV-2 infection, a negative regulation of ACE2 has been demonstrated, which leads to the subsequent cytokine storm and, therefore, severe COVID-19 (41,139).

1,25(OH)2D has been reported to be an essential regulator of RAS since it suppresses the activity of renin; although the underlying mechanism is currently unclear, it has been suggested that 1,25(OH)2D suppresses renin expression by blocking the binding of the cAMP response element-binding protein with its response elements in the renin gene promoter (Fig. 2E) (140-142).

8. Causes of vitamin D deficiency

Vitamin D insufficiency affects ~50% of the world's population. The high prevalence of this vitamin insufficiency is considered a public health problem (33), since hypovitaminosis D has been identified as an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality in the general population (143). Vitamin D is commonly referred to as the 'sunshine vitamin', as most of the endogenous vitamin D is synthesized during exposure to solar UV-B rays, which causes the formation of vitamin D3 in the skin (33,70). Therefore, its deficiency is generally attributed to latitude or insufficient solar radiation; however, several additional factors contribute to low serum levels of 25(OH)D, which is a reliable marker of vitamin D status (144). These additional factors that predispose individuals to vitamin D deficiency impact tropical countries despite sufficient solar radiation intensity (70). For example, skin pigmentation and the use of sunscreens affect the synthesis of vitamin D3 in the skin (145-147), low vitamin D intake and obesity decrease the bioavailability of 25(OH)D (58,148), whereas liver failure and nephrotic syndrome alter its synthesis and excretion, respectively (149-151). Similarly, certain factors impact the catabolism and synthesis of 1,25(OH)D (152-156). These and other factors are described in detail in Table II (157-162).

Table II.

Causes of vitamin D deficiency.

| Cause | Effect | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced synthesis in the skin Sunscreen: Use of sunscreens to prevent sunburn and skin cancer Skin pigmentation: Melanin reduces the penetration of UV-B rays Time of day: The more oblique the zenith angle, the fewer UV-B photons reach the Earth's surface Aging: Decreased concentration of 7-dehydrocholesterol in the epidermis Other factors: Clothing habits, cloud cover, pollution, season and latitude |

May reduce vitamin D3 synthesis under strictly controlled conditions Reduced effectiveness of vitamin D3 synthesis in the skin The production of vitamin D3 in the skin is absent in the early hours or late in the day 50% decrease in vitamin D3 production in old age Decrease or absence of vitamin D3 synthesis in the skin |

(145-147,159,160) |

| Decreased bioavailability Diet: Limited intake of natural and fortified foods with vitamin D, lack of supplementation Malabsorption: Intestinal malabsorption syndromes (cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease and short bowel syndrome); bile acid sequestrants (colestipol and cholestyramine) and lipase inhibitors (orlistat) Obesity: Volumetric dilution of vitamin D in the compartments that are increased in obesity (serum, muscle, liver and adipose tissue) |

Decreased bioavailability of 25(OH)D Decreased ability to absorb vitamin D Decreased bioavailability of 25(OH)D |

(58,148,161,162) |

| Increased catabolism Drugs: Glucocorticoid and antiepileptic treatment |

1,25(OH)2D degradation due to increased 24-OHase activity. These drugs may increase the expression of 24-OHase through the activation of the pregnane X receptor |

(152-154) |

| Decreased synthesis of 25(OH)D Liver failure: Chronic liver disease |

Decreased hydroxylation of vitamin D resulting in low levels of 25(OH)D | (149) |

| Increased urinary loss of 25(OH)D Nephrotic syndrome: 25(OH)D bound to DBP is lost in the urine |

Significant loss of 25(OH)D in urine due to proteinuria | (150,151) |

| Decreased synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D Chronic kidney disease: Decreased renal mass limits the amount of CYP27B1; decreased glomerular filtration rate may limit delivery of substrate to the CYP27B1 |

Progressive decrease in 1,25(OH)2D during the course of kidney disease | (155,156) |

| Genetic polymorphisms Single nucleotide polymorphisms at DHCR7 (rs7944926), GC (rs2282679), CYP2R1 (rs10741657), CYP27B1 (rs10877012) and VDR (rs2228570) |

Low serum 25(OH)D concentrations and less effective transcriptional activation of VDR | (157,158) |

Adapted from ref. (62). UV-B, ultraviolet-B; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; 24-OHase, 25-hydroxyvitamin D-24-hydroxylase; DBP, vitamin D-binding protein; VDR, vitamin D receptor.

