Abstract

Objectives:

Previous analyses of interventions targeting relationships between family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias and residential long-term care (RLTC) staff showed modest associations with caregiver outcomes. This analysis aimed to better understand interpersonal and contextual factors that influence caregiver–staff relationships and identify targets for future interventions to improve these relationships.

Methods:

Using a parallel convergent mixed methods approach to analyze data from an ongoing counseling intervention trial, descriptive statistics characterized the sample of 85 caregivers and thematic analyses explored their experiences over 4 months.

Results:

The findings illustrated that communication, perceptions of care, and relationships with staff are valued by family caregivers following the transition of a relative with dementia to RLTC.

Discussion:

The findings deepen understanding of potential intervention targets and mechanisms. These results can inform future psychosocial and psychoeducational approaches that assist, validate, and empower family caregivers during the transition to RLTC.

Keywords: residential long-term care, family caregiver, care recipient, transitions, dementia

Introduction

As the population of older adults grows, so too will the number of new and existing cases of dementia. By 2050, an estimated 13.8 million Americans aged 65 and older will have Alzheimer’s dementia compared to 5.8 million in 2020 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). Current estimates indicate that 30% of Americans with dementia live in residential long-term care (RLTC) such as nursing homes, assisted living, and group homes (Lepore et al., 2017). In RLTC, 42 to 48% of residents have Alzheimer’s or other dementias (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016) and 70% of residents had some form of cognitive impairment (Zimmerman et al., 2014). People with dementia living in the community often rely on family members for care, and moving to RLTC does not eliminate family caregiving responsibilities (Kemp, 2012; Williams et al., 2012). Instead, family involvement in care often pivots from activity of daily living care to responsibility for care coordination, health care decisions, and financing (Gaugler & Kane, 2007; Gaugler et al., 2020). Kemp et al. (2013) theorized that family caregivers are integral members of assisted living of each resident’s convoy of care, providing support and enhancing care. Researchers have also found that family involvement in RLTC may be positively associated with residents’ quality of care and quality of life (Barken & Lowndes, 2018; Gaugler et al., 2004; Kiely et al., 2000; Penrod et al., 2000).

Cooperative family and staff relationships are essential to creating a positive RLTC environment for the person living with dementia and fostering family caregiver adjustment (Bauer & Nay, 2011; Bauer et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2007; Garity, 2006; Gaugler et al., 2014; Kemp et al., 2013; Ryan & McKenna, 2015). Prior qualitative and quantitative literature has explored various elements associated with caregiver and staff relationships, including communication, conflict, stress, and caregiver experiences with RLTC (Chen et al., 2007; Gladstone & Wexler, 2002; Hertzberg & Ekman, 2000; Jacobson et al., 2015; Utley-Smith et al., 2009). Studies have shown that when family caregivers and staff have reciprocal communication, well-defined roles, and cooperative relationships, resident care and quality of life ratings as well as caregiver satisfaction improve (Haesler et al., 2007; Roberts & Ishler, 2018; Robison et al., 2007).

Researchers have also examined the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve family and staff relationships by promoting cooperative communication (Pillemer et al., 1998), partnership agreements (Maas et al., 2004), or well-defined caregiving roles (Zimmerman et al., 2013), respectively. Results of these interventions found modest effects on family caregiver outcomes. Additionally, researchers conducting a review of interventions focused on improving caregiver adjustment after their care recipient moved to RLTC found mixed results: decreases in caregiver distress and guilt but no effects on satisfaction with the care community were apparent (Brooks et al., 2018). To inform more effective interventions for family caregivers, research is needed to better delineate the dynamics of caregiver and staff relationships, determine influential community features, and discern the clinical mechanisms of interventions that target improved relationships with staff, satisfaction with the RLTC, and caregiver adjustment.

Although previous qualitative and quantitative research contributed knowledge of factors that impact communication and collaboration between family and community staff, the current study explored a much broader array of factors related to caregiver adjustment to RLTC through a descriptive analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data from the multicomponent Residential Care Transition Module (RCTM) intervention. The primary aim of the RCTM is to help family caregivers adjust to their new caregiving roles following their care recipient’s move to a RLTC setting for memory concerns (Gaugler et al., 2015, 2020). The RCTM focuses not only on the caregiver’s relationship and communication with staff but also on personal factors such as stress management and self-efficacy as well as external factors that may influence the caregiver’s experience such as finances and location as proposed by Kemp’s theory on convoy of care (Kemp et al., 2013). The present study used a mixed methods approach to examine: (1) common themes that emerged during counseling related to caregivers’ multifaceted experiences with RLTC communities and staff; (2) how counseling can provide practical and potentially effective support for caregivers after they transition a family member to RLTC; and (3) clinical implications and practical recommendations for RLTC communities and staff.

Transition to Residential Care Conceptual Model

The development of the RCTM was informed by the Stress Process Model for Residential Care (SPM-RC), which is an extension of the SPM for dementia caregiving (Pearlin et al., 1990; Whitlatch et al., 2001).

The SPM-RC theorizes that as stress accumulates, it proliferates to other life domains and in turn affects mental and/or physical health. As highlighted in Figure 1, the SPM-RC applies this framework to the RLTC setting with the inclusion of primary stressors characterizing dementia severity, which results in secondary role strain (operationalized as caregivers’ and care recipients’ adjustment to RLTC) and residential care-specific stressors (in bold). We have focused on role strain and residential care-specific stressors in this analysis. Of particular importance to this analysis are placement-related residential care stressors which include establishing effective relationships with community staff, maintaining or improving care recipient quality of life, and advocating for the care recipient’s needs (Bramble et al., 2009; Sury et al., 2013). In this study, we sought to characterize known residential care stressors and identify additional factors related to communities and staff that affected caregivers after moving a family member into residential care to identify targets for clinical intervention.

Figure 1.

Simplified Stress Process Model for Residential Care.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a mixed methods analysis of an ongoing parallel randomized controlled trial (RCT) assessing the RCTM, a counseling intervention designed to support families of persons with dementia following placement in RLTC. For this study, RLTC included nursing homes, assisted living communities, and care homes. In brief, the study recruited family caregivers who had admitted a relative with a physician-diagnosed dementia to a RLTC setting. Family caregivers were recruited from across the US through LeadingAge and advertisements in local newspapers as well as the University of Minnesota Caregiver Registry and StudyFinder. Family caregivers were required to be English speaking, over 21 years of age, and not participating in individual or group counseling related to caregiving. After providing written consent and completing a baseline survey, caregivers were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio in blocks of six to 10 using a random number generator to either the RCTM (n = 120) or a usual care control condition (n = 120) by the study co-ordinator. Randomization was stratified by the caregiver relationship to the care recipient (spouse vs. child) and time since entry to RLTC (less than vs. greater than 3 months).

