Abstract

Background

The Daily-PROactive and Clinical visit-PROactive Physical Activity (D-PPAC and C-PPAC) instruments in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) combines questionnaire with activity monitor data to measure patients’ experience of physical activity. Their amount, difficulty and total scores range from 0 (worst) to 100 (best) but require further psychometric evaluation.

Objective

To test reliability, validity and responsiveness, and to define minimal important difference (MID), of the D-PPAC and C-PPAC instruments, in a large population of patients with stable COPD from diverse severities, settings and countries.

Methods

We used data from seven randomised controlled trials to evaluate D-PPAC and C-PPAC internal consistency and construct validity by sex, age groups, COPD severity, country and language as well as responsiveness to interventions, ability to detect change and MID.

Results

We included 1324 patients (mean (SD) age 66 (8) years, forced expiratory volume in 1 s 55 (17)% predicted). Scores covered almost the full range from 0 to 100, showed strong internal consistency after stratification and correlated as a priori hypothesised with dyspnoea, health-related quality of life and exercise capacity. Difficulty scores improved after pharmacological treatment and pulmonary rehabilitation, while amount scores improved after behavioural physical activity interventions. All scores were responsive to changes in self-reported physical activity experience (both worsening and improvement) and to the occurrence of COPD exacerbations during follow-up. The MID was estimated to 6 for amount and difficulty scores and 4 for total score.

Conclusions

The D-PPAC and C-PPAC instruments are reliable and valid across diverse COPD populations and responsive to pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions and changes in clinically relevant variables.

Keywords: COPD epidemiology, exercise

Key messages.

What is the key question?

What is the validity and responsiveness of the Daily-PROactive and Clinical visit-PROactive Physical Activity (D-PPAC and C-PPAC) instruments in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)?

What is the bottom line?

The D-PPAC and C-PPAC instruments, combining questionnaire with activity monitor data, are reliable and valid across diverse COPD populations and responsive to drug and non-drug interventions.

Why read on?

This study combined more than 1300 patients from seven randomised controlled trials, covering a range of countries, languages, COPD disease severities, ages, objective physical activity levels and clinical determinants, wider than what is usually seen in other questionnaire/patient-reported outcome development programmes.

Introduction

Research has consistently shown that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have lower physical activity levels than their healthy peers,1 that reduced physical activity predicts both exacerbations and mortality,2 and that many patients limit their physical activity to avoid symptoms.3 Hence, understanding physical activity is a key to improve the prognosis in patients with COPD.

Physical activity in COPD has been mostly assessed in terms of frequency, intensity, time and type4 and quantified by means of activity monitors or questionnaires.5 Other instruments have focused on quantifying the symptoms or quality of life in relation to physical activities.6 7 However, the patients’ experience of physical activity has been ignored despite patients with COPD typically describe an inability to complete the activities they enjoy because of their illness8 and report that treatments that improve physical activity are of value to them.9 Until recently, no valid measurement tools have been available to capture the experience of physical activity. In the framework of the European Union Innovative Medicines Initiative PROactive project, the PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instruments (Daily and Clinical visit versions, D-PPAC and C-PPAC) were developed following the recommendations of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance.10 In contrast with previous research, results of the development phase of PPAC instruments clearly showed that neither questionnaires nor activity monitors alone could discriminate well within the latent patient-centred construct ‘experience of physical activity’, while the combination of both achieved good discrimination at all ranges of the scale.11 In agreement with previous qualitative work,12 the development and initial validation of the PPAC instruments suggested that the concept ‘physical activity experience’ in patients with COPD is structured in two domains: ‘amount of physical activity’ and ‘difficulty with physical activity’. Thus, D-PPAC and C-PPAC combine questionnaire items and activity monitor variables to measure amount of physical activity, difficulty with physical activity and total physical activity experience.

A first validation study showed that both instruments are simple, reliable and valid measures of physical activity experience in COPD.11 However, data on responsiveness (response to interventions and ability to detect change) and minimal important difference (MID), which are necessary for the effective use of PPAC instruments as study outcomes, have not yet been reported. Moreover, reliability and validity of PPAC instruments across different severity stages, countries and languages need to be reported in order to support their widespread use.

This study aimed to confirm the reliability and validity of the PPAC instruments in multiple independent patient samples, to test their responsiveness and to define their MIDs in a large population of patients with varying COPD severity from diverse settings and countries.

Methods

A complete version of methods is available in an online supplemental file.

thoraxjnl-2020-214554supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Study design and subjects

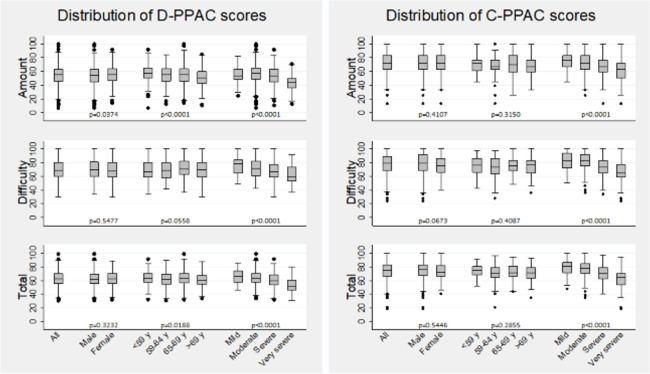

We retrospectively pooled data from seven prospective randomised controlled trials testing the effect of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions in patients with COPD from 17 countries in Europe and North America: the ACTIVATE (Effect of Aclidinium/Formoterol on Lung Hyperinflation, Exercise Capacity and Physical Activity in Moderate to Severe COPD Patients, NCT02424344),13 ATHENS (Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program and PROactive Tool, NCT02437994),14 EXOS (Exercise Outcome Study: a comprehensive comparison of the sensitivity of common exercise outcome measures for COPD, ISRCTN:64759523),15 MrPAPP (Impact of Telecoaching Program on Physical Activity in Patients With COPD, NCT02158065),16 PHYSACTO (Effect of Inhaled Medication Together With Exercise and Activity Training on Exercise Capacity and Daily Activities in Patients With Chronic Lung Disease With Obstruction of Airways, NCT02085161),17 TRIGON-T9 (Efficacy and Safety of Glycopyrrolate Bromide of COPD Patients, NCT02189577)18 and URBAN TRAINING (Effectiveness of an Intervention of Urban Training in Patients With COPD: a Randomised Controlled Trial, NCT01897298)19 studies. Online supplemental table S1 provides details on each trial’s purpose, inclusion and exclusion criteria, design and intervention. Trials contributed differently to the evaluation of different measurement properties depending on when D-PPAC and C-PPAC were measured (figure 1). Briefly, all studies contributed to reliability–internal consistency and validity analyses with their baseline data; TRIGON-T9 contributed to reliability-test–retest analysis with baseline and 14 days data; ACTIVATE (bronchodilator intervention) contributed to responsiveness with baseline and 8 weeks of data; PHYSACTO (bronchodilator with behavioural physical activity intervention), MrPAPP (behavioural physical activity intervention) and ATHENS contributed to responsiveness with baseline and 12 weeks of data and URBAN TRAINING (behavioural physical activity intervention) contributed to the responsiveness analysis with baseline and 12 months of data. All trials recruited patients with stable COPD defined by spirometry (according to the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society criteria)20 and invited all patients to answer one of the PPAC questionnaires (except in MrPAPP that answered both D-PPAC and C-PPAC) and record physical activity data by wearing activity monitors. All trials were registered and approved by appropriate institutional review boards. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Figure 1.