9. Vitamin D deficiency in Latin America: A paradox of the tropical zone

As aforementioned, in addition to latitude, various factors influence vitamin D levels in the human body (62). Therefore, the Latin American population, the vast majority of which resides in the tropical zone, is not exempt from vitamin D deficiency (70). Vitamin D insufficiency in this region may be a public health problem; however, despite studies that report 25(OH)D deficiencies in the Latin American population, it is impossible to establish the magnitude of the problem due to the lack of nationally representative data (35). Table III summarizes the most recent reports on the status of 25(OH)D in the population of Latin American countries that are among the top 10 countries by confirmed cases and deaths from COVID-19 globally (18,163-167). Although the definition of serum 25(OH)D status varies among the studies, the majority of these reports align with the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (168) and the Endocrine Society (169): Vitamin D deficiency is defined as serum levels of 25(OH)D <20 ng/ml (<50 nmol/l), and vitamin D insufficiency is defined as serum levels between 21 ng/ml (52.5 nmol/l) and 29 ng/ml (72.5 nmol/l). Of note, the IOM suggests that 25(OH)D levels >20 ng/ml (>50 nmol/l) are sufficient to meet the needs of ~98% of the population; however, this recommendation mainly considers the maintenance of bone health (168).

Table III.

Serum concentration of 25(OH)D in some Latin American countries.

| Country | Age group | Age (years) | N | Mean 25(OH)D, ng/ml | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | Adults | 39.8±10.9 | 572 | 23.2±5.9 | (163) |

| Mexico | Adults | 57.8±16.6 | 117 | 18.4±7.2 | (164) |

| Peru | Adolescents | 14.9±0.8 | 1,441 | 25.3 (rangeb, 73.1) | (165) |

| Chile | Adult women Older women |

35.4±8.5 73.6±6.6 |

1,245 686 |

20.2±8.0 18±8.5 |

(166) |

| Colombia | Adults | 57a (rangeb, 24.0) | 1,339 | 32.3a(rangeb, 23.2) | (167) |

Median.

Difference between the minimum and maximum value; specific values are not available in the original study. 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D. 1 ng/ml=2.5 nmol/l.

10. Vitamin D supplementation for infection prevention

Various factors cause a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency. However, although latitude and season are key factors, certain countries with long winters report lower rates of deficiency compared with those in countries in the tropical zone; this may be due to food fortification, high consumption of fatty fish and supplementation (170). Therefore, although the recommendations for restoring the levels of vitamin D include the consumption of foods rich in vitamin D and increased sun exposure, considering the difficulty of generalized access to foods such as fish, clothing habits and the avoidance of sunlight, supplementation may represent an effective strategy (58). Furthermore, the recommendation of vitamin D supplementation may not only help prevent low concentrations of 25(OH)D and improve bone health, but may also be useful for the prevention of complications following infection with SARS-CoV-2 (57).

Regarding the recommendations for vitamin D intake, these may vary between populations. The IOM recommends daily consumption of 600 IU (15 μg) for children >1 year and adults ≤70 years (168). Similarly, the European Food Safety Authority recommends a daily intake of 600 IU (15 μg), with a maximum intake of 4,000 IU/day (100 μg) in healthy adults (171,172). The UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition recommends vitamin D intake of 400 IU/day (10 μg) for everyone in the general population >4 years (173), whereas the European Food Safety Agency has reported that vitamin D doses of ≤10,000 IU/day (≤250 μg) are safe if there are no comorbidities (171,172). Other reports indicate that doses ≤6,000 IU/day (≤150 μg) are necessary to achieve serum 25(OH)D concentrations >40 ng/ml (100 nmol/l). Doses of ≤15,000 IU/day (≤375 μg) have also been reported to be safe and effective for rapidly increasing 25(OH)D concentrations (174). The Brazilian Society of Endocrinology and Metabology (175) and the Ministry of Health of the Government of Chile (176) adhere to the recommendations indicated by the IOM. In colombia, the colombian consensus on Vitamin D recommends an intake of ≤2,000 IU/day (≤50 μg) in cases of insufficiency, and ≤6,000 IU/day (≤150 μg) in deficiency (177). The suggested daily intake in Mexico is only 224 IU (5.6 μg), as there are currently no studies demonstrating the need to supplement vitamin D in the Mexican population (178).

