Abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) outflow from the brain occurs through absorption into the arachnoid villi and, more predominantly, through meningeal and olfactory lymphatics that ultimately drain into the peripheral lymphatics. Impaired CSF outflow has been postulated as a contributing mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Herein we conducted near-infrared fluorescence imaging of CSF outflow into the peripheral lymph nodes (LNs) and of peripheral lymphatic function in a transgenic mouse model of AD (5XFAD) and wild-type (WT) littermates. CSF outflow was assessed from change in fluorescence intensity in the submandibular LNs as a function of time following bolus, an intrathecal injection of indocyanine green (ICG). Peripheral lymphatic function was measured by assessing lymphangion contractile function in lymphatics draining into the popliteal LN following intradermal ICG injection in the dorsal aspect of the hind paw. The results show 1) significantly impaired CSF outflow into the submandibular LNs of 5XFAD mice and 2) reduced contractile frequency in the peripheral lymphatics as compared to WT mice. Impaired CSF clearance was also evidenced by reduction of fluorescence on ventral surfaces of extracted brains of 5XFAD mice at euthanasia. These results support the hypothesis that lymphatic congestion caused by reduced peripheral lymphatic function could limit CSF outflow and may contribute to the cause and/or progression of AD.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal fluid outflow, fluorescence imaging, intrathecal, lymphatic system

INTRODUCTION

Although the etiology of the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is not definitely known, misfolding, aggregation, and brain deposition of misfolded protein aggregates in the form of amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary tangles are considered triggering factors of the pathology [1]. Amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides with 40 and 42 amino acids result from the proteolytic processing of the amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP) and form the major component of amyloid plaques deposited in the brain of AD patients [2]. It has been hypothesized that Aβ accumulation results from an imbalance between Aβ production and its clearance [1, 2]. Aβ is removed by various mechanisms, including degradation by enzymes [3-6], the uptake by microglial or astrocytic phagocytosis [3,4], interstitial fluid (ISF) flow along smooth muscle cell basement membranes in the walls of cerebral arteries, also known as intramural periarterial drainage [7-9], and CSF absorption into the venous arachnoid villi and into peripheral lymphatic system from the perivascular and perineural compartments [1, 2, 10, 11].

Consistent with recent revisions in Starling’s law that predict minimal fluid reabsorption into venous blood vessels [12], the predominant clearance of CSF is most likely through the cribriform plate into nasal lymphatics. Previous studies in many mammals including humans show that CSF transport is observed in the perineurial compartments of the olfactory nerves external to the cranium, which merge into extensive lymphatic networks associated with the submucosa of the olfactory epithelium, ethmoid turbinates, and adjacent nasal septum following injection of the contrast agent into the cranial subarachnoid compartment [13-15]. CSF is also transported from the sub-arachnoid space into the perivascular (Virchow-Robin) arterial compartments wherein the water channel protein, Aquaporin-4 (AQP4), located on the foot processes of astrocytes, is thought to facilitate convective flow that exchanges macromolecules with ISF across the brain parenchyma before emptying into the peri-venous compartments that empty into the cervical lymph nodes (LNs) [10]. These astroglial water channels are termed the “glymphatics” because they act as a “pseudo” lymphatic system by cleansing excess macromolecules from the interstitial space. The glymphatic pathway may be important for Aβ clearance [10]. Glymphatic transport has been shown to be suppressed in double transgenic mice overexpressing mutated forms of the genes for human APP and presenilin 1 (PS1), both genes associated to familial forms of AD [16]. ISF is also known to drain out of the brain along the intramural periarterial drainage to cervical LNs [17]. Regardless of how CSF is cleared through cribriform or meningeal lymphatics or through these newly discovered glymphatic pathways, CSF outflow from the brain is directed to the LNs draining the head and neck region, which constitute 1/3 of the LNs within the peripheral lymphatic system [18]. Peripheral lymphatics constitute a functional unidirectional vascular system that is responsible for draining collected interstitial fluid (lymph) and waste products to the venous circulation for processing. Lymphatic transport occurs via extrinsic (passive) mechanisms as well as intrinsic contractile activity of lymphangions, which consist of lymphatic vessel segments bounded upstream and downstream with valves that open and close in concert smooth muscle contraction to propel lymph unidirectionally, often against gravity through the lymphatic network draining into the supraclavicular vein. Lymphangion activity can be impaired by pro-inflammatory cytokines [19], leading to lymphatic congestion or regional edema. Whether impaired peripheral lymphatic function and congestion reduces CSF outflow in AD remains to be demonstrated.