Contribution of each trial to the assessment of measurement properties of Daily-PROactive and Clinical visit-PROactive Physical Activity (D-PPAC and C-PPAC) instruments. ACTIVATE, Effect of Aclidinium/Formoterol on Lung Hyperinflation, Exercise Capacity and Physical Activity in Moderate to Severe patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), NCT02424344; ATHENS, Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program and PROactive Tool, NCT02437994; EXOS, Exercise Outcome Study: a comprehensive comparison of the sensitivity of common exercise outcome measures for COPD, ISRCTN:64759523; MrPAPP, Impact of Telecoaching Program on Physical Activity in patients with COPD, NCT02158065; PHYSACTO, Effect of Inhaled Medication Together with Exercise and Activity Training on Exercise Capacity and Daily Activities in Patients with Chronic Lung Disease With Obstruction of Airways, NCT02085161; TRIGON-T9, Efficacy and Safety of Glycopyrrolate Bromide of patients with COPD, NCT02189577; URBAN TRAINING, Effectiveness of an Intervention of Urban Training in patients with COPD: a randomised controlled trial, NCT01897298.

Measures

D-PPAC and C-PPAC instruments require both questionnaire and activity monitor data. Patients completed D-PPAC and/or C-PPAC questionnaires, which had been previously developed using appropriate qualitative and quantitative research methods and culturally sensitive translations12 and a rigorous item reduction process following current European Medicines Agency (EMA)21 and US FDA10 guidance, as described elsewhere.11 In brief, the D-PPAC questionnaire consists of 7-items with a daily recall and needs to be completed every evening for a week via an electronic-handled device. The C-PPAC questionnaire has 12 items with a 1-week recall and is completed at the day of each study visit in an electronic-handled device, a web-based system or using paper and pen. Patients also wore one of the activity monitors validated to be part of the PPAC instruments (DynaPort MoveMonitor, McRoberts B.V., The Netherlands or Actigraph G3Tx, Actigraph, Pensacola, Florida, USA) during waking time in 1 week at each study visit. Data from individuals were considered valid if they recorded more than 8 hour of wearing time on at least 3 days (not necessarily consecutive) within 1 week. We calculated D-PPAC and C-PPAC scores by combining questionnaire items with two variables from activity monitors (steps/day and vector magnitude units (VMU)/min). Both for D-PPAC and C-PPAC instruments, three scores are generated (amount of physical activity, difficulty with physical activity and total physical activity experience) ranging from 0 to 100, where higher numbers indicate a better score. For the D-PPAC instrument, we obtained scores for each day and calculated a weekly mean of D-PPAC amount, difficulty and total scores. For the C-PPAC instrument, a weekly measure for each score was obtained. D-PPAC and C-PPAC items and scoring equivalences are reported in the online supplemental file.

We also obtained information about: time in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per day (>3 metabolic equivalents, MVPA) from the activity monitor; lung function by spirometry after reversibility testing; exercise capacity by 6 min walking distance (6MWD); the modified Medical Research Council Dyspnoea scale (mMRC), the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ), the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) and/or the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and demographics, smoking history and clinical data (medical and COPD histories) from patients and medical records. Patients participating in follow-up visits also rated the global change of their physical activity experience in amount, difficulty and overall since baseline to follow-up on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from ‘much worse’ to ‘much better’ (see online supplemental file).

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculations and complete statistical analysis are available in the online supplemental file. The analysis sets and statistical analysis plan were defined a priori based on study objectives. We used different study samples for the different measurement properties (figure 1). All analyses were performed separately for D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount, difficulty and total scores.

Reliability was evaluated in terms of internal consistency by the Cronbach’s alpha and test–retest reproducibility, using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and Bland-Altman plots. (Internal consistency of the total scores was not tested because total scores are calculated as the mean of amount and difficulty scores and not from a list of items). Convergent validity was explored by testing the Spearman correlations between D-PPAC and C-PPAC scores and related constructs. A matrix of expected correlations for each variable was built a priori (online supplemental table S2 and Methods (complete version) in online supplemental file). We also tested known-group validity using one-way ANOVA test and pairwise comparisons of means adjusting for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction between groups a priori expected to have differences in physical activity experience. Reliability and validity analyses were done in all patients and stratifying by sex, age groups, COPD severity, country and language.

To quantify responsiveness (response to interventions and ability to detect change), we calculated the change (8 weeks, 12 weeks or 12 months minus baseline) and the standardised response mean (SRM) in (1) each intervention group, using each study separately (a priori expected significant differences (p<0.05) in the changes between groups and SRM>|0.5| in difficulty and total scores after bronchodilator and pulmonary rehabilitation interventions, and in amount and total scores after behavioural physical activity interventions, see online supplemental table S3), (2) groups defined by the self-reported change in physical activity experience, using a pooled dataset (a priori expected significant differences (p<0.05) and SRM>|0.5| in PPAC scores between much worse/worse/slightly worse versus no change/slightly better and better/much better versus no change/slightly better, see online supplemental table S3) and (3) groups defined according to having had COPD exacerbations during follow-up, using a pooled dataset (a priori expected significant differences (p<0.05) and SRM>|0.5| in PPAC scores between those having any COPD exacerbation during follow-up versus none). We established the MID by triangulation using an anchor-based approach22 and calculated distribution-based estimates to provide insight into minimal detectable change (MDC) (not formally established because of scarcity of data for C-PPAC). Analyses were performed using complete cases in STATA V.14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Distribution of D-PPAC and C-PPAC scores

