Abstract

A marked 120 My gap in the fossil record of vampire squids separates the only extant species (Vampyroteuthis infernalis) from its Early Cretaceous, morphologically-similar ancestors. While the extant species possesses unique physiological adaptations to bathyal environments with low oxygen concentrations, Mesozoic vampyromorphs inhabited epicontinental shelves. However, the timing of their retreat towards bathyal and oxygen-depleted habitats is poorly documented. Here, we document a first record of a post-Mesozoic vampire squid from the Oligocene of the Central Paratethys represented by a vampyromorph gladius. We assign Necroteuthis hungarica to the family Vampyroteuthidae that links Mesozoic loligosepiids with Recent Vampyroteuthis. Micropalaeontological, palaeoecological, and geochemical analyses demonstrate that Necroteuthis hungarica inhabited bathyal environments with bottom-water anoxia and high primary productivity in salinity-stratified Central Paratethys basins. Vampire squids were thus adapted to bathyal, oxygen-depleted habitats at least since the Oligocene. We suggest that the Cretaceous and the early Cenozoic OMZs triggered their deep-sea specialization.

Subject terms: Palaeontology, Evolutionary ecology

A new fossil of a vampire squid bridges a 120 million-year gap in their fossil record. Vampire squid today are adapted to low oxygen, deep sea environments and this new specimen provides evidence that the deep sea specialisation of vampire squid may have been triggered during the development of oxygen minimum zones in the oceans during the Cretaceous and Cenozoic.

Introduction

Oceanic anoxic events record fundamental changes in the structure and functioning of marine ecosystems. They are determined by global carbon-cycle perturbations, warming episodes, reduced ventilation, increased weathering, the acceleration of organic flux export to the seafloor, and/or the isolation of oceanic basins1,2. The biotic responses to hypoxic or anoxic conditions in the geological past varied from regional extinctions during oceanic anoxic events3–5 up to radiations in the wake of anoxia6–10 and to adaptations to extreme low-oxygen habitats in oxygen minimum zones (OMZs). Understanding the dynamic of these responses can be informative for predicting abundances and geographic distribution of marine species affected by present-day trends in deoxygenation driven by human activities. The Recent deep-sea vampire squid Vampyroteuthis infernalis11 that inhabits the OMZs in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans possesses extraordinary adaptations to low oxygen concentrations, including a low metabolic rate12,13 and a detritivorous trophic strategy14, in contrast to predatory strategies of most other cephalopods. Vampyroteuthis is characterized by a mosaic of characters of the superorders Decabrachia and Octobrachia (Octopodiformes or Vampyropoda in other terminologies), but morphological15 molecular16–18 and combined studies19,20 indicate that Vampyroteuthis belongs to the octobrachian lineage. However, it is unclear when species of the family Vampyroteuthidae evolved their unique adaptations as no Cenozoic species within the vampyromorph lineage were described until now. This gap indicates not only a major preservation bias (Lazarus effect), but also inhibits any inferences about the timing of deep-sea colonization by vampire squids. The Lazarus effect21 can either reflect a decline in the outcrop area of post-Cretaceous deep-sea oxygen-depleted habitats and/or a decline in geographic range or in total population size of vampire squids so that their preservation potential is reduced even when the outcrop area remains the same.

The succesive shift of cephalopods into deeper part of oceans tends to be explained with hypotheses that postulate exclusion from shallower habitats driven by higher biotic or abiotic pressures22,23. The first hypothesis suggested that coleoids in shallower waters were effectively outcompeted and colonized deeper environments with smaller biotic pressures (explaining survivory strategy in nautiloids). Some lineages were subsequently able to reinvade shallower waters22. The second hypothesis23 suggested that although coleoids inhabited both shallow and deep habitats, extinctions preferentially occurred in shallower environments, and the temporal shift in the preference for deeper habitats is simply indirectly driven by higher extinction rate in shallower environments. Hereby, we suggest that active specialization to deep-sea habitats with anoxic conditions indicate that bathymetric variability in origination rate is also important in explaining the long-term trends in the bathymetric distribution of octobrachians.

Soft part morphologies indicate that Mesozoic gladius-bearing coleoids belong, as the vampire squid, to the Octobrachia24,25. The suborder Loligosepiina that diverged during the Triassic from the precursors of the Octopoda26, represents the vampyromorph branch that led to the origin of vampire squids27. The last stratigraphic record of loligosepiids corresponds to the Lower Aptian (Lower Cretaceous). Therefore, the fossil gap between the Recent Vampyroteuthis and its Cretaceous ancestors is at least 120 My. However, here we argue that an enigmatic fossil described by Kretzoi28 as Necroteuthis hungarica from the Oligocene Tard Clay Formation of the Hungarian Paleogene Basin (HPB) belongs to this vampyromorph lineage and fills the gap in the fossil record. Kretzoi28 and subsequent authorities regarded the morphology as a squid gladius29, whereas other authors thought to have identified a sepiid cuttlebone30. This uncertainty is rooted in the fact that fossil gladii appear to be primarily mineralized. Only chemical analyses (or X-ray diffraction) are able to distinguish between aragonite (the main component of cuttlebones) and francolite (modification of apatite), which is today widely seen as the diagenetic product of an originally chitinous gladius. The chemical composition and thus the real systematic affinities of Necroteuthis remained controversial because the single holotype specimen was lost since Kretzoi’s first investigations. However, we rediscovered the holotype of N. hungarica in the collection of Hungarian Natural History Museum in 2019, and micro-computed tomography (μ-CT) and SEM investigation unambiguously demonstrate that the specimen does not correspond to a cuttlebone, but instead represents a gladius of an Oligocene octobrachian. Owing to a triangular median field flanked by well-developed hyperbolar zones, Necroteuthis is most likely affiliated to both extinct loligosepiids and extant Vampyroteuthis25,31. The completely preserved gladius does not suggest any long-distance transport, and the absence of predation and epibiont activities indicate short residence time in the floating phase or at the sediment–water interface.

Our goals are (1) to examine the gladius of N. hungarica using SEM, μ-CT, geochemical analyses, and comparative anatomy, allowing us to properly assign this species, (2) to reconstruct the Oligocene environments inhabited by this cephalopod, and (3) and to track the onshore–offshore shift of vampyromorphs to bathyal and oxygen-depleted conditions since the Early Jurassic to Recent. A geographically extensive oxygen-depleted ecosystem that was established during the initial Early Oligocene isolation of the Parathetys (with salinity stratification, coccolith blooms, and bottom-water anoxia also documented in the Austrian Molasse Basin and in the Outer Carpathians32,33) could have triggered the adaptation of this species to deeper portions of basins. This analysis allows us to assess whether the extant Vampyroteuthis migrated to the deep-sea associated with dysoxic/anoxic conditions only recently.

Results

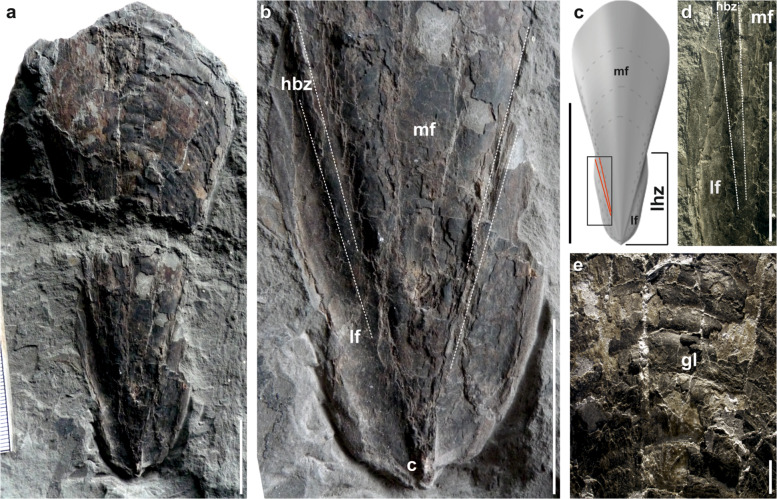

General gladius morphology

The almost complete gladius from Hungary (Supplementary Fig. 1), exposed in dorsal view, is 146 mm long and 60 mm wide (Fig. 1). It consists of a triangular median field (with a rounded anterior margin) laterally flanked by a pair of lateral fields, and a pair of hyperbolar zones (Fig. 1d). These characters are diagnostic for the suborder Loligosepiina26. The gladius is markedly flattened owing to the compaction. The undeformed gladius of Vampyroteuthis encircles the viscera for ~180° (ref. 34). Necroteuthis differs from loligosepiids in having shorter hyperbolar zones. The hyperbolar zone length of Necroteuthis is instead similar to Vampyroteuthis. Necroteuthis and Vampyroteuthis moreover share the unique existence of a posterior process that covers and extends the conus. The posterior part of the gladius shows markedly increased thickness, caused by the presence of compacted conus.