Trained transition counselors (TCs) provide six individualized sessions by phone or secure Web-based video conferencing to members of the intervention group during a 4-month period. Other family members were also included in the counseling sessions based on the needs expressed by the primary caregiver. The first three sessions were held weekly and the final three sessions were held monthly. Follow-up surveys were administered by blinded graduate research assistants four, eight, and 12 months after enrollment. When a care recipient died during the study follow-up, the caregiver was administered a shortened bereavement survey. The study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (UMNIRB; #1511S80406). Detailed information on the RCTM intervention and study design is available elsewhere (Gaugler et al., 2020).

Sample

For this analysis we included all primary caregivers in the treatment group who completed baseline and 4-month surveys as of April 15, 2019 (n = 85). Eleven caregivers experienced the bereavement of a care recipient during follow-up resulting in administration of a shortened survey without selected measures and a reduced sample size (n = 74) for several measures. We focused on the first 4 months of follow-up because it overlapped with the six structured counseling sessions.

Counseling Process

The RCTM counseling intervention provided support and skill-building activities to assist family caregivers in adjusting to changes and stressors following the admission of their relative into a RLTC community. Among the objectives for each session were the caregiver’s acquisition of information and strategies designed to deal with their unique caregiving situation. The sessions were designed to establish a therapeutic rapport between the TC and the caregiver, provide a safe environment to explore stressors, examine family relational dynamics as they pertain the RLTC placement decision itself as well as the roles that different family members play in the life of the caregiver and care recipient, identify new modes of communication to facilitate more effective interactions with other family members and community staff, and identify effective ways to advocate for improved quality of care and quality of life for their care recipient (Gaugler et al., 2020).

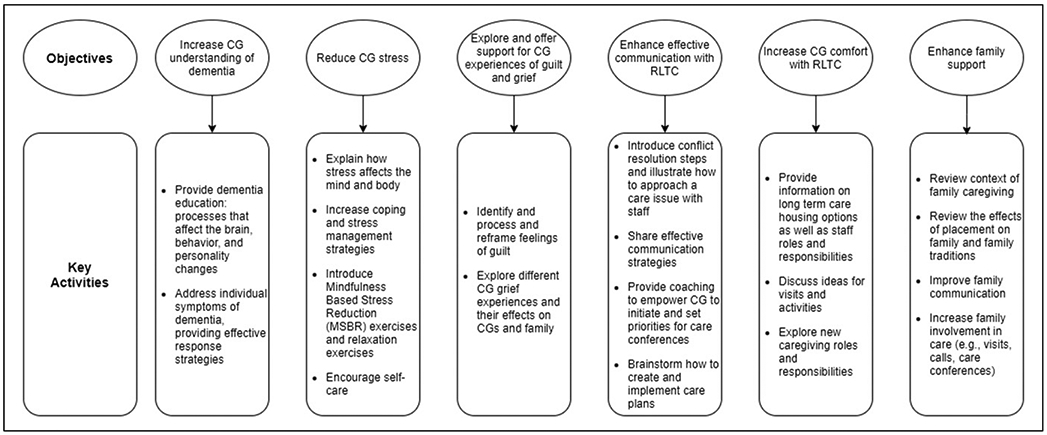

The RCTM is a semi-structured individualized intervention, allowing caregivers to choose which session topics they would like to discuss and when. There were several predetermined RCTM session topics offered to caregivers that correspond to the objectives of the intervention, such as communication and problem-solving, conflict resolution, and stress management (Figure 2). In addition to the six sessions, the TC was available to the caregiver throughout their time in the study for ad hoc contact or counseling sessions as requested by the caregiver.

Figure 2.

Main objectives and key activities of residential care transition module intervention.

The study included two TCs; Tamara L Statz (TLS) was hired approximately 1 year prior to Robyn Birkeland (RB). Upon randomization, caregivers were assigned to a TC on an alternate basis to balance their caseloads. Each TC had approximately 20 active treatment participants at any given time period with an additional 20 treatment participants receiving ad hoc sessions or quarterly check-in calls.

Caregivers rarely raised issues related to abuse or neglect. When such concerns did occur, they were discussed at length with the TC, as the TC is a mandated reporter in the state of Minnesota. Depending on details of the situation, a plan was made for the caregiver to advocate at the community, contact the local ombudsman (TC provided the contact information), or the local department of health. In cases of imminent danger, the caregiver would be advised to call the police.

Data

We utilized data from baseline and 4-month surveys to assess secondary role strain and residential care stress. Baseline surveys also included demographic information of the caregiver and care recipient including age, race/ethnicity, relationship between the caregiver and the care recipient, and the length and severity of the care recipients’ memory problems. Secondary role stress was ascertained using a pair of Likert scale items in which caregivers rated their own and their care recipient’s level of adjustment to the RLTC setting. Residential care stress was assessed with a series of measures developed by Whitlatch et al., 2001: (1) perceptions of staff communication with residents’ families, (2) perceptions of staff support for families, and (3) the number of positive and negative interactions between caregivers and community staff. The Family Involvement Interview characterized caregiver involvement in the life of the care recipient in the RLTC setting. Residential care stress measures were sums of dichotomous items where higher counts indicated a greater number of affirmative items.

Qualitative data were obtained from counseling session case notes (Gaugler et al., 2020). Case notes consisted of key caregiving topics addressed, family dynamics, intervention components provided by TC, verbatim quotes, caregiver’s reaction to the session, topics to address during the next session, and counselor impressions. Counselors took detailed case notes during sessions which enabled use of direct caregiver quotes in qualitative analysis. The case note form was designed during the pilot phase of the study by Joseph Gaugler (JG) and the pilot phase TC. The pilot phase TC trained TLS on the case note form who subsequently trained RB to create consistent notes. Only JG, TLS, and RB were involved in the structure and content of the notes. A total of 1438 pages of case notes were included in this analysis.

Analysis

We conducted a parallel convergent mixed methods analysis (Creswell, 2007). Quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed simultaneously but separately. Quantitative survey data provided context for understanding the study population, and detailed case notes provided in-depth qualitative data on individual caregiver experiences with communities and staff. Results were interpreted side by side to determine points of convergence and divergence and are presented in the Discussion.

Quantitative analysis.

We characterized secondary role stressors and residential care stress at baseline and 4 months. We also examined individual questions within the measures, chosen a priori, to reflect objectives of the RCTM intervention (Table 2). We categorized caregivers and care recipients as reporting high (good or very good/excellent) and low (very poor/poor or fair) adjustment to RLTC based on the median reported scores. We used t-test and chi-square tests to examine baseline differences by adjustment level.

Table 2.

