Abstract

Background:

The incidence of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma (OTSCC) is increasing among younger birth cohorts. The etiology of early onset OTSCC (diagnosed before age 50) and cancer driver genes remain largely unknown.

Methods:

The Sequencing Consortium of Oral Tongue Cancer was established by pooling somatic mutation data (N=227, 107 early onset) from seven studies and The Cancer Genome Atlas. Somatic mutations at microsatellite loci and COSMIC mutation signatures were identified. Cancer driver genes were identified using the MutSigCV and WITER algorithms. Mutation comparisons between early and typical onset OTSCC were evaluated using linear regression with adjustments for patient-related factors.

Results:

Two novel (ATXN1, CDC42EP1) and five previously reported (TP53, CDKN2A, CASP8, NOTCH1, FAT1) driver genes were identified. Six recurrent mutations were identified, four occurring in TP53. Early onset OTSCC had significantly fewer non-silent mutations even after adjustment for tobacco use. No associations were observed between microsatellite loci mutations and mutation signature with age of OTSCC onset.

Conclusions:

This international multicenter consortium is the the largest study to characterize the somatic mutational landscape of OTSCC and the first to suggest differences by age of onset. This study validates multiple previously identified OTSCC driver genes as well as proposes two novel cancer driver genes. In analyses by age, early onset OTSCC had a significantly smaller somatic mutational burden that was not explained by differences in tobacco use.

Keywords: oral tongue cancer, TP53, NOTCH1, tobacco, age of onset

Lay Summary:

We identified seven specific areas in the human genetic code which could be responsible for promoting the development of tongue cancer. Tongue cancer in young patients (under age 50) has fewer overall changes to the genetic code when compared to older patients, but we do not think this was due to differences in smoking rates between the two groups. The cause of increasing cases of tongue cancer in young patients remains unclear.

Precis:

We identified seven putative OTSCC driver genes (TP53, CDKN2A, CASP8, NOTCH1, FAT1, ATXN1, CDC42EP1) and found that early onset OTSCC had a significantly smaller somatic mutational burden that was not explained by differences in tobacco use.

Background

The incidence of most head and neck cancers have been declining with decreasing rates of tobacco consumption in many developed countries1, 2. However, the incidence of two head and neck cancer subtypes, oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) and oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma (OTSCC) are on the rise3-7. For OTSCC, the largest increase in incidence has been observed among young males and females (< 50 years of age at diagnosis)3, 6, 7. While, the rise in OPSCC has been attributed to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection8, no obvious cause for OTSCC has been identified9.

Several molecular studies have investigated whether early onset OTSCC is a distinct molecular subtype of OTSCC, including 7 whole exome sequencing (WES) studies10-16. While none reported significant molecular differences between early and typical onset OTSCC, these studies were likely unpowered to detect differences due to small samples sizes (range: 3 to 23 early onset cases) and had varying definitions of early onset OTSCC. Additionally, only 20 of the OTSCC cases (25%) included in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) are early onset (< 50 years of age at diagnosis), precluding detailed analyses.

To characterize the somatic mutational landscape of early onset OTSCC and elucidate specific cancer driver genes, we established The Sequencing Consortium of Oral Tongue Cancer (SCOTC). This consortium incorporates existing WES data from seven single-institution studies and the TCGA for a total of 227 OTSCC cases. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to investigate the somatic mutational landscape of OTSCC and to identify possible differences by age of onset.

Methods

The Sequencing Consortium of Oral Tongue Cancer (SCOTC)

SCOTC is a consortium of 227 OTSCC cases with existing WES data from seven studies spanning seven institutions and the TCGA. To establish this consortium, a review of Pubmed, Google Scholar, and Embase was conducted to identify peer-reviewed articles using whole genome or exome sequencing to study early onset OTSCC. Search algorithms for each database are detailed in the supplementary materials. Studies were excluded for the following reasons: non-SCC forms of oral tongue cancer, targeted sequencing of specific genes only, non-English articles, and case reports (Supplemental Figure 1). For the eligible studies, authors were contacted and invited to join the SCOTC. If agreeable, authors provided raw sequencing data as well as all available demographic, pathologic, and clinical data.

Description of Included Studies and Study Population

The seven studies10-17 included in SCOTC were performed on a variety of different patient populations using multiple sequencing platforms. Age specific analyses were also performed using varying definitions of early onset OTSCC. The specifics of each study are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. WES data from 80 OTSCC tumor specimens from the TCGA (35.2% of included cases) was also included in this analysis. Patients were excluded from our analyses if the documented tumor site overlapped with other oral cavity (e.g. floor of mouth) or oropharyngeal sites (e.g. base of tongue). Demographic and clinical information were collected from each study. Patient age and gender were available for all patients. Due to the varied classifications across studies, binary (ever vs. never) variables were created for tobacco and alcohol use. Overall tumor stage was also gathered when available.