Fig. 1. Gladius of N. hungarica Kretzoi, 1942 (holotype—specimen no. M59/4672 Hungarian Natural History Museum).

a Nearly complete gladius, dorsal view, scale bar = 2 cm. b Detail of the apical part forming conus (c), mf median field, lf lateral fields, hbz hyperbolar zones, dashed lines mark the hyperbolar zones separating lateral fields from the median field, scale bar = 2 cm. c Reconstruction of the gladius, red lines demarcate hyperbolar zones, mf enlarged median field, lhf length of hyperbolar zones, scale bar = 10 cm, rectangle shows the postion of the d, scale bar = 2 cm. d Detail of the lateral field with hyperbolar zone and median field, scale bar = 2 cm. e Detail of the median field with marked concentric growth lines (gl).

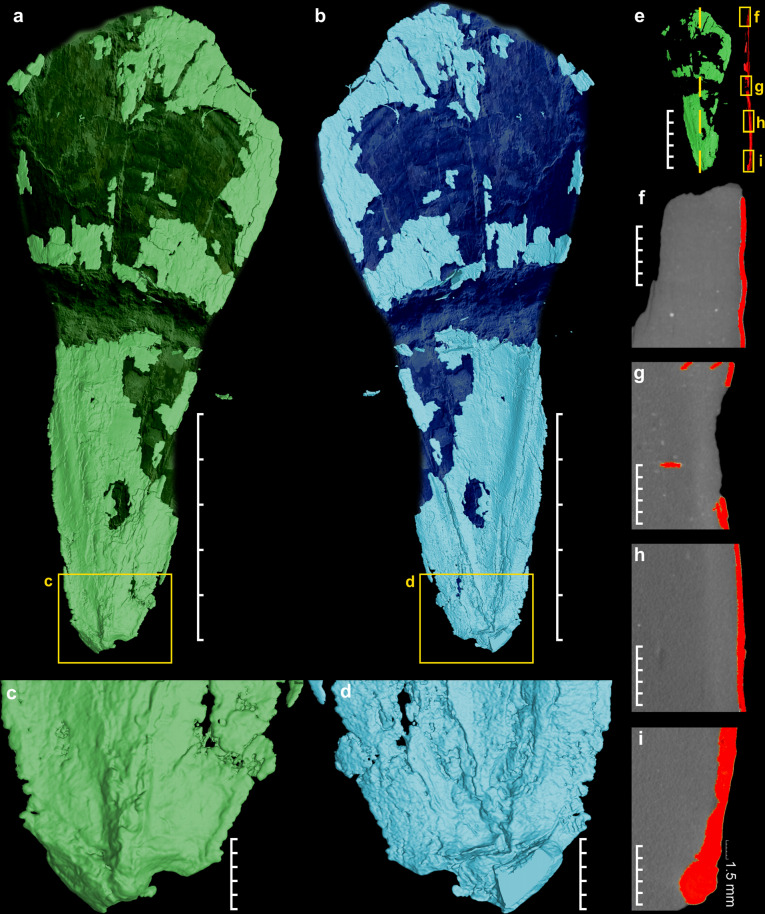

Micro-CT analysis

The μ-CT analysis (Fig. 2a–i) shows no evidence of a ventral chambered part. Therefore, the structure under investigation represents a gladius and not cuttlebone, in contrast to suggestions of previous authors30. The thickness of the gladius increases posteriorly (Fig. 2e–i). The maximum thickness (for ~2 mm) is located in the conus part (Fig. 2i). The ventral view demonstrates again the triangular and fattened character of the median field, the ventrally reduced conus part and the well-distinguished lateral fields.

Fig. 2. Micro-CT visualization of the gladius N. hungarica.

a Dorsal view. b Ventral view showing typical traingular median field (scale bars a, b = 5 cm). c detail of the posterior part forming conus, dorsal view. d detail of the posterior part lateral fields expansion, ventral view (scale bars c, d = 1 cm). e Position of lateral micro-CT sections (f–i), scale bar = 5 cm. f–i Lateral gladius sections (red color) documenting rise of thickness towards the apex (conical part), scale bars = 0.5 cm.

SEM analysis

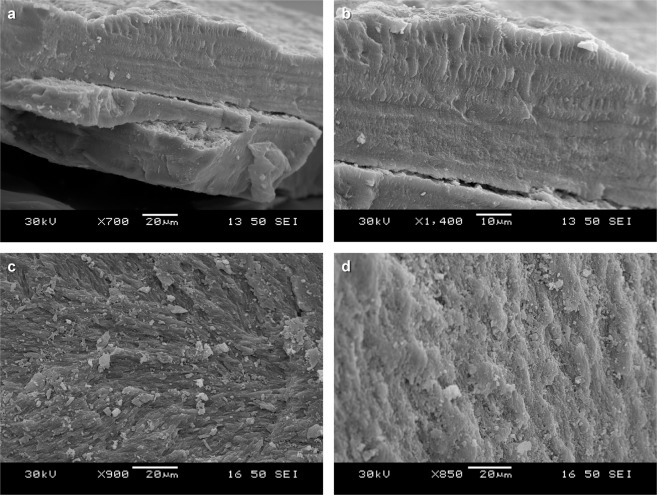

The gladius is multi-laminated (Fig. 3), typical for both decabrachian and octobrachian gladiuses25. Ultrastructurally, the laminae are composed of amorphous matter.

Fig. 3. SEM photos of the gladius N. hungarica.

a Complete thickness of the gladius in the median field area (central part of the gladius) with marked lamination, identical to the Recent gladius-bearing coleoids. b Detail of laminated gladius. c, d Details of the gladius surface. Note, the original β-chitin material has predominantly been replaced by (hydroxyl)apatite and gypsum during diagenetic and postdiagenetic processes.

FTIR

The chemical composition analysis based on the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Supplementary Fig. 2) corroborates the presence of organic material (spectrum E in Supplementary Fig. 2). The bands at 2963, 2930, and 2878 cm−1 are attributed to the antisymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of -CH3 and -CH2- functional groups. Some more diagnostic bands that were used for chitin identification, such as amide I and amide II bands at 1649 and 1544 cm−1 as reported in literature35, were not properly resolved. Gypsum (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B) and (hydroxyl)apatite (Supplementary Fig. 2C, D) were unambiguously identified in the samples.

Micropaleontological analysis

The sediment fraction 0.063–2 mm contains the framboidal pyrite and abundant skeletal remains, mainly fish bones and fragments of fish scales. Fish teeth, the organic-walled acritarchs Leiosphaeridia, Tasmanites, dinocysts, and small benthic foraminifera (genera Caucasina, Miliammina, Fursenkoina, and Bulimina) were present. Shells of foraminifers attain 44% of the microfossil assemblage, whereas organic-walled algae and acritarchs (Tasmanites with 80%, Wetzelielloideae with 9%, Leiosphaera) contribute with 56% (Supplementary Fig. 3). The benthic foraminiferal assemblage consists of nine taxa (Shannon index is 0.74, sample size = 68) and is strongly dominated by Caucasina oligocaenica (80.4%) and Fursenkoina subacuta (12.4%). The benthic foraminiferal oxygen index (BFOI) reaches −48 and indicates dysoxic conditions, with values of dissolved oxygen between 0.1–0.3 ml/l (ref. 36).

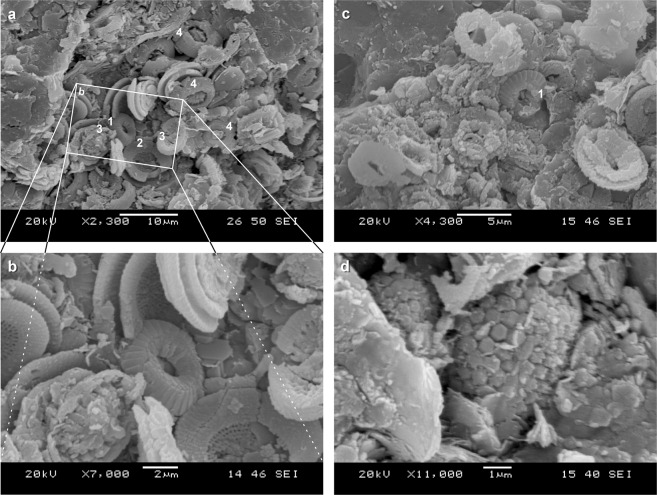

The calcareous nannoplankton assemblage is dominated by Reticulofenestra lockeri, Coccolithus pelagicus, and Reticulofenestra ornata. The assemblage ranges from extraordinary well-preserved coccoliths (Fig. 4) to coccoliths that are strongly degraded and overgrown by carbonate material. The diversity of nannoplankton assemblages is low to medium, with 17 species recorded in total and 6–11 species per sample, without any reworked taxa (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 4. SEM photos of calcareous nannofossils at Necroteuthis gladius level.

a–c Partly exposed nannoplankton accumulation with well-preserved coccoliths. a—general view. b Detail: a—C. pelagicus, b—R. umbilicus (probably part of coccosphaera), c—Pontosphaera enormis, and d—R. ornata. c Corroded and recrystallized undeterminable calcareous nannoplankton with exception of dissolution-resistant C. pelagicus (a). d Framboidal pyrite as indicator of bacterial activity in dysoxic sediment.