Stressors at Baseline and 4 months

| Baseline |

4 Months |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLTC stressor measures | M | SD | M | SD | p |

| Perceptions of staff communication | 12.3 | 2.7 | 13.0 | 2.5 | ** |

| Staff support | 10.3 | 2.8 | 10.4 | 2.7 | |

| Positive interactions | 3.3 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 1.3 | * |

| Negative interactions | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | * |

| Secondary role stressors | N | % | N | % | |

| CR adjustment | |||||

| Very poor/Poor | 6 | 7.1 | 6 | 8.0 | |

| Fair | 35 | 41.2 | 29 | 38.7 | |

| Good | 34 | 40.0 | 28 | 37.3 | |

| Very good/Excellent | 10 | 11.8 | 12 | 16.0 | |

| CG adjustment | |||||

| Very poor/Poor | 3 | 3.7 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Fair | 31 | 41.2 | 25 | 35.2 | |

| Good | 27 | 40.0 | 34 | 47.9 | |

| Very good/Excellent | 20 | 11.8 | 11 | 15.5 | |

| RLTC stressor items | N | % | N | % | |

| Perceptions of staff communication | |||||

| How often do direct care workers (e.g., nursing assistants) in your relative’s facility: | |||||

| Seem interested in learning more about your relative by talking with you | |||||

| Hardly ever | 30 | 35.3 | 16 | 21.3 | |

| Some of the time | 28 | 32.9 | 38 | 50.7 | |

| Most of the time | 27 | 31.8 | 21 | 28.0 | |

| Have all the information they need to care for your relative properly | |||||

| Hardly ever | 17 | 20 | 9 | 12.2 | |

| Some of the time | 38 | 44.7 | 28 | 37.8 | |

| Most of the time | 30 | 35.3 | 37 | 50.0 | |

| Respond to your questions promptly. | |||||

| Hardly ever | 24 | 28.6 | 11 | 14.7 | |

| Some of the time | 31 | 36.9 | 26 | 34.7 | |

| Most of the time | 29 | 34.5 | 38 | 50.7 | |

| Staff support | |||||

| How often do direct care workers (e.g., nursing assistants) in your relative’s facility: | |||||

| Encourages you to talk about your fears and concerns | |||||

| Hardly ever | 32 | 37.6 | 41 | 55.4 | |

| Some of the time | 19 | 22.4 | 17 | 23.0 | |

| Most of the time | 34 | 40.0 | 16 | 21.6 | |

| Keep you informed about changes in your relative’s condition | |||||

| Hardly ever | 25 | 29.4 | 21 | 28 | |

| Some of the time | 28 | 32.9 | 14 | 18.7 | |

| Most of the time | 32 | 37.6 | 40 | 53.3 | |

| Positive and negative interactions | |||||

| Facility staff were capable of reassuring you when you were upset | |||||

| No | 36 | 43.4 | 20 | 26.7 | |

| Yes | 47 | 56.6 | 55 | 73.3 | |

| Facility staff showed respect to you and/or other family members | |||||

| No | 8 | 9.4 | 6 | 8.2 | |

| Yes | 77 | 90.6 | 67 | 91.8 | |

| Family involvement interview | |||||

| Do you typically perform any of the following activities when you visit your relative? | |||||

| Monitored the quality of your relative’s care at the facility | |||||

| No | 1 | 1.2 | 2 | 2.7 | |

| Yes | 84 | 98.8 | 73 | 97.3 | |

| Monitored staff interactions with your relative | |||||

| No | 5 | 6.0 | 4 | 5.3 | |

| Yes | 79 | 94.0 | 71 | 94.7 | |

| Attended care conferences at the facility | |||||

| No | 31 | 36.9 | 26 | 34.7 | |

| Yes | 53 | 63.1 | 49 | 65.3 | |

| Given suggestions to staff on ways to care for your relative | |||||

| No | 10 | 11.8 | 10 | 13.3 | |

| Yes | 75 | 88.2 | 65 | 86.7 | |

| Directed staff on ways to care for your relative | |||||

| No | 27 | 31.8 | 25 | 33.3 | |

| Yes | 58 | 68.2 | 50 | 66.7 | |

Note. CR = care recipient; CG = caregiver; RLTC = residential long-term care;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Qualitative analysis.

Counselor case notes for sessions completed prior to the completion of the 4-month survey were organized in NVivo 11. Data were thematically analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six steps of thematic analysis. The guiding research question for this analysis was: What were the primary factors impacting participants’ experiences and perceptions of RLTC facilities and staff? The entirety of case notes were divided among six of the authors (RZ, TLS, RB, HM, JF, and CR) for a first read-through and development of initial codes and tentative themes. We followed a phenomenological approach to explore, describe, and analyze participants’ lived experiences and statements: their perceptions, descriptions, and ways of remembering and making sense of events in their own words. Inductive analysis enabled authors to discover patterns, themes, and categories (Marshall & Rossman, 2016; Patton, 2002). Next, the authors each coded an identical subset of case notes and convened to compare interpretations and points of divergence as well as to clarify and refine the coding framework. With open coding, new categories and themes could be identified. We continued practice coding and iterative discussion until all authors were in agreement and consistently coding text excerpts independently. Each author then coded a portion of the case notes. Themes were reviewed and refined to ensure that research questions were adequately addressed. The six authors listed above met weekly to debrief and clarify points of divergence, and audit trails enhanced transparency and credibility of the analysis (Marshall & Rossman, 2016).

Results

Quantitative

Caregivers enrolled in the RCTM treatment group were on average 63 years old. They were nearly all white (98%), mostly female (80%), and nearly 30% were the spouse of their care recipient with the remainder largely consisting of adult children. Care recipients were on average 84 years old, largely white (93%), and two-thirds (66%) female. They lived in a variety of RLTC settings including nursing homes (20%), standard assisted living (21%), and assisted living memory care units (54%). Care recipients had lived in a RLTC community for 17.3 months on average. Caregivers reported visiting 13 times per month for nearly 2.5 hours per visit, on average (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics.

| Characteristics (N = 85) | Caregiver | Care recipient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, M ± SD | 62.6 ± 10.6 | 83.9 ± 8.5 | ||

| Female, N (%) | 70 | (82.4) | 56 | (65.9) |

| White, N (%) | 83 | (97.6) | 79 | (92.9) |

| Married, N (%) | 64 | (75.3) | 32 | (37.6) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher, N (%) | 68 | (80.0) | 33 | (38.8) |

| Household income 40k or greater, N (%) | 68 | (80.0) | 29 | (34.1) |

| Employed, N (%) | 41 | (48.2) | ||

| Spouse of CR, N (%) | 25 | (29.4) | ||

| Residence, N (%) | ||||

| With CG | 1 | (1.2) | ||

| In a nursing home | 17 | (20.0) | ||

| Assisted living-standard | 18 | (21.2) | ||

| Assisted living-memory care unit | 46 | (54.1) | ||

| Family care home/adult foster care | 2 | (2.4) | ||

| Other | 1 | (1.2) | ||

| Medicaid, N (%) | 25 | (29.4) | ||

| Facility stay, months, M (IQR) | 13.4 ± 9.1 | 17.3 | (4.5, 26.5) | |

| Visit frequency, per month, M ± SD | ||||

| Visit length, minutes, M (IQR) | 143.1 | (60, 135) | ||

Note. CR = care recipient; CG = caregiver; IQR = inner quartile range.

After comparing the demographic characteristics of caregivers and care recipients reporting high and low adjustment at baseline, we found that overall, those with high and low adjustment were similar. However, we found that female caregivers reported higher adjustment more frequently than male caregivers (Χ2 (1) = 4.54, p = .033). Additionally, caregivers with a bachelor’s degree or higher reported higher adjustment more frequently (Χ2 (1) = 7.23, p = .007). There was no difference in caregiver adjustment by caregiver employment or relationship to the care recipient (p > .05). Care recipient adjustment to RLTC was not associated with care recipient gender or education nor caregiver or care recipient marital status or household income (p > .05). Caregiver and care recipient adjustment were moderately correlated (r (80) = .311, p = .005).

