Abstract

Suspension feeding is a key ecological strategy in modern oceans that provides a link between pelagic and benthic systems. Establishing when suspension feeding first became widespread is thus a crucial research area in ecology and evolution, with implications for understanding the origins of the modern marine biosphere. Here, we use three-dimensional modelling and computational fluid dynamics to establish the feeding mode of the enigmatic Ediacaran pentaradial eukaryote Arkarua. Through comparisons with two Cambrian echinoderms, Cambraster and Stromatocystites, we show that flow patterns around Arkarua strongly support its interpretation as a passive suspension feeder. Arkarua is added to the growing number of Ediacaran benthic suspension feeders, suggesting that the energy link between pelagic and benthic ecosystems was likely expanding in the White Sea assemblage (~ 558–550 Ma). The advent of widespread suspension feeding could therefore have played an important role in the subsequent waves of ecological innovation and escalation that culminated with the Cambrian explosion.

Subject terms: Palaeontology, Biomechanics

Introduction

The late Ediacaran (~ 571–541 Ma) was a pivotal interval in Earth’s history, which saw the initial radiation of large and complex multicellular eukaryotes (the so-called ‘Ediacaran macrobiota’), including some of the first animals1–3. Although Ediacaran ecosystems were, for many years, thought to have been fundamentally different from Cambrian ones4,5, there is growing evidence that they were more similar than previously thought, especially in terms of the construction and organization of communities, presence of key feeding strategies, and diversity of life modes6–9. One of the most important ecological innovations that emerged in the Ediacaran, and which is thought to have played a crucial role in structuring Phanerozoic communities, is macroscopic suspension feeding. Benthic suspension feeders are responsible for removing suspended organic particles from the water column, thereby reducing primary production and increasing the retention time for suspended particles on the seafloor. This provides a link between the pelagic and benthic realms and exerts a powerful control over rates and patterns of energy transport10–12. The evolution of benthic suspension feeding therefore marked a permanent step-increase in nutrient and energy fluxes to the sediment–water interface, and may have represented a primary ecological driver for the Cambrian explosion13.

Establishing when suspension feeding by macroscopic organisms became dominant in ecosystems is a key goal in evolutionary biology and geobiology. The appearance of the probable suspension feeders Cloudina and Namacalathus as major components of reefs in the latest Ediacaran ‘Nama’ assemblage (~ 550–541 Ma) indicates that suspension feeding had become an important and widespread ecological strategy shortly before the onset of the Cambrian12,14. Analysis of older Ediacaran communities (‘White Sea’ assemblage, ~ 558–550 Ma) suggests that competition for food within the water column became a significant factor at this time15, but the aberrant morphologies of many taxa from this assemblage, which lack analogues among modern species, makes determining their feeding modes problematic. Rahman et al.6 suggested that the triradial taxon Tribrachidium was a benthic suspension feeder, but White Sea-aged communities encompass a wide diversity of taxa which have yet to be analyzed in this context. It is therefore uncertain if suspension feeding played a prominent role in structuring benthic communities prior to 550 million years ago.

The White Sea assemblage, represented by fossils from the White Sea Region of Russia and the Flinders Ranges of South Australia, marks the apex of Ediacaran diversity16. Arkarua adami is one of the most enigmatic fossils from this assemblage, characterized by a small, disc-shaped body with five grooves radiating from a central depression on the upper surface. It is thought to have been sessile, resting on the seafloor in life17. Owing to its pentaradial body plan, Arkarua has been interpreted as the earliest known echinoderm17,18, but this phylogenetic position is debated19,20. Laflamme et al.21 suggested that most White Sea taxa, including Arkarua, were osmotrophs, feeding by absorbing dissolved organic carbon, as has been proposed for a wide range of Ediacaran organisms21,22. However, an alternative possibility, indicated by the general morphological similarity with the Cambrian edrioasteroid echinoderms Cambraster and Stromatocystites17, is that Arkarua was a suspension feeder, passively feeding on particles suspended in water, as inferred for edrioasteroids23,24. Here, we use a virtual modelling approach called computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to visualize water flow around putative feeding structures for models of Arkarua, and compare the resulting flow patterns to those produced by models of Cambraster and Stromatocystites. Using these data, we test the hypothesis that Arkarua was a benthic suspension feeder. The results allow us to build a more complete picture of White Sea assemblage palaeoecology, shedding light on the importance of suspension feeding in the Ediacaran.