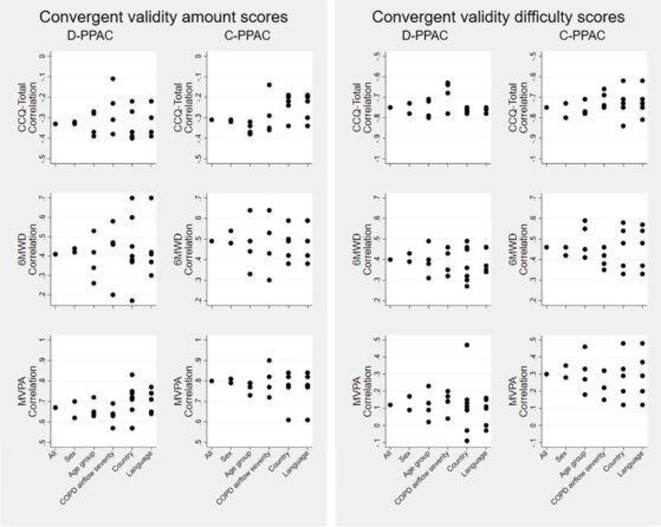

From a total of 1595 patients with stable COPD participating in the original trials, 1324 (83%) had available data on activity monitor and D-PPAC and/or C-PPAC questionnaires. Among them, 950 and 651 patients were included in the D-PPAC and C-PPAC-related analyses, respectively. Baseline characteristics are shown in table 1 (overall) and S4 (stratified by study; of note, differences between samples reflect intentional differences in inclusion/exclusion criteria between studies). Both D-PPAC and C-PPAC samples covered a wide range of COPD severity and objective physical activity levels and included patients from 17 countries completing the PPAC instruments in 11 languages (online supplemental table S5). D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount scores covered the full range between 0 and 100 and were more heterogeneous than difficulty scores (figure 2). There were no patients reporting difficulty scores between 0 and 25 (ie, high difficulty). We observed small significant differences by gender and age group in the amount and total D-PPAC scores but not in any of C-PPAC scores. There was a trend towards lower values of all scores by airflow severity group.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with COPD included in the validation of D-PPAC and C-PPAC instruments

| D-PPAC dataset n=950 |

C-PPAC dataset n=651 |

|||

| n* | m (SD)/n (%) | n* | m (SD)/n (%) | |

| Age (years) | 950 | 64.5 (7.7) | 651 | 67.7 (8.5) |

| Gender: male | 950 | 597 (63) | 651 | 486 (75) |

| Working status: employed | 352 | 48 (14) | 643 | 79 (12) |

| Current smoker | 950 | 394 (41) | 651 | 157 (24) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 950 | 27.0 (5.1) | 651 | 27.3 (5.1) |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 721 | 178 (25) | 593 | 255 (43) |

| Diabetes | 950 | 91 (10) | 593 | 112 (19) |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 720 | 193 (27) | 599 | 95 (16) |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 949 | 54 (17) | 651 | 56 (20) |

| ATS/ERS stages: | 949 | 651 | ||

| I—mild (FEV1 ≥80%) | 55 (6) | 80 (12) | ||

| II—moderate (FEV1 <80% and ≥50%) | 489 (51) | 308 (47) | ||

| III—severe (FEV1 <50% and ≥30% | 339 (36) | 202 (31) | ||

| IV—very severe (FEV1 <30%) | 66 (7) | 61 (10) | ||

| FVC (% predicted) | 949 | 96 (21) | 651 | 84 (21) |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 949 | 48 (12) | 651 | 51 (14) |

| 6MWD (m) | 631 | 446 (102) | 648 | 462 (105) |

| Dyspnoea (mMRC 0–4) | 861 | 1.6 (0.9) | 650 | 1.4 (1.0) |

| Any COPD exacerbations last 12 m | 862 | 268 (31) | 641 | 323 (51) |

| Any COPD exacerbations requiring admissions last 12 m | 633 | 66 (10) | 641 | 82 (13) |

| CRQ dyspnoea (1-7) | 304 | 5.1 (1.4) | 52 | 2.3 (0.7) |

| CRQ fatigue (1-7) | 304 | 4.6 (1.2) | 52 | 1.7 (0.5) |

| CRQ emotional (1-7) | 304 | 5.2 (1.1) | 52 | 3.4 (1.1) |

| CRQ mastery (1-7) | 304 | 5.3 (1.3) | 52 | 2.0 (0.6) |

| CCQ symptoms (0–6) | 328 | 1.9 (1.1) | 597 | 1.7 (1.1) |

| CCQ functional (0–6) | 328 | 1.8 (1.3) | 597 | 1.5 (1.2) |

| CCQ mental (0–6) | 328 | 1.4 (1.4) | 597 | 1.3 (1.4) |

| CCQ total (0–6) | 328 | 1.8 (1.0) | 649 | 1.6 (1.0) |

| CAT (0–40) | 21 | 20 (6) | 365 | 13 (7) |

| Steps per day (n/day) | 950 | 5723 (3768) | 651 | 6500 (4001) |

| VMU/min | 950 | 428 (287) | 651 | 442 (320) |

| Time in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (min/day) | 950 | 89 (51) | 574 | 98 (48) |

| PPAC-amount (0–100) | 950 | 54 (14) | 651 | 70 (16) |

| PPAC-difficulty (0–100) | 950 | 70 (14) | 651 | 78 (15) |

| PPAC-total (0–100) | 950 | 62 (10) | 651 | 74 (12) |

*Some variables have missing values and/or are only available in some studies. Online supplemental table S4 shows patients’ characteristics stratified by study.

ATS/ERS, American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society; BMI, body mass index; CAT, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test; CCQ, clinical chronic obstructive pulmonary disease questionnaire; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; C-PPAC, Clinical visit version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; CRQ, chronic respiratory questionnaire; D-PPAC, Daily version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; IC, inspiratory capacity; mMRC, modified medical research council dyspnoea scale; 6MWD, 6 min walking distance; PPAC, PROactive physical activity in COPD; VMU, vector magnitude unit.

Figure 2.

Distribution of D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount, difficulty and total scores, overall and stratified by gender, age group (quartiles) and COPD airflow severity groups. *p<0.05. Box indicates the lower and upper quartiles, the line subdividing the box represents the median, and lines (whiskers) represent 1.5 IQR of the nearer quartile (lower/upper adjacent values). C-PPAC, Clinical visit version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; D-PPAC, Daily version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument.