Between baseline and 4 months, we observed modest, statistically significant increases in mean perceptions of staff communication and the number of positive interactions with staff (F (1, 74) = 7.1, p = .009; F (1, 74) = 6.0, p = .016 respectively). Caregivers also reported more negative interactions with staff during this time (F (1, 73) = 4.1, p = .045). There was no change in perceptions of staff support (F (1, 74) = .3, p = .567). We found that as part of their perceptions of staff communication, caregivers reported diverse experiences at baseline with approximately equal numbers reporting staff “hardly ever,” “some of the time,” and “most of the time” to the questions: “Seemed interested in learning more about [their] relative” and “Respond to [their] questions promptly.” A similar pattern was observed for component questions within the staff support measure. Over 90% of caregivers reported that staff were respectful of them and other family caregivers at baseline. We observed no changes in the adjustment of caregivers or care recipients to RLTC (F (1, 66) = .1, p = .766; F (1, 74) = .6, p = .439 respectively) (Table 2).

Qualitative

Case notes provided rich insights into factors influencing caregivers’ experiences with communities and community staff and offered context to the quantitative results. Themes of (1) communication, (2) care, (3) relationships with staff, (4) community systems, (5) finances, and (6) location were identified as the primary factors impacting caregivers’ experiences. Below we describe each theme in depth. Participant names are pseudonyms.

Communication.

Qualitative results emphasized that productive communication among community staff, the caregiver, and other providers (e.g., hospice and occupational therapy) was an important component of caregivers’ positive experiences. Consistent communication from community staff about major changes and routine updates in their relative’s care was considered essential to building trust, although inconsistent or frantic phone calls from staff with incomplete information were sources of stress for many caregivers. Timely communication about community changes, such as construction, flu outbreaks, or administrative shifts was also important. A lack of communication caused caregivers to express dissatisfaction and stress. The TC worked with caregivers to identify their preferred mode of communication (e.g., email, phone, and in-person) and communicate their preferences to community staff.

Not knowing which staff member to contact for issues and concerns was a frustration for many caregivers. One caregiver suggested communities have a single point of contact for families or a staff directory that clearly listed who to contact for different concerns. Many caregivers felt comforted by having a staff member they trusted and had established a bond with as a point of contact. Martha (daughter, 62 years old) explained the relationship she and her brother had with staff caring for their mother,

There’s one young woman on the day shift that is super connected to my brother, and she’s really great. When I call I try to talk to her, she’ll tell me what’s going on, and she’ll let me know anything she’s concerned about.

The TC worked with caregivers to identify specific staff who they felt comfortable communicating with at the RLTC. The TC also encouraged caregivers to advocate for the RLTC to share a staff directory to help families know who to contact for specific needs and questions.

Lack of communication between staff members, or between staff and external service providers, was a common frustration. When asked about recent communication issues with the community, Sue (daughter, 65 years old) answered,

Just the usual stuff. The usual: they lost her paperwork and this or that. That just is constant, no matter where you go. The right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is doing sometimes.

Communication about the care recipient’s personal history, family, personality, and preferences was important to establishing person-centered care (Fazio et al., 2018). It was critical to many caregivers that the staff know the personality and personal history of their care recipient before the onset of dementia. Whether this information was solicited and utilized by communities varied greatly. Case notes for Tessa (daughter, 59 years old) highlight the importance of staff taking personal interest in residents:

[Tessa’s] mother is very happy with the staff at the home. She related that they are a tight group and have been working together for years. They are very kind to the residents and seem to really like her mother. She noted that they take a personal interest in each resident and go out of their way to make them comfortable and engaged. She noted that they personalize her care. They take the time to find out about her mom and her mom’s life story. They inform her of what is happening with her mom when she visits. They call her with information and are never “panicked.”

As part of the RCTM intervention, the TC strongly encouraged caregivers to share their relative’s preferences and life experiences with community staff. For example, several caregivers made shadow boxes or scrapbooks with pictures and mementos from their care recipient’s life to display in the room as a reminder for staff and visitors of their relative’s interests and life history.

Care conferences were another important mode of communication that helped to establish clear lines of communication between staff and families. Care conferences were offered by RLTC facilities and utilized by caregivers to varying degrees. Some caregivers were un-aware of the concept of care conferences, while others were frustrated by the lack of care conferences, did not know how to request them, had their requests poorly received by the community, or poorly attended by key staff. In these instances, the TC coached caregivers on who and how to ask for a care conference as well as which issues to raise or requests to make.

Care.

The quality and appropriateness of care provided by the community to care recipients was another important factor influencing caregiver experiences. Concerns over safety, falls, wandering, abuse, and neglect were frequent causes of dissatisfaction with the community. Carmen (daughter, 62 years old) stated:

I don’t know how hard to fight the facility. Some of the things I’m just so livid with. When her clothes are drenched and she’s on her wheelchair seat that reeks of urine… I’m afraid that [a letter to the administrator] is going to fail, so I don’t send it. Or I’m afraid things will get worse, that they’re angry that I spoke up.

Activity of daily living-related care challenges such as bathing, toileting, and dressing were commonly mentioned. Sandra (daughter, 55 years old) elaborated on her frustration regarding inadequate bathing and dressing care for her mother:

Now she needs to be prompted to shower, she didn’t used to be. Every time I’d call and complain they would turn it around on my mom and say that she refused the service. They’d say that [mom has] the right to refuse service. But that’s just an excuse. I think it’s an excuse for them to not do what they’re supposed to do…ENOUGH! She deserves to be treated better. When I went to visit mom on Saturday she was walking around in capris and a tank top [in the winter]. She didn’t have a brief on. They hadn’t toileted her. I still haven’t called the Ombudsman, I wasn’t sure if it’s abuse but it’s definitely neglect.

Several caregivers were unsure if their safety concerns rose to the level of abuse and whether or not to report it to authorities. In these instances, the TC discussed the situation with the caregiver and provided information on the local RLTC Ombudsman and encouraged communication with the community as appropriate.

When caregivers and staff acted collaboratively to brainstorm solutions, caregivers tended to feel better about the situation. For example, Carol’s (wife, 73 years old) husband disliked being bathed because “he feels like he’s kind of being “manhandled”.” After talking with the TC about how vulnerable and disorienting bathing can be for someone living with dementia and brainstorming ideas to address this, Carol suggested to staff that just one person do the shower instead of three “ganging up” on him. Following her suggestion, Carol shared that her husband was showering without any issues.

