Abstract

Konjac glucomannan oligosaccharide has attracted much attention due to its broad biological activities. Specific glucomannan degrading enzymes are effective tools for the production of oligosaccharides from konjac glucomannan. However, there are still few reports of commercial enzymes that can specifically degrade konjac glucomannan. The gene ppgluB encoding a glucomannanase consisting of 553 amino acids (61.5 kDa) from Paenibacillus polymyxa 3–3 was cloned and heterologous expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). The recombinant PpGluB showed high specificity for the degradation of konjac glucomannan. Moreover, the hydrolytic products of PpGluB degrade konjac glucomannan were a series of oligosaccharides with degrees of polymerisation of 2–12. Furthermore, the biochemical properties indicated that PpGluB is the optimal active at 45 to 55 °C and pH 5.0–6.0, and shows highly pH stability over a very broad pH range. The present characteristics indicated that PpGluB is a potential tool to be used to produce oligosaccharides from konjac glucomannan.

Keywords: Konjac glucomannan, Glucomannanase, Paenibacillus polymyxa, Substrate specificity, Konjac glucomannan oligosaccharides

Introduction

Konjac glucomannan (KGM) has entered the field of vision of many industries because of its characteristics of promising renewable replacement, rich, low cost, biodegradable and strong biocompatibility (Behera and Ray 2016; Li et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2009). It is a water-soluble plant polysaccharide derived from the tubers of Amorphophallus konjac C. Koch (Liu et al. 2019). It is composed of glucose and mannose units through β-1,4 glycosidic bonds in a ratio of 1:1.6 or 1:1.4, respectively (Huang et al. 2002; Nishinari and Takahashi 2003), and contained an acetyl group substitution at the C-6 position in every 19 glyco units (Du et al. 2012). Due to its special structure and excellent properties, KGM is widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries as a gelling agent (Akesowan 2015), thickener (Tester and Al-Ghazzewi 2017), water retention agent (Zhang et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2013) and potential material for development of functional foods (Fang and Wu 2004; Jimenez-Colmenero et al. 2012).

As a food source and traditional medicine, the products of KGM have been rated as one of the “Top Ten Healthy Foods” by the World Health Organization (Behera and Ray 2016). In recent years, some studies have shown that konjac glucomannan oligosaccharides (KGOS), a degradation product of KGM, has stronger biological activity in the field of life sciences, such as antitumor (Li et al. 2020; Nguyen et al. 2019), antioxidant (Connolly et al. 2010) and probiotic activity (Al-Ghazzewi et al. 2007). Besides, KGOS are more widely used due to its small molecular and high solubility. There are several methods including physical, chemical and enzymatic hydrolysis, which have been used for KGM being degraded into oligosaccharides (Hu et al. 2019; Jian et al. 2018; Jin et al. 2014). Among them, the enzymatic method provides an efficient, specific, environmentally friendly and energy-saving method for preparing KGOS. Many literatures reported that mannanase, glucanase and glucomannanase can hydrolyze KGM to obtain oligosaccharides. Among them, there have been many studies on mannanase and glucanase, which generally have broad substrate specificity (such as glucomannan, β-glucan, galactomannan, mannan and xylan) (Jiang et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2016; Mikkelson et al. 2013; Zhu et al. 2020). There are few studies on glucomannanase, and fewer reported on glucomannanase with specific degradation KGM. Therefore, the development of a highly specific KGM degrading enzyme is more conducive to the separation of KGM oligosaccharides in the degradation of crude resources. According to the structural composition of KGM, the KGM degradation enzymes include endo-β-1,4-glucanase (EC 3.2.1.4) (Mikkelson et al. 2013) and endo-β-1,4-mannanase (EC 3.2.1.78) (Tuntrakool and Keawsompong 2018). Based on sequence similarity, the glycoside hydrolase is divided into different glycoside hydrolase (GH) families (Lombard et al. 2013). GH5 family is a (α/β)8 barrel-like structure that hydrolyzes glycosidic bonds via an acid/base retention mechanism, and hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds is catalyzed by two strictly conserved glutamic acids (Dorival et al. 2018; Venditto et al. 2015). According to phylogenetic analysis, GH5 family is divided into 54 subfamilies, of which the GH5_4 subfamily includes endo-β-1,4-glucanase (EC 3.2.1.4) (Lombard et al. 2013; Venditto et al. 2015). The GH5_4 subfamily is usually linked to carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) of different families, thus showing ligand specificity that reflects the substrate specificity of related catalytic modules (Venditto et al. 2015). Most CBM domains are related to enzyme activity, and more importantly, directly affect the specific selection of enzyme for substrate.

In this study, a glucomannanase was cloned from a KGM degradation strains Paenibacillus polymyxa 3–3 and over-expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3). The recombinant enzyme showed high hydrolysis activity and specific degradation toward KGM. The biochemical properties and kinetics of this enzyme were characterized. And, the reaction mechanism of the recombinant enzyme was explored and analyzed.

Materials and methods

Materials and chemicals

Paenibacillus polymyxa 3–3 was isolated from Ankang, Shaanxi and preserved in our laboratory. KGM was purchased from Ruibio Company (Hefei, China). Locust bean gum, guar gum and xanthan gum were purchased from Shanghai Keyuan Industrial Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Carboxymethyl cellulose and microcrystalline cellulose were obtained from Sigma Ltd (Shanghai, China). Curdlan was purchased from Takeda-kirin Company (Shanghai, China). PASC was prepared as originally reported in our laboratory (Zhou et al. 2019). Unless otherwise stated, all molecular biology reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). Synthetic primers along with sequencing services were provided by BGI Tech (Beijing, China).