Somatic Mutation Data Processing and Annotation

In order to pool somatic mutation data from the eight included studies, we converted data identfied from the reference hg18 (studies by Li et al.12 and Boot et al.11) to the reference hg19. Of these studies, Boot et al.11 generated mutations only in tumor tissues. To minimize artifacts and germline events, we applied a stringent germline filtering pipeline, as followed by the Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange (GENIE) project. We removed mutations with the frequency >0.1% in the Asian populations from the 1000 Genomes project or the Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) database. The combing mutation data were annotated with the ANNOVAR tool18. Somatic mutations were classified as silent and non-silent mutations such as missense, frameshift/non-frameshift, splicing, and nonsense mutations. Mutation events (i.e. bin variable) or mutation frequencies were calculated based on study participants harboring at least one of non-silent mutations, following our previous work19. A recurrent mutation was defined as a non-silent mutation of the same amino acid residue which was observed in at least five specimens.

Mutation Analysis in Microsatellite Loci

Following with previous literature20, microsatellite instability (MSI) was examined using a total of 2,539 target microsatellite loci located in within or near the exome regions. The number of microsatellite loci that were altered by somatic mutations were counted for each sample.

Mutation Signature Analysis

The computational framework SigProfiler was used for mutational signature analysis across our 227 sample cohort21. We first generated mutational matrices of somatic mutations using the tool SigProfilerMatrixGenerator. Based on these mutational matrices, we analyzed mutational signature using the tool SigProfilerExtractor. Similar to our previous analysis of mutational signatures19, 22, 23, we analyzed single base substitutions (SBS) using 96 substitution classifications that included six classes of base substitution and their immediately flanking bases. The significant mutation signatures were reported using the default threshold within SigProfilerExtractor, and their annotaton was based on the the known mutation signatures identified from the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC).

Cancer Driver Gene Prediction

To identify the potential driver genes, we evaluated significantly mutated genes based on the using the MutSigCV algorithm according to the recommended practices. Briefly, we calculated the mutation category for each mutation with an in-house Perl script. We then downloaded three reference files including mutation_type_dictonary_file.txt, gene.covariates.txt, and exome_full192.coverage.txt, from the Broad Institute for this analysis. We assigned four translational effects (silent, non-silent, noncoding, and null) for each mutation based on the definition from the file “mutation_type_dictionary_file.txt”. Three covariates for each gene, including gene expression, DNA replication time, and HiC statistic were used to adjust mutation rate. The identification of putative cancer driver was implemented in the GenePattern platform. In addition, we also applied WITER for detection of cancer driver genes using the recommended parameters24. Final OTSCC cancer driver genes were selected if q < 0.01 with the MutSigCV algorithm and a relative relax cutoff at Benjamini and Hochberg adjusted P value < 0.1 in the WITER method.

Statistical Analysis

Early onset OTSCC was defined as OTSCC diagnosed at younger than age 50 based on a recent study of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data that showed OTSCC incidence was increasing among patients younger than 50 years of age7. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were compared by age of onset using Chi-squared test. To evaluate whether early onset OTSCC is genetically distinct from typical onset OTSCC, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the mutational burdens of non-silent and missense mutations between these two disease subsets. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the mutation frequency in putative cancer genes between early and typical onset OTSCC. In addition, linear regression analysis was performed on counts of microsatellite loci mutations and mutations from each mutation signature as discussed above. These regression analyses were adjusted for potential confounders, including smoking and chewing tobacco use history. Analyses were also performed on samples grouped by both age of onset and tobacco use status (never vs. ever). A P value < 0.05 for a two-tailed test was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using R package.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 227 OTSCC specimens were included in this study; 107 early onset (< 50 years of age at diagnosis) and 120 typical onset OTSCC (Table 1). For all cases combined, the majority was male (60.5%) with a tobacco use history (53.3%), overall stage III/IV disease (70.5%), and median age of 51.2 years (range: 19 to 87 years). There were no significant differences in gender or stage between early onset and typical onset OTSCC. Significantly fewer patients with early onset OTSCC had a history of any tobacco use (41.1% vs. 64.2%, P = 0.001). Patients with early onset OTSCC were significantly less likely to report a history of cigarette smoking (26.2% vs. 59.2%, P < 0.001); yet, were more likely to report chewing tobacco use (20.6% vs. 6.7%, P = 0.019).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | All OTSCC | Early onset (< 50 yrs) |

Typical onset (≥ 50 yrs) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 227 | N = 107 | N = 120 | ||

| No. patients (%) | No. patients (%) | No. patients (%) | ||

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | ||||

| Mean (Range) | 51.2 (19-87) | 37.6 (19-49) | 63.3 (50-87) | NA |

| Overall stage | ||||

| I | 28 (12.3) | 16 (15.0) | 12 (10.0) | 0.448 |

| II | 37 (16.3) | 18 (16.8) | 19 (15.8) | |

| III | 41 (18.1) | 20 (18.7) | 21 (17.5) | |

| III/IV | 11 (4.8) | 7 (6.5) | 4 (3.3) | |

| IV | 108 (47.6) | 45 (42.1) | 63 (52.5) | |

| Unavailable | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 138 (60.8) | 60 (56.1) | 78 (65.0) | 0.169 |