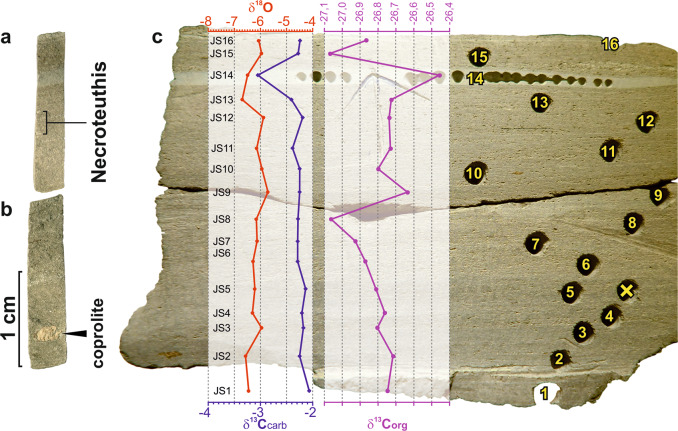

Stable isotope analysis

Sediment samples used for the stable isotope analysis (δ13C, δ18O) were drilled from a homogeneous, diagenetically unaltered component of sediment. Samples with bioclasts, signs of recrystallization, cements, and carbonate veins were excluded. The bulk carbonate samples show no significant correlation between δ13C and δ18O (r ~ 0.33) and are isotopically close to bulk samples from the Tard Clay Formation analyzed by ref. 37. High resolution sampling of 2.5-mm thick sediment increments from a 4 cm long transect surrounding the gladius showed negative values of δ13Ccarb (−3.05 to −2.08‰), and highly negative values of δ18O (−5.71 to −6.70‰; Fig. 5). In contrast to Necroteuthis-bearing sediment from the Tard Clay Fm., the δ13Ccarb and δ18Ocarb from cuttlefish Archaeosepia-bearing sediments of the overlying Kiscell Clay Fm. show less negative values (δ13Ccarb average = −0.78‰ and δ18Ocarb average = −2.78‰; Supplementary Table 2). The values of δ13Corg of the Necroteuthis-bearing sediment are relatively uniform, ranging between −27.07 and −26.46 (light gray, lamina sample no. 14, Fig. 5). The δ13Corg directly from the sediment yielding gladius (Fig. 5, samples 11–13) reaches −26.73‰ to −26.74‰ (Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 5. Transect trough the gladius-bearing sediment (scale bar = 1 cm) in relation to stable isotope data of the δ18Ocarb, δ13Ccarb, and δ13Corg.

a Upper part with position of the gladius level (equals to JS12, probe no. 12). b Lower part with a phosphatized coprolite. c Positions of probes used for geochemistry. Sample no. 14 (JS14) with markedly different both δ13C isotope values is represented by light-gray mudstone lamina.

Discussion

The gladius of Necroteuthis exhibits a mosaic of gladius features characteristic of Mesozoic loligosepiids and the extant genus Vampyroteuthis. We can exclude affinities of Necroteuthis to teudopseid or prototeuthid octobrachians because the former are characterized by a pointed median field and the latter by conspicously shorter hyperbolar zones17. Also, Necroteuthis does not show any similarities to the gladii of teuthid decabrachians. Teuthid gladii are more flimsy and markedly more slender than gladii of vampyromorphs.

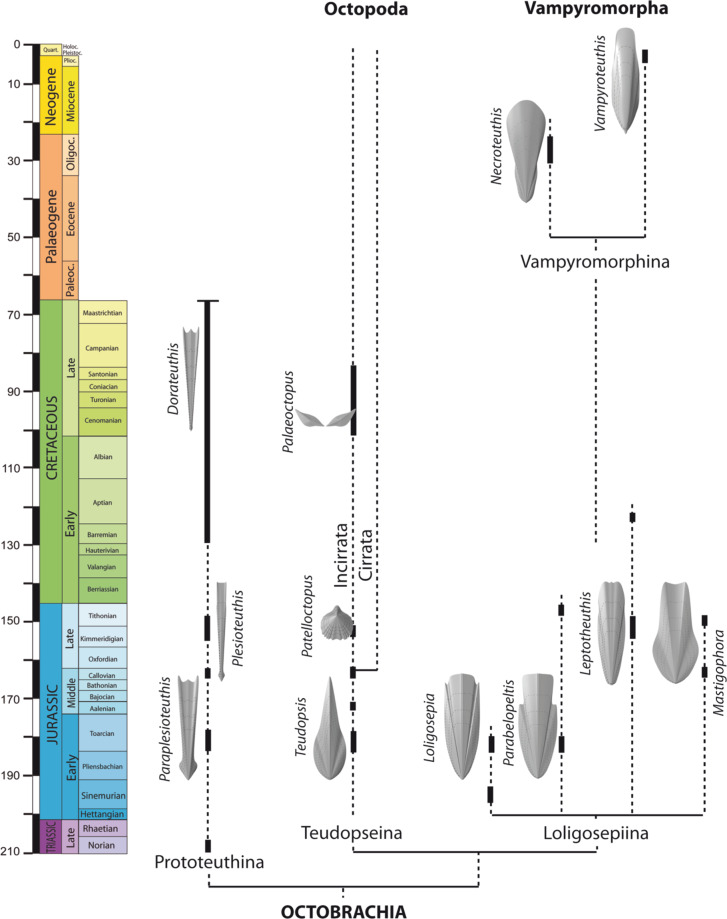

Both Necroteuthis and Vampyroteuthis share comparatively short hyperbolar zones that are weakly arcuated25,31. The suborder Loligosepiina by contrast is typified by long to very long well arcuated hyperbolar zones. Moreover, many loligosepiids exhibit a concave gladius margin rather than a distinctly convex one. Finally, the shared possession of a posterior process is unique. The latter mutualities suggest closer affinities of Necroteuthis to Vampyroteuthis than to loligosepiids. The assumed phylogenetic relationships are shown in the Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Phylogeny and stratigraphic distribution of the Octobrachia.

The presumed relationship between loligosepiid suborders Vampyromorphina and Loligosepiina is indicated. Note, not all genera within Loligosepiina are figured (after26, this paper).

The broad and weakly specific bands within the FTIR probably reflect a combination of the signal of the organic residue and the newly formed diagenetic minerals. The -CH3 and -CH2- functional groups suggest the presence of organic matter within the gladius, i.e., fragments of original chitin composition. Diagnostic bands (amide I and amide II bands at 1649 and 1544 cm−1) are overwhelmed by the signal from diagenetic minerals. We assume that the original chitinous matter was replaced by (hydroxyl)apatite as has also been suggested for mesozoic gladii38. This replacement is probably coupled with early diagenetic phosphatization as documented also by the presence of phosphatized coprolites (Fig. 5) in the surrounding sediment. The spectra document a mixture of fossilized organic matter with gypsum and (hydroxyl)apatite (Supplementary Fig. 2E).

The deposition of the Tard Clay Fm. took place in several hundreds of meters-deep HPB during the Early Oligocene39 as a relatively high rate of subsidence of the HPB coupled with an overall increase in eustatic sea level was not strongly compensated by sediment accumulation. Sedimentation of the Tard Clay Fm. occurred at ~400 m in the western part of the basin during the NP23 Zone (borehole Kiscell-1) and at even larger depths ~800 m in the eastern parts of the basin (borehole Cserepvaralja, based on detailed tectonical and sedimentological analyses)39. The water-column stratification with low-salinity and nutrient-rich surface layer and with oxygen depletion on the bottom in the HPB is indicated by benthic–pelagic gradients in δ18O, with highly negative δ18O values in planktonic foraminifers40 and in the bulk coccolith-derived carbonate (as observed here), by blooms of stress-tolerant nannoplankton assemblage that are typical of low salinity41, by weak levels of bioturbation and by low BFOI values in the whole Tard Clay Fm42. Both micropaleontological and geochemical data obtained from the surrounding sediment confirm this anoxic or even euxinic model for the deposition of the Tard Clay Fm., as previously interpreted by refs. 40,43.