Material and methods

Fossil specimens

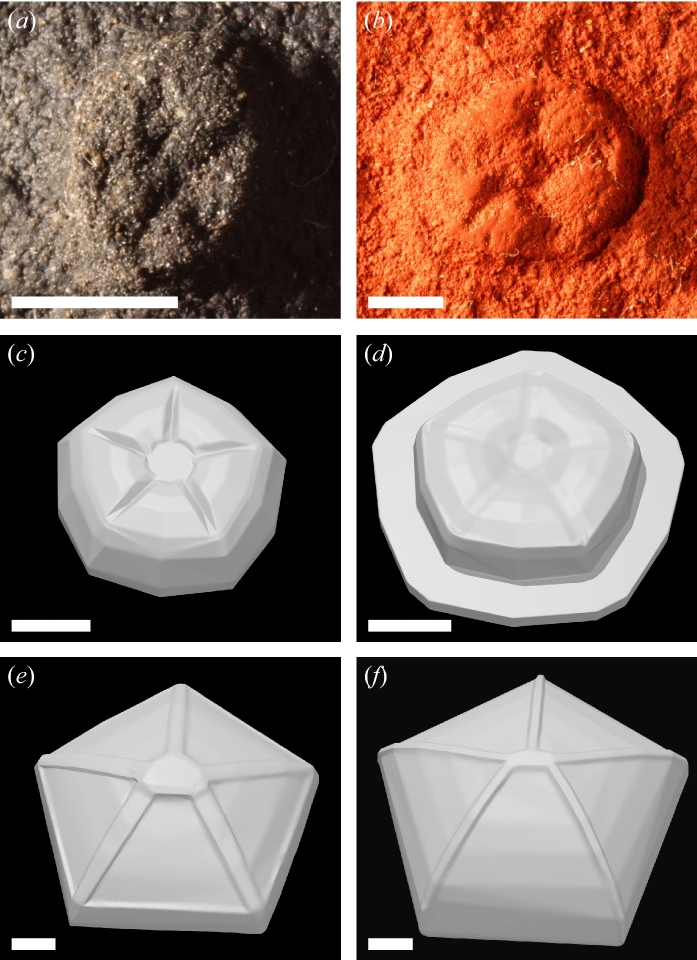

Arkarua adami comes from the Nilpena Member of the Rawnsley Quartzite (~ 555 Ma) in the Flinders Ranges, South Australia25. Fossils are preserved as external moulds in fine- to medium-grained sandstones, with some beds showing evidence of unidirectional current ripples and micro-scour. Deposition is thought to have occurred at storm wave base on an open marine shelf17,26,27. Two morphotypes have been described: (1) smaller (~ 4–5 mm in diameter) hemispherical forms (Fig. 1a) and (2) larger (~ 6–10 mm in diameter) discoidal forms with a marginal rim (Fig. 1b). Measurements of specimens in the collections of the South Australian Museum (SAM) are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

(a) Cast of Arkarua adami (SAMP P 40310) from Devil's Peak, Flinders Ranges, South Australia. (b) Cast of Arkarua adami (SAM P 26768) from the Chace Range, Flinders Ranges, South Australia. (c) Three-dimensional digital model of Arkarua morphotype 1. (d) Three-dimensional digital model of Arkarua morphotype 2. (e) Three-dimensional digital model of Cambraster. (f) Three-dimensional digital model of Stromatocystites. Scale bars = 2 mm.

Digital modelling

Three-dimensional digital models of the two Arkarua morphotypes (Fig. 1c,d) and the Cambrian edrioasteroids Cambraster cannati (Fig. 1e) and Stromatocystites pentangularis (Fig. 1f) were created using box modelling28 in Blender v. 2.79 (www.blender.org). Photographs of fossil specimens and published reconstructions17,29,30 were used as background images. In addition, virtual reconstructions of Arkarua specimens, generated with photogrammetry (Supplementary Information), were used as references to guide box modelling of the Arkarua morphotypes. For each model, a cube was created and then subdivided using loop cuts to increase the number of elements. Edges and vertices of the cube were translated, rotated and/or scaled to match the outlines of the reference images/reconstructions in different views. To represent more complex parts, additional elements were created by extruding faces of this object. Models were then scaled to life size, with model diameters (5.8 mm for Arkarua morphotype 1, 7.5 mm for Arkarua morphotype 2, 13 mm for Cambraster and 14 mm for Stromatocystites) obtained from measurements of fossil specimens, whereas model heights (1.65 mm for Arkarua morphotype 1, 1.8 mm for Arkarua morphotype 2, 3.6 mm for Cambraster and 9 mm for Stromatocystites) were estimated based on the relative dimensions of published reconstructions17,29,30. Models were exported from Blender and converted into non-uniform rational basis spline surfaces in Geomagic Studio 2012 (www.geomagic.com). To evaluate the feasibility of an osmotrophic feeding mode, we calculated surface area-to-volume (SA:V) ratios for each of the four models and compared them with extant and extinct osmotrophs. Digital models are available from Zenodo: 10.5281/zenodo.4497656.