Reliability and validity

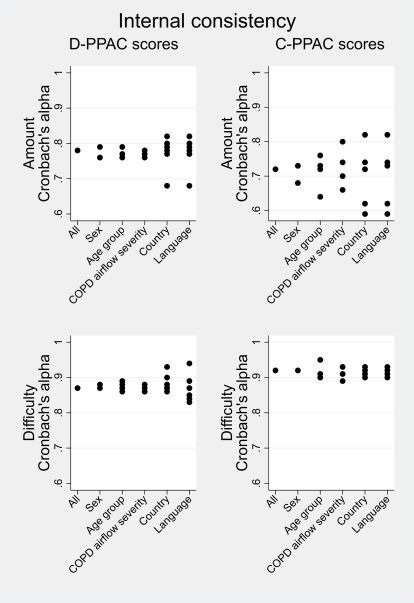

D-PPAC and C-PPAC scores showed strong internal consistency in all subjects (online supplemental table S6) and after stratification (figure 3). D-PPAC scores were reproducible over the 2-week period with ICCs>0.8 (online supplemental table S7). Bland-Altman plots showed no relevant differences between weeks 1 and 2 D-PPAC scores in stable patients (mean difference of 0 for amount, 1.2 for difficulty and 0.6 for total on the 100-point scores). Agreement laid within predefined limits and there was no pattern in differences over the range of values (online supplemental figure S1).

Figure 3.

Cronbach’s alpha of D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount and difficulty scores, overall and stratified by gender, age group (quartiles) and COPD airflow severity groups (reliability, internal consistency). C-PPAC, Clinical visit version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; D-PPAC, Daily version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument.

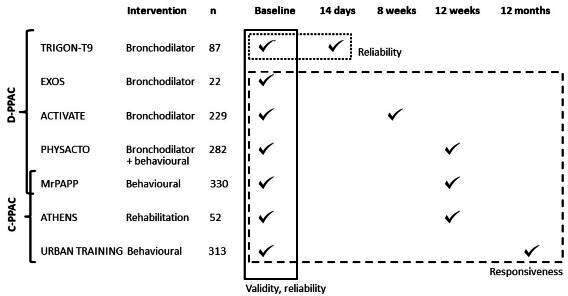

Both overall and after stratification, D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount scores exhibited weak correlations with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures, moderate correlations with exercise capacity and strong correlations with objective physical activity levels. Difficulty scores showed moderate-to-strong correlations with dyspnoea, HRQoL and exercise capacity and low correlations with objective physical activity level except for one country (The Netherlands) (table 2, figure 4). All D-PPAC and C-PPAC scores differentiated statistically across moderate-to-very severe COPD severity stages, dyspnoea grades (0–4) and tertiles of 6MWD, suggesting good known-group validity (online supplemental table S8).

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients* of D-PPAC and C-PPAC scores with dyspnoea, health-related quality of life, exercise capacity and objective physical activity level (convergent validity)

| D-PPAC | C-PPAC | |||||||||||

| Amount | Difficulty | Total | Amount | Difficulty | Total | |||||||

| Correlation | P value | Correlation | P value | Correlation | P value | Correlation | P value | Correlation | P value | Correlation | P value | |

| mMRC | −0.20 | <0.001 | −0.40 | <0.001 | −0.40 | <0.001 | −0.40 | <0.001 | −0.64 | <0.001 | −0.65 | <0.001 |

| CRQ dyspnoea | 0.16 | 0.006 | 0.68 | <0.001 | 0.59 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.045 | 0.61 | <0.001 | 0.56 | <0.001 |

| CRQ fatigue | 0.15 | 0.011 | 0.61 | <0.001 | 0.52 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.045 | 0.55 | <0.001 | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| CRQ emotional | 0.05 | 0.393 | 0.54 | <0.001 | 0.41 | <0.001 | −0.20 | 0.028 | −0.13 | 0.027 | −0.18 | 0.008 |

| CRQ mastery | 0.08 | 0.143 | 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.989 | 0.64 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 0.005 |

| CCQ symptoms | −0.20 | <0.001 | −0.56 | <0.001 | −0.50 | <0.001 | −0.18 | <0.001 | −0.55 | <0.001 | −0.45 | <0.001 |

| CCQ functional | −0.36 | <0.001 | −0.77 | <0.001 | −0.74 | <0.001 | −0.34 | <0.001 | −0.76 | <0.001 | −0.69 | <0.001 |

| CCQ mental | −0.28 | <0.001 | −0.55 | <0.001 | −0.52 | <0.001 | −0.19 | <0.001 | −0.50 | <0.001 | −0.42 | <0.001 |

| CCQ total | −0.33 | <0.001 | −0.75 | <0.001 | −0.70 | <0.001 | −0.31 | <0.001 | −0.75 | <0.001 | −0.65 | <0.001 |

| CAT total | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | −0.24 | <0.001 | −0.62 | <0.001 | −0.54 | <0.001 | |||

| 6MWD | 0.41 | <0.001 | 0.40 | <0.001 | 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.49 | <0.001 | 0.46 | <0.001 | 0.53 | <0.001 |

| MVPA | 0.67 | <0.001 | 0.12 | <0.001 | 0.53 | <0.001 | 0.80 | <0.001 | 0.30 | <0.001 | 0.67 | <0.001 |

*Correlation coefficients are in bold font when they met our assumptions (see online supplemental table S2 in the online data supplement) and normal font when they are higher or lower than expected.

CAT, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test; CCQ, clinical chronic obstructive pulmonary disease questionnaire; C-PPAC, Clinical visit version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; CRQ, chronic respiratory questionnaire; D-PPAC, Daily version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; mMRC, modified medical research council dyspnoea scale; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; 6MWD, 6 min walk distance; n.a, Not available.

Figure 4.

Correlation of D-PPAC and C-PPAC scores with CCQ-total, 6MWD and MVPA (convergent validity), overall and stratified by gender, age group (quartiles), COPD airflow severity groups, country and language. CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire; C-PPAC, Clinical visit versionof PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; D-PPAC, Daily version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument, MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; 6MWD,6 minwalking distance.

Responsiveness and MID

Large SRM values and significant between-arm differences were found for (follow-up—baseline) changes in D-PPAC difficulty scores after the PHYSACTO and ACTIVATE (bronchodilators) interventions and for changes in the D-PPAC amount score after MrPAPP (behavioural physical activity) intervention (table 3). Changes in C-PPAC difficulty score were significantly different after the ATHENS (pulmonary rehabilitation) intervention, as were changes in C-PPAC amount score after MrPAPP and URBAN TRAINING (behavioural physical activity) interventions. All scores were responsive to the self-reported rating of changes in physical activity experience (both worsening and improvement) and to the presence of COPD exacerbations during follow-up.

Table 3.