In this study, we show altered CSF clearance through the lymphatics in 5XFAD transgenic mice and impaired peripheral lymphatic function as compared to their age-matched wild-type (WT) littermates. Our study suggests that lymphatic congestion that is associated with defective peripheral lymphatic pump function could cause or further impair CSF outflow and contribute to the progression of AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

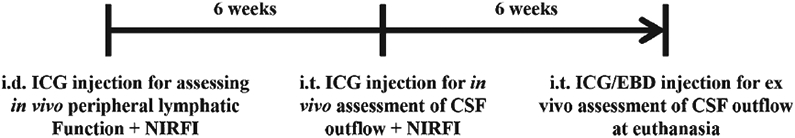

Animals were maintained in a specific pathogen-free mouse facility accredited by The Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center-Houston. All experiments were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines. 5XFAD mice overexpress mutant human APP(695) with the Swedish (K670N, M671L), Florida (I716V), and London (V717I) familial AD mutations along with human PS1 harboring M146L and L286V mutations both directed towards neurons [20, 21]. Six to eight-month-old female and male 5XFAD and WT mice were housed and fed irradiated pelleted food and purified, acidified water. For all procedures, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and maintained at 37°C on a warming pad. Animals were clipped and residual hair removed using depilatory cream (Nair, Church & Dwight Co., Inc.) 24 h before imaging. Peripheral lymphatic function was first imaged following intradermal (i.d.) injection of indocyanine green (ICG). Following 1.5 months after i.d. administered ICG had completely cleared from the body, intrathecal (i.t.) injection of ICG was conducted for imaging, followed immediately with another i.t. ICG injection 1.5 months later that contained Evan’s blue dye (EBD) to visualize the uptake into the brain upon euthanasia. Figure 1 details the animal protocol.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of animal experimentation.

Tracer administration

For peripheral lymphatic imaging, ICG (0.25 mg; Akorn, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL) was dissolved in a mixture of distilled water and 0.9% sodium chloride in a volume ratio of 1:9 and 2 μl of ICG injected i.d. to the dorsal aspect of the left foot using 34-gauge needles. For imaging CSF outflow, the fifth-sixth lumbar vertebrae (L5-L6) area was disinfected using betadine and a small incision (~1 cm) made between the L5 and L6 vertebrae for i.t. ICG injection [22]. A 31-gauge needle (BD Ultra-Fine™ II Short Needle or Hamilton syringe) was inserted between L5 and L6 vertebrae and a tail flick response was observed as indication of correct position of the needle in the intradural space [22]. I.t. injection of 10 μl of ICG or, at the final imaging session, of a mixture of ICG (5 μl and Evan’s blue dye (5 μl 2%) was performed immediately after a tail flick. The incision was closed with surgical glue (3M Vetbond, 3M Animal care products). The injection site was covered with the black electrical tape to prevent oversaturation of the camera.

In vivo and ex vivo imaging

Near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent images were acquired immediately after and for up to 20 min after i.d. ICG injections using a custom-built NIR fluorescence imaging (NIRFI) system as described previously [23-26]. One and half months after i.d. injection, non-invasive NIRFI was also performed 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h after i.t. ICG injection. About one and half months later, a second i.t. injection of a mixture of ICG and EBD was performed and 30 min afterward, the animal was euthanized and the brain was dissected and imaged. To achieve a greater magnification for NIRFI, a macrolens (Infinity K2/SC video lens, Edmund Optics Inc.) was used. The camera exposure time for NIRFI was 200 ms for in vivo and 100 ms for ex vivo imaging.

Analysis of lymphatic vessel function and CSF outflow to LNs

ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC) was used to analyze the fluorescence imaging data in the following manner. To assess lymphatic contractility, a fixed region of interest (ROI) in a fluorescent afferent lymph channel was defined on fluorescence images. The mean of the fluorescence intensity within each ROI in each fluorescence image was then calculated and plotted as a function of imaging time as previously described [23-26]. To test if CSF outflow to peripheral LNs is affected in AD mice, average NIR fluorescent radiance (mW·cm−2·sr−1) in submandibular LNs (SMLNs) were measured [27].

