Abstract

Background

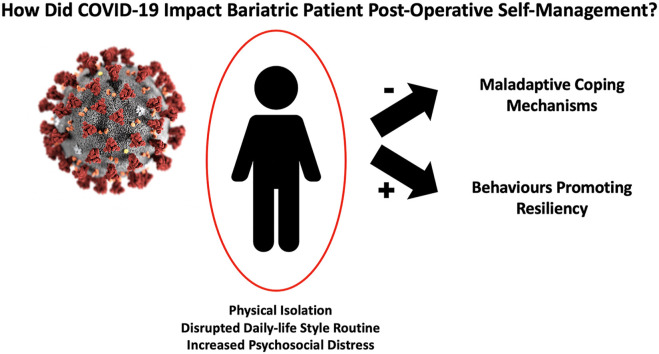

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had far reaching consequences on the health and well-being of the general public. Evidence from previous pandemics suggest that bariatric patients may experience increased emotional distress and difficulty adhering to healthy lifestyle changes post-surgery.

Objective

We aimed to examine the impact of the novel COVID-19 public health crisis on bariatric patients’ self-management post-surgery.

Method

In a nested-qualitative study, semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with 23 post-operative bariatric patients who had undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) at a Canadian Bariatric Surgery Program between 2014 and 2020. A constant comparative approach was used to systematically analyze the data and identify the overarching themes.

Results

Participants (n = 23) had a mean age of (48.82 ± 10.03) years and most were female (n = 19). The median time post-surgery was 2 years (range: 6 months–7 years). Themes describing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients’ post-bariatric surgery self-management included: coping with COVID-19; vulnerability factors and physical isolation; resiliency factors during pandemic; and valuing access to support by virtual care. The need for patients to access post-operative bariatric care during COVID-19 differed based on gender and socioeconomic status.

Conclusion

This study showed that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted patients’ ability to self-manage obesity and their mental health in a variety of ways. These findings suggest that patients may experience unique psychological distress and challenges requiring personalized care strategies to improve obesity self-care and overall well-being.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused global disruption in everyday life (Manderson & Levine, 2020). Compared to previous pandemics, the distress and uncertainty caused by the lack of an endpoint for the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant psychological impact on the general population mental health outcomes (Statistics Canada, 2020). A recent study by Rettie and Daniels in the United Kingdom, demonstrated that the prevalence of generalized anxiety, depression, and health anxiety were higher compared to that reported in previous pandemics (Rettie & Daniels, 2020). Evidence from similar pandemics such as SARS, have shown that fear of biological disasters, uncertainty, and prevailing stigma could act as barriers to proper mental health care, especially among vulnerable groups (Brooks et al., 2020; Galea, Merchant, & Lurie, 2020; Tsamakis et al., 2020). Of these groups, individuals with obesity are not only susceptible for poor outcomes if infected but also are more likely to experience increased psychosocial distress and poor obesity self-management in response to quarantine or self-isolation and sedentary lifestyle (Ghanemi, Yoshioka, & St-Amand, 2020; Hussain, Mahawar, & El-Hasani, 2020; Kassir, 2020; Mattioli, Pinti, Farinetti, & Nasi, 2020).

The impact of COVID-19 on bariatric surgery and limited access to post-operative care during this pandemic remains uncertain. However, a number of survey studies and editorials have already raised concerns over the limited access to obesity care during this pandemic (Ghanemi et al., 2020; Hussain et al., 2020; Mattioli et al., 2020; Mitchell, 2020; Sockalingam, Leung, & Cassin, 2020). An epidemiological survey by Waledzick and colleagues showed that nearly 75% of bariatric respondents (including pre-operative and post-operative patients) reported increased anxiety levels due to pandemic uncertainty (Waledziak et al., 2020). Further, approximately 30% of respondents in this survey reported weight gain during COVID-19, with pre-surgery patients reporting weight gain more often than patients after bariatric surgery.

Further complicating the impact of COVID-19 on bariatric surgery outcomes is the relationship between COVID-19 and problematic eating behaviours. Eating psychopathology following bariatric surgery has been linked to poorer long-term outcomes, including weight regain and deteriorations in mental health-related quality of life post-surgery (Shakory et al., 2015; Taube-Schiff et al., 2015; Devlin, King, Kalarchian, White, Marcus, & Garcia, 2016; Youssef et al., 2020). As the pandemic continues, the increased psychosocial distress during quarantine and self-isolation may lead to coping through maladaptive eating behaviors, creating a problematic feedback loop secondary to COVID-19–related distress (Pearl, 2020; Sockalingam et al., 2020). Although the long-term consequences of COVID-19 related distress on obesity care and outcomes remain unclear, authors have purported that virtual care can be utilized to deliver evidence-based psychosocial care to bariatric patients to potentially lessen the effect of COVID-19 related distress on obesity self-management (Sockalingam et al., 2020).