Cloning, expression and purification of glucomannanase gene ppgluB from Paenibacillus polymyxa 3–3

In the previous work, the laboratory selected a strain of Paenibacillus polymyxa 3–3 that can effectively degrade KGM from the rotting konjac in the konjac planting area (unpublished data). Based on the existing data of Paenibacillus polymyxa in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database, the endo-β-1-4-glucanase gene (named ppgluB) was screened out according to the structural characteristics of KGM. According to sequence similarity analysis, ppgluB belongs to the GH5_4 family. There have been reports that the GH5_4 family of enzymes can degrade glucan-containing substrates/KGM (Dorival et al. 2018; Venditto et al. 2015). Therefore, it is speculated that PpGluB may also have the ability to degrade glucan-containing substrates/KGM. The degenerate primers for cloning ppgluB were designed as follows: a forward primer containing an NdeI site (underlined) 5′-CGGACGCATATGGYYGAAWCKGACGRACAAG-3′ and a reverse primer containing an XhoI site (underlined) 5′-GATGATCTCGAGAGAYGTCRYDCCCGTCAC-3′. The gene was amplified by PCR from Paenibacillus polymyxa 3–3 genomic DNA and then ligated into the NdeI–XhoI sites of the expression vector pET21a through double digestion. The recombinant plasmid pET21a/ppgluB contained a N-terminal (His)6-tagged frame and finally transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3). Expression of the recombinant strain was achieved by addition of 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) and incubation at 16 °C overnight in a 180-rpm shaker. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and then disrupted by ice bath sonication. To purify the (His)6-tagged recombinant PpGluB, the supernatant of centrifugation was loaded onto 10 mL NTA-Ni Sepharose resin (GE Healthcare, Beijing, China) pre-equilibrated with binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl). The protein was washed with 5 column volumes (CV) binding buffer, then washed with 5 CV wash buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole), and finally washed with 6 CV elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole). The purified PpGluB was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and the concentration of purified PpGluB was determined by the BCA Protein Concentration Assay (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Activity assay of PpGluB

The glucomannanase activity of PpGluB was determined spectrophotometrically (540 nm) using the method of 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS), with glucose being a standard for the calibration curves (Li et al. 2018). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes 1 µmol of hydrolysate per milligram per minute.

To explore the specificity of PpGluB among different linkage polysaccharides, the following substrates were analyzed: β-glucan from KGM, xanthan gum, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), PASC, microcrystalline cellulose and curdlan; mannan from locust bean gum (LBG) and guar gum. The standard reaction was performed in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) using the above polysaccharides as the substrates (0.5%, w/v), and incubated at 45 °C for 10 min after adding 21.13 µg enzyme, then, the reaction was stopped in boiling water bath for 10 min.

Biochemical properties of PpGluB

The effect of pH on PpGluB activity was measured by incubating the enzyme with KGM (0.5%, w/v) dissolved in different buffers [Glycine–HCl buffer (pH 3.0), sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0 and 5.0), phosphate buffer (pH 6.0 and 7.0), Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0) and Glycine–NaOH buffer (pH 9.0 and 10.0)] under standard assay conditions. The optimal temperature of PpGluB activity was evaluated by incubating the enzyme with KGM (0.5%, w/v) at different temperatures ranging from 25 to 85 °C with 10 °C intervals under optimal pH. For pH stability, the residual activity of the enzyme was recorded after been incubated for 24 h at different pH at 4 °C. Buffers used for different pH values are listed above. The thermostability of PpGluB was tested by incubating the enzyme for 1 h at different temperatures ranging from 25 to 85 °C.

The effect of chemicals on PpGluB activity was also tested using Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and ten metal ions (K+, Fe2+, Ba2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Cu2+, Fe3+ and Co2+) with a final concentration of 1 mM. Here, KGM was used as the substrate and a reaction in the absence of the metal ion served as control (residual activity was defined as 100%). Enzyme activity assays were performed under the standard conditions as mentioned above. The kinetic constants of PpGluB were also determined.

The Michaelis–Menten equation was determined according to the Lineweaver–Burk method. Km and Vmax values were determined using KGM as a substrate. The reactions were carried out in a 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) for 5 min with a series of substrate concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 mg/mL.

Hydrolysis product analysis of PpGluB

The hydrolysis products of the PpGluB degradation of KGM were qualified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF–MS). The degraded products of KGM were obtained after 24 h of digestion. An AB SCIEX MALDI-TOF/TOF 5800 profile was used to perform the mass spectrometry.

Homology modeling and analysis of the degradation mechanism

The homology model of PpGluB was generated by MODELLER program (version 9.19) (Webb and Sali 2016) using the characterized cellulases (PDB: 4V2X, 5E0C, 5E09 and 5XRC) as the template. To explore the enzyme–ligand interaction during the reaction, we docked PpGluB with glucohexaose using AutoDock 4 and Autodock Tools (version 1.5.6) (Morris et al. 2009). The charge on the surface of the binding pocket was analyzed, and key amino acids that may interact with the substrate were analyzed according to the results.