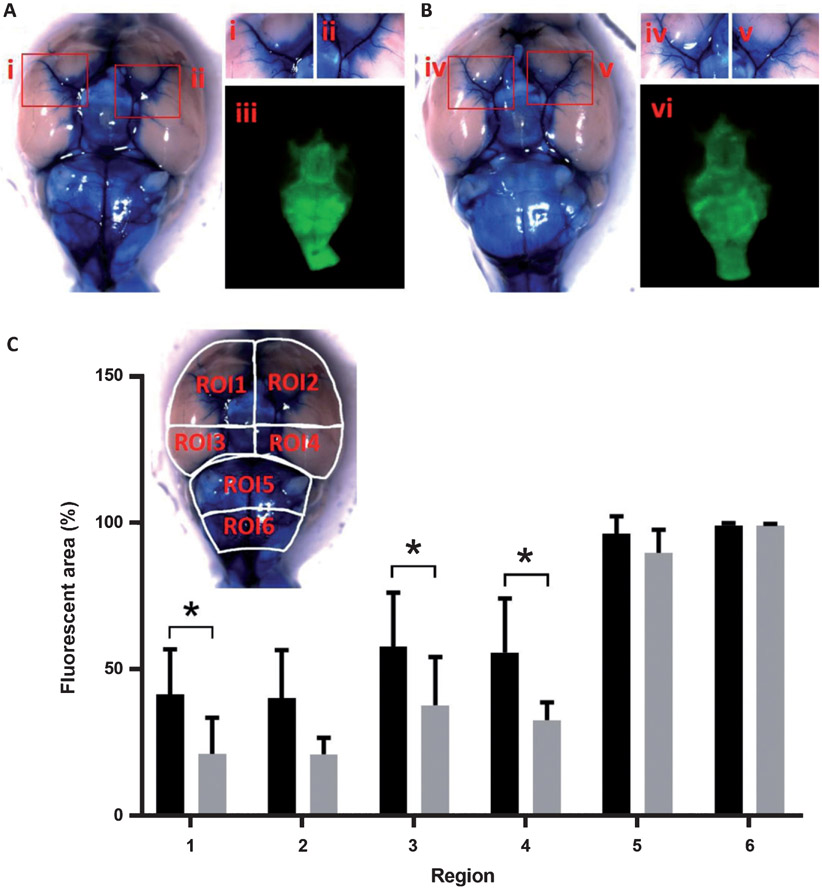

Assessment of CSF spread on ventral surface of the brain

The spread of ICG in the base of the brain was quantified at euthanasia. NIR fluorescent images were thresholded at the same fluorescence radiance and then converted into binary images using ImageJ using the procedures described by others [28]. Briefly, the ventral surface of the brain was segmented into 6 ROIs. Quadrants ROI1 through ROI4 were defined rostrally to the pons and based on the division of the ventral surface by sagittal midline and a perpendicular line passing through the hypophyseal stalk. ROI5 was defined from the caudal to the rostral border of the pons and ROI6 from the caudal border of the brain-stem to the caudal border of the pons. The percentage of the area of each ROI with ICG fluorescence was quantified.