Computational fluid dynamics

CFD simulations were carried out in COMSOL Multiphysics v. 5.4 (www.comsol.com) following established protocols6,9. A three-dimensional half cylinder, measuring 182 mm in length and 124 mm in diameter, was used as the computational domain (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Models were fixed to the lower boundary of this domain, which extended at least three times the length of the model upstream, ten times the length of the model downstream and five times the size of the model in all other directions. The physical properties of water (density = 1000 kg/m3, dynamic viscosity = 0.001 Pa·s) were assigned to the space surrounding the model, with a velocity inlet defined at the upstream end of the domain and a zero-pressure outlet at the downstream end. A no-slip boundary condition was assigned to the lower surface of the domain and the surfaces of the model, with a slip boundary condition assigned to the top and sides of the domain. The domain was meshed using free tetrahedral elements, with thin layers of prismatic elements inserted at the fluid–solid interface (Supplementary Fig. S1b,c). The shear-stress transport turbulence model was used to solve the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations, with a stationary solver used to compute the steady-state solution. A sensitivity analysis was carried out to determine the optimal mesh size for each model (Supplementary Information; Supplementary Tables S2–S5), which was then used in all subsequent simulations.

A total of four inlet velocities ranging from 0.05 to 0.20 m/s (Reynolds numbers of 285–2580; model diameter taken as the characteristic dimension) were simulated for each model, reflecting ambient current velocities in modern relatively deeper-water environments31,32 analogous to those inhabited by Arkarua. This velocity range is supported by sedimentological evidence including the grain size and the presence of bedforms such as current ripples and micro-scour17,26,27, which indicate flow velocities were regularly greater than 0.10 m/s33. The same inlet velocities were simulated for Cambraster and Stromatocystites, which are thought to have inhabited relatively high-energy and low-energy (respectively) offshore environments30.

Simulations were performed with models at three different orientations to the inlet (0°, 36° and 324°). In addition, simulations were repeated for both Arkarua morphotypes (with models orientated at 0° to the inlet) with model heights increased by 15% and 30% to account for possible diagenetic compaction of the sediment and ensuing compression of Arkarua specimens17, which might have caused us to underestimate the original relief of the living organisms. To test between osmotrophy and suspension feeding, we visualized CFD results as two-dimensional and three-dimensional plots showing flow patterns around the models. CFD results files are available from Zenodo: 10.5281/zenodo.4497656.

Results

SA:V ratios

Surface area-to-volume (SA:V) ratios calculated for the four digitally-modelled organisms (Fig. 1c–f) were within a narrow range of 0.61–2.48 mm–1. The two Arkarua models had slightly higher values (2.10 and 2.48 mm–1) than Cambraster and Stromatocystites (1.22 and 0.61 mm–1, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Surface area, volume and surface area-to-volume ratios for digital models of Arkarua, Cambraster and Stromatocystites.

| Model | Surface area (mm2) | Volume (mm3) | Surface area-to-volume ratio (mm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arkarua morphotype 1 | 65.89 | 31.45 | 2.10 |

| Arkarua morphotype 2 | 110.12 | 44.46 | 2.48 |

| Cambraster | 272.96 | 223.40 | 1.22 |

| Stromatocystites | 390.04 | 642.25 | 0.61 |

Computational fluid dynamics

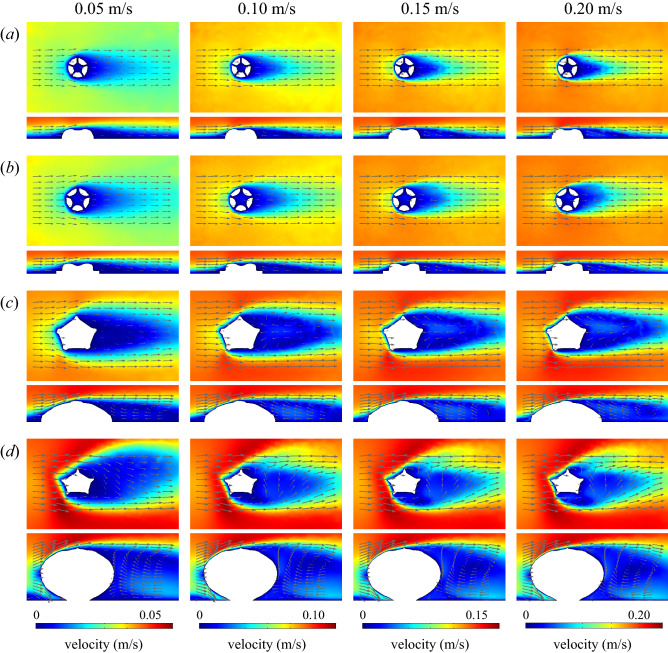

In all the CFD simulations, the velocity of fluid flow decreased as it approached the digital model and the lower boundary of the domain, with a velocity gradient (the boundary layer) developed in the immediate vicinity of these surfaces (Fig. 2; Supplementary Figs. S2, S4, S6, S8, S10, S12). The thickness of the boundary layer decreased as the inlet velocity increased, consistent with theoretical expectations. A region of recirculating flow (the wake) was seen downstream of the models (Fig. 2; Supplementary Figs. S2, S4, S6, S8, S10, S12). The size of the wake increased with the size of the model.