Results and discussion

Cloning, expression and purification of PpGluB

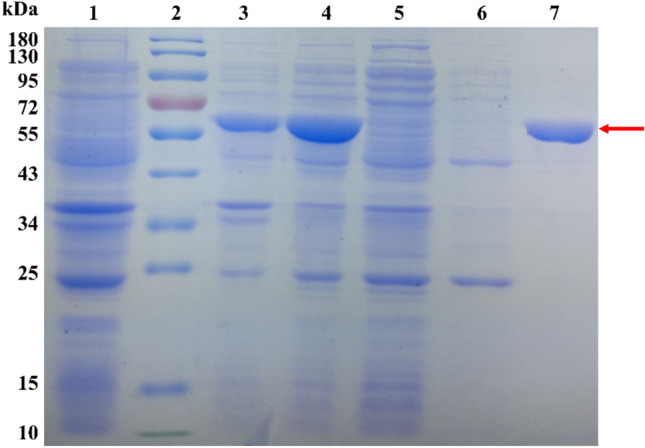

The gene of ppgluB was cloned from Paenibacillus polymyxa 3–3 that can degrade KGM. The ORF of ppgluB consisted of 1662 bp (GenBank accession number: MW423636) and encoded 553 amino acids with molecular mass of 61,453.75 Da. The recombinant PpGluB was purified using Ni–NTA sepharose affinity chromatography and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 1, the recombinant PpGluB can expressed efficiently in E. coli and purified by Ni–NTA resin. The purification results were listed in Table 1, a 1.93-fold purification was achieved with a yield of 48.63%.

Fig. 1.

SDS-PAGE of the purified PpGluB. Lane 1: uninduced culture; lane 2: protein marker; lane 3: precipitation after ultrasonic cleavage; lane 4: cure enzyme; lane 5: protein flow through Ni–NTA resin; lane 6: washing by wash buffer contained 20 mM of imidazole; Lane 7: washing by elution buffer contained 250 mM of imidazole

Table 1.

The purification of PpGluB

| Purification process | Wet weight cell pellet (g) | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Purification factor | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude enzyme | 2.05 | 323.68 | 188.41 | 20.37 | 1.00 | 100 |

| NTA-Ni resin | − | 139.91 | 91.61 | 39.29 | 1.93 | 48.63 |

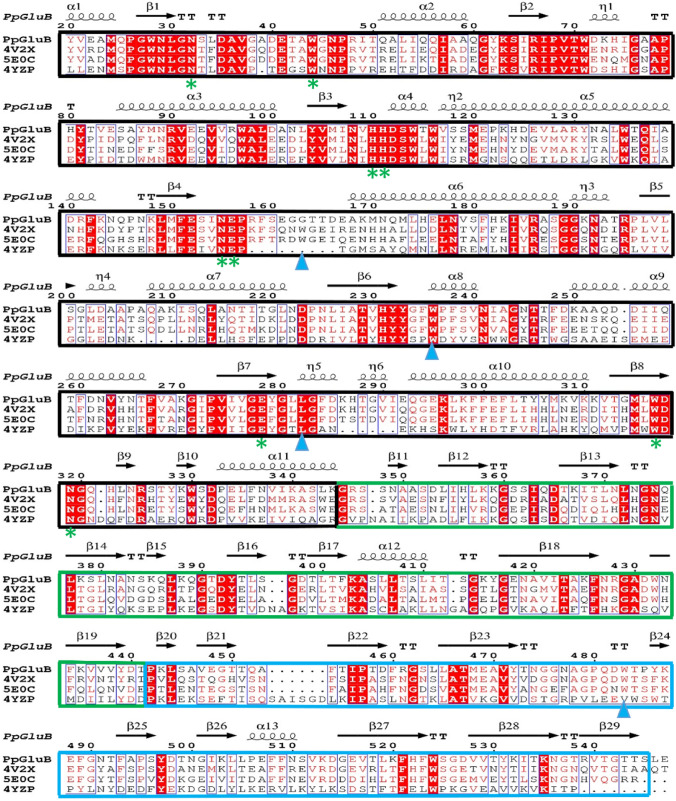

Based on the five characterized proteins (4V2X.A, 5E0C.A, 5XRC.A, 5E09.A and 4YZP.A) with the high homology in the NCBI database with the programme BLASTP, the alignment analysis with PpGluB was obtained as Fig. 2 showed. PpGluB exhibits high homology (55% sequence identity to 4V2X) with the reported endoglucanase/cellulases from various sources (such as Bacillus halodurans, Bacillus sp. BG-CS10, Bacillus licheniformis, Clostridium cellulovorans and Zobellia galactanivorans). Sequence alignment indicates that PpGluB is a multi-domain protein including an N-terminal catalytic module of GH5_4 family, a C-terminal CBM46 domain, and an internal immunoglobulin (Ig)-like module. Several studies have shown that members of the GH-A family have two conserved catalytic residues of glutamate at the end of β-strands 4 and 7 (Henrissat et al. 1995; Venditto et al. 2015). From the sequence analysis of PpGluB, Glu156 and Glu278 correspond to glutamate at the end of β-strands 4 and 7, respectively. Furthermore, being a member of the GH5_4 family, PpGluB contains several other conserved residues, such as Asn32, Trp44, His110, His111, Asn155, Trp317 and Asn319, which are key amino acids located on the catalytic pocket and involved in substrate interaction (Liberato et al. 2016). Several sequence similar enzymes of PpGluB have been reported to have the ability to degrade glucan-containing substrates (Dorival et al. 2018; Liberato et al. 2016; Venditto et al. 2015). The research by Venditto et al. (2015) reported that the residue that played an important contribution in ligand recognition on CBM46 is Trp501 (corresponding to Trp483 of PpGluB), and the residues that play a key role in substrate recognition in GH5 are Trp181, Trp254 and Leu300 (corresponding to Gly163, Trp236 and Leu282 of PpGluB, respectively). However, the mutation of tryptophan greatly reduces the enzyme’s affinity for both xyloglucan and barley β-glucan. The result of sequence alignment shows that the residue at position 163 is not conservative (mutated from tryptophan to glycine), which may affect the recognition of the substrate.