Given the dearth of literature understanding the complex relationship between COVID-19 distress and bariatric surgery outcomes, we conducted a qualitative study to investigate the impact of COVID-19 physical isolation measures during the first wave of this pandemic on bariatric patients coping and self-management post-surgery.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited from the Toronto Bariatric Surgery Psychosocial (Bari-PSYCH) cohort study, an ongoing longitudinal prospective study at the University Health Network-Bariatric Surgery Program (UHN-BSP), formerly named Toronto Western Hospital-Bariatric Surgery Program (Nasirzadeh et al., 2018; Sockalingam et al., 2017). All bariatric surgery candidates in this program are assessed and followed-up by a multidisciplinary team comprised of nurse practitioners, psychologists, social workers, psychiatrists, dietitians and surgeons. It is worth noting that the follow-up duration for participants in this study ranged between (2–5 years) based on participant's surgery date and individual's need for a follow-up beyond 2-years. The pre-surgery assessment process has been described previously in the literature and patients were followed up to 5 years post-surgery (Pitzul et al., 2014; Sockalingam et al., 2013; Thiara et al., 2018, pp. 1545–7206). The UHN-BSP performs two bariatric surgery procedures, the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy (SG), with the surgeon determining surgical procedure based on surgical and medical indications (e.g. previous abdominal surgeries resulting in extensive adhesions and distorted anatomy).

During the period of March to June 2020, participants were recruited through the program's support group (80%), post-operative telephone visits (5%), and the patient-run Facebook group (15%). This time period corresponded with a period of significant public health restrictions including self-isolation, a pause to elective surgeries including bariatric surgery, and closure of ambulatory bariatric clinics. The UHN-BSP provided ongoing virtual visits by telephone or telemedicine as part of routine care during this study period.

Participants in this cohort study analysis were included if they underwent bariatric surgery between 2014 and 2020 and were between 18 and 65 years old. Participants who expressed interest to participate through email or phone communication were contacted by AY, a senior PhD candidate with qualitative research experience, to determine participant eligibility and provide information about the study. Patients who consented participated in semi-structured interviews. The reported nested-study is part of a larger qualitative analysis examining overall patient experience with self-management post-bariatric surgery. The impact of COVID-19 on bariatric patients self-management emerged as a novel phenomenon and an independent interview guide was designed to explore this specific topic. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at UHN and all participants provided both a written and oral informed consent to participate in this study.

2.2. Data collection

Patients participated in individual, in-depth, semi-structured interviews, lasting approximately 40–60 min in duration. Initial interviews (n = 4) started with convenience sampling and then purposeful sampling, aiming for maximum variation in gender, age, and time since surgery to capture variation in patients' experiences and care needs during this pandemic. The interview used open-ended questions spanning across four domains: patients' demographics, support, physical and mental well-being, and self-management prior to and during the pandemic (see Appendix A). Examining individuals' pre-COVID and current status during the pandemic allowed for a constant comparison of changes in individuals' health status and self-management capacity. Interviews were recorded with participants’ permission and transcribed by an independent professional transcription service.

2.3. Data analysis

A constant comparative approach was used to simultaneously collect and analyze data. Analysis of interview transcripts was iterative and inductively driven, using line-by-line coding, open coding, focused coding, and axial coding, following the grounded theory systematic analysis approach (Charmaz, 2014). This analytical approach informed our purposeful sampling approach and allowed us to compare experiences, views, situations, and contexts from within and across individuals. Through the data collection and analysis process, the researcher AY independently coded the data from an exploratory lens and generated a code book. All codes were verified by SS, principal investigator and psychiatrist at the UHN-BSP. Furthermore, iterative and bi-weekly discussions with research team members (SL, SC, SW, and SS), allowed for triangulation of the data from multiple perspectives to critically appraise and identify overarching themes.

3. Results

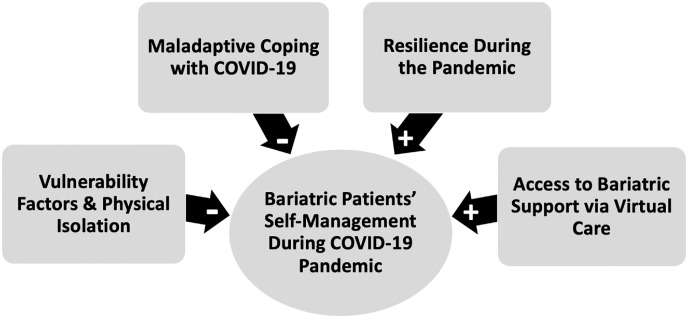

Twenty-three phone interviews were completed between March to June 2020. Of all 23 participants, 19 (82%) were females and 5 (18%) were males. The mean age of this cohort was 50 ± 8.49 years and the mean time since surgery was 2.45 years (range: 6 months - 7 years). Most participants were Caucasian (87%), followed by Arab (9%), and South Asian (4%). Table .1 summarizes study sample characteristics and Table 2 presents individuals’ profile and self-reported concerns related to physical isolation during this pandemic. Qualitative analysis of interview data yielded the following 4 themes: coping with COVID-19; vulnerability factors and physical isolation; resiliency factors during pandemic; and valuing access to support by virtual care as a cross-cutting theme (Fig. 1 ).

Table 1.

Study sample demographic characteristics.

| Sample Characteristics | N (%) orMean ± SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 18 (82%) | ||

| Male | 4 (18%) | ||

| Age (years) | 48.82 ± 10.03 | 37–66 years | |

| Type of Surgery | |||

| Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) | 18 (82%) | ||

| Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) | 4 (18%) | ||

| Surgery Complication | |||

| Yes | 8 (36%) | ||

| No | 14 (64%) | ||

| Post-op (years) | 2.45 ± 1.54 | 6 months - 7 years | |

| Occupation | |||

| Full-time | 15 (65%) | ||

| Retired | 3 (13%) | ||

| Unemployed | 5 (21%) | ||

| Relationship Status | |||

| Married | 9 (39%) | ||

| Single | 9 (39%) | ||

| Divorced | 7 (22%) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 19 (87%) | ||

| Arab | 2 (9%) | ||

| South Asian | 1 (4%) | ||

| Psychiatric Diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 8 (36%) | ||

| No | 15 (65%) | ||

Table 2.