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional surface plots (horizontal and vertical cross-sections) of velocity magnitude with flow vectors (size of arrows proportional to natural logarithm of flow velocity magnitude) at four different inlet velocities (0.05–0.20 m/s). (a) Arkarua morphotype 1. (b) Arkarua morphotype 2. (c) Cambraster. (d) Stromatocystites. Direction of ambient flow from left to right.

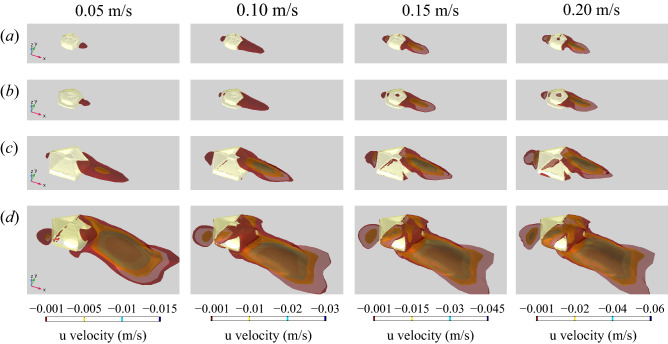

In the Arkarua models, an isolated pocket of low velocity flow was observed within the central depression and associated grooves at all modelled orientations and heights (Fig. 2a,b; Supplementary Figs. S2, S4, S10, S12). Additionally, in the original models of Arkarua morphotypes 1 and 2, localized areas of reversed flow, represented by negative values of velocity component u (parallel to the flow direction), occurred in the central depression when the inlet velocity was greater than or equal to 0.20 or 0.15 m/s, respectively (Fig. 3a,b; Supplementary Figs. S3, S5). For the Arkarua models with increased heights, reversed flow within the central depression also occurred at slightly lower velocities (0.15 m/s or greater for morphotype 1 and 0.10 m/s or greater for morphotype 2) (Supplementary Figs. S11, S13). In the edrioasteroid models, low velocity flow over the mouth and downstream ambulacra was seen regardless of orientation (Fig. 2c,d; Supplementary Figs. S6, S8), with areas of reversed flow adjacent to the downstream ambulacra at inlet velocities of 0.10 m/s or greater (Fig. 3c,d; Supplementary Figs. S7, S9).

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional isosurface plots of negative values of velocity component u (parallel to the x-axis) at three different inlet velocities (0.05–0.20 m/s). (a) Arkarua morphotype 1. (b) Arkarua morphotype 2. (c) Cambraster. (d) Stromatocystites. Direction of ambient flow from top left to bottom right.

Discussion

The calculated SA:V ratios (Table 1) argue against osmotrophy as the primary feeding mode for Arkarua. Osmotrophy relies on a high SA:V ratio to enhance the uptake of dissolved organic matter through osmosis22,34, but the values obtained for models of Arkarua (2.10 and 2.48 mm–1), Cambraster (1.22 mm–1) and Stromatocystites (0.61 mm–1) are much lower than extant osmotrophic megabacteria, which range from 8–20,000 mm–1 (see Laflamme et al.22). Ediacaran organisms interpreted as osmotrophs also had generally higher SA:V ratios than Arkarua; for example, theoretical models of the rangeomorph Fractofusus with fractally-branching modules have SA:V ratios of 2–10,000 mm–1 (see Laflamme et al.22). Moreover, Arkarua lacks any of the morphological adaptations for enhancing the SA:V ratio seen in rangeomorphs, such as constructional flattening or fractal branching21,22.

The results of our CFD simulations are also incompatible with an osmotrophic feeding mode for Arkarua, and instead strongly suggest that it was a suspension feeder. If Arkarua was an osmotroph, we would expect to see fluid flow evenly distributed across all surfaces of the models, maximizing the opportunities for uptake of dissolved organic carbon35. However, our results reveal that low velocity flow and, at higher inlet velocities, reversed flow was concentrated over specific parts of the models, i.e. the central depression and associated grooves (Figs. 2a,b, 3a,b; Supplementary Figs. S2–S5, S10–S13). Such flow patterns are more consistent with passive feeding on particles suspended in water using specialized feeding structures36, as suggested for some other Ediacaran organisms based on computer simulations of fluid flows6,9,37. Furthermore, our CFD simulations for the edrioasteroids Cambraster and Stromatocystites (which are widely regarded as passive suspension feeders23,24) reveal very similar flow patterns, with pockets of low velocity and reversed flow adjacent to the central mouth and downstream ambulacra (Figs. 2c,d, 3c,d; Supplementary Figs. S6–S9), further strengthening our inference of suspension feeding in Arkarua. While it is possible that osmotrophy could have served as a supplemental food source, as in some extant marine animals38–40, it would not have been an effective means of gathering nutrients in Arkarua.