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequences alignments of PpGluB and related glucanase. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalX2 and ESPript 3.0. The sequence alignment includes the enzymes molecules similar to PpGluB, namely, the sequence of PpGluB, glucomannanase from Paenibacillus polymyxa 3–3; 4V2X, endo-β-1,4-glucanase from Bacillus halodurans; 5E0C, cellulase from Bacillus sp. BG-CS10 and 4YZP, cellulose hydrolase from Bacillus licheniformis. The N-terminal catalytic module of GH5_4 family was marked with a black box, the immunoglobulin (Ig)-like module was marked with a green box, and the C-terminal CBM46 domain was marked with a blue box. The conservative residues of PpGluB were marked with a green asterisk. The predicted key residues for ligand recognition are indicated by blue triangles

Substrate specificity of PpGluB

The substrate specificity of PpGluB towards 8 different polysaccharides was investigated. As shown in Table 2, the results indicated that PpGluB displayed the specific activity towards KGM, but little to no significant activity for other substrates, only very low activity (0.58 ± 0.50 U/mg) for carboxymethyl cellulose was detected. According to substrate specificity, PpGluB can degrade glucomannan, but no significant activity on cellulose and galactomannan, thereby confirming that PpGluB has the function of glucomannanase. This result is similar to the glucanase PpGluA derived from the same strain Paenibacillus polymyxa (Li et al. 2020), but quite differed from the substrate specificity of most reported β-1,4-glucanases. Several glucanases from GH5_4 subfamily have been reported to be able to hydrolyze multiple glucan-containing substrates, such as BhCel5B from Bacillus halodurans, showed degrading activity to barley β-glucan and xyloglucan (Venditto et al. 2015), ZgEngAGH5_4 from Zobellia galactanivorans showed broad substrate specificity towards mixed-linkage glucan, lichenan, glucomannan, xyloglucan and CMC (Dorival et al. 2018).

Table 2.

Substrate specificity of PpGluB

| Substrate | Hydrolytic activity (U/mg) | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| KGM | 39.29 ± 1.11 | 100 ± 2.9 |

| xanthan gum | NA | NA |

| carboxymethyl cellulose | 0.58 ± 0.50 | 2.0 ± 1.8 |

| PASC | NA | NA |

| microcrystalline cellulose | NA | NA |

| curdlan | NA | NA |

| locust bean gum | NA | NA |

| guar gum | NA | NA |

NA the relative activity of PpGluB hydrolysis of KGM was not detected

To explore the reason why PpGluB is different from other glucanases/cellulases in terms of substrate specificity, we compared the structure of PpGluB (homology modeling) with other resolved glucanases/cellulases. The result show that PpGluB has high structural similarity compare with other glucanases/cellulases, but there is significant conformational change in a loop of GH5 domanin (Fig. 5b). At this loop, the conformation of most proteins is different from that of PpGluB, and the properties of 5E0C in a similar conformation have not been characterized yet. According to previous reports (Dorival et al. 2018; Liberato et al. 2016; Venditto et al. 2015), a tryptophan on this loop plays an important role in substrate recognition, and PpGluB mutates to alanine at the tryptophan position, which may affect the enzyme's recognition of substrates.

Fig. 5.

Structure of PpGluB and interaction of the substrate-binding cleft of PpGluB with glucohexaose. a The complete function module of PpGluB is shown as a cartoon illustration. b Key amino acid display in CBM and comparison of multiple enzyme loops. Key amino acid with CBM46 (yellow), PpGluB (red), 4V2X (orange), 3NDY (green), 6GL2 (blue). c Description of the catalytic pocket and substrate-binding mode of PpGluB. Glucohexaose (green), two catalytic glutamine acid residues (yellow) and amino acids within 5 Å (blue)

Among glucomannanases, compared with β-1,4-mannanase, there are fewer studies on β-1,4-glucanase to degrade glucomannan, and its hydrolysis rate for glucomanann is relatively weak. For instance, PpGluB (39.29 U/mg) and endo-β-1,4-glucanase (CelL) (2.5 U/mg) from Cellulosimicrobium funkei (Kim et al. 2016) and glucanase (Cel9C) (57 U/mg) from Clostridium josui (Ning et al. 2015) exhibited much lower activity than that of mannan Man113A (370.4 U/mg) from Alicyclobacillus sp. (Xia et al. 2016) and AaManA (1056 U/mg) from Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius (Zhang et al. 2008) toward konjac glucomannan. Although the activity of PpGluB is not the highest, it has the advantage of substrate specificity.