Medication management was another common point of contention between staff and families. Often this was in relation to staff not letting families know when medication was being changed or failing to include them in the decision-making process. Several caregivers felt that their care recipient was being inappropriately medicated in an effort to deal with difficult behavior when nonpharmacological techniques to manage behavioral issues could be used instead. Dorothy (daughter, 67 years old) expressed her frustration with the management of her mother’s medication:

They called and said they were going to put mom back on medications. I heard that through the hospice, not from the [the community], though they were the ones who decided. I’m not happy about that. She’s back on one dose of Depakote and Ativan as needed. I need to find a time to talk to them. I want to be notified of changes. I am her healthcare agent; I should be informed right up front. A few weeks later Dorothy reported: “Changing medications yet again, to Zyprexa, which I am not happy about. Last week the nurse gave mom Dilaudid because she couldn’t handle mom’s behavior. That is not okay.” When asked if Dilaudid was on her mom’s list of approved medications, Dorothy said that it was not. As concerns about medication use were commonly raised by caregivers, the TC frequently talked through specific medications, provided information, and encouraged caregivers to talk with the care recipient’s primary care provider to decide which medications were appropriate.

Caregivers often mentioned staff competency and level of training in dementia care, as expressed by Beth (daughter, 59 years old) regarding an interaction with the director of nursing:

Somebody who should be trained in this area and act like… like my mom is a “bad child” and they are frustrated. As if living with it on our part is an easy task. I’d like to let them know that they’re professionals and are supposed to be handling it. This is dementia care! We all have our bad days, but I don’t think they need to make apparent to us that she’s difficult to deal with.

For many caregivers it was unclear how much or if any dementia-specific training had been provided to staff, despite the setting being labeled a “memory care” community. The TC provided information on best practices for dementia care and encouraged caregivers to make use of this information during care conferences or when care needs to be changed.

Relationships with staff.

Interpersonal relationships between care recipients and community staff as well as between caregivers and community staff were integral to caregivers’ experiences with the RLTC community. Many caregivers had good rapport with staff and praised them for their warmth and compassion toward residents. Caregivers mentioned the importance of staff calling residents by name and treating them with respect. Carol expressed her relief knowing that staff had a good relationship with her husband:

They are very good to him. One of the things that I like is they always call him by name, and me as well. They treat him like a person. That’s the greatest fear—that you’ve warehoused your loved one…to a place like you see in the movies, or sometimes what you see in reality.

Others, such as Dorothy, expressed negative relationships between her mother and staff:

“There is no sense of warmth or care. I feel like they don’t like my mother but they do like her money.” Caregivers were attuned to the attitudes of staff. Several lamented that staff did not take pride in their work and that their care recipient received poor care as a result, such as Meg (daughter, 76 years old):

So my mother’s care was almost 100% sitting in front of the TV. They made a little bit of an effort to get her to an exercise class. I pleaded with them to give her attention and to eat at least one meal in the dining room. The aides were extremely sully and very.. sort of.. lackadaisical. It seemed like they didn’t want to do what they were doing.

Positive staff attitudes were considered an enormously beneficial attribute of the community. Nancy, who was caring for her husband John and his twin brother Jeffrey, expressed her satisfaction with the staff at their community:

[The community staff member] said that John and Jeffrey think they are in their college dorm. So [the staff member has] been printing off quizzes and they’ve loved it. I praised her for that, that she took the initiative to do that…The other thing I saw when I was there, we were sitting in the dining room shortly after dinner… I looked over at a table on the other side of the room. One of the residents said “I want to dance!” And the aide went and got an iPad and played music. It was just lovely. That has to give the staff a sense of satisfaction.

Caregivers had more confidence in the care of their relatives when staff treated care recipients with respect and dignity, acted amiably, and took initiative. The TC validated caregiver concerns, worked with caregivers to look for instances where staff were being positive, and encouraged caregivers to be role models in how to treat residents well.

An important aspect of the community–caregiver relationship was staff responsiveness to caregiver suggestions. Caregivers felt supported when they had agency in their care recipient’s care and staff employed a collaborative approach. Gail (daughter, 72 years old) explained how she was working with staff to get her father to bathe:

We’re trying to work together, the staff and me. I really try to work hard with them, we’re working as a team pretty much. That’s what we have to do… I feel like I’m a part of the community there. I think we’re a team and we work together as a team.

Caregivers felt supported when they knew the concerns they raised to staff would be addressed. Conversely, in some facilities caregiver concerns or suggestions went unheeded. Case notes from Jerry’s (husband, 89 years old) experience illustrate how his concerns were ignored:

When Jerry was visiting, he noticed that Betty was “antsy.” He figured out that she needed to use the restroom and told staff. The staff member told him, “She goes to the bathroom all the time” as if to avoid taking her. His wife ended up walking away and Jerry thought she was going to her restroom. Instead she went to another room and defecated on the floor. Jerry was upset that he made the staff aware that his wife needed to use the restroom, but since they didn’t respond, she “made a mess” on someone’s floor.

Some caregivers felt comfortable making suggestions and raising concerns to staff while others had difficulty being assertive. A few caregivers expressed being unsure if their expectations were realistic or if community and staff actions were normal. In these instances, the TC provided validation of the caregiver’s concerns and helped them brainstorm solutions. For caregivers with specific upcoming one-on-one conversations with staff or care conferences, the TC coached caregivers by providing suggestions and structure to address concerns in the conversation.

Facility system.

Infrastructural elements such as the physical environment, available levels of care, activities provided, and staffing also influenced caregivers’ experiences. The availability and condition of the sociophysical environment, including indoor and outdoor facilities, were noted by caregivers. Enjoyable outdoor spaces such as courtyards, gardens, and walking paths, and bright and clean inviting indoor environments were assets, while a lack of interior private spaces to socialize was a barrier. Sue (daughter, 65 years old) mentioned a need for private areas to visit with her mother:

I can’t stay in her room because it is so cluttered up with stuff. We walk down to the gazebo, but that is the only space where you can go. There really is no other place to go see your person in the facility. They need some more nooks and crannies for people to go and visit.

Patty (daughter, 65 years old) also lamented the lack of communal places to socialize:

The building itself I wish had more common spaces. But there’s her room where she sleeps and the dining room, basically. The dining room is the only place to sit and socialize. No living room cubbies or atriums. It’s an older place.

To provide assistance in dealing with space issues, the TC explored with caregivers how to adjust to building layout limitations and problem-solved together how to best use the space available. For instance, the TC would suggest going outside for visits or coordinating visits around activities and meal times so there was more privacy in shared spaces.

Levels of care available at the community were frequently mentioned as a concern. Some communities included multiple levels of care and caregivers expressed relief knowing that should their care recipient need more care in the future they would not have to move communities. Others faced the possibility of or even experienced an abrupt transition to a different community, as recorded in case notes for Tessa:

[The community] told Tessa that her mother had become “a wandering risk” and needed to move out within 30 days. Tessa expressed her dissatisfaction with the facility’s manner of handling the situation. She was upset by the immediate need to hold a meeting under the pretense of a plan for care when they were actually going to “kick her out” of her housing.

Transitions, whether to a new community or a new room in the same community, were almost always a source of stress for both the caregiver and care recipient. When these issues were raised, the TC coached the caregiver through the transition and provided suggestions on how to more smoothly move a person with dementia into another room or community.