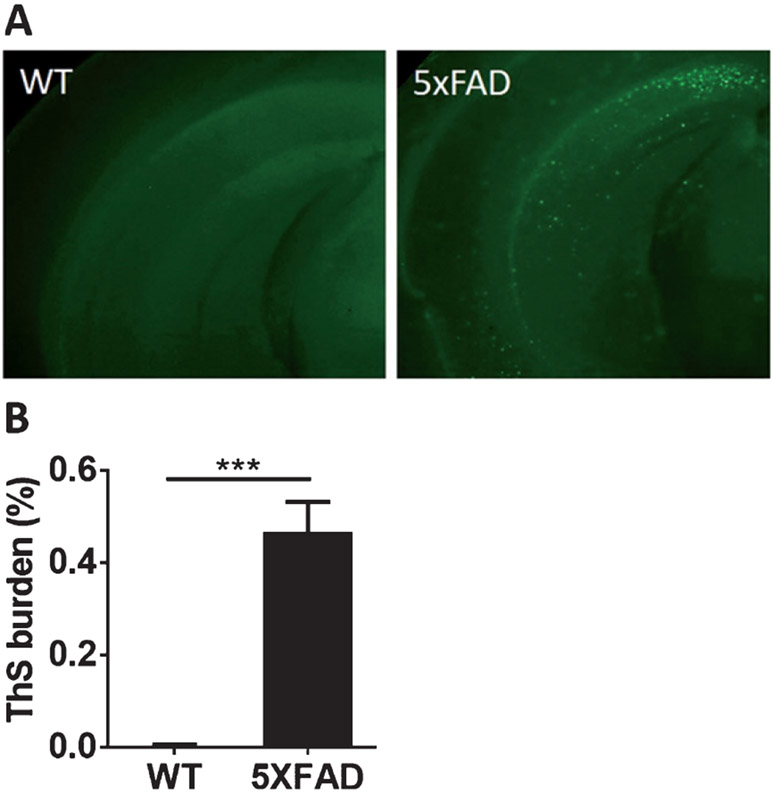

Thioflavine S staining and burden quantification

For evaluation of neuropathological changes, 5XFAD and WT animals were sacrificed. The brain was collected and fixed in formalin for histological analysis, as we previously described [29]. The extent of amyloid deposition was measured by image analysis using 1 mm thickness serial coronal brain slices stained with Thioflavin S (ThS) at 0.025% in ethanol 50% for 8 min. Free-floating sections were rinsed and cover slipped with mounting medium for fluorescence (Vector). Five slices per animal were analyzed. Photomicrographs of samples examined under an epifluorescent microscope (DMI6000B, Leica) were imported into ImageJ, and converted to gray scale images. Threshold intensity was used to quantify amyloid burden. Load of Aβ, defined as the area labeled per total area analyzed, was quantified.

Statistical analysis

Data was presented as average values±standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 7 (Graphpad Software, Inc). The Mann-Whitney test or t-test was used for comparisons between two groups or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test among groups. The significance level is set as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

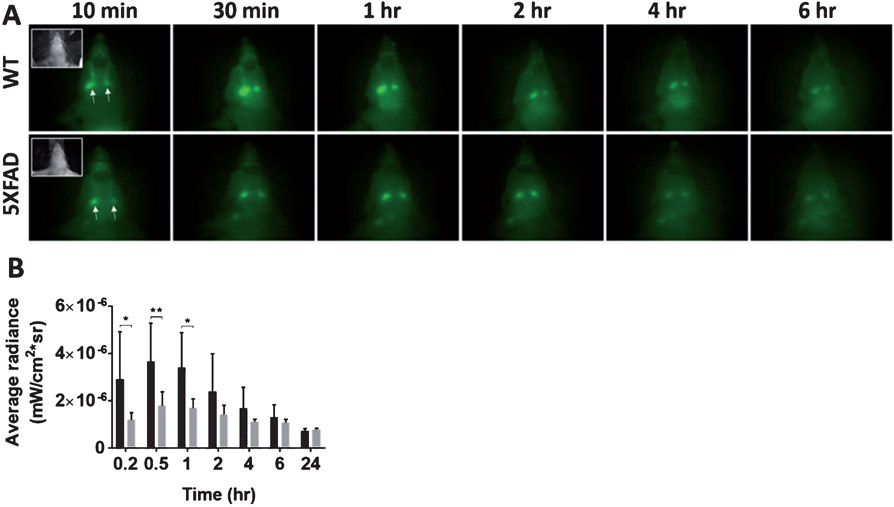

CSF outflow following i.t. injection is in impaired in AD mice

To determine whether the CSF outflow into peripheral LNs is compromised during AD neuropathology progression, 5XFAD mice with substantial amyloid burden in the brain (Fig. 2) and WT age-matched littermates were i.t. injected with ICG and imaged using NIRFI to measure lymphatic outflow. Immediately following i.t. injection, ICG transits to the subarachnoid space and through the cribriform vessels to the SMLNs, as seen from ventral NIR fluorescent images in Fig. 3A and Fig. 3B shows the average and standard deviation of calibrated fluorescence radiance (mW·cm−2·sr−1) collected from the tissue surface as a function of time after i.t. administration for 5XFAD (n = 7) and WT littermates (n = 11). The highest fluorescence radiance occurred at 0.5-h post injection in 5XFAD and age-matched WT mice and the radiance decreased over time. Significantly higher fluorescence radiance was found in WT mice than age-matched 5XFAD mice at 0.2, 0.5, and 1 h post injection, but no statistically significant difference existed after 2 h.

Fig. 2.

5XFAD mice show high ThS-positive Aβ deposits as compared to age-matched WT mice. Epifluorescent microscopic images of ThS staining shown in the whole brains of 5XFAD and age-matched WT mice (A). The burden of ThS-positive amyloid plaques was significantly higher in AD mice compared with WT mice (B). (n = 3–7 animals/group, five sections per animal).***p < 0.0001. Error bars are SE of the mean.

Fig. 3.

Intrathecally injected ICG is drained to the SMLNs. To evaluate whether CSF outflow into the peripheral SMLN of AD mice is impaired, we injected ICG intrathecally into 5XFAD and WT mice. A) NIR fluorescent images in the ventral view of WT and 5XFAD mice 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 6 h after i.t. injection of ICG. Inset, white light images. Arrow, SMLNs. B) Quantification of average fluorescent radiance (mW·cm−2·sr−1) in SMLNs. *p = 0.018. **p = 0.007.