Biochemical properties of PpGluB

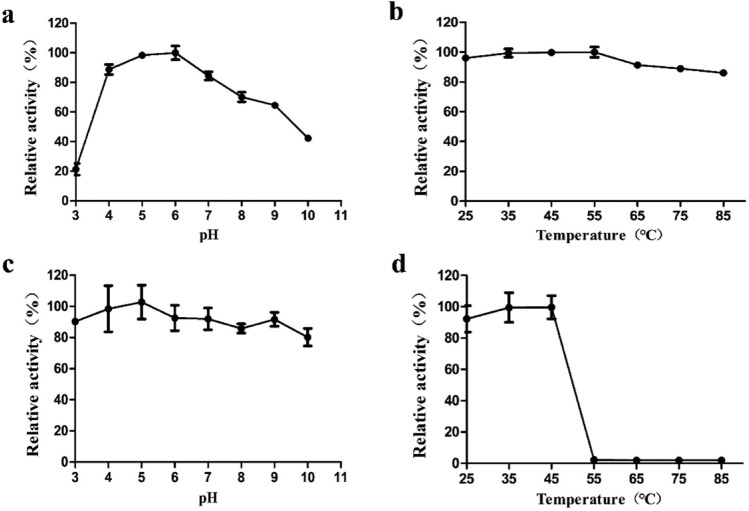

Using KGM as the substrate, PpGluB exhibited the most activity at pH 4.0 to 7.0 (retaining > 80% of its maximal activity) and had an optimum pH activity at pH 5.0–6.0 (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, PpGluB showed highly pH stability over a very broad pH range (retaining > 80% activity from pH 3.0 to 10.0 compared to untreated PpGluB) after being incubated at 4 °C for 24 h (Fig. 3c). The optimal temperature for PpGluB was 45–55 °C (Fig. 3b). Thermal stability analysis demonstrated that approximately 90% of initial activity could be retained below 45 °C (Fig. 3d), which suggested that PpGluB was relatively more sensitive towards high temperature. We speculated that there might exists a change in the conformation of the protein under high temperature, which inhibited its catalytic amino acid activity, thereby reduced the enzyme activity. These results were similar to previous studies reported that the optimal pH and temperature of many glucanase of the GH5 family are 4.0–10.0 and 40–60 °C. For instance, Cel5B from Paenibacillus polymxa GS01 has an optimum pH of 6.0 and a temperature of 50 °C (Cho et al. 2008).

Fig. 3.

Enzymatic properties of PpGluB. a The optimal pH of PpGluB. Activity at pH 6.0 was taken as 100%. b The optimal temperature of PpGluB. Activity at 55 °C was taken as 100%. c The pH stability of PpGluB. We performed pH stability at different pH ranging from 3.0 to 10.0 at 4 °C for 24 h. d The thermostability of PpGluB. Thermostability was measured at different temperatures ranging from 25 to 85 °C. Each value represented the mean of three replicates ± standard deviation

The impact of various metal ions and chemical reagents on PpGluB activity is shown in Table 3. The activity of PpGluB in presence of K+, Mg2+, Fe2+, Zn2+, Ba2+, Co2+ and Ca2+ at a concentration of 1 mM was similar to the control but was significantly inhibited by the presence of Cu2+, Mn2+, Fe3+ and SDS. The kinetic constants Km and Vmax for PpGluB were 12.71 mg/mL and 714.29 μmol/min/mg, respectively.

Table 3.

Effect of metal ions and chemical reagents on the hydrolytic activity of PpGluB

| Reagentsa | Relative activity (% ± SD)b |

|---|---|

| Control | 100 |

| K+ | 92 ± 2.3 |

| Mg2+ | 96 ± 6.4 |

| Fe2+ | 95 ± 4.4 |

| Zn2+ | 90 ± 2.6 |

| Cu2+ | 42 ± 4.3 |

| Mn2+ | 55 ± 2.8 |

| Ba2+ | 94 ± 2.1 |

| Co2+ | 107 ± 5.4 |

| Ca2+ | 92 ± 5.2 |

| Fe3+ | 51 ± 14 |

| EDTA | 72 ± 4.9 |

| SDS | 20 ± 11 |

aThe impact of 1 mM metal ions and chemical agents on enzymatic activities of PpGluB

bThe activity measured of PpGluB was performed in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) using KGM as the substrates (0.5%, w/v), and then incubated at 45 °C for 10 min

Analysis of hydrolysis products of PpGluB

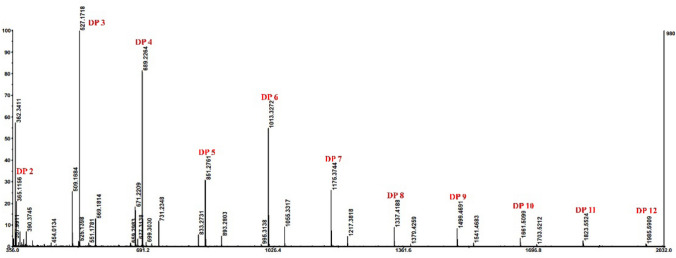

The hydrolyzed products of KGM by PpGluB were analyzed by MALDI-TOF–MS. The results indicated that a series of oligosaccharides with different degrees of polymerisation (DPs) were observed (Fig. 4). In the positive mode, the mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) of the DPs to the products were mainly calculated as 2 (365 m/z), 3 (527 m/z), 4 (689 m/z), 5 (851 m/z), 6 (1013 m/z), 7 (1175 m/z), 8 (1337 m/z), 9 (1499 m/z), 10 (1661 m/z), 11 (1823 m/z) and 12 (1985 m/z) from the ion peak [DPx 2–12 + Na]+ (x = 2–12) type. According to the product distribution pattern and substrate specificity, PpGluB was confirmed to have glucomannanase functionality. The activity of PpGluB (39.29 U/mg) was relatively low compared to that of glucanase (PpGluA) (289 U/mg) derived from the same strain Paenibacillus polymyxa (Li et al. 2020) and glucanase (Cel9C) (57 U/mg) from Clostridium josui (Ning et al. 2015) for glucomannan; and its activity is relatively higher than endo-β-1,4-glucanase (CelL) (2.5 U/mg) from Cellulosimicrobium funkei (Kim et al. 2016). Although the activity of PpGluB is not high, it can specifically degrade KGM to produce oligosaccharides, which is conducive to the separation of glucomannan oligosaccharides from the degradation of crude resources. The results of hydrolysis activity and MALDI-TOF–MS analysis showed that PpGluB is able to readily effectively degrade KGM into a series of glucomannan oligosaccharides (DP 2–12), which is a typical degradation mode of endoglucanase. The hydrolysis pattern of PpGluB is similar to most GH5-derived endo-β-1,4-glucanase or cellulase. In instance, the oligosaccharides resulting from EG (purified a crude cellulase preparation from Trichoderma viride) degrade to a large DP range (DP > 15) (Albrecht et al. 2011); endo-β-1,4-glucanase PpGluA from Paenibacillus polymyxa can degrade KGM to produce oligosaccharides with DP 2–9 (Li et al. 2020).