First, blooms of calcareous nannoplankton dominated by the endemic Paratethys species R. ornata indicate very low-salinity and/or high nutrient levels in the surface layer and high abundance of R. lockeri indicates hyposaline waters44. Our SEM studies show that the carbonate sediment associated with Necroteuthis is partly represented by coccoliths. The extremely negative δ18O from bulk rock sample thus probably reflects the composition of surface water, in which coccoliths were calcified. These values are in accordance with δ18O of planktonic foraminifera40 that precipitated calcite in the same surface waters as calcareous nannoplankton. The difference in δ18O between co-occurring planktonic and benthic foraminifers40 suggest that the isotopic values were not modified by diagenesis and that the difference reflects a strong salinity stratification in the basin, with the prominent influx of freshwater and the formation of hyposaline surface waters. The water-column stratification was most likely driven by freshwater inflow, but poor ventilation was probably also induced by incipient isolation of Paratethys in the Early Oligocene32,33.

Second, the TOC values in the Tard Clay Fm. (~3%)37 indicate high primary productivity supported by blooms of algae (Tasmanites, Leiosphaera, and taxa of Wetzelielloideae) coupled with inefficient recycling of organic matter on the seafloor. High abundance of dinoflagellates of the genus Wetzeliella, high values of TOC, the lack of bioturbation, and negative BFOI values in the sediment sample with the vampire squid further corroborate that Necroteuthis was deposited during a period characterized by eutrophication in the surface layers and by anoxic conditions on the seafloor. Although previous authors40 found that the BFOI varying between −40 and 0 indicates suboxic conditions (with ~0.3–1.5 ml/l dissolved oxygen content in the bottom waters), our assemblage is strongly dominated by triserial foraminiferal forms (Caucasina, Bulimina, and Fursenkoina) belonging to deep infaunal species tolerating hypoxic conditions36,45, and BFOI is thus highly negative and attains −48. Such values indicate dissolved oxygen between 0.1 and 0.3 ml/l (ref. 36). Hypoxic conditions are also documented by very thin, densely porous shells of Caucasina and Fursenkoina (5–8 pores/µm2). Accumulations of organic-walled algae of the genus Tasmanites were reported from dysoxic environments46.

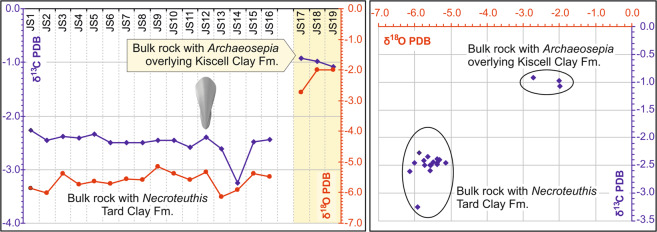

As the Recent vampire squid habitat is exclusively stenohaline (as other coleoid cephalopods), Necroteuthis very likely did not migrate to the upper surface layer with very low salinity. The stable isotope record from bulk rock samples from the overlying Kiscell Clay (spanning Rupelian/Chattian boundary) with mineralized cuttlebones of the sepiid Archaeosepia demonstrate that this cuttlefish lived in shallower and more oxygenated environments, as evidenced by abundant molluscs, decapod crustaceans, ostracods, brachiopods, and echinoderms47 and by the δ18Ocarb isotopic signal that indicates a weaker water-column stratification (Fig. 7). Therefore, Necroteuthis inhabited oxygen-depleted environments, whereas latter sepiids inhabited well-oxygenated environments. The expansion of other sepiids to deeper habitats was probably functionally constrained because the deepest records of few extant sepiid taxa reach 400–500 m (ref. 48) and functional analyses indicate that a gas-filled cuttlebone is subject to shell implosion at larger depths. The majority of sepiids therefore prefer waters shallower than 150 m and avoid greater depths48.

Fig. 7. Differences in the δ13Ccarb and δ18Ocarb isotopic signal from loligosepiid Necroteuthis-bearing sediment of the Tard Clay Fm.

Samples (JS1–JS16) and overlying, sepiid Archaeosepia-bearing sediment from the Kiscell Clay Fm. (samples JS17–JS19). More positive values of δ13Ccarb and δ18Ocarb represent more oxygened normal marine environment in younger strata. An accurate level of of Necroteuthis gladius is indicated by picture (JS12).

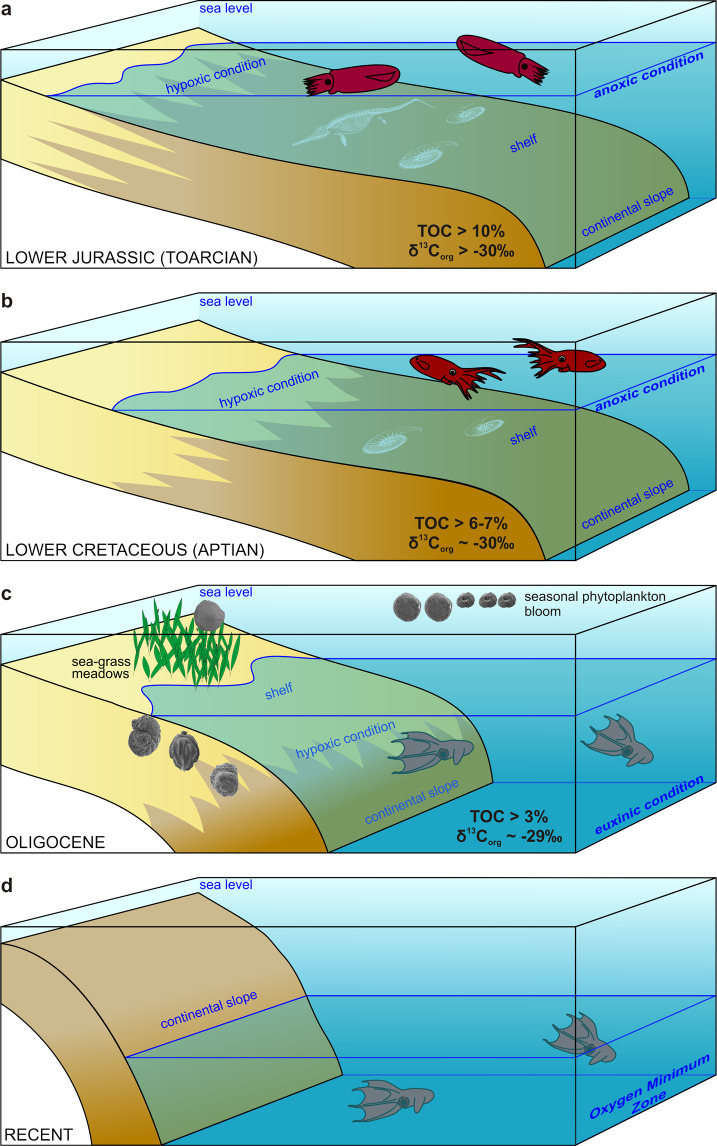

The offshore or bathyal retreat documented in the distribution of many lineages of marine invertebrates during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic is explained either by competitive and predatory exclusion from onshore habitats49, and/or by a push toward offshore as organic flux to deeper habitats increased during the Cretaceous and the Cenozoic50. On the one hand, although the roots of some present-day deep-sea invertebrate lineages, such as ophiomycetid ophiuroids or pterasterid and benthopectinid asteroids, can be traced back to the Jurassic51, the role of ocean anoxic events and the recurrent expansion of OMZs during oceanic anoxic events is mainly used to invoke repeated extinction risk disproportionately affecting deep-sea faunas adapted to normoxic conditions52. On the other hand, the OMZ can also trigger range expansions, speciations driven by opportunities with smaller predation pressure53, and can lead to endemism at macroevolutionary time scales54,55 and to habitat specialization allowed by persistent hypoxic conditions56 and/or by steep spatial gradients in oxygen concentrations57. However, morphological novelties based on cryptic specializations may be generated under anoxic conditions in both nearshore and offshore habitats58. Our compilation below documents (1) that the bathyal shift of vampyromorphs took place at least since the Oligocene or earlier during the Cretaceous and (2) that it might coincide with the development of the OMZ in the Central Paratethys. We thus invoke the role of OMZ as a trigger for habitat specialization of vampyromorphs. It is notable that the majority of Jurassic and Cretaceous loligosepiid records are associated with hypoxic or anoxic conditions (Fig. 8) that characterized poorly ventilated epicontinental seas of the NW European shelf (see below).