Another important aspect of the community was the activities offered to residents. Several caregivers were not happy with the amount of activities offered at the community and felt their care recipient was left to “twiddle their thumbs” all day. This was especially a problem for men, as many of the activities offered were perceived as oriented to women. The TC coached caregivers on how to advocate for increased and/or appropriate activities for residents. Other caregivers were happy with the quantity and variety of activities and felt their care recipient was sufficiently entertained and engaged with activities such as movie nights, painting parties, art therapy, music, yoga, happy hour, and religious activities.

Staff turnover and personnel shortages were very common concerns among caregivers. Abigail (daughter, 64 years old) stated:

Everytime I go there, someone has left. Now the ones remaining work 14-16 hour days. If mom wasn’t on hospice, I’d be very concerned about her care; they are stretched so thin…It’s unnerving to me that they’re always short of staff. I don’t think that’s uncommon. Last Sunday when I was there, they were arguing with one another about who needs to take care of what.

Caregivers found it challenging to build trusting relationships when staff were coming and going so frequently. This led to a sense of overall tumult in the system and stress for caregivers.

Numerous caregivers mentioned understaffing, particularly on weekends. The TC worked with many caregivers to set realistic expectations for themselves as well as staff and the RLTC system in general in regard to staffing issues. Most caregivers acknowledged that staffing was an industry-wide issue and recognized that staff are underpaid, overworked, and doing the best they can with the given limited resources.

Finances.

Payer source, such as long-term care insurance or Medicaid, and available finances often limited community and care options which in turn influenced caregivers’ experiences with the RLTC community. Case notes from Naomi (daughter, 54 years old) illustrate this:

Naomi’s parents have long term care insurance. Naomi noted that it was frustrating to find a place you like and then realize long term insurance won’t cover that specific place. [The community] has raised the rates three times in the past 11 months. Long-term care insurance does not pay unless they have an Alzhiemer’s license. She can’t find a facility near her that has an Alzhiemer’s license.

Some caregivers strategically “spent down” assets in advance in order to qualify for Medicaid. After her mother’s savings were depleted, Naomi’s mother went on Medicaid. However, Naomi was unsure if the current community accepted Medicaid or if her mother would be moved to a shared room as a result of the change in payer source. This uncertainty was commonly raised by caregivers. As such, the TC often encouraged caregivers to promptly, or when possible, preemptively discuss potential consequences of changes in payer source with the RLTC administration.

In addition, the TC regularly discussed finances with caregivers and provided coaching around difficult conversations with community billing staff, as well as guidance when pursuing Medicaid or Veterans’ benefits. The sheer cost of paying for the RLTC was a concern for nearly all caregivers and many, such as Claire (daughter, 64 years old), expressed fear of running out of money: “The one big concern I have about my mom is whether she will outlive the money I have for her. I really would like to keep her in this nice facility.” A few families depleted their funds and had to move their care recipient to a new community. Often these moves were abrupt and traumatic for the care recipient when adjusting to a new home. For caregivers who had financial resources to pay privately for the duration of their care recipient’s stay, such arrangements were often expressed with great relief. However, paying for the care recipient’s stay often conflicted with other emotions, such as knowing that their parent would not want money to be spent on RLTC but rather go to an inheritance.

The perceived value of the community was mentioned by several caregivers. Some expressed frustration, feeling that they were not getting what they paid for or that the community was trying to “nickel and dime” them. Jackie (daughter, 52 years old) was displeased with the billing at her mother’s community:

This is your mother, she should have the best of everything, but yet when you’re in this situation and you want to make the money last. Then you question, especially when they have the a la carte method, it’s just kind of yucky and off putting.

Complaints of unexpected charges, frequent rate increases, excessive paperwork, and billing confusion were often attributed to the community, while concerns over financing were seen as outside the community’s control.

Location.

Location was often a limiting factor for caregivers in selecting a community, especially in rural areas. It was important to many caregivers that the community be in close proximity so that they could conveniently visit and monitor their care recipient’s care. In some cases, caregivers were willing to compromise other important community characteristics such as cost and quality of care in order to be nearby.

Other caregivers like Tina (daughter, 68 years old) had to manage living far from the RLTC. “It’s hard for us because she’s so far away. If she was close we could do more frequent, short visits.” Proximity (or lack thereof) was the source of many emotions for caregivers: guilt about not visiting frequently enough, stress/burden over frequent visits, frustration over long-distance caregiving and coordinating caregiving responsibilities with other family members. The TC frequently coached caregivers on their availability to visit their care recipient, setting reasonable personal expectations, and how to build relationships with community staff from afar (via email or phone calls) or during brief visits when the caregiver was in town. Long-distance caregivers expressed a lack of control and found forming relationships with community staff to be particularly challenging given their lack of regular face-to-face time and opportunity to build rapport.

Discussion

In this mixed methods analysis of family caregiver experiences following the transition of a relative to a RLTC setting, we examined themes associated with communities and staff relationships as well as RLTC stressors and secondary role strains. We also examined potential targets for future interventions. We found that over 4 months of telephone or video counseling with a TC, perceptions of staff communication and positive interactions with staff improved modestly and significantly while perceptions of staff support did not. As part of their assessment of staff communication, caregivers reported higher scores for care-related information and responding to questions but did not report an improvement in community staff interest in learning more about the care recipient. Qualitative results illustrate the importance of timely, accurate information for building trust between caregivers and community staff. This topic was frequently discussed and the TCs supported caregivers in their efforts to improve communication by identifying a point of contact among the staff and their preferred means of communication. These findings are consistent with researchers’ work identifying reciprocity and open communication as essential elements of relationship building between caregivers and staff (Law et al., 2017).

Caregivers reported consistently high levels of perceived respect from community staff. Within the qualitative results, we found building respect could be as simple as staff learning the names of caregivers. For many caregivers, perceptions of staff communication and positive interactions may be improved by a single experience such as a care conference or discussion with a supervisor. In contrast, perceptions of staff support, which includes items related to discussing fears and concerns, may take longer to improve. Studies have shown that feeling reassurance and emotional support from staff are important to overall family satisfaction with community care (Law et al., 2017). Components of the staff support measure reflect caregiver trust of community staff. We saw that trust could be slow to develop and negatively impacted by a single interaction such as a frantic or confusing phone call.

Case notes highlighted both the importance and difficulty of improving communication between family caregivers and community staff. Results from the Family Involvement Interview indicated that caregiver involvement supervising and directing care remained consistent during the intervention. Care conferences were highly attended by families before and after the intervention when offered. Unfortunately, they were often underutilized by communities and some family caregivers found them unsatisfying.

Caregivers also indicated that high staff turnover made communication difficult and impeded their ability to develop a relationship with community staff. Some caregivers reported lack of proximity to the community also interfered with relationship building. Interestingly, Dillman et al. (2013) found that although distance decreases contact, contact alone does not improve family perceptions of the RLTC or care provided. A more home-like environment, positive resident–staff interactions, and responsive care influenced family perceptions. These examples illustrate that although the caregivers were eager to engage with staff and the TC could guide caregivers through requesting and attending care conferences or provide advice on relationship building, these efforts could be hindered by community culture (e.g., friendliness of interactions), location, resources, and/or management practices.