| Female | 89 (39.2) | 47 (43.9) | 42 (35.0) | |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Never | 114 (50.2) | 70 (65.4) | 44 (36.7) | < 0.001 |

| Ever | 99 (43.6) | 28 (26.2) | 71 (59.2) | |

| Unavailable | 14 (6.2) | 9 (8.4) | 5 (4.1) | |

| Chewing tobacco history | ||||

| Never | 69 (30.4) | 33 (30.8) | 36 (30.0) | 0.019 |

| Ever | 30 (13.2) | 22 (20.6) | 8 (6.7) | |

| Unavailable | 128 (56.4) | 52 (48.6) | 76 (63.3) | |

| Tobacco history | ||||

| Never | 95 (41.9) | 56 (52.3) | 39 (32.5) | 0.001 |

| Ever | 121 (53.3) | 44 (41.1) | 77 (64.2) | |

| Unavailable | 11 (4.8) | 7 (6.5) | 4 (3.3) | |

| Alcohol use history | ||||

| Never | 49 (21.6) | 29 (27.1) | 20 (16.7) | 0.683 |

| Ever | 49 (21.6) | 27 (25.2) | 22 (18.3) | |

| Unavailable | 129 (56.8) | 51 (47.7) | 78 (65.0) |

Abbreviations: IQR: interquartile range

Discovery of Putative Cancer Driver Genes

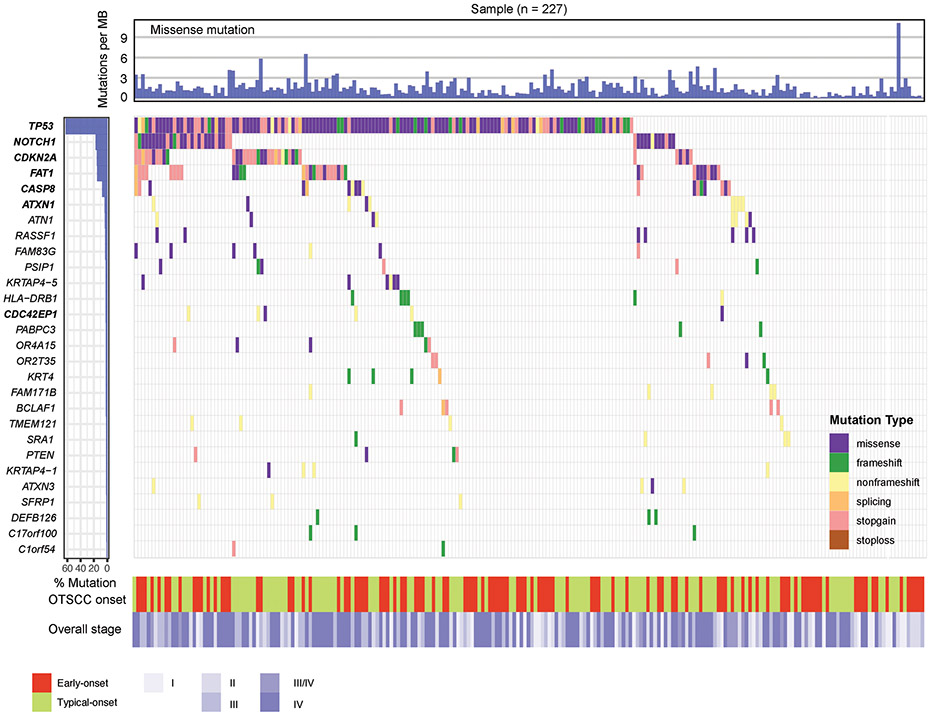

A total of 14,666 non-silent mutations including 12,058 missense, 1,355 frameshift/non-frameshift, 266 splicing, and 987 nonsense mutations were identified. Sequencing depth from the included studies is included in Supplelemental Table 1. Seven putative cancer driver genes were identified using the MutSigCV and WITER tool: TP53, NOTCH1, CDKN2A, FAT1, CASP8, ATXN1, and CDC42EP1 (Figure 1). Of these, two genes (ATXN1, and CDC42EP1) have not been previously reported in oral tongue or oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 1. Mutation landscape of the identified putative cancer-driver genes in OTSCC.

The color filled boxes denotes different mutation type. On the left of the panel, the identified putative cancer-driver genes are higlighted in bold. Colors at the bottom refer to OTSCC onset (early or typical onset) and overall cancer stage (I, II, III, III/IV, or IV).

Of these seven putative OTSCC cancer drivers genes, TP53 had the highest frequency of non-silent mutations, occurring in 143 (63.0%) OTSCC specimens. Sixty-four of these specimens carried at least one truncating mutation in TP53. NOTCH1 had the second highest frequency of non-silent mutations (17.6%) in OTSCC specimens followed by CDKN2A (15.9%), FAT1 (15.4%), CASP8 (7.9%), ATXN1 (4.0%), and CDC42EP1 (2.6%). CDKN2A and FAT1 had slightly higher incidences of truncating mutations (27 and 26 OTSCC specimens respectively), followed by NOTCH1 (14), CASP8 (11), ATXN1 (7), and CDC42EP1 (4). Overall, 175 OTSCC specimens (77%) carried missense and/or truncating mutations in at least one of these seven putative OTSCC driver genes.