Concentration of low velocity flow over the central depression and associated grooves in Arkarua indicates these structures were important for feeding, as previously suggested17. The observed flow patterns are most consistent with particle capture through gravitational deposition, with particles denser than water falling out of suspension over feeding structures under the influence of gravity41,42. This feeding strategy has been reported in a variety of modern sessile marine invertebrates, including bivalves, corals and crinoids43–46. Flow may have been channelled along the grooves towards the central depression, which presumably served as an opening into the body cavity where nutrients were absorbed.

Reconstruction of Arkarua as a benthic suspension feeder illustrates that the diversity and abundance of suspension feeding taxa in the White Sea assemblage was greater than previously thought. CFD analyses have shown that the White Sea taxon Tribrachidium was also a suspension feeder6, and hence the low-relief, hemispherical morphologies exhibited by both Arkarua and Tribrachidium probably evolved to enhance capture of suspended food particles just above the sediment–water interface. Moreover, the triradial body plans of other Ediacaran taxa, such as Albumares, Anfesta, Hallidaya, Rugoconites and Skinnera47, suggest that these too would have interacted with moving currents in a similar fashion, and thus likely also functioned as suspension feeders. White Sea ecosystems were therefore comprised of a substantial diversity and overall proportion of suspension-feeding organisms, which lived alongside phototrophs48, mobile mat grazers49, saprotrophs50, detritivores7 and osmotrophs21 in surprisingly complex benthic communities. This scenario invites two crucial questions with broad relevance for reconstructing ecological and evolutionary dynamics during the Neoproterozoic rise of animals. Firstly, why did so many (apparently unrelated) suspension feeders adopt a low-relief and hemispherical body plan? Secondly, what effects might the proliferation of suspension feeders have had on the structure and function of Ediacaran communities?

The morphology of extant sessile suspension feeders reflects, in part, a trade-off between feeding and stability. Adaptations that increase the height of an organism above the sediment–water interface allow it to take advantage of higher current velocities for feeding, but will also increase drag and, hence, the chances of dislodgement36,51. In this context, a low-relief, hemispherical body plan may represent one possible locally optimal morphology, minimizing drag and thus enhancing stability on the seafloor, while at the same time creating patterns of fluid flow that would have enabled passive suspension feeding6. A hemispherical aspect reduces drag and enables feeding in all orientations to current equally, and therefore might represent an adaptation to life in environments characterized by shifting current directions6,37. Hemispherical body plans have been adopted by sessile suspension feeders in a wide variety of metazoan phyla, including cnidarians, echinoderms, arthropods (e.g. barnacles) and chordates (e.g. Cnemidocarpa tunicates)36,51. Consequently, we suggest that the abundance of hemispherical body plans among Ediacaran macrobiota in the White Sea assemblage reflects both the expansion of benthic ecosystems from deep into shallow water environments characterized by strong and variable currents52 and the increasingly widespread availability of suspended food at low heights in the water column. With seafloor microbial mats being extensive at this time, turbulent flow near the sediment–water interface would have resulted in a large volume of re-suspended organic matter and bacteria. Moreover, recent biomarker work performed on White Sea-aged sediments suggests that algae was an important food source in shallow-water environments53, and thus could have been a valuable resource for benthic suspension-feeding communities.

The earliest benthic suspension feeders probably appeared in the ‘Avalon’ assemblage (~ 571–560 Ma). Although the vast majority of Avalon-aged taxa are generally regarded as osmotrophs21,22, the enigmatic triangular-shaped fossil Thectardis has been interpreted as a sponge on the basis of its aspect ratio54 (although see55), and could thus represent the earliest link between pelagic and benthic realms. Our results suggest this feeding behaviour had become more widespread by the White Sea assemblage, appearing in at least three putative clades of Ediacaran macrobiota (erniettomorphs, pentaradialomorphs and triradialomorphs6,9), in addition to possible sponges like Coronacollina and Paleophragmodictya56–58. As well as the expansion of suspension feeding strategies into new taxonomic groups, the White Sea assemblage was also characterized by increased ecological tiering, with an abundance of low-tiered suspension feeders just above the sediment–water interface. This trend extended into the latest Ediacaran Nama assemblage, with the expansion of likely suspension feeders into higher tiers (e.g. Corumbella59) and new ecological niches, such as reef crests (e.g. Cloudina and Namacalathus12,14). Consequently, our reconstruction of Arkarua as a benthic suspension feeder potentially highlights a late Ediacaran rise to prominence of suspension feeding in benthic ecosystems.