Fig. 8. Onshore–offshore shift of loligosepiid coleoids in relation to bathymetry and the oxygen minimum zone shift from shelf to deep-sea.

a Toarcian OAE event with loligosepiid occurrences associated with geographically extensive anoxic conditions on shelves. Geochemical data from ref. 59. b Aptian OAE1 event with loligosepiids associated with anoxic conditions on shelves. Geochemical data after refs. 66,67. c Oligocene habitat of N. hungarica in the Central Paratethys. Bathymetric conditions of the gladius record correspond to bathyal habitats with depth >400 m (ref. 39). Shallower, shelf environments were characterized by seagrass meadows with seagrass-associated foraminiferal assemblages. Geochemical data—this study and after ref. 37. d Recent living conditions of V. infernalis adapted to the OMZ at depth >600 m (ref. 14).

We propose the following geological timeline by documenting the occurrences of vampyromorphs in multiple Mesozoic Lagerstätten to explore the potential factors that may have driven vampyromorphs to adapt toward oxygen-depleted conditions in deep-sea environments.

Toarcian oceanic anoxic event

Jurassic loligosepiids show a relatively high diversity and abundance in black shales with exceptional preservation (i.e., Lagerstätten in southern Germany, Luxemburg, France, and UK) that were deposited on the NW European epicontinental shelves during the Toarcian Ocean Anoxic Event. Anoxic conditions were associated with warming, reduced ventilation, increased weathering on land, and increasing of freshwater influence, with the development of haline stratification in some basins59. It is difficult to assess whether the Early Jurassic loligosepiids (Loligosepia, Jeletzkyteuthis, Geopeltis, and Parabelopeltis) either lived within these anoxic basins (characterized by repeated but short-term reoxygenation events) or inhabited shallower, better-mixed normoxic environments. However, semi-enclosed oceanic basins in the Tethys and the Panthalassa were also characterized by anoxia and by the deposition of organic-rich sediments, but loligosepiids were not yet recorded from these deeper, bathyal environments. Therefore, loligosepiids were probably still limited to continental shelves during the Toarcian.

Callovian La Voulte-sur-Rhône

The Lower Callovian (Middle Jurassic) locality La Voulte-sur-Rhône yields unusual faunal assemblages. Coleoid cephalopods, including loligosepiids (Mastigophora, Vampyronassa, and Proteroctopus60) and prototeuthids (Romaniteuthis and Rhomboteuthis) represent 10% of macroinvertebrate assemblage preserved in organic-rich marls otherwise dominated by arthropods and echinoderms. The bottom-water conditions at the site of the soft-bottom deposition, with soft-tissue mineralization in the sediment zone with sulfate reduction61, were probably oxygen-depleted and temporarily anoxic, with limited bioturbation and mass mortalities documented by pavements of epibenthic bivalves (Bositra)62. As shown in ref. 63, photophilic encrusters are missing, invertebrates are encrusted by non-photozoans groups, such as serpulids, cyrtocrinid crinoids, sponges, and thecideid brachiopods, and the actualistic distribution of sea spiders, some crustaceans and sea stars indicate that the sedimentation took place on the outer shelf at ~200 m with dysphotic or aphotic conditions64. However, the co-occurrence of crustaceans with eyes adapted to photic conditions65 with groups with dysphotic or aphotic preferences indicate that the total assemblage represents a mixture of bathymetrically distinct habitats66, although any postmortem transport had to be minor and rapid as indicated by the excellent preservation of complete skeletons of fragile organisms. Fault-controlled escarpments with sponge communities not far from the site with the exceptional preservation64 indicate steep topographic graduents over short distances, and it is likely that even a limited short-distance migration to soft-bottom habitats in the wake of anoxic events or postmortem transport can explain the mixture of groups differing in ecological requirements in deeper environments. To summarize, coleoids in these environments still inhabited outer shelf close to the shelf/slope margin during the Callovian, and did not yet expand to deeper bathyal environments.

Kimmeridgian–Tithonian lithographic limestones

The Upper Jurassic records from lithographic limestones were deposited in semi-enclosed lagoons characterized by hypersalinity and partly dysoxic regime induced by bacterial activity at the bottom67. Although the cephalopod assemblages are predominantly allochtonous in these sediments, they clearly inhabited the surrounding epicontinental seas, and thus also do not record deep-sea conditions. Upper Jurassic loligosepiids are represented by genera Leptotheuthis, Doryanthes, and Bavaripeltis.

Aptian OAE1

The Mesozoic record of the Loligosepiina terminates in the Lower Aptian Oceanic Anoxic Event 1a (OAE1) at Heligoland68. The laminated, anoxic, and organic-rich “Fischschiefer” (“Töck”) originated under humid-warm regime with low salinity in upper parts of the water column69. The water depth of this habitat has been estimated between 50 and 150 m on the basis of belemnites69. The TOC values exceed >6–7% (refs. 69,70), extreme values to 10% (ref. 71), the lowest negative δ13Ccarb values exceed −9‰ (maximum peak), the lowest δ13Corg ~−30‰ (ref. 69), reflecting anoxic conditions and salinity driven stratification of the water column. The natural habitat of loligosepiids (Donovaniteuthis stuehmeri) is closely tied to oxygen-depleted conditions at the bottom, because low-salinity conditions in the upper parts of the water column are unfavorable for stenohaline fauna. There are no loligosepiid records from similar conditions represented by later OAE2 and OAE3 (Upper Cretaceous). This absence may indicate migration of vampyromorphs into the deep sea at the end of the Early Cretaceous. After this record (OAE1), vampyromorphs disappeared from the fossil record. Our new record from the Oligocene represents the first Cenozoic record of vampyromorphs.

Oligocene of the Central Paratethys

While the Mesozoic record of loligosepiids is limited to epicontinental shelves, the Oligocene record of Necroteuthis from the Central Paratethys is linked to bathyal environments reaching >400 m and bottom-water hypoxic/anoxic to euxinic conditions40. This occurrence thus demonstrates that the shift into bathyal oxygen-limited habitats occurred at least during the Oligocene. The deeper-water bathypelagic conditions probably provided opportunities for expansions of bathymetric ranges. Less predation and competitive pressure is typical of present-day oxygen-limited habitats with high abundance of food supply (especially on the edges of OMZs), where hypoxia-sensitive species are excluded55. However, the bathymetric shift of vampyromorph habitats can also be an important feature in the survivor strategy as it may have happened prior to the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. In contrast to ammonite lineages inhabiting continental shelves that were negatively affected by the end-Cretaceous mass extinction, this extinction did not affect deep-sea habitats. For example, some modern cephalopods whose ancestors survived this mass extinction event share a larger size of the eggs (expressed by larger protoconchs) relative to the victims of the mass extinction (with planktotrophic larvae), suggesting that the shift of vampyromorphs to larger water depths, associated with a shift towards production of larger eggs less dependent on planktonic food webs72–74, occurred prior to the K/T boundary.

Recent

The Recent Vampyroteuthis inhabits worldwide meso- and bathypelagic zones from 600 to ~1500 m (3300 m at maximum), with the highest abundance between 1260 and 1500 m (ref. 75). Its distribution is directly linked to the development of OMZ, which played a crucial role in Vampyroteuthis surviving as a refugium until recent times14.

As we have shown above, the Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous records are associated with hypoxic or anoxic conditions, indicating that vampyromorphs inhabited habitats close to anoxic/euxinic conditions already during the Mesozoic (Fig. 7). Therefore, if vampyromorphs shifted to deeper habitats prior to the K–Pg boundary, their adaptation to hypoxic conditions probably existed already in the Mesozoic, allowing survivorship of the loligosepiid lineage in deep-water refugia linked to the OMZ. The observation that loligosepiids do not occur at other Cretaceous Lagerstätten (e.g., Lebanon and Mexico) that are not directly associated with anoxic events is consistent with this hypothesis. The preservational potential of coleoid bodies in the fossil record is strongly limited by their fragile remains and by large amount of ammonia concentrated in their soft tissues, inhibiting precipitation of authigenic minerals76. However, coleoid gladii that represent a taphonomic control for loligosepiids occur in the Lower Turonian shelf sediments (Bohemian Cretaceous Basin) deposited under well-oxygenated conditions77. The absence of loliginid gladii suggests that loligosepiids may retreated from shallower environments already during the Cretaceous. Shallow-water sediments representing later multiple ocean anoxic events (OAE2 and OAE3) did not provide any loligosepiids records yet. Deep-water sediments of these periods are considerably rarer, therefore, it is possible that the extent of the preserved deep-sea sediments with exceptional preservation is still insufficient to detect this group78. Although it is possible that Mesozoic vampyromorphs were already adapted to low oxygen concentrations, the bathyal habitats of Oligocene Necroteuthis stand in sharp contrast to the shelf habitats of Jurassic and Cretaceous vampyromorphs. Necroteuthis inhabited bathyal habitats with high primary productivity and bottom-water anoxic conditions40,43. When the OMZs in the Central Paratethys basins formed during the Early Oligocene for the first time, the stratified and oxygen-depleted basins potentially generated new opportunities for the vampyromorph range expansion under stable low-oxygen levels.