Peripheral lymphatic function following intradermal injection is impaired in AD mice

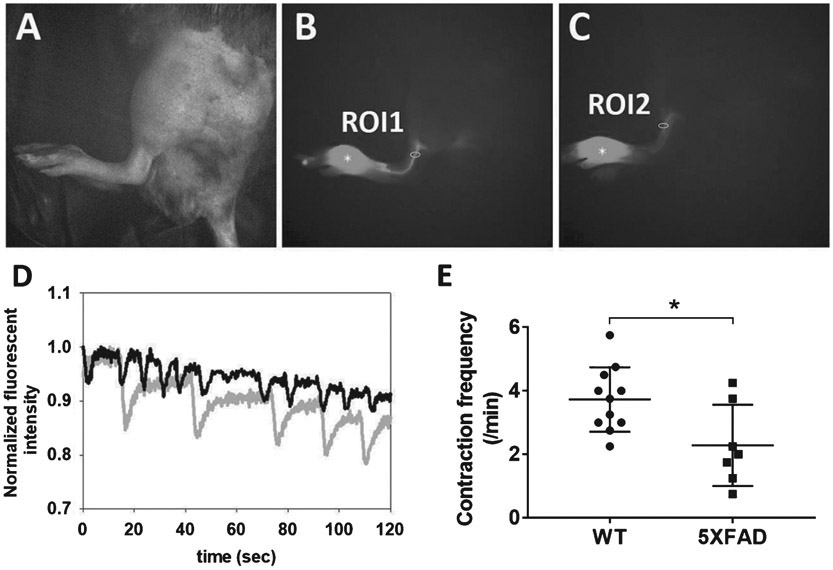

Figure 4 shows the anatomy and contractile function in the hind limbs of typical 5XFAD and WT animals. Figure 4D shows example traces of the fluorescence radiance of ROIs that emptied and refilled with ICG-laden lymph in 5XFAD (grey) and WT (black) mice. Figure 4E shows that significantly reduced lymphatic contractile activity was observed in 5XFAD mice as compared to age-matched WT mice, suggesting that in addition to impaired CSF outflow into the lymphatics, impaired peripheral lymphatic function also accompanies disease.

Fig. 4.

To evaluate whether peripheral lymphatic function in AD mice is reduced, we injected ICG intradermally to the foot of 5XFAD and WT mice. Representative white light (A) and fluorescent (B, C) images 20 mins after i.d. injection of ICG to WT (A, B) and 5XFAD (C) mice. Asterisk: ICG injection site. D) Normalized fluorescent radiance profiles as a function of time in ROI 1 (WT; black) and ROI 2 (5XFAD; grey). E) Quantification of lymphatic contraction frequency in WT (n = 11) and 5XFAD mice (n = 7). *p = 0.029.

CSF distribution on ventral surface of the brain of AD mice is limited

To follow the drainage of CSF, 5XFAD and WT animals were allowed to recover after ICG administration and, 1.5 months later, a second injection was performed. Brains were excised 30 min after i.t. injection of a mixture of ICG and EBD. Ventral surfaces were imaged to determine whether distribution of ICG/EBD in perivascular compartments is altered in 5XFAD mice. As shown in typical images of WT (Fig. 5A) and 5XFAD (Fig. 5B) mouse brains, we observed distribution of EBD in perivascular compartments of the WT mouse brain, whereas less perivascular distribution of EBD was detected in age-matched 5XFAD mice. ICG diffusion was measured in 6 different regions of interest (ROI), including the right (ROI1) and left (ROI2) frontal and temporal cortical areas that contain the anterior and middle cerebral artery, the right (ROI3) and left (ROI4) temporal cortical areas containing the internal carotid, and the medullar region that contains the basilar, posterior cerebral, and anterior cerebellar arteries (ROI5), and the anterior-inferior cerebellar and vertebral arteries (ROI6) [28]. Quantification from ex vivo NIRFI (Fig. 5Aiii, 5Bvi) showed significantly reduced fluorescent area in ROIs 1, 3, and 4 in 5XFAD mice when compared to age-matched WT mice (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Intrathecally injected ICG is distributed along the perivascular subarachnoid space over the ventral surface of the brain. To quantitatively and qualitatively evaluate whether CSF distribution in the base of the brain of AD mice is limited, we injected a mixture of EBD and ICG intrathecally to 5XFAD and WT mice. Ex vivo EBD color images showing perivascular distribution of EBD and ICG in WT (A) and 5XFAD (B) mice. Red boxes in A and B in brains are represented at higher magnification (i, ii, iv, and v). The corresponding NIR fluorescent images were also shown in iii and vi for WT and 5XFAD mice, respectively. C) Quantification of percentage of the average area of ICG distribution in ROIs 1 through 6 (inset) on the ventral brain of WT (n = 8) and 5XFAD (n = 5) mice. *p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Because the central nervous system is devoid of a lymphatic vasculature, the pathological accumulation of cellular waste products has been attributed to defects in 1) blood-brain barrier clearance, 2) intracellular degradation and autophagy, and/or 3) extracellular degradation and phagocytosis. Herein, we have shown that CSF distribution in the brain and CSF drainage into the peripheral lymphatics is impaired in a well-established animal model of AD compared to age-matched WT littermates. More strikingly, we have also found that in these same AD animals, the peripheral contractile pumping activity is also diminished when compared to age-matched WT littermates, suggesting that impaired CSF outflow into the lymphatics could be caused by systemic lymphatic congestion.