Recurrent Somatic Mutations in the Putative Cancer Driver Genes

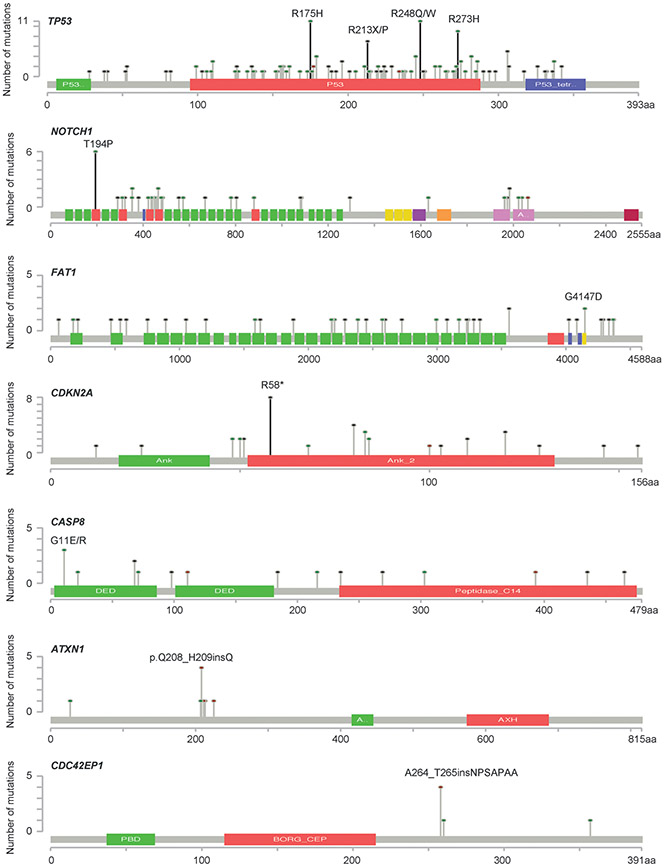

Six recurrent mutations were observed in the three putative OTSCC driver genes. These included four mutations in TP53 (p.R273H, p.R248Q/W, p.R175H and p.R213*/P), one nonsense mutation in CDKN2A (p.R58*), and one missense mutation in NOTCH1 (p.T194P) (Figure 2). Five of these recurrent mutations were seen across studies, whereas the recurrent mutation in NOTCH1 was only reported in one study14 (Supplemental Table 2). Of note, a recurrent mutation in RASSF1 (p.T92P) was also observed, however, RASSF1 was not identified as an OTSCC cancer driver gene in our analysis.

Figure 2. Recurrent mutations in the cancer driver genes of OTSCC.

The landscape of somatic mutations for each gene is shown after combing somatic mutation data from eight studies. The dominant recurrent mutation of each gene is highlighted as a black line.

Within TP53, eleven OTSCC specimens carried the missense mutation p.R175H, eight carried the missense mutation p.R248Q, three carried the missense mutation p.R248W, seven carried the missense mutation p.R273H, six carried the nonsense mutation p.R213*, and one carried the missense mutation p.R213P. All four of these mutation sites fall within the p53 DNA-binding domain (Figure 2). In total, 38 specimens (16.7%) carried at least one of these recurrent TP53 mutations. Within NOTCH1, six specimens carried the missense mutation p.T194P. Within CDKN2A, eight specimens carried the nonsense mutation p.R58* (Supplemental Table 2).

Forty-nine specimens (21.6%) carried at least one of the recurrent mutations in either TP53, CDKN2A, and NOTCH1. We observed that these recurrent mutations primarily occurred in a mutually exclusive pattern. Forty-six of the specimens carried only one unique recurrent mutation, while three specimens simultaneously carried two recurrent mutations. The pairs of simultaneous recurrent mutations were p.R273C and p.R175H in TP53, p.R175H in TP53 with p.R58* in CDKN2A, and p.R248Q in TP53 with p.R58* in CDKN2A.

Mutations in Microsatellite Loci

Fifty six of the 227 (24.7%) samples in our cohort carried mutations in MSI regions. Median mutation was one, with a range of one to four, which suggests that the MSI prevalence in OTSCC is considerably lower than in other cancer types20. When stratified by age of onset, 29.9% early onset and 20% typical onset OTSCC specimens carried at least one mutation in MSI regions.

Enriched Mutation Signatures

A total of five known mutation signatures, SBS1, SBS2, SBS5, SBS6, and SBS13, were identified to be enriched (P < 0.01) in our samples (Supplemental Figure 2). Associated factors have been identified for these mutational signatures within the COSMIC catalog, except for SBS5, which is currently unknown at this time. SBS1 is associated with spontaneous or enzymatic deamination of 5-methylcytosine to thymine. Both SBS2 and SBS13 are associated with activation of AID/APOBEC cytidine deaminases. SBS6 is associated with defective DNA mismatch repair.