Participants demographic characteristics and self-reported concerns in response to COVID-19 pandemic physical isolation.

| ID | Gender | Age | Type of Surgery | Post-op Year | Relationship Status | Self-Reported Emotional Eating | Physically Active |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 52 | RYGB | 1.5 | M | ✓ | N |

| 2 | F | 43 | RYGB | 2.5 | S | Y | |

| 3 | F | 55 | RYGB | 3.5 | M | N | |

| 4 | F | 42 | SG | 2 | S | N | |

| 5 | F | 42 | RYGB | 1.5 | S | ✓ | N |

| 6 | F | 58 | RYGB | 1.5 | S | N | |

| 7 | F | 47 | RYGB | 5 | S | ✓ | N |

| 8 | F | 65 | RYGB | 5 | S | ✓ | N |

| 9 | F | 52 | RYGB | 9 months | S | ✓ | N |

| 10 | F | 48 | RYGB | 9months | D | N | |

| 11 | M | 65 | SG | 6 months | M | N | |

| 12 | F | 42 | RYGB | 3 | D | ✓ | N |

| 13 | F | 42 | RYGB | 2 | M | Y | |

| 14 | M | 37 | SG | 3 | M | Y | |

| 15 | M | 42 | SG | 9 months | M | Y | |

| 16 | M | 42 | RYGB | 3.5 | M | Y | |

| 17 | F | 48 | RYGB | 4 | M | ✓ | N |

| 18 | F | 66 | RYGB | 7 | S | ✓ | N |

| 19 | F | 55 | RYGB | 4 | D | ✓ | N |

| 21 | F | 57 | RYGB | 4 | M | Y | |

| 22 | F | 47 | RYGB | 9 months | D | ✓ | N |

| 23 | F | 23 | RYGB | 2 | S | ✓ | Y |

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG); Roux-en-Y gastric bypass(RYGB); Married(M), Single(S), Divorced(D); No(N), Yes(Y).

Fig. 1.

This diagram illustrates the various factors influencing bariatric patients' self-management during COVID-19.

3.1. Theme 1: coping with COVID-19

COVID-19 caused significant disruption in patients’ everyday life. Participants reported that stay-at-home, public health orders, changes in daily routine, and the pandemic uncertainty were major contributors to psychosocial distress. Trying to cope with this distress, participants described finding themselves in a “weird mindset” engaging in new behaviours, such as unusual shopping behaviours (e.g., buying a big bag of chips) and experiencing emotional eating habits. Notably, while some participants described coping through maladaptive behaviours, other participants tried to seek positive strategies, such as being more physically active, avoiding triggering foods, baking as a soothing tactile activity, and reviewing mindful eating strategies to mitigate problematic eating behaviours, specifically emotional eating and grazing behaviours (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Themes describing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bariatric patients self-management.

| Themes | Codes | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Engaging in emotional eating | P5: “I have found myself in particular, I have found myself emotionally eating, which is what I used to do. But I'm aware of it. It's not that I've been eating terrible food, but maybe I'm not spacing my food out as best as I could. Maybe I'm not hydrating as much as I could. So, I'm aware of that. This current global situation I think may be causing challenges that I may not have had otherwise.” (F, 1.5-years) P20: “I think, definitely, boredom triggers it. If I make myself busy, which … I can tell you all the right things. It's doing them that's the … if I'm busy, it doesn't matter what the busy is, I definitely don't. I am more sort of … I eat regular meals at regular times, as opposed to that constant grazing. And I know, then, because you can actually eat more if you are grazing, and it usually ends up being … it's not … I don't like sweets. I don't have a sweet tooth. But it'll be even things like nuts. Sure, they are protein, but they are also really high calorie. I eat more of those kinds of snacky foods.” (F, 1-year) P8: “Ask me when the last time was I made an apple pie. Again, three years ago maybe. So, I was making an apple pie. I was literally kneading pastry. They said that this thing about people baking is that it’s a tactile thing, that people are so longing to touch, and they can't, that they have gone into this thing. It's why people are making bread. It's the run on the flour and all that in the store, is just because baking is very soothing, it reminds them of their childhoods, whatever. It's all of that sort of stuff. So, I think that people's relationships with food is really complicated, and especially if you're someone who has had a problem with obesity” (F, 4-years) P20: “When COVID hit, I didn't go shopping for at least the first month, and then it was another month after that, I think, I had to go to Costco because I ran out of all my vitamins. It was just a very stressful experience just because of what is going on with COVID and the masks and the people up in your face. It was a completely, spontaneous, emotion-driven, “I have to have those Doritos.” Everything else in my basket was healthy, but it was just that one thing. That will happen occasionally”. (F, 1-year) |

|

| Engaging in “end-of-world” eating | P8: “I found that the last little while in the whole COVID situation, I thought …. if this is the apocalypse, I might as well enjoy myself. I might as well eat the cupcake. It was like, what's the point? But now seven or eight weeks into this, reality dawns and you feel like doing what we're supposed to do, whatever, we're not going to get sick, there's a really low probability of getting ill. So, you have to get yourself healthy, and that means getting more of that weight off.” (F, 4-years) P8: “We were doing all their shopping …. our neighbour down the street, really athletic woman, we said, we're going shopping, was there anything she wanted. I want a big bag of chips. And I thought she was joking. And I said, yeah, yeah. And she said, no, I want a big bag of chips. And I went, okay. And then we both sort of looked at each other in the store and went, well, if Name-X is getting a big bag of chips, we need a big bag of chips. So, there has been this weird mindset” (F, 4-years) P20: “I found shopping during COVID very stressful and ended up eating chips that I shouldn't have eaten, things like that.” (F, 1-year) |