Changes in D-PPAC and C-PPAC scores after interventions and in relation to clinically relevant variables (responsiveness)

| D-PPAC | n | Amount score | Difficulty score | Total score | ||||||

| Change* | P† | SRMs | Change* | P† | SRMs | Change* | P† | SRMs | ||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| Response to interventions | ||||||||||

| PHYSACTO (12 week) | ||||||||||

| SMBM+placebo (ref.) | 63 | 1.8 (12.3) | 0.2 (1.1) | 0.8 (9.2) | 0.1 (0.9) | 1.3 (7.9) | 0.2 (1.0) | |||

| SMBM +tiotropium | 58 | 2.3 (9.8) | >0.999 | 0.2 (0.9) | 6.2 (12.0) | 0.021 | 0.6 (1.2) | 4.3 (8.2) | 0.178 | 0.6 (1.2) |

| SMBM +tiotropium/olodaterol | 60 | 4.7 (10.7) | 0.798 | 0.4 (1.0) | 5.9 (10.8) | 0.037 | 0.6 (1.0) | 5.3 (7.5) | 0.02 | 0.7 (1.0) |

| SMBM+tiotropium/olodaterol+exercise training | 62 | 4.4 (9.6) | >0.999 | 0.4 (0.9) | 5.9 (8.3) | 0.034 | 0.6 (0.8) | 5.1 (6.2) | 0.026 | 0.7 (0.8) |

| MrPAPP (12 week) | ||||||||||

| Usual care (ref.) | 144 | −2.9 (9.0) | −0.3 (0.8) | 0.9 (9.4) | 0.1 (1) | −1.0 (6.4) | −0.1 (0.9) | |||

| Telecoaching for physical activity | 141 | 2.1 (11.8) | <0.001 | 0.2 (1.1) | −0.8 (10.1) | 0.123 | −0.1 (1) | 0.6 (7.7) | 0.055 | 0.1 (1) |

| ACTIVATE (8 week) | ||||||||||

| Placebo (ref.) | 95 | 2.8 (14.3) | 0.2 (1.2) | −0.3 (8.5) | −0.03 (0.9) | 1.2 (6.7) | 0.2 (1.0) | |||

| Aclidinium bromide/formoterol fumarate | 105 | 2.5 (8.5) | 0.844 | 0.2 (0.7) | 3.0 (9.5) | 0.01 | 0.3 (1.0) | 2.7 (6.7) | 0.123 | 0.4 (1.0) |

| Change in relation to self-reported global rating of change (12 week for PHYSACTO and MrPAPP) | ||||||||||

| Change in physical activity experience overall | ||||||||||

| Much worse, worse, slightly worse | 74 | −5.3 (9.2) | <0.001 | −0.5 (0.9) | −2.4 (9.5) | 0.009 | −0.2 (1.0) | −3.8 (6.4) | <0.001 | −0.5 (0.9) |

| No change, slightly better (ref.) | 244 | 0.4 (9.7) | – | 0.04 (0.9) | 1.6 (9.8) | – | 0.2 (1.0) | 1.0 (6.6) | – | 0.1 (0.9) |

| Better, much better | 197 | 4.8 (11.5) | <0.001 | 0.5 (1.1) | 4.7 (10.7) | 0.005 | 0.5 (1.1) | 4.8 (8.0) | <0.001 | 0.6 (1.1) |

| Change in difficulty with physical activity | ||||||||||

| Much more/more/a little more difficult | 82 | −5.6 (10.6) | <0.001 | −0.5 (1.0) | −3.7 (9.5) | <0.001 | −0.4 (1.0) | −4.7 (6.7) | <0.001 | −0.6 (0.9) |

| No change, a little easier (ref.) | 281 | 1.1 (9.5) | – | 0.1 (0.9) | 1.9 (9.5) | – | 0.2 (1.0) | 1.5 (6.3) | – | 0.2 (0.9) |

| More easy, much more easy | 154 | 5.4 (11.6) | <0.001 | 0.5 (1.1) | 6.0 (10.7) | <0.001 | 0.6 (1.1) | 5.7 (8.0) | <0.001 | 0.8 (1.1) |

| Change in amount of physical activity | ||||||||||

| Much less/less/a little less active | 97 | −6.0 (9.9) | <0.001 | −0.6 (0.9) | −2.1 (10.1) | 0.001 | −0.2 (1.0) | −4.1 (6.9) | <0.001 | −0.6 (1.0) |

| No change, slightly better (ref.) | 222 | 0.3 (9.3) | – | 0.03 (0.9) | 2.3 (9.5) | – | 0.2 (0.9) | 1.3 (6.3) | – | 0.2 (0.9) |

| More/much more active | 198 | 6.2 (10.8) | <0.001 | 0.6 (1.0) | 4.3 (10.8) | 0.127 | 0.4 (1.1) | 5.2 (7.5) | <0.001 | 0.7 (1.1) |

| Changes according to COPD exacerbations during follow-up (8 week for ACTIVATE; 12 week for PHYSACTO and MrPAPP) | ||||||||||

| Any COPD exacerbation | ||||||||||

| No (ref.) | 443 | 2.1 (11.0) | 0.2 (1.0) | 2.8 (10.2) | 0.3 (1.0) | 2.5 (7.5) | 0.3 (1.0) | |||

| Yes | 96 | −3.0 (8.6) | <0.001 | −0.3 (0.8) | −0.6 (9.6) | 0.002 | −0.0 (1.0) | −1.8 (6.6) | <0.001 | −0.3 (1.0) |

| C-PPAC | n | Amount score | Difficulty score | Total score | ||||||

| Change* | P† | SRMs | Change* | P† | SRMs | Change* | P† | SRMs | ||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| Response to interventions | ||||||||||

| MRPAPP (12 week) | ||||||||||

| Usual care (ref.) | 114 | −4.3 (12.5) | −0.3 (1.0) | −1.7 (10.7) | −0.2 (1.1) | −3.0 (8.4) | −0.4 (1.0) | |||

| Telecoaching for physical activity | 112 | 2.9 (12.8) | <0.001 | 0.2 (1) | 0.2 (8.5) | 0.157 | 0.02 (0.9) | 1.5 (8.1) | <0.001 | 0.2 (1.0) |

| ATHENS (12 week) | ||||||||||

| Usual care (ref.) | 27 | −0.5 (13.3) | −0.0 (1.0) | −3.1 (10.4) | −0.3 (1.0) | −1.8 (8.5) | −0.2 (1.0) | |||