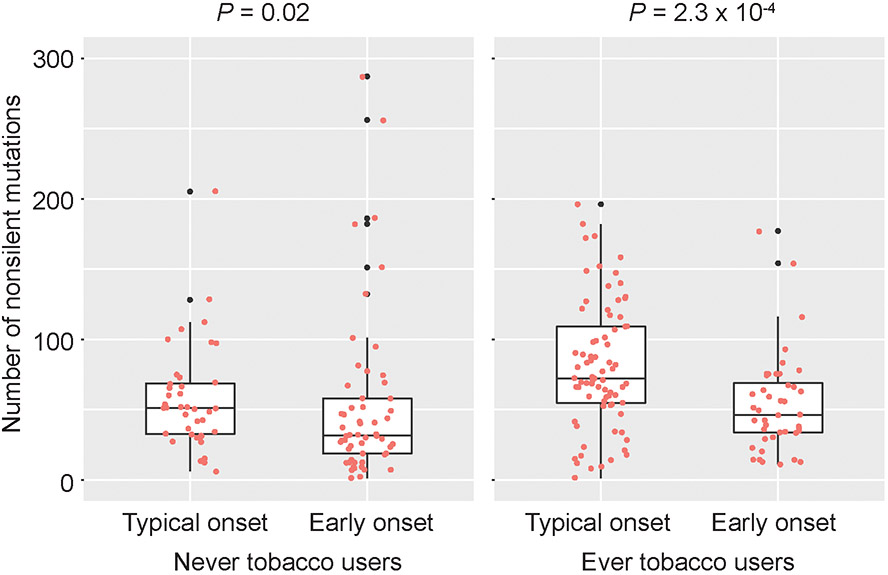

Mutation Pattern By Age of Onset and Tobacco Use

Early onset OTSCC specimens carried significantly fewer numbers of non-silent mutations (P = 2 × 10−6) compared to typical onset OTSCC, and this finding persisted (P = 5.0 × 10−3, Beta = −20.5 [95% confidence interval (CI): −34.7 to −6.3]) after adjusting for tobacco use (cigarette and chewing tobacco). When stratified by tobacco use status, patients with early onset OTSCC continued to have significantly fewer non-silent mutations, however the difference in mutation rate was greater for those who reported tobacco use (P = 0.02 for never users; P = 2.3 × 10−4 for ever users) (Figure 3). There were no associations between MSI region mutations and mutation signature with age of OTSCC onset after adjustment for covariates.

Figure 3. Somatic mutations by age of OTSCC onset.

Boxplots for the comparisons of overall non-silent and missense mutations between early onset and typical onset (Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

For the identified driver genes, early onset OTSCC carried significantly fewer non-silent mutations (P = 0.018; Beta = −0.93 [95% CI: −1.83 to −0.10]) in FAT1 than typical onset OTSCC. Yet, this significant difference did not persist after adjustment for tobacco use. No significant differences in non-silent mutations for any other putative OTSCC driver genes by age of OTSCC onset or tobacco status were observed.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to examine the somatic mutational landscape of OTSCC. We analyzed 227 OTSCC specimens from eight different sources, including data from 107 early onset specimens. We identified seven putative OTSCC driver gene, two of which have not been previously reported (ATXN1, CDC42EP1). The vast majority (82.8%) of specimens carried a missense or truncating mutation in at least one of these seven genes. TP53 had the highest incidence (63.0%) of non-silent mutations. Six recurrent mutations were observed, including four within TP53. Interestingly, all recurrent mutations observed within our analysis were within tumor suppressor genes and most were observed in specimens across the included studies. Recurrent mutations also occurred in a mutually exclusive pattern suggesting that each may play an important role in OTSCC carcinogenesis. In analyses by age, early onset OTSCC had significantly fewer non-silent mutations compared to typical onset OTSCC after correction for overall tobacco use. However, there were no significant associations between the putative OTSCC driver genes and age of OTSCC onset.

Of the seven putative OTSCC driver genes found in our analyses, five (TP53, NOTCH1, CDKN2A, FAT1, and CASP8) have been previously described as frequently mutated genes in the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) literature. TP53 is widely reported to be the most frequently mutated gene in non-HPV or smoking-related HNSCC, as well as oral cavity SCC (mutation rates: 43 to 86%)25-27. An equal percentage of non-silent TP53 mutations were seen in 67 early onset (62.6%) OTSCC specimens and 75 typical onset (62.5%) OTSCC specimens. Of the recurrent TP53 mutations, residues R248 and R273 lie within the DNA-binding domain whereas R175 has a key role in the maintaining the structural integrity of the DNA-binding surface28. These three mutations are the three most frequently mutated in human cancer as reported by the International Agency for Research on Cancer TP53 Database29 and in HNSCC as reported by the TCGA30. The mutation p.R175H has been reported to be a high risk mutation in HNSCC31, however this mutation was not associated with age of onset in our analyses.