|

| Finding positive self-coping strategies during isolation | P1: “I'm crocheting a blanket now because I figure if my hands are busy, I'm not going to be eating.” (F, 1-year) P13: I think I very often just need to refocus. I think about the Mindful Eating and what I need to do. I think about how I have to get back on track. Even though I don't go to the gym now, I workout at home. I bought a bunch of weights, I workout at home and I do a lot of programs. And I still speak to a lot of people within the fitness community and we figure out other things. (F, 2.5-years) P17: “I've been taking up crocheting. I used to crochet back in the day. I took up crocheting. I read a little bit. I watch TV. So, that's my time and that's how I've been really winding down at the end of the night. That's what I usually do.” (F, 4-years) P20: “Normally, I avoid buying it. It's the type of thing that if I have it in my home, it calls to me” (F, 1-year) |

|

| Coping with the pandemic uncertainty | P5: “Nobody knows what the timeframe is going to be around COVID and what that's going to mean. I would say that for patients who have had surgery and have been caught in this unfortunate situation. COVID hit right before my 1-year anniversary, which is a critical time.” (F, 1.5-years) P6: “I was struggling with getting the rest of the weight off, so the nutritionist said she would see me again in June. But, I'm not sure what will happen now.” (F, 1.5-years) P23: “We've all joked about the COVID-15 that we put on. I think everybody joked about it, but it's serious. Definitely, for someone like me in this program, that's a big deal to put that weight on. It's not as easy for us just to take that weight off.” (F, 2-years) P5: “Let's say every bariatric patient, as every person in the world, is going through a difficult time right now for different reasons. For people who struggle with their mental health, and many people struggled with their mental health even before the surgery, this is also a form of trauma, this is also a trigger, this pandemic.” (F, 1-year ) |

|

| Triggering Factors Related to Social-Isolation | Fearing food insecurity | P8: “I'm coping but in bad ways. Do you know what I mean? I found that a lot of the issue is around food itself and food insecurities and going into stores and seeing empty shelves has triggered something in me that's almost primal. So, consequently, if I go into a store and I've been telling Name-X this too that we're buying things that we haven't bought in years for fear that we won't be able to buy them.” (F, 4-years) |

| Losing daily lifestyle routine | P13: “I do a lot more grazing. Now with COVID-19, the whole pandemic, meal prepping is definitely difficult. I don't work, so it's easy for me to go into the fridge, anytime. So, I have to really be a little bit more stringent and prep my meals. I don't anymore” (F, 4-years) P13:” It's been very tough. Yeah, my gym isn't open anymore and I used to go to the gym every single day, for 2 h every morning. It's not open and it was very tough when that changed. It put me off. I think that once I do my exercise in the morning, I feel better during the day. I have my routine in the morning, and I eat better during the day. Since that change, it's been very tough. (F, 2.5-years) P18: “Definitely, definitely, definitely because you're home all the time. You're eating all your meals at home. You're munching at home. It's a stressful situation. It's a pandemic, the nature of which we've never been through in our lifetime, and what the hell? What's going on?” (F, 7-years) P23: “I think when you're getting into a new routine that is a new lifestyle, slipping back into older habits can be detrimental to your mental health and to your physical well-being. So, certainly, I think I indulged in it for a little while because I was not feeling well, and I was sick for those 30 days that I was in quarantine and just needed to rest. There was boredom, and there was all sorts of stuff that just leads to snacking” (F, 2-years) |

|

| Losing work/life balance | P12: “Well, I don't know how to explain, my workload is just insane. I'm in conference calls eight to 9 h a day so it's hard for me. Before you would leave work, and sometimes you don't get to your laptop at home, so you have that free time. Now I don't have that work/life balance. I'm always on my laptop, and I find it difficult to cook, especially the weeks I don't have the kids. I'll eat something, like, toast or a bar, a protein bar. I don't know how to explain, but I just can't find the words” (F, 3-years) | |

| Struggling with self-isolation | P17: The fact that I can't go out, that I'm confined to my house. And then when I do have to go out, it's basically to go do grocery shopping. I don't just go out leisurely like I used to. Some weekends I would feel like, let me just go browse in the mall and that type of thing. I would not do that today. Any time I leave the house it's for necessities. So, I find that's very challenging and very frustrating. And we're confined in a condominium” (F, 4-years) P18: “I'm finding it very difficult to work from home. I'm not really fond of that because I like the social interaction. I'm on my own so it's rather isolating” (F, 7-years) P19: “After moving to Toronto and working and then getting sick, I would say for the last four years I have not worked. So, I don't have a lot of friends and people here locally that I can count on. And with my condition, I couldn't go outside, so I had to have somebody to get me my groceries and stuff like that. So, that's again another aspect of depression, which has nothing to do with the sickness at all. That's how COVID has given me a whole different depression and I think that's when I got to the lowest point of everything is during the COVID.” (F, 4-years) |