Supplementation with vitamin D may be necessary for individuals with deficiency to achieve a sufficient concentration of 25(OH)D, which is >30 ng/ml (75 nmol/l), even with consumption of fortified foods, since it is difficult to maintain this concentration with food alone (179). An international consensus for the recommended daily intake for vitamin D would be useful; however, considering that vitamin D deficiency is an undoubted global problem, that there is a lack of clinical trials that accurately indicate the appropriate dose of vitamin D supplementation. Due to the need to establish accessible strategies for the prevention of complications from COVID-19, the authors of the present review agree with the current proposal of Grant et al (180), who suggested that individuals with low levels of 25(OH)D should be supplemented for a month with 10,000 IU/day (250 μg) of vitamin D3 for the rapid restoration of the desired concentrations between 40 and 60 ng/ml (100 and 150 nmol/l). For maintenance, this should be followed by daily supplementation of 5,000 IU (125 μg).

Notably, that baseline monitoring of 25(OH)D concentrations should be considered. In addition, avoiding high doses of calcium and assessing the consumption of magnesium and vitamin K2 should be considered for the prevention of long-term adverse effects of high doses of vitamin D (180,181).

11. Conclusions

The lack of effective therapies and the uncertainty of universal access to possible vaccines for COVID-19 demand alternatives with potential immunomodulatory effects such as vitamin D supplementation, which may contribute to the prevention of respiratory infections and their complications. However, it is necessary to await the results of the undergoing clinical trials and to continue with the execution of further studies to determine the effects of vitamin D supplementation on COVID-19 and establish the ideal dosage. Observational studies appear to demonstrate an association between low vitamin D concentrations and susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, it is also vital to carry out national and international studies to determine the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Latin America. The authors of the present study call on the corresponding authorities to assess the fortification with vitamin D of foods for daily consumption, since supplementation may represent a difficulty for individuals with a low income.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT Ciencia Básica; grant no. A1-S-8774) and Universidad de Guadalajara through the 'Fortalecimiento de la Investigatión y el Posgrado 2020' fund.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