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | 25 | 5.9 (11.5) | 0.071 | 0.5 (0.9) | 5.3 (9.2) | 0.003 | 0.5 (0.9) | 5.6 (7.5) | 0.002 | 0.6 (0.8) |

| URBAN TRAINING‡ (12 m) | ||||||||||

| Usual care (ref.) | 74 | −0.2 (12.6) | −0.0 (1.0) | 0.4 (12.4) | 0.0 (1.0) | 0.2 (10.4) | 0.0 (1.0) | |||

| Urban training for physical activity | 29 | 4.6 (10.9) | 0.072 | 0.4 (0.9) | 4.8 (11.2) | 0.096 | 0.4 (0.9) | 4.7 (8.9) | 0.04 | 0.5 (0.9) |

| Change in relation to self-reported global rating of change (12 week for MRPAPP, 12 m for URBAN TRAINING‡) | ||||||||||

| Change in physical activity experience overall | ||||||||||

| Much worse, worse, slightly worse | 77 | −6.8 (12.7) | <0.001 | −0.5 (1.0) | −3.4 (13.5) | 0.016 | −0.4 (1.2) | −4.9 (10.1) | <0.001 | −0.6 (1.1) |

| No change, slightly better (ref.) | 165 | −0.4 (11.0) | – | −0.0 (0.9) | 0.6 (9.8) | – | 0.0 (0.9) | 0.0 (7.4) | – | −0.0 (0.8) |

| Better, much better | 84 | 5.8 (13.0) | <0.001 | 0.5 (1.0) | 2.3 (9.1) | 0.68 | 0.2 (0.9) | 4.1 (9.0) | 0.001 | 0.5 (1.0) |

| Change in difficulty with physical activity | ||||||||||

| Much more/more/a little more difficult | 84 | −6.3 (12.3) | <0.001 | −0.5 (1.0) | −4.4 (13.0) | <0.001 | −0.4 (1.2) | −5.1 (10.0) | <0.001 | −0.6 (1.1) |

| No change, a little easier (ref.) | 185 | 0.4 (11.5) | – | 0.0 (0.9) | 1.0 (9.5) | – | 0.1 (0.9) | 0.6 (7.6) | – | 0.1 (0.8) |

| More easy, much more easy | 58 | 5.9 (13.5) | 0.006 | 0.5 (1.0) | 3.9 (9.3) | 0.177 | 0.4 (0.8) | 5.0 (8.7) | 0.001 | 0.6 (0.9) |

| Change in amount of physical activity | ||||||||||

| Much less/less/a little less active | 91 | −6.7 (12.1) | <0.001 | −0.5 (1.0) | −2.4 (13.1) | 0.128 | −0.2 (1.2) | −4.3 (10.0) | <0.001 | −0.5 (1.1) |

| No change, slightly better (ref.) | 175 | 0.7 (11.8) | – | 0.1 (0.9) | 0.4 (10.0) | – | −0.0 (0.9) | 0.4 (8.2) | – | 0.0 (0.9) |

| More/much more active | 77 | 4.8 (12.5) | 0.039 | 0.4 (1.0) | 2.5 (9.0) | 0.441 | 0.2 (0.9) | 3.7 (7.8) | 0.017 | 0.4 (0.9) |

| Changes according to COPD exacerbations during follow-up (12 week for MRPAPP, 12 m for URBAN TRAINING‡) | ||||||||||

| Any COPD exacerbation | ||||||||||

| No (ref.) | 218 | 0.8 (12.8) | 0.1 (1.0) | 0.9 (9.8) | 0.1 (0.9) | 0.8 (8.4) | 0.1 (0.9) | |||

| Yes | 108 | −3.0 (12.5) | 0.008 | −0.2 (1.0) | −1.9 (12.4) | 0.022 | −0.2 (1.1) | −2.3 (10.2) | 0.003 | −0.3 (1.1) |

Parameters are in bold font when they met our assumptions (p value<0.05 and SRM≥0.5).

*Change calculated as 8 weeks score—baseline score in patients from ACTIVATE trial; 12 weeks score—baseline score in patients from PHYSACTO and MrPAPP trials; and 12 months—baseline in patients from Urban Training trial.

†P value of the score difference between groups, using multiple comparisons (Bonferroni method) after ANOVA test.

‡Using per protocol population.

ACTIVATE, Effect of Aclidinium/Formoterol on Lung Hyperinflation, Exercise Capacity and Physical Activity in Moderate to Severe COPD Patients; ANOVA, analysis of variance; ATHENS, Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program and PROactive Tool; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; C-PPAC, Clinical visit version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; D-PPAC, Daily version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; MrPAPP, Impact of Telecoaching Program on Physical Activity in Patients With COPD; PHYSACTO, Effect of Inhaled Medication Together With Exercise and Activity Training on Exercise Capacity and Daily Activities in Patients With Chronic Lung Disease With Obstruction of Airways; SMBM, self-management behaviour-modification; SRM, standardised response mean; URBAN TRAINING, Effectiveness of an Intervention of Urban Training in Patients With COPD.

From anchor-based estimates (online supplemental tables S4 and S9), we suggest a MID of 6 for the D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount and difficulty scores and 4 for the total scores. Distribution estimates for MDC produced very similar values.

Discussion

By pooling data from a diverse population of patients with COPD from seven randomised controlled trials, we are the first to report the performance of the D-PPAC and C-PPAC instrumentsin COPD. Key findings are that D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount, difficulty and total scores (1) exhibit wide variation appropriate to patients with differing clinical characteristics, (2) show good internal consistency and construct validity across sex, age group, COPD severity, countries and languages, (3) are responsive to interventions and to changes in clinically relevant variables and (4) we established a MID of 6 for the amount and difficulty scores and of 4 for the total scores.

This study provides important information for the future use of PPAC instruments. First, we found a wide distribution of D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount, difficulty and total scores, as expected by the fact that patients included in the seven clinical trials were quite diverse in terms of disease severity and recruitment settings. Such variability in the scores supports the use of PPAC instruments to capture diversity in physical activity amount and difficulty as experienced by patients with COPD. Second, patients scored generally higher, that is, better, in the difficulty than in the amount domain. Qualitative and quantitative data from the development and initial validation studies of PPAC instruments,11 20 and current knowledge on physical activity and COPD,23 support that amount and difficulty are indeed two different dimensions of physical activity experience. Third, the amount domain covered virtually all potential values from 0 to 100, which favours the notion that combining few questionnaire items with two activity monitor variables allows better capture of a wide spectrum of the patient-centred construct ‘amount of physical activity’ than with an activity monitor alone, as previously shown.11 Fourth, the lack of patients scoring less than 25 in the difficulty domain (ie, reporting most difficulty) could be due to underreporting or to the fact that none of the trials included exacerbating or extremely severe COPD patients. Further studies should test the PPAC instruments in these subpopulations. Finally, C-PPAC scores were higher than D-PPAC scores in all domains, with differences of >10 points in the amount domain (see MrPAPP D-PPAC and C-PPAC scores in online supplemental table S4). This could be attributed to recall bias in the weekly report towards higher amount of physical activity or to different cut-offs used for steps and VMU/min between D-PPAC and C-PPAC versions (although the latter could not mathematically explain a>10 point difference). In any case, these results suggest that D-PPAC and C-PPAC instruments should not be used interchangeably in the same patient or study.