|

| Valuing Access to Support by Virtual Care | Accessing Bariatric Care During the Pandemic | P19: “Yes accessing bariatric care during this time has been good. You would have people encouraging you, okay, try and get some exercise done, give you alternatives. Well, people can still think of their own. Do an alternative, make sure you do some steps in, do something. Make sure, now that you're not being as active, maybe you want to look at your nutrition, eat differently. It would have been good.” (F, 9-months) P22: “I would say that the webinars that are now online are great. I was having trouble getting to Toronto for the support group because of the time of the day was too early for me to get there, so I wasn't going. But having them online, that is great, I think, if we have those now online. Because then I can go, and I can have the reinforcement.” (F, 5-years) P9: “I had a phone appointment with the bariatric clinic. The [psychiatrist] was able to reduce my anxiety and panic attacks by giving me medication, it was taking a while for the community psychiatrist. I've been on a waiting list for them to call me. So, I was able to call the social worker who put me in touch with the psychiatrist at the program, and they [the bariatric team] got me on the proper medication to help me start feeling better.” (F, 9-months) P8: “A little bit of everything. She's [psychologist] not a nutritionist, so it's not about the nutrition part so much. It's about setting goals and understanding what's happening, both with me and the world, that it’s not just me. There are a lot of people that this is going on for. And helping me work through my thoughts about how I feel about it. I think everyone when they've regained some of the weight, you just feel like a failure.” (F, 4-years) P7: “It's not necessarily just about the food, applying more of an emotional and mental kind of help over things that I have difficulties with. It was just so out of control when I did eat a lot. I think just in general to have support, like emotionally, for weight is really important.” (F, 5-years) |

| Factors Promoting Resiliency | Maintaining daily routine and self-managing well-being | P16: “I would say it was fine, prior to the COVID-19, I was actually working from home all the time. I only went to the office anywhere from two to three days of the month. There was not much of a change in my schedule from working from home. Aside from that I don't know if social distancing changed my lifestyle.” (M, 3.5-years) P14: “Honestly, it did not impact anything at all for me. I'm extremely introverted anyways. I'm not a super social person and I don't go out a lot. So, on both the psychological and the nutritional level, it really didn't impact me that much. …. . So, instead of losing roughly 4 kg every month when I would start being active, I only lost 1.5 kg or something. So, of course, it did slow down the process of me getting healthy again or losing the weight again. But it did not eliminate it. So, I still lost weight, but it's just much lower than typically the past three years.” (M, 3-years) P15: In my personal case, COVID-19 has not impacted me at all, partially because I have got a gym in my basement. I didn't have to suffer because all the gyms and the fitness centres were closed. People suffer to not exercise. In that term, I didn't have that problem. In terms of food, I maintained the very same program as before this COVID situation. I would say I got extremely minimally impacted based on my lifestyle. I'm not talking about the work, and working from home and stuff, but if we talk about only the program related to the post-surgery, it's almost no impact to me. (M, 9-months) |

| Financial security | P6: “I'm adapting and coping … At least I'm getting my pension every month, regardless. I don't have to worry about getting paid. Even when I worked, if I was still working, if I wasn't retired, I would still be getting my paycheque, whether I was working from home or not working. That's huge for a lot of people.” (F, 1.5-years) P5: “If you lose your income, if you lose the ability to go to the gym and be active, if you lose the ability to be able to buy the foods that you need to eat that keep you on track, it's hugely disruptive.” (F, 1.5-years) |

3.2. Engaging in emotional eating behaviours

Participants described engaging in emotional eating as a way to cope with feelings of anxiety or boredom triggered by the pandemic scale and uncertainty. Importantly, despite increased emotional eating during the pandemic, patients described an increased awareness of types of food, quantity, and hunger cues.

P5: “I have found myself in particular emotionally eating, which is what I used to do. But I'm aware of it. It's not that I've been eating terrible food, but maybe I'm not spacing my food out as best as I could. Maybe I'm not hydrating as much as I could. So, I'm aware of that. This current global situation I think may be causing challenges that I may not have had otherwise.” (F, 1.5-years)

3.3. Developing positive self-coping strategies

All participants highlighted the tendency to cope in maladaptive ways during distress. Some participants described developing positive strategies to mitigate the COVID-19 related distress. For example, participants (2-years or more post-surgery) described trying to be more self-conscious of their emotions and engaged in virtual community programs to maintain their daily lifestyle routine.

P13: “I think I very often just need to refocus. I think about the Mindful Eating and what I need to do. I think about how I have to get back on track. Even though I don't go to the gym now, I workout at home. I bought a bunch of weights, I workout at home and I do a lot of programs. And I still speak to a lot of people within the fitness community and we figure out other things.” (F, 2.5-years)

3.4. Engaging in end-of-World eating

During the peak period of the pandemic, some participants described COVID-19 as a life-ending “apocalypse” and therefore, engaged in eating habits that provided momentary pleasure.

P8: “I found that the last little while in the whole COVID situation, I thought …. if this is the apocalypse, I might as well enjoy myself. I might as well eat the cupcake. It was like, what's the point? But now seven or eight weeks into this, reality dawns and you feel like doing what we're supposed to do, whatever, we're not going to get sick, there's a really low probability of getting ill. So, you have to get yourself healthy, and that means getting more of that weight off.” (F, 4-years)

3.5. Dealing with pandemic uncertainty

Participants in their early post-operative period (6 months–2 years) described having feelings of anxiety, fearing how the pandemic might impact their follow-up appointments and accessing bariatric care if needed. In particular, participants with co-existing mental illness or with poor weight loss outcomes were more likely to be worried and concerned about the impact of this pandemic on their surgery long-term outcomes.