FJTH, and JFMV conceived, drafted, and finalized the manuscript. JFMV, GASZ, GGE, JHB, and GMO critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.da Costa VG, Moreli ML, Saivish MV. The emergence of SARS, MERS and novel SARS-2 coronaviruses in the 21st century. Arch Virol. 2020;165:1517–1526. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee C. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: An emerging and re-emerging epizootic swine virus. Virol J. 2015;12:193. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0421-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bande F, Arshad SS, Bejo MH, Moeini H, Omar AR. Progress and challenges toward the development of vaccines against avian infectious bronchitis. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:424860. doi: 10.1155/2015/424860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouchier RA, Kuiken T, Schutten M, van Amerongen G, van Doornum GJ, van den Hoogen BG, Peiris M, Lim W, Stohr K, Osterhaus AD. Aetiology: Koch's postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature. 2003;423:240. doi: 10.1038/423240a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Timeline of WHO's response to COVID-19. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrosillo N, Viceconte G, Ergonul O, Ippolito G, Petersen E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: Are they closely related? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu K, Fang YY, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang MF, Ma JP, Xiao W, Wang YN, Zhong MH, Li CH, et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:1025–1031. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang S, Mao Y, Jones RM, Tan Q, Ji JS, Li N, Shen J, LV Y, Pan L, Ding P, et al. Aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2? Evidence, prevention and control. Environ Int. 2020;144:106039. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, Romero-Severson E, Hengartner N, KE R. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1470–1477. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauch CT, Lloyd-Smith JO, Coffee MP, Galvani AP. Dynamically modeling SARS and other newly emerging respiratory illnesses: Past, present, and future. Epidemiology. 2005;16:791–801. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181633.80269.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281–292.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou X, Chen K, Zou J, Han P, Hao J, Han Z. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front Med. 2020;14:185–192. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0754-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, Zhao J, Liu H, Peng J, Li Q, Jiang C, Zhou Y, Liu S, et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e16–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters R, Ee N, Peters J, Beckett N, Booth A, Rockwood K, Anstey KJ. Common risk factors for major noncommunicable disease, a systematic overview of reviews and commentary. The implied potential for targeted risk reduction. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019 Oct 15; doi: 10.1177/2040622319880392. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cena H, Calder PC. Defining a healthy diet: Evidence for the role of contemporary dietary patterns in health and disease. Nutrients. 2020;12:334. doi: 10.3390/nu12020334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu D, Lewis ED, Pae M, Meydani SN. Nutritional modulation of immune function. Analysis of evidence, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Front Immunol. 2019;9:3160. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forsyth C, Kouvari M, D'Cunha NM, Georgousopoulou EN, Panagiotakos DB, Mellor DD, Kellett J, Naumovski N. The effects of the Mediterranean diet on rheumatoid arthritis prevention and treatment. A systematic review of human prospective studies. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:737–747. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng R, Gonzalez A, Yue J, Wu X, Qiu M, Gui L, Zhu S, Huang L. Efficacy and safety of vitamin D supplementation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med Sci. 2019;358:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee KR, Midgette Y, Shah R. Fish oil derived omega 3 fatty acids suppress adipose NLRP3 inflammasome signaling in human obesity. J Endocr Soc. 2018;3:504–515. doi: 10.1210/js.2018-00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hussain MI, Ahmed W, Nasir M, Mushtaq MH, Sheikh AA, Shaheen AY, Mahmood A. Immune boosting role of vitamin E against pulmonary tuberculosis. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2019;32(Suppl 1):S269–S276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Estevez NS, Alvarez-Guevara AN, Rodriguez-Martinez CE. Effects of zinc supplementation in the prevention of respiratory tract infections and diarrheal disease in Colombian children. A 12-month randomised controlled trial. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2016;44:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Yeh C, Jin Z, Ding L, Liu BY, Zhang L, Dannelly HK. Prospective study of probiotic supplementation results in immune stimulation and improvement of upper respiratory infection rate. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2018;3:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarthy MS, Martindale RG. Immunonutrition in critical illness. What is the role? Nutr Clin Pract. 2018;33:348–358. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chow O, Barbul A. Immunonutrition. Role in wound healing and tissue regeneration. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014;3:46–53. doi: 10.1089/wound.2012.0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilz S, Zittermann A, Trummer C, Theiler-Schwetz V, Lerchbaum E, Keppel MH, Grübler MR, März W, Pandis M. Vitamin D testing and treatment. A narrative review of current evidence. Endocr Connect. 