The organic matter captured by suspension feeders is typically either converted into biomass or excreted to the sediment, where it forms an invaluable energy source for organisms that rarely (or never) venture up higher into the water column60. The putative late Ediacaran increase in energy transport from the water column to the sediment surface would thus have represented a permanent step-increase in the bioavailable carbon at the sediment–water interface, and could have fuelled several of the dramatic ecological and evolutionary innovations seen during this interval, including the appearance of mobile benthic organisms, increased diversity of body plans, and exploitation of the sediment–water interface by bilaterian tracemakers (the ‘second wave’ of Ediacaran innovation proposed by Droser and Gehling61). In this light, the dramatic radiation in infaunal deposit-feeding behaviours evident in the succeeding Nama assemblage62–64 may have been an ecological response to a step-increase in benthic food availability. We acknowledge, however, that this model is speculative given that current understanding of Ediacaran feeding modes is incomplete. For example, if rangeomorphs are interpreted as suspension feeders65 rather than osmotrophs21,22, this would render Avalon-aged communities as almost entirely composed of suspension feeders. Moreover, the feeding modes of most White Sea taxa remain poorly understood; additional studies focussed on the palaeobiology of individual taxa are needed. Nevertheless, the growing number of probable suspension feeders from White Sea-aged communities raises the possibility that the link between pelagic and benthic realms strengthened during the late Ediacaran, resulting in increased energy flux to the sediment surface, and potentially supporting a diversification in benthic life habits. We note that this hypothesis is different from, but not mutually exclusive to, other resource-based models seeking to explain the dramatic increase in taxonomic and ecological diversity across the Avalon–White Sea transition15,66.

In summary, we show that the enigmatic Ediacaran pentaradial organism Arkarua adami was a passive suspension feeder, which took advantage of flow patterns created by its radially symmetrical and approximately hemispherical body plan. Arkarua thus joins a growing list of probable suspension feeders in the late Ediacaran White Sea assemblage, and suggests that a key pillar of the Phanerozoic marine carbon cycle – linkage between pelagic and benthic ecosystems – may have expanded from the Avalon to White Sea assemblages, ~ 571–550 Ma. In the absence of any obvious temporal correlation between putative environmental shifts (including the oxygenation state of global oceans) and the increases in both biological and ecological complexity in the late Ediacaran67, we propose that the expansion of benthic suspension feeding in the White Sea assemblage played an important role in shaping the waves of innovation that began in the late Ediacaran, and culminated with the Cambrian explosion2,3,68.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Mary-Anne Binnie for organising access to the Palaeontological Collections at the South Australian Museum. We are also grateful to Brandt Gibson for comments on an earlier version of the text.

Author contributions

I.A.R., D.C.G.-B., J.G.G and S.A.F.D. conceived the study. K.C. and M.J.A. created digital models. K.C. and I.A.R. carried out CFD simulations. K.C., I.A.R. and S.A.F.D. wrote the manuscript with scientific and editorial input from all other authors.

Funding

This work was funded by Australian Research Council Future Fellowship FT130101329 (D.C.G.-B.), National Science Foundation Grant 2007928 (S.A.F.D.) and Natural Environment Research Council Grant NE/V010859/1 (I.A.R.).

Data availability

Digital models in STL and IGES formats and CFD results files in MPH and DOCX formats are available from Zenodo: 10.5281/zenodo.4497656.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-83452-1.