P5: “Nobody knows what the timeframe is going to be around COVID and what that's going to mean. I would say that for patients who have had surgery and have been caught in this unfortunate situation. COVID hit right before my 1-year anniversary, which is a critical time.” (F, 1.5-years)

P6: “I was struggling with getting the rest of the weight off, so the nutritionist said she would see me again in June. But, I'm not sure what will happen now.” (F, 1.5-years)

3.6. Theme 2: vulnerability factors and physical isolation

Patients reported significant disruptions to their daily lifestyle routine as a result of stay-at-home orders, triggered by fears of food insecurity, sedentary lifestyle, and feelings of social isolation. Bariatric patients perceived these triggering factors to create a stressful environment that made it more difficult to adhere to the recommended dietary guidelines and to self-manage their physical and mental well-being during quarantine (Table 3).

Participants perceived shopping during the pandemic to be very stressful. While some reported fearing availability of particular food types, others perceived their food insecurity to be triggered by the lack of food supplies and panic-buying environment.

P8: “I'm coping but in bad ways. Do you know what I mean? I found that a lot of the issue around food itself and food insecurities and going into stores and seeing empty shelves has triggered something in me that's almost primal. So, consequently, if I go into a store and I've been telling Name-X this too that we're buying things that we haven't bought in years for fear that we won't be able to buy them.” (F, 4-years)

3.7. Losing daily lifestyle routine

Participants perceived maintaining their daily routine to be critical for successful self-management. Following their daily routine often resulted in meal regularity, improved food choice, and helped control grazing.

P13: “I do a lot more grazing. Now with COVID-19, the whole pandemic, meal prepping is definitely difficult. I don't work, so it's easy for me to go into the fridge, anytime. So, I have to really be a little bit more stringent and prep what foods I use to make containers. I don't anymore” (F, 4-years)

3.8. Losing work/life balance

Participants described working from home during the pandemic to be mentally stressful and exhausting. They reported an increased distress due to lack of physical interactions with co-workers, increased workload, and working from home to have influenced their eating habits with respect to meal regularity and preparation.

P12:” Well, I don't know how to explain, my workload is just insane. I'm in conference calls eight to 9 h a day so it's hard for me. Before you would leave work, and sometimes you don't get to your laptop at home, so you have that free time. Now I don't have that work/life balance. I'm always on my laptop, and I find it difficult to cook. I'll eat something, like, toast or a bar, a protein bar. I don't know how to explain, but I just can't find the words.” (F, 3-years)

3.9. Lacking social support and struggling with self-isolation

Participants described feeling confined, isolated, frustrated, and being at their lowest point emotionally due to limited social interactions. Participants perceived home confinement created a challenging environment for individuals struggling with emotional eating and/or depression.

P19: “I don't have a lot of friends and people here locally that I can count on. And with my condition, I couldn't go outside, so I had to have somebody to get me my groceries and stuff like that. So, that's again another aspect of depression, which has nothing to do with the sickness at all. That's how COVID has given me a whole different depression and I think that's when I got to the lowest point of everything is during the COVID.” (F, 4-years)

P18: “I'm finding it very difficult to work from home. I'm not really fond of that because I like the social interaction. I'm on my own so it's rather isolating” (F, 5 years).

3.10. Theme 3: Resilience during the pandemic

Some participants perceived quarantine as a minimal burden with respect to maintaining their lifestyle and self-management. These patients reported being able to maintain social support and connection virtually and to adhere to regular routines and maintain lifestyle changes despite the disruptions of the pandemic. Exploring factors promoting successful self-management, participants reported a greater sense of financial security, felt well-supported, and did not have any pre-existing mental health conditions. Importantly, these individuals were more likely to be males and to be married (Table 3).

P14: “Honestly, it did not impact anything at all for me. I'm extremely introverted anyways. I'm not a super social person and I don't go out a lot. So, on both the psychological and the nutritional level, it really didn't impact me that much. …. . So, instead of losing roughly 4 kg every month when I would start being active, I only lost 1.5 kg or something. So, of course, it did slow down the process of me getting healthy again or losing the weight again. But it did not eliminate it. So, I still lost weight, but it's just much lower than typically the past three years.” (M, 3-years)

P15: “In my personal case, COVID-19 has not impacted me at all, partially because I have got a gym in my basement. I didn't have to suffer because all the gyms and the fitness centres were closed. People suffer to not exercise. In that term, I didn't have that problem. In terms of food, I maintained the very same program as before this COVID situation. I would say I got extremely minimally impacted based on my lifestyle. I'm not talking about the work, and working from home and stuff, but if we talk about only the program related to the post-surgery, it's almost no impact to me.” (M, 9-months)

3.11. Theme 4: valuing access to support by virtual care [cross-cutting theme]

Participants described how accessing bariatric support through virtual care during the pandemic helped boost their self-efficacy, set realistic behavioral goals, and reinforced mindful eating strategies to combat emotional eating or grazing (Table 3).

P9: “I had a phone appointment with the bariatric clinic. The [psychiatrist] was able to reduce my anxiety and panic attacks by giving me medication, it was taking a while for the community psychiatrist. I've been on a waiting list for them to call me. So, I was able to call the social worker who put me in touch with the psychiatrist at the program, and the bariatric team got me on the proper medication to help me start feeling better.” (F, 9-months)

P7: “I guess it's more so that I have certain thought patterns and feelings and ways of doing things and then at the end we also go over my weight and eating stuff. It's very, very helpful.” (F, 5-years)

In addition to individual virtual appointments, patients valued accessing online support groups as a way to stay socially connected, seek advice from peers and healthcare professionals, and better self-manage their health and well-being during the uncertainty of COVID-19. Virtual support groups were a “constant refresher” and an opportunity to share and learn coping strategies from others with similar concerns. Virtual support groups promoted resiliency, reduced feelings of self-isolation and promoted access to experts’ advice.