Fig. 4.

Hydrolytic analysis of PpGluB degradation of KGM. MALDI-TOF–MS analysis of products generated by PpGluB degradation of KGM. The mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) 365 m/z, 527 m/z, 689 m/z, 851 m/z, 1013 m/z, 1175 m/z, 1337 m/z, 1499 m/z, 1661 m/z, 1823 m/z and 1985 m/z represent the degree of polymerization of konjac glucomannan oligosaccharides 2–12, respectively

Studies have shown that KGM oligosaccharides have a variety of biological activities and are considered a valuable functional active substances (Zeng et al. 2018). Al-Ghazzewi et al. (2007) and Al-Ghazzewi and Tester (2012) confirmed that the hydrolysate of KGM has the activity to promote the growth of lactic acid bacteria. Liu et al. (2019) suggested that KGM oligosaccharide could be considered as a functional food material for regulating intestinal function and relieving constipation. Zeng et al. (2018) indicated that besides promoting the growth of probiotics and the production of short chain fatty acids, KGM oligosaccharide also has activities, such as promoting the immunoregulation of macrophages, increasing the glucose content in the blood, and alleviating physical fatigue. Therefore, KGOS can be used as a potential material for the development of functional foods.

In silico analysis of the mechanism of PpGluB degradation

Homology modeling indicated that PpGluB is a multi-domain protein including an N-terminal catalytic module of GH5 family (AA 1–344), a C-terminal CBM46 domain (AA 442–545), and an immunoglobulin (Ig)-like module (AA 345–441) in between (Fig. 5a). The N-terminal GH5 domain of PpGluB is similar to other members of the GH5 family, adopted a typical TIM-barrel (β/α)8 architecture that interconnected by loops and three short α helices. The active pocket of PpGluB is a narrow and deep V-shaped cleft that runs through the entire GH5 catalytic domain and is located at the top of the β-barrel. The GH5 family is usually linked to CBM of different families, thus exhibiting ligand specificity that reflects the substrate specificity of the relevant catalytic module. Generally, CBM enhances the activity of its additional catalytic modules by promoting the close interaction between the relevant catalytic domain and its target substrate (Venditto et al. 2015). However, CBM is usually structurally independent of the related catalytic domain, and does not necessarily promote the binding and activity of the enzyme to the substrate. Therefore, the influence of CBM on the catalytic domain is not absolute, and specific analysis needs to be carried out according to the structure of the enzyme. It has been reports that lack of CBM does not affect enzyme activity (Kern et al. 2013; Prates et al. 2013), but the activity of most enzymes depends on the presence of CBM (Boraston et al. 2004; Venditto et al. 2015). Venditto et al. (2015) reported that synergistic interactions between the GH5_4 catalytic domain and CBM46 of BhCel5B (55% sequence identity to PpGluB) play a critical role in glucan binding. The data from Liberato et al. (2016) indicate that the catalytic activity of cellulase BlCel5B (32% sequence identity to PpGluB) is entirely dependent on its two ancillary modules (Ig-like module and CBM46). The CBM46 domain of PpGluB shows the classic β-sandwich jelly roll fold, consisting of two β-sheets (containing four antiparallel β-strands) and a small helix for attachment. Based on the structure and sequence alignment of PpGluB, residue Trp483 may constitute a CBM ligand binding site and play a role in ligand recognition. The Ig-like module of PpGluB consists of two β-sheets, which are arranged around the hydrophobic core in a typical β-sandwich pattern.

The predicted substrate docking structure and catalytic apparatus show that PpGluB contains 6 glucan subsites extending from − 3 to + 3 (Fig. 5c). Two residues Glu156 and Glu278 correspond to the catalytic acid–base and nucleophile, respectively, and are located between the − 1 and + 1 subsites (Fig. 5c). As with other GH5 family hydrolases, these two residues are located at the ends of β-strands 4 and 7. According to the substrate docking structure and previous reports (Liberato et al. 2016), there are multiple conserved residues in PpGluB that interact with the substrate (Fig. 5c). At the − 3 subsite, Trp44 binds glucose units to establish a stacking interaction, and Asn32 makes polar contact with glycosyl groups. At the − 2 subsite, Trp114 side chain can hydrophobically interact with the glycosyl of the main chain, and Asp285 participating in hydrogen bonding interactions. At the − 1 subsite, the glycosyl group at this site is the most stable, with multiple residues (Asn155, Glu156, His231 and Tyr233) participating in hydrogen bonding interactions. And, Glu296 forms hydrogen bonding interactions with Tyr233 and Arg66. At the + 1 subsite, Leu282 forms a hydrophobic interaction with a glycosyl group. At the + 2 subsite, Trp236 plays a major role in substrate recognition. At the + 3 subsite, no conserved residues with significant interactions were found. This may be due to the fact that PpGluB covers multiple conformations from the closed CBM46/GH5 state to the extended CBM46/GH5 state. Based on the results of crystallography, computer simulation, and SAXS structure, Dorival et al. (2018), Liberato et al. (2016) and Venditto et al. (2015) proposed a binding mechanism of multi-domain enzymes and substrates. They thought that when CBM46 and GH5 were turned on, the substrate might reach the active site, and CBM46 was capped on GH5. After hydrolysis, the reaction product is released. Among them, the large-scale movements of CBM46 and Ig-like domains mediate conformational selection and final induction fit regulation, allowing substrates to reach active pockets and promote hydrolysis.