Facility features like location, finances, and building layout also impacted caregivers’ perception of quality of life and care provision. Kemp et al. (2013) emphasized the importance of situational characteristics that are external to the resident and caregivers in constructing a resident’s convoy of care. Inordinate costs, caregiver distance to RLTC, and lack of space to meet privately were commonly noted as playing an appreciable role in caregiver satisfaction and involvement and resident quality of life.

Ultimately, the lack of meaningful changes during counseling may have a number of contributing factors. Follow-up longer than 4 months may be necessary to measure changes in caregiver perceptions of staff communication, interactions, and support. Many caregivers in the study remained engaged with their TC after completing the six formal counseling sessions and 4-month survey. As care setting and context were unique for each care recipient, the quantitative measures may not have captured the most salient elements of caregivers’ experiences with communities and staff. Furthermore, quantitative measures may be insufficient to fully evaluate the effects of a complex psychosocial intervention such as the RCTM. As such, the mixed methods approach enabled caregivers to describe in their own words their concerns about communities and staff and perceived benefits of the intervention. Although quantitative findings were limited in scope and explanation, qualitative analysis of counseling sessions demonstrate that the RCTM provided real-time opportunities for caregivers to raise concerns about communities and staff and receive coaching, suggestions, and plans to improve communication and their experience with the community.

Clinical Implications

Though this was a preliminary study, case notes from the RCTM counseling sessions provide insight into how clinicians can better support caregivers following the transition of their care recipient to a RLTC community. It is important that clinicians meet caregivers where they are and adapt content to meet individual caregiver needs and knowledge level. For most caregivers, this was their first experience caring for someone in RLTC and they had little to no baseline understanding of appropriate expectations for communities and staff. As needed, clinicians can help caregivers adjust their expectations and offer relevant resource referrals (e.g., local ombudsman, support groups, and Medicaid information). It may also be helpful for clinicians to talk caregivers through specific situations, role play conversations with family members and/or community staff, and coach caregivers in conflict management and stress reduction techniques. In our study, many issues experienced by caregivers were time sensitive. It is important that clinicians are available to offer support as issues arise. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, clinicians can provide support by showing empathy and validating caregivers’ feelings, experiences, and decisions. Many caregivers in our study felt isolated, believing their feelings and experiences to be abnormal. Clinicians can let caregivers know they are not alone and that many caregivers share similar feelings and experiences.

Recommendations for Residential Long-Term Care Communities

The preliminary qualitative and quantitative findings help to shed light on potential clinical targets for psychoeducational and psychosocial interventions that could assist dementia caregivers in navigating the RLTC transition. The findings indicate that future interventions may benefit from working directly with communities, including providing them specific recommendations for easing the transition to RLTC for families and residents. Although some issues caregivers identified such as staff shortages and financing concerns are systemic and not easily modifiable, the findings point to a number of practical changes that communities and staff can make to better support caregivers. Facilities can strive to maintain clear lines of communication with family caregivers, especially those who are caregiving from a distance. Communication may take the form of regular newsletters or email updates, phone calls for more specific or urgent updates, and care conferences. Care conferences appear to be most beneficial when they are scheduled at regular intervals by RLTC leadership (rather than relying on families to coordinate) and are attended by key RLTC personnel. Facilities can also encourage staff to get to know the personal history of residents (e.g., by creating scrapbooks, shadow boxes, or mementos placed in rooms). Furthermore, communities can encourage staff to greet residents and their family caregivers, call them by name, and introduce themselves. Staff can ask caregivers to share suggestions and concerns, and when expressed, help address them in a timely manner. Staff can also include caregivers in medication management decisions.

Future interventions may also seek to educate facilities on the importance of creating inviting indoor and outdoor places for visitors to spend time with residents, to the extent possible. Facilities can review the activities they offer to ensure variety and that they meet resident needs. Communities can also help ease caregivers’ stress by providing clear, open, and consistent information regarding finances and billing. For example, communities can explain rate increases in advance and be available to answer billing questions as they arise.

COVID-19 Implications

Since caregivers have faced significant visiting restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, they have not been able to communicate as easily with the staff. Casual conversations often provided a spontaneous opportunity to receive updates on how residents were doing and allowed time for questions. Given the noted importance of communication between caregivers and staff, it will be very important for staff and caregivers to make the effort to engage in regular communication with each other to discuss updates, questions, and concerns. These conversations will also help maintain caregiver–staff relationships and ease caregiver feelings of being disconnected from their family member.

Staff should also work to increase the RLTC activity offerings. Residents would likely benefit from increased activity as they do not have the activity of their regular visits. In addition, one-on-one attention from staff would be a helpful substitute for the loss of attention residents typically receive from family visits.

Limitations

Results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, this was a preliminary analysis examining a subset of participants through their first 4 months in the intervention. Although the analysis did not include data from the full participation period of 12 months due to available sample size, the qualitative analysis reached saturation. The sample is largely white and middle class so the results may not generalize to a more diverse population. Future research should seek to include populations with greater racial/ethnic and socioeconomic diversity. The study included both family caregivers who had recently transitioned their care recipient to RLTC and those whose transition was not as recent (on average, care recipients had lived in the community 17.8 months with the midspread ranging from 4.5 to 26.5 months). Based on anecdotal reports from study participants, we anticipate the RCTM intervention has the greatest impact for those who have more recently transitioned their care recipient. Future research should focus on the period of time immediately before and directly following the care recipient’s transition to RLTC.

Finally, care recipients in the study resided in nursing homes, assisted living communities, and other care homes. These settings differ in level of care, supervision, and activities provided. For example, in assisted living communities, family members tend to play a key role in monitoring care recipient health, social life, and finances (Port et al., 2005; Zimmerman et al., 2020). Compared to nursing homes, assisted living communities employ fewer medical professionals and have less stringent training requirements for care staff (Zimmerman et al., 2020). The RCTM intervention was tailored to the individual needs of each caregiver regardless of setting. However, it is likely that many commonly reported caregiver experiences were the result of the systemic influences of care setting (e.g., navigating the private pay requirement of most assisted living communities). Future research should limit or stratify by care setting to tease out these system impacts.