All scores of D-PPAC and C-PPAC instruments demonstrated good internal consistency and construct validity across sexes, age groups, COPD severities, countries and languages and very similar to those presented in the original development and validation study.11 One exception was the moderate correlation (higher than expected) between D-PPAC difficulty and MVPA in the Netherlands, including only 34 patients, that we consider a chance finding given that the rest of correlations in the Netherlands as well as all correlations for patients in Belgium (sharing the same language and geographic/climatic conditions as the Dutch) were within the range of other countries. Remarkably, observed correlations between PPAC scores and dyspnoea, HRQoL, exercise capacity and objective physical activity were very close to the a priori hypothesised, supporting that the PPAC instruments measure what they are meant to measure.

In studies using pharmacological interventions, significant differences were observed in the D-PPAC difficulty score after treatment with bronchodilators (ACTIVATE and PHYSACTO).12 16 In non-pharmacological intervention studies, both D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount scores significantly improved after 12 weeks of telecoaching (MrPAPP),15 a signal also observed in the ‘control’ group of PHYSACTO, which also received a self-management behavioural intervention that included coaching towards physical activity. As expected, C-PPAC difficulty score significantly improved after 12 weeks of an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programme (ATHENS).13 Finally, the C-PPAC total score was able to detect even after 12 months a significant improvement following a behavioural and community-based exercise intervention (URBAN TRAINING).18 It is of note that prior to the trials included in this study, no interventions were available with a known effect on patients’ experience of physical activity. Our analyses support positive effects of bronchodilator therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation and physical activity behavioural interventions on these domains, which is relevant to COPD management. Finally, PPAC scores were able to detect changes (improvement or worsening) in self-reported physical activity experience and to decrease (worsen) significantly in patients who had experienced exacerbations during follow-up (8 weeks, 12 weeks or 12 months, depending on the study). Altogether makes these tools useful to serve as endpoints in clinical trials.

We suggest a MID of 6 for the amount and difficulty scores and of 4 for the total score, in scales ranging from 0 to 100. These values can identify differences in clinically relevant concepts such as HRQoL and patient self-report of physical activity change. Importantly, distribution-based estimates approximating the MDC gave very similar values (table 4), suggesting that changes that are important to patients can be detected by the PPAC instruments. Given the prognostic value of objective physical activity,2 as traditionally measured by an activity monitor, further studies should assess whether the defined MIDs for physical activity experience relate to morbidity and mortality of COPD.

Table 4.

Anchor-based estimates of the MID and distribution-based estimates of the MDC for D-PPAC and C-PPAC amount, difficulty and total scores

| D-PPAC | C-PPAC | |||||

| Amount | Difficulty | Total | Amount | Difficulty | Total | |

| Anchor based | ||||||

| Change in CCQ total* | 5.7 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 3.3 | ||

| Change in amount of physical activity† | 6.2 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 3.7 | ||

| Change in difficulty with physical activity† | 5.4 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.0 | |

| Change in physical activity experience overall† | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 4.1 | ||

| Distribution based | ||||||

| 0.5 of Cohen’s effect size | 6.7 | 7.2 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 6.0 |

| 1 SEM (of ICC) | 5.4 | 5.4 | 3.8 | |||

*Mean difference (final–baseline) in scores in patients who changed ≤−0.4 points in CCQ score.

†Mean difference (final–baseline) in scores in patients who rated their physical activity change as ‘better’ in amount, difficulty or overall.

CCQ, clinical COPD questionnaire; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; C-PPAC, Clinical visit version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; D-PPAC, Daily version of PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; MDC, minimal detectable change; MID, minimal important difference; SEM, standard error of measurement.

The main limitation of our study is the lack of inclusion of exacerbating or recently exacerbated patients, which neither allow us to test the validity of the PPAC instruments in patients experiencing the most difficulty with physical activity nor to test the responsiveness of PPAC scores to interventions during exacerbations. Also, the PPAC instruments were tested in participants of clinical trials, who do not always reflect the general population of patients with COPD. However, some of the included trials recruited patients from primary care or with severe comorbidities. Finally, the heterogeneity in interventions and recruitment periods did not allow us to analyse if responsiveness differed by season, as previously shown in pulmonary rehabilitation.24

By using a number of different studies, conducted in different patient populations, the main strength of this study is that it covered a wider range of COPD disease severities, ages, objective physical activity levels and clinical determinants than what is usually seen in other questionnaire/patient-reported outcome development programmes. Moreover, patients from different countries and language groups were enrolled, supporting the use of the PPAC instruments in millions of patients with COPD in Europe and the North America. Also, responsiveness was tested against different types of interventions, which allowed understanding of how different domains of physical activity experience vary in response to different types of interventions, as discussed above. The diverse follow-up periods, that reflect expectations about when changes will occur after each intervention, show that PPAC scores are able to identify changes in physical activity experience occurring at different time spans. Finally, although the study pooled data from independent drug and non-drug clinical trials with their own research objectives, the analysis was based on a priori defined hypothesis for all validation parameters.

Based on the previous11 and above evidence supporting the content validity, psychometric properties and usability of the PPAC instruments, the EMA in its final qualification opinion agrees that both instruments are suitable to capture physical activity experience in COPD patients and can thus be used as endpoints in clinical trials.25 Our results further support their use in future clinical trials and observational research studies. The fact that more than 1300 patients with COPD (83% of those participating in the original trials) completed the PPAC questionnaires and wore an activity monitor for at least 3 days in a week, which confirms acceptability and feasibility in a range of countries, languages and clinical scenarios. The use of the D-PPAC or C-PPAC version should depend on study objectives and try to balance patients’ burden. The D-PPAC questionnaire is shorter (seven questions) and less prone to recall bias, but requires daily report and availability of electronic-handled devices to fill in the questionnaire. Thus, the D-PPAC instrument is more likely to be used where daily variations in physical activity experience or other outcomes or covariates are expected or in regulatory clinical trials (by industry members) where physical activity experience is a primary outcome to obtain a label claim. The C-PPAC questionnaire (12 questions) is answered only once in a week and can also be completed in a website or in paper and pen, which increases feasibility but is subjected to some degrees of recall bias. Therefore, the C-PPAC instrument is more likely to be used where physical activity experience stability can be expected in a 1-week window, where patient burden of completing questionnaires is high or in pragmatic studies to gather ‘real-world’ evidence. A ‘PPAC User’s Guide’ is available from the authors describing the instruments, their administration procedures, scoring and translations available.

In conclusion, the D-PPAC and C-PPAC instruments are valid and reliable across sexes, age groups, COPD severities, countries and languages and are responsive to drug and non-drug treatments and changes in clinically relevant variables.