Although the mechanism for intrinsic, contractile lymphatic “pumping” remains unknown and controversial [30-32], investigators have found that lymphangion activity declines with age [33] and that inflammatory cells and mediators of inflammation impact their contractility [19, 34-39]. For example, we have shown that systemic or regional i.d. injection of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, and tumor-necrosis factor (TNF)–α acutely decreases the contractile frequency of lymphangions, an effect that can be inhibited by pre-administration of an inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) inhibitor [19]. Systemic, intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been shown to result in acute, transiently high levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α [19], which, under chronic LPS administrations, induces enhanced Aβ generation in the brains of WT mice [40]. It is well known that TNF-α is involved in the pathogenesis of AD [41] and that CSF of AD patients has been shown to have TNF-α levels 25x that of normal subjects [42]. In addition, cerebral accumulation of Aβ triggers a sustained and chronic inflammatory response that includes the activation of microglia, resident macrophages of the brain, leading to increased production of IL-6, IL-1β, NO, and iNOS, and phagocytic capacity [43-47]. When the blood-brain barrier function is compromised, as known to occur at different stages of AD [48], infiltration of peripheral macrophages further alters local pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. These pro-inflammatory cytokines may play a role in neurotoxicity, induce tau hyperphosphorylation and formation of neurofibrillary tangles [49], but upon drainage into the lymphatics may also further impede lymphatic contractile function [19], resulting in congestion and reduced CSF outflow. It is known that 9–12-month-old 5XFAD mice have extensive amyloid burden and neuroinflammation at the time our experiments were performed. As a result, CSF drainage of pre-inflammatory cytokines into the peripheral lymphatics, including from the spinal canal to sciatic lymph nodes that also drain the hind limbs, may result in impairment of the systemic lymphatic pump.

Using a transgenic mouse model expressing a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C/D trap and complete aplasia of the initial, meningeal lymphatics in the dura, Aspelund and coworkers [50] showed impaired macromolecule clearance from the parenchyma to the cervical LNs, indicating the importance of fluid entrance into the initial lymphatics and CSF clearance into the peripheral lymphatics. Impaired glymphatics [51] has also been shown to be increased with age and precedes significant Aβ deposits, further indicating the importance of CSF outflow into the lymphatics as a significant factor in the development of AD [52]. Whether neuroinflammation and amyloid deposition in AD directly causes or is caused by impaired lymphatic congestion and reduced CSF outflow remains to be investigated. Herein, we have shown that reduced CSF outflow in an AD model accompanies impaired peripheral lymphatic function. The implication of this work is that CSF outflow may be impacted by overall lymphovascular health and strategies to systemically improve peripheral lymphatic function could represent a therapeutic or even preventative strategy against AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by R56 AG057 581-01.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/19-0013r2).