P19: “Yes accessing bariatric care during this time has been good. You would have people encouraging you, okay, try and get some exercise done, give you alternatives. Well, people can still think of their own. Do an alternative, make sure you do some steps in, do something. Make sure, now that you're not being as active, maybe you want to look at your nutrition, eat differently. It would have been good.” (F, 9-months)

4. Discussion

The current COVID-19 pandemic has caused significant disruption in individuals' daily lives and increased psychosocial distress on a global scale. Compared to the general population, individuals with obesity are more vulnerable to infection, sedentary lifestyle, and experiencing significant mental health distress (Kassir, 2020). Although a number of editorials have highlighted the increased risk in psychosocial distress secondary to the stay-at-home orders and changes in daily lifestyle routines (Mattioli et al., 2020; Pearl, 2020; Sockalingam et al., 2020), this qualitative study is the first to describe the impact of COVID-19 on post-operative bariatric patients' self-management. In particular, exploring the perspective of a diverse sample of bariatric patients ranging from early post-surgery (i.e. 6-months post-surgery) to several years post-surgery (i.e. 7-years post-surgery) provided novel insights into the impact of COVID-19 on obesity self-management and individuals’ care needs relative to the patient's follow-up stage.

Four main themes highlighted the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bariatric patients' self-management post-surgery. These themes included: coping with COVID-19, vulnerability factors and physical isolation, resiliency factors during pandemic, and valuing access to bariatric support by virtual care. Overall, participants thought the pandemic resulted in enormous mental health distress requiring them to find strategies to cope with this evolving pandemic situation. Differences in participants' coping strategies, specifically their use of maladaptive versus adaptive approaches, were accounted for in part by individuals’ unique challenges and their self-reported complex relationship with food. For example, while some patients found baking to be soothing and a means of staying connected, others found cooking and being self-isolated at home to be a triggering environment for emotional eating and grazing.

Furthermore, the psychosocial distress secondary to COVID-19 impacted participants’ obesity self-management capabilities disproportionally. Some participants described being confused and ambivalent about their shopping behaviours during the pandemic, buying large amounts and unnecessary items due to fears of food insecurity. Others described feeling at their “lowest point” due to being confined in their home and feeling socially isolated. Interestingly, participants with co-existing mental illness (30% of the sample) who had continued access to bariatric support through virtual care during the pandemic found that connecting with their bariatric care team was extremely helpful in managing their eating habits, being cognitively aware of their emotional status, and developing self-compassion and acceptance of their reactions to this unprecedented situation. This support was important to participants because it not only boosted their self-efficacy to self-manage their eating behaviours but also instilled in patients the motivation to maintain their daily routine during the pandemic.

Notably, there maybe a gender-specific response to psychosocial distress. In this study, women were more likely to use food to cope with stress, whereas men were more likely to have had better self-control or have coped through other strategies. This finding is consistent with the existing literature on alcohol use trends during COVID-19, which showed that women were more likely to consume larger amounts of alcohol due to stress, while men consumed more alcohol due to boredom during COVID-19 (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2020). In addition, the theme of self-managing physical and mental well-being appeared to be influenced by health inequities. Participants who reported feeling “minimal impact” of COVD-19 on their health and lifestyle were more likely to have “financial security”, space and equipment at home to stay physically active, and adequate emotional support. This theme further underscores the association between health inequities and the increased levels of psychosocial distress, negatively impacting individual's ability to maintain their healthy lifestyle during times of uncertainty.

Overall, findings from this study with respect to increased psychosocial distress in bariatric patients align with epidemiological findings by Waledzick and colleagues where approximately 75% (n = 800) of survey respondents indicated increased level of anxiety concerning their health and 20% attributed their increased anxiety to limited access to bariatric care during the pandemic (Waledziak et al., 2020). Our results also support studies on changes in eating habits and changes in daily routine due to stay-at-home orders (Mattioli et al., 2020; Mitchell, Behr, Deluca, & Schaffer, 2020; Pearl, 2020). Importantly, this qualitative study is the first to provide insights to experiences and care needs of post-surgery bariatric patients who may be susceptible to maladaptive coping mechanisms during times of uncertainty. Findings from this study underscore the importance of time to follow-up after bariatric surgery on patients’ self-reported concerns during physical isolation. For example, participants who had their bariatric surgery completed within 1-year, were less likely to report concerns including emotional eating and fear of weight regain as they were still within their peak weight loss period and perceived higher levels of self-regulation due to the physical control of the surgery (Table .1). An important implication of this study is underscoring the potential of virtual care to promote access to bariatric care and support to deliver evidence-based treatments that enable patients to mitigate distress and set realistic behavioural goals that support eating lifestyle and emotions self-management during isolation (Hussain et al., 2020).