This study demonstrates the importance and complexity of fostering relationships between family caregivers and RLTC community staff as we prepare for a growing number of care recipients entering RLTC. Our findings show that focusing on family caregiver and staff communication and relationship building as well as regular discussion of care, finances, and the community are crucial to the mental and emotional health of caregivers of persons with dementia residing in RLTC. These topic areas should be core clinical targets for current and future interventions designed to assist families in adapting to the RLTC transition. Family caregivers are a diverse group with equally diverse opinions and perceptions of care; therefore, initiating targeted conversations between caregivers and staff early and often in the transition to residential care will support strong working relationships between these two groups and promote successful adjustment for caregivers and care recipients.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant No. 5R18HS022836).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2020). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement, 16, 391–460. [Google Scholar]

- Barken R, & Lowndes R (2018). Supporting family involvement in long-term residential care: Promising practices for relational care. Qualitative Health Research, 28(1), 60–72. doi: 10.1177/1049732317730568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, Fetherstonhaugh D, Tarzia L, & Chenco C (2014). Staff-family relationships in residential aged care facilities: The views of residents’ family members and care staff. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 33(5), 564–585. doi: 10.1177/0733464812468503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, & Nay R (2011). Improving family-staff relationships in assisted living facilities: The views of family. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(6), 1232–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05575.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramble M, Moyle W, & McAllister M (2009). Seeking connection: Family care experiences following long-term dementia care placement. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(22), 3118–3125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02878.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks D, Fielding E, Beattie E, Edwards H, & Hines S (2018). Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on the psychological health and emotional well-being of family carers of people with dementia following residential care placement: A systematic review. JBI Database ofSystematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 16(5), 1240–1268. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CK, Sabir M, Zimmerman S, Suitor J, & Pillemer K (2007). The importance of family relationships with nursing facility staff for family caregiver burden and depression. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 62(5), P253–P260. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.5.P253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman JL, Yeatts DE, & Cready CM (2013). Geographic distance, contact and family perceptions of quality nursing home care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(11–12), 1779–1782. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery JE, Yu F, Davila HW, & Shippee T (2014). Alzheimer’s disease and nursing homes. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 33(4), 650–657. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio S, Pace D, Maslow K, Zimmerman S, & Kallmyer B (2018). Alzheimer’s association dementia care practice recommendations. The Gerontologist, 58(Suppl. 1), S1–S9. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garity J (2006). Caring for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease: Coping with caregiver burden post-nursing home placement. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 32, 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Anderson KA, Zarit SH, & Pearlin LI (2004). Family involvement in nursing homes: Effects on stress and well-being. Aging & Mental Health, 8(1), 65–75. doi: 10.1080/13607860310001613356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, & Kane RL (2007). Families and assisted living. The Gerontologist. 47(3), 83–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Reese M, & Sauld J (2015). A pilot evaluation of psychosocial support for family caregivers of relatives with dementia in long-term care: The residential care transition module. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 8(4), 161–172. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20150304-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Statz TL, Birkeland RW, Louwagie KW, Peterson CM, Zmora R, Emery A, McCarron HR, Hepburn K, Whitlatch CJ, Mittelman MS, & Roth DL (2020). The residentialcare transition module: A single-blinded randomized controlled evaluation of a telehealth support intervention for family caregivers of persons with dementia living in residential long-term care. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 133.doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01542-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone J, & Wexler E (2002). Exploring the relationships between families and staff caring for residents in long-term care facilities: Family members’ perspectives. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 21(1), 39–46. doi: 10.1017/S0714980800000623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haesler E, Bauer M, & Nay R (2007). Staff–family relationships in the care of older people: A report on a systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health, 30(4), 385–398. doi: 10.1002/nur.20200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R, Caffrey C, Rome V, & Lendon J (2016). Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the national study of long-term care providers, 2013-2014. Vital & Health Statistics. Series 3, Analytical and Epidemiological Studies, 38, 1–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg A, & Ekman SL (2000). ‘We, not them and us?’ Views on the relationships and interactions between staff and relatives of older people permanently living in nursing homes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(3), 614–622. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J, Gomersall JS, Campbell J, & Hughes M (2015). Carers’ experiences when the person for whom they have been caring enters a residential aged care facility permanently: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 13(7), 241–317. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL (2012). Married couples in assisted living: Adult children’s experiences providing support. Journal of Family Issues, 33(5), 639–661. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11416447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, & Perkins MM (2013). Convoys of care: Theorizing intersections of formal and informal care. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(1), 15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely DK, Simon SE, Jones RN, & Morris JN (2000). The protective effect of social engagement on mortality in long-term care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(11), 1367–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law K, Patterson TG, & Muers J (2017). Staff factors contributing to family satisfaction with long-term dementia care: A systematic review of the literature. Clinical Gerontologist, 40(5), 326–351. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2016.1260082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore M, Ferrell A, & Wiener JM (2017). Living arrangements of people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Implications for services and supports (p. 23). [Issue brief]. Retrieved from research summit on dementia care: building evidence for services and supports website: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/257966/LivingArran.pdf

- Maas M, Reed D, Park M, Specht JP, Schutte D, Kelley LS, Swanson EA, Trip-Reimer T, & Buckwalte KC 2004). Outcomes of family involvement in care intervention for caregivers of individuals with dementia. Nursing Research, 53(2), 76–86. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200403000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C, & Rossman G (2016). Designing qualitative research (6th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, & Skaff MM (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod JD, Kane RA, & Kane RL (2000). Effects of posthospital informal care on nursing home discharge. Research on Aging, 22(1), 66–82. doi: 10.1177/0164027500221004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Hegeman CR, Albright B, Henderson C, & Morrow-Howell N (1998). Building bridges between families and nursing home staff: The partners in caregiving program. The Gerontologist, 38(4), 499–503. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.4.499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port CL, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Dobbs D, Preisser JS, & Williams SW (2005). Families filling the gap: Comparing family involvement for assisted living and nursing home residents with dementia. The Gerontologist, 45 Spec No 1(1), 87–95. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AR, & Ishler KJ (2018). Family involvement in the nursing home and perceived resident quality of life. The Gerontologist, 58(6), 1033–1043. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison J, Curry L, Gruman C, Porter M, Henderson CR, & Pillemer K (2007). Partners in caregiving in a special care environment: cooperative communication between staff and families on dementia units. The Gerontologist, 47(4), 504–515. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.4.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AA, & McKenna H (2015). ‘It’s the little things that count’. Families’ experience of roles, relationships and quality of care in rural nursing homes. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 10(1), 38–47. doi: 10.1111/opn.12052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sury L, Burns K, & Brodaty H (2013). Moving in: Adjustment of people living with dementia going into a nursing home and their families. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(6), 867–876. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utley-Smith Q, Colón-Emeric CS, Lekan-Rutledge D, Ammarell N, Bailey D, Corazzini K, Piven ML, & Anderson RA (2009). The nature of staff - family interactions in nursing homes: Staff perceptions. Journal of Aging Studies, 23(3), 168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Schur D, Noelker LS, Ejaz FK, & Looman WJ (2001). The stress process of family caregiving in institutional settings. The Gerontologist, 41(4), 462–473. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.4.462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SW, Zimmerman S, & Williams CS (2012). Family caregiver involvement for long-term care residents at the end of life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(5), 595–604. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Cohen LW, Reed D, Gwyther LP, Washington T, Cagle JG, Sloane PD, & Preisser JS (2013). Families matter in long-term care: Results of a group-randomized trial. Seniors Housing & Care Journal, 21(1), 3–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Katz PR, Kunze M, O’Neil K, & Resnick B (2020). The need to include assisted living in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(5), 572–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, & Reed D (2014). Dementia prevalence and care in assisted living. Health affairs (Project Hope), 33(4), 658–666. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]