REFERENCES

- [1].Huang Y, Mucke L (2012) Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell 148, 1204–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT (2011) Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 1, a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang YJ, Zhou HD, Zhou XF (2006) Clearance of amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease: Progress, problems and perspectives. Drug Discov Today 11, 931–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, Glodzik L, Butler T, Fieremans E, Axel L, Rusinek H, Nicholson C, Zlokovic BV, Frangione B, Blennow K, Menard J, Zetterberg H, Wisniewski T, de Leon MJ (2015) Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 11, 457–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hernandez-Guillamon M, Mawhirt S, Blais S, Montaner J, Neubert TA, Rostagno A, Ghiso J (2015) Sequential amyloid-beta degradation by the matrix metalloproteases MMP-2 and MMP-9. J Biol Chem 290, 15078–15091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Farris W, Mansourian S, Chang Y, Lindsley L, Eckman EA, Frosch MP, Eckman CB, Tanzi RE, Selkoe DJ, Guenette S (2003) Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta-protein, and the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 4162–4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Carare RO, Bernardes-Silva M, Newman TA, Page AM, Nicoll JA, Perry VH, Weller RO (2008) Solutes, but not cells, drain from the brain parenchyma along basement membranes of capillaries and arteries: Significance for cerebral amyloid angiopathy and neuroimmunology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 34, 131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hawkes CA, Jayakody N, Johnston DA, Bechmann I, Carare RO (2014) Failure of perivascular drainage of beta-amyloid in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain Pathol 24, 396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Albargothy NJ, Johnston DA, MacGregor-Sharp M, Weller RO, Verma A, Hawkes CA, Carare RO (2018) Convective influx/glymphatic system: Tracers injected into the CSF enter and leave the brain along separate periarterial basement membrane pathways. Acta Neuropathol 136, 139–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, Benveniste H, Vates GE, Deane R, Goldman SA, Nagelhus EA, Nedergaard M (2012) A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med 4, 147ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD, Derecki NC, Castle D, Mandell JW, Lee KS, Harris TH, Kipnis J (2015) Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 523, 337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Levick JR Michel CC (2010) Microvascular fluid exchange and the revised Starling principle. Cardiovasc Res 87, 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kida S, Pantazis A, Weller RO (1993) CSF drains directly from the subarachnoid space into nasal lymphatics in the rat. Anatomy, histology and immunological significance. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 19, 480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Johnston M, Zakharov A, Koh L, Armstrong D (2005) Subarachnoid injection of Microfil reveals connections between cerebrospinal fluid and nasal lymphatics in the non-human primate. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 31, 632–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Johnston M, Zakharov A, Papaiconomou C, Salmasi G, Armstrong D (2004) Evidence of connections between cerebrospinal fluid and nasal lymphatic vessels in humans, non-human primates and other mammalian species. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 1, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Peng W, Achariyar TM, Li B, Liao Y, Mestre H, Hitomi E, Regan S, Kasper T, Peng S, Ding F, Benveniste H, Nedergaard M, Deane R (2016) Suppression of glymphatic fluid transport in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 93, 215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Engelhardt B, Carare RO, Bechmann I, Flugel A, Laman JD, Weller RO (2016) Vascular, glial, and lymphatic immune gateways of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 132, 317–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Foldi M, Foldi E (2006) Foldi’s Textbook of Lymphology. Biotext, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Aldrich MB, Sevick-Muraca EM (2013) Cytokines are systemic effectors of lymphatic function in acute inflammation. Cytokine 64, 362–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jankowsky JL, Fadale DJ, Anderson J, Xu GM, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Lee MK, Younkin LH, Wagner SL, Younkin SG, Borchelt DR (2004) Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: Evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum Mol Genet 13, 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, Guillozet-Bongaarts A, Ohno M, Disterhoft J, Van Eldik L, Berry R, Vassar R (2006) Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: Potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci 26, 10129–10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kwon S, Janssen CF, Velasquez FC, Sevick-Muraca EM (2017) Fluorescence imaging of lymphatic outflow of cerebrospinal fluid in mice. J Immunol Methods 449, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kwon S, Price RE (2016) Characterization of internodal collecting lymphatic vessel function after surgical removal of an axillary lymph node in mice. Biomedical Optics Express 7, 1100–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kwon S, Agollah GD, Wu G, Sevick-Muraca EM (2014) Spatio-temporal changes of lymphatic contractility and drainage patterns following lymphadenectomy in mice. PLoS One 9, e106034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Burrows PE, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Rasmussen JC, Aldrich MB, Guilliod R, Maus EA, Fife CE, Kwon S, Lapinski PE, King PD, Sevick-Muraca EM (2013) Lymphatic abnormalities are associated with RASA1 gene mutations in mouse and man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 8621–8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lapinski PE, Kwon S, Lubeck BA, Wilkinson JE, Srinivasan RS, Sevick-Muraca E, King PD (2012) RASA1 maintains the lymphatic vasculature in a quiescent functional state in mice. J Clin Invest 122, 733–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhu B, Rasmussen JC, Litorja M, Sevick-Muraca EM (2016) Determining the performance of fluorescence molecular imaging devices using traceable working standards with SI units of radiance. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 35, 802–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Golanov EV, Bovshik EI, Wong KK, Pautler RG, Foster CH, Federley RG, Zhang JY, Mancuso J, Wong ST, Britz GW (2018) Subarachnoid hemorrhage - Induced block of cerebrospinal fluid flow: Role of brain coagulation factor III (tissue factor). J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 38, 793–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Moreno-Gonzalez I, Estrada LD, Sanchez-Mejias E, Soto C (2013) Smoking exacerbates amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun 4, 1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zawieja DC (2009) Contractile physiology of lymphatics. Lymphat Res Biol 7, 87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Howarth D, Burstal R, Hayes C, Lan L, Lantry G (1999) Autonomic regulation of lymphatic flow in the lower extremity demonstrated on lymphoscintigraphy in patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Clin Nucl Med 24, 383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schmid-Schonbein GW (1990) Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiol Rev 70, 987–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nagai T, Bridenbaugh EA, Gashev AA (2011) Aging-associated alterations in contractility of rat mesenteric lymphatic vessels. Microcirculation 18, 463–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].von der Weid PY, Muthuchamy M (2010) Regulatory mechanisms in lymphatic vessel contraction under normal and inflammatory conditions. Pathophysiology 17, 263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Benoit JN, Zawieja DC (1992) Effects of f-Met-Leu-Phe-induced inflammation on intestinal lymph flow and lymphatic pump behavior. Am J Physiol 262, G199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Breslin JW, Gaudreault N, Watson KD, Reynoso R, Yuan SY, Wu MH (2007) Vascular endothelial growth factor-C stimulates the lymphatic pump by a VEGF receptor-3-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293, H709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Davis MJ, Lane MM, Davis AM, Durtschi D, Zawieja DC, Muthuchamy M, Gashev AA (2008) Modulation of lymphatic muscle contractility by the neuropeptide substance P. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295, H587–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Plaku KJ, von der Weid PY (2006) Mast cell degranulation alters lymphatic contractile activity through action of histamine. Microcirculation 13, 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chatterjee V, Gashev AA (2012) Aging-associated shifts in functional status of mast cells located by adult and aged mesenteric lymphatic vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303, H693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lee JW, Lee YK, Yuk DY, Choi DY, Ban SB, Oh KW, Hong JT (2008) Neuro-inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment through enhancement of beta-amyloid generation. J Neuroinflammation 5, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Carriba P, Jimenez S, Navarro V, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Barneda-Zahonero B, Moubarak RS, Lopez-Soriano J, Gutierrez A, Vitorica J, Comella JX (2015) Amyloid-beta reduces the expression of neuronal FAIM-L, thereby shifting the inflammatory response mediated by TNFalpha from neuronal protection to death. Cell Death Dis 6, e1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tarkowski E, Liljeroth AM, Minthon L, Tarkowski A, Wallin A, Blennow K (2003) Cerebral pattern of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in dementias. Brain Res Bull 61, 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rosenberg PB (2005) Clinical aspects of inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Rev Psychiatry 17, 503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Craft JM, Watterson DM, Van Eldik LJ (2006) Human amyloid beta-induced neuroinflammation is an early event in neurodegeneration. Glia 53, 484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Benveniste EN, Nguyen VT, O’Keefe GM (2001) Immunological aspects of microglia: Relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int 39, 381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Moreno-Gonzalez I, Baglietto-Vargas D, Sanchez-Varo R, Jimenez S, Trujillo-Estrada L, Sanchez-Mejias E, Del Rio JC, Torres M, Romero-Acebal M, Ruano D, Vizuete M, Vitorica J, Gutierrez A (2009) Extracellular amyloid-beta and cytotoxic glial activation induce significant entorhinal neuron loss in young PS1(M146L)/APP(751SL) mice. J Alzheimers Dis 18, 755–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jimenez S, Baglietto-Vargas D, Caballero C, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Torres M, Sanchez-Varo R, Ruano D, Vizuete M, Gutierrez A, Vitorica J (2008) Inflammatory response in the hippocampus of PS1M146L/APP751SL mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: Age-dependent switch in the microglial phenotype from alternative to classic. J Neurosci 28, 11650–11661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zlokovic BV (2011) Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 12, 723–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yoshiyama Y, Higuchi M, Zhang B, Huang SM, Iwata N, Saido TC, Maeda J, Suhara T, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (2007) Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron 53, 337–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Aspelund A, Antila S, Proulx ST, Karlsen TV, Karaman S, Detmar M, Wiig H, Alitalo K (2015) A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med 212, 991–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kress BT, Iliff JJ, Xia M, Wang M, Wei HS, Zeppenfeld D, Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Liew JA, Plog BA, Ding F, Deane R, Nedergaard M (2014) Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Ann Neurol 76, 845–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Peng W, Achariyar TM, Li B, Liao Y, Mestre H, Hitomi E, Regan S, Kasper T, Peng S, Ding F, Benveniste H, Nedergaard M, Deane R (2016) Suppression of glymphatic fluid transport in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 93, 215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]