2019;8:R27–R43. doi: 10.1530/EC-18-0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Hooper RL, Greenberg L, Aloia JF, Bergman P, Dubnov-Raz G, Esposito S, Ganmaa D, Ginde AA, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections. Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nair R, Maseeh A, Vitamin D. The 'sunshine' vitamin. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2012;3:118–126. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.95506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roth DE, Abrams SA, Aloia J, Bergeron G, Bourassa MW, Brown KH, Calvo MS, Cashman KD, Combs G, De-Regil LM, et al. Global prevalence and disease burden of vitamin D deficiency: A roadmap for action in low- and middle-income countries. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2018;1430:44–79. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brito A, Cori H, Olivares M, Fernanda Mujica M, Cediel G, Lopez de Romana D. Less than adequate vitamin D status and intake in Latin America and the Caribbean. A problem of unknown magnitude. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34:52–64. doi: 10.1177/156482651303400107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren LL, Wang YM, Wu ZQ, Xiang ZC, Guo L, Xu T, Jiang YZ, Xiong Y, Li YJ, Li XW, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: A descriptive study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:1015–1024. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Moore M J, Vasilieva N, Sui J, Wong S K, Berne M A, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Greenough TC, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jia HP, Look DC, Shi L, Hickey M, Pewe L, Netland J, Farzan M, Wohlford-Lenane C, Perlman S, McCray PB., Jr ACE2 receptor expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection depend on differentiation of human airway epithelia. J Virol. 2005;79:14614–14621. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14614-14621.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rabi FA, Al Zoubi MS, Kasasbeh GA, Salameh DM, Al-Nasser AD. SARS-CoV-2 and coronavirus disease 2019: What we know so far. Pathogens. 2020;9:231. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuki K, Fujiogi M, Koutsogiannaki S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: A review. Clin Immunol. 2020;215:108427. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banu N, Panikar SS, Leal LR, Leal AR. Protective role of ACE2 and its downregulation in SARS-CoV-2 infection leading to macrophage activation syndrome: Therapeutic implications. Life Sci. 2020;256:117905. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Geng M, Peng Y, Meng L, Lu S. Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19. J Pharm Anal. 2020;10:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nile SH, Nile A, Qiu J, Li L, Jia X, Kai G. COVID-19: Pathogenesis, cytokine storm and therapeutic potential of interferons. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020;53:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burki T. COVID-19 in Latin America. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:547–548. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30303-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolano-Ortiz TR, Camargo-Caicedo Y, Puliafito SE, Ruggeri MF, Bolano-Diaz S, Pascual-Flores R, Saturno J, Ibarra-Espinosa S, Mayol-Bracero OL, Torres-Delgado E, Cereceda-Balic F. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 through Latin America and the Caribbean region: A look from its economic conditions, climate and air pollution indicators. Environ Res. 2020;191:109938. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organization Our World in Data: Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guzman-Holst A, DeAntonio R, Prado-Cohrs D, Juliao P. Barriers to vaccination in Latin America: A systematic literature review. Vaccine. 2020;38:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pathak DSK, Salunke DAA, Thivari DP, Pandey A, Nandy DK, Harish VK, Ratna D, Pandey DS, Chawla DJ, Mujawar DJ, Dhanwate DA, Menon DV. No benefit of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19: Results of systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials'. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:1673–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, Liu W, Wang J, Fan G, Ruan L, Song B, Cai Y, Wei M, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Novartis: Novartis provides update on CAN-COVID trial in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and cytokine release syndrome (CRS) 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanofi: Sanofi provides update on Kevzara® (sarilumab) Phase 3 trial in severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients outside the U.S. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 52.AstraZeneca: Update on CALAVI phase II trials for calquence in patients hospitalised with respiratory symptoms of COVID-19. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iserson KV. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) vaccine development and production: An ethical way forward. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2021;30:59–68. doi: 10.1017/S096318012000047X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bollyky TJ, Gostin LO, Hamburg MA. The equitable distribution of COVID-19 therapeutics and vaccines. JAMA. 2020;323:2462–2463. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barreto SM, Miranda JJ, Figueroa JP, Schmidt MI, Munoz S, Kuri-Morales PP, Silva JB., Jr Epidemiology in Latin America and the Caribbean: Current situation and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:557–571. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zumla A, Hui DS, Azhar EI, Memish ZA, Maeurer M. Reducing mortality from 2019-nCoV: Host-directed therapies should be an option. Lancet. 