The main strength of this qualitative study is capturing a detailed account of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on bariatric patients’ post-surgical experiences coping and self-managing their physical and mental well-being during this pandemic. This study included both male and female participants, therefore allowing to examine gender-specific response. A possible limitation to this study is the lack of ethnic diversity due to the small sample size and limitations to recruitment during the pandemic. Although our sample size (n = 23) was relatively small, we adopted a rigorous qualitative analysis approach: independently coding the data, iterative research team discussions, and validating emerging themes with a number of participants. Theoretical saturation was achieved through our sampling methods with over 18 h of interview data and 500 pages of transcripts for our analysis.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated the impact of COVID-19 on bariatric patients' post-operative self-management during quarantine or self-isolation. Findings from this study revealed that the increased mental health distress secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted individuals’ capacity for bariatric self-management during quarantine. As a result, patients had to develop new coping strategies to mitigate COVID-19 related distress. While some were able to find positive coping strategies to stay connected and maintain their daily lifestyle routine, majority of participants reported coping in maladaptive ways. Moreover, findings from this study bolster the importance of leveraging virtual care to maintain access to obesity care during COVID-19 restrictions and to provide personalized support to mitigate the long-term unintended consequences of this pandemic.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the Medical Psychiatry Alliance (MPA). MPA is a collaborative health partnership of the University of Toronto, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Hospital for Sick Children, Trillium Health Partners, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, and an anonymous donor. This project was also supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant (CIHR) [#376045].

Declaration of competing interest

None to Declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105166.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction . 2020. Boredom and stress drives increased alcohol consumption during COVID-19: NANOS poll summary report. Canadian Centre On Substance Use And Addiction. [online].Ccsa.ca. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. 2nd ed. SAGE; London: 2014. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin Michael J., King Wendy C., Kalarchian Melissa A., White Gretchen E., Marcus Marsha D., Garcia Luis, et al. Eating pathology and experience and weight loss in a prospective study of bariatric surgery patients: 3-year follow-up. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2016;49(12):1058–1067. doi: 10.1002/eat.22578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S., Merchant R.M., Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanemi A., Yoshioka M., St-Amand J. Will an obesity pandemic replace the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic? Medical Hypotheses. 2020;144:110042. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain A., Mahawar K., El-Hasani S. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on obesity and bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2020;30(8):3222–3223. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04637-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassir R. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with obesity. Obesity Reviews. 2020;21(6) doi: 10.1111/obr.13034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manderson L., Levine S. COVID-19, risk, fear, and fall-out. Medical Anthropology. 2020;39(5):367–370. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2020.1746301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli A.V., Pinti M., Farinetti A., Nasi M. Obesity risk during collective quarantine for the COVID-19 epidemic. Obesity Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.obmed.2020.100263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell E., Yang Q., Behr H., Deluca L., Schaffer P. Self-reported food choices before and during COVID-19 lockdown. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.15.20131888.this. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasirzadeh Y., Kantarovich K., Wnuk S., Okrainec A., Cassin S.E., Hawa R., et al. Binge eating, loss of control over eating, emotional eating, and night eating after bariatric surgery: Results from the Toronto bari-PSYCH cohort study. Obesity Surgery. 2018;28(7):2032–2039. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl R.L. Weight stigma and the "Quarantine-15. Obesity. 2020;28(7):1180–1181. doi: 10.1002/oby.22850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl R.L. Weight Stigma and the “Quarantine‐15”. Obesity. 2020;28:1180–1181. doi: 10.1002/oby.22850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzul K.B., Jackson T., Crawford S., Kwong J.C.H., Sockalingam S., Hawa R.…Okrainec A. Understanding disposition after referral for bariatric surgery: When and why patients referred do not undergo surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2014;24(1):134–140. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettie H., Daniels J. Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist. 2020 doi: 10.1037/amp0000710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakory S., Van Exan J., Mills J.S., Sockalingam S., Keating L., Taube-Schiff M. Binge eating in bariatric surgery candidates: The role of insecure attachment and emotion regulation. Appetite. 2015;91:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockalingam S., Cassin S., Crawford S.A., Pitzul K., Khan A., Hawa R.…Okrainec A. Psychiatric predictors of surgery non-completion following suitability assessment for bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2013;23(2):205–211. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0762-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockalingam S., Hawa R., Wnuk S., Santiago V., Kowgier M., Jackson T.…Cassin S. Psychosocial predictors of quality of life and weight loss two years after bariatric surgery: Results from the Toronto Bari-PSYCH study. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2017;47:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockalingam S., Leung S.E., Cassin S.E. The impact of COVID-19 on bariatric surgery: Re-defining psychosocial care. Obesity. 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . 2020. Canadians' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Taube-Schiff M., Van Exan J., Tanaka R., Wnuk S., Hawa R., Sockalingam S. Attachment style and emotional eating in bariatric surgery candidates: The mediating role of difficulties in emotion regulation. Eating Behaviors. 2015;18:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiara G., Yanofksy R., Abdul-Kader S., Santiago V.A., Cassin S., Okrainec A.…Sockalingam S. 2018. Toronto bariatric interprofessional psychosocial assessment suitability scale: Evaluating A new clinical assessment tool for bariatric surgery candidates. ((Electronic))) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsamakis K., Triantafyllis A.S., Tsiptsios D., Spartalis E., Mueller C., Tsamakis C.…Rizos E. COVID-19 related stress exacerbates common physical and mental pathologies and affects treatment (Review) Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(1):159–162. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waledziak M., Rozanska-Waledziak A., Pedziwiatr M., Szeliga J., ProczkoStepaniak M., Wysocki M.…Major P. Bariatric surgery during COVID-19 pandemic from patients' point of view-the results of a national survey. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;9(6) doi: 10.3390/jcm9061697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef A., Keown-Stoneman C., Maunder R., Wnuk S., Wiljer D., Mylopoulos M., et al. Surgery for obesity and related diseases. 2020. Differences in physical and mental health-related quality of life outcomes 3 years after bariatric surgery: A group-based trajectory analysis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.