Conclusion

In the present study, a recombinant glucomannanase PpGluB was obtained from a KGM degradation strains Paenibacillus polymyxa 3–3 and heterologously expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). The recombinant enzyme has an optimal temperature is 45–55 °C and is stable at pH range 4.0–7.0. Moreover, PpGluB shows high activity and the specific degradation to KGM, and the hydrolytic products are identified as KGM oligomers with DPs of 2–12. The current characteristics indicated that PpGluB has great potential for the specific degradation of KGM to produce KGM oligosaccharides.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Key Laboratory of Se-enriched Products Development and Quality Control, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs/National Local Joint Engineering Laboratory of Se enriched Food Development (Se-2018A02, Se-2020C02); China Se-enriched Industry Research Institute Se-enriched Special 236 Plan Project (2019QCY-2.2); National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFD0200900) Subject 2 (2017YFD0200902). Dr. Heng Yin was supported by Liaoning Revitalization Talents Program, China (XLYC1807041).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. HY and JL designed the outline of the article. The first draft of the manuscript was written by KL and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. CJ, HT and JL searched the literature and related information. QL, XZ, DT and YX provided scientific feedback and critical comments to revise the content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Key Laboratory of Se-enriched Products Development and Quality Control, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs/National Local Joint Engineering Laboratory of Se enriched Food Development (Se-2018A02, Se-2020C02); China Se-enriched Industry Research Institute Se-enriched Special 236 Plan Project (2019QCY-2.2); National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFD0200900) Subject 2 (2017YFD0200902). Dr. Heng Yin was suppoted by Liaoning Revitalization Talents Program, China (XLYC1807041).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This study did not include any human subjects and animal experiments.

Consent to participate

All authors declare to participate in the article.

Consent for publication

All authors declare that they agreed to publish the article.

Contributor Information

Jianguo Li, Email: akljg@qq.com.

Heng Yin, Email: yinheng@dicp.ac.cn.