Acknowledgments

We like to thank the input from the PROactive project Ethics Board, Advisory Board and Patient Input Platform.

Footnotes

Twitter: @judithgarciaaym, @Demeyer_H, @EleGim, @COPDdoc

Contributors: JG-A carried out statistical analysis and prepared the first draft of the paper. All authors (i) provided substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, (ii) revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, (iii) approved the final version and (iv) agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. JG-A had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: Supported by the European Commission Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking [IMI JU number 115011]. This project was also supported by the NIHR Respiratory Biomedical Research Unit at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College who part-funded MIP’s salary. ISGlobal acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the 'Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2019-2023' Program (CEX2018-000806-S), and support from the Generalitat de Catalunya through the CERCA Program. HD is a postdoctoral research fellow of the FWO Flanders.

Disclaimer: No involvement of funding sources in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: JG-A reports other from AstraZeneca, other from Esteve, other from Chiesi, other from Menarini, outside the submitted work. SC-R reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. DE reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. NI reports personal fees from Almirall, outside the submitted work. NK reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. MIP reports personal fees from Philips, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from GSK, during the conduct of the study. MS reports personal fees from Chiesi, outside the submitted work. MT reports personal fees and other from GSK, outside the submitted work. TT reports grants from IMI-JU PROactive grant, during the conduct of the study; other from Boehringer Ingelheim, other from AZ Belgium, outside the submitted work.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. This study pools deidentified participants' data from seven previously published trials with different ownership and availability conditions. Table S1 in supplementary material provides sponsor name and registration details for each trial.

Contributor Information

PROactive consortium:

Nathalie Ivanoff, Niklas Karlsson, Solange Corriol-Rohou, Ian Jarrod, Damijen Erzen, Mario Scuri, Roberta Montaccini, Nadia Kamel, Maggie Tabberer, Katrina McLoughlin, Matthew Allinder, Thierry Troosters, Fabienne Dobbels, Heleen Demeyer, Judith Garcia-Aymerich, Ignasi Serra, Elena Gimeno-Santos, Netherlands Asthma Foundation, Pim de Boer, Karoly Kulich, Alastair Glendenning, Michael I Polkey, Nick S Hopkinson, Ioannis Vogiatzis, Zafeiris Louvaris, Thys van der Molen, Corina De Jong, Roberto A Rabinovich, Bill MacNee, Milo A Puhan, and Anja Frei

References

- 1. Vorrink SNW, Kort HSM, Troosters T, et al. Level of daily physical activity in individuals with COPD compared with healthy controls. Respir Res 2011;12:33–40. 10.1186/1465-9921-12-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gimeno-Santos E, Frei A, Steurer-Stey C, et al. Determinants and outcomes of physical activity in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Thorax 2014;69:731–9. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giacomini M, DeJean D, Simeonov D, et al. Experiences of living and dying with COPD: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2012;12:1–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barisic A, Leatherdale ST, Kreiger N. Importance of frequency, intensity, time and type (FITT) in physical activity assessment for epidemiological research. Can J Public Health 2011;102:174–5. 10.1007/BF03404889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS, et al. Quantifying physical activity in daily life with questionnaires and motion sensors in COPD. Eur Respir J 2006;27:1040–55. 10.1183/09031936.06.00064105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lareau SC, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Janson-Bjerklie S, et al. Development and testing of the pulmonary functional status and dyspnea questionnaire (PFSDQ). Heart Lung 1994;23:242–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, et al. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George's respiratory questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:1321–7. 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miravitlles M, Anzueto A, Legnani D, et al. Patient's perception of exacerbations of COPD--the PERCEIVE study. Respir Med 2007;101:453–60. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hogg L, Grant A, Garrod R, et al. People with COPD perceive ongoing, structured and socially supportive exercise opportunities to be important for maintaining an active lifestyle following pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative study. J Physiother 2012;58:189–95. 10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70110-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Guidance for industry. patient-reported outcomes measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims guidance for industry., 2009. Available: www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf [Accessed 27 Oct 2019].

- 11. Gimeno-Santos E, Raste Y, Demeyer H, et al. The proactive instruments to measure physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2015;46:988–1000. 10.1183/09031936.00183014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dobbels F, de Jong C, Drost E, et al. The proactive innovative conceptual framework on physical activity. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1223–33. 10.1183/09031936.00004814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Watz H, Troosters T, Beeh KM, et al. Activate: the effect of aclidinium/formoterol on hyperinflation, exercise capacity, and physical activity in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017;12:2545–58. 10.2147/COPD.S143488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Louvaris Z, Spetsioti S, Kortianou EA, et al. Interval training induces clinically meaningful effects in daily activity levels in COPD. Eur Respir J 2016;48:567–70. 10.1183/13993003.00679-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harvey-Dunstan TC, Radhakrishnan J, Houchen-Wolloff L, et al. Correlation between quadriceps strength and five exercise tests in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [abstract]. Eur Respir J 2014;44:P3682. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Demeyer H, Louvaris Z, Frei A, et al. Physical activity is increased by a 12-week semiautomated telecoaching programme in patients with COPD: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2017;72:415–23. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Troosters T, Maltais F, Leidy N, et al. Effect of bronchodilation, exercise training, and behavior modification on symptoms and physical activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198:1021–32. 10.1164/rccm.201706-1288OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hajol E, Piccinno A, Viaud I, et al. Efficacy and safety of extrafine glycopyrronium bromide pMDI (CHF 5259) in COPD patients [abstract]. Eur Respir J 2016;48:PA4065. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arbillaga-Etxarri A, Gimeno-Santos E, Barberan-Garcia A, et al. Long-term efficacy and effectiveness of a behavioural and community-based exercise intervention (urban training) to increase physical activity in patients with COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J 2018;52:1800063. 10.1183/13993003.00063-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, ATS/ERS Task Force . Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004;23:932–46. 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. EMA Committee for medicinal products for human use (EMA). biomarkers qualification: guidance to applicants, 2008. Available: www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000043.jsp [Accessed 27 Oct 2019].

- 22. Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, et al. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:102–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koolen EH, van Hees HW, van Lummel RC, et al. "Can do" versus "do do": a novel concept to better understand physical functioning in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med 2019;8:340. 10.3390/jcm8030340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sewell L, Singh SJ, Williams JE, et al. Seasonal variations affect physical activity and pulmonary rehabilitation outcomes. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2010;30:329–33. 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181e175f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. European Medicines Agency Qualification opinion on proactive in COPD. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/qualification-opinion-proactive-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd_en.pdf [Accessed 27 Oct 2019].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

thoraxjnl-2020-214554supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)