TP53 is a tumor suppressor gene which regulates multiple downstream pathways involved in metabolism, cell-cycle arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis30. Loss of function mutations in TP53 are often central to carcinogenesis and have been shown to occur early in the HNSCC disease process, even within dysplastic lesions30. Certain TP53 mutations can also promote dominant-negative activity in which the mutant p53 protein undergoes oligomerization with wild-type p5330. However, given that the recurrent mutations observed in our study only occurred within previously classified tumor suppressor genes, we propose that these mutations confer gain of function activities in which these genes act as oncogenes rather than tumor suppressors. In fact, multiple studies have demonstrated gain of function in TP53 with the recurrent mutations observed in our study (R175H, R273H, and R248Q)30. These mutations promote invasive tumor growth and resistance to various chemotherapeutic agents including cisplatin30.

CDKN2A is another gene with near universal inactivation in non-HPV-related HNSCC27. One study reported CDKN2A mutation rates of 94% in oral cavity cancer, but in another study, rates were much lower (17.5%) and similar to those found in our analyses25, 26. NOTCH1 is involved in the squamous differentiation Notch pathway and is reported to act as tumor suppressor in oral cavity carcinogenesis26. Whereas mutations rates in NOTCH1 within oral cavity SCC (9 to 29.2%) and our cohort of OTSCC were similar, broad disruptions in genes across the Notch pathway were not observed in our analyses25, 26.

A previous genomic study by Pickering et al. proposed four major driver pathways of oral cavity SCC: TP53, Notch, cell cycle (CDKN2A, CCND1), and mitogenic signaling (EGFR, HRAS, PI3K)26. Three of these pathways were observed as prime drivers of OTSCC in this analysis, while the mitogenic signaling pathway was notably absent. Pickering et al. noted two additional genes prominent in oral cavity SCC, FAT1 and CASP8. FAT1 encodes a large transmembrane protein within the cadherin family and is involved in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. This plays a role in cell to cell signaling, differentiation, and control of cell growth32. Within HNSCC, CASP8 was reported to be preferentially seen within oral cavity subsites and some have proposed that CASP8 and FAT1 mutations cluster together25, 26. Although FAT1 and CASP8 mutations were observed as possible driver genes in this OTSCC cohort, they were not often found to exist simultaneously.

Our study identified two novel OTSCC driver mutations that have not been previously described in OTSCC or oral cavity SCC: ATXN1 and CDC42EP1. ATXN1 encodes a chromatin-binding protein which represses an important transcription factor within the Notch pathway33 and plays a role in extracellular matrix remodeling through regulation of matrix metallopeptidases34. In cervical cancer cells, one study demonstrated that ATXN1 functions as an oncogene by acting on the downstream target cyclin D1 and promoting the G0/G1 to S transition35. In both cervical cancer and colorectal adenocarcinoma, alterations of ATXN1 have been linked to increased cancer metastasis, likely though promotion of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) of cancer cells36, 37. This transition occurs as the tumor microenvironment becomes more hypoxic during tumor growth, which decreases ATXN1 levels, thereby promoting the Notch pathway and increasing cellular invasion34, 35. Taken together, these findings support that ATXN1 has a time-dependent role in cancer development. During tumorigenesis, it acts as a promoter of mitosis, but as the tumor enlarges and becomes more hypoxic, ATXN1 levels decrease and lead to increased cellular invasion. Eight of nine specimens with non-silent ATXN1 mutations were from patients with overall stage III or IV disease, therefore, we propose that ATXN1 mutations in OTSCC are involved in the EMT and cancer metastasis (Supplemental Table 4).

CDC42 is a family of Rho GTPases which regulates cytokinesis, cytoskeletal remodeling, and cell polarity38. CDC42EP1-5 (Borg) are a series of effector proteins that interact with CDC42 GTPases, and they have been hypothesized to play a role in the formation of actin-containing structures at the leading edge of migrating fibroblasts and epithelial cells38. The role of CDC42EP genes in cancer has yet to be defined. Overexpression of CDC42EP2 has been seen in HNSCC and is associated with changes consistent with increased cellular motility39. CDC42EP3 and CDC42EP5 expression are seen in the cancer-associated fibroblast phenotype and keratinocyte EMT phenotype respectively38, 40. TGF-β-induced EMT of keratinocytes leads to increased CDC42EP3 expression38. However, to date, our study is the first to comment on a relationship between CDC42EP1 and cancer development.

Although they have not been experimentally validated, we feel that ATXN1 and CDC42EP1 are likely to be cancer driver genes in a small proportion of OTSCC. ATXN1 mutations were mutually exclusive of NOTCH1 mutations, as only one of nine specimens with a non-silent ATXN1 mutation also carried a non-silent NOTCH1 mutation (Supplemental Table 4). Although not defined as recurrent mutations using our nomenclature, the same non-frameshift deletions in both ATXN1 at c.627 and CDC42EP1 at c.758 were observed in three and four samples, respectively (Supplemental Table 4).