Conclusions

The Oligocene Necroteuthis was a close relative of the extant deep-sea vampire squid Vampyroteuthis. Necroteuthis inhabited bathyal depths in the HPB characterized by stratified water-column and oxygen depletion on the bottom. This new insight shows that the Vampyromorpha shifted from shallow to deep water at least during the Oligocene. Adaptations to low concentrations of dissolved oxygen were probably already developed in Mesozoic loligosepiid vampyromorphs, as they inhabited epicontinental shelves with hypoxic conditions; however, the bathyal habitats of Oligocene Necroteuthis (~30 Mya) differs markedly from shelf habitats of Mesozoic vampyromorphs below the pycnocline, where competition and predation is typically reduced as hypoxia-sensitive species are excluded, but food supply tends to be high55.

The coleoid order Vampyromorpha survived major Meso- and Cenozoic oceanic crises, including oceanic anoxies, climatical, and sea-level changes, as well as the major extinction event at the K–Pg boundary. Owing to the scarce fossil record, we are currently unable to estimate the time of divergency between deep-sea Vampyromorphina and shallow-water Loligosepiina suborders. The Vampyromorphina thus consists of two genera, including the Recent genus Vampyroteuthis and the Oligocene genus Necroteuthis.

The vampyromorph evolutionary strategy reveals competitive advantage and survivory success during global biotic crises, as these niches were not affected by marked environmental changes.

Methods

Geological and historical settings

The gladius of Necroteuthis (No. M59/4672 Hungarian Natural History Museum) has been found in a clay pit near Budapest (“Ziegelfabrik von Csillaghegy, NNW—Budapest, Kisceller Ton”). The locality, i.e., the Csillaghegy Brickyard is also known as Péterhegy (or Péterhegy). The clay pit, was refilled and does not exist any more. Two litostratigraphical units were exposed in the clay pit79 (see Supplementary Information): (1) dark laminated Tard Clay Fm. deposited in a stagnant, restricted basin under anoxic conditions. The Tard Clay is not bioturbated and lacks benthic fauna. (2) The overlying dark gray, bioturbated Kiscell Clay Fm. was deposited under normal marine conditions with water depths between 200 and 1000 m estimated on the basis of benthic foraminifers80.

In the Csillaghegy clay pit, the two formations are exposed side by side, due to a tectonic contact (fault). Therefore, we assessed in detail whether the gladius comes from the Tard Clay Fm. or the Kiscell Clay Fm. Kretzoi28 assigned it to the Kiscell Clay Fm., but at that time the Tard Clay Fm. was not distinguished from the Kiscell Clay Fm. However, Kretzoi assigned the age of the Tard Clay Fm. (“Lattorfium oder unteres Rupelium”). Two new lines of evidence confirm that these specimens are derived from this formation. First, the matrix around the Necroteuthis specimen is represented by a laminated, hard, argilliferous rock, which is typical of the Tard Clay Fm. Second, co-occurrence of calcareous nannoplankton species R. ornate, Reticulofenestra umbilicus, and Discoaster nodifer indicates the NP22 Zone. This correlation is supported also by absence of Reticulofenestra abisecta that appears (first occurrence, FO) in the upper part of the NP23 zone. The repeated blooms of endemic Paratethys algae R. ornata took place during the zone interval NP22–NP24 (refs. 44,81). Therefore, the lithological features and calcareous nannoplankton clearly confirms that Necroteuthis specimen originates from the Tard Clay Fm. (NP22 to lower part of NP23 zones).

During the Early Oligocene, the system of the Middle European Paleogene basins was restricted what caused the closure of the seaways toward the weastern Tethys. This new paleogeographic situation was trigerred by orogeny in the South Alpine–Dinaridic belt, in combination with a third or second-order eustatic sea-level drop between 30 and 32 Ma (ref. 39). These changes led to the origin of the Central Paratethys, initially characterized by widespread deposition of organic-rich shales in stratified basins82 and by endemism of molluscs83. The Tard Clay Fm. was deposited during the Kiscellian under anoxic conditions in the HPB. The palaeobathymetric conditions were analyzed using geobasinal dynamic changes39 documenting palaeodepth reaching >400 m (i.e., bathyal or deep-sea in biological terminology78).

Micro-CT

μ-CT imaging was performed with phoenix v|tome|x L 240 device, developed by GE Sensing & Inspection Technologies. Investigated samples were analyzed by using 240 kV/320 W microfocus tube. Scanning parameters were set as follows. For Necroteuthis sample: voltage 200 kV, current 250 μA, projections 2500, average 3, skip 1, timing 500 ms, voxel size 80 μm, and 0.5 mm Cu filter. After the scanning process, 3D data sets were evaluated with VG Studio Max 2.2. For the address of storage space, see Supplementary Information (Supplementary Micro-CT imaging).

Fourier transform Infrared spectroscopy

The infrared spectra were recorded by micro-ATR technique on a Thermo Nicolet iN10 FTIR microscope, using Ge crystal in the 675–4000 cm−1 region (2 cm−1 resolution, Norton−Beer strong apodization, MCT/A detector). Standard ATR correction (Thermo Nicolet Omnic 9.2 software) was applied to the recorded spectra. Several miniature samples (<1 mm) of dark-colored fossilized material were analyzed by infrared spectroscopy using a micro-ATR technique. Reference spectra for gypsum and (hydroxyl)apatite were taken from the RRUFF online database of spectroscopic and chemical data of minerals84.

Stable isotope record

Stable C and O isotopes in carbonate fraction of clay sediments were analyzed on isotope-ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) MAT253, coupled with Kiel IV device for semiautomated carbonate preparation (ThermoScientific). A total of 40–100 micrograms of milled powder were loaded into borosilicate glass vials, evacuated, and digested in anhydrous phosphoric acid at 70 °C following method85. Yielded CO2 gas was cryogenically purified and introduced into the IRMS via dual-inlet interface. Isotope composition was measured against CO2 reference gas and raw values were calibrated using international reference material NBS18 and two working standards with δ13C = 5.014‰, +2.48‰, −9.30‰ and δ18O = −23.2‰, −2.40‰, −15.30‰, respectively. The values are reported as permil vs. PDB, precision of measurement is 0.02‰ for carbon and 0.04‰ for oxygen.

Stable carbon isotopes of organic matter were measured on mass spectrometer MAT253, coupled to elementar analyzer Flash2000 HT Plus (ThermoScientific). Residues after digestion in hydrochloric acid of ~900–1300 micrograms were wrapped into tin capsules and combusted in a stream of helium at 1000 °C in quartz tube packed with tungsten oxide and electrolytic copper. Purified CO2 gas was separated from other gases on capillary GC column (Poraplot Q, Agilent) and introduced into IRMS in continuous flow mode. Raw isotope ratios measured against CO2 reference gas were calibrated to PDB scale, using two international reference materials (USGS24 carbon, USGS41 glutamic acid) and two working standards, with δ13C values −16.05, +37.76, −39.79, and −25.60‰, respectively. All the values are reported in permil PDB, precision measured on standards is 0.11 permil. Standard deviation = 0.106‰.

SEM and imaging

The fossilized gladius was examined at the Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague by scanning electron microscope (SEM) JEOL-6380LV at 20, 25, and 30 kV and at ×1.7–10 k magnification. Microscopic gladius remains as well as the bulk rock fragment with Ca-nannofossils were coated with gold and investigated in the low and high vacuum modes. The macro-photo of Necroteuthis specimen was taken using the camera Canon EOS 600D. Photographs were improved using CorelDRAW X7 and Corel Photo-Paint X7 graphic softwares.

Microfossil investigation

Microfossils were collected and determined using Olympus SZ61 binocular stereoscopic microscope Olympus B750 and optical Zeiss Axiolab 5 microscope, and documented by SEM microscope JEOL-6380LV. Determination of foraminifers is in accordance with published methodics86. Paleoecological parameters were evaluated on the presence and dominance of taxa exhibiting special environmental significance36,46. The BFOI36 was determined to assess bottom-water concentrations of dissolved oxygen. The index is based on proportion of oxic, suboxic, and dysoxic indicator species of benthic foraminifera. The Kaiho’s classification36 of benthic foraminifera to these three groups was used. Because at least one oxic species was found, we used the following equation for counting of the BFOI in agrement with published data36:

Where: O—proportion of oxic species and D—proportion of dysoxic species. Values of the BFOI index can vary from −100 to +100, higher the values indicate higher oxygen concentration.