References

- 1.Droser ML, Tarhan LG, Gehling JG. The rise of animals in a changing environment: global ecological innovation in the late Ediacaran. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2017;45:593–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-063016-015645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darroch SAF, Smith EF, Laflamme M, Erwin DH. Ediacaran extinction and Cambrian explosion. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018;33:653–663. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood R, et al. Integrated records of environmental change and evolution challenge the Cambrian explosion. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019;3:528–538. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0821-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMenamin MAS. The Garden of Ediacara: Discovering the First Complex Life. New York: Columbia University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seilacher A. Biomat-related lifestyles in the Precambrian. Palaios. 1999;14:86–93. doi: 10.2307/3515363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman IA, Darroch SAF, Racicot RA, Laflamme M. Suspension feeding in the enigmatic Ediacaran organism Tribrachidium demonstrates complexity of Neoproterozoic ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500800. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gehling JG, Droser ML. Ediacaran scavenging as a prelude to predation. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2018;2:213–222. doi: 10.1042/ETLS20170166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darroch SAF, Laflamme M, Wagner PJ. High ecological complexity in benthic Ediacaran communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018;2:1541–1547. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson BM, et al. Gregarious suspension feeding in a modular Ediacaran organism. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaaw0260. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonsdorff E, Blomqvist EM. Biotic couplings on shallow water soft bottoms–examples from the northern Baltic Sea. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 1993;31:153–176. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gili J-M, Coma R. Benthic suspension feeders: their paramount role in littoral marine food webs. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1998;13:316–321. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01365-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood R, Curtis A. Extensive metazoan reefs from the Ediacaran Nama Group, Namibia: the rise of benthic suspension feeding. Geobiology. 2014;13:112–122. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lerosey-Aubril R, Pates S. New suspension-feeding radiodont suggests evolution of microplanktivory in Cambrian macronekton. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3774. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06229-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penny AM, et al. Ediacaran metazoan reefs from the Nama Group, Namibia. Science. 2014;344:1504–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.1253393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell E, et al. The influence of environmental setting on the community ecology of Ediacaran organisms. Interface Focus. 2020;10:20190109. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2019.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bottjer DJ, Clapham ME. Evolutionary Paleoecology of Ediacaran Benthic Marine Animals. In: Xiao S, Kaufman AJ, editors. Neoproterozoic Geobiology and Paleobiology. Dordrecht: Springer; 2006. pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gehling JG. Earliest known echinoderm—a new Ediacaran fossil from the Pound Subgroup of South Australia. Alcheringa. 1987;11:337–345. doi: 10.1080/03115518708619143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mooi R, David B. Evolution within a bizarre phylum: homologies of the first echinoderms. Am. Zool. 1998;38:965–975. doi: 10.1093/icb/38.6.965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sprinkle J, Guensburg TE. Early radiation of echinoderms. Paleontol. Soc. Pap. 1997;3:205–224. doi: 10.1017/S1089332600000267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zamora S, Rahman IA. Deciphering the early evolution of echinoderms with Cambrian fossils. Palaeontology. 2014;57:1105–1119. doi: 10.1111/pala.12138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laflamme M, Darroch SAF, Tweedt SM, Peterson KJ, Erwin DH. The end of the Ediacara biota: extinction, biotic replacement, or Cheshire Cat? Gondwana Res. 2013;23:558–573. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2012.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laflamme M, Xiao S, Kowalewski M. Osmotrophy in modular Ediacaran organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14438–14443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904836106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith AB. Cambrian eleutherozoan echinoderms and the early diversification of edrioasteroids. Palaeontology. 1985;28:715–756. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith AB, Jell PA. Cambrian edrioasteroids from Australia and the origin of starfishes. Mem. Queensl. Mus. 1990;28:715–778. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gehling JG, García-Bellido DC, Droser ML, Tarhan LG, Runnegar B. The Ediacaran–Cambrian transition: sedimentary facies versus extinction. Estud. Geol. 2019;75:e099. doi: 10.3989/egeol.43601.554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarhan LG, Droser ML, Gehling JG, Dzaugis MP. Microbial mat sandwiches and other anactualistic sedimentary features of the Ediacara Member (Rawnsley Quartzite, South Australia): implications for interpretation of the Ediacaran sedimentary record. Palaios. 2017;32:181–194. doi: 10.2110/palo.2016.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid LM, Payne JL, García-Bellido DC, Jago JB. The Ediacara Member, South Australia: lithofacies and palaeoenvironments of the Ediacara biota. Gondwana Res. 2020;80:321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2019.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahman IA, Lautenschlager S. Applications of three-dimensional box modeling to paleontological functional analysis. Paleontol. Soc. Pap. 2017;22:119–132. doi: 10.1017/scs.2017.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, Sumrall CD, Parsley RL, Peng J. Kailidiscus, a new plesiomorphic edrioasteroid from the basal Middle Cambrian Kaili biota of Guizhou Province, China. J. Paleontol. 2010;84:668–680. doi: 10.1666/09-159.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zamora S, Sumrall CD, Vizcaïno D. Morphology and ontogeny of the Cambrian edrioasteroid echinoderm Cambraster cannati from western Gondwana. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 2013;58:545–559. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emelyanov EM. The Barrier Zones in the Ocean. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siedler G, Griffies SM, Gould J, Church JA, editors. Ocean Circulation and Climate: A 21st Century Perspective. Oxford: Academic Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stow DAV, et al. Bedform-velocity matrix: the estimation of bottom current velocity from bedform observations. Geology. 2009;37:327–330. doi: 10.1130/G25259A.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laflamme M, Narbonne GM. Ediacaran fronds. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2008;258:162–179. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer A, Plotnick R, Laflamme M. Experimental fluid mechanics of an Ediacaran frond. Palaeontol. Electron. 2012;15:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogel S. Life in Moving Fluids: The Physical Biology of Flow. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darroch SAF, Rahman IA, Gibson B, Racicot RA, Laflamme M. Inference of facultative mobility in the enigmatic Ediacaran organism Parvancorina. Biol. Lett. 2017;13:20170033. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2017.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorokin YI, Wyshkwarzev DI. Feeding on dissolved organic matter by some marine animals. Aquaculture. 1973;2:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(73)90141-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roditi HA, Fisher NS, Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA. Uptake of dissolved organic carbon and trace elements by zebra mussels. Nature. 2000;407:78–80. doi: 10.1038/35024069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Goeij JM, Moodley L, Houtekamer M, Carballeira NM, van Duyl FC. Tracing 13C-enriched dissolved and particulate organic carbon in the bacteria-containing coral reef sponge Halisarca caerulea: evidence for DOM feeding. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2008;53:1376–1386. doi: 10.4319/lo.2008.53.4.1376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubenstein DI, Koehl MAR. The mechanisms of filter feeding: some theoretical considerations. Am. Nat. 1977;111:981–994. doi: 10.1086/283227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LaBarbera M. Feeding currents and particle capture mechanisms in suspension feeding animals. Amer. Zool. 1984;24:71–84. doi: 10.1093/icb/24.1.71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernard FR. Particle sorting and labial palp function in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1795) Biol. Bull. 1974;146:1–10. doi: 10.2307/1540392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koehl MAR. Water Flow and the Morphology of Zoanthid Colonies. In: Taylor DL, editor. Proceedings of Third International Coral Reef Symposium. Miami: University of Miami; 1977. pp. 437–444. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyer DL. Length and spacing of the tube feet in crinoids (Echinodermata) and their role in suspension-feeding. Mar. Biol. 1979;51:361–369. doi: 10.1007/BF00389214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson AS, Sebens KP. Consequences of a flattened morphology: effects of flow on feeding rates of the scleractinian coral Meandrina meandrites. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1993;99:99–114. doi: 10.3354/meps099099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall CMS, Droser ML, Clites EC, Gehling JG. The short-lived but successful tri-radial body plan: a view from the Ediacaran of Australia. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2020;67:885–895. doi: 10.1080/08120099.2018.1472666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao S, et al. Affirming life aquatic for the Ediacara biota in China and Australia. Geology. 2013;41:1095–1098. doi: 10.1130/G34691.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gehling JG, Runnegar BN, Droser ML. Scratch traces of large Ediacara bilaterian animals. J. Paleontol. 2014;88:284–298. doi: 10.1666/13-054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evans SD, Gehling JG, Droser ML. Slime travelers: early evidence of animal mobility and feeding in an organic mat world. Geobiology. 2019;17:490–509. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koehl MAR. Effects of sea anemones on the flow forces they encounter. J. Exp. Biol. 1977;69:87–105. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boag TH, Stockey RG, Elder LE, Hull PM, Sperling EA. Oxygen, temperature and the deep-marine stenothermal cradle of Ediacaran evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2018;285:20181724. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bobrovskiy I, Hope JM, Golubkova E, Brocks JJ. Food sources for the Ediacara biota communities. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1261. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15063-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sperling EA, Peterson KJ, Laflamme M. Rangeomorphs, Thectardis (Porifera?) and dissolved organic carbon in the Ediacaran oceans. Geobiology. 2011;9:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2010.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Antcliffe JB, Callow RHT, Brasier MD. Giving the early fossil record of sponges a squeeze. Biol. Rev. 2014;89:972–1004. doi: 10.1111/brv.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gehling JG, Rigby JK. Long expected sponges from the Neoproterozoic Ediacara fauna of South Australia. J. Paleontol. 1996;70:185–195. doi: 10.1017/S0022336000023283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Erwin DH, et al. The Cambrian conundrum: early divergence and later ecological success in the early history of animals. Science. 2011;334:1091–1097. doi: 10.1126/science.1206375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clites EC, Droser ML, Gehling JG. The advent of hard-part structural support among the Ediacara biota: Ediacaran harbinger of a Cambrian mode of body construction. Geology. 2012;40:307–310. doi: 10.1130/G32828.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pacheco MLAF, et al. Insights into the skeletonization, lifestyle, and affinity of the unusual Ediacaran fossil Corumbella. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0114219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levinton J. Stability and trophic structure in deposit-feeding and suspension-feeding communities. Am. Nat. 1972;106:472–486. doi: 10.1086/282788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Droser ML, Gehling JG. The advent of animals: the view from the Ediacaran. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:4865–4870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403669112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mángano MG, Buatois LA. Decoupling of body-plan diversification and ecological structuring during the Ediacaran-Cambrian transition: evolutionary and geobiological feedbacks. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2014;281:20140038. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buatois LA, Almond J, Mángano MG, Jensen S, Germs GJB. Sediment disturbance by Ediacaran bulldozers and the roots of the Cambrian explosion. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:4514. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22859-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cribb AT, et al. Increase in metazoan ecosystem engineering prior to the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary in the Nama Group, Namibia. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019;6:190548. doi: 10.1098/rsos.190548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Butterfield, N. J. Constructional and functional anatomy of Ediacaran rangeomorphs. Geol. Mag. (in press).

- 66.Budd GE, Jensen S. The origin of the animals and a ‘Savannah’ hypothesis for early bilaterian evolution. Biol. Rev. 2017;92:446–473. doi: 10.1111/brv.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rooney AD, et al. Calibrating the coevolution of Ediacaran life and environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:16824–16830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002918117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muscente AD, Boag TH, Bykova N, Schiffbauer JD. Environmental disturbance, resource availability, and biologic turnover at the dawn of animal life. Earth Sci. Rev. 2018;177:248–264. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.11.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Digital models in STL and IGES formats and CFD results files in MPH and DOCX formats are available from Zenodo: 10.5281/zenodo.4497656.