This is also the first study to suggest that early onset OTSCC may be genetically distinct from typical onset OTSCC. While the individual studies included in this consortium previously reported that early and typical onset OTSCC were genomically similar10, 14, 16, 17, our larger meta-analysis suggests that early onset OTSCC has a significantly lower mutational burden that cannot be explained by differences in tobacco use. A lower overall mutation burden has also been observed in HPV-positive OPSCC – another head and neck cancer that was first described as increasing among younger birth cohorts. Although HPV-positive OPSCC shares similarities with early onset OTSCC in terms of overall mutation rate, HPV-positive OPSCC specimens tend to have infrequent TP53 or CDKN2A mutations27. Several studies have looked for possible involvement of HPV in OTSCC, but results have shown that only around 5% of OTSCC specimens have detectable HPV9, 41, 42. Additionally, broader transcriptome searches for other possible viruses have yet to yield any substantive results9. Thus, the underlying cause for the rise in early OTSCC remains enigmatic.

Although our analysis presents the largest genomic cohort of OTSCC to date, some limitations should be noted. Sequencing platform and data processing varied across the included studies (Supplemental Table 1), however, extensive quality control procedures were performed by original study authors for each included set of sequencing data. To evaluate whether our results were affected by somatic mutations from particular samples from different studies, we additionally filtered samples with less than five or ten silent mutations for sensitivity analyses. In these sensitivity analyses, we identified the same cancer driver genes, suggesting that our results were reliable. Furthermore, the six recurrent mutations of the OTSCC cancer driver genes were observed across multiple of the included studies (Supplemental Table 2). It is also important to note that this study included a large proportion of specimens from patients with advanced stage disease (47.6% stage IV), which raises the concern that some of our observed mutations may be passenger mutations instead of mutations involved in carcinogenesis. This also limits our ability to understand the molecular progression of these tumors, and further work is needed in this area. Our analyses lack specific tobacco use data, in terms of both duration and amout of use, and were limited to analyses by never vs. ever tobacco use status. HPV status was available for less than half (105 of 227 [46.3%]) of the specimens in our cohort and the method of HPV detection varied across the included studies. For these reasons, we were unable to reliably comment on the rates of HPV in OTSCC. We also lacked information on OTSCC recurrence and disease-specific survival and are unable to correlate the observed mutations with patient outcomes.

In conclusion, our results suggest that early onset OTSCC may be a distinct subtype of OTSCC; yet further study is needed. While this is the largest study to investigate the mutational landscape of OTSCC, additional larger studies aimed at compiling robust risk factor, clinical, and sequencing data are needed to better understand genetic the underpinning of this cancer as well as to identify possible factors underlying the increasing incidence among younger birth cohorts.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 2. A list of recurrent mutations from the identified putative cancer driver genes.

Supplemental Table 3: A list of identified cancer driver genes at q < 0.01 using MutSigCV and Benjamini and Hochberg adjusted P value < 0.1 using WITER.

Supplemental Table 4: Non-silent mutations of the identified putative cancer driver genes for each sample.

Supplemental Table 5: Results from the comparison of the mutation frequency in putative cancer genes between early onset and typical onset.

Supplemental Table 1: A list of included studies

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) K07CA218247 (PI: Krystle Kuhs)

List of Abbreviations

- OTSCC

oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma

- OPSCC

oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- WES

whole exome sequencing

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- SCOTC

Sequencing Consortium of Oral Tongue Cancer (SCOTC)