2020;395:e35–e36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30305-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rhodes JM, Subramanian S, Laird E, Kenny RA. Editorial: Low population mortality from COVID-19 in countries south of latitude 35 degrees North supports vitamin D as a factor determining severity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:1434–1437. doi: 10.1111/apt.15777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lamberg-Allardt C. Vitamin D in foods and as supplements. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;92:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeon SM, Shin EA. Exploring vitamin D metabolism and function in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:20. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bikle DD. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem Biol. 2014;21:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Christakos S, Dhawan P, Verstuyf A, Verlinden L, Carmeliet G. Vitamin D: Metabolism, molecular mechanism of action, and pleiotropic effects. Physiol Rev. 2016;96:365–408. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bivona G, Agnello L, Ciaccio M. The immunological implication of the new vitamin D metabolism. Cent J Immunol. 2018;43:331–334. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2018.80053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Charoenngam N, Holick MF. Immunologic effects of vitamin d on human health and disease. Nutrients. 2020;12:2097. doi: 10.3390/nu12072097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ghebrehewet S, MacPherson P, Ho A. Influenza. BMJ. 2016;355:i6258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tamerius JD, Shaman J, Alonso WJ, Bloom-Feshbach K, Uejio CK, Comrie A, Viboud C. Environmental predictors of seasonal influenza epidemics across temperate and tropical climates. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003194. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arbeitskreis Blut, Untergruppe 'Bewertung Blutassoziierter Krankheitserreger': Influenza virus. Transfus Med Hemother. 2009;36:32–39. doi: 10.1159/000197314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hope-simpson RE. The role of season in the epidemiology of influenza. J Hyg (Lond) 1981;86:35–47. doi: 10.1017/S0022172400068728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cannell JJ, Vieth R, Umhau JC, Holick M F, Grant WB, Madronich S, Garland CF, Giovannucci E. Epidemic influenza and vitamin D. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:1129–1140. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mendes MM, Hart KH, Botelho PB, Lanham-New SA. Vitamin D status in the tropics: Is sunlight exposure the main determinant? Nutr Bull. 2018;43:428–434. doi: 10.1111/nbu.12349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huotari A, Herzig KH. Vitamin D and living in northern latitudes-an endemic risk area for vitamin D deficiency. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67:164–178. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v67i2-3.18258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kmiec P, Zmijewski M, Waszak P, Sworczak K, Lizakowska-Kmiec M. Vitamin D deficiency during winter months among an adult, predominantly urban, population in Northern Poland. Endokrynol Pol. 2014;65:105–113. doi: 10.5603/EP.2014.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kmiec P, Zmijewski M, Lizakowska-Kmiec M, Sworczak K. Widespread vitamin D deficiency among adults from northern Poland (54°N) after months of low and high natural UVB radiation. Endokrynol Pol. 2015;66:30–38. doi: 10.5603/EP.2015.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kroll MH, Bi C, Garber CC, Kaufman HW, Liu D, Caston-Balderrama A, Zhang K, Clarke N, Xie M, Reitz RE, et al. Temporal relationship between vitamin D status and parathyroid hormone in the United States. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Greene-Finestone LS, Berger C, de Groh M, Hanley DA, Hidiroglou N, Sarafin K, Poliquin S, Krieger J, Richards JB, Goltzman D, CaMos Research Group 25-Hydroxyvitamin D in canadian adults: Biological, environmental, and behavioral correlates. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1389–1399. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1362-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Steel J, Palese P. Influenza virus transmission is dependent on relative humidity and temperature. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1470–1476. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lowen Ac, Steel J. Roles of humidity and temperature in shaping influenza seasonality. J Virol. 2014;88:7692–7695. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03544-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pham H, Rahman A, Majidi A, Waterhouse M, Neale RE. Acute respiratory tract infection and 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3020. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ilie PC, Stefanescu S, Smith L. The role of vitamin D in the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 infection and mortality. Aging clin Exp Res. 2020;32:1195–1198. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hastie CE, Mackay DF, Ho F, Celis-Morales CA, Katikireddi SV, Niedzwiedz CL, Jani BD, Welsh P, Mair FS, Gray SR, et al. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.D'Avolio A, Avataneo V, Manca A, Cusato J, De Nicolo A, Lucchini R, Keller F, Cantù M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are lower in patients with positive PcR for SARS-coV-2. Nutrients. 2020;12:1359. doi: 10.3390/nu12051359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meltzer DO, Best TJ, Zhang H, Vokes T, Arora V, Solway J. Association of vitamin D deficiency and treatment with cOVID-19 incidence. MedRxiv. 2020 2020.05.08.20095893. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Whittemore PB. COVID-19 fatalities, latitude, sunlight, and vitamin D. Am J Infect control. 2020;48:1042–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Panagiotou G, Tee SA, Ihsan Y, Athar W, Marchitelli G, Kelly D, Boot CS, Stock N, Macfarlane J, Martineau AR, et al. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels in patients hospitalized with cOVID-19 are associated with greater disease severity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2020;93:508–511. doi: 10.1111/cen.14276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Merzon E, Tworowski D, Gorohovski A, Vinker S, Golan Cohen A, Green I, Frenkel Morgenstern M. Low plasma 25(OH) vitamin D level is associated with increased risk of COVID-19 infection: An Israeli population-based study. FEBS J. 2020;287:3693–3702. doi: 10.1111/febs.15495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Batur LK, Hekim N. The role of DBP gene polymorphisms in the prevalence of new coronavirus disease 2019 infection and mortality rate. J Med Virol. 2020 Aug 8; doi: 10.1002/jmv.26409. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carpagnano GE, Di Lecce V, Quaranta VN, Zito A, Buonamico E, Capozza E, Palumbo A, Di Gioia G, Valerio VN, Resta O. Vitamin D deficiency as a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020 Aug 9; doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01370-x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Abrishami A, Dalili N, Mohammadi Torbati P, Asgari R, Arab-Ahmadi M, Behnam B, Sanei-Taheri M. Possible association of vitamin D status with lung involvement and outcome in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective study. Eur J Nutr. 2020 Oct 30; doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02411-0. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.De Smet D, De Smet K, Herroelen P, Gryspeerdt S, Martens GA. Serum 25(OH)D level on hospital admission associated with COVID-19 stage and mortality. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020 Nov 25; doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa252. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ling SF, Broad E, Murphy R, Pappachan JM, Pardesi-Newton S, Kong MF, Jude EB. High-dose cholecalciferol booster therapy is associated with a reduced risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19: A cross-sectional multi-centre observational study. Nutrients. 2020;12:3799. doi: 10.3390/nu12123799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Faniyi AA, Lugg ST, Faustini SE, Webster C, Duffy JE, Hewison M, Shields A, Nightingale P, Richter AG, Thickett DR. Vitamin D status and seroconversion for COVID-19 in UK healthcare workers. Eur Respir J. 2020 Dec 10; doi: 10.1183/13993003.04234-2020. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ye K, Tang F, Liao X, Shaw B A, Deng M, Huang G, Qin Z, Peng X, Xiao H, Chen C, et al. Does serum vitamin D level affect COVID-19 infection and its severity?-A case-control study. J Am Coll Nutr. 2020 Oct 13; doi: 10.1080/07315724.2020.1826005. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jain A, Chaurasia R, Sengar NS, Singh M, Mahor S, Narain S. Analysis of vitamin D level among asymptomatic and critically ill COVID-19 patients and its correlation with inflammatory markers. Sci Rep. 2020;10:20191. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77093-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cereda E, Bogliolo L, Klersy C, Lobascio F, Masi S, Crotti S, De Stefano L, Bruno R, Corsico AG, Di Sabatino A, et al. Vitamin D 25OH deficiency in COVID-19 patients admitted to a tertiary referral hospital. Clin Nutr. 2020 Nov 2; doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.10.055. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Annweiler C, Hanotte B, Grandin de l'Eprevier C, Sabatier JM, Lafaie L, Célarier T. Vitamin D and survival in COVID-19 patients: A quasi-experimental study. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;204:105771. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Annweiler G, Corvaisier M, Gautier J, Dubée V, Legrand E, Sacco G, Annweiler C. Vitamin D supplementation associated to better survival in hospitalized frail elderly COVID-19 patients: The GERIA-COVID Quasi-experimental study. Nutrients. 2020;12:3377. doi: 10.3390/nu12113377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Entrenas Castillo M, Entrenas Costa LM, Vaquero Barrios JM, Alcala Diaz JF, Lopez Miranda J, Bouillon R, Quesada Gomez JM. 'Effect of calcifediol treatment and best available therapy versus best available therapy on intensive care unit admission and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: A pilot randomized clinical study'. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;203:105751. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rastogi A, Bhansali A, Khare N, Suri V, Yaddanapudi N, Sachdeva N, Puri GD, Malhotra P. Short term, high-dose vitamin D supplementation for COVID-19 disease: A randomised, placebo-controlled, study (SHADE study) Postgrad Med J. 2020 Nov 12; doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139065. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pereira M, Dantas Damascena A, Galvâo Azevedo LM, de Almeida Oliveira T, da Mota Santana J. Vitamin D deficiency aggravates COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020 Nov 4; doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1841090. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu N, Sun J, Wang X, Zhang T, Zhao M, Li H. Low vitamin D status is associated with coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shoenfeld Y, Giacomelli R, Azrielant S, Berardicurti O, Reynolds JA, Bruce IN. Vitamin D and systemic lupus erythe-matosus-the hype and the hope. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cantorna MT, Snyder L, Lin YD, Yang L. Vitamin D and 1,25(OH)2D regulation of T cells. Nutrients. 2015;7:3011–3021. doi: 10.3390/nu7043011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang YG, Wu S, Sun J. Vitamin D, vitamin D receptor, and tissue barriers. Tissue Barriers. 2013;1:e23118. doi: 10.4161/tisb.23118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ware LB, Matthay MA. Alveolar fluid clearance is impaired in the majority of patients with acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Git care Med. 2001;163:1376–1383. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.2004035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]