References

- Akesowan A. Optimization of textural properties of Konjac gels formed with κ-carrageenan or xanthan and xylitol as ingredients in jelly drink processing. J Food Process Preserv. 2015;39:1735–1743. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.12405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht S, van Muiswinkel GCJ, Xu JQ, Schols HA, Voragen AGJ, Gruppen H. Enzymatic production and characterization of Konjac glucomannan oligosaccharides. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:12658–12666. doi: 10.1021/jf203091h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghazzewi FH, Tester RF. Efficacy of cellulase and mannanase hydrolysates of konjac glucomannan to promote the growth of lactic acid bacteria. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:2394–2396. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghazzewi FH, Khanna S, Tester RF, Piggott J. The potential use of hydrolysed konjac glucomannan as a prebiotic. J Sci Food Agric. 2007;87:1758–1766. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behera SS, Ray RC. Konjac glucomannan, a promising polysaccharide of Amorphophallus konjac K. Koch in health care. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;92:942–956. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boraston AB, Bolam DN, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. Carbohydrate-binding modules: fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem J. 2004;382:769–781. doi: 10.1042/bj20040892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KM, et al. Cloning of two cellulase genes from endophytic Paenibacillus polymyxa GS01 and comparison with cel44C-man26A. J Basic Microbiol. 2008;48:464–472. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200700281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly ML, Lovegrove JA, Tuohy KM. Konjac glucomannan hydrolysate beneficially modulates bacterial composition and activity within the faecal microbiota. J Funct Foods. 2010;2:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2010.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorival J, et al. The laterally acquired GH5 ZgEngA(GH5_4) from the marine bacterium Zobellia galactanivorans is dedicated to hemicellulose hydrolysis. Biochem J. 2018;475:3609–3628. doi: 10.1042/Bcj20180486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Li J, Chen J, Li B. Effect of degree of deacetylation on physicochemical and gelation properties of konjac glucomannan. Food Res Int. 2012;46:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang WX, Wu PW. Variations of konjac glucomannan (KGM) from Amorphophallus konjac and its refined powder in China. Food Hydrocolloids. 2004;18:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0268-005x(03)00044-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B, Callebaut I, Fabrega S, Lehn P, Mornon JP, Davies G. Conserved catalytic machinery and the prediction of a common fold for several families of glycosyl hydrolases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7090–7094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, et al. Partial removal of acetyl groups in konjac glucomannan significantly improved the rheological properties and texture of konjac glucomannan and κ-carrageenan blends. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;123:1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Takahashi R, Kobayashi S, Kawase T, Nishinari K. Gelation behavior of native and acetylated konjac glucomannan. Biomacromol. 2002;3:1296–1303. doi: 10.1021/bm0255995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian W, Chen Y-H, Wang L, Tu L, Xiong H, Sun Y-M. Preparation and cellular protection against oxidation of Konjac oligosaccharides obtained by combination of γ-irradiation and enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Res Int. 2018;107:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Wei Y, Li D, Li L, Chai P, Kusakabe I. High-level production, purification and characterization of a thermostable beta-mannanase from the newly isolated Bacillus subtilis WY34. Carbohyd Polym. 2006;66:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.02.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Colmenero F, Cofrades S, Herrero AM, Fernandez-Martin F, Rodriguez-Salas L, Ruiz-Capillas C. Konjac gel fat analogue for use in meat products: comparison with pork fats. Food Hydrocolloids. 2012;26:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, Mei T, Wang Y, Xu W, Li J, Zhou B, Li B. Synergistic degradation of konjac glucomannan by alkaline and thermal method. Carbohyd Polym. 2014;99:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern M, et al. Structural characterization of a unique marine animal family 7 cellobiohydrolase suggests a mechanism of cellulase salt tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:10189–10194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301502110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DY, et al. Genetic and functional characterization of an extracellular modular GH6 endo-beta-1,4-glucanase from an earthworm symbiont, Cellulosimicrobium funkei HY-13 Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. Int J General Mol Microbiol. 2016;109:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10482-015-0604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-l, Deng R-h, Chen N, Pan J, Pang J. Review of konjac glucomannan: isolation, structure, chain conformation and bioactivities. J Single Mol Res. 2013;1:7. doi: 10.12966/jsmr.07.03.2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Chen W, Wang W, Tan H, Li S, Yin H. Effective degradation of curdlan powder by a novel endo-beta-1 -> 3-glucanase. Carbohyd Polym. 2018;201:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, et al. Preparation and antitumor activity of selenium-modified glucomannan oligosaccharides. J Funct Foods. 2020;65:103731. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liberato MV, et al. Molecular characterization of a family 5 glycoside hydrolase suggests an induced-fit enzymatic mechanism. Sci Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep23473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XY, Chen S, Yan QJ, Li YX, Jiang ZQ. Effect of Konjac mannan oligosaccharides on diphenoxylate-induced constipation in mice. J Funct Foods. 2019;57:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.04.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V, Ramulu HG, Drula E, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D490–D495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelson A, Maaheimo H, Hakala TK. Hydrolysis of konjac glucomannan by Trichoderma reesei mannanase and endoglucanases Cel7B and Cel5A for the production of glucomannooligosaccharides. Carbohydr Res. 2013;372:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen QA, Cho EJ, Lee D-S, Bae H-J. Development of an advanced integrative process to create valuable biosugars including manno-oligosaccharides and mannose from spent coffee grounds. Bioresour Technol. 2019;272:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Y, Chuang S, Chen X, Kazuo S, Wang D, Chang Y, Tang X. Expression of a glucanase gene cel9C from Clostridium josui and the activity of its recombinant enzyme. J Anhui Agric Univ. 2015;42:910–914. [Google Scholar]

- Nishinari K, Takahashi R. Interaction in polysaccharide solutions and gels. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;8:396–400. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0294(03)00099-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prates ET, et al. X-ray structure and molecular dynamics simulations of endoglucanase 3 from Trichoderma harzianum: structural organization and substrate recognition by endoglucanases that lack cellulose binding module. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester R, Al-Ghazzewi F. Glucomannans and nutrition. Food Hydrocolloids. 2017;68:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tuntrakool P, Keawsompong S. Kinetic properties analysis of beta-mannanase from Klebsiella oxytoca KUB-CW2–3 expressed in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2018;146:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venditto I, et al. Family 46 carbohydrate-binding modules contribute to the enzymatic hydrolysis of xyloglucan and beta-1,3–1,4-glucans through distinct mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:10572–10586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.637827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb B, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Bioinf. 2016;54:5.6.1–5.6.37. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia W, et al. A novel glycoside hydrolase family 113 endo-beta-1,4-mannanase from Alicyclobacillus sp. strain a4 and insight into the substrate recognition and catalytic mechanism of this family. Appl Environ Microb. 2016;82:2718–2727. doi: 10.1128/Aem.04071-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Zhang JG, Zhang Y, Men Y, Zhang B, Sun YX. Prebiotic, immunomodulating, and antifatigue effects of konjac oligosaccharide. J Food Sci. 2018;83:3110–3117. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YL, et al. Biochemical and structural characterization of the intracellular mannanase AaManA of Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius reveals a novel glycoside hydrolase family belonging to clan GH-A. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31551–31558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, et al. Purification and functional characterization of endo-beta-mannanase MAN5 and its application in oligosaccharide production from konjac flour. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;83:865–873. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Li Z, Wang Y, Xue Y, Xue C. Effects of konjac glucomannan on heat-induced changes of physicochemical and structural properties of surimi gels. Food Res Int. 2016;83:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Cao H, Hou M, Nirasawa S, Tatsumi E, Foster TJ, Cheng Y. Effect of konjac glucomannan on physical and sensory properties of noodles made from low-protein wheat flour. Food Res Int. 2013;51:879–885. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, et al. A lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase from Myceliophthora thermophila and its synergism with cellobiohydrolases in cellulose hydrolysis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;139:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, et al. A recombinant beta-mannanase from Thermoanaerobacterium aotearoense scut27: biochemical characterization and its thermostability improvement. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68:818–825. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]