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- SBS

single base substitution

- HNSCC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- EMT

epithelial to mesenchymal transition

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Bilano V, Gilmour S, Moffiet T, et al. Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990-2025: an analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO Comprehensive Information Systems for Tobacco Control. Lancet. 2015;385: 966–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamal A KB, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, Graffunder CM. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [serial online] 2016;65:1205–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31: 4550–4559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26: 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta B, Johnson NW, Kumar N. Global Epidemiology of Head and Neck Cancers: A Continuing Challenge. Oncology. 2016;91: 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng JH, Iyer NG, Tan MH, Edgren G. Changing epidemiology of oral squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: A global study. Head Neck. 2017;39: 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tota JE, Anderson WF, Coffey C, et al. Rising incidence of oral tongue cancer among white men and women in the United States, 1973-2012. Oral Oncol. 2017;67: 146–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus-Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33: 3235–3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell BR, Netterville JL, Sinard RJ, et al. Early onset oral tongue cancer in the United States: A literature review. Oral Oncol. 2018;87: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickering CR, Zhang J, Neskey DM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue in young non-smokers is genomically similar to tumors in older smokers. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20: 3842–3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boot A, Ng AWT, Chong FT, et al. Identification of novel mutational signatures in Asian oral squamous cell carcinomas association with bacterial infections. bioRxiv. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li R, Faden DL, Fakhry C, et al. Clinical, genomic, and metagenomic characterization of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma in patients who do not smoke. Head Neck. 2015;37: 1642–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan N, Gupta S, Palve V, et al. Integrated analysis of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma identifies key variants and pathways linked to risk habits, HPV, clinical parameters and tumor recurrence. F1000Res. 2015;4: 1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upadhyay P, Gardi N, Desai S, et al. Genomic characterization of tobacco/nut chewing HPV-negative early stage tongue tumors identify MMP10 asa candidate to predict metastases. Oral Oncol. 2017;73: 56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanna GJ, Woo SB, Li YY, Barletta JA, Hammerman PS, Lorch JH. Tumor PD-L1 expression is associated with improved survival and lower recurrence risk in young women with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47: 568–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu X, Coates PJ, Boldrup L, et al. Copy number variation: A prognostic marker for young patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019;48: 24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vettore AL, Ramnarayanan K, Poore G, et al. Mutational landscapes of tongue carcinoma reveal recurrent mutations in genes of therapeutic and prognostic relevance. Genome Med. 2015;7: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38: e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Z, Wen W, Beeghly-Fadiel A, et al. Identifying Putative Susceptibility Genes and Evaluating Their Associations with Somatic Mutations in Human Cancers. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105: 477–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, et al. Landscape of Microsatellite Instability Across 39 Cancer Types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergstrom EN, Huang MN, Mahto U, et al. SigProfilerMatrixGenerator: a tool for visualizing and exploring patterns of small mutational events. BMC Genomics. 2019;20: 685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Z, Wen W, Bao J, et al. Integrative genomic analyses of APOBEC-mutational signature, expression and germline deletion of APOBEC3 genes, and immunogenicity in multiple cancer types. BMC Med Genomics. 2019;12: 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z, Wen W, Cai Q, et al. From tobacco smoking to cancer mutational signature: a mediation analysis strategy to explore the role of epigenetic changes. BMC Cancer. 2020;20: 880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang L, Zheng J, Kwan JSH, et al. WITER: a powerful method for estimation of cancer-driver genes using a weighted iterative regression modelling background mutation counts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47: e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su SC, Lin CW, Liu YF, et al. Exome Sequencing of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Reveals Molecular Subgroups and Novel Therapeutic Opportunities. Theranostics. 2017;7: 1088–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pickering CR, Zhang J, Yoo SY, et al. Integrative genomic characterization of oral squamous cell carcinoma identifies frequent somatic drivers. Cancer Discov. 2013;3: 770–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015;517: 576–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joerger AC, Ang HC, Fersht AR. Structural basis for understanding oncogenic p53 mutations and designing rescue drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103: 15056–15061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olivier M, Eeles R, Hollstein M, Khan MA, Harris CC, Hainaut P. The IARC TP53 database: new online mutation analysis and recommendations to users. Hum Mutat. 2002;19: 607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou G, Liu Z, Myers JN. TP53 Mutations in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Their Impact on Disease Progression and Treatment Response. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117: 2682–2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neskey DM, Osman AA, Ow TJ, et al. Evolutionary Action Score of TP53 Identifies High-Risk Mutations Associated with Decreased Survival and Increased Distant Metastases in Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75: 1527–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishikawa Y, Miyazaki T, Nakashiro K, et al. Human FAT1 cadherin controls cell migration and invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma through the localization of beta-catenin. Oncol Rep. 2011;26: 587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong X, Gui H, Jin F, et al. Ataxin-1 and Brother of ataxin-1 are components of the Notch signalling pathway. EMBO Rep. 2011;12: 428–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee Y, Fryer JD, Kang H, et al. ATXN1 protein family and CIC regulate extracellular matrix remodeling and lung alveolarization. Dev Cell. 2011;21: 746–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang AR, An HT, Ko J, Choi EJ, Kang S. Ataxin-1 is involved in tumorigenesis of cervical cancer cells via the EGFR-RAS-MAPK signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8: 94606–94618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang AR, An HT, Ko J, Kang S. Ataxin-1 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition of cervical cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8: 18248–18259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGranahan N, Favero F, de Bruin EC, Birkbak NJ, Szallasi Z, Swanton C. Clonal status of actionable driver events and the timing of mutational processes in cancer evolution. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7: 283ra254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farrugia AJ, Calvo F. The Borg family of Cdc42 effector proteins Cdc42EP1-5. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44: 1709–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelley LC, Shahab S, Weed SA. Actin cytoskeletal mediators of motility and invasion amplified and overexpressed in head and neck cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25: 289–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farrugia AJ, Calvo F. Cdc42 regulates Cdc42EP3 function in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Small GTPases. 2017;8: 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lingen MW, Xiao W, Schmitt A, et al. Low etiologic fraction for high-risk human papillomavirus in oral cavity squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2013;49: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palve V, Bagwan J, Krishnan NM, et al. Detection of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus in Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma Using Multiple Analytes and Their Role in Patient Survival. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4: 1–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 2. A list of recurrent mutations from the identified putative cancer driver genes.

Supplemental Table 3: A list of identified cancer driver genes at q < 0.01 using MutSigCV and Benjamini and Hochberg adjusted P value < 0.1 using WITER.

Supplemental Table 4: Non-silent mutations of the identified putative cancer driver genes for each sample.

Supplemental Table 5: Results from the comparison of the mutation frequency in putative cancer genes between early onset and typical onset.

Supplemental Table 1: A list of included studies