Taphonomic analysis of foraminiferal assemblages was performed following the concept of refs. 87,88. Beside the foraminifers, the organic-walled cysts and algae were counted in wash residuum. Calcareous nannoplankton was studied by both optic microscope (magnification 1000×, crossed and parallel nicols) and SEM. Slides for optic microscopy were prepared according to ref. 89.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the projects: PROGRES Q45 (M.K., K.H., M.M., and A.C.), Center for Geosphere Dynamics (UNCE/SCI/006—M.K., K.H., M.M., and A.C.), 20-05872 S (K.H.), 18-05935 S (K.H.), GAČR No. 20-10035 S (M.K. and M.M.), APVV 17-0555 (J.S., N.H., and A.T.), and VEGA 0169-19 (J.S., N.H., and A.T.).

Author contributions

M.K. and J.S. had initial idea to describe the material, investigation, conceptualization, and data interpretations. M.K., J.S., D.F., I.F., K.H., N.H., A.T., A.C., R.M., and J.Š. performed investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, with input of all authors. K.H. and N.H.: micropalaeontological analysis. A.C., R.M., and J.Š.: geochemical analysis. M.M.: visualization and SEM analysis. A.T.: proofread and corrected the entire text, data interpretations.

Data availability

The micro-computed tomography images generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the figshare repository: 10.6084/m9.figshare.13526024 (ref. 90). The Necroteuthis holotype which is the subject of the imaging is housed in the Hungarian Natural History Museum under item: No. M59/4672.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-021-01714-0.

References

- 1.Jenkyns HC. Geochemistry of oceanic anoxic events. Geochem. Geophy. Geosy. 2010;11:Q03004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gambacorta G, Bersezio R, Weissert H, Erba E. Onset and demise of Cretaceous oceanic anoxic events: The coupling of surface and bottom oceanic processes in two pelagic basins of the western Tethys. Paleoceanography. 2016;31:732–757. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palfy J, Smith PL. Synchrony between Early Jurassic extinction, oceanic anoxic event, and the Karoo–Ferrar flood basalt volcanism. Geology. 2000;28:747–750. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leckie RM, Bralower TJ, Cashman R. Oceanic anoxic events and plankton evolution: Biotic response to tectonic forcing during the mid‐Cretaceous. Paleoceanography. 2002;17:13-11–13-29. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erba E. Calcareous nannofossils and Mesozoic oceanic anoxic events. Mar. Micropaleontol. 2004;52:85–106. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erbacher JVJT, Thurow J. Influence of oceanic anoxic events on the evolution of mid-Cretaceous radiolaria in the North Atlantic and western Tethys. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1997;30:139–158. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harries PJ, Little CT. The early Toarcian (Early Jurassic) and the Cenomanian–Turonian (Late Cretaceous) mass extinctions: similarities and contrasts. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1999;154:39–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danise S, Twitchett RJ, Little CT. Environmental controls on Jurassic marine ecosystems during global warming. Geology. 2015;43:263–266. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dera G, Toumoulin A, De Baets K. Diversity and morphological evolution of Jurassic belemnites from South Germany. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2016;457:80–97. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rita P, Nätscher P, Duarte LV, Weis R, De Baets K. Mechanisms and drivers of belemnite body-size dynamics across the Pliensbachian–Toarcian crisis. Roy. Soc. Open Sci. 2019;6:190494. doi: 10.1098/rsos.190494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chun, C. Aus den Tiefen des Weltmeeres, 88 (ed. Fischer, G.) (Schilderungen von der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition, 1903).

- 12.Seibel BA, et al. Vampire blood: respiratory physiology of the vampire squid (Vampyromorpha: Cephalopoda) in relation to the oxygen minimum layer. Exp. Biol. Online. 1999;4:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoving HJT, Robison BH. Vampire squid: Detritivores in the oxygen minimum zone. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2012;279:4559–4567. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golikov AV, et al. The first global deep-sea stable isotope assessment reveals the unique trophic ecology of Vampire Squid Vampyroteuthis infernalis (Cephalopoda) Sci. Rep. 2019;9:19099. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55719-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young R, Vecchione M. Analysis of morphology to determine primary sister taxon relationships within coleoid cephalopods. Am. Malacol. Bull. 1996;12:91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strugnell J, et al. Whole mitochondrial genome of the Ram’s Horn Squid shines light on the phylogenetic position of the monotypic order Spirulida (Haeckel, 1896) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017;109:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez G, et al. Genus-level phylogeny of cephalopods using molecular markers: current status and problematic areas. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4331. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindgren AR, et al. A multi-gene phylogeny of Cephalopoda supports convergent morphological evolution in association with multiple habitat shifts in the marine environment. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012;12:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanner AR, et al. Molecular clocks indicate turnover and diversification of modern coleoid cephalopods during the Mesozoic marine revolution. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2017;284:20162818. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindgren AR, Giribet G, Nishiguchi MK. A combined approach to the phylogeny of Cephalopoda (Mollusca) Cladistics. 2004;20:454–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2004.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fara E. What are Lazarus taxa? Geol. J. 2001;36:291–303. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Packard A. Cephalopods and fish: the limits of convergence. Biol. Rev. 1972;47:241–307. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nixon, M. & Young, J. Z. The Brains and Lives of Cephalopods, 1–406 (Oxford University Press, 2003).

- 24.Kröger B, et al. Cephalopod origin and evolution. Bioessays. 2011;33:602–613. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuchs D. Part M, Chapter 9B: the gladius and gladius vestige in fossil Coleoidea. Treatise Online. 2016;83:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuchs D, et al. The Muensterelloidea: phylogeny and character evolution of Mesozoic stem octopods. Pap. Palaeontol. 2019;6:31–92. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuchs D, et al. The locomotion system of fossil Coleoidea (Cephalopoda) and its phylogenetic significance. Lethaia. 2016;49:433–454. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kretzoi M. Necroteuthis n.gen. (Ceph. Dibr. Necroteuthidae n.f.) aus dem Oligozän von Budapest und das System der Dibranchiata. F.öldt. K.özl. (Bp.) 1942;72:124–138. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donovan DT. Evolution of the dibranchiate Cephalopoda. Symp. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1977;38:15–48. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riegraf, W., Janssen, N., & Schmitt-Riegraf, C. A. in Fossilum Catalogus I. Animalia, Vol. 135 (ed. Westphal, F.), 1–512 (1998).

- 31.Fuchs D. Part M, Coleoidea, chapter 23G: systematic descriptions: octobrachia. Treatise Online. 2020;138:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz HM, Bechtel A, Sachsenhofer RF. The birth of the Paratethys during the Early Oligocene: from Tethys to an ancient Black Sea analogue? Glob. Planet. Change. 2005;49:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bojanowski MJ, et al. The Central Paratethys during Oligocene as an ancient counterpart of the present-day Black Sea: Unique records from the coccolith limestones. Mar. Geol. 2018;403:301–328. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bizikov, V. A. Evolution of the shell in Cephalopoda, 1–448 (VNIRO, 2008).

- 35.Weaver PG, et al. Characterization of organics consistent with β-Chitin preserved in the Late Eocene cuttlefish Mississaepia mississippiensis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaiho K. Benthic foraminiferal dissolved-oxygen index and dissolved-oxygen levels in the modern ocean. Geology. 1994;22:719–722. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bechtel A, et al. Facies evolution and stratigraphic correlation in the early Oligocene Tard clay of Hungary as revealed by maceral, biomarker and stable isotope composition. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2012;35:55–74. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donovan DT. Part M., Chapter 9C: composition and structure of gladii in fossil Coleoidea. Treatise Online. 2016;75:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagymarosy A, et al. The effect of the relative sea-level changes in the north Hungarian Paleogene Basin. Geol. Soc. Greece Spec. Publ. 1995;4:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozsvárt P, et al. The Eocene-Oligocene climate transition in the Central Paratethys. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2016;459:471–487. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nyerges A, Kocsis TÁ, Pálfy J. Changes in calcareous nannoplankton assemblages around the Eocene-Oligocene climate transition in the Hungarian Palaeogene Basin (Central Paratethys) Hist. Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1080/08912963.2019.1705295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozsvárt P. Middle and Late Eocene benthic foraminiferal fauna from the Hungarian Paleogene Basin: systematics and paleoecology. Geol. Pannonica Spec. Pap. 2007;2:1–129. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagymarosy A. Lower Oligocene nannoplankton in anoxic deposits of the central Paratethys. 8th International Nannoplankton Assoc. Conf., Bremen. J. Nannoplankton Res. 2000;22:128–129. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagymarosy, A. & Voronina, A. A. Calcareous nannoplankton from the Lower Maikopian beds (Early Oligocene, Union of Independent States). In Proc. 4thINA Conf. Prague 1991, Knihovnička ZPN14b (eds Hamršmíd, B. & Young, J.) 187–221 (Nannoplankton Research, 1992).

- 45.Murray, J. W. Ecology and Applications of Benthic Foraminifera, 1–426 (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- 46.Mørk A, Bromley RG. Ichnology of a marine regressive systems tract: the Middle Triassic of Svalbard. Polar Res. 2008;27:339–359. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Báldi, T. Mid-Tertiary Stratigraphy and Paleogeographic Evolution of Hungary, 1–201 (Akadémiai Kiadó, 1986).

- 48.Khromov DN. Distribution patterns in Sepiidae. Smithson. Contr. Zool. 1998;568:191–206. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sepkoski JJ., Jr A model of onshore-offshore change in faunal diversity. Paleobiology. 1991;17:68–77. doi: 10.1017/s0094837300010356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith AB, Stockley B. The geological history of deep-sea colonization by echinoids: roles of surface productivity and deep-water ventilation. P. Roy. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005;272:865–869. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thuy B, et al. First glimpse into Lower Jurassic deep-sea biodiversity: in situ diversification and resilience against extinction. P. Roy. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014;281:20132624. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobs DK, Lindberg DR. Oxygen and evolutionary patterns in the sea: onshore/offshore trends and recent recruitment of deep-sea faunas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:9396–9401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeidberg LD, Robison BH. Invasive range expansion by the Humboldt squid, Dosidicus gigas, in the eastern North Pacific. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12948–12950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702043104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rogers AD. The role of the oceanic oxygen minima in generating biodiversity in the deep sea. Deep Sea Res. Pt. II. 2000;47:119–148. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levin LA. Oxygen minimum zone benthos: adaptation and community response to hypoxia. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 2003;41:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Childress JJ, Seibel BA. Life at stable low oxygen levels: adaptations of animals to oceanic oxygen minimum layers. J. Exp. Biol. 1998;201:1223–1232. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gooday AJ, et al. Habitat heterogeneity and its influence on benthic biodiversity in oxygen minimum zones. Mar. Ecol. 2010;31:125–147. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wood R, Erwin DH. Innovation not recovery: dynamic redox promotes metazoan radiations. Biol. Rev. 2018;93:863–873. doi: 10.1111/brv.12375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hermoso M, Minoletti F, Pellenard P. Black shale deposition during Toarcian super‐greenhouse driven by sea level. Clim. 2013;9:2703–2712. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kruta I, et al. Proteroctopus ribeti in coleoid evolution. Paleontology. 2016;59:767–773. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilby PR, Briggs DE, Riou B. Mineralization of soft-bodied invertebrates in a Jurassic metalliferous deposit. Geology. 1996;24:847–850. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Etter, W. in Exceptional fossil preservation. A Unique View on the Evolution of Marine Life (eds Bottjer, D. J., Etter, W., Hagadorn, J. W. & Tang, C. M.) 293–305 (Columbia University Press, 2002).

- 63.Charbonnier S, Vannier J, Gaillard C, Bourseau J-P, Hantzpergue P. The La Voulte Lagerstätte (Callovian): Evidence for a deep water setting from sponge and crinoid communities. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007;250:216–236. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Charbonnier S, Audo D, Caze B, Biot V. The La Voulte-sur-Rhône Lagerstätte (Middle Jurassic, France) CR Palevol. 2014;13:369–381. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vannier J, Schoenemann B, Gillot B, S. Charbonnier S, Clarkson E. Exceptional preservation of eye structure in arthropod visual predators from the Middle Jurassic. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10320. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Audo D, et al. palaeoecology of Voulteryon parvulus (eucrustacea, polychelida) from the Middle Jurassic of La Voulte-sur-Rhône Fossil-Lagerstätte (France) Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41834-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Viohl, G. in Solnhofen. Ein Fenster in die Jurazeit. (eds Arratia, G., Schultze, H.-P., Tischlinger, H. & Viohl, G.) 56–62 (Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, 2015).

- 68.Engeser T, Reitner J. Teuthiden aus dem Unterapt (“Töck”) von Helgoland (Schleswig-Holstein, Norddeutschland) Pal. Z. 1985;59:245–260. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mutterlose J, Pauly S, Steuber T. Temperature controlled deposition of early Cretaceous (Barremian–early Aptian) black shales in an epicontinental sea. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2009;273:330–345. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heldt M, Mutterlose J, Berner U, Erbacher J. First high-resolution δ13C-records across black shales of the Early Aptian Oceanic Anoxic Event 1a within the mid-latitudes of northwest Europe (Germany, Lower Saxony Basin) Newsl. Stratigr. 2012;45:151–169. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bottini C, Mutterlose J. Integrated stratigraphy of Early Aptian black shalesin the Boreal Realm: calcareous nanofossil and stable isotope evidence forglobal and regional processes. Newsl. Stratigr. 2012;45:115–137. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Landman NH, et al. Ammonite extinction and nautilid survival at the end of the Cretaceous. Geology. 2014;42:707–710. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fuchs D, Laptikhovsky V, Nikolaeva S, Ippolitov A, Rogov M. Evolution of reproductive strategies in coleoid mollusks. Paleobiology. 2020;46:82–103. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tajika A, Nützel A, Klug C. The old and the new plankton: ecological replacement of associations of mollusc plankton and giant filter feeders after the Cretaceous? PeerJ. 2018;6:e4219. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lu CC, Clarke MR. Vertical distribution of cephalopods at 40°N, 53°N and 60°N at 20°W in the North Atlantic. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U.K. 1975;55:143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Clements T, Colleary C, De Baets K, Vinther J. Buoyancy mechanisms limit preservation of coleoid cephalopod soft tissues in Mesozoic Lagerstätten. Palaeontology. 2017;60:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Košťák M, Kohout O, Mazuch M, Čech S. An unusual occurrence of vascoceratid ammonites in the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin (Czech Republic) marks the lower Turonian boundary between the Boreal and Tethyan realms in central Europe. Cret. Res. 2020;108:104338. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oji, T. in Palaeobiology II (eds Briggs, D. E. G. & Crowther, P. R.) 444–447 (Blackwell Science Ltd, 2001).

- 79.Báldi, T. A. in Geológiai Kirándulások Magyarország Közepén (ed. Palotai, M.) 94–129 (Hantken Kiadó, 2010).

- 80.Tari G, et al. Paleogene retroarc flexural basin beneath the Neogene Pannonian Basin: a geodynamic model. Tectonophysics. 1993;226:433–455. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Švábenická L, et al. Biostratigraphy and paleoenvironmental changes on the transition from the Menilite to Krosno lithofacies (Western Carpathians, Czech Republic) Geol. Carpath. 2007;58:237–262. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kováč M, et al. Paleogene palaeogeography and basin evolution of the Western Carpathians, Northern Pannonian domain and adjoining areas. Glob. Planet. Change. 2016;140:9–27. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nevesskaja LA, et al. History of Paratethys. Ann. Inst. Géol. Hong. 1987;70:337–342. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lafuente, B., Downs, R. T., Yang, H. & Stone, N. in Highlights in Mineralogical Crystallography (eds Armbruster, T. & Danisi, R. M.) 1–30 (De Gruyter, 2015).

- 85.McCrea JM. On the isotopic chemistry of carbonates and a paleotemperature scale. J. Chem. Phys. 1950;18:849–857. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guiry, M. D. & Guiry, G. M. AlgaeBase (World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway, accessed May 18, 2020); https://www.algaebase.org.

- 87.Holcová K. Postmortem transport and resedimentation of foraminiferal tests: relations to cyclical changes of foraminiferal assemblages. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1999;145:157–182. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Folk RL. Nannobacteria and the formation of framboidal pyrite: Textural evidence. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2005;114:369–374. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zágoršek, K. et al. Bryozoan event from Middle Miocene (Early Badenian) lower neritic sediments from the locality Kralice nad Oslavou (Central Paratethys, Moravian part of the Carpathian Foredeep). Int. J. Earth. Sci. 97, 835–850 (2007).

- 90.Košťák, M. et al. Micro-computed tomography data supporting the manuscript: Fossil evidence for vampire squid inhabiting oxygen-depleted ocean zones since at least the Oligocene. figshare 10.6084/m9.figshare.13526024 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The micro-computed tomography images generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the figshare repository: 10.6084/m9.figshare.13526024 (ref. 90). The Necroteuthis holotype which is the subject of the imaging is housed in the Hungarian Natural History Museum under item: No. M59/4672.